| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | David Hernández Falagán | -- | 625 | 2025-08-13 10:26:14 | | | |

| 2 | Perry Fu | Meta information modification | 625 | 2025-08-13 10:58:43 | | |

Video Upload Options

In comparative analyses, specific features of the Spanish welfare and housing systems have often been emphasized. The case of Barcelona illustrates the extent to which these features are the result of a long-standing historical trajectory and the decisive impact of the challenges and policy responses adopted during Franco’s lengthy, dark, and gloomy regime. This period marked a significant shift, not only due to the persistent shortage of social rental housing, but also because of the early consolidation of a homeownership culture and its dominance in working-class suburban areas—a legacy that is completely different from that of the welfare states of Western Europe. Through a review of the literature and the analysis of primary sources, ongoing research on Barcelona seeks to clarify the factors and processes that led to this transformation, as well as its evolution during the democratic period, within an international context of economic liberalization and the dismantling of the welfare state.

References

- Bonomo, B. Politiche Abitative e Proprietà della Casa in Italia nel Secondo Dopoguerra; Sapienza University: Roma, Italy, 2019.

- Chambers, M.; Garriga, C.; Schlagenhauf, D.E. The Post-War Boom in Homeownership: An Exercise in Quantitative History. Editor. Express 2011, 62, 1–28.

- Collins, W.J.; Margo, R.A. Race and Home Ownership from the End of the Civil War to the Present. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 101, 355–359.

- Saunders, P. Restoring a Nation of Homeowners. What Went Wrong with Home Ownership in Britain, and How to Start Putting it Right; Civitas: Essex, UK, 2016.

- Woodin, T.; Crook, D.; Carpentier, V. Chapter heading Community and Mutual Ownership. A Historical Review; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2010.

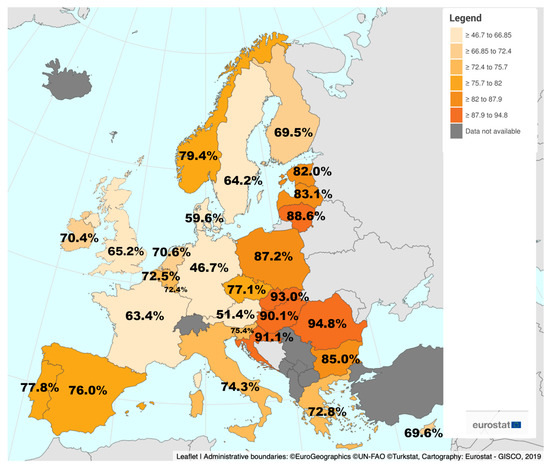

- Eurostat. Distribution of Population by Tenure Status, Type of Household and Income Group. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ILC_LVHO02__custom_5518940/default/map?lang=en (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990.

- Ferrera, M. The Southern Model of Welfare in Social Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 1996, 6, 17–37.

- Hoekstra, J.; Vakili, Z. High house prices and high vacancy rates: A Mediterranean paradox? In Proceedings of the ENHR 2007 International Conference “Sustainable Urban Areas”, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 25–28 June 2007.

- Angelini, V.; Laferrère, A.; Weber, G. Home-ownership in Europe: How did it happen? Adv. Life Course Res. 2013, 18, 83–90.

- Flora, P. Growth to Limits: The Western European Welfare States Since World War II; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1986; Volume 4.

- Sørvoll, J.; Nordvik, V. Social citizenship, inequality and homeownership. Postwar perspectives from the north of Europe. Soc. Policy Soc. 2020, 19, 293–306.

- Tsenkova, S. Housing change in East and Central Europe: Integration or fragmentation? Routledge: London, UK, 2017.

- Marcuse, P. Privatization and its discontents: Property rights in land and housing in the transition in Eastern Europe. In Cities After Socialism: Urban and Regional Change and Conflict in Post-Socialist Societies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 119–191.

- Huber, P.; Montag, J. Homeownership, Political Participation, and Social Capital in Post-Communist Countries and Western Europe. Kyklos 2020, 73, 96–119.

- Trilla, C. La Política D’habitatge en Una Perspectiva Comparada; La Caixa: Barcelona, Spain, 2001.

- Di Feliciantonio, C.; Aalbers, M.B. The Pre-histories of Neoliberal Housing Policies in Italy and Spain and their Reification in Times of Crisis. Hous. Policy Debate 2017, 28, 135–151.