| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Encyclopedia Editorial Office | -- | 1072 | 2025-04-29 03:32:13 | | | |

| 2 | Encyclopedia Editorial Office | + 11 word(s) | 1083 | 2025-04-29 03:36:25 | | |

Video Upload Options

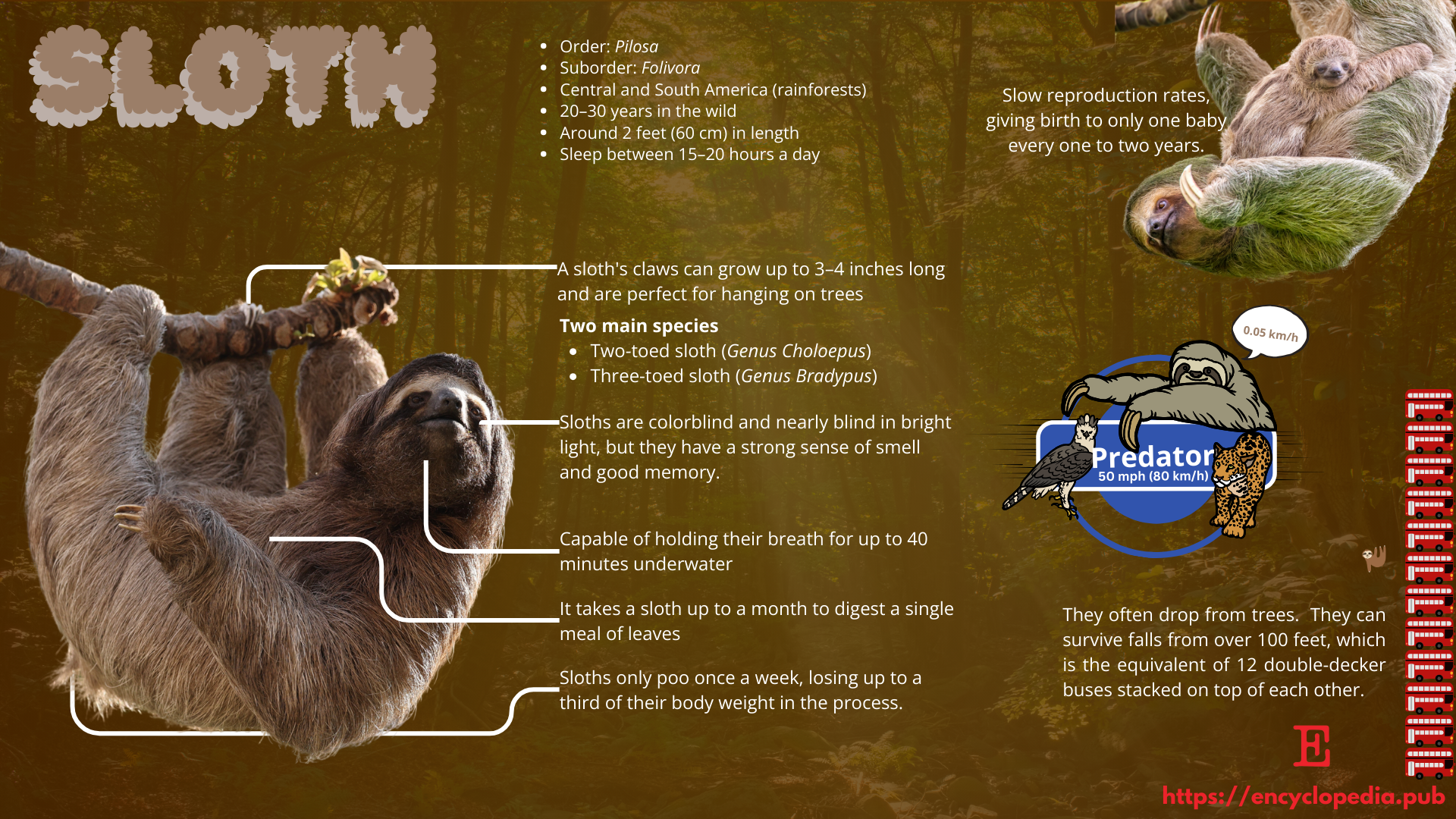

Sloths are some of the most fascinating and unique creatures in the animal kingdom. Known for their incredibly slow movements, these tree-dwelling mammals spend most of their lives hanging upside down in the rainforests of Central and South America. But there's so much more to them than just their leisurely pace.

1. Introduction

Sloths are some of the most distinctive and fascinating mammals found in the forests of Central and South America. Famous for their slow movement and seemingly perpetual smiles, sloths have evolved extraordinary adaptations for survival in the treetops. Although they are often depicted as lazy or sluggish, these traits are the result of millions of years of evolutionary fine-tuning. Today, sloths face new challenges as human activities alter the landscapes they call home. Understanding their biology, ecology, and evolutionary history reveals why sloths are not just cute curiosities but vital components of tropical ecosystems.

2. Evolution and Classification

Sloths belong to the order Pilosa and are most closely related to anteaters. They are divided into two families: the two-toed sloths (Choloepodidae) and the three-toed sloths (Bradypodidae). Although both groups share a similar lifestyle, they evolved these traits independently, an example of convergent evolution [1].

The ancestors of modern sloths were once much larger. Giant ground sloths, such as Megatherium and Eremotherium, roamed the Americas during the Pleistocene epoch. Some species, like Megatherium americanum, could weigh up to 4 tons and stood over 6 meters tall [2]. These ground-dwelling giants went extinct around 10,000 years ago, possibly due to a combination of climate change and human hunting.

Today, six species of sloths survive:

-

Three-toed sloths (Bradypus genus): Bradypus variegatus, Bradypus tridactylus, Bradypus torquatus, and the critically endangered Bradypus pygmaeus.

-

Two-toed sloths (Choloepus genus): Choloepus hoffmanni and Choloepus didactylus.

Despite sharing similar habits, two-toed and three-toed sloths are estimated to have diverged more than 30 million years ago [3].

Sloths infographic, created by Encyclopedia Editorial Team. (https://encyclopedia.pub/image/3507)

3. Anatomy and Physiology

Sloths possess a unique set of anatomical adaptations tailored for a life in the trees. Their long, curved claws (up to 10 cm) enable them to hang effortlessly from branches, often with their entire body weight suspended. Their limbs are disproportionately long compared to their body size, enhancing their reach among tree canopies.

Internally, sloths have an exceptionally slow metabolism, among the slowest of any mammal. Their heart rate averages around 30–50 beats per minute, and their body temperature can fluctuate widely, which is unusual for mammals (Gilmore et al., 2000). Their diet of tough, fibrous leaves is digested through a large, multi-chambered stomach that uses symbiotic bacteria to break down cellulose — a process that can take up to a month for a single meal to be fully processed.

Moreover, sloth fur is a micro-ecosystem of its own. It hosts green algae (Trichophilus welckeri), which helps camouflage the sloth against predators, as well as moths, beetles, and fungi [4]. Some studies suggest that the algae provide nutrients to the sloth when it grooms itself, representing a possible form of mutualism.

4. Behavior and Lifestyle

The quintessential trait of sloths — their slowness — is not a result of laziness but an energy-saving strategy. Sloths are adapted to survive on a low-energy diet of leaves that are low in calories and nutrients. By moving slowly, they reduce the need for food intake and lower their exposure to predators like harpy eagles and jaguars.

Sloths spend about 15–20 hours per day resting or sleeping. They are largely solitary animals, though territories can overlap, and some species occasionally tolerate the presence of others nearby.

Interestingly, despite their slow movements on land, sloths are surprisingly good swimmers. They can hold their breath underwater for up to 40 minutes by slowing their heart rate [5]. Swimming is often faster for a sloth than moving through the treetops, and they use rivers to travel between territories.

One of the most puzzling behaviors of sloths is their descent to the forest floor approximately once a week to defecate. This behavior is risky, as it exposes them to predators. Various hypotheses have been proposed to explain this behavior, including nutrient cycling for their fur micro-ecosystem and communication via scent marking [4].

5. Ecology and Role in the Ecosystem

Sloths play important ecological roles in their habitats. Their slow lifestyle and algae-coated fur contribute to nutrient cycles within the rainforest. By hosting diverse communities of moths, fungi, and algae, sloths indirectly support other species.

Their defecation may also fertilize trees by concentrating nutrients at the base of their home trees. Furthermore, sloths can be important seed dispersers, especially for plants whose fruits they consume.

The sloth’s predators — harpy eagles, jaguars, and ocelots — depend in part on the presence of sloths to sustain their populations. Thus, the loss of sloths could ripple through the entire rainforest ecosystem.

6. Threats and Conservation

Today, sloths face numerous threats, largely from human activities. The main threats include:

-

Deforestation: Loss of tropical forests due to agriculture, logging, and urban expansion destroys the sloths’ arboreal habitat, forcing them to ground level where they are vulnerable.

-

Roads and Traffic: As sloths attempt to cross roads between fragmented habitats, they are often struck by vehicles.

-

Pet Trade and Tourism: Sloths are increasingly captured for the illegal pet trade and are exploited as photo props for tourists, often leading to stress and early death.

Of particular concern is the pygmy three-toed sloth (Bradypus pygmaeus), found only on Isla Escudo de Veraguas off Panama. It is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN, with fewer than 100 individuals estimated to remain [6].

Conservation organizations are working to protect sloths through habitat preservation, wildlife corridors (to allow safe passage between forest fragments), and public education campaigns. Sanctuaries like the Sloth Conservation Foundation and Sloth Sanctuary of Costa Rica focus on rescue, rehabilitation, and research efforts.

Eco-tourism, when properly managed, also offers hope: by generating economic value from living sloths in the wild rather than as pets or photo props, local communities have incentives to protect sloth habitats.

7. Conclusion

Sloths are much more than the slow-moving icons of internet memes. They are survivors of an ancient lineage, master adapters to a challenging arboreal lifestyle, and vital components of their ecosystems. Their gentle lives are intricately linked with the forests they inhabit, and their survival depends on our ability to preserve those forests. Protecting sloths is not just about saving a charismatic species; it is about safeguarding the richness and interdependence of tropical life.

As research continues to reveal the complexity of sloth behavior, physiology, and ecology, one thing remains clear: these extraordinary animals deserve our admiration — and our protection.

References

- Presslee, S., Slater, G. J., Pujos, F., Forasiepi, A. M., Fischer, R., Molloy, K., ... & Collins, M. J. (2019). Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3(7), 1121–1130. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z

- Fariña, R. A., Vizcaíno, S. F., & Bargo, M. S. (1998). Body mass estimations in Lujanian (late Pleistocene–early Holocene of South America) mammal megafauna. Mastozoología Neotropical, 5(2), 87–108.

- Nyakatura, J. A. (2012). The convergent evolution of suspensory posture and locomotion in tree sloths. Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 19(3), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10914-012-9182-7

- Pauli, J. N., Mendoza, J. E., Steffan, S. A., Carey, C. C., Weimer, P. J., & Peery, M. Z. (2014). A syndrome of mutualism reinforces the lifestyle of a sloth. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1778), 20133006. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.3006

- McDonald, H. G. (2005). Paleoecology of extinct xenarthrans and the Great American Biotic Interchange. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History, 45(4), 313–333.

- Anderson, R. P., & Handley, C. O. (2001). A new species of three-toed sloth (Bradypus) from Panama. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 114(1), 1–33.