| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mehdi Imani | -- | 4916 | 2025-02-11 16:17:56 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | -2 word(s) | 4914 | 2025-02-13 02:26:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

This research paper presents a hybrid 2D Conv-RBM & LSTM model for efficient human action recognition. Achieving 97.3% accuracy with optimized frame selection, it surpasses traditional 2D RBM and 3D CNN techniques. Recognizing human actions through video analysis has gained significant attention in applications like surveillance, sports analytics, and human–computer interaction. While deep learning models such as 3D convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) deliver promising results, they often struggle with computational inefficiencies and inadequate spatial–temporal feature extraction, hindering scalability to larger datasets or high-resolution videos. To address these limitations, we propose a novel model combining a two-dimensional convolutional restricted Boltzmann machine (2D Conv-RBM) with a long short-term memory (LSTM) network. The 2D Conv-RBM efficiently extracts spatial features such as edges, textures, and motion patterns while preserving spatial relationships and reducing parameters via weight sharing. These features are subsequently processed by the LSTM to capture temporal dependencies across frames, enabling effective recognition of both short- and long-term action patterns. Additionally, a smart frame selection mechanism minimizes frame redundancy, significantly lowering computational costs without compromising accuracy. Evaluation on the KTH, UCF Sports, and HMDB51 datasets demonstrated superior performance, achieving accuracies of 97.3%, 94.8%, and 81.5%, respectively. Compared to traditional approaches like 2D RBM and 3D CNN, our method offers notable improvements in both accuracy and computational efficiency, presenting a scalable solution for real-time applications in surveillance, video security, and sports analytics.

1. Introduction

-

We introduce a novel hybrid 2D Conv-RBM + LSTM architecture that efficiently captures both spatial and temporal features for action recognition tasks. By leveraging the strengths of unsupervised spatial feature learning through Conv-RBM and temporal modeling through LSTM, the proposed method achieves robust and effective action recognition.

-

We incorporate a smart frame selection mechanism that reduces computational complexity by selecting only the most relevant frames in each video sequence. This innovation minimizes redundancy while preserving critical temporal information, enabling the network to focus on the most informative portions of the video.

-

We conduct extensive evaluations on three benchmark datasets: KTH [17], UCF Sports [18], and HMDB51 [19]. On the KTH and UCF Sports datasets, our method achieves state-of-the-art accuracy, surpassing all competing methods in the literature. On the HMDB51 dataset, while our method achieves competitive accuracy, certain other approaches demonstrate higher performance, particularly those leveraging transformer-based architectures or highly complex deep learning frameworks. Despite this, our method balances accuracy and computational efficiency, making it a promising solution for real-time action recognition tasks.

2. Related Work

2.1. CNN-Based Approaches for Spatial Feature Extraction

2.2. LSTM Networks for Temporal Dependencies

2.3. Restricted Boltzmann Machines (RBMs) and Conv-RBM Variants

2.4. Comparison Between Conv-RBM and CNN

2.5. Smart Frame Selection in Video Analysis

2.6. Benchmark Datasets and Evaluation

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Preprocessing and Frame Selection

3.2. Two-Dimensional Convolutional Restricted Boltzmann Machine (2D Conv-RBM)

where Z is the partition function, summing over all possible configurations of V and H:

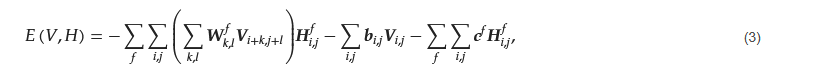

The energy function E(V, H), shown in Equation (3), is expressed as

where 𝑾𝑓𝑘,𝑙 represents the convolutional filter connecting the visible and hidden layers, bi,j is the bias for visible units, and cf is the bias for the hidden feature maps. The activation of hidden units is governed by the conditional probability of a hidden unit 𝑯𝑓𝑖,𝑗 being active (set to 1) given the visible layer V, as shown in Equation (4):

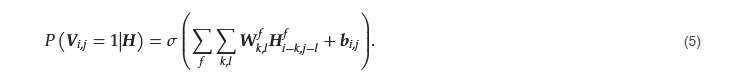

where 𝜎(𝑥)=1/1+𝑒−𝑥 is the sigmoid activation function. Similarly, the visible layer can be reconstructed from the hidden units using the conditional probability in Equation (5):

The feature map Fi,j extracted at location (i, j) is computed as Equation (6):

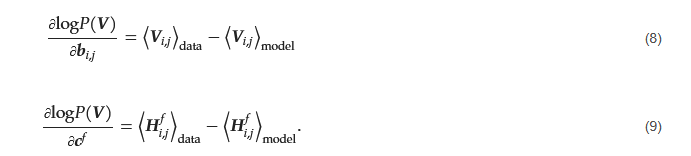

where ⟨⋅⟩data and ⟨⋅⟩model represent expectations under the data distribution and the model distribution, respectively. Similarly, the updates for visible and hidden biases are computed using Equations (8) and (9):

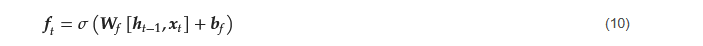

3.3. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) for Temporal Modeling

and the candidate cell state 𝑪̃𝑡, which represents new information to be added, is calculated as

The cell state Ct is then updated by combining the retained information from the previous cell state (modulated by the forget gate) with the newly computed candidate cell state (modulated by the input gate):

The output gate determines the information to be propagated to the hidden state ht, which is used for the next time step or for making predictions. The output gate is calculated as

and the hidden state is then updated using the current cell state and the output gate:

3.4. Feature Classification Using Fully Connected Network

where y represents the predicted probability distribution over all action classes. The network is trained to minimize the cross-entropy loss, which measures the difference between the predicted probability distribution and the true labels. The cross-entropy loss function is given by

3.5. Proposed Architecture Specifications

| Parameter | Value/Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| K (smart frame selection) | 32 frames | based on [38] |

| Frame dimensions | 64 × 64 (grayscale, black-and-white) | Common practice in video action recognition models |

| Visible layer size (Conv-RBM) |

64 × 64 (corresponding to the frame dimensions) | Based on RBM architecture for spatial extraction |

| Hidden layer size (Conv-RBM) |

64 × 32 × 32 (after pooling) | Reduced spatial dimensions with 64 feature maps |

| Convolutional filter size (Conv-RBM) |

3 × 3 (with stride 1) | Standard in CNNs, balances spatial locality and depth |

| Pooling layer (Conv-RBM) | 2 × 2 (max pooling) | Reduces feature map dimensions by half |

| LSTM units | 256 units | Suitable for temporal modeling of moderate complexity |

| Number of LSTM layers | 2 layers | Allows capturing both short- and long-term dependencies |

| Optimizer | Adam optimizer (learning rate: 0.001) | Adaptive learning rate method for efficient convergence |

| Loss function | Cross-entropy loss | Commonly used in classification tasks |

| Regularization (dropout) | Dropout rate: 0.4 (LSTM layer and FC layer) | Prevents overfitting by dropping 40% of neurons |

| Learning rate | 0.001 | Default for Adam, tuned for stability |

| Batch size | 32 | Balances between computational load and convergence |

| Epochs | 100 | Enough for deep architectures like Conv-RBM + LSTM |

References

- Mihanpour, A.; Rashti, M.J.; Alavi, S.E. Human Action Recognition in Video Using DB-LSTM and ResNet. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Wireless Research (ICWR), Tehran, Iran, 22 April 2020.

- Ma, M.; Marturi, N.; Li, Y.; Leonardis, A.; Stolkin, R. Region-Sequence Based Six-Stream CNN Features for General and Fine-Grained Human Action Recognition in Videos. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 76, 545–558.

- Dai, C.; Liu, X.; Zhong, L.; Yu, T. Video-Based Action Recognition Using Spatial and Temporal Features. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Cybermatics Congress, Halifax, NS, Canada, 30 July 2018.

- Johnson, D.R.; Uthariaraj, V.R. A Novel Parameter Initialization Technique Using RBM-NN for Human Action Recognition. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2020, 1, 30.

- Cob-Parro, A.C.; Losada-Gutiérrez, C.; Marrón Romera, M.; Gardel Vicente, A.; Muñoz, I.B. A New Framework for Deep Learning Video-Based Human Action Recognition on the Edge. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 238, 122220.

- Silva, D.; Manzo-Martinez, A.; Gaxiola, F.; Gonzales-Gurrola, L.C.; Alonso, G.R. Analysis of CNN Architectures for Human Action Recognition in Video. Comput. Sist. 2022, 26, 67–80.

- Manakitsa, N.; Maraslidis, G.S.; Moysis, L.; Fragulis, G.F. A Review of Machine Learning and Deep Learning for Object Detection, Semantic Segmentation, and Human Action Recognition in Machine and Robotic Vision. Technologies 2024, 12, 15.

- Soentanto, P.N.; Hendryli, J.; Herwindiati, D. Object and Human Action Recognition from Video Using Deep Learning Models. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Signal and Image Processing Systems (ICSIGSYS), Bandung, Indonesia, 16 July 2019; pp. 88–93.

- Begampure, S.; Jadhav, P.M. Intelligent Video Analytics for Human Action Detection: A Deep Learning Approach with Transfer Learning. Int. J. Comput. Dig. Syst. 2022, 11, 57–72.

- Li, C.; Huang, Q.; Li, X.; Wu, Q. Human Action Recognition Based on Multi-Scale Feature Maps from Depth Video Sequences. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 32111–32130.

- Liu, X.; Yang, X. Multi-Stream with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Human Action Recognition in Videos. In Neural Information Processing, Proceedings of the 25th International Conference, ICONIP 2018, Siem Reap, Cambodia, 13 December 2018; Proceedings, Part I 25; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 251–262.

- Ulhaq, A.; Akhtar, N.; Pogrebna, G.; Mian, A. Vision Transformers for Action Recognition: A Survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.05700.

- Arnab, A.; Dehghani, M.; Heigold, G.; Sun, C.; Lučić, M.; Schmid, C. ViViT: A Video Vision Transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11 October 2021; pp. 6836–6846.

- Bertasius, G.; Wang, H.; Torresani, L. Is Space-Time Attention All You Need for Video Understanding? In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Virtual, 18 July 2021; Volume 2, p. 4.

- Khan, S.; Naseer, M.; Hayat, M.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, F.S.; Shah, M. Transformers in Vision: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–41.

- Khan, S.; Naseer, M.; Hayat, M.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, F.S.; Shah, M. Transformers in Vision: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–41.

- Schüldt, C.; Laptev, I.; Caputo, B. Recognizing Human Actions: A Local SVM Approach. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Cambridge, UK, 23 August 2004; pp. 32–36.

- Rodriguez, M.D.; Ahmed, J.; Shah, M. Action mach a spatio-temporal maximum average correlation height filter for action recognition. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Anchorage, AK, USA, 23 June 2008.

- Kuehne, H.; Jhuang, H.; Garrote, E.; Poggio, T.; Serre, T. HMDB: A Large Video Database for Human Motion Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Barcelona, Spain, 6 November 2011.

- Raza, A.; Al Nasar, M.R.; Hanandeh, E.S.; Zitar, R.A.; Nasereddin, A.Y.; Abualigah, L. A Novel Methodology for Human Kinematics Motion Detection Based on Smartphones Sensor Data Using Artificial Intelligence. Technologies 2023, 11, 55.

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Two-Stream Convolutional Networks for Action Recognition in Videos. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); Curran Associates, Inc.: Newry, UK, 2014; Volume 27, pp. 568–576.

- Zhu, J.; Zou, W.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, L.; Huang, G. Action Machine: Toward Person-Centric Action Recognition in Videos. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2019, 11, 1633–1637.

- Carreira, J.; Zisserman, A. Quo Vadis, Action Recognition? A New Model and the Kinetics Dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21 July 2017.

- Kulkarni, S.S.; Jadhav, S. Insight on Human Activity Recognition Using the Deep Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging Smart Computing and Informatics (ESCI), Pune, India, 1 March 2023.

- Yang, C.; Mei, F.; Zang, T.; Tu, J.; Jiang, N.; Liu, L. Human Action Recognition Using Key-Frame Attention-Based LSTM Networks. Electronics 2023, 12, 2622.

- Abdelbaky, A.; Aly, S. Two-Stream Spatiotemporal Feature Fusion for Human Action Recognition. Vis. Comput. 2021, 37, 1821–1835.

- Liu, T.; Ma, Y.; Yang, W.; Ji, W.; Wang, R.; Jiang, P. Spatial-Temporal Interaction Learning Based Two-Stream Network for Action Recognition. Inf. Sci. 2022, 606, 864–876.

- Donahue, J.; Anne Hendricks, L.; Guadarrama, S.; Rohrbach, M.; Venugopalan, S.; Saenko, K.; Darrell, T. Long-Term Recurrent Convolutional Networks for Visual Recognition and Description. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7 June 2015; pp. 2625–2634.

- Zheng, T.; Liu, C.; Liu, B.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Qin, X.; Guo, Y. Scene Recognition Model in Underground Mines Based on CNN-LSTM and Spatial-Temporal Attention Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Symposium on Computer, Consumer, and Control (IS3C), Taichung City, Taiwan, 13 November 2020; pp. 513–516.

- Saoudi, E.M.; Jaafari, J.; Andaloussi, S.J. Advancing Human Action Recognition: A Hybrid Approach Using Attention-Based LSTM and 3D CNN. Sci. Afr. 2023, 21, e01796.

- Liu, D.; Yan, Y.; Shyu, M.; Zhao, G.; Chen, M. Spatio-Temporal Analysis for Human Action Detection and Recognition in Uncontrolled Environments. Int. J. Multimed. Data Eng. Manag. (IJMDEM) 2015, 1, 1–18.

- Su, Y. Implementation and Rehabilitation Application of Sports Medical Deep Learning Model Driven by Big Data. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 156338–156348.

- Hossen, M.A.; Naim, A.G.; Abbas, P.E. Deep Learning for Skeleton-Based Human Activity Segmentation: An Autoencoder Approach. Technologies 2024, 12, 96.

- Lee, H.; Grosse, R.; Ranganath, R.; Ng, A.Y. Convolutional Deep Belief Networks for Scalable Unsupervised Learning of Hierarchical Representations. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14 June 2009; pp. 609–616.

- Osadchy, M.; Miller, M.; Cun, Y. Synergistic Face Detection and Pose Estimation with Energy-Based Models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 17; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005.

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444.

- Salakhutdinov, R.; Hinton, G. Deep Boltzmann Machines. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS), Clearwater Beach, FL, USA, 16 April 2009; pp. 448–455.

- Gowda, S.N.; Rohrbach, M.; Sevilla-Lara, L. Smart Frame Selection for Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 2 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 1451–1459.

- Zhang, X.; Liu, T.; Lo, K.; Feng, J. Dynamic Selection and Effective Compression of Key Frames for Video Abstraction. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2003, 24, 1523–1532.

- Hasebe, S.; Nagumo, M.; Muramatsu, S.; Kikuchi, H. Video Key Frame Selection by Clustering Wavelet Coefficients. In Proceedings of the 12th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Vienna, Austria, 6 September 2004.

- Xu, Q.; Wang, P.; Long, B.; Sbert, M.; Feixas, M.; Scopigno, R. Selection and 3D Visualization of Video Key Frames. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (ICSMC), Istanbul, Turkey, 10 October 2010.

- Kulbacki, M.; Segen, J.; Chaczko, Z.; Rozenblit, J.; Klempous, R.; Wojciechowski, K. Intelligent Video Analytics for Human Action Recognition: The State of Knowledge. Sensors 2023, 9, 4258.

- Feichtenhofer, C.; Pinz, A.; Wildes, R.P.; Zisserman, A. Deep Insights into Convolutional Networks for Video Recognition. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2020, 128, 420–437.

- Tsai, J.K.; Hsu, C.; Wang, W.Y.; Huang, S.K. Deep Learning-Based Real-Time Multiple-Person Action Recognition System. Sensors 2020, 17, 4857.

- Fischer, A.; Igel, C. An Introduction to Restricted Boltzmann Machines. In Progress in Pattern Recognition, Image Analysis, Computer Vision, and Applications, Proceedings of the 17th Iberoamerican Congress, CIARP, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 3–6 September 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 14–36.

- Srivastava, N.; Salakhutdinov, R. Multimodal Learning with Deep Boltzmann Machines. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 15, 2949–2980.