Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chan Ho Park | -- | 4062 | 2024-04-17 04:08:30 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | -3 word(s) | 4059 | 2024-04-18 10:01:25 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Le, T.H.; Kim, M.P.; Park, C.H.; Tran, Q.N. Physical Hydrogen Storage Materials. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/56589 (accessed on 08 March 2026).

Le TH, Kim MP, Park CH, Tran QN. Physical Hydrogen Storage Materials. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/56589. Accessed March 08, 2026.

Le, Thi Hoa, Minsoo P. Kim, Chan Ho Park, Quang Nhat Tran. "Physical Hydrogen Storage Materials" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/56589 (accessed March 08, 2026).

Le, T.H., Kim, M.P., Park, C.H., & Tran, Q.N. (2024, April 17). Physical Hydrogen Storage Materials. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/56589

Le, Thi Hoa, et al. "Physical Hydrogen Storage Materials." Encyclopedia. Web. 17 April, 2024.

Copy Citation

Hydrogen is a future energy carrier in the global energy system and has the potential to produce zero carbon emissions. For the non-fossil energy sources, hydrogen and electricity are considered the dominant energy carriers for providing end-user services, because they can satisfy most of the consumer requirements. Hence, the development of both hydrogen production and storage is necessary to meet the standards of a “hydrogen economy”. The physical and chemical absorption of hydrogen in solid storage materials is a promising hydrogen storage method because of the high storage and transportation performance.

hydrogen

physical hydrogen storage

hollow spheres

carbon-based materials

1. Compressed Hydrogen Storage Materials

Hydrogen compression is the most widely used technology to store and utilize hydrogen gas as an energy source, with several outstanding advantages [1][2]. First, the compression technique is well developed, with hydrogen filling and release occurring at high rates. Moreover, hydrogen release does not require energy [2][3]. Among the various storage materials, hollow spheres are most widely used for compressed hydrogen storage. Hollow spheres not only provide high surface area but also encapsulate hydrogen within pores. Moreover, the high surface area and porosity allow hybridization with other materials via binding sites on the surface or in the pores [4]. Hence, the absorption and catalytic activities of the hollow spheres can be increased significantly. In addition, the good mechanical strength and low specific weight of hollow spheres make them good hydrogen containers [5]. Controlling the different conditions, such as reaction time, pH, temperature, and ratio of reactants, can simplify the fabrication of hollow spheres of uniform sizes. In hollow nanospheres, hydrogen can be absorbed in both atomic and molecular forms [6].

Hollow spheres with average sizes ranging from micrometers to nanometers have attracted considerable research attention. Various types of hollow spheres of different sizes and from different materials, including carbon, glass, metal, and nonmetal, have been developed.

1.1. Hollow Carbon Spheres (HCSs)

HCSs are mainly fabricated by two methods: hard templating and soft templating, which use different template types to create a hollow sphere (HS). The hard-templating approach employs special hard particles as a “core template” to build a hollow structure. The core is removed after a carbon shell is formed on the surface of the core. Silica, polymers, and hard metal particles are often used as core templates in hard-templating procedures. In soft templating, a hollow structure is directly generated by the self-assembly of carbon and other organic compounds. Hence, the core templates are “soft” precursor molecules, which easily decompose during the final pyrolysis.

HCSs are excellent materials for hydrogen storage. Their mesoporous structure provides a high Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) value, voids, and hollow spaces, which can be occupied by hydrogen; thus, a high hydrogen capacity can be achieved. However, the HCS structure has a significant influence on the hydrogen storage capacity. The shape and size of the HCS play important roles in hydrogen diffusion in the substrate. When the adsorption energy is higher than the release energy, hydrogen can easily occupy the active sites that strongly depend on the morphologies of the material. In addition, the deposition of hydrogen into the pores of the HCS can be facilitated by the defects and thin walls of the HCS; hence, the spaces between the layers can be freed, increasing the amount of hydrogen stored in the HCS [7][8][9]. Hydrogen storage based on HCS has been reported in several studies, as partly presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Various types of HCS used for hydrogen storage.

| Materials | Temperature (°C) | Pressure (bar) |

H2 Storage Capacity (wt%) | Ave. Particle Size (nm) | Ave. Pore Size (nm) | Total Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Surface Area (m2/g) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pd-hollow carbon spheres | 40 | 24 | 0.36 | ~250 | n/a | 0.2514–0.9754 | 147–617 | [10] |

| 2 | Necklace-like hollow carbon nanospheres (CNS) | 0.89 | 60 | 5 | n/a | 594.32 | [7] | ||

| 3 | Ni-decorated hollow carbon spheres | 25 | 90 | 1.23 | 5100 | n/a | 0.31 | 28.6 | [11] |

| 4 | Hollow nitrogen-containing carbon spheres (N-HCS) | −196 | 80 | 1.03 | ~250 | 1.38–20 | 0.84 | 872 | [12] |

| 25 | 80 | 2.21 | |||||||

| 5 | Fe-nanoparticle–loaded hollow carbon spheres | 300 | 20 | 5.6 | 200–500 | ~90 | n/a | 160 | [13] |

| 6 | Metallic Mg ions diffused in hollow carbon nanospheres (HCNS) | 270 | 6.78 | 440–9800 | 28 | n/a | 1810 | [14] | |

| 370 | 7.85 | ||||||||

| 7 | Zeolite-like hollow carbon | −196 | 1 | 2.6 | ~5000 | 0.6–0.8 | ~2.41 | 3200 | [15] |

Wu et al. successfully synthesized necklace-like hollow carbon nanospheres (CNSs) with narrow pore distributions using pentagon-containing reactants. The results of their electrochemical hydrogen storage experiments showed that CNSs afforded a capacity of 242 mAh/g at a current density of 200 mA/g, corresponding to a hydrogen storage of 0.89 wt%, which is considerably greater than the electrochemical capacities of solid chain carbon spheres and multiwalled carbon nanotubes [7]. This confirms that the structure and morphology of carbon materials strongly affect the electrochemical hydrogen storage.

Doping hollow carbon materials with metals for hydrogen storage is known as hydrogen spillover [16]. Metals doped onto carbon materials can increase the binding energy between hydrogen and the pore walls. In addition, binding can occur between the hydrogen molecules and doped metallic atoms [17]. Thus, metal doping can enhance the hydrogen storage of materials. Among the various metal-doped hollow carbons used for enhancing hydrogen storage, palladium (Pd)-doped carbon materials have been reported to improve the hydrogen storage performance [18][19][20]. Hydrogen molecules easily dissociate on the Pd surface, which limits the storage efficiency. Hence, to decrease the active surface area of Pd to achieve good catalytic performance and improve the hydrogen storage capacity, small particles of Pd are doped onto the porous surface of the material.

In addition to metal and nonmetal doping, the hydrogen storage capacity can be enhanced by improving the surface area of the HCS. Yang et al. used chemical vapor deposition to successfully synthesize zeolite-like HC materials with large surface areas. This material demonstrated the effect of surface area on hydrogen storage capacity, which was 2.6 wt% at a pressure of 1 bar and reached 8.33 wt% at a pressure of 20 bar. This capacity of the zeolite HC material was recorded as the highest value ever reported among HC materials.

1.2. Hollow Glass Microspheres (HGMs)

HGMs, also known as microballoons or microbubbles, are mainly composed of borosilicate and soda lime silica. The sizes of HGMs range from 100 nm to 5 µm with a wall thickness ranging from 1.5 to 3 µm and pore size from 100 to 500 nm [21][22]. The wall thickness of HGMs strongly determines their crush strength; the higher the sphere density, the higher the crush strength. Owing to their excellent chemical stability, chemical resistance, strong mechanics, low density, high-temperature operation, high water resistance, noncombustibility, nonexplosibility, nontoxicity, and particularly, low-cost production, HGMs are considered as high-potential hydrogen transporting and storing materials [9][10][23].

HGMs must be operated under high pressure and high temperature to enhance the hydrogen diffusion into the HGMs. This is because not only the sizes of the gas molecules but also the temperature can change the gas diffusivity. After hydrogen molecules are absorbed in the HGMs, the temperature must be decreased to room temperature to reduce the diffusivity rate and retain the loaded hydrogen molecules in the pore cavities. For the hydrogen-release process, it is necessary to heat the HGMs to high temperatures. The optimal temperature for both hydrogen absorption and desorption is over 300 °C [24][25].

HGMs can be fabricated using dry-gel or liquid-droplet approaches. The high-temperature furnace in which the initial particles are formed plays an important role in both methods. First, the blowing agent is broken down to release the gas within the dried gel or liquid. The fast growth of gaseous products leads to the appearance of bubbles and the formation of hollow droplets. Thereafter, the hollow droplets rapidly cool from the liquid state to form HGMs [26]. Regarding the synthesis of HGMs, Wang et al. presented a basic formula for a new type of HGM, based on the traditional fabrication approaches, experiences in this material industry, and interrelated businesses. According to their proposal, HGM comprised quartz sand, K2CO3, Na2B8O13.4H2O, Na2CO3, Ca(OH)2, NaAlO2, Li2CO3, and H2O in weight percentages of 27, 14.5, 15, 10, 3.5, 3, 0.5, and 26.5%, respectively. Hence, the main chemical components of HGM were SiO2 (68–75%), Na2O (5–15%), CaO (8–15%), B2O3 (15–20%), and Al2O3 (2–3%) [27].

Dalai et al. presented a type of HGM for hydrogen storage, which was synthesized using an air–acetylene flame spheroidization method using urea as the blowing agent. With a microsphere diameter of 10–200 μm and wall thickness of 0.5–2 μm, they showed hydrogen storage capacity at ambient temperature and at 200 °C under a pressure of 10 bar. The results indicated that the adsorption capacity at ambient temperature was lower than that at 200 °C [28]. This confirmed that the higher the temperature, the better the gas diffusivity. At high temperatures, hydrogen molecules could pass through the HGM walls toward the hollow pores and were retained in them.

The poor thermal conductivity of HGMs restricts hydrogen molecule loading during the absorption and desorption processes, resulting in a poor hydrogen storage capacity [25]. It has been discovered that when HGMs are doped with photoactive agents such as Ti, Cr, V, Fe, Zn, Mg, and Co, the gas diffusion rate is strongly enhanced by light illumination compared with that of traditional heating furnace approaches [25][29][30][31].

Dalai et al. synthesized HGM samples loaded with Fe and Mg to improve their heat transfer properties, thereby enhancing their hydrogen storage capacity. For Fe doping, the feed glass powder was mixed with certain amounts of ferrous chloride tetrahydrate solution and magnesium nitrate hexahydrate salt solution to obtain 0.2–2 wt% Fe loading and 0.2–3.0 wt% Mg loading, respectively, in the HGMs. Hydrogen adsorption experiments on all HGMs doped with Fe and Mg were performed at 10 bar and 200 °C for 5 h. The results indicated that the hydrogen uptake capacity of Fe-doped HGMs was approximately 0.56 wt% at 0.5 wt% iron loading. Increasing the iron content did not enhance the hydrogen absorption because of spheroidization and the FeO/Fe block, which prevented the accessibility of some pores. This was confirmed by the results of 0.21 wt% uptake capacity with 2 wt% Fe doping in HGMs. Meanwhile, the Mg-doped sample exhibited a hydrogen adsorption increase from 1.23 to 2.0 wt% as the Mg loading percentage increased from 0 to 2.0 wt%. This is similar to the phenomenon of Fe doping; if the amount of Mg in the HGMs was over 2 wt%, nanocrystals of MgO/Mg that could close the pores appeared, thereby decreasing hydrogen storage capacity [32].

To sum up, the metal doping can increase the porosity of HGMs and then lead to an enhancement in hydrogen storage capacity. However, the too high concentrations of metal can result in the formations of metal oxide layers or the agglomeration metal particles, which can close the pores of HGMs and then decrease the hydrogen loading volume. Hence, doped-metal concentration optimization is extremely crucial to obtain the highest hydrogen storage capacity for HGMs. Overall, the researchers summarize the general characterization of the glass microspheres in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of characterization of glass microspheres (GMs).

| Preparation Method | Types | Advantages | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Co-loaded HGMs have also been fabricated [33][34]. The results revealed that the number of pores in the HGMs increased significantly and that the hydrogen storage capacity reached a maximum of approximately 2 wt% at Co concentration ≤2 wt%. When the amount of Co exceeded 2 wt%, energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis confirmed the formation of cobalt oxides on the walls of HGMs, which occupied the pores and prevented hydrogen diffusion.

2. Physical Absorption Materials

The physical hydrogen absorption process involves loading hydrogen onto the material surface. The origin of this process is the resonant fluctuations in the charge distribution, which are known as dispersive forces or van der Waals interactions. The interaction forces between hydrogen molecules and other materials are quite weak; therefore, physisorption only occurs at temperatures lower than 0 °C [35]. However, because of its advantages of high energy efficiency [21], high rates of loading and unloading [21][36], and good refueling time [37], physisorption has been widely used in the recent years. Hence, absorbent materials have been developed and improved to meet the physisorption requirements. A good hydrogen absorbent depends on two factors: (1) the binding energy between hydrogen molecules and materials, which directly affects the operating temperature of the hydrogen storage system, and (2) the availability of a high average surface area per unit volume [38]. Recently, materials considered excellent candidates for hydrogen physisorption include carbon-based materials such as activated carbon (AC), carbon nanotubes (CNT), graphite nanofibers (GNF), graphene, zeolites, and MOFs, which are further discussed in the following sections.

2.1. Carbon-Based Materials

Carbon is one of the most abundant elements in both living and nonliving organisms. Carbon materials are easily prepared as powders with high porosity and have a propensity to interact with gas molecules. Therefore, carbon is a well-known medium capable of absorbing gases and has been used as a detoxifier and purifier.

Carbon-based materials have attracted much attention as promising materials for hydrogen storage because of their several advantages such as high surface area, high porosity with diverse pore structures, good chemical stability, low weight, and low cost [39][40]. Various carbon-based materials are used for hydrogen storage. The researchers focus on the use of materials such as AC, CNT, GNF, and graphene for hydrogen storage, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Carbon-based materials used in hydrogen storage.

| Material | Definition | Advantages | wt% H2 | T (K) | P (bar) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activated carbon (AC) | Modified synthetic carbon consisting of high-surface-area amorphous carbon and graphite; fabricated through thermal or chemical procedures [41] | High specific surface area Mechanical and chemical stabilities Microporous structure Relatively low cost Feasible commercial scaling [42][43] |

0.1 | 298 | 10 | [44] |

| 2.02 | 77 | |||||

| 0.6 | 298 | 120 | [45] | |||

| 4 | 77 | |||||

| 0.85 | 77 | 100 | [46] | |||

| 1.2 | 298 | 200 | [47] | |||

| 2.7 | 500 | |||||

| 5.6 | 77 | 40 | ||||

| 1.09–2.05 | 298 | 0.00011 | [48] | |||

| 5 | 77 | 30–60 | [49] | |||

| Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) | CNTs are macromolecules containing a hexagonal arrangement of hybridized carbon atoms, which may be formed by rolling up a single sheet of graphene to form single-walled nanotubes (SWNTs) or multiple sheets of graphene to form multiwalled nanotubes (MWNTs) [50] | Unique structure Narrow size distribution and pore volume High surface area High strength Good electrical conductivity Good mechanical and thermal properties Low density Chemical stability Special functional properties [51][52][53][54] |

SWNT | |||

| 0.8 | 30 | [55] | ||||

| 1.73 | 77 | 100 | [56] | |||

| 4.77 | 323 | [57] | ||||

| 4.77 | 323 | [58] | ||||

| MWNT | ||||||

| 0.2 | 298 | 100 | [59] | |||

| 0.54 | 77 | 10 | [60] | |||

| 1.7 | 298 | 120 | [61] | |||

| 2 | 0.05 | [62] | ||||

| 3.46 | 127.9 | [63] | ||||

| 3.8 | 425 | 30 | [64] | |||

| Graphite nanofibers (GNFs) | GNFs are produced from the dissociation of carbon-containing gases over a catalyst surface (e.g., metal or alloy) through chemical deposition. The solid consists of very small graphite platelets of width 30–500 Å, stacked in a perfectly arranged conformation [65] | Herringbone structure High degree of defects (exhibits the best performance for hydrogen storage) Several pretreatment procedures: oxidative, reductive, and inert environments [66] |

1 | 300 | 20 | [67] |

| 1.2 | 77 | 20 | [68] | |||

| 3.3 | 298 | 48.3 | [69] | |||

| 4–6.5 | 298 | 121.6 | [70] | |||

| 1.3–7.5 | 298 | 100 | [71] | |||

| 10–15 | 300 | [72] | ||||

| 7–10 (irreversible) | [73] | |||||

| 20–30 (reversible) |

||||||

| Graphene-based materials | Graphene is a monolayer while graphite is a multilayer of carbon atoms strongly bound in a hexagonal crystal lattice. This is a carbon allotrope in the sp2 hybridized form with a molecular bond length of 0.142 nm [74] | High specific surface area High mechanical strength High corrosive-environment resistance High thermal and electrical conductivities [75][76] Various oxygen-containing functional groups |

0.055 | 293 | 1.06 | [77] |

| 0.13 | ||||||

| 0.14 | 298 | 1 | [78] | |||

| 1.18 | 60 | |||||

| 2.2 | 298 | 100 | [79] | |||

| 3.3 | 323 | [80] | ||||

| 4.3 | 298 | 40 | [81] | |||

| 1 | 293 | 120 | ||||

| 5 | 77 | |||||

| 6.28 | 298 | 1.01 | [82] | |||

| 10.5 | 77 | 10 | [83] | |||

2.2. Zeolites

Zeolites are three-dimensional, microporous, and highly crystalline aluminosilicate materials. Zeolites have a tetrahedral framework structure in which Si and Al atoms are tetrahedrally coordinated through shared oxygen atoms. Zeolites are well-known materials with channels and cages in which cations, water, and small molecules can reside. In addition, their high thermal stabilities and good ion-exchange capacities render them a huge potential promising media for hydrogen storage [84][85].

Zeolites can be classified as natural or synthetic. Natural zeolites exhibit improved resistivity and thermal stability in different environments [86]. However, they contain impurities that are not uniform in crystal size; therefore, they cannot be utilized in industrial applications [87].

Zeolites can be fabricated using various raw materials. To meet the requirements of economic efficiency, the raw materials should be readily available, relatively pure, selective, and inexpensive. Raw materials such as kaolin, rice husk ash, paper sludge, fly ash, blast furnace slag, lithium slag, and municipal solid waste are mostly used for zeolite fabrication.

Zeolites can be synthesized though different approaches including solvothermal, hydrothermal, ionothermal, alkali fusion and leaching, microwave, and ultrasound energy methods, which have been presented in previous studies [87]. Among these approaches, the hydrothermal process is the most widely used, particularly for the synthesis of zeolite membranes [88].

Owing to their excellent properties and various synthetic processes, zeolites are considered as good hydrogen storage candidates. Dong et al. investigated the hydrogen storage capacities of different zeolites including Na-LEV, H-OFF, Na-MAZ, and Li-ABW. The results showed that at a pressure of 1.6 MPa and temperature of 77 K, the capacities of Na-LEV, H-OFF, Na-MAZ, and Li-ABW were 2.07, 1.75, 1.64, and 1.02 wt%, respectively [85]. This result confirms that micropores with a higher volume and diameter, approximating the kinetic diameters of the hydrogen molecules, play a vital role in enhancing the zeolite capacity.

Recently, Sun et al. developed Monte Carlo simulations to predict hydrogen loading under different pressure and temperature conditions for MOFs, hypercrosslinked polymers, and zeolites. Regarding the pressure value, meta-learning allowed the identification of the optimal temperature with the highest working capacity for hydrogen storage.

2.3. MOFs

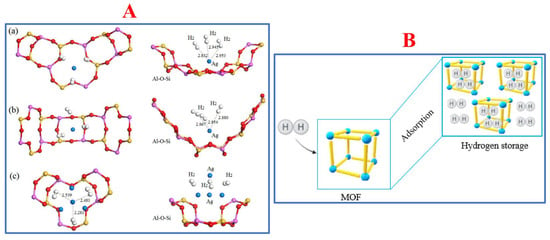

MOFs are an extensive class of crystalline materials that contain metal ions, metal clusters, and organic linkers. Organic linkers such as azoles (1,2,3-triazole, pyrrodiazole, etc.), dicarboxylates (glutaric acid, oxalic acid, succinic acid, malonic acid, etc.), and tricarboxylates (citric acid, trimesic acid, etc.) are commonly used in MOF fabrication [89][90]. In addition to controlling the metal/ligand ratio, changing the reaction temperature and modifying the organic linker are strategies to afford MOFs with good pore structures and high-dimensional frameworks [91], which significantly affect the hydrogen storage capacity. The main hydrogen storage mechanism of MOFs is similar to that of other porous materials such as hollow spheres, carbon-based materials, or zeolites: hydrogen molecules occupy and are kept in their vacants (the pores). The schematic mechanism examples of zeolites and MOFs are described in Figure 1.

Figure 1. (A) Hydrogen adsorption of zeolites materials named (a) aAg0.29Li0.71-LSX, (b) bAg0.43Li0.57-LSX, and (c) cAg0.29Li0.71-LSX. Reprinted with permission from [92]. Copyright 2019, MDPI; (B) Scheme of MOFs capturing hydrogen via their adsorbent properties. Reprinted with permission from [93]. Copyright 2022, MDPI.

MOFs materials are excellent candidates for potential applications in clean energy such as media for storing gases such as hydrogen and methane because of their high crystallinity, large internal surface area that can reach up to 6000 m2/g, and ultrahigh porosity with up to 90% free volume [94]. In addition, the variability in the metal and organic components in their structures endows MOFs with good designability, tunable structures, and properties. However, the production of MOFs is quite complex, and the hydrogen uptake efficiency of MOFs at ambient temperature is low. Therefore, improvements in the MOF fabrication technology are necessary [95].

A wide range of MOFs synthesis processes have been developed, which are summarized in Table 4. After synthesis, the MOF material obtained is typically available in a powder form. The incorporation of powders into relevant devices is quite difficult; this can prevent the utilization of MOFs in energy or gas-storage applications [96]. For example, if the MOFs are introduced as a loose powder into a tank with pipe fittings, they may be easily blown off into the surroundings, causing difficulties in handling and contamination in pipe fittings. In addition, their low packing density can compromise the volumetric capacities of the pipe fittings. Scientists have made great efforts to shape MOFs using the techniques presented in Table 4. The choice of the shaping technique depends on the fabrication approach and expected textural properties of the MOF materials [97][98]. Shaped MOF materials with appropriate mechanical strength, low flow resistance, and intact or high secondary surface areas and pore volumes are desired for better hydrogen storage performance [96].

Table 4. Various synthesis and powder-shaping methods for metal–organic framework (MOF) materials.

| MOF Synthesis Methods | MOF Powder-Shaping Methods |

|---|---|

| 1. Microwave assisted method | 1. Uniaxial pressing |

| 2. Sonochemitry | 2. Coating |

| 3. Electrochemistry | 3. Foaming |

| 4. Mechanochemistry | 4. Templating |

| 5. Hydrothermal approach | 5. Casting |

| 6. Solvothermal approach | 6. Granulation |

| 7. Extrusion | |

| 8. Pulsed current processing |

Hydrogen molecules have low polarizability. In addition, interactions between hydrogen and most MOFs are relatively weak. Previous research showed that the isosteric heat of hydrogen absorbed in the highly porous MOFs was approximately −5 kJ/mol because of the weak interactions of hydrogen molecules [95]. Hence, cryogenic temperatures are essential for obtaining reasonable hydrogen capacities in MOFs. Many research groups synthesized and investigated their MOF materials for hydrogen storage, such as MIL-53 (Cr) modified with Pd-loaded activated carbon (MIL-53 Cr) [99], MIL-101 (Cr) with zeolite-templated carbon ZTC (MIL-101 (Cr)/ZTC) [100], iron-based MOF (Fe-BTT) [101], and Co-based MOF (Co-MOF) [102]. They obtained hydrogen storage capacities of less than 5 wt%. With the improvements in the components and structures of materials, as well as using suitable pressures, the recent MOF materials including Zr-based MOFs (NU-1101, NU-1102, NU-1103), Al-based MOFs (NU-1501-Al) [103], and robust azolate-based MOFs (MFU-4/Li) [104] achieved remarkable increases of 9.1, 9.6, 12.6, 14, and 9.4 wt%, respectively, in hydrogen storage capacities.

However, storage at ambient temperatures remains a challenge. To overcome the limitations of the driving ranges in fuel-cell vehicles when using adsorption-based hydrogen storage technology, researchers have been developing different methods to increase the performance of MOF materials at higher temperatures. For example, open metal sites in the framework can act as strong adsorption sites for hydrogen loading at ambient temperatures. Lim et al. synthesized Be-based MOF (Be-BTB) with open metal sites. The Be-BTB material with a high BET surface area of 4400 m2/g presented a hydrogen adsorption capacity of 2.3 wt% at 298 K and 100 bar, which is much higher than that of the previous studies [105]. In addition, doping with metal ions or incorporating carbon-based materials may introduce a hydrogen spillover effect (HSPE) that can improve the hydrogen storage capacity of materials at room temperature. The HSPE is a surface phenomenon in which active hydrogen atoms generated by the dissociation of hydrogen molecules on metal surface migrate to the support surface and take part in the catalytic reaction of substance adsorbed on that site [106][107]. There are two conditions ensuring the HSPE can occur. First, there is the existence of metals capable of adsorbing dissociated hydrogen to convert hydrogen molecules into hydrogen atoms or hydrogen ions. Second, there is the presence of an acceptor for active hydrogen species and a channel and driver for the transfer of reactive hydrogen species [108]. The discovery of the HSPE has opened a new strategy in designing efficient catalysts. Especially, the HSPE has attracted much attention as one of the most potential technologies for enhancing the hydrogen storage performance of porous materials including MOFs at ambient temperature. The capacity of materials with induced hydrogen spillover was approximately five times higher than that of pristine MOFs [109]. Yang and co-workers doped 10 wt% Pt/AC catalysts into isoreticular MOF (IRMOF) materials to form a bridging spillover structure between carbon bridges and hydrogen spillovers, leading to a significant enhancement in the hydrogen storage performance. At 298 K and 100 bar, the hydrogen storage capacities of IRMOF-1 and IRMOF-8 increased from 0.4 to 3 wt% and from 0.5 to 4 wt%, respectively [110][111]. Table 5 summarizes the hydrogen storage capacities of some MOF materials.

Table 5. Summary of hydrogen storage capacities of various MOF materials.

| MOF Materials Used for Hydrogen Storage at Low Temperature | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Temperature (K) | Pressure (bar) | H2 Storage Capacity (wt%) | Reference |

| Co-MOF | 77 | 1 | 1.62 | [102] |

| MIL-53 | 77 | 60 | 1.92 | [99] |

| MIL-101 (Cr)/ZTC | 77 | 1 | 2.55 | [100] |

| CAU-1 | 70 | 1 | 4 | |

| UBMOF-31 | 77 | 60 | 4.9 | [101] |

| Fe-BTT | 77 | Low Pressure | 2.3 | [112] |

| 87 | 1.6 | |||

| 77 | 95 | 4.1 | ||

| NOTT-400 | 77 | 1 | 2.14 | [113] |

| 20 | 3.84 | |||

| NOTT-401 | 77 | 1 | 2.31 | |

| 20 | 4.44 | |||

| NU-1101 | 77–160 | 100–5 | 9.1 | [114] |

| NU-1102 | 77–160 | 100–5 | 9.6 | |

| NU-1103 | 77–160 | 100–5 | 12.6 | |

| NPF-200 | 77 | 100–5 | 8.7 | [115] |

| NU-1500 | 77–160 | 100–5 | 8.2 | [116] |

| NU-1501-Al | 77–160 | 100–5 | 14 | [103] |

| MFU-4/Li | 77–160 | 100–5 | 9.4 | [104] |

| MOF materials used for hydrogen storage at ambient temperature | ||||

| Material | Temperature (K) | Pressure (bar) | H2 storage capacity (wt%) | Reference |

| HKUST-1 | 298 | 65 | 0.35 | [117] |

| Cu-BTC | 303 | 35 | 0.47 | [118] |

| HKUST-1 | 303 | 35 | 0.47 | [119] |

| CB/Pt/MOF-5 | 298 | 100 | 0.62 | [120] |

| Zn2 (dobpdc)MOFs | 298 | 100 | 1.3 | [121] |

| Mg2 (dobpdc)MOFs | 298 | 100 | 1.8 | |

| Pd-CNMS/MOF-5 | 298 | 100 | 1.8 | [122] |

| 75 | 1.6 | |||

| 50 | 1.4 | |||

| Be-BTB | 298 | 100 | 2.3 | [105] |

| V2Cl2.8 | 298 | 100 | 1.64 | [123] |

| NU-150I-Al | 296 | 100 | 2.9 | |

| IRMOF-1 | 298 | 100 | 3 | [110] |

| IRMOF-8 | 298 | 100 | 4 | [90] |

3. Advantages and Disadvantages of Physical Hydrogen Storage Materials

Hydrogen storage technologies play an extremely important role in the “hydrogen economy”. It is necessary to continuously improve and develop storage materials for the hydrogen industry. As mentioned in the Introduction section, compared to chemical storage materials, the outstanding properties (Table 6) of the physical absorbents and the fact that they do not release greenhouse gases facilitate the global energy transition proceeding effectively as well as achieving the global “net zero emission” target sooner. However, each physical material has both its strengths and weaknesses. The limitations of these materials (hollow spheres[124][125], carbon-based materials[126][127][128], zeolites[129][130], MOFs[131][132]) presented in Table 6 are still challenges in practical hydrogen storage applications.

Table 6. Advantages and disadvantages of physical hydrogen storage materials.

| Property | Prospects | Consequences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material | |||

| Hollow spheres |

|

|

|

| Carbon-based materials |

|

|

|

| Zeolites |

|

|

|

| MOFs |

|

|

|

References

- Bipin Kumar Gupta, O.N. Srivastava. Further studies on microstructural characterization and hydrogenation behaviour of graphiticnanofibres. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy . 2001, 26, 857-862.

- Yury S. Nechaev, Evgeny A. Denisov, Alisa O. Cheretaeva,Nadezhda A. Shurygina, Ekaterina K. Kostikova,Andreas Öchsner, and Sergei Yu. Davydov. On the Problem of “Super” Storage of Hydrogen in Graphite Nanofibers. C. 2022, 8(2), 23.

- Jensen, J.O.; Vestbø, A.P.; Li, Q.; Bjerrum, N.J. The Energy Efficiency of Onboard Hydrogen Storage. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 446–447, 723–728.

- Gröger, H.; Kind, C.; Leidinger, P.; Roming, M.; Feldmann, C. Nanoscale Hollow Spheres: Microemulsion-Based Synthesis, Structural Characterization and Container-Type Functionality. Materials 2010, 3, 4355–4386.

- Lou, X.W.; Archer, L.A.; Yang, Z. Hollow Micro-/Nanostructures: Synthesis and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 3987–4019.

- Gupta, A.; Shervani, S.; Amaladasse, F.; Sivakumar, S.; Balani, K.; Subramaniam, A. Enhanced Reversible Hydrogen Storage in Nickel Nano Hollow Spheres. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 22032–22038.

- Wu, C.; Zhu, X.; Ye, L.; OuYang, C.; Hu, S.; Lei, L.; Xie, Y. Necklace-like Hollow Carbon Nanospheres from the Pentagon-Including Reactants: Synthesis and Electrochemical Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 8543–8550.

- Fang, B.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.H.; Yu, J.-S. Controllable Synthesis of Hierarchical Nanostructured Hollow Core/Mesopore Shell Carbon for Electrochemical Hydrogen Storage. Langmuir 2008, 24, 12068–12072.

- Jurewicz, K.; Frackowiak, E.; Béguin, F. Towards the Mechanism of Electrochemical Hydrogen Storage in Nanostructured Carbon Materials. Appl. Phys. A 2004, 78, 981–987.

- Michalkiewicz, B.; Tang, T.; Kalenczuk, R.; Chen, X.; Mijowska, E. In Situ Deposition of Pd Nanoparticles with Controllable Diameters in Hollow Carbon Spheres for Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2013, 38, 16179–16184.

- Kim, J.; Han, K.-S. Ni Nanoparticles-Hollow Carbon Spheres Hybrids for Their Enhanced Room Temperature Hydrogen Storage Performance. Trans. Korean Hydrog. New Energy Soc. 2013, 24, 550–557.

- Jiang, J.; Gao, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Xia, K.; Hu, J. Enhanced Room Temperature Hydrogen Storage Capacity of Hollow Nitrogen-Containing Carbon Spheres. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 210–216.

- Soni, P.K.; Bhatnagar, A.; Shaz, M.A. Enhanced Hydrogen Properties of MgH2 by Fe Nanoparticles Loaded Hollow Carbon Spheres. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2023, 48, 17970–17982.

- Elsabawy, K.M.; Fallatah, A.M. Over Saturated Metallic-Mg-Ions Diffused Hollow Carbon Nano-Spheres/Pt for Ultrahigh-Performance Hydrogen Storage. Mater. Lett. 2018, 221, 139–142.

- Yang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Mokaya, R. Enhanced Hydrogen Storage Capacity of High Surface Area Zeolite-like Carbon Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 1673–1679.

- Chung, T.-Y.; Tsao, C.-S.; Tseng, H.-P.; Chen, C.-H.; Yu, M.-S. Effects of Oxygen Functional Groups on the Enhancement of the Hydrogen Spillover of Pd-Doped Activated Carbon. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 441, 98–105.

- Ramos-Castillo, C.M.; Reveles, J.U.; Zope, R.R.; de Coss, R. Palladium Clusters Supported on Graphene Monovacancies for Hydrogen Storage. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 8402–8409.

- Zielinska, B.; Michalkiewicz, B.; Chen, X.; Mijowska, E.; Kalenczuk, R.J. Pd Supported Ordered Mesoporous Hollow Carbon Spheres (OMHCS) for Hydrogen Storage. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2016, 647, 14–19.

- Rangel, E.; Sansores, E. Theoretical Study of Hydrogen Adsorption on Nitrogen Doped Graphene Decorated with Palladium Clusters. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 6558–6566.

- Adams, B.D.; Ostrom, C.K.; Chen, S.; Chen, A. High-Performance Pd-Based Hydrogen Spillover Catalysts for Hydrogen Storage. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 19875–19882.

- Lim, K.L.; Kazemian, H.; Yaakob, Z.; Wan Daud, W. Solid-State Materials and Methods for Hydrogen Storage: A Critical Review. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2010, 33, 213–226.

- Shetty, S.; Hall, M. Facile Production of Optically Active Hollow Glass Microspheres for Photo-Induced Outgassing of Stored Hydrogen. Fuel Energy Abstr. 2011, 36, 9694–9701.

- Dresselhaus, M.S.; Thomas, I.L. Alternative Energy Technologies. Nature 2001, 414, 332–337.

- Snyder, M.; Wachtel, P.; Hall, M.; Shelbyy, J. Photo-Induced Hydrogen Diffusion in Cobalt-Doped Hollow Glass Microspheres. Phys. Chem. Glas.-Eur. J. Glas. Sci. Technol. Part B 2009, 50, 113–118.

- Rapp, D.B.; Shelby, J.E. Photo-Induced Hydrogen Outgassing of Glass. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 2004, 349, 254–259.

- Ouyang, L.; Chen, K.; Jiang, J.; Yang, X.S.; Zhu, M. Hydrogen Storage in Light-Metal Based Systems: A Review. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 829, 154597.

- Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, T.; Li, W. Research on the Preparation and Performances of a New Type of Hollow Glass Microspheres. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 821, 12010.

- Dalai, S.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Shrivastava, P.; Sivam, S.P.; Sharma, P. Preparation and Characterization of Hollow Glass Microspheres (HGMs) for Hydrogen Storage Using Urea as a Blowing Agent. Microelectron. Eng. 2014, 126, 65–70.

- Li, F.; Zhou, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, Z. Permeation and Photo-Induced Outgassing of Deuterium in Hollow Glass Microspheres Doped with Titanium. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 49, 303–313.

- Li, F.; Li, J.; Feng, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B. Influence of Titanium Doping on the Structure and Properties of Hollow Glass Microspheres for Inertial Confinement Fusion. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 2016, 436, 22–28.

- Yu, Y.; Kimura, K. Preparation of V or W Doped TiO2 Coating Hollow Glass Spheres and Photocatalytic Characterization. J.-Min. Mater. Process. Inst. Jpn. 2002, 118, 206–210.

- Dalai, S.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Sharma, P.; Choo, K.Y. Magnesium and Iron Loaded Hollow Glass Microspheres (HGMs) for Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 16451–16458.

- Dalai, S.; Savithri, V.; Sharma, P. Investigating the Effect of Cobalt Loading on Thermal Conductivity and Hydrogen Storage Capacity of Hollow Glass Microspheres (HGMs). Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 11608–11616.

- Dalai, S.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Shrivastava, P.; Sivam, S.; Sharma, P. Effect of Co Loading on the Hydrogen Storage Characteristics of Hollow Glass Microspheres (HGMs). Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 3304–3312.

- Züttel, A. Materials for Hydrogen Storage. Mater. Today 2003, 6, 24–33.

- Møller, K.T.; Jensen, T.R.; Akiba, E.; Li, H. Hydrogen—A Sustainable Energy Carrier. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2017, 27, 34–40.

- Rivard, E.; Trudeau, M.; Zaghib, K. Hydrogen Storage for Mobility: A Review. Materials 2019, 12, 1973.

- Bénard, P.; Chahine, R. Storage of Hydrogen by Physisorption on Carbon and Nanostructured Materials. Scr. Mater. 2007, 56, 803–808.

- Ustinov, E.A.; Gavrilov, V.Y.; Mel’gunov, M.S.; Sokolov, V.V.; Berveno, V.P.; Berveno, A.V. Characterization of Activated Carbons with Low-Temperature Hydrogen Adsorption. Carbon 2017, 121, 563–573.

- Alhameedi, K.; Hussain, T.; Bae, H.; Jayatilaka, D.; Lee, H.; Karton, A. Reversible Hydrogen Storage Properties of Defect-Engineered C4N Nanosheets under Ambient Conditions. Carbon 2019, 152, 344–353.

- Heidarinejad, Z.; Dehghani, M.H.; Heidari, M.; Javedan, G.; Ali, I.; Sillanpää, M. Methods for Preparation and Activation of Activated Carbon: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 393–415.

- Blankenship, L.S.; Balahmar, N.; Mokaya, R. Oxygen-Rich Microporous Carbons with Exceptional Hydrogen Storage Capacity. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1545.

- Sdanghi, G.; Nicolas, V.; Mozet, K.; Schaefer, S.; Maranzana, G.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. A 70 MPa Hydrogen Thermally Driven Compressor Based on Cyclic Adsorption-Desorption on Activated Carbon. Carbon 2020, 161, 466–478.

- Chang, Y.-M.; Tsai, W.-T.; Li, M.-H. Characterization of Activated Carbon Prepared from Chlorella-Based Algal Residue. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 184, 344–348.

- Akasaka, H.; Takahata, T.; Toda, I.; Ono, H.; Ohshio, S.; Himeno, S.; Kokubu, T.; Saitoh, H. Hydrogen Storage Ability of Porous Carbon Material Fabricated from Coffee Bean Wastes. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 580–585.

- Jin, H.; Lee, Y.S.; Hong, I. Hydrogen Adsorption Characteristics of Activated Carbon. Catal. Today 2007, 120, 399–406.

- Jordá-Beneyto, M.; Suárez-García, F.; Lozano-Castelló, D.; Cazorla-Amorós, D.; Linares-Solano, A. Hydrogen Storage on Chemically Activated Carbons and Carbon Nanomaterials at High Pressures. Carbon 2007, 45, 293–303.

- Sharon, M.; Soga, T.; Afre, R.; Sathiyamoorthy, D.; Dasgupta, K.; Bhardwaj, S.; Sharon, M.; Jaybhaye, S. Hydrogen Storage by Carbon Materials Synthesized from Oil Seeds and Fibrous Plant Materials. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2007, 32, 4238–4249.

- Zhou, L.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y. Enhanced Storage of Hydrogen at the Temperature of Liquid Nitrogen. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2004, 29, 319–322.

- Lamari, F.; Aoufi, A.; Malbrunot, P.; Levesque, D. Hydrogen Adsorption in the NaA Zeolite: A Comparison Between Numerical Simulations and Experiments. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 5991–5999.

- Oriňáková, R.; Oriňák, A. Recent Applications of Carbon Nanotubes in Hydrogen Production and Storage. Fuel 2011, 90, 3123–3140.

- Fan, Y.-Y.; Kaufmann, A.; Mukasyan, A.; Varma, A. Single- and Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes Produced Using the Floating Catalyst Method: Synthesis, Purification and Hydrogen up-Take. Carbon 2006, 44, 2160–2170.

- Guldi, D.M.; Rahman, G.M.A.; Zerbetto, F.; Prato, M. Carbon Nanotubes in Electron Donor–Acceptor Nanocomposites. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005, 38, 871–878.

- Kaskun, S.; Akinay, Y.; Kayfeci, M. Improved Hydrogen Adsorption of ZnO Doped Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020, 45, 34949–34955.

- Rashidi, A.M.; Nouralishahi, A.; Khodadadi, A.A.; Mortazavi, Y.; Karimi, A.; Kashefi, K. Modification of Single Wall Carbon Nanotubes (SWNT) for Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 9489–9495.

- Zhao, T.; Ji, X.; Jin, W.; Yang, W.; Li, T. Hydrogen Storage Capacity of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Prepared by a Modified Arc Discharge. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostructures 2017, 25, 355–358.

- Silambarasan, D.; Surya, V.J.; Iyakutti, K. Experimental Investigation of Hydrogen Storage in Single Walled Carbon Nanotubes Functionalized with Borane. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 3574–3579.

- Silambarasan, D.; Surya, V.J.; Vasu, V.; Iyakutti, K. Reversible and Reproducible Hydrogen Storage in Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Functionalized with Borane. In Carbon Nanotubes—Recent Progress Rahman; Rahman, M.M., Asiri, A.M., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018; ISBN 978-1-78923-053-6.

- Barghi, S.H.; Tsotsis, T.T.; Sahimi, M. Chemisorption, Physisorption and Hysteresis during Hydrogen Storage in Carbon Nanotubes. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 1390–1397.

- Lee, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J. Influence of the Pore Size in Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on the Hydrogen Storage Behaviors. J. Solid State Chem. 2012, 194, 307–312.

- Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.-Z.; Xu, S.-T.; Cheng, H.-M. Hydrogen Storage in Carbon Nanotubes Revisited. Carbon 2010, 48, 452–455.

- Mosquera, E.; Diaz-Droguett, D.E.; Carvajal, N.; Roble, M.; Morel, M.; Espinoza, R. Characterization and Hydrogen Storage in Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Grown by Aerosol-Assisted CVD Method. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2014, 43, 66–71.

- Mosquera-Vargas, E.; Tamayo, R.; Morel, M.; Roble, M.; Díaz-Droguett, D.E. Hydrogen Storage in Purified Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes: Gas Hydrogenation Cycles Effect on the Adsorption Kinetics and Their Performance. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08494.

- Lin, K.-S.; Mai, Y.-J.; Li, S.-R.; Shu, C.-W.; Wang, C.-H. Characterization and Hydrogen Storage of Surface-Modified Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes for Fuel Cell Application. J. Nanomater. 2012, 2012, 939683.

- Chambers, A.; Park, C.; Baker, R.T.K.; Rodriguez, N.M. Hydrogen Storage in Graphite Nanofibers. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 4253–4256.

- Lueking, A.D.; Yang, R.T.; Rodriguez, N.M.; Baker, R.T.K. Hydrogen Storage in Graphite Nanofibers: Effect of Synthesis Catalyst and Pretreatment Conditions. Langmuir 2004, 20, 714–721.

- Jain, P.; Fonseca, D.A.; Schaible, E.; Lueking, A.D. Hydrogen Uptake of Platinum-Doped Graphite Nanofibers and Stochastic Analysis of Hydrogen Spillover. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 1788–1800.

- Lueking, A.; Pan, L.; Narayanan, D.; Burgess Clifford, C. Effect of Expanded Graphite Lattice in Exfoliated Graphite Nanofibers on Hydrogen Storage. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 12710–12717.

- Huang, C.-W.; Wu, H.-C.; Li, Y.-Y. Hydrogen Storage in Platelet Graphite Nanofibers. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2007, 58, 219–223.

- Browning, D.J.; Gerrard, M.L.; Lakeman, J.B.; Mellor, I.M.; Mortimer, R.J.; Turpin, M.C. Studies into the Storage of Hydrogen in Carbon Nanofibers: Proposal of a Possible Reaction Mechanism. Nano Lett. 2002, 2, 201–205.

- Kim, B.-J.; Lee, Y.-S.; Park, S.-J. Preparation of Platinum-Decorated Porous Graphite Nanofibers, and Their Hydrogen Storage Behaviors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2008, 318, 530–533.

- Gupta, B.K.; Srivastava, O.N. High-Yield Production of Graphitic Nanofibers. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2008, 33, 2975–2979.

- Nechaev, Y.S.; Denisov, E.A.; Cheretaeva, A.O.; Shurygina, N.A.; Kostikova, E.K.; Öchsner.A.; Davydov, S.Y. On the Problem of “Super” Storage of Hydrogen in Graphite Nanofibers. C. 2022, 8, 23.

- Alekseeva, O.K.; Pushkareva, I.V.; Pushkarev, A.S.; Fateev, V.N. Graphene and Graphene-Like Materials for Hydrogen Energy. Nanotechnolog. Russ. 2020, 15, 273–300.

- Ivanovskii, A.L. Graphene-Based and Graphene-like Materials. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2012, 81, 571.

- Dhar, P.; Gaur, S.S.; Kumar, A.; Katiyar, V. Cellulose Nanocrystal Templated Graphene Nanoscrolls for High Performance Supercapacitors and Hydrogen Storage: An Experimental and Molecular Simulation Study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3886.

- Wei, L.; Mao, Y. Enhanced Hydrogen Storage Performance of Reduced Graphene Oxide Hybrids with Nickel or Its Metallic Mixtures Based on Spillover Mechanism. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2016, 41, 11692–11699.

- Zhou, C.; Szpunar, J.A.; Cui, X. Synthesis of Ni/Graphene Nanocomposite for Hydrogen Storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 15232–15241.

- Arjunan, A.; Viswanathan, B.; Nandhakumar, V. Heteroatom Doped Multi-Layered Graphene Material for Hydrogen Storage Application. Graphene 2016, 5, 39–50.

- Muthu, R.N.; Rajashabala, S.; Kannan, R. Facile Synthesis and Characterization of a Reduced Graphene Oxide/Halloysite Nanotubes/Hexagonal Boron Nitride (RGO/HNT/h-BN) Hybrid Nanocomposite and Its Potential Application in Hydrogen Storage. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 79072–79084.

- Klechikov, A.G.; Mercier, G.; Merino, P.; Blanco, S.; Merino, C.; Talyzin, A.V. Hydrogen Storage in Bulk Graphene-Related Materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2015, 210, 46–51.

- Kag, D.; Luhadiya, N.; Patil, N.D.; Kundalwal, S.I. Strain and Defect Engineering of Graphene for Hydrogen Storage via Atomistic Modelling. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 22599–22610.

- Ao, Z.; Dou, S.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, G. Hydrogen Storage in Porous Graphene with Al Decoration. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 16244–16251.

- Langmi, H.W.; Book, D.; Walton, A.; Johnson, S.R.; Al-Mamouri, M.M.; Speight, J.D.; Edwards, P.P.; Harris, I.R.; Anderson, P.A. Hydrogen Storage in Ion-Exchanged Zeolites. J. Alloys Compd. 2005, 404–406, 637–642.

- Dong, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Li, J. Hydrogen Storage in Several Microporous Zeolites. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2007, 32, 4998–5004.

- Georgiev, D.; Bogdanov, B.; Angelova, K.; Markovska, I.; Hristov, Y. Synthetic Zeolites-Structure, Clasification, Current Trends In Zeolite Synthesis. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference, Stara Zagora, Bulgaria, 4–5 June 2009.

- Khaleque, A.; Alam, M.M.; Hoque, M.; Mondal, S.; Haider, J.B.; Xu, B.; Johir, M.A.H.; Karmakar, A.K.; Zhou, J.L.; Ahmed, M.B.; et al. Zeolite Synthesis from Low-Cost Materials and Environmental Applications: A Review. Environ. Adv. 2020, 2, 100019.

- Bowen, T.C.; Noble, R.D.; Falconer, J.L. Fundamentals and Applications of Pervaporation through Zeolite Membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 2004, 245, 1–33.

- Gangu, K.K.; Maddila, S.; Mukkamala, S.B.; Jonnalagadda, S.B. Synthesis, Structure, and Properties of New Mg(II)-Metal–Organic Framework and Its Prowess as Catalyst in the Production of 4H-Pyrans. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 2917–2924.

- Gangu, K.K.; Dadhich, A.S.; Mukkamala, S.B. Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Fluorescent Properties of Two Metal-Organic Frameworks Constructed from Cd(II) and 2,6-Naphthalene Dicarboxylic Acid. Inorg. Nano-Met. Chem. 2017, 47, 313–319.

- Bétard, A.; Fischer, R.A. Metal–Organic Framework Thin Films: From Fundamentals to Applications. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1055–1083.

- Sun, W.-F.; Sun, Y.-X.; Zhang, S.-T.; Chi, M.-H. Hydrogen Storage, Magnetism and Electrochromism of Silver Doped FAU Zeolite: First-Principles Calculations and Molecular Simulations. Polymers 2019, 11, 279.

- Silva, A.R.M.; Alexandre, J.Y.N.H.; Souza, J.E.S.; Neto, J.G.L.; de Sousa Júnior, P.G.; Rocha, M.V.P.; dos Santos, J.C.S. The Chemistry and Applications of Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) as Industrial Enzyme Immobilization Systems. Molecules 2022, 27, 4529.

- Zhou, H.C.; Long, J.R.; Yaghi, O.M. Introduction to Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 673–674.

- Chen, Z.; Kirlikovali, K.O.; Idrees, K.B.; Wasson, M.C.; Farha, O.K. Porous Materials for Hydrogen Storage. Chem 2022, 8, 693–716.

- Gross, K.J.; Carrington, K.R.; Barcelo, S.; Karkamkar, A.; Purewal, J.; Ma, S.; Zhou, H.-C.; Dantzer, P.; Ott, K.; Pivak, Y. Recommended Best Practices for the Characterization of Storage Properties of Hydrogen Storage Materials; EMN-HYMARC (EMN-HyMARC); National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2016.

- Akhtar, F.; Andersson, L.; Ogunwumi, S.; Hedin, N.; Bergström, L. Structuring Adsorbents and Catalysts by Processing of Porous Powders. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 34, 1643–1666.

- Ren, J.; North, B.C. Shaping Porous Materials for Hydrogen Storage Applications: A. J. Technol. 2014, 3, 13.

- Adhikari, A.K.; Lin, K.-S.; Tu, M.-T. Hydrogen Storage Capacity Enhancement of MIL-53(Cr) by Pd Loaded Activated Carbon Doping. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 63, 463–472.

- Musyoka, N.M.; Ren, J.; Annamalai, P.; Langmi, H.W.; North, B.C.; Mathe, M.; Bessarabov, D. Synthesis of a Hybrid MIL-101(Cr)/ZTC Composite for Hydrogen Storage Applications. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2016, 42, 5299–5307.

- Naeem, A.; Ting, V.P.; Hintermair, U.; Tian, M.; Telford, R.; Halim, S.; Nowell, H.; Hołyńska, M.; Teat, S.J.; Scowen, I.J.; et al. Mixed-Linker Approach in Designing Porous Zirconium-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks with High Hydrogen Storage Capacity. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 7826–7829.

- Li, J.-P.; Ma, Y.-Q.; Geng, L.-H.; Li, Y.-H.; Yi, F.-Y. A Highly Stable Porous Multifunctional Co(Ii) Metal–Organic Framework Showing Excellent Gas Storage Applications and Interesting Magnetic Properties. CrystEngComm 2015, 17, 6471–6475.

- Gómez-Gualdrón, D.A.; Moghadam, P.Z.; Hupp, J.T.; Farha, O.K.; Snurr, R.Q. Application of Consistency Criteria to Calculate BET Areas of Micro-and Mesoporous Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 215–224.

- Chen, Z.; Mian, M.R.; Lee, S.-J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Kirlikovali, K.O.; Shulda, S.; Melix, P.; Rosen, A.S.; Parilla, P.A. Fine-Tuning a Robust Metal–Organic Framework toward Enhanced Clean Energy Gas Storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 18838–18843.

- Lim, W.-X.; Thornton, A.W.; Hill, A.J.; Cox, B.J.; Hill, J.M.; Hill, M.R. High Performance Hydrogen Storage from Be-BTB Metal–Organic Framework at Room Temperature. Langmuir 2013, 29, 8524–8533.

- Gu, K.; Wei, F.; Cai, Y.; Lin, S.; Guo, H. Dynamics of Initial Hydrogen Spillover from a Single Atom Platinum Active Site to the Cu(111) Host Surface: The Impact of Substrate Electron–Hole Pairs. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 8423–8429.

- Conner, W.C.J.; Falconer, J.L. Spillover in Heterogeneous Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 759–788.

- Shen, H.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, C. Magic of Hydrogen Spillover: Understanding and Application. Green Energy Environ. 2022, 7, 1161–1198.

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, Q.; He, H. Synergistic Effect of Hydrogen Spillover and Nano-Confined AlH3 on Room Temperature Hydrogen Storage in MOFs: By GCMC, DFT and Experiments. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2023, in press.

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.T. Significantly Enhanced Hydrogen Storage in Metal–Organic Frameworks via Spillover. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 726–727.

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.T. Hydrogen Storage in Metal–Organic Frameworks by Bridged Hydrogen Spillover. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8136–8137.

- Sumida, K.; Horike, S.; Kaye, S.S.; Herm, Z.R.; Queen, W.L.; Brown, C.M.; Grandjean, F.; Long, G.J.; Dailly, A.; Long, J.R. Hydrogen Storage and Carbon Dioxide Capture in an Iron-Based Sodalite-Type Metal–Organic Framework (Fe-BTT) Discovered via High-Throughput Methods. Chem. Sci. 2010, 1, 184–191.

- Ibarra, I.A.; Yang, S.; Lin, X.; Blake, A.J.; Rizkallah, P.J.; Nowell, H.; Allan, D.R.; Champness, N.R.; Hubberstey, P.; Schröder, M. Highly Porous and Robust Scandium-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks for Hydrogen Storage. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 8304–8306.

- Gómez-Gualdrón, D.A.; Wang, T.C.; García-Holley, P.; Sawelewa, R.M.; Argueta, E.; Snurr, R.Q.; Hupp, J.T.; Yildirim, T.; Farha, O.K. Understanding Volumetric and Gravimetric Hydrogen Adsorption Trade-off in Metal–Organic Frameworks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 33419–33428.

- Zhang, X.; Lin, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Liang, B.; Yildirim, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W.; Chen, B. Optimization of the Pore Structures of MOFs for Record High Hydrogen Volumetric Working Capacity. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1907995.

- Chen, Z.; Li, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, P.; Wasson, M.C.; Islamoglu, T.; Stoddart, J.F.; Farha, O.K. Reticular Access to Highly Porous Acs-MOFs with Rigid Trigonal Prismatic Linkers for Water Sorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 2900–2905.

- Panella, B.; Hirscher, M.; Pütter, H.; Müller, U. Hydrogen Adsorption in Metal–Organic Frameworks: Cu-MOFs and Zn-MOFs Compared. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2006, 16, 520–524.

- Yan, X.; Komarneni, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, Z. Extremely Enhanced CO2 Uptake by HKUST-1 Metal–Organic Framework via a Simple Chemical Treatment. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 183, 69–73.

- Lin, K.-S.; Adhikari, A.K.; Ku, C.-N.; Chiang, C.-L.; Kuo, H. Synthesis and Characterization of Porous HKUST-1 Metal Organic Frameworks for Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2012, 37, 13865–13871.

- Kim, J.; Shapiro, L.; Flynn, A. The Clinical Application of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Cardiac Stem Cells as a Therapy for Cardiovascular Disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 151, 8–15.

- Gygi, D.; Bloch, E.D.; Mason, J.A.; Hudson, M.R.; Gonzalez, M.I.; Siegelman, R.L.; Darwish, T.A.; Queen, W.L.; Brown, C.M.; Long, J.R. Hydrogen Storage in the Expanded Pore Metal–Organic Frameworks M2(Dobpdc) (M = Mg, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Zn). Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 1128–1138.

- Viditha, V.; Srilatha, K.; Himabindu, V. Hydrogen Storage Studies on Palladium-Doped Carbon Materials (AC, CB, CNMs) @ Metal–Organic Framework-5. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 9355–9363.

- Nechaev, Y.S.; Denisov, E.A.; Cheretaeva, A.O.; Shurygina, N.A.; Kostikova, E.K.; Öchsner.A.; Davydov, S.Y. On the Problem of “Super” Storage of Hydrogen in Graphite Nanofibers. C. 2022, 8, 23.

- Li, S.; Pasc, A.; Fierro, V.; Celzard, A. Hollow carbon spheres, synthesis and applications – a review. Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 2016, 4, 12686-12713.

- Park, C.H.; Koo, W.T.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, J.; Jang, J.S.; Yun, H.; Kim, I.D.; Kim, B.J. Hydrogen Sensors Based on MoS2 Hollow Architectures Assembled by Pickering Emulsion. ACS Nano. 2020, 14, 9652-9661.

- Ryoo, R.; Joo, S.H.; Jun, S. Synthesis of highly ordered carbon molecular sieves via template-mediated structural transformation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 1999, 103, 7743-7746.

- Jeong, G.; Kim, T.; Park, S.D.; Yoo, M.J.; Park, C.H.; Yang, H. N, S‐Codoped Carbon Dots‐Based Reusable Solvatochromic Organogel Sensors for Detecting Organic Solvents. Macromolecular Rapid Communications. 2024, 45, 2300542.

- Le, T.H.; Kim, M.P.; Park, C.H.; Tran, Q.N. Recent Developments in Materials for Physical Hydrogen Storage: A Review. Materials. 2024, 17, 666.

- Choi, M.; Na, K.; Kim, J.; Sakamoto, Y.; Terasaki, O.; Ryoo, R. Stable single-unit-cell nanosheets of zeolite MFI as active and long-lived catalysts. Nature. 2009, 461, 246-249.

- Maqbool, M.; Akhter, T.; Faheem, M.; Nadeem, S.; Park, C.H. CO 2 free production of ethylene oxide via liquid phase epoxidation of ethylene using niobium oxide incorporated mesoporous silica material as the catalyst. RSC Advances. 2023, 13, 1779-1786.

- Afzal, I.; Akhter, T.; Hassan, S.U.; Lee, H.K.; Razzaque, S.; Mahmood, A.; Al-Masry, W.; Lee, H.; Park, C.H. Logical Optimization of Metal–Organic Frameworks for Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants in Water via Box–Behnken Design. ACS EST Water. 2024, 4, 648–660.

- Siddiqa, A.; Akhter, T.; Faheem, M.; Razzaque, S.; Mahmood, A.; Al-Masry, W.; Nadeem, S.; Hassan, S.U.; Yang, H.; Park, C.H. Bismuth-Rich Co/Ni Bimetallic Metal–Organic Frameworks as Photocatalysts toward Efficient Removal of Organic Contaminants under Environmental Conditions. Micromachines. 2023, 14, 899.

More

Information

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

18 Apr 2024

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No