Infections on tattoos can manifest either as pyogenic or nonpyogenic. In contemporary times, due to standard hygiene practices and modern aseptic tattooing techniques, the majority of infections are typically superficial (acute superficial pyogenic infections, including folliculitis, impetigo, and ecthyma), of bacterial origin, and manifest within a few days post-tattooing

[3][6][7]. One Danish study revealed that 10% of the unopened tattoo ink stock bottles were contaminated with a range of bacteria, including both pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains

[7][8]. Examples of isolated strains include

Pseudomonas species,

Staphylococcus species,

Streptococcus salivarius,

Streptococcus sanguinis,

Enterococcus faecium, and

Acinetobacter species

[7][8]. Additionally, 28% of the analyzed stock bottles were found to be inadequately sealed

[7][8].

Table 1. Bacterial and mycobacterial tattoo-related side effects and clinical measures.

Side

Effects |

Bacterial |

Mycobacterial |

| Clinical measures |

Staphylococcus aureus/Streptococcus pyogenes/Clostridium difficile/Pseudomonas aeruginosa [3][15] |

Mycobacterium tuberculosis/Mycobacterium bovis [3][6][19][20][21] |

Mycobacterium chelonae/Mycobacterium abscessus/Mycobacterium fortuitum [22][23][24] |

Mycobacterium mageritense [3][25][26] |

Mycobacterium leprae [1][3][27] |

| Standard bacterial infection management |

Multidrug therapy administered in two phases [28]:

Isoniazid

Rifampicin

Pyrazinamide

Ethambutol or Streptomycin |

Macrolide antibiotics [29]

(Clarithromycin)

4 months in mild cases

6–12 months in severe cases |

Antibiotic therapy [29]:

Amikacin

Imipenem

Cefoxitin

Fluroquinolones

Sulfonamides |

Paucibacillary disease [30]:

Dapsone + Rifampicin + Clofazimine for 6 months |

Multibacillary disease [30]:

Dapsone + Rifampicin + Clofazimine for 12 months |

Rifampicin resistance [30]:

24 months treatment broken down as 6 months of Clofazimine + Ofloxacin and Minocycline followed by 18 months of Clofazimine + Ofloxacin or Minocycline |

Dapsone resistance [30]:

Clofazimine + Rifampicin for 6 months |

In recent decades, one case of secondary syphilis occurring within a tattoo has been reported

[3][31]. In the 19th century, syphilis was more frequently described in the context of tattoos

[3][31]. During that period, tattoo artists often moistened needles with saliva or used nonsterile or previously used needles, potentially leading to the contamination of patients with

Treponema pallidum [3][31].

3. Mycobacterial Infections

Tattoo-inoculated mycobacterial infections encompass tuberculosis, leprosy, and atypical mycobacteria such as

Mycobacterium chelonae and

Mycobacterium abscessus [22][23][24].

Tattooing can lead to the development of primary cutaneous tuberculosis

[3][6][20][24]. This occurs when individuals lacking previous immunity are inoculated with

Mycobacterium tuberculosis or

Mycobacterium bovis [3][6][19][20][21]. Within 2–4 weeks, an erythematous papule or nodule emerges, eventually progressing to a superficial ulcer known as a tuberculous chancre

[3][6][19][20][21]. Often, painless regional lymphadenopathy ensues within 3 to 8 weeks

[3][6][19][20][21]. In cases where the patient’s immune system is compromised, there is a risk of progression to lupus vulgaris and tuberculosis cutis verrucose, or even hematogenous spread

[3][19][20][21]. Differential diagnoses include foreign-body granuloma, sarcoidosis, inoculation leprosy, tertiary syphilis, and infections with atypical mycobacteria

[6]. The histological examination typically reveals epithelioid histiocytes, Langhans giant cells, and tuberculoid granulomas, with or without central caseous necrosis

[3][19][20][21]. A positive tuberculin test holds significant diagnostic value for primary tuberculosis

[6][19][20][21].

The treatment approach for cutaneous tuberculosis is consistent with that of systemic tuberculosis and involves multidrug therapy

[28]. Commonly used drugs include isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol or streptomycin, administered in two phases: the intensive one (which aims to rapidly reduce the burden of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis and typically spans about 8 weeks) and the continuation phase, designed to eradicate any remaining bacteria and extends for a duration of 9 to 12 months

[28] (

Table 1). Strict adherence to the treatment regimen is crucial for a successful cure

[28].

Various factors influence the outcomes of treatment, including the patient’s immunity, overall health, disease stage, type of cutaneous lesions, treatment adherence, duration of therapy, and potential side effects

[28].

Atypical mycobacterial infections, particularly with

Mycobacterium chelonae, appear to be an emerging complication

[3][32][33][34][35]. This occurrence is particularly associated with the preparation of grey ink, which is obtained by diluting black ink with water

[3][33]. If the water used in this process is contaminated with

Mycobacterium chelonae, a bacterium commonly found in nonsterile water, it can lead to infections

[3][33]. Less commonly, skin infections can be caused by other mycobacterial species, such as

Mycobacterium haemophilum, Mycobacterium abscessus, Mycobacterium immunogenum, Mycobacterium massiliense, Mycobacterium mageritense, and

Mycobacterium fortuitum [3][25][26] (

Table 1). Interestingly, mycobacterial infections tend to manifest more frequently in the grey or black areas of a tattoo

[3][33]. Clinically, lesions present as chronic papules, pustules, lichenoid plaques, and plaques with scales, typically developing within 1 to 3 weeks after the procedure

[3][33]. Ulcerated nodules primarily confined to the tattooed area have also been reported

[3][33].

For skin and soft-tissue infections caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria, a prolonged treatment regimen involving combination therapy with at least two susceptible antimicrobials is recommended to minimize the risk of antibiotic resistance

[29]. Typically, the recommended duration of therapy for mild cases is around 4 months, while severe cases may require treatment for 6–12 months

[29]. Macrolide antibiotics, with clarithromycin commonly included, are considered standard treatment for nontuberculous mycobacteria infections, including those associated with tattoos and involving

Mycobacterium chelonae,

Mycobacterium abscessus, and

Mycobacterium fortuitum [29]. However, it is important to note that

Mycobacterium mageritense is known to be resistant to macrolides due to the presence of the erythromycin ribosomal methylase gene, which imparts resistance to macrolide antibiotics

[29].

Mycobacterium mageritense generally exhibits susceptibility or intermediate susceptibility to amikacin, imipenem, cefoxitin, fluoroquinolones, and sulfonamides but is resistant to clarithromycin

[29]. It is essential to guide antibiotic therapy based on susceptibility testing

[29] (

Table 1).

Instances of tattoo inoculation with

Mycobacterium leprae are predominantly reported in regions where leprosy is endemic, and unhygienic tattooing practices are prevalent

[1][3][27]. The onset of leprosy after tattooing can vary significantly, occurring between 10 to 20 years post-tattooing

[1][3][27]. Outbreaks have been linked to the use of shared needles during unhygienic tattooing by roadside artists

[3][6][27]. Manifestation of leprosy skin lesions may occur 10 to 20 years after the initial inoculation, and the clinical presentation is primarily influenced by the immunologic status of the host

[3][6][27]. In cases where a mycobacterial infection is suspected, conducting a biopsy, tissue culture, and polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium species is recommended

[3][6][27]. Histologically, these reactions are characterized by the formation of suppurative granulomas with the presence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes

[3][6][27].

Treatment recommendations for leprosy in adults consist of long-term multidrug therapy: dapsone, rifampicin, and clofazimine for 6 months in paucibacillary disease and for 12 months in case of multibacillary disease

[30]. In case of rifampicin resistance, clofazimine plus at least two of minocycline, clarithromycin, and quinolone for 6 months is recommended, followed by an additional 18 months of clofazimine plus one of the aforementioned drugs

[30] (

Table 1).

4. Viral Infections

The transmission of infections such as verrucae, molluscum contagiosum virus, human papillomavirus (HPV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and hepatitis B (HBV) and C viruses (HCV) has been documented

[3][6] (

Figure 1 and

Table 2).

Figure 1. Multiple viral warts localized on the trunk.

Table 2. Viral, fungal, and parasitic tattoo-related side-effects and clinical measures.

| Side Effects |

Viral |

Fungal |

Parasitic |

| Clinical measures |

Viral warts [3][12][36][37][38] |

Molluscum contagiosum [3][12][36][37][38] |

HPV, HSV, HIV, HBV and HCV [3][6] |

Dermatophytes/Aspergillus fumigatus/Sporotrichosis/Zygomycosis/Acremonium fungi/Candida [3][6][31][39][40] |

Leishmania species [3] |

Firstline [41][42]:

Salicylic Acid

Cryotherapy |

First-line [43][44][45]:

Cryotherapy

Curetage

Cantharidin

Podophyllotoxin |

Multidisciplinary medical personnel (infectious disease specialist)

Antivirals as standard therapeutic approach |

Topical antifungals:

Clotrimazole

Econazole

Miconazole

Ketoconazole

Nystatin Terbinafine |

Cryotherapy

Photodynamic therapy

Imiquimod [46] |

Refractory warts [42]:

Topical immunotherapy (contact allergens, intralesional Bleomycin, Fluorouracil) |

Other [43][44][45][47][48][49][50][51]:

Imiquimod

Salicylic Acid

Topical retinoids |

Systemic antifungals:

Amphotericin B

Itraconazole

Fluconazole

Voriconazole

Terbinafine

Griseofulvin |

Intralesional or systemic antimonials [46]:

Sodium stibogluconate Meglumine antimoniate |

Other [41][42][52][53][54][55][56][57]:

Cantharidin

Imiquimod

Trichloroacetic acid

Pulsed dye laser

Intralesional

immunotheraphy

Surgery |

Other systemic therapies [46]:

AmphotericinB

Miltefosine

Pentamidin

Itraconazole

Fluconazole

Ketoconazole

Paromomycin

Zinc sulfate

Allopurinol |

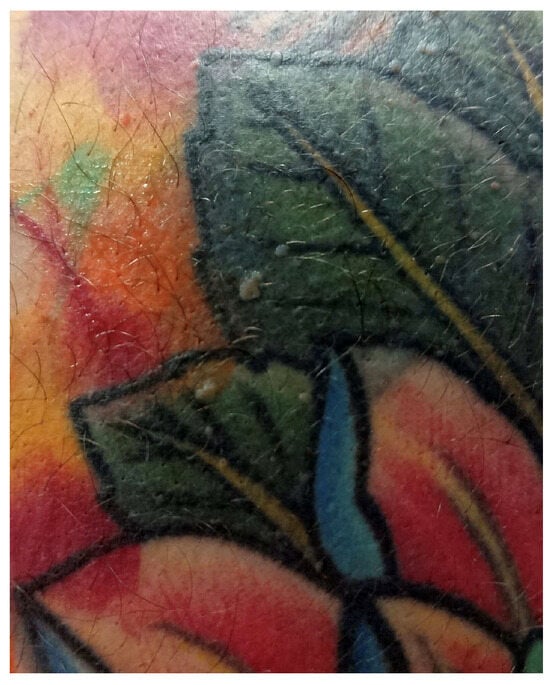

Viral warts and molluscum contagiosum lesions exhibit varying numbers and sizes, sometimes confined to a specific tattoo-ink color

[3][12][36][37][38] (

Figure 2). Onset may occur between 1 month and 10 years after tattooing

[3][12][36][37][38] (

Figure 3). The inoculation may be associated with contaminated instruments, alterations in local immunity related to the ink, or intense UV-light exposure

[3][12][36][37][38]. However, the most plausible hypothesis remains the pre-existence of microscopic skin lesions disseminated through the tattoo drawing by a Koebner phenomenon

[3][12][36][37][38]. When multiple viral lesions spontaneously appear within a tattoo, it may prompt testing for underlying immunodeficiencies

[3][58].

Figure 2. Clinical and dermoscopic features of viral warts localized on the right leg.

Figure 3. Clinical and dermoscopic features of a viral wart in a microtattooed eyebrow.

First-line treatment approaches for viral warts are salicylic acid and cryotherapy

[41][42]. Refractory warts could benefit from topical immunotherapy with contact allergens, intralesional bleomycin, and fluorouracil

[42] (

Table 2). A variety of other additional treatments include cantharidin, imiquimod, trichloroacetic acid, pulsed dye laser, intralesional immunotherapy, and surgery

[41][42][52][53][54][55][56][57] (

Table 2).

First-line therapies for molluscum contagiosum lesions include cryotherapy, curettage, cantharidin, and podophyllotoxin

[43][44][45] (

Table 2). Other treatment considerations involve imiquimod, salicylic acid, and topical retinoids

[43][44][45][47][48][49][50][51] (

Table 2).

Isolated cases of HPV and HSV within tattoos have been reported. HSV has been documented in people with cosmetically tattooed lips. These infections can either be transmitted during tattooing or reactivated from a previously dormant virus

[3][6]. The incubation period typically spans weeks to months

[3][6]. The triggering factor may be represented by a recent sunburn, suggesting that UV radiation could induce immunosuppression and activate HPV

[3][6].

Severe viral infections, including HIV, HBV, and HCV have been reported in association with tattooing, the majority of these reports involving tattoos performed in nonprofessional settings

[3][6]. With current hygiene regulations and tattoos administered by professional artists, the transmission of these viral infections is considered unlikely

[3][22]. Additionally, many individuals with HIV, HBV, or HCV have other potential modes of transmission, such as injection drug use

[3][6].

Antivirals represent the standard therapeutic approach, and the involvement of multidisciplinary medical personnel is advisable (Table 2).

5. Fungal Infections

Fungal infections following tattooing are infrequent. However, there have been rare cases of infections involving dermatophytes,

Aspergillus fumigatus, sporotrichosis, zygomycosis,

Acremonium fungi, or Candida

[3][6][31][39][40]. The possibility of fungal infections should be taken into consideration when cutaneous complications worsen with the use of topical corticosteroids

[3][6][31][39][40].

Antifungals, either systemic (amphotericin B, itraconazole, fluconazole, voriconazole, terbinafine, and griseofulvin) or topically applied (clotrimazole, econazole, miconazole, ketoconazole, nystatin, and terbinafine) represent the standard therapeutic approach (Table 2).

6. Parasitic Infections

Cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis emerging in tattoos are seldom documented, and all reported ones have been observed in individuals already diagnosed with visceral leishmaniasis or HIV, conditions associated with immunosuppression

[3]. The reuse of needles may represent a potential mode of transmission

[3].

Diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis relies on a meticulous assessment of the patient’s medical history and a detailed examination of the lesion’s clinical characteristics

[46]. In nonendemic areas, obtaining a comprehensive travel history is imperative, given the prolonged incubation period

[46]. Confirmation of the diagnosis entails the identification of the parasite through procedures such as biopsy or split skin smear

[46]. For a precise determination of the Leishmania species, especially in cases involving a risk of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques are employed

[46].

Therapy options include cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, imiquimod, and intralesional or systemic antimonials (sodium stibogluconate, meglumine antimoniate)

[46] (

Table 2). Other systemic employed therapies involve amphotericin B, miltefosine, pentamidine, antifungal drugs (itraconazole, fluconazole, ketoconazole), paromomycin, zinc sulfate, and allopurinol

[46].