Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alexandru Cosmin Pantazi | -- | 2384 | 2024-01-20 17:27:00 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 2384 | 2024-01-22 02:58:40 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Nori, W.; Kassim, M.A.K.; Helmi, Z.R.; Pantazi, A.C.; Brezeanu, D.; Brezeanu, A.M.; Penciu, R.C.; Serbanescu, L. Non-Pharmacological Pain Management in Labor. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/54148 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Nori W, Kassim MAK, Helmi ZR, Pantazi AC, Brezeanu D, Brezeanu AM, et al. Non-Pharmacological Pain Management in Labor. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/54148. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Nori, Wassan, Mustafa Ali Kassim Kassim, Zeena Raad Helmi, Alexandru Cosmin Pantazi, Dragos Brezeanu, Ana Maria Brezeanu, Roxana Cleopatra Penciu, Lucian Serbanescu. "Non-Pharmacological Pain Management in Labor" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/54148 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Nori, W., Kassim, M.A.K., Helmi, Z.R., Pantazi, A.C., Brezeanu, D., Brezeanu, A.M., Penciu, R.C., & Serbanescu, L. (2024, January 20). Non-Pharmacological Pain Management in Labor. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/54148

Nori, Wassan, et al. "Non-Pharmacological Pain Management in Labor." Encyclopedia. Web. 20 January, 2024.

Copy Citation

Childbirth is a remarkable, life-changing process and is frequently regarded as an excruciating, physically and emotionally demanding experience that women endure. Labor pain management poses a significant challenge for obstetricians and expectant mothers.

non-pharmacological pain management

pregnancy

mothers

labor

obstetrician efficacy

1. Introduction

Historically, labor pain has been recognized as an inherent part of childbirth, although approaches to its management have varied across cultures and time periods [1]. With the advent of modern medicine, the focus shifted toward pharmacological interventions. By the late 19th century, interventions such as chloroform and ether were used for labor pain, followed by the introduction of “twilight sleep” in the early 20th century—a combination of morphine and scopolamine that induced a state of semi-consciousness [2][3].

In the latter half of the 20th century, advances in anesthesia led to the widespread use of regional analgesics, such as epidurals and spinal blocks, for labor pain [4]. These methods became the gold standard in many high-income countries due to their effectiveness in reducing pain [5]. In recent decades, the use of opioids such as fentanyl and morphine has also become common [6]. Although they do not eliminate pain, they can help to make it more manageable. However, pharmacological pain management methods (PPM) have been associated with various side effects and risks despite their effectiveness. For example, epidurals can lead to a drop in blood pressure, fever, and a raised need for assisted delivery [7]. Moreover, they lengthen the labor’s duration. Opioids induce nausea and affect the neonate (breathing and heart tracing) if admitted too soon [8][9]. Pain is the norm of childbirth; reducing pain via drugs makes laboring women lose essential feedback, potentially leading to more prolonged labor or increased intervention. Some forms of PPM reduce a woman’s motility or the ability to take different positions to alleviate discomfort; this lack of control over pain is distressing to women [10]. Over the past few decades, a growing interest has been expressed in revisiting non-pharmacological pain management techniques (NPPM) to reduce labor pain [11][12]. This shift is driven by a confluence of factors, including increasing evidence of pharmacological interventions’ side effects and risks. Additionally, there has been a broader societal shift towards more patient-centered and holistic healthcare, emphasizing personal autonomy, shared decision-making, and natural and complementary therapies [13]. These trends have led to an increased interest in NPPM, which relieves pain and empowers women to actively engage in the birth experience. NPPMs have demonstrated encouraging outcomes in diminishing pain intensity and enhancing satisfaction and are commonly regarded as safe, with minimal adverse effects compared to pharmacological interventions [3][5][8].

2. Understanding Pain in Labor

The nature of pain experienced during labor undergoes modifications as the process progresses. During the first stage of labor, the primary source of pain is visceral in nature, originating mostly from the cervix, uterus, and adnexa. This pain is mediated by sympathetic fibers that transmit signals to the ganglia of the posterior nerve roots located at the T10-L1 spinal levels [5]. During the late first stage and early second stage of labor, pain arises from the distention and traction of the pelvic organs. The pudendal nerve is responsible for transmitting pain signals to the ganglia of the posterior nerve roots located at spinal levels S2 to S4. During the second stage of labor, the sensation of pain is elicited by the stretching of the perineal structures as the fetus descends [5][11]. Comprehending the complexities of labor pain goes beyond the physiological aspects; it necessitates an understanding of psychological and socio-cultural elements. It is crucial to grasp the multifaceted nature of labor pain to assess NPPM better. From a physiological standpoint, uterine contractions and cervical dilation are the main causes of labor pain, because they activate pain receptors (nociceptors) and send signals to the brain [11]. The intensity of labor pain can vary greatly among women, between different labors in the same woman, and it is affected by various factors such as the baby’s position, size, and the speed of labor [12]. On a psychological level, labor pain is influenced by a woman’s emotions, expectations, and previous experiences [13][14]. Fear and anxiety can heighten pain perception by increasing tension and resistance. As confidence, relaxation, the feeling of control in their labor, and continuous support are all less likely to result in severe pain, the women are more likely to cope and have a positive birth experience [15][16][17][18]. Psychological preparation for childbirth can reduce the need for analgesia and increase satisfaction with pain management [19][20]. Socio-cultural factors, cultural beliefs, and societal attitudes toward childbirth can influence a woman’s expectations and coping strategies. In some cultures, labor pain is viewed as a natural and empowering part of childbirth, while in others, it is seen as something to be avoided or feared [21][22]. Furthermore, social support is crucial during labor. Having a supportive companion can significantly improve a woman’s experience of pain and reduce her need for pharmacological analgesia [23][24].

3. Categorization of Non-Pharmacological Methods for Pain Relief in Labor

These can be categorized based on the mechanisms of action into physical, psychological, and complementary techniques.

3.1. Physical Modalities

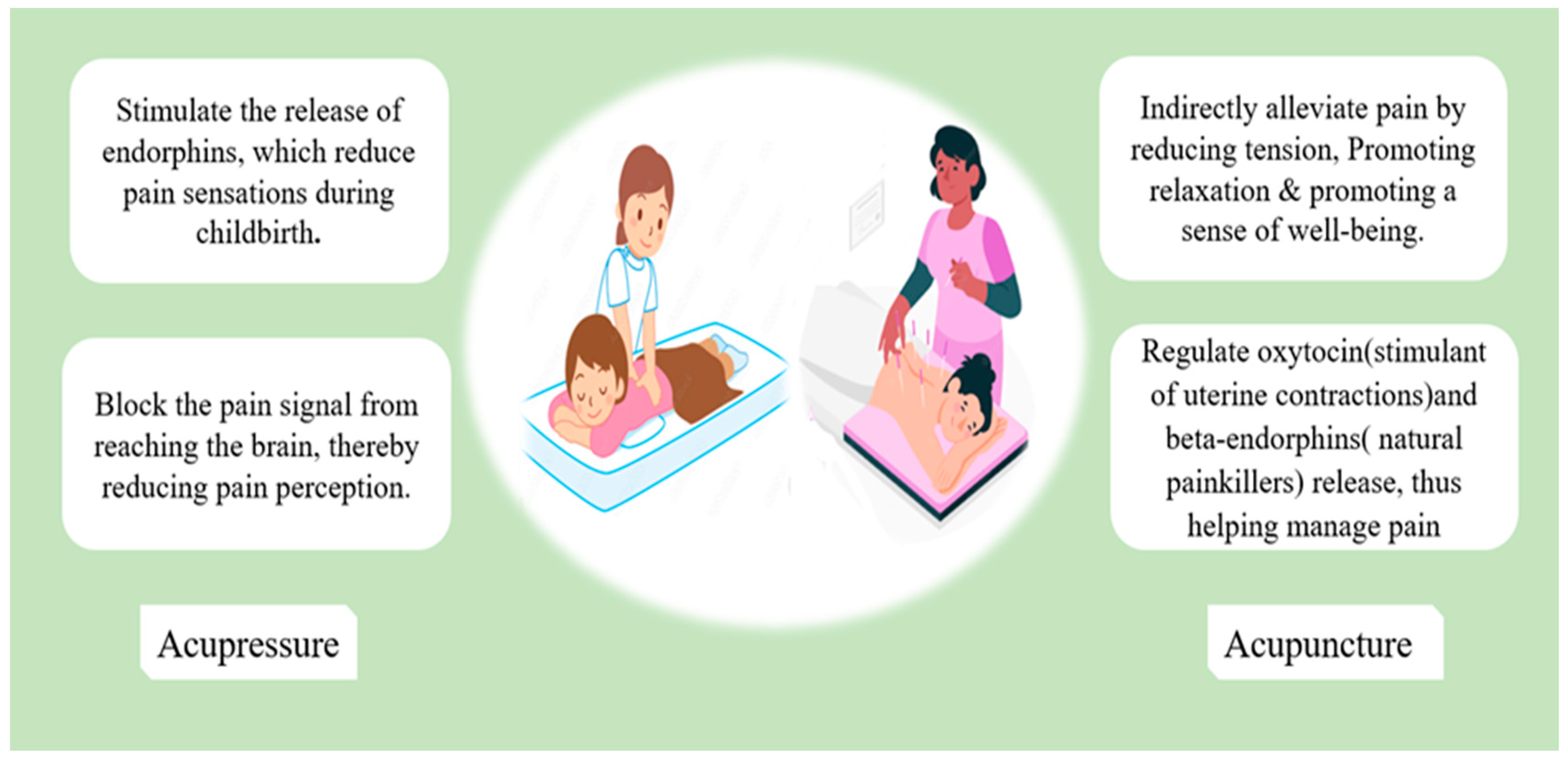

There are several physical methods listed under NPPM during labor. These methods include massage, pressure on precise anatomical locations, Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), water immersion, heat and cold therapy, breathing techniques, positioning, and movement [25][26]. The sub-types of each method, mechanism of action, perceived benefits, and supporting references are all summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Non-pharmacological pain management in labor: An in-depth analysis of physical modalities concerning the mechanism of action, perceived benefit, and the supporting references.

| Methods | Methods Sub-Types | Proposed Mechanism of Action | Perceived Benefit | Authors’ Name; Publication Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Massage |

|

|

|

Pawale et al. [27]; 2020 Silva Gallo et al. [28]: 2013 Eskandari F et al. [29]; 2022 |

| Pressure on precise anatomical locations |

|

|

|

Smith et al. [30]; 2020 Schlaeger et al. [31]; 2017 Eshraghi et al. [32]; 2021 |

| Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) |

|

|

|

Thuvarakan et al. [33]; 2020 Gibson et al. [34]; 2019 Daniel et al. [35]; 2021 |

| Water immersion |

|

|

|

Cluett et al. [36]; 2018 Carlsson et al. [37]; 2020 Cooper et al. [38]; 2022 |

| Heat therapy |

|

|

|

Goswami et al. [39]; 2022 Akbarzadeh et al. [40]; 2018 Akbarzadeh et al. [41]; 2016 Dastjerd et al. [42]; 2023 |

| Cold therapy |

|

|

|

Shirvani et al. [43]; 2014 Emine et al. [44]; 2022 Serap et al. [45]; 2022 |

| Breathing techniques |

|

|

|

Baljon et al. [46]; 2022 Issac et al. [47]; 2023 Yuksel H et al. [48]; 2017 Boaviagem et al. [49]; 2017 |

| Positioning and Movement |

|

|

|

Huang et al. [50]; 2019 Ondeck et al. [51]; 2019 Borges et al. [52]; 2021 Ali SA et al. [53]; 2018 |

Figure 1. The mechanisms that underlie acupressure’s positive effect in reducing labor pain.

3.2. Psychological Techniques

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) aims to identify and modify maladaptive thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. Moreover, CBT assists individuals in cultivating a perception of control in managing pain, fostering the acquisition of pain-coping strategies, and enhancing self-esteem [54]. CBT was used to manage labor pain; there was inconsistency in the reported literature; some discussed reduced psychological aspects of pain and improved satisfaction [55]. However, pain medication was still needed.

Others have discussed how CBT techniques significantly reduced pain intensity and labor duration [54].

Cognitive behavioral therapy helps individuals have a sense of control in coping with pain, develop pain-coping behaviors, and increase self-respect [54][56]. The main methods of CBT include:

-

Relaxation techniques;

-

Virtual reality (VR);

-

Music;

-

Distraction technique.

The main mechanism and benefits of each are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of non-pharmacological pain management in labor: An in-depth analysis of psychological modalities, concerning the mechanism of action, perceived benefit, and the supporting references.

| Methods | Methods Sub-Types | Proposed Mechanism of Action | Perceived Benefit | Authors’ Name; Publication Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relaxation technique |

|

Progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, and visualization have been found to be effective in mitigating anxiety and fostering tranquility throughout labor. |

|

Smith et al. [15]; 2018 Zhang et al. [57] Jahdi et al. [58]; 2017 |

| Virtual reality (VR) |

|

|

|

Massov et al. [59]; 2021 Musters et al. [60]; 2023 Baradwan et al. [61]; 2022Xu et al. [62]; 2022 |

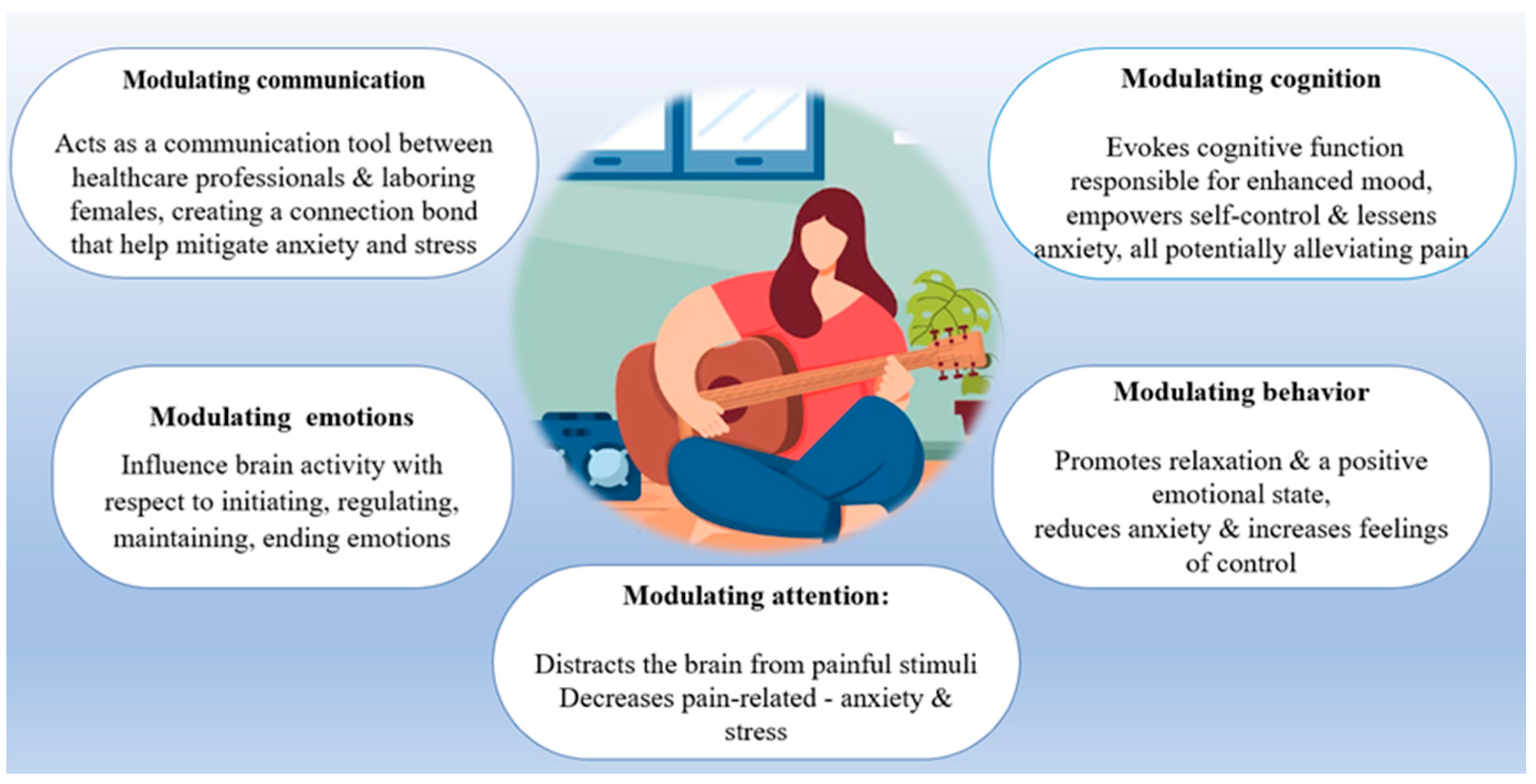

| Music | -- |

|

|

Timmerman et al. [63]; 2023 Estrella-Juarez et al. [64]; 2023 Chehreh et al. [65]; 2023 García González et al. [66]; 2018 |

| Distraction |

|

|

|

Ireland et al. [67]; 2016 Amiri et al. [68]; 2019 Melillo et al. [69]; 2022 |

Figure 2. The main pathways by which music conducts its beneficial effect in alleviating labor pain.

3.3. Complementary and Alternative Approaches

Over the past decade, there has been a growing scholarly focus on literature examining the role of Complementary and Alternative Approaches (CAA) in mitigating pain during childbirth [70]. CAA exhibits a higher prevalence among women within the reproductive age range [71]. The utilization of this intervention during childbirth is quite prevalent, as indicated by a survey conducted in Australia, with a reported rate of 75% [72]. Complementary and Alternative Medicine is a term employed by the U.S. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health to denote a range of practices that can be utilized in conjunction with conventional and established medical care (complementary) or as a substitute for it (alternative) [73]. An in-depth analysis of complementary and alternative approaches concerning the mechanism of action, perceived benefit, and the supporting references [74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89] are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of non-pharmacological pain management in labor: An in-depth analysis of complementary and alternative approaches concerning the mechanism of action, perceived benefit, and the supporting references.

| Methods | Methods Sub-Types | Proposed Mechanism of Action | Perceived Benefit | Authors’ Name; Publication Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypnosis |

|

|

|

Madden et al. [74]; 2016 Cyna et al. [75]; 2013 Downe et al. [76]; 2015 |

| Integration of religion/health and well-being |

|

|

|

McLaren H et al. [77]; 2021 Desmawati et al. [78]; 2019 Kocak et al. [79]; 2022 |

| Dancing | -- |

|

|

Abdolahian et al. [80]; 2014 Akin et al. [81]; 2020 |

| Aromatherapy | Essential oils may be given as:

|

|

|

Tabatabaeichehr et al. [82]; 2020 Sirkeci et al. [83]; 2023 Hamdamian et al. [84]; 2018 |

| Photomodulation | -- | Irradiation induces.

|

|

Traverzim et al. [85]: 2021 Traverzim et al. [86]; 2018 |

| Support therapy |

|

|

|

Akbas et al. [87]; 2022 Bohren et al. [88]; 2017 Ip et al. [89]; 2009 |

References

- Jones, L. Pain Management for Women in Labour: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. J. Evid. Based Med. 2012, 5, 101–102.

- Edwards, M.L.; Jackson, A.D. The Historical Development of Obstetric Anesthesia and Its Contributions to Perinatology. Am. J. Perinatol. 2017, 34, 211–216.

- Skowronski, G.A. Pain Relief in Childbirth: Changing Historical and Feminist Perspectives. Anaesth. Intensiv. Care 2015, 43, 25–28.

- Wong, C.A. Advances in Labor Analgesia. Int. J. Women’s Health 2009, 1, 139–154.

- Boselli, E.; Hopkins, P.; Lamperti, M.; Estèbe, J.P.; Fuzier, R.; Biasucci, D.G.; Disma, N.; Pittiruti, M.; Traškaitė, V.; Macas, A.; et al. European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Guidelines on Peri-Operative Use of Ultrasound for Regional Anaesthesia (PERSEUS Regional Anesthesia): Peripheral Nerves Blocks and Neuraxial Anaesthesia. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2021, 38, 219–250.

- Smith, L.A.; Burns, E.; Cuthbert, A. Parenteral Opioids for Maternal Pain Management in Labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD007396.

- Callahan, E.C.; Lee, W.; Aleshi, P.; George, R.B. Modern Labor Epidural Analgesia: Implications for Labor Outcomes and Maternal-Fetal Health. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, S1260–S1269.

- Marcum, Z.A.; Griend, J.P.; Linnebur, S.A. FDA Drug Safety Communications: A Narrative Review and Clinical Considerations for Older Adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharmacother. 2012, 10, 264–271.

- Zipursky, J.S.; Gomes, T.; Everett, K.; Calzavara, A.; Paterson, J.M.; Austin, P.C.; Mamdani, M.M.; Ray, J.G.; Juurlink, D.N. Maternal Opioid Treatment after Delivery and Risk of Adverse Infant Outcomes: Population Based Cohort Study. BMJ 2023, 380, e074005.

- Halliday, L.; Nelson, S.M.; Kearns, R.J. Epidural Analgesia in Labor: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 159, 356–364.

- Zuarez-Easton, S.; Erez, O.; Zafran, N.; Carmeli, J.; Garmi, G.; Salim, R. Pharmacologic and Nonpharmacologic Options for Pain Relief during Labor: An Expert Review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, S1246–S1259.

- Siyoum, M.; Mekonnen, S. Labor Pain Control and Associated Factors among Women Who Gave Birth at Leku Primary Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 619.

- Beigi, S.; Valiani, M.; Alavi, M.; Mohamadirizi, S. The Relationship between Attitude toward Labor Pain and Length of the First, Second, and Third Stages in Primigravida Women. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2019, 8, 130.

- Komariah, N.; Wahyuni, S. The Relation Between Labor Pain with Maternal Anxiety. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Health, Social Sciences and Technology (ICoHSST 2020), Palembang, Indonesia, 20–21 October 2020; Volume 521.

- Smith, C.A.; Levett, K.M.; Collins, C.T.; Armour, M.; Dahlen, H.G.; Suganuma, M. Relaxation Techniques for Pain Management in Labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD009514.

- Cook, K.; Loomis, C. The Impact of Choice and Control on Women’s Childbirth Experiences. J. Perinat. Educ. 2012, 21, 158–168.

- Lunda, P.; Minnie, C.S.; Benadé, P. Women’s Experiences of Continuous Support during Childbirth: A Meta-Synthesis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 167.

- Stjernholm, Y.V.; Charvalho, P.d.S.; Bergdahl, O.; Vladic, T.; Petersson, M. Continuous Support Promotes Obstetric Labor Progress and Vaginal Delivery in Primiparous Women—A Randomized Controlled Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 582823.

- Makvandi, S.; Mirzaiinajmabadi, K.; Tehranian, N.; Esmily, H.; Mirteimoori, M. The Effect of Normal Physiologic Childbirth on Labor Pain Relief: An Interventional Study in Mother-Friendly Hospitals. Maedica 2018, 13, 286.

- Hoffmann, L.; Hilger, N.; Banse, R. The Mindset of Birth Predicts Birth Outcomes: Evidence from a Prospective Longitudinal Study. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 53, 857–871.

- Whitburn, L.Y.; Jones, L.E.; Davey, M.A.; McDonald, S. The Nature of Labour Pain: An Updated Review of the Literature. Women Birth 2018, 32, 28–38.

- Navarro-Prado, S.; Sánchez-Ojeda, M.; Marmolejo-Martín, J.; Kapravelou, G.; Fernández-Gómez, E.; Martín-Salvador, A. Cultural Influence on the Expression of Labour-Associated Pain. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 836.

- Yaya Bocoum, F.; Kabore, C.P.; Barro, S.; Zerbo, R.; Tiendrebeogo, S.; Hanson, C.; Dumont, A.; Betran, A.P.; Bohren, M.A. Women’s and Health Providers’ Perceptions of Companionship during Labor and Childbirth: A Formative Study for the Implementation of WHO Companionship Model in Burkina Faso. Reprod. Health 2023, 20, 46.

- WHO. Companion of Choice during Labour and Childbirth for Improved Quality of Care; No. 4; Publications of the World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Klein, B.E.; Gouveia, H.G. USE Of NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL PAIN RELIEF METHODS In LABOR. Cogitare Enferm. 2022, 27, 481–496.

- Madden, K.L.; Turnbull, D.; Cyna, A.M.; Adelson, P.; Wilkinson, C. Pain Relief for Childbirth: The Preferences of Pregnant Women, Midwives and Obstetricians. Women Birth 2013, 26, 33–40.

- Pawale, M.; Salunkhe, J. Effectiveness of Back Massage on Pain Relief during First Stage of Labor in Primi Mothers Admitted at a Tertiary Care Center. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 5933.

- Silva Gallo, R.B.; Santana, L.S.; Jorge Ferreira, C.H.; Marcolin, A.C.; PoliNeto, O.B.; Duarte, G.; Quintana, S.M. Massage Reduced Severity of Pain during Labour: A Randomised Trial. J. Physiother. 2013, 59, 5933–5938.

- Eskandari, F.; Mousavi, P.; Valiani, M.; Ghanbari, S.; Iravani, M. A Comparison of the Effect of Swedish Massage with and without Chamomile Oil on Labor Outcomes and Maternal Satisfaction of the Childbirth Process: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2022, 27, 266.

- Smith, C.A.; Collins, C.T.; Levett, K.M.; Armour, M.; Dahlen, H.G.; Tan, A.L.; Mesgarpour, B. Acupuncture or Acupressure for Pain Management during Labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2, CD009232.

- Schlaeger, J.M.; Gabzdyl, E.M.; Bussell, J.L.; Takakura, N.; Yajima, H.; Takayama, M.; Wilkie, D.J. Acupuncture and Acupressure in Labor. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2017, 62, 12–28.

- Ashtarkan, M.J.; Akbari, S.A.A.; Nasiri, M.; Heshmat, R.; Eshraghi, N. Comparison of the Effect of Acupressure at SP6 and SP8 Points on Pain Intensity and Duration of the First Stage of Labor. Evid. Based Care J. 2021, 11, 25–34.

- Thuvarakan, K.; Zimmermann, H.; Mikkelsen, M.K.; Gazerani, P. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation As A Pain-Relieving Approach in Labor Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Neuromodulation 2020, 23, 732–746.

- Gibson, W.; Wand, B.M.; Meads, C.; Catley, M.J.; O’Connell, N.E. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) for Chronic Pain—An Overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 4, CD011890.

- Daniel, L.; Benson, J.; Hoover, S. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation for Pain Management for Women in Labor. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2021, 46, 76–81.

- Cluett, E.R.; Burns, E.; Cuthbert, A. Immersion in Water during Labour and Birth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD000111.

- Carlsson, T.; Ulfsdottir, H. Waterbirth in Low-Risk Pregnancy: An Exploration of Women’s Experiences. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 1221–1231.

- Cooper, M.; Warland, J. The Views and Perceptions of Water Immersion for Labor and Birth from Women Who Had Birthed in Australia but Had Not Used the Option. Eur. J. Midwifery 2022, 6, 54.

- Goswami, S.; Jelly, P.; Sharma, S.K.; Negi, R.; Sharma, R. The Effect of Heat Therapy on Pain Intensity, Duration of Labor during First Stage among Primiparous Women and Apgar Scores: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Midwifery 2022, 6, 66.

- Akbarzadeh, M.; Nematollahi, A.; Farahmand, M.; Amooee, S. The Effect of Two-Staged Warm Compress on the Pain Duration of First and Second Labor Stages and Apgar Score in Prim Gravida Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 7, 21–26.

- Akbarzadeh, M.; Vaziri, F.; Farahmand, M.; Masoudi, Z.; Amooee, S.; Zare, N. The Effect of Warm Compress Bistage Intervention on the Rate of Episiotomy, Perineal Trauma, and Post-partum Pain Intensity in Primiparous Women with Delayed Valsalva Maneuver Referring to the Selected Hospitals of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences in 2012–2013. Adv. Ski. Wound Care 2016, 29, 79–84.

- Dastjerd, F.; Erfanian Arghavanian, F.; Sazegarnia, A.; Akhlaghi, F.; Esmaily, H.; Kordi, M. Effect of Infrared Belt and Hot Water Bag on Labor Pain Intensity among Primiparous: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 405.

- Shirvani, M.A.; Ganji, Z. The Influence of Cold Pack on Labour Pain Relief and Birth Outcomes: A Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 2473–2480.

- Yildirim, E.; Inal, S. The Effect of Cold Application to the Sacral Area on Labor Pain and Labor Process: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Health Sci. J. Adıyaman Univ. 2022, 8, 96–105.

- Altınayak, S.Ö.; Özkan, H. The Effects of Conventional, Warm and Cold Acupressure on the Pain Perceptions and Beta-Endorphin Plasma Levels of Primiparous Women in Labor: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Explore 2022, 18, 545–550.

- Baljon, K.; Romli, M.H.; Ismail, A.H.; Khuan, L.; Chew, B.H. Effectiveness of Breathing Exercises, Foot Reflexology and Massage (BRM) on Maternal and Newborn Outcomes Among Primigravidae in Saudi Arabia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Womens Health 2022, 14, 279–295.

- Issac, A.; Nayak, S.G.; Priyadarshini, T.; Balakrishnan, D.; Halemani, K.; Mishra, P.; Indumathi, P.; Vijay, V.R.; Jacob, J.; Stephen, S. Effectiveness of Breathing Exercise on the Duration of Labour: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 04023.

- Yuksel, H.; Cayir, Y.; Kosan, Z.; Tastan, K. Effectiveness of Breathing Exercises during the Second Stage of Labor on Labor Pain and Duration: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 15, 456–461.

- Boaviagem, A.; Melo Junior, E.; Lubambo, L.; Sousa, P.; Aragão, C.; Albuquerque, S.; Lemos, A. The Effectiveness of Breathing Patterns to Control Maternal Anxiety during the First Period of Labor: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2016, 26, 30–35.

- Huang, J.; Zang, Y.; Ren, L.H.; Li, F.J.; Lu, H. A Review and Comparison of Common Maternal Positions during the Second-Stage of Labor. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 6, 460–467.

- Ondeck, M. Healthy Birth Practice #2: Walk, Move Around, and Change Positions Throughout Labor. J. Perinat. Educ. 2019, 28, 81–87.

- Borges, M.; Moura, R.; Oliveira, D.; Parente, M.; Mascarenhas, T.; Natal, R. Effect of the Birthing Position on Its Evolution from a Biomechanical Point of View. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 200, 105921.

- Abdul-Sattar Khudhur Ali, S.; Mirkhan Ahmed, H. Effect of Change in Position and Back Massage on Pain Perception during First Stage of Labor. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2018, 19, 288–294.

- Gür, E.Y.; Apay, S.E. The Effect of Cognitive Behavioral Techniques Using Virtual Reality on Birth Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Midwifery 2020, 91, 102856.

- Khojasteh, F.; Afrashte, M.; Khayat, S.; Navidian, A. Effect of Cognitive–Behavioral Training on Fear of Childbirth and Sleep Quality of Pregnant Adolescent Slum Dwellers. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 11, 311.

- Ehde, D.M.; Dillworth, T.M.; Turner, J.A. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Individuals with Chronic Pain Efficacy, Innovations, and Directions for Research. Am. Psychol. 2014, 69, 153–166.

- The Efficacy of Prenatal Yoga on Labor Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37023315/ (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Jahdi, F.; Sheikhan, F.; Haghani, H.; Sharifi, B.; Ghaseminejad, A.; Khodarahmian, M.; Rouhana, N. Yoga during Pregnancy: The Effects on Labor Pain and Delivery Outcomes (A Randomized Controlled Trial). Complement Ther. Clin. Pract. 2017, 27, 1–4.

- Massov, L. Giving Birth on a Beach Women’s Experiences of Using Virtual Reality in Labour A Pragmatic Mixed Methods Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, Open Access Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, 2021.

- Musters, A.; Vandevenne, A.S.; Franx, A.; Wassen, M.M.L.H. Virtual Reality Experience during Labour (VIREL); a Qualitative Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 283.

- Baradwan, S.; Khadawardi, K.; Badghish, E.; Alkhamis, W.H.; Dahi, A.A.; Abdallah, K.M.; Kamel, M.; Sayd, Z.S.; Mohamed, M.A.; Ali, H.M.; et al. The Impact of Virtual Reality on Pain Management during Normal Labor: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2022, 32, 100720.

- Xu, N.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Jing, Y.; Gu, P. The Effects of Virtual Reality in Maternal Delivery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Serious Games 2022, 10, e36695.

- Timmerman, H.; van Boekel, R.L.M.; van de Linde, L.S.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Vissers, K.C.P.; van der Wal, S.E.I.; Steegers, M.A.H. The Effect of Preferred Music versus Disliked Music on Pain Thresholds in Healthy Volunteers. An Observational Study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280036.

- Estrella-Juarez, F.; Requena-Mullor, M.; Garcia-Gonzalez, J.; Lopez-Villen, A.; Alarcon-Rodriguez, R. Effect of Virtual Reality and Music Therapy on the Physiologic Parameters of Pregnant Women and Fetuses and on Anxiety Levels: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2023, 68, 35–43.

- Chehreh, R.; Tavan, H.; Karamelahi, Z. The Effect of Music Therapy on Labor Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Douleurs Évaluation Diagn. Trait. 2023, 24, 110–117.

- García González, J.; Ventura Miranda, M.I.; Requena Mullor, M.; Parron Carreño, T.; Alarcón Rodriguez, R. Effects of Prenatal Music Stimulation on State/Trait Anxiety in Full-Term Pregnancy and Its Influence on Childbirth: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018, 31, 1058–1065.

- Ireland, L.D.; Allen, R.H. Pain Management for Gynecologic Procedures in the Office. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2016, 71, 89–98.

- Amiri, P.; Mirghafourvand, M.; Esmaeilpour, K.; Kamalifard, M.; Ivanbagha, R. The Effect of Distraction Techniques on Pain and Stress during Labor: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 534.

- Melillo, A.; Maiorano, P.; Rachedi, S.; Caggianese, G.; Gragnano, E.; Gallo, L.; De Pietro, G.; Guida, M.; Giordano, A.; Chirico, A. Labor Analgesia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Non-Pharmacological Complementary and Alternative Approaches to Pain during First Stage of Labor. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2022, 32, 61–89.

- Smith, C.A.; Shewamene, Z.; Galbally, M.; Schmied, V.; Dahlen, H. The Effect of Complementary Medicines and Therapies on Maternal Anxiety and Depression in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 245, 428–439.

- Hosseni, S.F.; Pilevarzadeh, M.; Vazirinasab, H. Non-Pharmacological Strategies on Pain Relief During Labor. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia 2016, 13, 701–706.

- Frawley, J.; Adams, J.; Sibbritt, D.; Steel, A.; Broom, A.; Gallois, C. Prevalence and Determinants of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use during Pregnancy: Results from a Nationally Representative Sample of Australian Pregnant Women. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013, 53, 347–352.

- Fjær, E.L.; Landet, E.R.; McNamara, C.L.; Eikemo, T.A. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) in Europe. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 108.

- Madden, K.; Middleton, P.; Cyna, A.M.; Matthewson, M.; Jones, L. Hypnosis for Pain Management during Labour and Childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD009356.

- Cyna, A.M.; Crowther, C.A.; Robinson, J.S.; Andrew, M.I.; Antoniou, G.; Baghurst, P. Hypnosis Antenatal Training for Childbirth: A Randomised Controlled Trial. BJOG 2013, 120, 1248–1259.

- Downe, S.; Finlayson, K.; Melvin, C.; Spiby, H.; Ali, S.; Diggle, P.; Gyte, G.; Hinder, S.; Miller, V.; Slade, P.; et al. Self-Hypnosis for Intrapartum Pain Management in Pregnant Nulliparous Women: A Randomised Controlled Trial of Clinical Effectiveness. BJOG 2015, 122, 1226–1234.

- McLaren, H.; Patmisari, E.; Hamiduzzaman, M.; Jones, M.; Taylor, R. Respect for Religiosity: Review of Faith Integration in Health and Wellbeing Interventions with Muslim Minorities. Religions 2021, 12, 692.

- Desmawati, D.; Kongsuwan, W.; Chatchawet, W. Effect of Nursing Intervention Integrating an Islamic Praying Program on Labor Pain and Pain Behaviors in Primiparous Muslim Women. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2019, 24, 220–226.

- Kocak, M.Y.; Göçen, N.N.; Akin, B. The Effect of Listening to the Recitation of the Surah Al-Inshirah on Labor Pain, Anxiety and Comfort in Muslim Women: A Randomized Controlled Study. J. Relig. Health 2022, 61, 2945–2959.

- Abdolahian, S.; Ghavi, F.; Abdollahifard, S.; Sheikhan, F. Effect of Dance Labor on the Management of Active Phase Labor Pain & Clients’’Satisfaction: A Randomized Controlled Trial Study. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2014, 6, 219–226.

- Akin, B.; Saydam, B.K. The Effect of Labor Dance on Perceived Labor Pain, Birth Satisfaction, and Neonatal Outcomes. Explore 2020, 16, 310–317.

- Tabatabaeichehr, M.; Mortazavi, H. The Effectiveness of Aromatherapy in the Management of Labor Pain and Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2020, 30, 449–458.

- Tanvisut, R.; Traisrisilp, K.; Tongsong, T. Efficacy of Aromatherapy for Reducing Pain during Labor: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 297, 1145–1150.

- Hamdamian, S.; Nazarpour, S.; Simbar, M.; Hajian, S.; Mojab, F.; Talebi, A. Effects of Aromatherapy with Rosa Damascena on Nulliparous Women’’ ‘Pain and Anxiety of Labor during First Stage of Labor. J. Integr. Med. 2018, 16, 120–125.

- Traverzim, M.A.; Sobral, A.P.T.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; De Fátima Teixeira Silva, D.; Pavani, C.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A.; Horliana, A.C.R.T.; Gomes, A.O.; Bussadori, S.K.; Motta, L.J. The Effect of Photobiomodulation on Analgesia during Childbirth: A Controlled and Randomized Clinical Trial. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg. 2021, 39, 265–271.

- Traverzim, M.A.D.S.; Makabe, S.; Silva, D.F.T.; Pavani, C.; Bussadori, S.K.; Fernandes, K.S.P.; Motta, L.J. Effect of Led Photobiomodulation on Analgesia during Labor: Study Protocol for a Randomized Clinical Trial. Medicine 2018, 97, e11120.

- Akbaş, P.; Özkan Şat, S.; Yaman Sözbir, Ş. The Effect of Holistic Birth Support Strategies on Coping With Labor Pain, Birth Satisfaction, and Fear of Childbirth: A Randomized, Triple-Blind, Controlled Trial. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2022, 31, 1352–1361.

- Bohren, M.A.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; Sakala, C.; Fukuzawa, R.K.; Cuthbert, A. Continuous Support for Women during Childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD003766.

- Ip, W.Y.; Tang, C.S.K.; Goggins, W.B. An Educational Intervention to Improve Women’s Ability to Cope with Childbirth. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 2125–2135.

More

Information

Subjects:

Obstetrics & Gynaecology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.0K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

22 Jan 2024

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No