Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Imola Plangár | -- | 1835 | 2023-12-13 11:02:56 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 1835 | 2023-12-14 02:07:10 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

László, K.; Vörös, D.; Correia, P.; Fazekas, C.L.; Török, B.; Plangár, I.; Zelena, D. Vasopressin-Related Possible Therapies in Autism. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52679 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

László K, Vörös D, Correia P, Fazekas CL, Török B, Plangár I, et al. Vasopressin-Related Possible Therapies in Autism. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52679. Accessed February 07, 2026.

László, Kristóf, Dávid Vörös, Pedro Correia, Csilla Lea Fazekas, Bibiána Török, Imola Plangár, Dóra Zelena. "Vasopressin-Related Possible Therapies in Autism" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52679 (accessed February 07, 2026).

László, K., Vörös, D., Correia, P., Fazekas, C.L., Török, B., Plangár, I., & Zelena, D. (2023, December 13). Vasopressin-Related Possible Therapies in Autism. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52679

László, Kristóf, et al. "Vasopressin-Related Possible Therapies in Autism." Encyclopedia. Web. 13 December, 2023.

Copy Citation

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is rather common, presenting with prevalent early problems in social communication and accompanied by repetitive behavior. There is no cure for ASD, and there is currently no medication to treat it. The medications are prescribed mainly to treat self-injury, inability to focus, anxiety and depression (SSRIs), aggression (alpha-2 adrenergic agonist, Clonidine) and hyperactivity (dopamine and noradrenaline stimulant methylphenidate, Ritalin). Strategies to treat the core symptoms of ASD are directed to correct synaptic dysfunctions, abnormalities in central VP, OT and serotonin neurotransmission, and neuroinflammation.

autism spectrum disorder

vasopressin

social behavior

stereotype behavior

1. Available Therapies with Possible Vasopressinergic Contribution

Among the most prescribed medications for autism [1], the following VP interactions can be supposed:

From the second-generation antipsychotics used for the treatment of irritability, cariprazine is promising and their serotoninergic effect suggest a possible VPergic contribution [2].

For the improvement of mood, as well as to reduce the frequency and intensity of repetitive behaviors and improve eye contact, SSRIs are often used. In this regard, VP–serotonin interaction might contribute to the possible effectiveness of aggression treatment using SSRIs [3].

As regards methylphenidate (Ritalin), a dopamine (DA) reuptake inhibitor, it is used as a stimulant for the treatment of hyperactivity (paradoxically) and lack of attention in ASD. It was shown that it may influence the VP system [4] and it acts—at least partly—via the V1a receptor [5].

Alpha2-agonist (e.g., Clonidine) may be used for ASD-related hyperactivity, attention deficit, and aggression, and may interact with VP on the cardiovascular function. Indeed, i.c.v. Clonidine administration-induced pressor response was prevented by i.c.v. V1 antagonist administration in rats [6]. Interestingly, in humans, Clonidine administration decreased plasma VP levels [7]. In horses, no interaction was found between Clonidine and VP on HPA axis [8]; however, in rats, Clonidine reduced the firing of SON VPergic cells, further supporting an interaction at the level of water balance [9].

As for applied behavior analysis (ABA), in a backtranslation study using ASD model mice, this intervention normalized VP and V1a expression in several brain areas, including MeA [10].

Even transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation elevated VP levels in connection with an improvement of ASD symptoms [11].

Although experts do not recommend any specific diets for children (not even gluten- or casein-free), some probiotics might improve gastrointestinal symptoms [12]. As a possible link to VP, in prairie voles, Limosilactobacillus reuteri administration resulted in lower anxiety, but also lower social affiliation in female but not male individuals, with a decrease in PVN V1a expression [13].

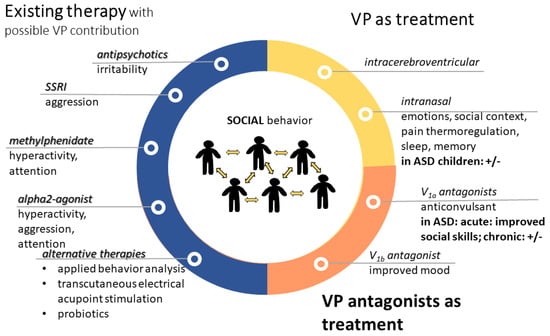

For a summary, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Treatment options in autism with contribution of vasopressin. VP might contribute to the effectiveness of presently available therapies (blue). However, VP alone (yellow) or its antagonists (orange) can be used for therapy. Most of the treatments aim to improve social skills; however, sometimes the results are questionable (+/−). Abbreviations: ASD: autism spectrum disorder; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; V1a: vasopressin 1a receptor; VP: vasopressin.

2. Influencing the Vasopressinergic System in Autism-Related Problems

Besides the aforementioned indirect effects, the direct influence on the VP pathway might have therapeutic potential on its own.

As VP does not cross the blood–brain barrier [14], for influencing the central VPergic system, i.c.v. or i.n. application is preferable.

In a rat VPA model, acute i.c.v. VP administration prevented social-interaction-induced brain activation based on blood oxygenation level (BOLD) signal in fMRI [15].

2.1. Intranasal Vasopressin Application

In rats, i.n. VP treatment (from PND 21 for 3 weeks) improved maternal VPA injection-induced (E12.5) social deficit, elevated the serum VP level and corrected expression changes related to synaptic and axon dysplasia and oligodendrocyte development in the PFC [16] and amygdala [17].

In male, but not female, marmosets, i.n. VP administration reduced food sharing with increased aggressive vocalization [18]. Accordingly, in monogamous male prairie voles [19], as well as in the coppery titi monkey (Callicebus cupreus) [20], a similar treatment reduced partner preference. These preclinical results did not suggest a possible positive effect on ASD symptoms.

However, when VP was administered i.n. for 4 weeks in ASD children aged 6–13 years in a phase 2 randomized clinical trial, improved social responsiveness and social abilities with decreased anxiety and limited repetitive behavior were reported [21]. The response was the strongest in high-plasma VP patients, and depended on the expression pattern of the V1a and OTR receptors. The latter might explain the controversially decreased anxiety, as V1b receptors were more involved in this stress-related disorder. In contrast, a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, between-subjects design on 125 undergraduate students (with 41 placebo, 30 females in each), using i.n. VP administration, did not find any effect on social outcomes [22]. In support, i.n. VP administration in rats failed to influence social recognition [23], despite previous effectiveness of the direct olfactory bulb manipulation [24]. Moreover, in healthy male volunteers, i.n. VP administration decreased goal-directed top-down attention control to social salient stimuli with an increase in bottom-up social attentional processing [25]. This effect was similar to OT administration and accompanied by an anxiolytic effect as well. In another study on face processing, a single low-dose i.n. VP (20 IU) administration to men decreased social assessments with a most pronounced effect in V1a risk allele carrier subjects [26]. This suggest that via i.n. application, significant amounts of VP might not reach behaviorally relevant areas in the brain described previously as targets for the central administration of the peptide [23].

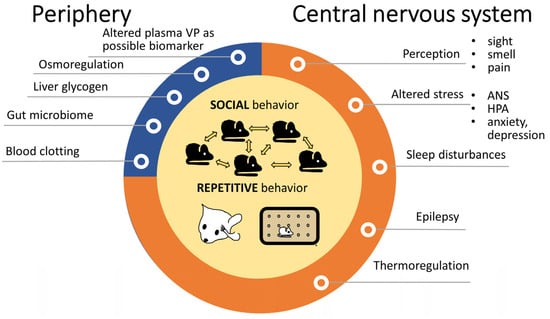

For other ASD-related alterations, where possible VP contribution was suggested (Figure 2), the following treatment effects were found:

Figure 2. Alterations in autism spectrum disorders with possible contribution of vasopressin. The observations were mainly in animals. Both social problems and repetitive behaviors—depicted in the middle—are core features of autism spectrum disorders and VP is obviously implicated in them. Peripheral VP functions (blue) might be only indirectly linked to autism, while other central VP effects (orange) might have a more important, although not yet fully clarified role. Abbreviations: ANS: autonomous nervous system; HPA: hypothalamic pituitary adrenocortical axis, VP: vasopressin.

The activity of brain regions implicated in emotion processing was altered by i.n. VP treatment [27]. In this regard, in humans, i.n. VP regulated the processing of infant cry sounds with emotional contextual information in fathers [28]. In male volunteers, i.n. VP administration increased approaching ratings to some faces, together with increased processing suggested by higher N1 amplitude on the electroencephalograph; however, this effect was highly context-dependent [29]. Another study using fMRI in healthy male subjects reported reduced amygdalar activation to emotional faces after i.n. VP administration [30]. In contrast, another study reported enhanced neural pattern in the right amygdala to social–emotional stimuli observed via MRI [31].

As mentioned before, i.n. VP administration was also able to reduce pain in relation to postoperative orthopedic surgery [32].

Regarding its thermoregulatory role, i.n. VP (more specifically desmopressin, a V2 receptor-selective agonist) reduced persisting coldness after brain injury in six patients [33].

In contrast, i.n. VP administration exacerbated physiological ANS parameters in combat veterans [34].

In healthy, elderly subjects, i.n. VP promoted sleep time and improved sleep architecture [35], reinforcing the potential beneficial effect of VP in ASD treatment. However, it was ineffective as regards verbal memory function [36].

2.2. Vasopressin Antagonist Treatment

In recent years, vasopressin receptor antagonists have been in the spotlight of drug discovery, especially V1a selective molecules [37]. Publishing Balovaptan as a possible treatment for ASD greatly increased the interest in CNS-acting vasopressin antagonists. Although clinical trials were unsuccessful in many cases, there is still potential in the VP antagonists as shown by several currently ongoing clinical studies.

The main focus is on V1a receptor antagonists. In this context, SRX246, a V1a receptor antagonist, blocked the effect of i.n. VP administration-induced reduced amygdalar activation to angry faces [30]. Moreover, in 2017, a multicenter double-blinded crossover study found that single-dose intravenous (i.v.) infusion of RG7713, a highly selective V1a antagonist in adult males with high-functioning ASD, resulted in a subtle but statistically significant improvement in social communications and social sensitivity [38]. As a follow up, the VP Antagonist to Improve Social Communication in Autism (VANILLA), a double-blinded placebo controlled clinical trial, examined 223 adult men with high-functioning ASD using another selective V1a receptor antagonist, RG7714 (commercially known as Balovaptan) for 3 months [39]. The treatment was well tolerated and resulted in improvement in communication and socialization scores, though not in all aspects of the ASD spectrum (e.g., social responsiveness was not improved). Despite effectiveness during the phase 2 trial [40], in subsequent phase 3 trials in high-functioning children (5–17-year) [41] and adults (above 18-year) [42], the 6-month Balovaptan treatment was ineffective as regards social communication.

Other selective V1a receptor antagonists (like the orally active Relcovaptan) might be effective as regards comorbid epilepsy [14]. On the other hand, for many years, V1b receptor antagonists were developed to treat mood disorders. Despite previous ineffectiveness in major depression [43], V1b receptor antagonists might be effective in subpopulations [44][45] and are therefore still under development (e.g., THY1773 [46], TS-121 [47], ABT-436 [48]). We cannot ignore V2 receptors either, as Tolvaptan, a V2 antagonist was implicated in the treatment of tuberous sclerosis, a genetic ASD, in a case report [49] (Table 1).

Table 1. Animal models of autism with possible contribution of vasopressin.

| Model | Major Problems | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Name/Implicated Molecule | |||

| Genetic models | KO | OTR | soc. | [50] |

| CNTNAP2 | soc., com. | [51] | ||

| MAGEL2 | soc. | [52] | ||

| OPRM1 | soc. | [53][54] | ||

| Klf7 | soc., rep. | [55] | ||

| Fragile X | FMR1 | soc., rep., motor problem, mood | [56] | |

| Rett syndrome | MECP2 | soc., com. | [57] | |

| Tuberous sclerosis | TSC1, TSC2 | soc., rep.; cerebellum; V2 antagonist | [49] | |

| Indirect evidence | NLGN mutations | soc., rest., com. | [58][59] | |

| TSHZ3 KO | soc., rep., narrowness of the field of interest | [60][61] | ||

| GLUT3 KO | soc., rep., com., memory problems | [62][63] | ||

| parvalbumin KO | soc., rep., com. | [64][65] | ||

| GAP43 | soc., resistance to change | [66][67] | ||

| SERT variants | soc., rep. | [68][69][70][71] | ||

| Environmental models | Drugs | VPA | soc., rep., com. | [17][72] |

| Maternal infection and inflammation | poly I:C | soc., rep. | [73][74] | |

| LPS | soc. | [75][76] | ||

| MIA | soc. | [74] | ||

Abbreviations: CNTNAP2: Contactin Associated Protein 2; Com: communication problems; Fragile Mental Retardation 1 locus (FMR1); GAP43: synaptic growth-associated protein-43; GLUT3: neuronal glucose transporter isoform 3; klf7: Krüppel-like factor 7; KO: knockout; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; MAGEL2: Melanoma Antigen Gene Family Member L2; MIA: maternal immune activation; methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MECP2), NLGN: neuroligin; rep: repetitive behavior; poly I:C: polyriboinosinic: polyribocytidylic acid; OPRM1: μ opioid receptor; soc: social problems; TSC: tuberous sclerosis complex; TSHZ3: a zinc-finger transcription factor; VPA: valproate [77].

2.3. Oxytocin Treatment

As VP might bind to OTRs (see earlier), it is important to note that several animal trials of OT treatment suggested beneficial effects. In children, even a single intranasal OT administration increased the nonverbal information-based judgments [78]. Despite mixed results, a recent meta-analysis found moderate evidence that a 6-week OT treatment might improve the reduced interest and repetitive behavior of ASD children and the effect lasted for at least 6 months [79].

2.4. Contradiction

There is an apparent contradiction between the effectiveness of VP as well as its antagonist. A possible explanation can be the age of the participants as well as the method used for drug administration (i.n. for children, other peripheral routes for adults), thereby targeting central or peripheral receptors. Moreover, although VP may stimulate all receptors including OTRs, its effectiveness can be different on them, while antagonists are highly selective, which might shift balance between the VP receptor actions.

References

- Jacob, D. Types of Medication for Autism. 2022. Available online: https://www.rxlist.com/types_of_medication_for_autism/drugs-condition.htm (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Yeung, P.P.; Johnson, K.A.; Riesenberg, R.; Orejudos, A.; Riccobene, T.; Kalluri, H.V.; Malik, P.R.; Varughese, S.; Findling, R.L. Cariprazine in Pediatric Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Results of a Pharmacokinetic, Safety and Tolerability Study. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2023, 33, 232–242.

- Landry, M.; Frasier, M.; Chen, Z.; Van De Kar, L.D.; Zhang, Y.; Garcia, F.; Battaglia, G. Fluoxetine treatment of prepubescent rats produces a selective functional reduction in the 5-HT2A receptor-mediated stimulation of oxytocin. Synapse 2005, 58, 102–109.

- Appenrodt, E.; Bojanowska, E.; Janus, J.; Stempniak, B.; Guzek, J.W.; Schwarzberg, H. Effects of methylphenidate on oxytocin and vasopressin levels in pinealectomized rats during light-dark cycle. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1997, 58, 415–419.

- Appenrodt, E.; Schwarzberg, H. Methylphenidate-induced motor activity in rats: Modulation by melatonin and vasopressin. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2003, 75, 67–73.

- Nakamura, S.; Kawasaki, H.; Takasaki, K. Intracerebroventricular treatment with vasopressin V1-receptor antagonist inhibits centrally-mediated pressor response to clonidine in conscious rats. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1993, 63, 447–453.

- Brown, G.M.; Mazurek, M.; Allen, D.; Szechtman, B.; Cleghorn, J.M. Dose-response profiles of plasma growth hormone and vasopressin after clonidine challenge in man. Psychiatry Res. 1990, 31, 311–320.

- Alexander, S.L.; Irvine, C.H. The effect of the alpha-2-adrenergic agonist, clonidine, on secretion patterns and rates of adrenocorticotropic hormone and its secretagogues in the horse. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2000, 12, 874–880.

- Bailey, A.R.; Clarke, G.; Wakerley, J.B. Inhibition of supraoptic vasopressin neurones following systemic clonidine. Neuropharmacology 1994, 33, 211–214.

- Pujol, C.N.; Pellissier, L.P.; Clement, C.; Becker, J.A.J.; Le Merrer, J. Back-translating behavioral intervention for autism spectrum disorders to mice with blunted reward restores social abilities. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 197.

- Zhang, R.; Jia, M.X.; Zhang, J.S.; Xu, X.J.; Shou, X.J.; Zhang, X.T.; Li, L.; Li, N.; Han, S.P.; Han, J.S. Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation in children with autism and its impact on plasma levels of arginine-vasopressin and oxytocin: A prospective single-blinded controlled study. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 1136–1146.

- Arnold, L.E.; Luna, R.A.; Williams, K.; Chan, J.; Parker, R.A.; Wu, Q.; Hollway, J.A.; Jeffs, A.; Lu, F.; Coury, D.L.; et al. Probiotics for Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Quality of Life in Autism: A Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 659–669.

- Donovan, M.; Mackey, C.S.; Lynch, M.D.J.; Platt, G.N.; Brown, A.N.; Washburn, B.K.; Trickey, D.J.; Curtis, J.T.; Liu, Y.; Charles, T.C.; et al. Limosilactobacillus reuteri administration alters the gut-brain-behavior axis in a sex-dependent manner in socially monogamous prairie voles. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1015666.

- Dobolyi, A.; Kekesi, K.A.; Juhasz, G.; Szekely, A.D.; Lovas, G.; Kovacs, Z. Receptors of peptides as therapeutic targets in epilepsy research. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 764–787.

- Felix-Ortiz, A.C.; Febo, M. Gestational valproate alters BOLD activation in response to complex social and primary sensory stimuli. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37313.

- Zhou, B.; Yan, X.; Yang, L.; Zheng, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; et al. Effects of arginine vasopressin on the transcriptome of prefrontal cortex in autistic rat model. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2022, 26, 5493–5505.

- Zhou, B.; Zheng, X.; Chen, Y.; Yan, X.; Peng, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, L.; Wen, M. The Changes of Amygdala Transcriptome in Autism Rat Model After Arginine Vasopressin Treatment. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 838942.

- Taylor, J.H.; Intorre, A.A.; French, J.A. Vasopressin and Oxytocin Reduce Food Sharing Behavior in Male, but Not Female Marmosets in Family Groups. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 181.

- Simmons, T.C.; Balland, J.F.; Dhauna, J.; Yang, S.Y.; Traina, J.L.; Vazquez, J.; Bales, K.L. Early Intranasal Vasopressin Administration Impairs Partner Preference in Adult Male Prairie Voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 145.

- Jarcho, M.R.; Mendoza, S.P.; Mason, W.A.; Yang, X.; Bales, K.L. Intranasal vasopressin affects pair bonding and peripheral gene expression in male Callicebus cupreus. Genes. Brain Behav. 2011, 10, 375–383.

- Parker, K.J.; Oztan, O.; Libove, R.A.; Mohsin, N.; Karhson, D.S.; Sumiyoshi, R.D.; Summers, J.E.; Hinman, K.E.; Motonaga, K.S.; Phillips, J.M.; et al. A randomized placebo-controlled pilot trial shows that intranasal vasopressin improves social deficits in children with autism. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaau7356.

- Tabak, B.A.; Teed, A.R.; Castle, E.; Dutcher, J.M.; Meyer, M.L.; Bryan, R.; Irwin, M.R.; Lieberman, M.D.; Eisenberger, N.I. Null results of oxytocin and vasopressin administration across a range of social cognitive and behavioral paradigms: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 107, 124–132.

- Ludwig, M.; Tobin, V.A.; Callahan, M.F.; Papadaki, E.; Becker, A.; Engelmann, M.; Leng, G. Intranasal application of vasopressin fails to elicit changes in brain immediate early gene expression, neural activity and behavioural performance of rats. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2013, 25, 655–667.

- Tobin, V.A.; Hashimoto, H.; Wacker, D.W.; Takayanagi, Y.; Langnaese, K.; Caquineau, C.; Noack, J.; Landgraf, R.; Onaka, T.; Leng, G.; et al. An intrinsic vasopressin system in the olfactory bulb is involved in social recognition. Nature 2010, 464, 413–417.

- Zhuang, Q.; Zheng, X.; Becker, B.; Lei, W.; Xu, X.; Kendrick, K.M. Intranasal vasopressin like oxytocin increases social attention by influencing top-down control, but additionally enhances bottom-up control. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 133, 105412.

- Price, D.; Burris, D.; Cloutier, A.; Thompson, C.B.; Rilling, J.K.; Thompson, R.R. Dose-Dependent and Lasting Influences of Intranasal Vasopressin on Face Processing in Men. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 220.

- Frye, R.E. Social Skills Deficits in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Potential Biological Origins and Progress in Developing Therapeutic Agents. CNS Drugs 2018, 32, 713–734.

- Thijssen, S.; Van ‘t Veer, A.E.; Witteman, J.; Meijer, W.M.; Van, I.M.H.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J. Effects of vasopressin on neural processing of infant crying in expectant fathers. Horm. Behav. 2018, 103, 19–27.

- Wu, X.; Xu, P.; Luo, Y.J.; Feng, C. Differential Effects of Intranasal Vasopressin on the Processing of Adult and Infant Cues: An ERP Study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 329.

- Lee, R.J.; Coccaro, E.F.; Cremers, H.; McCarron, R.; Lu, S.F.; Brownstein, M.J.; Simon, N.G. A novel V1a receptor antagonist blocks vasopressin-induced changes in the CNS response to emotional stimuli: An fMRI study. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 100.

- Brunnlieb, C.; Munte, T.F.; Tempelmann, C.; Heldmann, M. Vasopressin modulates neural responses related to emotional stimuli in the right amygdala. Brain Res. 2013, 1499, 29–42.

- Yang, F.J.; Ma, L.; Yang, J.; Zhu, Z.L.; Wang, C.H. Intranasal Vasopressin Relieves Orthopedic Pain After Surgery. Pain. Manag. Nurs. 2019, 20, 126–132.

- Silver, J.M.; Anderson, K. Vasopressin treats the persistent feeling of coldness after brain injury. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1999, 11, 248–252.

- Pitman, R.K.; Orr, S.P.; Lasko, N.B. Effects of intranasal vasopressin and oxytocin on physiologic responding during personal combat imagery in Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1993, 48, 107–117.

- Perras, B.; Pannenborg, H.; Marshall, L.; Pietrowsky, R.; Born, J.; Lorenz Fehm, H. Beneficial treatment of age-related sleep disturbances with prolonged intranasal vasopressin. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1999, 19, 28–36.

- Perras, B.; Droste, C.; Born, J.; Fehm, H.L.; Pietrowsky, R. Verbal memory after three months of intranasal vasopressin in healthy old humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1997, 22, 387–396.

- Baska, F.; Bozo, E.; Patocs, T. Vasopressin receptor antagonists: A patent summary (2018–2022). Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2023, 33, 385–395.

- Umbricht, D.; Del Valle Rubido, M.; Hollander, E.; McCracken, J.T.; Shic, F.; Scahill, L.; Noeldeke, J.; Boak, L.; Khwaja, O.; Squassante, L.; et al. A Single Dose, Randomized, Controlled Proof-of-Mechanism Study of a Novel Vasopressin 1a Receptor Antagonist (RG7713) in High-Functioning Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 1914–1923.

- Bolognani, F.; Rubido, M.d.V.; Squassante, L.; Wandel, C.; Derks, M.; Murtagh, L.; Sevigny, J.; Khwaja, O.; Umbricht, D.; Fontoura, P. A phase 2 clinical trial of a vasopressin V1a receptor antagonist shows improved adaptive behaviors in men with autism spectrum disorder. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaat7838.

- Schnider, P.; Bissantz, C.; Bruns, A.; Dolente, C.; Goetschi, E.; Jakob-Roetne, R.; Kunnecke, B.; Mueggler, T.; Muster, W.; Parrott, N.; et al. Discovery of Balovaptan, a Vasopressin 1a Receptor Antagonist for the Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 1511–1525.

- Hollander, E.; Jacob, S.; Jou, R.; McNamara, N.; Sikich, L.; Tobe, R.; Smith, J.; Sanders, K.; Squassante, L.; Murtagh, L.; et al. Balovaptan vs. Placebo for Social Communication in Childhood Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 760–769.

- Jacob, S.; Veenstra-VanderWeele, J.; Murphy, D.; McCracken, J.; Smith, J.; Sanders, K.; Meyenberg, C.; Wiese, T.; Deol-Bhullar, G.; Wandel, C.; et al. Efficacy and safety of balovaptan for socialisation and communication difficulties in autistic adults in North America and Europe: A phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 199–210.

- Griebel, G.; Beeske, S.; Stahl, S.M. The vasopressin V(1b) receptor antagonist SSR149415 in the treatment of major depressive and generalized anxiety disorders: Results from 4 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 73, 1403–1411.

- Ding, Y.; Wei, Z.; Yan, H.; Guo, W. Efficacy of Treatments Targeting Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Systems for Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 732157.

- Chaki, S. Vasopressin V1B Receptor Antagonists as Potential Antidepressants. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 24, 450–463.

- Inatani, S.; Mizuno-Yasuhira, A.; Kamiya, M.; Nishino, I.; Sabia, H.D.; Endo, H. Prediction of a clinically effective dose of THY1773, a novel V(1B) receptor antagonist, based on preclinical data. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2021, 42, 204–217.

- Kamiya, M.; Sabia, H.D.; Marella, J.; Fava, M.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Umeuchi, H.; Iijima, M.; Chaki, S.; Nishino, I. Efficacy and safety of TS-121, a novel vasopressin V(1B) receptor antagonist, as adjunctive treatment for patients with major depressive disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 128, 43–51.

- Katz, D.A.; Locke, C.; Greco, N.; Liu, W.; Tracy, K.A. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and depression symptom effects of an arginine vasopressin type 1B receptor antagonist in a one-week randomized Phase 1b trial. Brain Behav. 2017, 7, e00628.

- Guerra-Torres, X.E. A Case Report of Tuberous Sclerosis and Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease in the Era of Tolvaptan. Curr. Rev. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. 2023, 18, 284–290.

- Sala, M.; Braida, D.; Lentini, D.; Busnelli, M.; Bulgheroni, E.; Capurro, V.; Finardi, A.; Donzelli, A.; Pattini, L.; Rubino, T.; et al. Pharmacologic rescue of impaired cognitive flexibility, social deficits, increased aggression, and seizure susceptibility in oxytocin receptor null mice: A neurobehavioral model of autism. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 69, 875–882.

- Penagarikano, O.; Lazaro, M.T.; Lu, X.H.; Gordon, A.; Dong, H.; Lam, H.A.; Peles, E.; Maidment, N.T.; Murphy, N.P.; Yang, X.W.; et al. Exogenous and evoked oxytocin restores social behavior in the Cntnap2 mouse model of autism. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 271ra8.

- Borie, A.M.; Theofanopoulou, C.; Andari, E. The promiscuity of the oxytocin-vasopressin systems and their involvement in autism spectrum disorder. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2021, 182, 121–140.

- Tanaka, H.; Nishina, K.; Shou, Q.; Takahashi, H.; Sakagami, M.; Matsuda, T.; Inoue-Murayama, M.; Takagishi, H. Association between arginine vasopressin receptor 1A (AVPR1A) polymorphism and inequity aversion. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2023, 290, 20230378.

- Garbugino, L.; Centofante, E.; D’Amato, F.R. Early Social Enrichment Improves Social Motivation and Skills in a Monogenic Mouse Model of Autism, the Oprm1 (-/-) Mouse. Neural Plast. 2016, 2016, 5346161.

- Tian, H.; Jiao, Y.; Guo, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, C.; Chen, X.; Tian, W. Kruppel-like factor 7 deficiency causes autistic-like behavior in mice via regulating Clock gene. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 166.

- Francis, S.M.; Sagar, A.; Levin-Decanini, T.; Liu, W.; Carter, C.S.; Jacob, S. Oxytocin and vasopressin systems in genetic syndromes and neurodevelopmental disorders. Brain Res. 2014, 1580, 199–218.

- Martinez-Rodriguez, E.; Martin-Sanchez, A.; Kul, E.; Bose, A.; Martinez-Martinez, F.J.; Stork, O.; Martinez-Garcia, F.; Lanuza, E.; Santos, M.; Agustin-Pavon, C. Male-specific features are reduced in Mecp2-null mice: Analyses of vasopressinergic innervation, pheromone production and social behaviour. Brain Struct. Funct. 2020, 225, 2219–2238.

- Calahorro, F.; Alejandre, E.; Ruiz-Rubio, M. Osmotic avoidance in Caenorhabditis elegans: Synaptic function of two genes, orthologues of human NRXN1 and NLGN1, as candidates for autism. J. Vis. Exp. 2009, 34, e1616.

- Jamain, S.; Radyushkin, K.; Hammerschmidt, K.; Granon, S.; Boretius, S.; Varoqueaux, F.; Ramanantsoa, N.; Gallego, J.; Ronnenberg, A.; Winter, D.; et al. Reduced social interaction and ultrasonic communication in a mouse model of monogenic heritable autism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1710–1715.

- Roubertoux, P.L.; Tordjman, S.; Caubit, X.; di Cristopharo, J.; Ghata, A.; Fasano, L.; Kerkerian-Le Goff, L.; Gubellini, P.; Carlier, M. Construct Validity and Cross Validity of a Test Battery Modeling Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Mice. Behav. Genet. 2020, 50, 26–40.

- Sanchez-Martin, I.; Magalhaes, P.; Ranjzad, P.; Fatmi, A.; Richard, F.; Manh, T.P.V.; Saurin, A.J.; Feuillet, G.; Denis, C.; Woolf, A.S.; et al. Haploinsufficiency of the mouse Tshz3 gene leads to kidney defects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 31, 1921–1945.

- Vannucci, S.J.; Maher, F.; Koehler, E.; Simpson, I.A. Altered expression of GLUT-1 and GLUT-3 glucose transporters in neurohypophysis of water-deprived or diabetic rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1994, 267, E605–E611.

- Zhao, Y.; Fung, C.; Shin, D.; Shin, B.C.; Thamotharan, S.; Sankar, R.; Ehninger, D.; Silva, A.; Devaskar, S.U. Neuronal glucose transporter isoform 3 deficient mice demonstrate features of autism spectrum disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 15, 286–299.

- Wohr, M.; Orduz, D.; Gregory, P.; Moreno, H.; Khan, U.; Vorckel, K.J.; Wolfer, D.P.; Welzl, H.; Gall, D.; Schiffmann, S.N.; et al. Lack of parvalbumin in mice leads to behavioral deficits relevant to all human autism core symptoms and related neural morphofunctional abnormalities. Transl. Psychiatry 2015, 5, e525.

- Hammock, E.A.; Levitt, P. Modulation of parvalbumin interneuron number by developmentally transient neocortical vasopressin receptor 1a (V1aR). Neuroscience 2012, 222, 20–28.

- Feng, Z.; Ou, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wu, G.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qi, S. Functional ectopic neural lobe increases GAP-43 expression via PI3K/AKT pathways to alleviate central diabetes insipidus after pituitary stalk lesion in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 673, 1–6.

- Zaccaria, K.J.; Lagace, D.C.; Eisch, A.J.; McCasland, J.S. Resistance to change and vulnerability to stress: Autistic-like features of GAP43-deficient mice. Genes. Brain Behav. 2010, 9, 985–996.

- Kyzar, E.J.; Pham, M.; Roth, A.; Cachat, J.; Green, J.; Gaikwad, S.; Kalueff, A.V. Alterations in grooming activity and syntax in heterozygous SERT and BDNF knockout mice: The utility of behavior-recognition tools to characterize mutant mouse phenotypes. Brain Res. Bull. 2012, 89, 168–176.

- Veenstra-VanderWeele, J.; Muller, C.L.; Iwamoto, H.; Sauer, J.E.; Owens, W.A.; Shah, C.R.; Cohen, J.; Mannangatti, P.; Jessen, T.; Thompson, B.J.; et al. Autism gene variant causes hyperserotonemia, serotonin receptor hypersensitivity, social impairment and repetitive behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 5469–5474.

- Pompili, M.; Serafini, G.; Innamorati, M.; Moller-Leimkuhler, A.M.; Giupponi, G.; Girardi, P.; Tatarelli, R.; Lester, D. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and serotonin abnormalities: A selective overview for the implications of suicide prevention. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2010, 260, 583–600.

- Morrison, T.R.; Melloni, R.H., Jr. The role of serotonin, vasopressin, and serotonin/vasopressin interactions in aggressive behavior. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 189–228.

- Wu, N.; Shang, S.; Su, Y. The arginine vasopressin V1b receptor gene and prosociality: Mediation role of emotional empathy. Psych. J. 2015, 4, 160–165.

- Lan, X.Y.; Gu, Y.Y.; Li, M.J.; Song, T.J.; Zhai, F.J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhan, J.S.; Bockers, T.M.; Yue, X.N.; Wang, J.N.; et al. Poly(I:C)-induced maternal immune activation causes elevated self-grooming in male rat offspring: Involvement of abnormal postpartum static nursing in dam. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1054381.

- Morais, L.H.; Felice, D.; Golubeva, A.V.; Moloney, G.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Strain differences in the susceptibility to the gut-brain axis and neurobehavioural alterations induced by maternal immune activation in mice. Behav. Pharmacol. 2018, 29, 181–198.

- Whylings, J.; Rigney, N.; Peters, N.V.; de Vries, G.J.; Petrulis, A. Sexually dimorphic role of BNST vasopressin cells in sickness and social behavior in male and female mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 83, 68–77.

- Taylor, P.V.; Veenema, A.H.; Paul, M.J.; Bredewold, R.; Isaacs, S.; de Vries, G.J. Sexually dimorphic effects of a prenatal immune challenge on social play and vasopressin expression in juvenile rats. Biol. Sex. Differ. 2012, 3, 15.

- Ergaz, Z.; Weinstein-Fudim, L.; Ornoy, A. Genetic and non-genetic animal models for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Reprod. Toxicol. 2016, 64, 116–140.

- Watanabe, T.; Abe, O.; Kuwabara, H.; Yahata, N.; Takano, Y.; Iwashiro, N.; Natsubori, T.; Aoki, Y.; Takao, H.; Kawakubo, Y.; et al. Mitigation of sociocommunicational deficits of autism through oxytocin-induced recovery of medial prefrontal activity: A randomized trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 166–175.

- Hu, L.; Du, X.; Jiang, Z.; Song, C.; Liu, D. Oxytocin treatment for core symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 79, 1357–1363.

More

Information

Subjects:

Neurosciences

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

927

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

14 Dec 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No