Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rafael Alvarez Gutiérrez | -- | 1240 | 2023-12-11 10:59:29 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 1240 | 2023-12-12 02:37:35 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Alvarez Gutiérrez, R.; Blom, J.; Belmans, B.; De Bock, A.; Van Den Bergh, L.; Audenaert, A. Moss-Based Biocomposites. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52571 (accessed on 04 March 2026).

Alvarez Gutiérrez R, Blom J, Belmans B, De Bock A, Van Den Bergh L, Audenaert A. Moss-Based Biocomposites. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52571. Accessed March 04, 2026.

Alvarez Gutiérrez, Rafael, Johan Blom, Bert Belmans, Anouk De Bock, Lars Van Den Bergh, Amaryllis Audenaert. "Moss-Based Biocomposites" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52571 (accessed March 04, 2026).

Alvarez Gutiérrez, R., Blom, J., Belmans, B., De Bock, A., Van Den Bergh, L., & Audenaert, A. (2023, December 11). Moss-Based Biocomposites. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52571

Alvarez Gutiérrez, Rafael, et al. "Moss-Based Biocomposites." Encyclopedia. Web. 11 December, 2023.

Copy Citation

Mosses have a large surface area of densely packed leaves that allows them to effectively trap air pollutants. This enables them to exhibit filtration efficiencies comparable to those of man-made filters. However, within the context of a circular economy, moss fibers integrated into a biocomposite matrix provide the added advantage of being reusable, facilitating the development of closed systems without waste generation.

biocomposites

sphagnum moss

moss wall

natural fibers

air purification

bio-binders

1. Introduction

Being exposed to ambient air pollution is a severe threat to human health causing around 4.2 million deaths every year [1][2][3][4]. Particulate matter (PM) is the main air pollutant in urban environments that causes severe health problems [2][3][5]. These small particles, solids or liquid aerosols, come from a variety of sources, both natural and anthropogenic, such as fossil fuel combustion, construction dust, and industrial processes [6][7]. Mainly, two types are defined based on particle diameter: PM10 are particles with a diameter of 10 µm or less and PM2.5 are particles with a diameter of 2.5 µm. These particles, especially PM2.5, can penetrate deep into the lungs, leading to severe health issues [3][5].

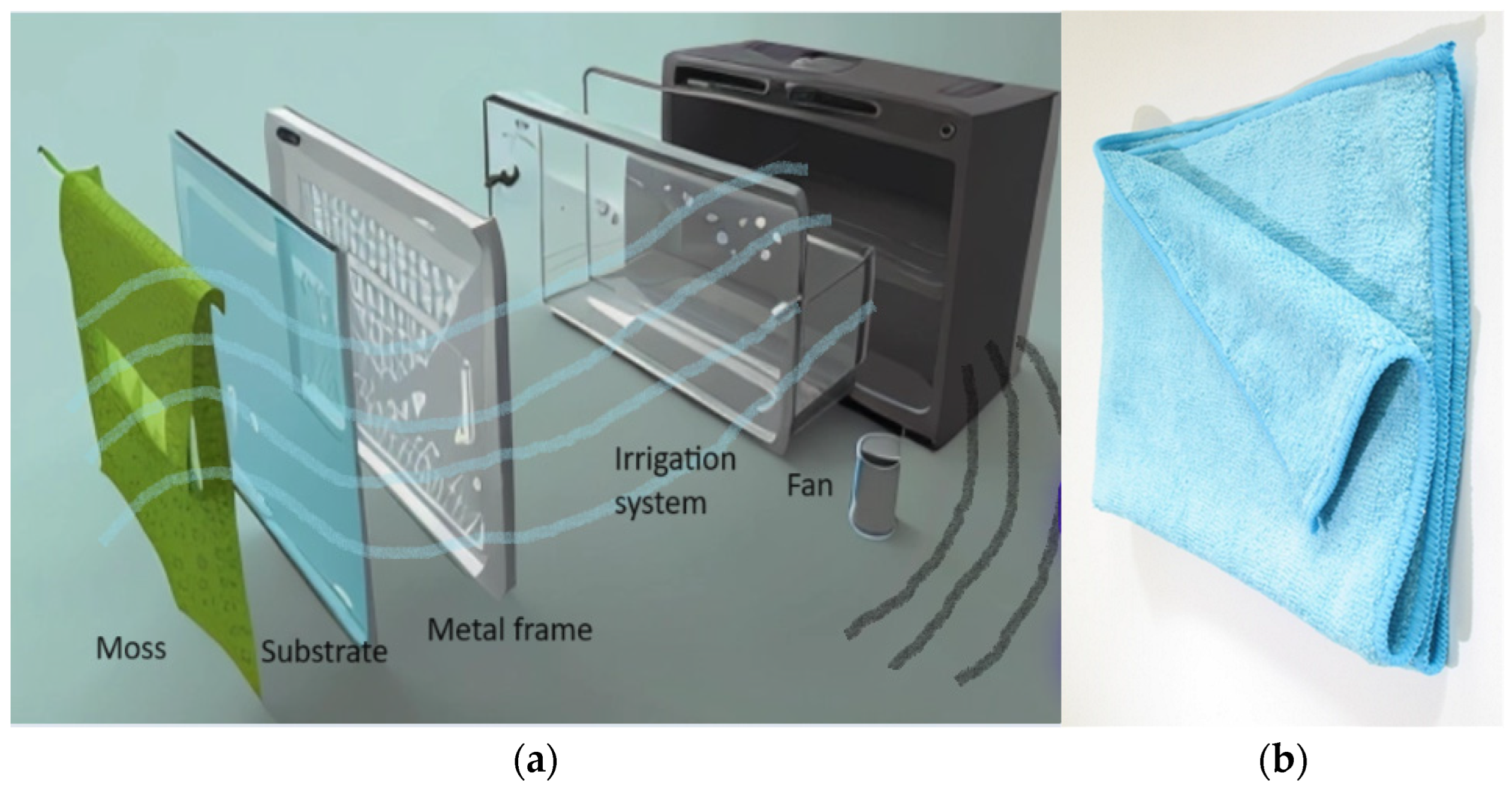

One way to combat air pollution is to address the problem at its source and reduce emissions from polluting activities. Another way is to filter polluted air using active or passive filtration technology [8][9][10][11][12]. Various methods and systems have been introduced to actively filter polluted outdoor air [8][11][12]. Among these are solutions that make use of the air-purifying properties of plants. One such method is the use of ‘moss walls’ [11][12]. These systems, illustrated in Figure 1a, draw in polluted air through ventilation fans installed inside a hollow wall that is covered with ‘moss filters’, passing the stale air through the moss and the substrate on which the moss grows. After filtering, the purified air is released back into the environment. Due to the absence of a developed root system mosses have developed a very high surface area of densely packed leaves to absorb water and nutrients compared to other plants [13][14]. This allows them to trap air pollutants, such as PM, in a very efficient way, similar to manmade filters [15]. Research performed in 2019 at the University of Antwerp has shown that the filtration efficiency of moss panels is 43.1% for PM10 and 22.8% for PM2.5 [16].

Figure 1. (a) Exploded view of existing moss wall; (b) current substrate: synthetic microfiber cloth. The substrate is light blue in color in both images.

To use living moss as part of a filter setup in an air purification system, it needs a breathable and moisture-retaining substrate on which it can grow. Currently, in the moss wall that is the subject of this study, a synthetic microfiber cloth is used for this purpose, see Figure 1b [11][16]. However, this material is highly environmentally polluting as it contains and releases microplastics to the environment, i.e., pieces of plastic less than 5 mm in diameter, that are not degradable and are harmful to various ecosystems [17]. The exposure of microplastics to humans, whether through ingestion or inhalation, can cause potential health risks. These risks include medical conditions, such as gastrointestinal issues, chronic pulmonary diseases, fibrosis in the lungs, and an elevated risk of lung cancer [18][19].

To mitigate the entry of microplastics from the substrate of the moss wall into the environment, this study aims to lay the foundations for a bio-based alternative to microfiber cloth, utilizing excess moss from the system as a raw material. By using saturated moss from the filters and/or excess moss (after cleaning), the system will become more self-sustaining with reduced dependence on external inputs. Therefore, this solution not only addresses immediate environmental concerns but also promotes the circularity of the moss wall.

2. Biocomposite Materials

Biocomposites are materials consisting of a reinforcing phase and a matrix surrounding the reinforcing phase, where at least one of the two is derived from natural sources. They can be categorized based on the type of matrix and fibers they employ, resulting in two main classifications: partially biodegradable and completely biodegradable. Within the category of completely biodegradable biocomposites, bio-fibers are utilized in combination with matrices composed of biodegradable polymers. However, currently, the market for fiber reinforcement is still dominated by synthetic fibers, resulting in mainly partially biodegradable solutions [20]. In many applications, natural fibers are a good alternative to synthetic fibers that are derived from petroleum or other non-renewable resources. This is supported by extended research on the mechanical properties of natural fibers, which exhibit promising similarities to traditional fibers but still have room for further improvement [21]. They are considered to be more environmentally friendly as they are made from renewable resources. Moreover, they have low CO2 emissions during processing, are abundantly available and cheap, and can be recycled or biodegraded at the end of their life [22]. By utilizing these materials, biocomposites can offer a sustainable solution to the disposal management issues faced by certain countries, addressing waste accumulation while promoting resource efficiency [23].

Much progress has already been made in developing methods to make biocomposites using different combinations of natural fibers and binders. In this respect, several recent studies have explored the use of moss-based biocomposites for constructing thermal insulation plates in buildings [24][25][26]. In these studies, Sphagnum moss was used as the main component in combination with various binders, viz., animal glue, liquid glass, and urea-formaldehyde. Biocomposites for thermal insulation applications have also been produced from hemp and flax shives with potato starch as a binder. The aggregate–binder ratio was chosen to be the lowest possible so the sample could withstand its self-weight, resulting in a ratio of 1:3. Starch was prepared using the casting method, whereafter the mixture was compressed and left to dry [21]. Starch is also commonly used in the packaging industry for the preparation of bioplastics. As shown by Marichelvam et al. (2019), the tensile properties of starch are suitable for the production of packing materials, and the preparation method is straightforward [27]. Furthermore, several papers have investigated the use of metakaolin in combination with corn starch to create a biofilm. This combination results in an improvement in the mechanical tensile strength and hydric properties of the obtained biocomposites [28][29]. The use of wood and paper pulp as binders in biocomposites is currently also being researched [30]. Fuentes et al. (2021) developed biodegradable pots based on different waste materials such as, among others, used paper, wheat flour, and corn-waste flour [31]. Additionally, a combination of wooden fibers and peat moss has been used for the design of biodegradable pots, containing 80% wooden fibers and 20% peat moss, to improve the uptake of water [32].

To conclude, the growing interest in biocomposites offers numerous opportunities to develop sustainable materials for diverse applications. Although there is a lot of ongoing research on natural fibers and biodegradable polymers to replace petroleum-based products, the development of fully biodegradable biocomposites is still in its early stages. Moreover, the integration of moss fibers alongside other natural fibers and biodegradable polymers to develop biocomposites, other than for insulation purposes, remains a relatively unexplored topic. In the broader context of continuous research on moss walls for urban air purification, and with the aim of advancing the state of the art in (moss-based) biocomposites, this study therefore explores the feasibility of creating a new fully biodegradable, moss-based biocomposite. In the first instance, the objective is to develop a material that uses excess moss from the system as a raw material and that can support its own weight while preserving its structural integrity. Consequently, this preliminary investigation stands as a meaningful contribution to ongoing research efforts and advancing the current state of the art.

References

- WHO. Air Quality and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/air-quality-and-health/sectoral-interventions/ambient-air-pollution/health-risks (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Ysebaert, T.; Koch, K.; Samson, R.; Denys, S. Green Walls for Mitigating Urban Particulate Matter Pollution—A Review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 59, 127014.

- European Environment Agency. Air Pollution: How It Affects Our Health. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/air/health-impacts-of-air-pollution#:~:text=Both%20short%2D%20and%20long%2Dterm,asthma%20and%20lower%20respiratory%20infections (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- European Environment Agency. Premature Deaths Due to Exposure to Fine Particulate Matter in Europe. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/ims/health-impacts-of-exposure-to (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- EPA Health and Environmental Effects of Particulate Matter (PM). Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/health-and-environmental-effects-particulate-matter-pm (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Ji, X.; Huang, J.; Teng, L.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Cai, W.; Chen, Z.; Lai, Y. Advances in Particulate Matter Filtration: Materials, Performance, and Application. Green Energy Environ. 2023, 8, 673–697.

- Wade, J.; Farrauto, R.J. 12—Controlling Emissions of Pollutants in Urban Areas. In Metropolitan Sustainability; Zeman, F., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 260–291. ISBN 978-0-85709-046-1.

- Blocken, B.; Vervoort, R.; van Hooff, T. Reduction of Outdoor Particulate Matter Concentrations by Local Removal in Semi-Enclosed Parking Garages: A Preliminary Case Study for Eindhoven City Center. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2016, 159, 80–98.

- Perini, K.; Castellari, P.; Gisotti, D.; Giachetta, A.; Turcato, C.; Roccotiello, E. MosSkin: A Moss-Based Lightweight Building System. Build. Environ. 2022, 221, 109283.

- European Commission. Ceramic Honeycomb Air Filters Could Cut City Pollution. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research-and-innovation/en/horizon-magazine/ceramic-honeycomb-air-filters-could-cut-city-pollution (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- BESIX. BESIX: Proefproject “Clean Air” Tegen Fijnstof. Available online: https://press.besix.com/besix-proefproject-clean-air-tegen-fijnstof (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Green City Solutions the Citytree. Available online: https://greencitysolutions.de/en/citytree/ (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Whitton, J. Plant Biodiversity, Overview, 2nd ed.; Levin, S.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013.

- EnGreDi Mosses. Available online: https://www.engredi.be/mosses (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- European Commission. Using Moss to Measure Air Pollution. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/horizon2020/items/15130#:~:text=%E2%80%9CMosses%20lack%20a%20root%20system,and%20gaseous%2C%E2%80%9D%20he%20adds (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- BESIX BESIX Clean Air Neemt Een Groeispurt, Net Als Haar Mossen. Available online: https://www.besix.com/nl/news/besix-clean-air-neemt-een-groeispurt-net-als-haar-mossen (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Microplastics Research. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/water-research/microplastics-research (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Jahandari, A. Microplastics in the Urban Atmosphere: Sources, Occurrences, Distribution, and Potential Health Implications. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2023, 12, 100346.

- Nguyen, M.-K.; Lin, C.; Nguyen, H.-L.; Le, V.-R.; KL, P.; Singh, J.; Chang, S.W.; Um, M.-J.; Nguyen, D.D. Emergence of Microplastics in the Aquatic Ecosystem and Their Potential Effects on Health Risks: The Insights into Vietnam. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118499.

- de Smet, D.; Goethals, F.; Demedts, B.; Uyttendaele, W.; Vanneste, M. Bio-Based Textile Coatings and Composites. In Biobased Products and Industries; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 357–402. ISBN 9780128201534.

- Vitola, L.; Gendelis, S.; Sinka, M.; Pundiene, I.; Bajare, D. Assessment of Plant Origin By-Products as Lightweight Aggregates for Bio-Composite Bounded by Starch Binder. Energies 2022, 15, 5330.

- Faruk, O.; Bledzki, A.K.; Fink, H.P.; Sain, M. Biocomposites Reinforced with Natural Fibers: 2000–2010. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 1552–1596.

- Madurwar, M.V.; Ralegaonkar, R.V.; Mandavgane, S.A. Application of Agro-Waste for Sustainable Construction Materials: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 872–878.

- Kain, G.; Idam, F.; Tonini, S.; Wimmer, A. Torfmoos (Sphagnum)—Historisches Erfahrungswissen Und Neue Einsatzmöglichkeiten Für Ein Naturprodukt. Bauphysik 2019, 41, 199–204.

- Morandini, M.C.; Kain, G.; Eckardt, J.; Petutschnigg, A.; Tippner, J. Physical-Mechanical Properties of Peat Moss (Sphagnum) Insulation Panels with Bio-Based Adhesives. Materials 2022, 15, 3299.

- Bakatovich, A.; Gaspar, F. Composite Material for Thermal Insulation Based on Moss Raw Material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 228, 116699.

- Marichelvam, M.K.; Jawaid, M.; Asim, M. Corn and Rice Starch-Based Bio-Plastics as Alternative Packaging Materials. Fibers 2019, 7, 32.

- Méité, N.; Konan, L.K.; Tognonvi, M.T.; Oyetola, S. Effect of Metakaolin Content on Mechanical and Water Barrier Properties of Cassava Starch Films. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 40, 186–194.

- Lorente-Ayza, M.-M.; Sánchez, E.; Sanz, V.; Mestre, S. Influence of Starch Content on the Properties of Low-Cost Microfiltration Ceramic Membranes. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 13064–13073.

- Ferrari, F.; Striani, R.; Fico, D.; Alam, M.M.; Greco, A.; Esposito Corcione, C. An Overview on Wood Waste Valorization as Biopolymers and Biocomposites: Definition, Classification, Production, Properties and Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 5519.

- Fuentes, R.A.; Berthe, J.A.; Barbosa, S.E.; Castillo, L.A. Development of Biodegradable Pots from Different Agroindustrial Wastes and Byproducts. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2021, 30, e00338.

- Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y. Properties of Selected Biodegradable Seedling Plug-Trays. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 249, 177–184.

More

Information

Subjects:

Materials Science, Biomaterials

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

855

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

12 Dec 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No