Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kelsie Lynn Thu | -- | 2313 | 2023-11-09 17:00:25 | | | |

| 2 | Jason Zhu | Meta information modification | 2313 | 2023-11-10 02:33:54 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Lau, A.P.Y.; Khavkine Binstock, S.S.; Thu, K.L. Implications of CD47 in Tumor Biology. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51379 (accessed on 08 March 2026).

Lau APY, Khavkine Binstock SS, Thu KL. Implications of CD47 in Tumor Biology. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51379. Accessed March 08, 2026.

Lau, Asa P. Y., Sharon S. Khavkine Binstock, Kelsie L. Thu. "Implications of CD47 in Tumor Biology" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51379 (accessed March 08, 2026).

Lau, A.P.Y., Khavkine Binstock, S.S., & Thu, K.L. (2023, November 09). Implications of CD47 in Tumor Biology. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51379

Lau, Asa P. Y., et al. "Implications of CD47 in Tumor Biology." Encyclopedia. Web. 09 November, 2023.

Copy Citation

Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide. Despite treatment advances, high rates of tumor recurrence emphasize the need for new therapeutic strategies. Tumors often acquire mechanisms to avoid detection by the immune system, allowing them to develop and metastasize. Immunotherapy is a type of treatment designed to overcome these mechanisms by reactivating the immune system to eliminate tumors. CD47 is a cell surface protein and marker of “self” expressed on cells throughout the body and prevents them from being “eaten” by cells of the immune system. CD47 has also been described to have immune-independent functions in normal and malignant cells which could contribute to tumor growth and progression.

CD47

immune checkpoint inhibitors

non-small cell lung cancer

1. CD47 Is a Ubiquitously Expressed Transmembrane Protein Upregulated in Cancer

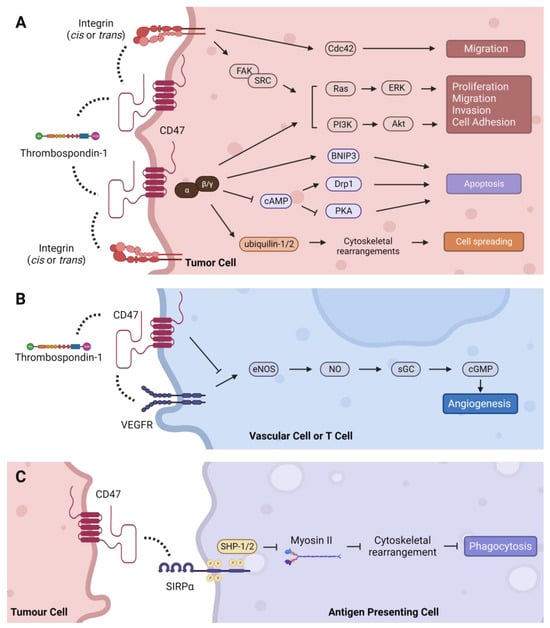

CD47, also known as integrin-associated protein (IAP), is a 50 kDa cell surface protein with an IgV-like extracellular N terminal domain, five transmembrane domains, and a C-terminal cytoplasmic tail with four isoforms [1]. Structurally, the IgV-like extracellular domain is composed of two beta-sheets linked by a cysteine bridge and tethers CD47 to the cell membrane [2][3]. A number of post-translational modifications on CD47 have been identified, including ubiquitination, phosphorylation, and glycosylation, as well as pyroglutamate and heparan sulfate modifications that alter its structure, expression, localization, and function [2][4][5][6][7][8]. The extracellular domain of CD47 binds to multiple ligands, while the cytoplasmic domain associates with Gi and other proteins [9][10]. These interactions transduce signals that regulate a plethora of cellular processes in diverse cell types as summarized below [11][12] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Intracellular signaling pathways regulated by CD47. (A) TSP-1 can indirectly activate integrin signaling through CD47 to stimulate Cdc42, as well as the Ras/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways via FAK/SRC to regulate tumor-promoting processes such as cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and adhesion. CD47 signals through Gi proteins to promote cell proliferation through the PI3K/Akt pathway and cell spreading via direct association with ubiquilins. CD47-Gi interaction also regulates apoptosis by inhibiting cAMP-dependent signaling pathways, and CD47 can induce apoptosis directly through its interaction with BNIP3. (B) TSP-1 mediated inhibition of angiogenesis is CD47-dependent. Binding of TSP-1 to CD47 causes CD47 to dissociate from VEGFR2 and inhibits phosphorylation of VEGFR2, thereby suppressing the angiogenesis pathway. (C) CD47 binding to SIRPα initiates a signaling cascade that inhibits phagocytosis in macrophages and dendritic cells. Dashed lines indicate protein interactions.

CD47 is expressed in cells and tissues throughout the body, with relatively high levels on cells derived from the hematopoietic system including erythrocytes (red blood cells, RBCs) and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells [1][13][14][15][16][17][18]. CD47 is also expressed as a >250 kDa proteoglycan on T cells, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells [4]. Oldenborg and colleagues reported CD47 as a “marker of self” after discovering that RBCs lacking CD47 were eliminated by splenic macrophages [15]. Subsequent studies found that CD47 expression on RBCs decreases over their lifetime to mark aged cells for phagocytic clearance [14][19]. Regulation of platelet homeostasis via CD47 expression has also been described [20]. Upon recognition of its role in inhibiting phagocytosis, akin to CD31 disabling phagocytosis of viable cells, CD47 was later coined a “don’t eat me” signal [21]. CD47 is upregulated in many malignancies, and the first observations of cancer-associated CD47 overexpression were made in ovarian cancer [22][23]. Since then, CD47 expression has been described in various tumor types including NSCLC and SCLC, with numerous studies reporting its association with tumor stage and patient survival.

2. Regulation of CD47 Expression in Cancer

Several mechanisms have been described to regulate CD47 transcription in cancer cells [24]. Expression of CD47 can be controlled by cytokines, oncogenes, and micro-RNAs (miRNA). In liver and breast cancer cells, TNFα induces CD47 expression through the transcriptional regulator, NF-κB [25][26]. In melanoma models, CD47 expression was induced by IFNγ, although the exact mechanism remains to be elucidated [27][28]. Interleukins also appear to upregulate CD47 expression. IL-6 induced CD47 through STAT3 in hepatoma cells, and IL-1β induced CD47 via NF-κB in cervical cancer cells [29][30]. CD47 induction by IL-4, IL-7, and IL-13 has also been described, but how these interleukins stimulate CD47 transcription is unknown [30][31]. These immune-stimulating, pro-inflammatory cytokines may be physiologically programmed to induce CD47 expression, like PD-L1, as a negative feedback mechanism to prevent harmful overactivation of the immune response. Both MYC and HIF-1A oncogenes have been shown to directly bind the CD47 promoter and induce its transcription in breast, leukemia, and lymphoma models [32][33]. On the contrary, multiple miRNA have been shown to negatively regulate CD47 expression in several cancer types by degrading CD47 transcripts or blocking protein translation. These include miR-133a, miR-155, miR-192, miR-200a, miR-222, miR-340, and miR-708 [24]. Two recent studies established novel mechanisms of CD47 expression regulation by the oncogenic drivers, EGFR and KRAS. In NSCLC, KRAS was discovered to upregulate CD47 by suppressing miR-34a [34]. Specifically, KRAS-mediated activation of PI3K-AKT signaling led to the phosphorylation of STAT3 and its transcriptional repression of miR-34a, thereby relieving post-transcriptional inhibition of CD47 and increasing its expression. Similarly, EGFR was found to upregulate CD47 by stabilizing its expression. In glioblastoma models, EGFR activation induced c-Src-mediated phosphorylation of CD47, which prevented its interaction with the E3 ubiquitin ligase, TRIM21, and protected CD47 from ubiquitin-associated degradation [8].

3. CD47: Molecular Interactions, Signaling Pathways, and Malignant Phenotypes

CD47 regulates various signaling cascades by interacting with different proteins including those located intra- or extracellularly, within the plasma membrane or in the extracellular matrix (ECM). These interactions occur in either a cis (same cell) or trans (different cell) manner and are dependent upon CD47′s IgV-like, transmembrane, and cytoplasmic tail domains. The most well characterized CD47 interaction partners include thrombospondin-1, integrins, and members of the signal-regulatory protein (SIRP) family, which signal through CD47 to promote various hallmarks of cancer.

3.1. Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1)—Proliferation, Migration, Cell Death, and Angiogenesis

TSP-1 is an extracellular matrix (ECM) glycoprotein secreted by platelets, macrophages, dendritic cells, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and epithelial cells in response to stress, as well as tumor and stromal cells in the TME. TSP-1 interacts with many proteins including integrins, collagen, fibrinogen, laminin, proteases, and growth factors to regulate diverse physiological processes such as vascular response to injury, inflammation, platelet activation, and ECM remodeling [35][36]. The cellular effects of TSP-1 are dependent on tissue-specific expression of its receptors and other interacting partners in the local environment. The C-terminal domain of TSP-1 binds the extracellular region of CD47 at picomolar concentrations to control motility, proliferation, and angiogenesis that influence the invasive and metastatic properties of cancer cells [35]. For example, CD47–TSP-1 interaction promoted tumor progression in a T cell lymphoma model by supporting proliferation, survival, and migration via activation of ERK, AKT and survivin signaling [37]. Similarly, antibody-mediated cross-linking of CD47 on T cells stimulates their activation and proliferation [38][39]. In contrast, TSP-1-induced cell death in leukemia, lung, breast, and colon cancer cell lines in a CD47-dependent, caspase-independent manner [40][41][42]. In non-malignant T cells, binding of CD47 by TSP-1 has been shown to induce caspase-independent apoptosis and stimulate migration, and to suppress activation-induced proliferation, CD69 expression, and IL-2 production, further illustrating the context-specific effects of CD47–TSP-1 interactions [4][43][44][45][46]. CD47–TSP-1 binding has also been implicated in mediating sensitivity to cancer therapies. Interaction of CD47 and TSP-1 blocked the escape of breast and colorectal cancer cells from chemotherapy-induced senescence and sensitized melanoma cells to radiotherapy in a cell autonomous manner [47][48]. CD47 blockade also protected mice from lethal whole-body irradiation that was associated with an increase in autophagy in surviving cells [49]. However, the specific mechanisms explaining these responses to therapy remain to be defined.

Studies in endothelial cell models have deduced a role for CD47 in regulating angiogenesis through the VEGFR2 signaling pathway [11][50]. First, CD47 was found to be essential for TSP-1-mediated inhibition of nitric oxide-stimulated responses in vascular cells [51]. It was later discovered that CD47 physically associates with VEGFR2 in endothelial and T cells, and that CD47 ligation by TSP-1 disrupts this physical interaction with VEGFR2, which inhibits its phosphorylation and downstream signaling [52][53]. It is unclear how the CD47–TSP-1–VEGFR2 axis influences angiogenesis in tumors because of conflicting findings in tumor models, which may be confounded by irregularities in tumor vasculature and the enigmatic role of nitric oxide in regulating tumor angiogenesis [54]. Studies in melanoma and breast tumors found that TSP-1 overexpression in cancer cells negatively regulated tumor blood flow in response to vasoactive agents in a CD47-dependent manner [55]. Recent studies reported that disrupting the CD47–TSP-1 interaction reduced angiogenesis in neuroblastoma and glioblastoma models, but selectively depleting CD47 in stromal cells increased angiogenesis and tumor burden in a syngeneic prostate cancer model [56][57]. Furthermore, inhibition of CD47 normalized tumor vasculature in a multiple myeloma model, which was associated with reduced expression of pro-angiogenic factors, increased expression of anti-angiogenic factors, and tumor growth inhibition [58]. Thus, the effects of TSP-1-CD47 interactions on angiogenesis may be malignancy-dependent, and further studies are needed to fully understand them.

3.2. Integrins—Migration, Invasion, and Inflammation

CD47 was originally named integrin-associated protein (IAP) because it was discovered that it binds with several members of the integrin family of transmembrane receptors, including integrins αvβ3, αIIbβ3, and αβ1 [10]. Subsequently, CD47 has been shown to interact with α5, α4β1, α6β1, among others [50]. Integrins facilitate cellular attachment to the ECM via the actin cytoskeleton and regulate focal adhesion kinase (FAK), integrin-linked kinase (ILK), and SRC kinase signaling pathways including Ras-ERK, PI3K/AKT, and YAP/TAZ, which support tumor growth and progression [59]. Lateral (cis) interactions between CD47 and integrins form signaling complexes that can activate integrins and influence binding to ECM proteins [12][50]. They also promote migration and metastasis phenotypes in a seemingly cancer-specific manner [12], which may be explained by differences in integrin expression across cancer types. Interactions between CD47 and αvβ3 enhanced binding of ovarian and breast cancer cells and spreading of melanoma cells on vitronectin-coated substrates, as well as chemotaxis of prostate cancer and melanoma cells towards collagen [60][61][62][63]. CD47-α4β1 interactions stimulated adhesion in melanoma, lymphoma, and T cells, and promoted migration in B-cell leukemia models [64][65][66]. Notably, many of these processes are dependent on the ligation of CD47 by TSP-1, TSP-1-derived peptides (e.g., 4N1K), or anti-CD47 antibodies. In addition to these cancer cell-intrinsic effects, CD47–integrin interactions can influence tumor immunity by modifying the behavior of immune cells in the TME [10]. For instance, CD47-blocking antibodies inhibited CD23-stimulated secretion of several pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNFα, IL-1β, and PGE2 from monocytes and IFNγ from T cells through a CD47–αvβ3 complex [67]. Consistently, CD47 ligation with antibodies or 4N1K suppressed IL-12 release from monocytes and inhibited the transition of naive T cells to Th1 effector cells [68][69]. Additional mechanistic studies to investigate CD47–integrin interactions in different cancer models are needed to better understand the generalizability of their cellular effects.

3.3. SIRPα/γ—Phagocytosis and Tumor Immune Evasion

The SIRP family is a group of cell surface receptors primarily expressed on myeloid cells [70]. Of the three identified members, SIRPα binds CD47 with the highest affinity and is expressed on macrophages, dendritic cells, T cells, hematopoietic progenitor cells, and neurons [9]. Hatherley et al. identified five key residues (Y37D, D46K, E97K, E100K, E106K) in the extracellular domain of human CD47 that are critical for binding to SIRPα [2]. In addition, Gln-19 must be enzymatically modified to pyrrolidone carboxylic acid (pyroglutamate) for SIRPα to bind CD47 [6]. CD47–SIRPα interaction initiates a signaling cascade that inhibits phagocytosis, and this pathway has been the primary focus for developing CD47-targeted therapies. Upon CD47–SIRPα ligation, the intracellular immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM)-domain in the cytoplasmic tail of SIRPα is phosphorylated. This recruits the inhibitory phosphatases, SHP-1 and SHP-2, which dephosphorylate myosin II, thereby preventing reorganization of the cytoskeleton that is required for phagocytosis to occur [71]. Consequently, antigen uptake and presentation by APCs and subsequent activation of the adaptive immune response is inhibited [72]. In addition to SIRPα, SIRPγ also binds to CD47 but with ten times lower affinity [73]. SIRPγ is expressed on NK cells and lymphocytes, and studies have shown that CD47–SIRPγ interactions positively regulate T cell transendothelial migration, T cell activation, and apoptosis of Jurkat cells, which could be undesirably impaired by CD47 blockade [73][74][75][76].

3.4. Intracellular Interactions and Signaling

Many of the interactions described above transduce extracellular signals to intracellular molecules bound to CD47′s cytoplasmic tail to elicit associated cellular effects. Initially, CD47 was co-immunoprecipitated with heterotrimeric Gi proteins in membranes isolated from platelets, melanoma, and ovarian cancer cells, which was reversible by the potent inhibitor of receptor–Gi protein binding, pertussis toxin [77]. Evidence that CD47 activates Gi proteins was provided by the finding that 4N1K ligation decreased intracellular cAMP levels [77]. Later studies found that CD47 interacts with two ubiquitin-related proteins involved in protein degradation, ubiquilin-1 and ubiquilin 2, via tethering to CD47 by Gβγ [78][79][80]. This interaction induced cytoskeletal rearrangements and enhanced spreading of Jurkat and ovarian cancer cells [79]. Subsequently, the CD47–Giαβγ pathway was shown to activate PI3K/Akt signaling to induce proliferation in astrocytoma cells [81]. Additional cytoplasmic signaling cascades regulated by TSP-1–CD47-mediated Gi activation and consequential reductions in cAMP levels include the phosphorylation of SYK and LYN and their interaction with FAK during platelet aggregation; phosphorylation of ERK during smooth muscle cell migration and T cell lymphoma migration and adhesion; and inhibition of PKA during apoptosis in activated T cells [37][65][82][83][84]. In addition to Gi proteins, the cytoplasmic domain of CD47 has also been shown to directly interact with the BCL-2 family member, BNIP3, to induce a necrosis-like mode of caspase-independent T cell death upon CD47 ligation with TSP-1 [45]. Most recently, c-Src was reported to bind and phosphorylate CD47 in an EGFR-dependent manner, which led to CD47 stabilization and immune evasion in a glioblastoma model [8]. Besides these direct physical associations, CD47 has been discovered to indirectly interact with several other cytoplasmic proteins to regulate various cancer-relevant processes. These include interactions with Cdc42, Drp1, and guanylate cyclase (GC), as well as regulation of autophagy proteins that collectively influence cell death and survival, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis [11][49][50][85][86].

References

- Reinhold, M.I.; Lindberg, F.P.; Plas, D.; Reynolds, S.; Peters, M.G.; Brown, E.J. In Vivo Expression of Alternatively Spliced Forms of Integrin-Associated Protein (CD47). J. Cell Sci. 1995, 108 Pt 11, 3419–3425.

- Hatherley, D.; Graham, S.C.; Turner, J.; Harlos, K.; Stuart, D.I.; Barclay, A.N. Paired Receptor Specificity Explained by Structures of Signal Regulatory Proteins Alone and Complexed with CD47. Mol. Cell 2008, 31, 266–277.

- Rebres, R.A.; Vaz, L.E.; Green, J.M.; Brown, E.J. Normal Ligand Binding and Signaling by CD47 (Integrin-Associated Protein) Requires a Long Range Disulfide Bond between the Extracellular and Membrane-Spanning Domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 34607–34616.

- Kaur, S.; Kuznetsova, S.A.; Pendrak, M.L.; Sipes, J.M.; Romeo, M.J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Roberts, D.D. Heparan Sulfate Modification of the Transmembrane Receptor CD47 Is Necessary for Inhibition of T Cell Receptor Signaling by Thrombospondin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 14991–15002.

- Kim, W.; Bennett, E.J.; Huttlin, E.L.; Guo, A.; Li, J.; Possemato, A.; Sowa, M.E.; Rad, R.; Rush, J.; Comb, M.J.; et al. Systematic and Quantitative Assessment of the Ubiquitin-Modified Proteome. Mol. Cell 2011, 44, 325–340.

- Logtenberg, M.E.W.; Jansen, J.H.M.; Raaben, M.; Toebes, M.; Franke, K.; Brandsma, A.M.; Matlung, H.L.; Fauster, A.; Gomez-Eerland, R.; Bakker, N.A.M.; et al. Glutaminyl Cyclase Is an Enzymatic Modifier of the CD47- SIRPα Axis and a Target for Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 612–619.

- Parthasarathy, R.; Subramanian, S.; Boder, E.T.; Discher, D.E. Post-Translational Regulation of Expression and Conformation of an Immunoglobulin Domain in Yeast Surface Display. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2006, 93, 159–168.

- Du, L.; Su, Z.; Wang, S.; Meng, Y.; Xiao, F.; Xu, D.; Li, X.; Qian, X.; Lee, S.B.; Lee, J.-H.; et al. EGFR-Induced and c-Src-Mediated CD47 Phosphorylation Inhibits TRIM21-Dependent Polyubiquitylation and Degradation of CD47 to Promote Tumor Immune Evasion. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2206380.

- Murata, Y.; Kotani, T.; Ohnishi, H.; Matozaki, T. The CD47-SIRPα Signalling System: Its Physiological Roles and Therapeutic Application. J. Biochem. 2014, 155, 335–344.

- Brown, E.J.; Frazier, W.A. Integrin-Associated Protein (CD47) and Its Ligands. Trends Cell Biol. 2001, 11, 130–135.

- Bian, H.-T.; Shen, Y.-W.; Zhou, Y.-D.; Nagle, D.G.; Guan, Y.-Y.; Zhang, W.-D.; Luan, X. CD47: Beyond an Immune Checkpoint in Cancer Treatment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2022, 1877, 188771.

- Soto-Pantoja, D.R.; Kaur, S.; Roberts, D.D. CD47 Signaling Pathways Controlling Cellular Differentiation and Responses to Stress. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 50, 212–230.

- Jaiswal, S.; Jamieson, C.H.M.; Pang, W.W.; Park, C.Y.; Chao, M.P.; Majeti, R.; Traver, D.; van Rooijen, N.; Weissman, I.L. CD47 Is Upregulated on Circulating Hematopoietic Stem Cells and Leukemia Cells to Avoid Phagocytosis. Cell 2009, 138, 271–285.

- Khandelwal, S.; van Rooijen, N.; Saxena, R.K. Reduced Expression of CD47 during Murine Red Blood Cell (RBC) Senescence and Its Role in RBC Clearance from the Circulation. Transfusion 2007, 47, 1725–1732.

- Oldenborg, P.A.; Zheleznyak, A.; Fang, Y.F.; Lagenaur, C.F.; Gresham, H.D.; Lindberg, F.P. Role of CD47 as a Marker of Self on Red Blood Cells. Science 2000, 288, 2051–2054.

- Mawby, W.J.; Holmes, C.H.; Anstee, D.J.; Spring, F.A.; Tanner, M.J. Isolation and Characterization of CD47 Glycoprotein: A Multispanning Membrane Protein Which Is the Same as Integrin-Associated Protein (IAP) and the Ovarian Tumour Marker OA3. Biochem. J. 1994, 304 Pt 2, 525–530.

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Proteomics. Tissue-Based Map of the Human Proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419.

- Thul, P.J.; Åkesson, L.; Wiking, M.; Mahdessian, D.; Geladaki, A.; Ait Blal, H.; Alm, T.; Asplund, A.; Björk, L.; Breckels, L.M.; et al. A Subcellular Map of the Human Proteome. Science 2017, 356, eaal3321.

- Fossati-Jimack, L.; Azeredo da Silveira, S.; Moll, T.; Kina, T.; Kuypers, F.A.; Oldenborg, P.-A.; Reininger, L.; Izui, S. Selective Increase of Autoimmune Epitope Expression on Aged Erythrocytes in Mice: Implications in Anti-Erythrocyte Autoimmune Responses. J. Autoimmun. 2002, 18, 17–25.

- Olsson, M.; Bruhns, P.; Frazier, W.A.; Ravetch, J.V.; Oldenborg, P.-A. Platelet Homeostasis Is Regulated by Platelet Expression of CD47 under Normal Conditions and in Passive Immune Thrombocytopenia. Blood 2005, 105, 3577–3582.

- Brown, S.; Heinisch, I.; Ross, E.; Shaw, K.; Buckley, C.D.; Savill, J. Apoptosis Disables CD31-Mediated Cell Detachment from Phagocytes Promoting Binding and Engulfment. Nature 2002, 418, 200–203.

- Massuger, L.F.; Claessens, R.A.; Kenemans, P.; Verheijen, R.H.; Boerman, O.C.; Meeuwis, A.P.; Schijf, C.P.; Buijs, W.C.; Hanselaar, T.G.; Corstens, F.H. Kinetics and Biodistribution in Relation to Tumour Detection with 111In-Labelled OV-TL 3 F(ab’)2 in Patients with Ovarian Cancer. Nucl. Med. Commun. 1991, 12, 593–609.

- Campbell, I.G.; Freemont, P.S.; Foulkes, W.; Trowsdale, J. An Ovarian Tumor Marker with Homology to Vaccinia Virus Contains an IgV-like Region and Multiple Transmembrane Domains. Cancer Res. 1992, 52, 5416–5420.

- Huang, C.-Y.; Ye, Z.-H.; Huang, M.-Y.; Lu, J.-J. Regulation of CD47 Expression in Cancer Cells. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 13, 100862.

- Betancur, P.A.; Abraham, B.J.; Yiu, Y.Y.; Willingham, S.B.; Khameneh, F.; Zarnegar, M.; Kuo, A.H.; McKenna, K.; Kojima, Y.; Leeper, N.J.; et al. A CD47-Associated Super-Enhancer Links pro-Inflammatory Signalling to CD47 Upregulation in Breast Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14802.

- Lo, J.; Lau, E.Y.T.; Ching, R.H.H.; Cheng, B.Y.L.; Ma, M.K.F.; Ng, I.O.L.; Lee, T.K.W. Nuclear Factor Kappa B-Mediated CD47 up-Regulation Promotes Sorafenib Resistance and Its Blockade Synergizes the Effect of Sorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Mice. Hepatology 2015, 62, 534–545.

- Sockolosky, J.T.; Dougan, M.; Ingram, J.R.; Ho, C.C.M.; Kauke, M.J.; Almo, S.C.; Ploegh, H.L.; Garcia, K.C. Durable Antitumor Responses to CD47 Blockade Require Adaptive Immune Stimulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E2646–E2654.

- Basile, M.S.; Mazzon, E.; Russo, A.; Mammana, S.; Longo, A.; Bonfiglio, V.; Fallico, M.; Caltabiano, R.; Fagone, P.; Nicoletti, F.; et al. Differential Modulation and Prognostic Values of Immune-Escape Genes in Uveal Melanoma. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210276.

- Chen, J.; Zheng, D.-X.; Yu, X.-J.; Sun, H.-W.; Xu, Y.-T.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Xu, J. Macrophages Induce CD47 Upregulation via IL-6 and Correlate with Poor Survival in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, e1652540.

- Liu, F.; Dai, M.; Xu, Q.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Y.; Ai, Z.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. SRSF10-Mediated IL1RAP Alternative Splicing Regulates Cervical Cancer Oncogenesis via mIL1RAP-NF-κB-CD47 Axis. Oncogene 2018, 37, 2394–2409.

- Johnson, L.D.S.; Banerjee, S.; Kruglov, O.; Viller, N.N.; Horwitz, S.M.; Lesokhin, A.; Zain, J.; Querfeld, C.; Chen, R.; Okada, C.; et al. Targeting CD47 in Sézary Syndrome with SIRPαFc. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 1145–1153.

- Casey, S.C.; Tong, L.; Li, Y.; Do, R.; Walz, S.; Fitzgerald, K.N.; Gouw, A.M.; Baylot, V.; Gütgemann, I.; Eilers, M.; et al. MYC Regulates the Antitumor Immune Response through CD47 and PD-L1. Science 2016, 352, 227–231.

- Zhang, H.; Lu, H.; Xiang, L.; Bullen, J.W.; Zhang, C.; Samanta, D.; Gilkes, D.M.; He, J.; Semenza, G.L. HIF-1 Regulates CD47 Expression in Breast Cancer Cells to Promote Evasion of Phagocytosis and Maintenance of Cancer Stem Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E6215–E6223.

- Hu, H.; Cheng, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Kong, Y.; Zhan, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, H.; Yu, R.; et al. Oncogenic KRAS Signaling Drives Evasion of Innate Immune Surveillance in Lung Adenocarcinoma by Activating CD47. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 133, e153470.

- Kale, A.; Rogers, N.M.; Ghimire, K. Thrombospondin-1 CD47 Signalling: From Mechanisms to Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4062.

- Kaur, S.; Bronson, S.M.; Pal-Nath, D.; Miller, T.W.; Soto-Pantoja, D.R.; Roberts, D.D. Functions of Thrombospondin-1 in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4570.

- Kamijo, H.; Miyagaki, T.; Takahashi-Shishido, N.; Nakajima, R.; Oka, T.; Suga, H.; Sugaya, M.; Sato, S. Thrombospondin-1 Promotes Tumor Progression in Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma via CD47. Leukemia 2020, 34, 845–856.

- Ticchioni, M.; Deckert, M.; Mary, F.; Bernard, G.; Brown, E.J.; Bernard, A. Integrin-Associated Protein (CD47) Is a Comitogenic Molecule on CD3-Activated Human T Cells. J. Immunol. 1997, 158, 677–684.

- Waclavicek, M.; Majdic, O.; Stulnig, T.; Berger, M.; Baumruker, T.; Knapp, W.; Pickl, W.F. T Cell Stimulation via CD47: Agonistic and Antagonistic Effects of CD47 Monoclonal Antibody 1/1A4. J. Immunol. 1997, 159, 5345–5354.

- Saumet, A.; Slimane, M.B.; Lanotte, M.; Lawler, J.; Dubernard, V. Type 3 repeat/C-Terminal Domain of Thrombospondin-1 Triggers Caspase-Independent Cell Death through CD47/alphavbeta3 in Promyelocytic Leukemia NB4 Cells. Blood 2005, 106, 658–667.

- Denèfle, T.; Boullet, H.; Herbi, L.; Newton, C.; Martinez-Torres, A.-C.; Guez, A.; Pramil, E.; Quiney, C.; Pourcelot, M.; Levasseur, M.D.; et al. Thrombospondin-1 Mimetic Agonist Peptides Induce Selective Death in Tumor Cells: Design, Synthesis, and Structure-Activity Relationship Studies. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 8412–8421.

- Mateo, V.; Lagneaux, L.; Bron, D.; Biron, G.; Armant, M.; Delespesse, G.; Sarfati, M. CD47 Ligation Induces Caspase-Independent Cell Death in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 1277–1284.

- Miller, T.W.; Kaur, S.; Ivins-O’Keefe, K.; Roberts, D.D. Thrombospondin-1 Is a CD47-Dependent Endogenous Inhibitor of Hydrogen Sulfide Signaling in T Cell Activation. Matrix Biol. 2013, 32, 316–324.

- Li, Z.; He, L.; Wilson, K.; Roberts, D. Thrombospondin-1 Inhibits TCR-Mediated T Lymphocyte Early Activation. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 2427–2436.

- Lamy, L.; Ticchioni, M.; Rouquette-Jazdanian, A.K.; Samson, M.; Deckert, M.; Greenberg, A.H.; Bernard, A. CD47 and the 19 kDa Interacting Protein-3 (BNIP3) in T Cell Apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 23915–23921.

- Li, S.S.; Forslöw, A.; Sundqvist, K.-G. Autocrine Regulation of T Cell Motility by Calreticulin-Thrombospondin-1 Interaction. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 654–661.

- Guillon, J.; Petit, C.; Moreau, M.; Toutain, B.; Henry, C.; Roché, H.; Bonichon-Lamichhane, N.; Salmon, J.P.; Lemonnier, J.; Campone, M.; et al. Regulation of Senescence Escape by TSP1 and CD47 Following Chemotherapy Treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 199.

- Isenberg, J.S.; Maxhimer, J.B.; Hyodo, F.; Pendrak, M.L.; Ridnour, L.A.; DeGraff, W.G.; Tsokos, M.; Wink, D.A.; Roberts, D.D. Thrombospondin-1 and CD47 Limit Cell and Tissue Survival of Radiation Injury. Am. J. Pathol. 2008, 173, 1100–1112.

- Soto-Pantoja, D.R.; Ridnour, L.A.; Wink, D.A.; Roberts, D.D. Blockade of CD47 Increases Survival of Mice Exposed to Lethal Total Body Irradiation. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1038.

- Sick, E.; Jeanne, A.; Schneider, C.; Dedieu, S.; Takeda, K.; Martiny, L. CD47 Update: A Multifaceted Actor in the Tumour Microenvironment of Potential Therapeutic Interest. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 167, 1415–1430.

- Isenberg, J.S.; Ridnour, L.A.; Dimitry, J.; Frazier, W.A.; Wink, D.A.; Roberts, D.D. CD47 Is Necessary for Inhibition of Nitric Oxide-Stimulated Vascular Cell Responses by Thrombospondin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 26069–26080.

- Kaur, S.; Martin-Manso, G.; Pendrak, M.L.; Garfield, S.H.; Isenberg, J.S.; Roberts, D.D. Thrombospondin-1 Inhibits VEGF Receptor-2 Signaling by Disrupting Its Association with CD47. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 38923–38932.

- Kaur, S.; Chang, T.; Singh, S.P.; Lim, L.; Mannan, P.; Garfield, S.H.; Pendrak, M.L.; Soto-Pantoja, D.R.; Rosenberg, A.Z.; Jin, S.; et al. CD47 Signaling Regulates the Immunosuppressive Activity of VEGF in T Cells. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 3914–3924.

- Isenberg, J.S.; Martin-Manso, G.; Maxhimer, J.B.; Roberts, D.D. Regulation of Nitric Oxide Signalling by Thrombospondin 1: Implications for Anti-Angiogenic Therapies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 182–194.

- Isenberg, J.S.; Hyodo, F.; Ridnour, L.A.; Shannon, C.S.; Wink, D.A.; Krishna, M.C.; Roberts, D.D. Thrombospondin 1 and Vasoactive Agents Indirectly Alter Tumor Blood Flow. Neoplasia 2008, 10, 886–896.

- Gao, L.; Chen, K.; Gao, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Yang, Y.-G. CD47 Deficiency in Tumor Stroma Promotes Tumor Progression by Enhancing Angiogenesis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 22406–22413.

- Jeanne, A.; Martiny, L.; Dedieu, S. Thrombospondin-Targeting TAX2 Peptide Impairs Tumor Growth in Preclinical Mouse Models of Childhood Neuroblastoma. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 81, 480–488.

- Yue, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, N.; Qi, Z.; Mao, X.; Guo, S.; Li, F.; Guo, Y.; Lin, Y.; et al. Bortezomib-Resistant Multiple Myeloma Patient-Derived Xenograft Is Sensitive to Anti-CD47 Therapy. Leuk. Res. 2022, 122, 106949.

- Cooper, J.; Giancotti, F.G. Integrin Signaling in Cancer: Mechanotransduction, Stemness, Epithelial Plasticity, and Therapeutic Resistance. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 347–367.

- Lindberg, F.P.; Gresham, H.D.; Reinhold, M.I.; Brown, E.J. Integrin-Associated Protein Immunoglobulin Domain Is Necessary for Efficient Vitronectin Bead Binding. J. Cell Biol. 1996, 134, 1313–1322.

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Guo, N.H.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Kaiser, J.; Roberts, D.D. Pro-Adhesive and Chemotactic Activities of Thrombospondin-1 for Breast Carcinoma Cells Are Mediated by alpha3beta1 Integrin and Regulated by Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 and CD98. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 11408–11416.

- Gao, A.G.; Lindberg, F.P.; Dimitry, J.M.; Brown, E.J.; Frazier, W.A. Thrombospondin Modulates Alpha v Beta 3 Function through Integrin-Associated Protein. J. Cell Biol. 1996, 135, 533–544.

- Shahan, T.A.; Fawzi, A.; Bellon, G.; Monboisse, J.C.; Kefalides, N.A. Regulation of Tumor Cell Chemotaxis by Type IV Collagen Is Mediated by a Ca(2+)-Dependent Mechanism Requiring CD47 and the Integrin alpha(V)beta(3). J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 4796–4802.

- Yoshida, H.; Tomiyama, Y.; Ishikawa, J.; Oritani, K.; Matsumura, I.; Shiraga, M.; Yokota, T.; Okajima, Y.; Ogawa, M.; Miyagawa, J.I.; et al. Integrin-Associated protein/CD47 Regulates Motile Activity in Human B-Cell Lines through CDC42. Blood 2000, 96, 234–241.

- Wilson, K.E.; Li, Z.; Kara, M.; Gardner, K.L.; Roberts, D.D. Beta 1 Integrin- and Proteoglycan-Mediated Stimulation of T Lymphoma Cell Adhesion and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling by Thrombospondin-1 and Thrombospondin-1 Peptides. J. Immunol. 1999, 163, 3621–3628.

- Barazi, H.O.; Li, Z.; Cashel, J.A.; Krutzsch, H.C.; Annis, D.S.; Mosher, D.F.; Roberts, D.D. Regulation of Integrin Function by CD47 Ligands. Differential Effects on Alpha Vbeta 3 and Alpha 4beta1 Integrin-Mediated Adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 42859–42866.

- Hermann, P.; Armant, M.; Brown, E.; Rubio, M.; Ishihara, H.; Ulrich, D.; Caspary, R.G.; Lindberg, F.P.; Armitage, R.; Maliszewski, C.; et al. The Vitronectin Receptor and Its Associated CD47 Molecule Mediates Proinflammatory Cytokine Synthesis in Human Monocytes by Interaction with Soluble CD23. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 144, 767–775.

- Armant, M.; Avice, M.N.; Hermann, P.; Rubio, M.; Kiniwa, M.; Delespesse, G.; Sarfati, M. CD47 Ligation Selectively Downregulates Human Interleukin 12 Production. J. Exp. Med. 1999, 190, 1175–1182.

- Avice, M.N.; Rubio, M.; Sergerie, M.; Delespesse, G.; Sarfati, M. CD47 Ligation Selectively Inhibits the Development of Human Naive T Cells into Th1 Effectors. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 4624–4631.

- Barclay, A.N.; Brown, M.H. The SIRP Family of Receptors and Immune Regulation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 6, 457–464.

- Catalán, R.; Orozco-Morales, M.; Hernández-Pedro, N.Y.; Guijosa, A.; Colín-González, A.L.; Ávila-Moreno, F.; Arrieta, O. CD47-SIRPα Axis as a Biomarker and Therapeutic Target in Cancer: Current Perspectives and Future Challenges in Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 9435030.

- Hatherley, D.; Harlos, K.; Dunlop, D.C.; Stuart, D.I.; Barclay, A.N. The Structure of the Macrophage Signal Regulatory Protein α (SIRPα) Inhibitory Receptor Reveals a Binding Face Reminiscent of That Used by T Cell Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 14567–14575.

- Brooke, G.; Holbrook, J.D.; Brown, M.H.; Barclay, A.N. Human Lymphocytes Interact Directly with CD47 through a Novel Member of the Signal Regulatory Protein (SIRP) Family. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 2562–2570.

- Stefanidakis, M.; Newton, G.; Lee, W.Y.; Parkos, C.A.; Luscinskas, F.W. Endothelial CD47 Interaction with SIRPgamma Is Required for Human T-Cell Transendothelial Migration under Shear Flow Conditions in Vitro. Blood 2008, 112, 1280–1289.

- Dehmani, S.; Nerrière-Daguin, V.; Néel, M.; Elain-Duret, N.; Heslan, J.-M.; Belarif, L.; Mary, C.; Thepenier, V.; Biteau, K.; Poirier, N.; et al. SIRPγ-CD47 Interaction Positively Regulates the Activation of Human T Cells in Situation of Chronic Stimulation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 732530.

- Gauttier, V.; Pengam, S.; Durand, J.; Biteau, K.; Mary, C.; Morello, A.; Néel, M.; Porto, G.; Teppaz, G.; Thepenier, V.; et al. Selective SIRPα Blockade Reverses Tumor T Cell Exclusion and Overcomes Cancer Immunotherapy Resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 6109–6123.

- Frazier, W.A.; Gao, A.G.; Dimitry, J.; Chung, J.; Brown, E.J.; Lindberg, F.P.; Linder, M.E. The Thrombospondin Receptor Integrin-Associated Protein (CD47) Functionally Couples to Heterotrimeric Gi. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 8554–8560.

- Zhang, C.; Saunders, A.J. An Emerging Role for Ubiquilin 1 in Regulating Protein Quality Control System and in Disease Pathogenesis. Discov. Med. 2009, 8, 18–22.

- Wu, A.L.; Wang, J.; Zheleznyak, A.; Brown, E.J. Ubiquitin-Related Proteins Regulate Interaction of Vimentin Intermediate Filaments with the Plasma Membrane. Mol. Cell 1999, 4, 619–625.

- N’Diaye, E.-N.; Brown, E.J. The Ubiquitin-Related Protein PLIC-1 Regulates Heterotrimeric G Protein Function through Association with Gbetagamma. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 163, 1157–1165.

- Sick, E.; Boukhari, A.; Deramaudt, T.; Rondé, P.; Bucher, B.; André, P.; Gies, J.-P.; Takeda, K. Activation of CD47 Receptors Causes Proliferation of Human Astrocytoma but Not Normal Astrocytes via an Akt-Dependent Pathway. Glia 2011, 59, 308–319.

- Chung, J.; Gao, A.G.; Frazier, W.A. Thrombspondin Acts via Integrin-Associated Protein to Activate the Platelet Integrin alphaIIbbeta3. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 14740–14746.

- Wang, X.Q.; Lindberg, F.P.; Frazier, W.A. Integrin-Associated Protein Stimulates alpha2beta1-Dependent Chemotaxis via Gi-Mediated Inhibition of Adenylate Cyclase and Extracellular-Regulated Kinases. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 147, 389–400.

- Manna, P.P.; Frazier, W.A. The Mechanism of CD47-Dependent Killing of T Cells: Heterotrimeric Gi-Dependent Inhibition of Protein Kinase A. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 3544–3553.

- Soto-Pantoja, D.R.; Miller, T.W.; Pendrak, M.L.; DeGraff, W.G.; Sullivan, C.; Ridnour, L.A.; Abu-Asab, M.; Wink, D.A.; Tsokos, M.; Roberts, D.D. CD47 Deficiency Confers Cell and Tissue Radioprotection by Activation of Autophagy. Autophagy 2012, 8, 1628–1642.

- Kalas, W.; Swiderek, E.; Switalska, M.; Wietrzyk, J.; Rak, J.; Strzadala, L. Thrombospondin-1 Receptor Mediates Autophagy of RAS-Expressing Cancer Cells and Triggers Tumour Growth Inhibition. Anticancer. Res. 2013, 33, 1429–1438.

More

Information

Subjects:

Pathology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

738

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

10 Nov 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No