Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ahsanullah Unar | -- | 6163 | 2023-09-25 08:10:50 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 6163 | 2023-09-25 08:16:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Unar, A.; Bertolino, L.; Patauner, F.; Gallo, R.; Durante-Mangoni, E. Decoding Sepsis-Induced Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/49584 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Unar A, Bertolino L, Patauner F, Gallo R, Durante-Mangoni E. Decoding Sepsis-Induced Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/49584. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Unar, Ahsanullah, Lorenzo Bertolino, Fabian Patauner, Raffaella Gallo, Emanuele Durante-Mangoni. "Decoding Sepsis-Induced Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/49584 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Unar, A., Bertolino, L., Patauner, F., Gallo, R., & Durante-Mangoni, E. (2023, September 25). Decoding Sepsis-Induced Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/49584

Unar, Ahsanullah, et al. "Decoding Sepsis-Induced Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation." Encyclopedia. Web. 25 September, 2023.

Copy Citation

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a pathological disease that often manifests as a complication in patients with sepsis. Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory response caused by infection and is a major public health concern worldwide.

sepsis

disseminated intravascular coagulation

therapy

corticosteroids

1. Introduction

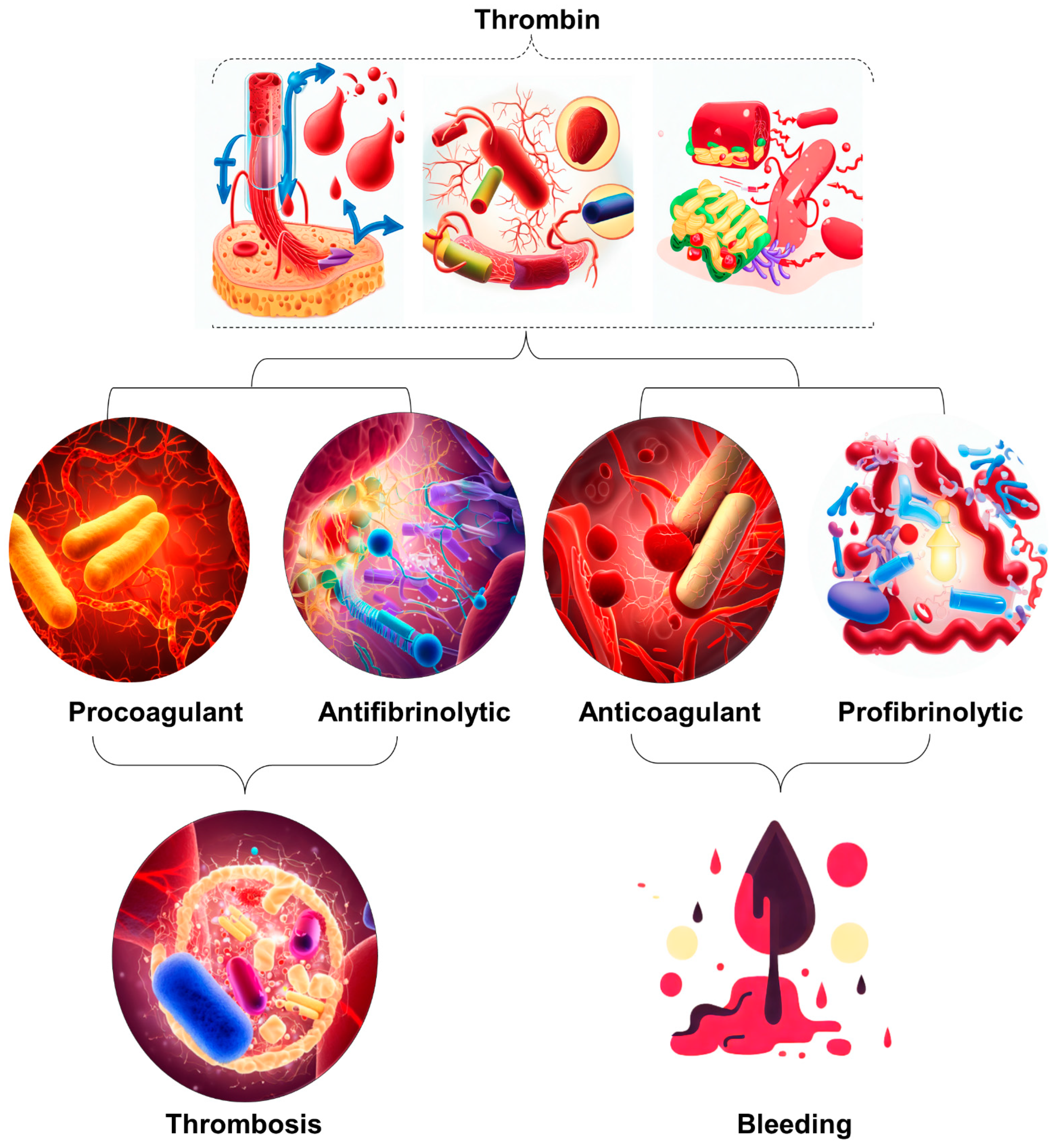

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a pathological disease that often manifests as a complication in patients with sepsis. Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory response caused by infection and is a major public health concern worldwide [1]. To understand the evolution of the sepsis concept, Table 1 provides an overview of the differences between the traditional approach based on systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and the sepsis-3 definition, which emphasizes organ dysfunction or risk of death [1][2][3][4][5][6]. Coagulation disorders that can lead to the development of DIC are often observed in sepsis. DIC is a disease that results in microvascular coagulation, decreased organ perfusion, organ failure, and an increased risk of death. The incidence rate of DIC is estimated at 2.5 cases per 1000 people, with an 8.7% increase over the two decades [1][3]. Sepsis disrupts the blood coagulation process and leads to disruption of hemostasis; however, among these, DIC represents the most serious complication. Approximately 50–70% of patients suffer from DIC. In approximately 35% of cases, it manifests itself overtly. The diagnosis of DIC typically involves the assessment of coagulation markers but lacks sufficient specificity. Therefore, it is crucial to distinguish DIC from diseases characterized by platelet count [7][8]. Unfortunately, several patients who develop thrombocytopenia from a variety of causes are often initially misdiagnosed as having disseminated DIC. This misdiagnosis can result in these patients not receiving the treatment they need. The coagulation process is closely intertwined with the system and is linked to other inflammatory responses [9][10]. The term immune thrombosis refers to the interaction between coagulation and innate immunity [11]. Traditionally, it has been assumed that coagulation activation is triggered by a tissue factor on monocytes and macrophages that is induced by microorganisms and their components, so-called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [12].Tissue factor (TF) is a potent initiator of coagulation [13] and induces proinflammatory responses through the activation of protease-activated receptors (PARs) [13][14]. Phosphatidylserine on the cell membrane has been identified as an important coagulation activator [15]. Apart from these PAMPs, it has also been found that damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released by injured cells, such as B. cell-free DNA histones and high mobility group box one protein (HMGB1), contribute to the initiation of coagulation [9]. Extracellular neutrophil traps (NETs), composed of DNA fibers, nuclear proteins, and antimicrobial peptides, have been found to enhance thrombogenicity [9].In addition to activation of coagulation, suppression of fibrinolysis is an important feature of sepsis DIC. PAI-1 released from damaged endothelial cells inhibits fibrinolysis and leads to the development of a thrombotic phenotype associated with coagulopathy (Figure 1) [16][17].

Figure 1. Illustration of the occurrence of excessive thrombin formation in DIC resulting in either bleeding or thrombosis. The specific outcome is determined by the predominant change disrupting the delicate balance between procoagulant and fibrinolytic effects. The dynamic interaction between procoagulant and fibrinolytic mechanisms in DIC plays a crucial role in determining the clinical manifestations of the disease. Therefore, it is imperative to implement timely and targeted therapeutic strategies to maximize patient outcomes.

Table 1. A Comparative Analysis of Sepsis Definitions: Traditional SIRS-based vs. Sepsis 3 Approach [18].

| Feature | Previous Sepsis Definitions (SIRS-Based) | Sepsis 3 Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Sepsis is SIRS + confirmed or presumed infections * | Sepsis is life-threatening organ dysfunction due to a dysregulated host response to infection |

| Organ Dysfunction Criteria | Based on individual clinical criteria (e.g., temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, WBC count) | Organ dysfunction defined as an increase of 2 or more points in the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score |

| Clinical Criteria | Relatively simple criteria (e.g., T > 38 C or <36 C, p > 90/min, RR > 20/min or PaCO2 < 32 mmHg, WBC > 12 or >10% immature band forms) | qSOFA (HAT) **: Hypotension (SBP ≤ 100 mmHg), Altered mental status (any GCS < 15), Tachypnea (RR ≥ 22) |

| Classification of Severity | Sepsis, Severe Sepsis, Septic Shock | Sepsis, Septic Shock (Severe Sepsis no longer exists) |

| Diagnostic Accuracy | Lack of sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing severe sepsis | Improved predictive validity and accuracy in diagnosing sepsis |

| Use in ICU Patients | SIRS criteria lacked sensitivity for defining sepsis in ICU patients | SOFA score superior to SIRS in predicting mortality in ICU patients |

| Use in Non-ICU Patients | Less accurate in predicting hospital mortality outside the ICU | Similar predictive performance in non-ICU patients |

| Global Applicability | Used globally, but lacks standardization and content validity | Development and validation conducted in high-income countries |

| Prognostic Value | Limited ability to predict patient outcomes and mortality | Enhanced ability to prognosticate patient outcomes and mortality risk |

| Emphasis on Infection Trigger | Inclusion of infection as a crucial component in sepsis diagnosis | Maintains the importance of infection in defining sepsis |

| Endorsement by Professional Orgs. | Various organizations endorsed previous definitions | Not universally endorsed by all organizations |

T > Temperature, p > Pulse Rate, RR > Respiratory Rate, Pa-CO2 > Partial Pressure of Carbon Dioxide (Pa-CO2), WBC > White Blood Cell Count. qSOFA > quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, “HAT” represents the three components of qSOFA: H-Hypotension, A-Altered Mental Status. T–Tachypnea. * Sepsis is characterized by Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) accompanied by confirmed or presumed infections. ** qSOFA is a simplified bedside tool that aids healthcare providers in quickly assessing patients with suspected infection for signs of organ dysfunction. If a patient presents with two or more of the qSOFA criteria, it indicates a higher risk of sepsis-related complications and may prompt further evaluation and early intervention to improve patient outcomes. However, it is important to note that qSOFA is not intended to diagnose sepsis definitively but serves as a screening tool to identify patients who require closer monitoring and additional evaluation for possible sepsis.

2. Comparative Analysis of DIC Diagnosis and Treatment: Eastern vs. Western Approaches

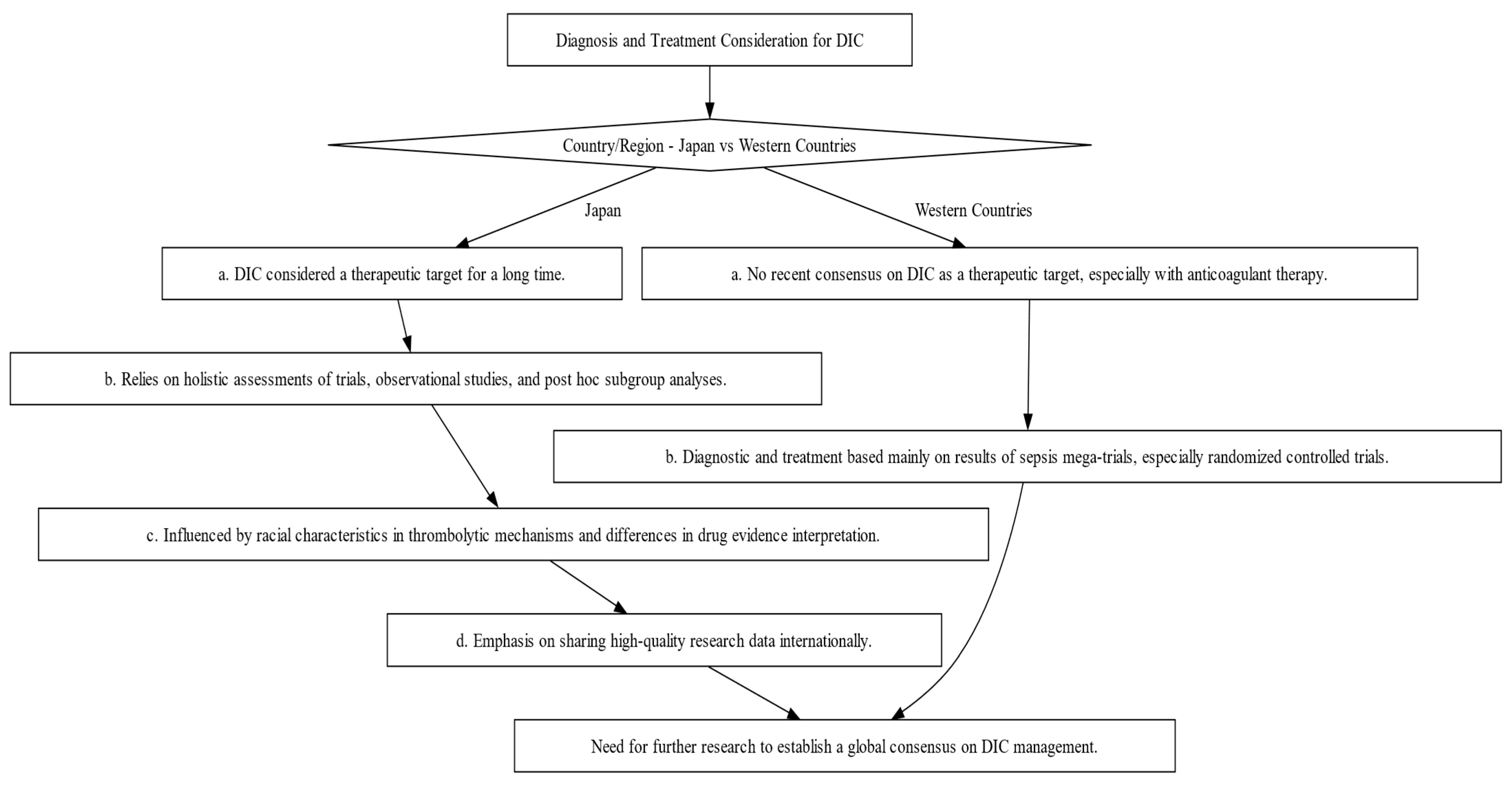

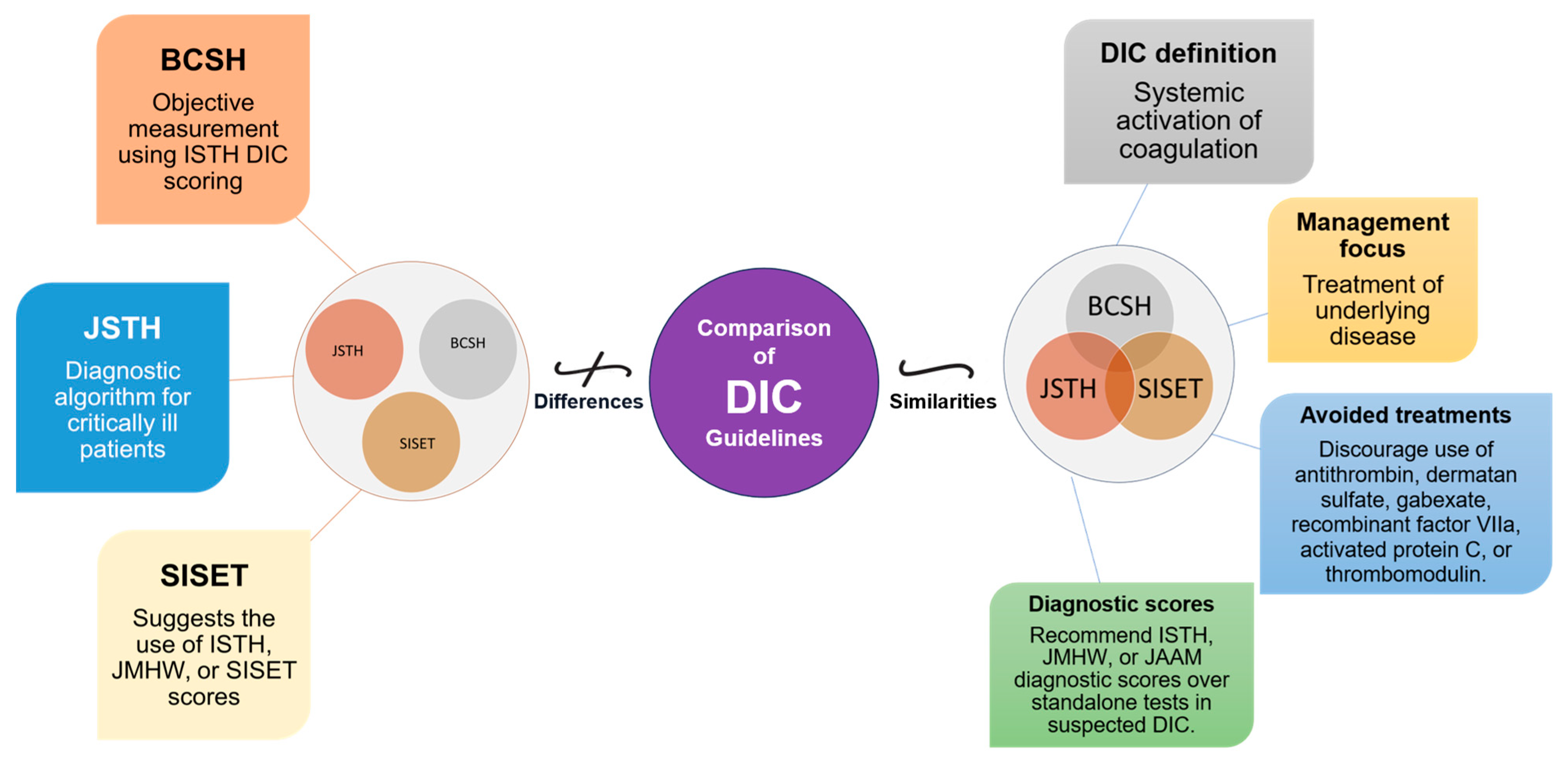

The diagnosis and management of DIC manifest distinct variations between Japan and Western countries (Figure 2). These variations are shaped by multiple factors, including differing understandings of thrombolytic mechanisms and the types of evidence deemed valid for therapeutic decision-making. In Japan, clinicians adopt a holistic approach, integrating a wide array of research methodologies, ranging from clinical trials and subgroup analyses to observational studies, to inform treatment protocols [19][20]. Conversely, Western medical practice primarily relies on large-scale studies that focus on sepsis, often employing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) as the research design [19]. This section will shed light on these distinctions and their implications and as well as highlight the primary commonalities and distinctions in the clinical guidelines for managing DIC as laid out by BCSH (British Committee for Standards in Haematology), JSTH (Japanese Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis), and SISET (Italian Society for Thrombosis and Hemostasis (Figure 3) [19][20][21]. The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) has established specific criteria for the diagnosis of overt DIC, which include parameters such as low platelet count and prolonged prothrombin time. In contrast, Japan introduced an alternative approach in 2006 called the Japanese Society of Acute Medicine (JAAM) criteria, which emphasizes laboratory tests and clinical data for an accurate diagnosis.

Figure 2. Decision-making Flowchart Depicting the Contrasts in Diagnosis and Treatment Approaches for DIC between Japan and Western Countries. This flowchart illustrates the divergent philosophies and methods for DIC diagnosis and treatment, emphasizing the influence of regional factors such as evidence interpretation and trial designs.

Figure 3. Comparative Overview of DIC Guidelines: Commonalities and Distinctions. This figure illustrates the commonalities and distinctions between DIC guidelines from BCSH (British Committee for Standards in Haematology), JSTH (Japanese Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis), and SISET (Italian Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis). Shared principles encompass recognizing DIC as a systemic coagulation activation syndrome with microvascular thrombosis and organ dysfunction, prioritizing treatment of the underlying trigger, and discouraging specific interventions. In suspected DIC cases, all guidelines favor established diagnostic scores (International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH), the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare (JMHW), and the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (JAAM)). Differences include variations in treatment recommendations, the ISTH’s simple scoring system for overt DIC, JAAM’s focus on critically ill patients, SISET’s endorsement of diagnostic scores, and BCSH’s objective measurement using ISTH DIC scoring system, which is closely linked to clinical outcomes.

A comparative study by Gando et al. found that the JAAM criteria have higher sensitivity compared to the ISTH criteria. Sensitivity here means that JAAM criteria are better able to correctly identify DIC cases. In their study, the JAAM criteria diagnosed DIC in 46.8% of cases, while the ISTH criteria identified it in only 18.1%. It is important that all cases identified according to ISTH criteria were also recorded according to JAAM criteria. When looking at 28-day mortality rates, both criteria showed similar results, with 31.8% for JAAM and 30.1% for ISTH [22][23]. This suggests that patients excluded by ISTH criteria may suffer from DIC, highlighting the value of JAAM criteria due to their integrative approach. However, the landscape changed with the introduction of the Sepsis-3 definition, which includes the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) score, making the JAAM criteria somewhat less relevant. In response, a new set of criteria called sepsis-induced coagulopathy (SIC) was developed in 2017 to support early DIC diagnosis in sepsis patients. It considers both sepsis and clotting problems, such as a low platelet count. In diagnosing and managing DIC, physicians rely on laboratory findings, including low platelet count, elevated D-dimers, and abnormal clotting times, alongside clinical assessment [24][25]. These indicators inform the ISTH scoring system for overt DIC diagnosis [2][3]. Key tests include Complete Blood Count (CBC), Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT), Prothrombin Time (PT) assay, fibrinogen, and D-dimer assays. D-dimer and Fibrin Degradation Product (FDP) tests offer robust diagnostic value [4]. A comprehensive DIC panel includes D-dimer and FDP for swift diagnosis and antithrombin for severity assessment and prognosis [24][25][26]. Table 2 provides a detailed comparison of the diagnostic criteria used by the ISTH for both open DIC and SIC and the criteria used by the JAAM for DIC. The criteria are divided into low-risk, medium-risk, and high-risk categories, each of which has a specific rating [21][22][23][27][28][29][30].

Table 2. Comparative Evaluation of Diagnostic Criteria Across ISTH Overt DIC, JAAM DIC, and ISTH SIC Scoring Systems.

| Parameter (Units) | Diagnostic Method | Low-Risk Criteria (Score = 1) | Moderate-Risk Criteria (Score = 2) | High-Risk Criteria (Score = 3) | Interpretative Notes |

| Platelet Count (×10⁹ per L) | ISTH Overt DIC | 50–100 | N/A | <80 or 50% drop in 24 h 1 | Lower counts indicate severe clotting issues |

| JAAM DIC | <50 | N/A | N/A | - | |

| ISTH SIC | 100–150 | <100 | N/A | - | |

| Fibrin Degradation Products (FDP)/D-dimer (μg/mL) | ISTH Overt DIC | N/A | Moderate increase 2 | Strong increase 3 | Elevated levels suggest severe clotting issues |

| JAAM DIC | 10–25 | N/A | ≥25 | - | |

| ISTH SIC | N/A | N/A | N/A | - | |

| Prothrombin Time (PT) (seconds or PT-INR) | ISTH Overt DIC | 1.2–1.4 PT-INR | 3–6 s | ≥6 s | Longer times signify clotting dysfunction |

| JAAM DIC | 1.2–1.4 PT-INR | N/A | >1.4 PT-INR | - | |

| ISTH SIC | N/A | N/A | N/A | - | |

| Fibrinogen Levels (g/mL) | ISTH Overt DIC | N/A | N/A | <100 | Low levels indicate severe coagulation issues |

| JAAM DIC | N/A | N/A | N/A | - | |

| ISTH SIC | N/A | N/A | N/A | - | |

| SIRS Score | ISTH Overt DIC | N/A | N/A | N/A | - |

| JAAM DIC | >3 | N/A | N/A | Elevated scores indicate systemic inflammation | |

| ISTH SIC | N/A | N/A | N/A | - | |

| SOFA Score | ISTH Overt DIC | N/A | N/A | N/A | - |

| JAAM DIC | 1 | N/A | N/A | Score assesses multi-organ dysfunction | |

| ISTH SIC | 1 | ≥2 | N/A | - |

1 A reduction of 50% in platelet count within 24 h is indicative of high risk for DIC as per ISTH guidelines. 2 A ‘Moderate increase’ in FDP/D-dimer generally refers to a 10–25% increase from baseline levels. 3 A ‘Strong increase’ in FDP/D-dimer generally refers to an increase greater than 25% from baseline levels. DIC: Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation, a severe disorder causing abnormal blood clotting. SIC: Sepsis-Induced Coagulopathy, a condition where blood clotting is triggered by infection. JAAM: Methodology developed by the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine. ISTH: Methodology established by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. PT-INR: Prothrombin Time to International Normalized Ratio, a standardized measure of blood clotting time. Measured in seconds or as a PT to International Normalized Ratio (PT-INR). SIRS: Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, an indicator of systemic inflammation. SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, an evaluation of multi-organ functionality. Platelet Count: Measured in ×109 per liter (L); D-dimer Levels: Measured in micrograms per milliliter (μg/mL); Fibrinogen Levels: Measured in grams per milliliter (g/mL); “Score = 1” denotes Low-Risk Criteria, “Score = 2” denotes Moderate-Risk Criteria, and “Score = 3” denotes High-Risk Criteria. ‘N/A’ signifies that the criteria are not applicable under the particular diagnostic method.

Managing DIC is a multifaceted challenge, and the primary goal is to address the underlying infection. However, there’s limited solid evidence supporting the use of anticoagulant therapy alongside antibiotics and source control. Several large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving different anticoagulants have failed to provide conclusive evidence of their effectiveness. Nonetheless, guidelines recommend anticoagulant therapy for patients with severe sepsis-associated DIC, particularly if they have coagulation problems. These recommendations have been validated by the ISTH DIC Scientific Standardization Committee [1][21][27][31]. A hypothesis known as the “East Asian paradox” suggests that unique genetic or environmental factors specific to East Asian populations might contribute to the observed differences in DIC diagnosis and management. The choice of anticoagulant therapy for sepsis-induced DIC depends on the condition’s severity and the specific diagnostic criteria in use. Japanese researchers are encouraged to share their clinical research data internationally to improve the understanding of DIC and its management [30]. Overall, there is a major discrepancy between diagnostic and treatment options in Japan and Western countries, and further research is needed to establish an international consensus on DIC as a therapeutic target. Investigations should also focus on the coagulofibrinolytic system in sepsis and the impact of racial characteristics on thrombolytic mechanisms.

3. Can Sepsis-Induced DIC Patients Benefit from Corticosteroids?

Corticosteroids, commonly referred to as CS, continue to be a subject of debate within the community regarding their use in treating sepsis, septic shock, and DIC. There is no consensus due to conflicting results from studies. Gibbison et al. [32] Annane et al. [33] Salluh et al. [34] share perceptions about the possible advantages of CS in addressing sepsis-induced DIC. However, they also highlight the need for research considering the nature of the current evidence. There is obviously a need for more high-quality randomized controlled trials based on these two comprehensive reviews, reflecting the existing uncertainty in this area. In contrast, Rochwerg et al. [35] reported that sepsis patients treated with CS may have reduced mortality. However, they also noted the low reliability of these results, consistent with the urge for more detailed investigation expressed in earlier studies. In addition, according to Gibbison et al. [32], there is quite a positive response to CS on coagulation factors. Despite the possibility of a positive result, the researchers emphasized the experimental nature of their findings and the need for future studies to confirm them. A positive perspective was provided by Gazzaniga et al. [36], who suggested a potential reduction in the risk of SIC with the use of CS. However, like the other studies, they acknowledged the moderate quality of their evidence, further underscoring the need for higher-quality studies. Finally, Ni et al. [37] and Liang et al. [38] found potential benefits of CS in reducing mortality in patients with septic shock and improving outcomes in patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy. Despite these encouraging results, both studies recommended further investigation and careful interpretation of the results due to possible confounding factors.

Considering these diverse studies, it becomes clear that while there are hints of potential benefits associated with CS in sepsis and septic shock treatment, the current evidence is still inconclusive, with questions about the certainty and quality of the findings. The consensus among all authors is the pressing need for further rigorous and high-quality research to substantiate these preliminary findings, assess the potential risks and benefits more robustly, and clarify the role of CS in the treatment of sepsis and sepsis-induced coagulopathy.

Moreover, future research should consider the factors that might explain the discrepancies in these studies’ results, such as variations in dosage, timing of administration, patient population, patient endotypes, and study design (Table 3). Until a clear consensus appears from more definitive research, clinicians should make decisions on the use of CS on a case-by-case basis, considering each patient’s individual circumstances, the potential benefits and risks of corticosteroid use, and the existing guidelines.

Table 3. Summary of Therapies for Sepsis-Related DIC.

| Therapy | Mechanism of Action | Dosage and Administration | Efficacy | Adverse Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfractionated Heparin (UFH) | Anticoagulant | Dosage: Based on weight, typically 80 units/kg bolus followed by 18 units/kg/hr infusion | Limited high-quality evidence for use in sepsis-related DIC. Small trials show potential benefits in early-stage sepsis patients but not necessarily in sepsis DIC patients | Bleeding risk | [19][39][40][41] |

| Recombinant Soluble TM (rsTM) | Alleviates DIC and reduces mortality | Dosage: Varies, typically administered intravenously | More effective than UFH in alleviating DIC and reducing mortality in infectious DIC patients | NS * | [39][40][41][42][43] |

| Activated Protein C (APC) | Anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory agent; degrades extracellular histones | Dosage: Varies, typically administered intravenously | No significant difference in response rates compared to UFH for DIC; reduces bleeding risk and mortality | Bleeding risk | [44][45][46][47][48][49] |

| High-dose Antithrombin (AT) | Reduces mortality in DIC patients without significant bleeding events | Dosage: Varies, typically administered intravenously | No reduction in mortality in sepsis patients; increases bleeding risk | Increased bleeding risk | [44][45][49][50] |

| Corticosteroids | Unclear mechanism; potential benefits in sepsis-induced DIC | Dosage: Varies depending on the specific corticosteroid used and patient condition | Contrasting findings, inconclusive evidence. Some studies suggest potential benefits, while others show no significant impact or potential harm | Potential adverse effects: increased risk of infection, metabolic disturbances | [32][33][34][35][36][38][51] |

| Thrombomodulin alfa (rTM) | Binds to thrombin, activates protein C, downregulates coagulation | Dosage: Varies, typically administered intravenously | Reduction in overall mortality rates, minimized bleeding complications | NS * | [8][52][53] |

| Vitamin C | Potential antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticoagulant properties | Dosage: Varies, typically administered intravenously | Inconclusive evidence. Some studies show potential benefits in certain parameters, while others show no significant impact or potential harm | NS * | [54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61] |

| Fibrinolytic Therapy | Reduces clot formation, improves organ perfusion | Dosage: Varies depending on the specific fibrinolytic agent used | Impact on clinical outcomes inconclusive; some studies show improvements in coagulation parameters, while others show no significant effect | Bleeding risk | [62][63][64][65][66][67] |

| Platelet Transfusion | Controversial; potential benefits in severe thrombocytopenia or active bleeding | Dosage: Varies depending on the patient’s platelet count and clinical condition | Evidence supporting efficacy is sparse; conflicting recommendations | Potential adverse effects: bleeding complications | [68][69][70][71][72][73] |

| Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (G-CSF) | Stimulates production and mobilization of neutrophils | Dosage: Varies, typically administered subcutaneously or intravenously | Potential benefits in improving coagulation parameters | NS * | [74][75][76][77] |

| Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF) | Acts on neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages | Dosage: Varies, typically administered subcutaneously or intravenously | Impact on sepsis-induced DIC not yet clearly defined | NS | [74][75] |

| Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) | Improves coagulation abnormalities, shows a trend toward decreased mortality in sepsis-induced coagulopathy patients | Dosage: Varies, typically administered intravenously | Improved coagulation abnormalities, reduced DIC duration, potential decrease in mortality | NS | [53] |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Immunomodulatory effects through cytokine secretion | Dosage: Varies, typically administered intravenously | Promising results in preclinical studies, potential to improve outcomes in sepsis-induced DIC | NS * | [78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87] |

* NS stands for Not Specified.

4. Vitamin C in Sepsis and DIC: Promise or Paradox?

The investigation and discussion of vitamin C’s role and benefit in sepsis and DIC treatment has attracted significant medical attention. The putative antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticoagulant properties of vitamin C point to its likely benefits in mitigating organ failure and death rates among people afflicted with these ailments [56][57][58]. However, the existing body of scientific literature presents a multifaceted and contradictory image, emphasizing the need for further research. According to a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by researchers [59], the administration of vitamin C did not provide a statistically significant reduction in the mortality rate, length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU), or duration of mechanical breathing among patients with sepsis. Nevertheless, the study showed a discernible inclination toward diminishing the length of vasopressor medication, hence implying that vitamin C may influence the disease’s progression. A recent scientific publication [61] highlighted the possible benefits of vitamin C in the treatment of sepsis, especially focusing on its antioxidant properties and ability to regulate the immunological response. Nevertheless, the authors also placed significant emphasis on the equivocal nature of the existing data and advocated for more studies to ascertain the most effective dosage and timing of vitamin C delivery in individuals with sepsis [61]. Research conducted on the use of high-dose vitamin C (HDVC) therapy in the treatment of sepsis and DIC has shown varied outcomes. A comprehensive investigation revealed that the administration of intravenous vitamin C (IVVC) resulted in a notable enhancement of the delta Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score and a decrease in the duration of vasopressor utilization among individuals diagnosed with sepsis or septic shock. However, no significant correlation was observed between the use of IVVC and a reduction in short-term death rates [57]. Nevertheless, the Vitamin C Therapy for Routine Care in Septic Shock (ViCTOR) trial concluded that the intravenous administration of a regimen consisting of vitamin C, thiamine, and hydrocortisone did not lead to a significant decrease in overall mortality in patients afflicted with septic shock. However, it was noted that the time needed to reverse the onset of septic shock was markedly reduced in the patient group that received this combination therapy [60]. These results were consistent with recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that also reported no mortality benefit with combination therapy [88][89][90][91][92][93]. Another study revealed an intriguing finding. It showed that adult patients dealing with sepsis and undergoing vasopressor therapy within the ICU, when treated with intravenous vitamin C, faced an increased risk. In contrast to those who were administered a placebo, those who received active treatment had an increased probability of experiencing either fatality or persistent organ failure. The heightened risk endured for a substantial duration, namely, until the 28th day following the initiation of the therapy [54]. The divergent results highlight the intricate nature of the involvement of vitamin C in the treatment of sepsis and DIC. While several studies have shown potential advantages, others have discovered no substantial effect or even possible negative consequences [54][55]. This underscores the need for more rigorous, randomized, controlled studies to clarify the therapeutic efficacy of vitamin C in these specific disorders. It is advisable for clinicians to use prudence when considering administering vitamin C for sepsis treatment and DIC, pending the availability of further conclusive data. These findings are significant for researchers in recognizing the complex nature of vitamin C’s role in sepsis. Consequently, there is a need for studies that not only examine its influence on death rates and organ dysfunction but also delve into its impact on the development of the disease and the quality of life experienced by patients. It is important to make efforts to standardize dosage regimens to improve the effectiveness of treatment (Table 3).

In short, the current corpus of literature provides a nuanced and incongruous portrayal of the involvement of vitamin C in the treatment of sepsis and DIC. The continuous discourse among academics and doctors highlights the divergent findings, hence emphasizing the necessity for more exploration. Based on the available information, healthcare professionals are recommended to exercise prudence when considering the administration of vitamin C in cases of sepsis and DIC. The determination of whether to use this intervention should be based on the specific attributes of each patient and the ongoing accumulation of scientific knowledge in this area. The intricacy of biological systems and the difficulties in converting possible therapeutic pathways into practical therapies are highlighted by this argument, particularly for preclinical readers.

5. Fibrinolytic Therapy in Sepsis-Induced DIC: A Potential Game-Changer?

The investigation of fibrinolytic treatment, particularly the use of fibrinolytic drugs such as tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), is a subject of research in the context of sepsis-induced DIC. While the administration of fibrinolytic treatment has a potential hazard of inducing bleeding, it also offers promising advantages by mitigating clot formation and enhancing organ perfusion. Numerous investigations have been conducted to examine the use of fibrinolytic medicines in DIC generated by sepsis. Schouten et al. [66] studied the administration of tPA in a baboon model of DIC induced by sepsis. The authors noted that the administration of tPA resulted in an amplification of fibrinolysis, a reduction in microvascular thrombosis, and an improvement in organ perfusion [66]. The authors [65][67] assessed the use of low-dose tPA in patients who developed DIC due to sepsis. Improvements in coagulation abnormalities were observed because of how to manage low-dose tPA treatment in patients with DIC induced by sepsis, as specified by the study results. The observed enhancements included a reduction in the levels of fibrin degradation products and an augmentation in platelet counts. Significantly, the administration of low-dose tPA did not yield any considerable complications related to bleeding. However, it is imperative to recognize that the application of fibrinolytic therapy in sepsis-induced DIC remains a topic of debate due to the simultaneous risk of hemorrhage. Achieving a delicate equilibrium between the inherent hazards associated with bleeding problems and the prospective advantages necessitates prudent patient selection and diligent monitoring.

In the realm of DIC triggered by sepsis, a thorough examination was undertaken by numerous esteemed researchers. This comprehensive review sought to analyze the existing information pertaining to fibrinolytic treatment [62][63][64][65]. In the realm of scholarly inquiry, a group of diligent researchers undertook a recent systematic analysis to meticulously scrutinize the existing data pertaining to the utilization of fibrinolytic treatment in instances characterized by DIC provoked by sepsis. The findings of the analysis suggest that although fibrinolytic therapy may exhibit improvements in certain laboratory markers linked to coagulation and fibrinolysis, its impact on clinical endpoints, such as mortality, remains inconclusive [62][63][64][65]. The necessity for further study is posited by the authors to ascertain the efficacy of fibrinolytic treatment in augmenting patient outcomes in instances of sepsis-induced DIC. Further investigation is warranted concerning the utilization of fibrinolytic therapy, specifically tPA, in the setting of DIC precipitated by sepsis. Despite the potential for bleeding, the administration of fibrinolytic therapy possesses the capability to attenuate the formation of blood clots and augment the perfusion of vital organs. Favorable effects on fibrinolysis and coagulation problems have been associated with the use of fibrinolytic drugs, as indicated by previous research. At present, the definitive impact of these agents on clinical outcomes remains to be conclusively determined. The optimization of fibrinolytic therapy for sepsis-induced DIC necessitates additional inquiry (Table 3).

6. Platelet Transfusion in Sepsis-Induced DIC: Navigating Controversy and Conflicting Evidence

Therapeutic decision-making can be obscured by contradictory advice within the extensive range of guidelines. In accordance with certain recommendations, it is advisable to consider the possibility of platelet transfusion for patients who are afflicted with sepsis-induced DIC and manifest severe thrombocytopenia or are currently undergoing active bleeding [71]. However, it is vital to recognize the lack of evidence on the effectiveness of platelet transfusion in this context. The existing body of research relies on expert opinion rather than robust scientific trials. A notable investigation in the same domain of the TOPPS trial was conducted by Estcourt et al. [69]. The study’s objective was to evaluate the impact of platelet transfusion on the mortality rate among critically sick patients with thrombocytopenia. The research findings indicated that the administration of platelet transfusion did not have any statistically significant effects on reducing death rates or enhancing patient outcomes [69]. A further investigation was conducted, wherein attention was directed toward individuals suffering from septic shock and DIC [68]. This study’s main objective was to assess the potential association between platelet transfusion and mortality. In congruence with the TOPPS trial, this study demonstrated a lack of mortality reduction in relation to platelet transfusions [68].

This narrative is confirmed by the study conducted by He et al. [70] and Yatabe et al. [72]. The results of their study stipulate that the administration of platelet transfusion did not lead to a reduction in mortality rates among people diagnosed with sepsis. Conversely, it is plausible that this could reduce the duration of stay in the intensive care unit and the hospital, suggesting the potential for unfavorable outcomes [70][72]. In total, the tests collectively demonstrate the lack of empirical evidence of the effectiveness of platelet transfusion in cases of sepsis-induced DIC. Presenting the innovative outlook, Syed Muzaffar et al. offer a contrasting perspective to the studies [73]. The focal point of their research lies in the examination of the pivotal role played by coagulation disorder in the development of sepsis, thereby illuminating the range of coagulopathy induced by sepsis. A more individualized strategy for patient care can be enabled through the proposed triad of coagulation profiles utilizing the Coagulation Index (CI), as put forth by the authors. The authors also underscored the limitations of conventional coagulation assays (CCAs) and drew attention to the utility of thromboelastography (TEG) in the assessment of coagulation profiles [94][95]. The decision to administer platelet transfusion for sepsis-induced DIC should depend on certain contextual factors, considering the patient’s clinical condition, bleeding tendency, and overall trade-off between the advantages and disadvantages of platelet transfusion. The importance of close monitoring of platelet counts and clinical indications in making this decision cannot be overstated. While some guidelines suggest giving platelet transfusion for severe thrombocytopenia or active bleeding, there is also research available, such as the TOPPS test [69] and the study by Andrew et al. [68], that does not demonstrate a significant reduction in mortality or improvement in outcomes from platelet transfusions in this scenario.

Valuable contributions to the existing knowledge of platelet transfusions and coagulation patterns in individuals with sepsis are made by the research conducted by He et al. [70] and Muzaffar et al. [73]. The significance of their study lies in the emphasis on the necessity of implementing meticulous randomized controlled trials and pursuing additional research endeavors to acquire a more comprehensive comprehension of the intricate involvement of platelet transfusion in sepsis-induced DIC. Efforts in future research should be directed toward the identification of distinct subpopulations of patients who may potentially derive advantages from platelet transfusion. Furthermore, the evaluation of their influence on clinical outcomes, encompassing mortality rates and the incidence of hemorrhagic complications, should be undertaken (Table 3).

The ongoing debate and uncertainty surrounding the role of platelet transfusion in the context of sepsis-induced DIC can be attributed to conflicting research findings and divergent viewpoints among experts. There is an ongoing debate within the medical community regarding the pressing necessity for comprehensive research aimed at enhancing the comprehension and expediting the application of clinical therapies in a streamlined fashion. The administration of platelet transfusion in sepsis-induced DIC is currently the subject of a lively debate. This debate stems from the absence of compelling evidence highlighting a noteworthy decrease in mortality rates or enhancement in clinical outcomes linked to this intervention [68][69][70]. Within the realm of clinical decision-making, the utmost significance lies in the prioritization of a customized approach, which is contingent upon meticulous monitoring and diligent evaluation of the unique clinical trajectory exhibited by each patient. To formulate personalized recommendations that align with the specific circumstances of each patient, physicians are required to meticulously assess and modify the intricate equilibrium between potential hazards and expected advantages associated with a transfusion. Valuable insight into the complex elements of the coagulopathy associated with sepsis has been provided by recent developments in scientific studies. The findings of this study lend support to the concept that a uniform treatment strategy may not be the most advantageous but rather emphasize the importance of customizing medical interventions to suit the unique characteristics of each patient (Table 3). In this context, the significance of TEG becomes apparent, as exemplified by its noteworthy application as a diagnostic instrument [73]. Considering the existing dearth of definitive and all-encompassing data, it is important for medical practitioners to exercise judiciousness in contemplating the utilization of platelet transfusion for managing sepsis-induced DIC.

7. Immunomodulatory Therapy: G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, MSCs in Sepsis, DIC, and Their Implications for Clinical Practice & Severe COVID-19

IMT in the context of sepsis-induced DIC is currently an area of active research [74][96]. Various agents, including granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), have been investigated for their potential role in sepsis-induced DIC [97][98]. Nevertheless, the precise elucidation of their specific influence on sepsis-induced DIC remains to be definitively established [97][98]. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), a hematological growth factor, stimulates the production and mobilization of neutrophils. Conversely, it is worth noting that granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) exerts its influence on both neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages [99]. The drugs under consideration have been the focal point of scientific inquiry, with the objective of examining their capacity to enhance immune functionality and enhance outcomes in instances of DIC precipitated by sepsis [74][75]. The impact of G-CSF treatment on individuals diagnosed with sepsis and DIC was examined by the authors [76][77]. The study’s findings elucidated that the administration of G-CSF led to a noteworthy increase in neutrophil counts and amelioration of coagulation parameters in individuals afflicted with sepsis-induced DIC [76][77]. In the therapeutic management of DIC induced by sepsis, IFN-γ, an immunomodulatory drug, has exhibited promising potential. The impact of IFN-γ treatment on patients with sepsis-induced DIC was examined by Iba T. et al. [53] in their study. The study’s findings revealed that the administration of IFN-γ yielded enhancements in coagulation abnormalities, a decrease in the duration of DIC, and a potential decline in fatality rates [53]. However, further inquiry is imperative to attain a holistic understanding of the role played by immunomodulatory drugs in the context of DIC induced by sepsis. Included in this analysis are the exploration of the mechanisms of action, the determination of the best dosage, the identification of the ideal timing for administration, and the refinement of the criteria for selecting patients who may potentially derive therapeutic benefits from such treatment. Conducting randomized controlled studies [6][8][53][72][99][100][101][102][103] is imperative for assessing the effectiveness, safety, and clinical outcomes associated with the utilization of immunomodulatory drugs in this specific context.

Significant interest has been generated in the treatment of sepsis, transplant medicine, and autoimmune diseases through the utilization of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapy. Although the precise cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying MSC-mediated immunomodulation have not yet been fully elucidated, preclinical studies have demonstrated promising results. The immunomodulatory effects of MSCs are exerted via the secretion of cytokines, a process that can be influenced by both the local microenvironment and inflammatory cytokines [78][79].

Additionally, even apoptotic, metabolically inactivated, or fragmented MSCs possess immunomodulatory potential [79][104]. However, the lack of standardization in the isolation, culture, and characterization of MSCs complicates data comparison. MSCs can be derived from various adult and neonatal tissues, each exhibiting unique features in vitro and in vivo [79][80][81] Notably, freshly thawed MSCs appear to have reduced immunomodulatory capacity compared to continuously cultured MSCs [105]. The local microenvironment plays a critical role in shaping MSC-mediated immunomodulation, further adding to its complexity [82][83]. MSCs exert their immunomodulatory effects through a combination of cell contact-dependent mechanisms and the release of soluble factors [79][83][84][85][106][107][108][109][110][111]. MSCs have a significant impact on various immune cells, particularly anti-inflammatory monocytes/macrophages and regulatory T cells (Tregs) [84][85][86]. Interestingly, MSC viability does not appear to be a prerequisite for some of their immunomodulatory effects, as apoptotic MSCs have demonstrated beneficial effects in animal models [112]. Exploring the use of dead or fragmented MSCs may provide more predictable immunomodulatory effects and facilitate better comparison across studies [112].

A case report by Galic et al. presented the successful management of a 14-month-old [92]. The treatment included a combination of antibiotics, plasmapheresis, dialysis, methylprednisolone, mycophenolate mofetil, and eculizumab [87]. Eculizumab therapy was considered in rare cases of sepsis with massive complement consumption after resolving life-threatening multiorgan failure [87]. These studies and reports have important implications for future clinical practice. IMT, including the use of G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, and MSCs, shows promise in improving outcomes in sepsis-induced DIC. However, further research is needed to determine the optimal use, dosing, timing, and impact on clinical outcomes of these therapies [8][53][72][75][78][80][81][82][98][99][100][101][103][104][107][111][113][114][115][116][117][118][119][120][121][122][123][124][125]. The need for cautious administration and withdrawal of the drug is underscored by the potential utilization of eculizumab in instances of sepsis accompanied by complement consumption. In addition, the investigation of extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSC-EVs) as a therapy without the need for cell transplantation presents a hopeful alternative to treatments based on MSCs [87].

By elucidating the intricate relationship between severe COVID-19 and sepsis, which arises from viral infection, one can glean profound insights into the nature of the disease and subsequently enhance the trajectory of future investigations pertaining to therapeutic interventions and preventive strategies [126]. Consideration should be given to the inclusion of IMT in the treatment regimen for severe cases of COVID-19 in conjunction with etiological and supportive interventions [126][127]. The primary objective in the context of COVID-19 immunotherapy should revolve around the mitigation of exaggerated inflammatory responses while simultaneously preserving a controlled level of inflammation and facilitating the restoration of profound immunosuppression [126][127]. In severe cases of COVID-19, it is imperative to conduct additional research to substantiate the safety, efficacy, timing, and dosing of IMT (Table 3) [126].

In conclusion, IMT and MSC-based treatments hold promise for improving outcomes in sepsis-induced DIC and other conditions. However, further research is necessary to fully understand their mechanisms of action, optimize their use in clinical practice, and ensure their safety and efficacy. The exploration of MSC-EVs as a cell-free therapy and the consideration of sepsis-like features in severe COVID-19 provide valuable insights for future studies and therapeutic developments.

References

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810.

- Tsantes, A.G.; Parastatidou, S.; Tsantes, E.A.; Bonova, E.; Tsante, K.A.; Mantzios, P.G.; Vaiopoulos, A.G.; Tsalas, S.; Konstantinidi, A.; Houhoula, D. Sepsis-Induced Coagulopathy: An Update on Pathophysiology, Biomarkers, and Current Guidelines. Life 2023, 13, 350.

- Giustozzi, M.; Ehrlinder, H.; Bongiovanni, D.; Borovac, J.A.; Guerreiro, R.A.; Gąsecka, A.; Papakonstantinou, P.E.; Parker, W.A.E. Coagulopathy and Sepsis: Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations and Treatment. Blood Rev. 2021, 50, 100864.

- Martin, G.S.; Mannino, D.M.; Eaton, S.; Moss, M. The Epidemiology of Sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1546–1554.

- Iba, T.; Di Nisio, M.; Thachil, J.; Wada, H.; Asakura, H.; Sato, K.; Saitoh, D. A Proposal of the Modification of Japanese Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (JSTH) Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) Diagnostic Criteria for Sepsis-Associated DIC. J. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2018, 24, 439–445.

- Iba, T.; Umemura, Y.; Watanabe, E.; Wada, T.; Hayashida, K.; Kushimoto, S. Diagnosis of Sepsis-induced Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation and Coagulopathy. J. Acute Med. Surg. 2019, 6, 223–232.

- Wheeler, A.P.; Bernard, G.R. Treating Patients with Severe Sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 207–214.

- Iba, T.; Watanabe, E.; Umemura, Y.; Wada, T.; Hayashida, K.; Kushimoto, S.; Japanese Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guideline Working Group for Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation; Wada, H. Sepsis-Associated Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation and Its Differential Diagnoses. J. Intensive Care 2019, 7, 32.

- Iba, T.; Levy, J.H. Haemostasis Inflammation and Thrombosis: Roles of Neutrophils, Platelets and Endothelial Cells and Their Interactions in Thrombus Formation during Sepsis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 16, 231–241.

- Semeraro, N.; Ammollo, C.T.; Semeraro, F.; Colucci, M. Coagulopathy of Acute Sepsis. In Proceedings of the Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis; Thieme Medical Publishers: Stuttgart, Germany, 2015; Volume 41, pp. 650–658.

- Engelmann, B.; Massberg, S. Thrombosis as an Intravascular Effector of Innate Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 34–45.

- Corrigan, J.J., Jr.; Ray, W.L.; May, N. Changes in the Blood Coagulation System Associated with Septicemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1968, 279, 851–856.

- Østerud, B.; Bjørklid, E. The Tissue Factor Pathway in Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. In Proceedings of the Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis; Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc.: Stuttgart, Germany, 2001; Volume 27, pp. 605–618.

- Nieman, M.T. Protease-Activated Receptors in Hemostasis. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2016, 128, 169–177.

- Ma, R.; Xie, R.; Yu, C.; Si, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, L.; Yao, Z.; Fang, S.; Chen, H.; Novakovic, V. Phosphatidylserine-Mediated Platelet Clearance by Endothelium Decreases Platelet Aggregates and Procoagulant Activity in Sepsis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4978.

- Gando, S.; Levi, M.; Toh, C.-H. Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. J. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 1–16.

- Levi, M.; van der Poll, T. Coagulation and Sepsis. Thromb. Res. 2017, 149, 38–44.

- Chris Nickson Sepsis Definitions and Diagnosis. Available online: https://litfl.com/sepsis-definitions-and-diagnosis/ (accessed on 3 November 2020).

- Wada, H.; Thachil, J.; Di Nisio, M.; Mathew, P.; Kurosawa, S.; Gando, S.; Kim, H.K.; Nielsen, J.D.; Dempfle, C.; Levi, M. Guidance for Diagnosis and Treatment of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation from Harmonization of the Recommendations from Three Guidelines. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 11, 761–767.

- Di Nisio, M.; Baudo, F.; Cosmi, B.; D’Angelo, A.; De Gasperi, A.; Malato, A.; Schiavoni, M.; Squizzato, A. Diagnosis and Treatment of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: Guidelines of the Italian Society for Haemostasis and Thrombosis (SISET). J. Thromb. Res. 2012, 129, e177–e184.

- Asakura, H.; Takahashi, H.; Uchiyama, T.; Eguchi, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Kawasugi, K.; Madoiwa, S.; Wada, H. Proposal for New Diagnostic Criteria for DIC from the Japanese Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. Thromb. J. 2016, 14, 42.

- Gando, S.; Wada, H.; Thachil, J.; Scientific, T. Differentiating Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) with the Fibrinolytic Phenotype from Coagulopathy of Trauma and Acute Coagulopathy of Trauma-Shock (COT/ACOTS). J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 11, 826–835.

- Gando, S.; Hayakawa, M. Pathophysiology of Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy and Management of Critical Bleeding Requiring Massive Transfusion. In Proceedings of the Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis; Thieme Medical Publishers: Stuttgart, Germany, 2015; pp. 155–165.

- Yu, M.; Nardella, A.; Pechet, L. Screening Tests of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: Guidelines for Rapid and Specific Laboratory Diagnosis. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 28, 1777–1780.

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation—DIC. Choose the Right Test. Available online: https://arupconsult.com/content/disseminated-intravascular-coagulation (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC). Causes & Symptoms. Available online: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21836-disseminated-intravascular-coagulation-dic (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Unar, A.; Bertolino, L.; Patauner, F.; Gallo, R.; Durante-Mangoni, E. Pathophysiology of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation in Sepsis: A Clinically Focused Overview. Cells 2023, 12, 2120.

- Iba, T.; Di Nisio, M.; Levy, J.H.; Kitamura, N.; Thachil, J. New Criteria for Sepsis-Induced Coagulopathy (SIC) Following the Revised Sepsis Definition: A Retrospective Analysis of a Nationwide Survey. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017046.

- Gando, S.; Iba, T.; Eguchi, Y.; Ohtomo, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Koseki, K.; Mayumi, T.; Murata, A.; Ikeda, T.; Ishikura, H. A Multicenter, Prospective Validation of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation Diagnostic Criteria for Critically Ill Patients: Comparing Current Criteria. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 625–631.

- Ushio, N.; Wada, T.; Ono, Y.; Yamakawa, K. Sepsis-induced Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: An International Estrangement of Disease Concept. Acute Med. Surg. 2023, 10, e00843.

- Iba, T.; Helms, J.; Connors, J.M.; Levy, J.H. The Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Sepsis-Associated Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. J. Intensive Care 2023, 11, 24.

- Gibbison, B.; López-López, J.A.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Miller, T.; Angelini, G.D.; Lightman, S.L.; Annane, D. Corticosteroids in Septic Shock: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Crit. Care 2017, 21, 78.

- Annane, D.; Bellissant, E.; Bollaert, P.E.; Briegel, J.; Keh, D.; Kupfer, Y. Corticosteroids for Treating Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. J. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2004, 1, 7.

- Salluh, J.I.F.; Povoa, P. Corticosteroids in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Concise Review. J. Shock. 2017, 47, 47–51.

- Rochwerg, B.; Oczkowski, S.J.; Siemieniuk, R.A.C.; Agoritsas, T.; Belley-Cote, E.; D’Aragon, F.; Duan, E.; English, S.; Gossack-Keenan, K.; Alghuroba, M. Corticosteroids in Sepsis: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 1411–1420.

- Gazzaniga, G.; Tavecchia, G.A.; Bravi, F.; Scavelli, F.; Travi, G.; Campo, G.; Vandenbriele, C.; Tritschler, T.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Murthy, S. The Effect of Antithrombotic Treatment on Mortality in Patients with Acute Infection: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. J. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 383, 75–81.

- Ni, Y.-N.; Liu, Y.-M.; Wang, Y.-W.; Liang, B.-M.; Liang, Z.-A. Can Corticosteroids Reduce the Mortality of Patients with Severe Sepsis? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 1657–1664.

- Liang, H.; Song, H.; Zhai, R.; Song, G.; Li, H.; Ding, X.; Kan, Q.; Sun, T. Corticosteroids for Treating Sepsis in Adult Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 709155.

- Aikawa, N.; Shimazaki, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Saito, H.; Maruyama, I.; Ohno, R.; Hirayama, A.; Aoki, Y.; Aoki, N. Thrombomodulin Alfa in the Treatment of Infectious Patients Complicated by Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: Subanalysis from the Phase 3 Trial. J. Shock. 2011, 35, 349–354.

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Hao, D.; Jaladat, Y.; Lu, F.; Sun, T.; Lv, C. Low-dose Heparin as Treatment for Early Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation during Sepsis: A Prospective Clinical Study. J. Exp. Ther. Med. 2014, 7, 604–608.

- Wada, H.; Matsumoto, T.; Yamashita, Y. Diagnosis and Treatment of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) According to Four DIC Guidelines. J. Intensive Care 2014, 2, 15.

- Vincent, J.-L.; Francois, B.; Zabolotskikh, I.; Daga, M.K.; Lascarrou, J.-B.; Kirov, M.Y.; Pettilä, V.; Wittebole, X.; Meziani, F.; Mercier, E. Effect of a Recombinant Human Soluble Thrombomodulin on Mortality in Patients with Sepsis-Associated Coagulopathy: The SCARLET Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Jama 2019, 321, 1993–2002.

- Yamakawa, K.; Murao, S.; Aihara, M. Recombinant Human Soluble Thrombomodulin in Sepsis-Induced Coagulopathy: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Thromb. 2019, 119, 56–65.

- Tagami, T.; Matsui, H.; Horiguchi, H.; Fushimi, K.; Yasunaga, H. Antithrombin and Mortality in Severe Pneumonia Patients with Sepsis-associated Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: An Observational Nationwide Study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 12, 1470–1479.

- Wiedermann, C.J. Antithrombin Concentrate Use in Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation of Sepsis: Meta-analyses Revisited. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 16, 455–457.

- Iba, T.; Gando, S.; Thachil, J. Anticoagulant Therapy for Sepsis-associated Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: The View from Japan. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 12, 1010–1019.

- Dhainaut, J.; Yan, S.B.; Joyce, D.E.; Pettilä, V.; Basson, B.; Brandt, J.T.; Sundin, D.P.; Levi, M. Treatment Effects of Drotrecogin Alfa (Activated) in Patients with Severe Sepsis with or without Overt Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation 1. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2004, 2, 1924–1933.

- Aoki, N.; Matsuda, T.; Saito, H.; Takatsuki, K.; Okajima, K.; Takahashi, H.; Takamatsu, J.; Asakura, H.; Ogawa, N. A Comparative Double-Blind Randomized Trial of Activated Protein C and Unfractionated Heparin in the Treatment of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. J. Int. J. Hematol. 2002, 75, 540–547.

- Warren, B.L.; Eid, A.; Singer, P.; Pillay, S.S.; Carl, P.; Novak, I.; Chalupa, P.; Atherstone, A.; Pénzes, I.; Kübler, A. High-Dose Antithrombin III in Severe Sepsis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2001, 286, 1869–1878.

- Nishida, O.; Ogura, H.; Egi, M.; Fujishima, S.; Hayashi, Y.; Iba, T.; Imaizumi, H.; Inoue, S.; Kakihana, Y.; Kotani, J. The Japanese Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2016 (J-SSCG 2016). J. Intensive Care 2018, 6, 7.

- Yao, Y.Y.; Lin, L.L.; Gu, H.Y.; Wu, J.Y.; Niu, Y.M.; Zhang, C. Are Corticosteroids Beneficial for Sepsis and Septic Shock? Based on Pooling Analysis of 16 Studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 714.

- Valeriani, E.; Squizzato, A.; Gallo, A.; Porreca, E.; Vincent, J.; Iba, T.; Hagiwara, A.; Di Nisio, M. Efficacy and Safety of Recombinant Human Soluble Thrombomodulin in Patients with Sepsis-associated Coagulopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 1618–1625.

- Iba, T.; Levy, J.H. Sepsis-Induced Coagulopathy and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. J. Anesthesiol. 2020, 132, 1238–1245.

- Lamontagne, F.; Masse, M.-H.; Menard, J.; Sprague, S.; Pinto, R.; Heyland, D.K.; Cook, D.J.; Battista, M.-C.; Day, A.G.; Guyatt, G.H. Intravenous Vitamin C in Adults with Sepsis in the Intensive Care Unit. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2387–2398.

- Amrein, K.; Oudemans-van Straaten, H.M.; Berger, M.M. Vitamin Therapy in Critically Ill Patients: Focus on Thiamine, Vitamin C, and Vitamin D. J. Intensive Care Med. 2018, 44, 1940–1944.

- Carr, A.C.; Maggini, S. Vitamin C and Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1211.

- Muhammad, M.; Jahangir, A.; Kassem, A.; Sattar, S.B.A.; Jahangir, A.; Sahra, S.; Niazi, M.R.K.; Mustafa, A.; Zia, Z.; Siddiqui, F.S. The Role and Efficacy of Vitamin C in Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Adv. Respir. Med. 2022, 90, 281–299.

- Truwit, J.D.; Hite, R.D.; Morris, P.E.; DeWilde, C.; Priday, A.; Fisher, B.; Thacker, L.R.; Natarajan, R.; Brophy, D.F.; Sculthorpe, R. Effect of Vitamin C Infusion on Organ Failure and Biomarkers of Inflammation and Vascular Injury in Patients with Sepsis and Severe Acute Respiratory Failure: The CITRIS-ALI Randomized Clinical Trial. J. JAMA 2019, 322, 1261–1270.

- Brown, J.; Robertson, C.; Sevilla, L.; Garza, J.; Rashid, H.; Benitez, A.C.; Shipotko, M.; Ali, Z. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Possible Role of Vitamin c in Sepsis. J. Cureus 2022, 14, e32886.

- Ammar, M.A.; Ammar, A.A.; Condeni, M.S.; Bell, C.M. Vitamin C for Sepsis and Septic Shock. J. Am. J. Ther. 2021, 28, e649–e679.

- Kashiouris, M.G.; L’Heureux, M.; Cable, C.A.; Fisher, B.J.; Leichtle, S.W.; Fowler, A.A. The Emerging Role of Vitamin C as a Treatment for Sepsis. J. Nutr. 2020, 12, 292.

- Adelborg, K.; Larsen, J.B.; Hvas, A. Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: Epidemiology, Biomarkers, and Management. J. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 192, 803–818.

- Carey, M.J.; Rodgers, G.M. Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: Clinical and Laboratory Aspects. J. Am. J. Hematol. 1998, 59, 65–73.

- Papageorgiou, C.; Jourdi, G.; Adjambri, E.; Walborn, A.; Patel, P.; Fareed, J.; Elalamy, I.; Hoppensteadt, D.; Gerotziafas, G.T. Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: An Update on Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Strategies. J. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2018, 24, 8S–28S.

- Wada, H.; Asakura, H.; Okamoto, K.; Iba, T.; Uchiyama, T.; Kawasugi, K.; Koga, S.; Mayumi, T.; Koike, K.; Gando, S. Expert Consensus for the Treatment of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation in Japan. J. Thromb. Res. 2010, 125, 6–11.

- Schouten, M.; van der Sluijs, K.F.; Gerlitz, B.; Grinnell, B.W.; Roelofs, J.J.T.H.; Levi, M.M.; van ’t Veer, C.; Poll, T.V.D. Activated Protein C Ameliorates Coagulopathy but Does Not Influence Outcome in Lethal H1N1 Influenza: A Controlled Laboratory Study. Crit. Care 2010, 14, R65.

- Zeerleder, S.; Hack, C.E.; Wuillemin, W.A. Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation in Sepsis. J. Chest 2005, 128, 2864–2875.

- Andrew, M.; Vegh, P.; Caco, C.; Kirpalani, H.; Jefferies, A.; Ohlsson, A.; Watts, J.; Saigal, S.; Milner, R.; Wang, E. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Platelet Transfusions in Thrombocytopenic Premature Infants. J. Pediatr. 1993, 123, 285–291.

- Estcourt, L.J.; Desborough, M.J.R.; Hopewell, S.; Doree, C.; Stanworth, S.J. Comparison of Different Platelet Transfusion Thresholds Prior to Insertion of Central Lines in Patients with Thrombocytopenia. J. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD011771.

- He, S.; Fan, C.; Ma, J.; Tang, C.; Chen, Y. Platelet Transfusion in Patients with Sepsis and Thrombocytopenia: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis Using a Large ICU Database. J. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 830177.

- Rhodes, A.; Evans, L.E.; Alhazzani, W.; Levy, M.M.; Antonelli, M.; Ferrer, R.; Kumar, A.; Sevransky, J.E.; Sprung, C.L.; Nunnally, M.E.; et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 486–552.

- Yatabe, T.; Inoue, S.; Sakamoto, S.; Sumi, Y.; Nishida, O.; Hayashida, K.; Hara, Y.; Fukuda, T.; Matsushima, A.; Matsuda, A. The Anticoagulant Treatment for Sepsis Induced Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation; Network Meta-Analysis. J. Thromb. Res. 2018, 171, 136–142.

- Muzaffar, S.N.; Baronia, A.K.; Azim, A.; Verma, A.; Gurjar, M.; Poddar, B.; Singh, R.K. Thromboelastography for Evaluation of Coagulopathy in Nonbleeding Patients with Sepsis at Intensive Care Unit Admission. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. Off. Publ. Indian Soc. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 21, 268.

- Christaki, E.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J. The Beginning of Personalized Medicine in Sepsis: Small Steps to a Bright Future. J. Clin. Genet. 2014, 86, 56–61.

- Kudo, D.; Hayakawa, M.; Ono, K.; Yamakawa, K. Impact of Non-Anticoagulant Therapy on Patients with Sepsis-Induced Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: A Multicenter, Case-Control Study. J. Thromb. Res. 2018, 163, 22–29.

- Mohammad, R.A. Use of Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor in Patients with Severe Sepsis or Septic Shock. J. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2010, 67, 1238–1245.

- Mathias, B.; Szpila, B.E.; Moore, F.A.; Efron, P.A.; Moldawer, L.L. A Review of GM-CSF Therapy in Sepsis. J. Med. 2015, 94, e2044.

- Le Blanc, K.; Frassoni, F.; Ball, L.; Locatelli, F.; Roelofs, H.; Lewis, I.; Lanino, E.; Sundberg, B.; Bernardo, M.E.; Remberger, M. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Treatment of Steroid-Resistant, Severe, Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease: A Phase II Study. J. Lancet 2008, 371, 1579–1586.

- Weiss, A.R.R.; Dahlke, M.H. Immunomodulation by Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs): Mechanisms of Action of Living, Apoptotic, and Dead MSCs. J. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1191.

- Elahi, K.C.; Klein, G.; Avci-Adali, M.; Sievert, K.D.; MacNeil, S.; Aicher, W.K. Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells from Different Sources Diverge in Their Expression of Cell Surface Proteins and Display Distinct Differentiation Patterns. J. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 5646384.

- Hass, R.; Kasper, C.; Böhm, S.; Jacobs, R. Different Populations and Sources of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC): A Comparison of Adult and Neonatal Tissue-Derived MSC. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2011, 9, 12.

- De Witte, S.F.H.; Lambert, E.E.; Merino, A.; Strini, T.; Douben, H.J.C.W.; O’Flynn, L.; Elliman, S.J.; De Klein, A.J.; Newsome, P.N.; Baan, C.C. Aging of Bone Marrow–and Umbilical Cord–Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells during Expansion. J. Cytotherapy 2017, 19, 798–807.

- De Witte, S.F.H.; Merino, A.M.; Franquesa, M.; Strini, T.; Van Zoggel, J.A.A.; Korevaar, S.S.; Luk, F.; Gargesha, M.; O’Flynn, L.; Roy, D. Cytokine Treatment Optimises the Immunotherapeutic Effects of Umbilical Cord-Derived MSC for Treatment of Inflammatory Liver Disease. J. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 140.

- Eggenhofer, E.; Popp, F.C.; Mendicino, M.; Silber, P.; Van’T Hof, W.; Renner, P.; Hoogduijn, M.J.; Pinxteren, J.; van Rooijen, N.; Geissler, E.K. Heart Grafts Tolerized through Third-Party Multipotent Adult Progenitor Cells Can Be Retransplanted to Secondary Hosts with No Immunosuppression. J. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2013, 2, 595–606.

- Ge, W.; Jiang, J.; Arp, J.; Liu, W.; Garcia, B.; Wang, H.J.T. Regulatory T-Cell Generation and Kidney Allograft Tolerance Induced by Mesenchymal Stem Cells Associated with Indoleamine 2, 3-Dioxygenase Expression. J. Stem Cells Int. 2010, 90, 1312–1320.

- Riquelme, P.; Haarer, J.; Kammler, A.; Walter, L.; Tomiuk, S.; Ahrens, N.; Wege, A.K.; Goecze, I.; Zecher, D.; Banas, B. TIGIT+ ITregs Elicited by Human Regulatory Macrophages Control T Cell Immunity. J. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2858.

- Takahashi, G.; Shibata, S.; Ishikura, H.; Miura, M.; Fukui, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Endo, S. Presepsin in the Prognosis of Infectious Diseases and Diagnosis of Infectious Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: A Prospective, Multicentre, Observational Study. J. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. EJA 2015, 32, 199–206.

- Chang, P.; Liao, Y.; Guan, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, M.; Hu, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, H.; Cen, Z.; Tang, Y. Combined Treatment with Hydrocortisone, Vitamin C, and Thiamine for Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Chest 2020, 158, 174–182.

- Fujii, T.; Luethi, N.; Young, P.J.; Frei, D.R.; Eastwood, G.M.; French, C.J.; Deane, A.M.; Shehabi, Y.; Hajjar, L.A.; Oliveira, G.; et al. Effect of Vitamin C, Hydrocortisone, and Thiamine vs Hydrocortisone Alone on Time Alive and Free of Vasopressor Support Among Patients with Septic Shock: The VITAMINS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 323, 423–431.

- Hwang, Y.S.; Suzuki, S.; Seita, Y.; Ito, J.; Sakata, Y.; Aso, H.; Sato, K.; Hermann, B.P.; Sasaki, K. Reconstitution of Prospermatogonial Specification in Vitro from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5656.

- Iglesias, J.; Vassallo, A.V.; Patel, V.V.; Sullivan, J.B.; Cavanaugh, J.; Elbaga, Y. Outcomes of Metabolic Resuscitation Using Ascorbic Acid, Thiamine, and Glucocorticoids in the Early Treatment of Sepsis: The ORANGES Trial. J. Chest 2020, 158, 164–173.

- Moskowitz, A.; Huang, D.T.; Hou, P.C.; Gong, J.; Doshi, P.B.; Grossestreuer, A.V.; Andersen, L.W.; Ngo, L.; Sherwin, R.L.; Berg, K.M.; et al. Effect of Ascorbic Acid, Corticosteroids, and Thiamine on Organ Injury in Septic Shock: The ACTS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 324, 642–650.

- Sevransky, J.E.; Rothman, R.E.; Hager, D.N.; Bernard, G.R.; Brown, S.M.; Buchman, T.G.; Busse, L.W.; Coopersmith, C.M.; DeWilde, C.; Ely, E.W.; et al. Effect of Vitamin C, Thiamine, and Hydrocortisone on Ventilator- and Vasopressor-Free Days in Patients with Sepsis: The VICTAS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 742–750.

- Müller, M.C.; Meijers, J.C.M.; Vroom, M.B.; Juffermans, N.P. Utility of Thromboelastography and/or Thromboelastometry in Adults with Sepsis: A Systematic Review. J. Crit. Care 2014, 18, R30.

- Bolliger, D.; Seeberger, M.D.; Tanaka, K.A. Principles and Practice of Thromboelastography in Clinical Coagulation Management and Transfusion Practice. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2012, 26, 1–13.

- Iba, T.; Levy, J.H.; Raj, A.; Warkentin, T.E. Advance in the Management of Sepsis-Induced Coagulopathy and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 728.

- Jarczak, D.; Kluge, S.; Nierhaus, A. Sepsis—Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Concepts. J. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 609.

- Peters van Ton, A.M.; Kox, M.; Abdo, W.F.; Pickkers, P. Precision Immunotherapy for Sepsis. J. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1926.

- Mithal, L.B.; Arshad, M.; Swigart, L.R.; Khanolkar, A.; Ahmed, A.; Coates, B.M. Mechanisms and Modulation of Sepsis-Induced Immune Dysfunction in Children. J. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 91, 447–453.

- Giarratano, A. Sepsis-Induced Coagulopathy and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. J. AboutOpen 2022, 9, 58–60.

- Inata, Y. Should We Treat Sepsis-Induced DIC with Anticoagulants? J. Intensive Care 2020, 8, 18.

- Kudo, D.; Hayakawa, M.; Iijima, H.; Yamakawa, K.; Saito, S.; Uchino, S.; Iizuka, Y.; Sanui, M.; Takimoto, K.; Mayumi, T. The Treatment Intensity of Anticoagulant Therapy for Patients with Sepsis-Induced Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation and Outcomes: A Multicenter Cohort Study. J. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2019, 25, 1076029619839154.

- Okamoto, K.; Tamura, T.; Sawatsubashi, Y. Sepsis and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. J. Intensive Care 2016, 4, 23.

- Nasef, A.; Mathieu, N.; Chapel, A.; Frick, J.; François, S.; Mazurier, C.; Boutarfa, A.; Bouchet, S.; Gorin, N.-C.; Thierry, D. Immunosuppressive Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Involvement of HLA-G. J. Transplant. 2007, 84, 231–237.

- Moll, G.; Geißler, S.; Catar, R.; Ignatowicz, L.; Hoogduijn, M.J.; Strunk, D.; Bieback, K.; Ringdén, O. Cryopreserved or Fresh Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: Only a Matter of Taste or Key to Unleash the Full Clinical Potential of MSC Therapy? J. Biobanking Cryopreserv. Stem Cells 2016, 951, 77–98.

- Luk, F.; Carreras-Planella, L.; Korevaar, S.S.; de Witte, S.F.H.; Borràs, F.E.; Betjes, M.G.H.; Baan, C.C.; Hoogduijn, M.J.; Franquesa, M. Inflammatory Conditions Dictate the Effect of Mesenchymal Stem or Stromal Cells on B Cell Function. J. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1042.

- Németh, K.; Leelahavanichkul, A.; Yuen, P.S.T.; Mayer, B.; Parmelee, A.; Doi, K.; Robey, P.G.; Leelahavanichkul, K.; Koller, B.H.; Brown, J.M. Bone Marrow Stromal Cells Attenuate Sepsis via Prostaglandin E2–Dependent Reprogramming of Host Macrophages to Increase Their Interleukin-10 Production. J. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 42–49.

- Obermajer, N.; Popp, F.C.; Soeder, Y.; Haarer, J.; Geissler, E.K.; Schlitt, H.J.; Dahlke, M.H. Conversion of Th17 into IL-17Aneg Regulatory T Cells: A Novel Mechanism in Prolonged Allograft Survival Promoted by Mesenchymal Stem Cell–Supported Minimized Immunosuppressive Therapy. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 4988–4999.

- Popp, F.C.; Eggenhofer, E.; Renner, P.; Slowik, P.; Lang, S.A.; Kaspar, H.; Geissler, E.K.; Piso, P.; Schlitt, H.J.; Dahlke, M.H. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Can Induce Long-Term Acceptance of Solid Organ Allografts in Synergy with Low-Dose Mycophenolate. J. Transplant. Immunol. 2008, 20, 55–60.

- Spaggiari, G.M.; Capobianco, A.; Abdelrazik, H.; Becchetti, F.; Mingari, M.C.; Moretta, L. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Inhibit Natural Killer–Cell Proliferation, Cytotoxicity, and Cytokine Production: Role of Indoleamine 2, 3-Dioxygenase and Prostaglandin E2. J. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2008, 111, 1327–1333.

- Wu, Y.; Hoogduijn, M.J.; Baan, C.C.; Korevaar, S.S.; de Kuiper, R.; Yan, L.; Wang, L.; van Besouw, N.M. Adipose Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Have a Heterogenic Cytokine Secretion Profile. J. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 4960831.

- Chang, C.-L.; Leu, S.; Sung, H.-C.; Zhen, Y.-Y.; Cho, C.-L.; Chen, A.; Tsai, T.-H.; Chung, S.-Y.; Chai, H.-T.; Sun, C.-K. Impact of Apoptotic Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Attenuating Organ Damage and Reducing Mortality in Rat Sepsis Syndrome Induced by Cecal Puncture and Ligation. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 1–14.

- Baxter, M.A.; Wynn, R.F.; Jowitt, S.N.; Wraith, J.E.; Fairbairn, L.J.; Bellantuono, I. Study of Telomere Length Reveals Rapid Aging of Human Marrow Stromal Cells Following In Vitro Expansion. J. Stem Cells 2004, 22, 675–682.

- Bartholomew, A.; Sturgeon, C.; Siatskas, M.; Ferrer, K.; McIntosh, K.; Patil, S.; Hardy, W.; Devine, S.; Ucker, D.; Deans, R. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Suppress Lymphocyte Proliferation in Vitro and Prolong Skin Graft Survival in Vivo. J. Exp. Hematol. 2002, 30, 42–48.

- Bonab, M.M.; Alimoghaddam, K.; Talebian, F.; Ghaffari, S.H.; Ghavamzadeh, A.; Nikbin, B. Aging of Mesenchymal Stem Cell in Vitro. J. BMC Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 14.

- Nadarajan, S.; Lambert, T.J.; Altendorfer, E.; Gao, J.; Blower, M.D.; Waters, J.C.; Colaiá Covo, M.P. Polo-like Kinase-Dependent Phosphorylation of the Synaptonemal Complex Protein SYP-4 Regulates Double-Strand Break Formation through a Negative Feedback Loop. Elife 2017, 6, e23437.

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, L.; Zhang, T.; Cheng, J.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y. Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Instruct Monocytes towards an IL10-Producing Phenotype by Secreting IL6 and HGF. J. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37566.

- Forbes, G.M.; Sturm, M.J.; Leong, R.W.; Sparrow, M.P.; Segarajasingam, D.; Cummins, A.G.; Phillips, M.; Herrmann, R.P. A Phase 2 Study of Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Luminal Crohn’s Disease Refractory to Biologic Therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 64–71.

- González, M.A.; Gonzalez–Rey, E.; Rico, L.; Büscher, D.; Delgado, M. Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Alleviate Experimental Colitis by Inhibiting Inflammatory and Autoimmune Responses. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 136, 978–989.

- Hu, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Gao, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, W.; Jia, Z.; Yan, S. Long Term Effects of the Implantation of Wharton’s Jelly-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells from the Umbilical Cord for Newly-Onset Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Endocr. J. 2013, 60, 347–357.

- Iba, T.; Umemura, Y.; Wada, H.; Levy, J.H. Roles of Coagulation Abnormalities and Microthrombosis in Sepsis: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. J. Arch. Med. Res. 2021, 52, 788–797.

- Reinders, M.E.J.; de Fijter, J.W.; Roelofs, H.; Bajema, I.M.; de Vries, D.K.; Schaapherder, A.F.; Claas, F.H.J.; van Miert, P.P.M.C.; Roelen, D.L.; van Kooten, C. Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for the Treatment of Allograft Rejection after Renal Transplantation: Results of a Phase I Study. J. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2013, 2, 107–111.

- Schellenberg, A.; Lin, Q.; Schüler, H.; Koch, C.M.; Joussen, S.; Denecke, B.; Walenda, G.; Pallua, N.; Suschek, C.V.; Zenke, M. Replicative Senescence of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Causes DNA-Methylation Changes Which Correlate with Repressive Histone Marks. J. Aging 2011, 3, 873.

- Yin, J.Q.; Zhu, J.; Ankrum, J.A. Manufacturing of Primed Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Therapy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 3, 90–104.

- Da Meirelles, L.S.; Chagastelles, P.C.; Nardi, N.B. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Reside in Virtually All Post-Natal Organs and Tissues. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 2204–2213.

- Lin, H.-Y. The Severe COVID-19: A Sepsis Induced by Viral Infection? And Its Immunomodulatory Therapy. J. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2020, 23, 190–195.

- Unar, A.; Imtiaz, M.; Trung, T.T.; Rafiq, M.; Fatmi, M.Q.; Jafar, T.H. Structural and Functional Analyses of SARS-CoV-2 RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Protein and Complementary vs. Synthetic Drugs against COVID-19 and the Exploration of Binding Sites for Docking, Molecular Dynamics Simulation, and Density Functional Theory Studies. Curr. Bioinform. 2022, 17, 632–656.

More

Information

Subjects:

Infectious Diseases

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

25 Sep 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No