Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lucas Fornari Laurindo | -- | 5949 | 2023-06-14 16:11:27 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 5949 | 2023-06-15 04:33:28 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Direito, R.; Barbalho, S.M.; Figueira, M.E.; Minniti, G.; De Carvalho, G.M.; De Oliveira Zanuso, B.; De Oliveira Dos Santos, A.R.; De Góes Corrêa, N.; Rodrigues, V.D.; De Alvares Goulart, R.; et al. Medicinal Plants Targrting NLRP3 Inflammasome in IBD. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45592 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Direito R, Barbalho SM, Figueira ME, Minniti G, De Carvalho GM, De Oliveira Zanuso B, et al. Medicinal Plants Targrting NLRP3 Inflammasome in IBD. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45592. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Direito, Rosa, Sandra Maria Barbalho, Maria Eduardo Figueira, Giulia Minniti, Gabriel Magno De Carvalho, Bárbara De Oliveira Zanuso, Ana Rita De Oliveira Dos Santos, Natália De Góes Corrêa, Victória Dogani Rodrigues, Ricardo De Alvares Goulart, et al. "Medicinal Plants Targrting NLRP3 Inflammasome in IBD" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45592 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Direito, R., Barbalho, S.M., Figueira, M.E., Minniti, G., De Carvalho, G.M., De Oliveira Zanuso, B., De Oliveira Dos Santos, A.R., De Góes Corrêa, N., Rodrigues, V.D., De Alvares Goulart, R., Guiguer, E.L., Araújo, A.C., Bosso, H., & Fornari Laurindo, L. (2023, June 14). Medicinal Plants Targrting NLRP3 Inflammasome in IBD. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45592

Direito, Rosa, et al. "Medicinal Plants Targrting NLRP3 Inflammasome in IBD." Encyclopedia. Web. 14 June, 2023.

Copy Citation

The Nod-like Receptor (NLR) Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, a key regulator found in immunological and epithelial cells, is crucial in inducing inflammatory diseases, promoting immune responses to the gut microbiota, and regulating the integrity of the intestinal epithelium. Its downstream effectors include caspase-1 and interleukin (IL)-1β.

NLRP3

NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3

inflammasome

inflammatory bowel disease

ulcerative colitis

cancer

medicinal plants

phytochemicals

Crohn’s disease

inflammation

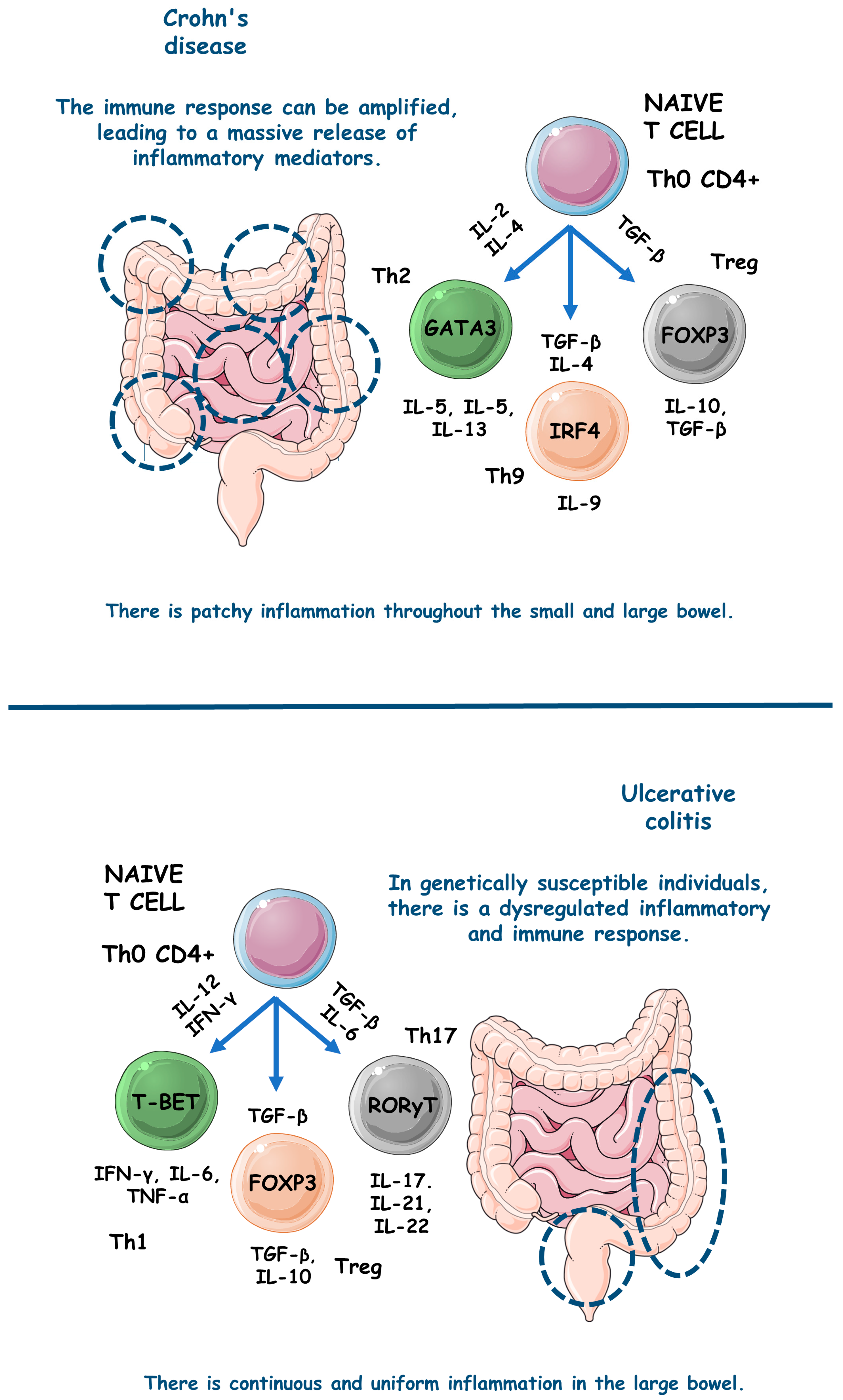

1. Physiopathology of Ulcerative Colitis

UC is a chronic immune-mediated colon disease that is primarily an inflammatory disorder. In genetically susceptible individuals, it is hypothesized that exposure to environmental risk factors triggers an inappropriate immune response to the enteric commensal bacteria that compose the gut microbiota. Although only 8% to 14% of total patients affected by UC have a family history of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBDs), first-degree relatives of individuals diagnosed with UC have four times the risk of developing the disease when in comparison with other patients. Additionally, monozygotic twins have concordance rates of 6% to 13% of developing UC [1][2]. Worldwide, UC prevalence is rising annually, ranging from 8.8 to 23.1 per 100,000 individuals in North American countries. UC is a disease that may occur during any age, but the peak of incidence in the 2nd to the 4th decade of life appears at the same incidences between men and women patients. The prevalence of UC has risen due to including phenotypes with lower mortality rates, younger ages of onset, and an absence of a potent cure. As complications, UC usually is accompanied by a recurrence of gastrointestinal infections, malignancies, and thromboembolic events [3][4][5][6].

Several different environmental factors serve as triggers for the development of UC. Before diagnosis, the onset usually has multiple gastrointestinal infections and exposure to non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. These events might lead to profound changes in the bowel flora and trigger a chronic inflammatory process that, in genetically predisposed patients, could influence the occurrence of UC. On the other hand, appendicectomy has been used to treat UC and reduce the risk of the disease’s development [6][7][8][9].

Pathological changes in the intestinal epithelial barrier, gut microbiota, and immune system characterize UC. The disruption of enterocytes tight junctions and intestinal mucus layer covering the gut epithelial wall leads to increased permeability of the intestinal epithelium, allowing commensal bacteria to invade other layers of the bowel tissue. Innate immune cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages recognize the bacterial antigen of the commensals through Toll-like receptors (TLRs), switching from a tolerogenic to an active phenotype. These events stimulate the activation of the transcription of multiple pro-inflammatory genes and the production and secretion of various pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-12, IL-23, IL-1β, and IL-6 [7][10][11].

Once commensal bacterial antigens are processed, stimulated intestinal dendritic cells and macrophages present the antigens to naïve cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) T cells. Consequently, these naïve cells differentiate into T helper (Th) 2 effector cells and produce the specific interleukin IL-4, which plays a role in the immune response against commensal bacteria. However, many other immune cells are involved in the pathogenesis of UC. Natural killer (NK) cells are the primary source of IL-13, linked to intestinal epithelial cell barrier disruption during the disease process. As the intestine becomes inflamed, it expresses more adhesive molecules to leukocytes, leading to the increased entry of T cells into the lamina propria of the bowel wall. Meanwhile, pro-inflammatory chemokines such as C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand (CXCL) 1 (CXCL1), CXCL3, and CXCL8 are upregulated in the intestine, perpetuating the inflammatory cycle of colitis [7][10][11][12].

The diagnosis of UC is based principally on clinical symptomatology and objective finding from the endoscopic examination. Additionally, histological examination can also be a priority. In UC, the inflammation generally starts in the rectum of the patients and extends to proximal areas uninterruptedly, involving part of or the entire colon. Clinically, the disease presents rectal bleeding, feces urgency, diarrhea, tenesmus, fever, and abdominal pain. The main endoscopic features are erythema, friability, granularity, loss of vascular patterns, ulcerations, spontaneous bleeding, and erosions. Histologically, the disease manifests distortion of crypt architecture, crypt abscesses, shortening of the crypts, erosions, ulcerations, lymphoid aggregates, mucin depletion, and lamina propria cellular infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. Because diarrhea is a diagnostic criterion, it is fundamental to rule out infectious and non-infectious causes of diarrhea before a complete diagnosis. Depending on the involved affected segments of the colon, UC can be defined as proctitis, pancolitis, or left-sided colitis [6][7][11][13].

The treatment of UC involves mesalamine, immunosuppressive drugs, corticosteroids, and monoclonal antibodies against TNF-α [5][7][14]. The aims of a successful treatment consist of maintaining a steroid-free remission, mucosal healing, preventing surgery necessity as well as hospital admission, avoiding disability, and improving the quality of life for all patients [3][11][12]. Additionally, treatment must be tailored according to the disease extent (proctitis, pancolitis, or left-sided) and disease activity (mild, moderate, or severe). UC and CD patients often consider whether to withdraw treatment with their doctors, especially in cases of steroid-free remission. Previous research showed that up to 20 to 50% of patients at one year and 50 to 80% of patients beyond five years have a risk of relapse after stopping therapy, which is considered high. This data suggests that stopping treatment may not be a default strategy in fighting IBD. However, some patients may not experience relapse over a mid-term period, and others may benefit from a drug-free period before starting a new treatment cycle. Given the above, identifying the patients who can successfully withdraw from treatment must follow strict criteria. These may include the risk of relapse (related to factors such as mucosal healing and biomarkers), the consequences of a potential deterioration, the side effects and tolerance of the ongoing therapy, the patients’ priorities and preferences, and their disease’s costs. Ongoing research aims to provide a decisional algorithm that integrates these parameters and proposes to help patients and doctors make an appropriate decision for each of their cases [15][16][17].

2. Physiopathology of Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s Disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory intestinal condition initially considered regional ileitis but is now recognized as affecting the entire intestine. During CD, the distal ileum is the most frequently affected area. Even with the improvements in alimentation, CD incidence is increasing worldwide, and patients experience periods of flares and remissions during the disease. Various risk factors influence CD pathophysiology, including environmental, immunological, genetic, and microbiota-related factors. Inflammation caused by inflammatory cells is a crucial driver of CD pathogenesis, making it a significant treatment target. Treatment aims to halt the inflammatory cascade by reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the bowel [18][19][20][21].

As commented above, CD pathogenesis is based on the inflammation of the intestinal tissues, which is caused by an unrestrainable immunological response against the bacteria that compose the luminal microbiota of the human bowel. These bacteria present antigens that are recognized by antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Immune cells such as CD4 T lymphocytes, CD8 T lymphocytes, B-cells, NK cells, and CD14 monocytes start infiltrating the affected patients’ gut. Given the nature of the CD, it is known that immunological susceptibility in some innate immune response mechanisms in the defense against infections plays a critical role in the tolerance break of the immune system against intestinal bacteria. Reduced mucous production also helps this tolerance break insofar as it has been shown that variants of the Muc2 mucous-reduction genes are correlated with CD in many mouse models of the disease. People with altered interactions with the intestinal lumen commensal bacteria also have an increased risk of developing CD, such as in the case of the Galactoside alpha-(1,2)-fucosyltransferase 2 (FUT2) genetic variances, in which the patients encode a fucosyltransferase enzyme incapable of secreting antigens such as ABO [18][22][23].

The defects in the intestinal mucous barrier associated with CD involve primarily innate immunity. However, adaptive immunity relies on a Th1 lymphocytic immunological response mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-12, IL-23, and IL-34. Treg cells also contribute to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines during CD development. The migration of Th1 lymphocytes and Treg cells to the affected sites is facilitated by interactions with integrins (such as the receptor for α4β4 integrin) and adhesion molecules (such as leucocyte MAcCAM-1), which are mediated by various chemokines and metalloproteinases. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1 and MMP-3), produced through the stimulation of leukocyte proteins such as CD44 and CD26, are among the factors that contribute to the inflammatory response [18][20][24].

Although other T cell subsets than Th1 can emerge during CD. Th17 cells are relevant examples, whereas the most prominent involved pro-inflammatory cytokines are the TNF-α, IL-12, and IL-23. As aforementioned, the Th2 response is antagonistic to CD, because Th2 cells are characteristic of UC. Apart from those most common pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-34 also plays a critical role during CD development and has been associated with areas of very active inflammation due to its power to induce the release of TNF-α and IL-6 through extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK)-mediated mechanisms and Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL) 20 (CCL20) through the interaction with its Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 (M-CSFR1) receptor. CD inflammation is typically transmural and, on the pathologists’ examinations, granulomas with a discontinuous distribution along the longitudinal axis are frequently found, leading to irreversible tissue damage due to intestinal stenosis and fistulas, inflammatory masses, or even intra-abdominal abscesses derived from possible concomitant infections [18][25][26].

The immune network that emerges in CD derives from the microbial-associated molecular pattern (MAMP) recognition by the leukocytes involved in the defense of the intestinal mucosa. Toll-like receptors sense these molecular bacterial patterns on immune cells, contributing to the disease’s chronic inflammation [18][26].

figure 1 comparatively exemplifies the pathophysiological steps involved in the occurrence of UC and CD.

figure 1. The main pathophysiological steps involved in the occurrence of UC and CD. ↑, increase; FOXP3, forkhead box P3; GATA3, GATA (Erythroid transcription factor) Binding Protein 3; IFN-γ, interferon gama; IL, interleukin; IRF4, Interferon regulatory factor 4; T-BET, T-box transcription factor TBX21; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; Th, T helper; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alfa; Treg, T regulatory cell.

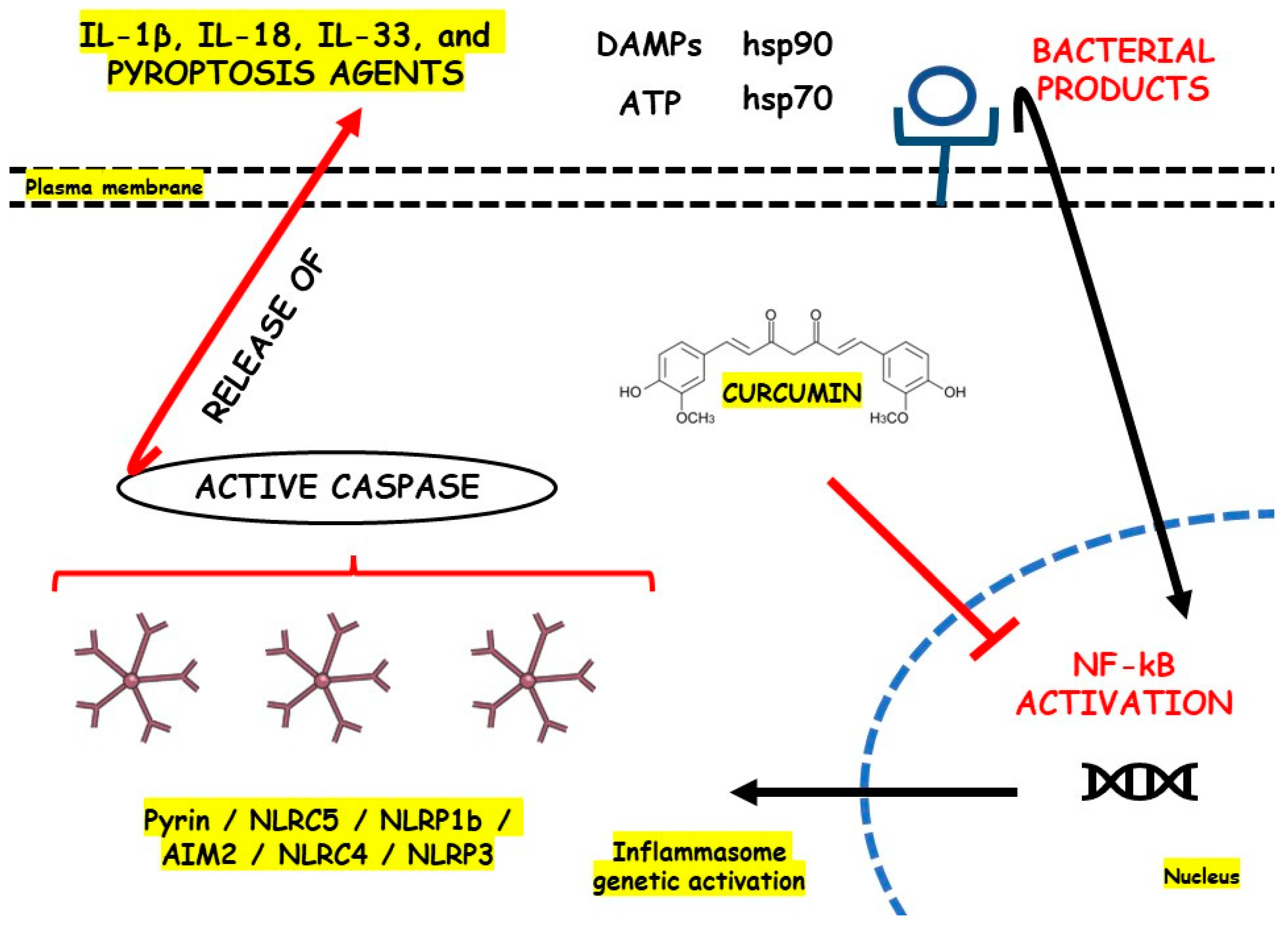

3. NLRP3 Inflammasome: Implications for IBD

Inflammasomes are cytoplasmic multimeric complexes of proteins that not only mediate IL-1β and IL-18 activation but also induce pyroptosis. Primarily, inflammasomes are mainly responsible for initiating and sustaining the innate immunological response against many kinds of stressors (endogenous and exogenous). NLRP3 is unique among all NLR families of inflammasome receptors and is the only known member that seems to be indirectly activated through pathogenic and sterile pro-inflammatory signals. In the pathogenic field, bacterial and viral pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) such as nucleic acids and LPS and other bacterial toxins such as nigericin and gramicidin activate the NLRP3 domain. In the sterile area, damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), reactive oxygen species (ROS), extracellular presence of ATP, potassium efflux, and various metabolic crystals can also activate the NLRP3 domain. NLRP3 depends on a sensor (NLRP3), an adaptor (ASC or PYARD), and an effector (caspase-1). Theoretically, priming and activation steps are necessary to activate NLRP3. In the priming step, three components (NLRP3, pro-IL-1-β, and caspase-1) must be upregulated, and PAMPs and DAMPs trigger this upregulation by stimulating pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and cytokine receptors, including TLRs and IL-1R, respectively. Furthermore, many stimuli activate the proper NLRP3 regulator during the activation step. The incentives can be endogenous, such as DAMPs, or exogenous, such as PAMPs, K+, Cl− ions efflux, or the flux of Ca2+ [27][28][29].

NLRs comprise an N-terminal domain called an effector, a C-terminal leucine-rich repeats (LRR), and a central nucleotide-binding domain (NBD/NOD/NACHT). The subdomains NACHT and LRR are the only ones conserved in all NLRs except NLRP10, and the N-terminal effector domain can vary. Due to N-terminal variance, NLRs can interact with various partners and recruit many integrators. The activation of NLRP3 inflammasome is evidenced during the pathogenesis of many different inflammatory and immunomodulated diseases such as diabetes, IBD, and atherosclerosis. However, to cause illness, NLRP3 must be overactivated. The most studied inflammatory pathway NLRs activate is NF-kB, but they also conduct mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, antigen presentation, assembly of cytosolic signals transduction complexes, and embryonic development [30][31]. Thus, NLRP3 should be tightly regulated to prevent unwanted disease processes and body damage through excessive inflammation.

After sensing dangerous signals, which presumably occurred by the LRR domain of the NLRP3 complex, NLRP3 monomers start to induce oligomerization and interact with pyrin domains called PYD of ASC via homophilic interactions. Then, ASC, as an adaptor, becomes a recruiter of cysteine protease pro-caspase-1 through a caspase recruitment domain (CARD). As a result, the autocatalysis and further activation of caspase-1 lead to the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 production and pyroptosis. For the proximity-induced activation of NLRs inflammasomes such as NLRP3, recent structural studies revealed that two successive and interconnected steps in nucleation-induced and “prion-like” polymerization are necessary. These are the NLRP3 nucleation of the PYD filaments of ASC and pro-caspase-1 cluster within star-like fibers of ASC [30][32].

NLRP3 has also been observed to interact with nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2) in a CARD-dependent manner. This interaction plays a distinct role in processing the major NLRP3-associated pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β. Differently from other cytokines of the IL-1 family that can suppress inflammation, IL-1β stimulates it. Indeed, IL-1β is crucial in mediating pro-inflammatory responses in various tissues among multiple systemic inflammatory diseases and is associated highly with leukocytosis and elevated acute phase proteins [30][32].

Etiologically and as previously mentioned, IBD occurrence remains unclear. However, aberrant immunological responses against commensal intestinal bacteria are widely thought to underline IBD. A recent investigation found that IL-1β, not IL-18, is the most related to NLRP3 downstream during IBD and is also an essential effector of inflammatory cytokine in the intestine during CD and UC, which facilitates the formation of inflammasomes in the bowel. However, IL-18 became necessary due to its functions in maintaining the protective effect of NLRP3 in the intestine, insofar as IL-18 deficiency was associated with decreased gut protection against exacerbated inflammatory responses. In this scenario, NLRP3 can translate danger and microbial sensors into robust immune responses via NF-kB and MAPK cascades. Among mucosal cells, NLRP3 instigates pyroptosis via an activating cleavage of gasdermin D (GSDMD), an executioner for pyroptosis [33][34].

Emerging evidence indicates that the persistent activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is a crucial factor in the development of IBD [35][36][37]. As a result, targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome has been identified as a potential therapeutic approach for treating IBD. The presence of adenosine diphosphate, abundant in injured colonic tissue, has been found to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome by regulating P2Y1 receptor-mediated calcium signaling. This activation leads to the maturation and secretion of IL-1β, further exacerbating the progression of colitis [38][39][40].

Conversely, studies have demonstrated that the genetic ablation or pharmacological blockade of the P2Y1 receptor significantly alleviates DSS-induced colitis and endotoxic shock [38]. Moreover, it has been discovered that the Breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein 1/2 (BRCA1/BRCA2)-containing complex 3 and Josephin domain containing 2 facilitate NLRP3-R779C deubiquitination and the interaction between serine/threonine-protein kinase NEK7 and NLRP3 [41][42][43][44]. These interactions promote NLRP3 inflammasome activation, thereby increasing the risk of developing IBD.

In IBD, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells produce IL-1β. The leading producers are macrophages presented in the intestine lamina propria. Significantly, IL-1β triggers T cell proliferation during IBD and directly influences neutrophils recruitment to local inflammatory sites of the gut via combination with IL-1R and further activation of signaling cascades that culminate in NF-kB and MAPK pathways activation. Currently, NLRP3’s typical mediators start to divide holophotes with other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. Meanwhile, IL-1β also upregulates IL-2 receptor expression in T cells, which prolongs their survival and enhance their antibody production by direct B cell proliferation [33][45].

4. Medicinal Plants TARGETING NLRP3 inflammasome

4.1. Xianglian Pill

To test the effects of the Xianglian Pill, a composition of Coptis chinensis Franch, Evodia rutaecarpa, and Aucklandia lappa Decne, against NLRP3 activation in IBD, Dai et al. [46] studied a DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis. The results showed that after the treatment, the animals presented decreased levels of NLRP3, caspase-1, GSDMD-N, TLR4, myeloid differentiation protein (MyD88), NF-κB, p–NF–κB, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-18, and myeloperoxidase (MPO).

4.2. Litsea cubeba

Wong et al. [47] studied the effects of Litsea cubeba against NLRP3 activation in both an in vitro and in vivo models of IBD. After the treatment, the LPS and ATP stimulated J774A.1 cells presented decreased IL-1β, ASC, caspase-1, NLRP3, ROS, pyroptosis, IL-6, and mitochondrial ROS/damage relation. In addition, the DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model showed decreased levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-6.

4.3. Artemisia anomala

Hong et al. [48] evaluated the effects of Artemisia anomala against NLRP3 activation in IBD in vitro and in vivo models. After the treatment, the LPS-stimulated BMDMs cells presented decreased IL-1β, NLRP3, ASC, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7-c-jun n-terminal kinase (TAK1-JNK), caspase-1, p65 nuclear, IkappaB kinase-α (IκBα), NF-kB, lysosomal disruption, ROS, mitochondrial damage, and TNF-α expression levels. In addition, DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis presented decreased levels of IL-1β.

4.4. Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill

Bian et al. [49] utilized Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill against NLRP3 activation in a DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis. The results showed that after the treatment the animals presented increased superoxide dismutase (SOD) and zonula occludens protein 1 (ZO-1) expression levels. In addition, the mice showed decreased expression levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), MPO, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-18, TLR4, p-p65 and p-IκB-α, TLR4/NF-κB signaling, and NLRP3.

4.5. Wu-Mei-Wan

Yan et al. [50] used Wu-Mei-Wan, a mixture of Coptidis rhizoma, Phellodendri chinensis cortex, Zingiberis rhizoma recens, Typhonii rhizoma, Zanthoxyli, Mume fructus, and Ginseng radix rhizome, against NLRP3 activation in a DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis. The results showed that after the treatment, the animals presented decreased levels of NLRP3, Notch-1, NF-κBp65, p-NF-κBp65, NLRP3, IL-18, IL-6, IL-1β, co-expression of Notch-1, IL-18, TNF-α, macrophages infiltration, and interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5).

4.6. Kui Jie Tong

Xue et al. [51] used Kui Jie Tong, a mixture of Verbenae herb, Euphorbiae Humifusae herb, Arecae semen, Aurantii fructus immaturus and Angelicae sinensis radix, against NLRP3 activation in a DSS-induced mice model of colitis. The results demonstrated that after the treatment, the animals presented NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1, never in mitosis gene a (NIMA) related kinase 7 (NEK7), pyroptosis, IL-1β, IL-18, IL-33, and GSDMD.

4.7. Piper nigrum

In turn, Sudeep et al. [52] evaluated the effects of Piper nigrum against NLRP3 activation in a DSS-induced BALB/c mice model of colitis. The results demonstrated that the treated animals presented decreased TNF-α, IL-1β, NLRP3, oxidative stress (OS), and MDA, as well as increased claudin-1, occludin, SOD, catalase (CAT), and glutathione (GSH).

4.8. Morus macroura Miq

Salama et al. [53] conducted a study with an AA-induced mice model of colitis to evaluate the effects of Morus macroura Miq against NLRP3 activation during this model of IBD. The results showed that, after treatment, the animals presented increased levels of micro ribonucleic acid 223 (miRNA-223), SOD and GSH, as well as decreased levels of TNF-α, NFκB-p65, caspase-1, NLRP3, MDA, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-18, ROS, and nitrate/nitrite relation.

4.9. Patrinia villosa

Wang et al. [54] conducted an in vivo study with a TNBS-induced Sprague-Dawley rat model of colitis to evaluate the roles of Patrinia villosa against NLRP3 activation in this model of IBD. The results showed that the plant dry leaf extract could effectively decrease the expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, NF-κB, p-NF-κB, NLRP3, and caspase-1 among the treated animals.

4.10. Ficus pandurata Hance

Dai et al. [55] studied a DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis to evaluate the roles of Ficus pandurata Hance against NLRP3 activation in this model of IBD. The results showed that the treatment with stem, leaf, root, and whole plant extracts could effectively decrease the animals’ expression of TLR4, MyD88, NF-κB, phospho-NF-κB, MDA, kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1), NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2), and p22-phox, as well as increase their expression of Nrf2, heme oxygenase 1 (HO1), NAD(P)Hquinone-oxidoreductase-1(NQO1), total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px).

4.11. Agrimonia pilosa

In turn, Li et al. [56] conducted an experiment with a DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis to evaluate the effects of Agrimonia pilosa against NLRP3 activation. The results showed that during the IBD occurrence, the models presented decreased expression levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, p65, p-p65, ASC, caspase-1, NF-kB, and NLRP3.

4.12. Vitis vinifera

Sheng et al. [57] in an in vivo study with a DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis, experimented to assess the roles of Vitis vinifera against NLRP3 activation in this model of IBD. The seed proanthocyanidin extract promoted decreases in the expression levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1, and MDA. In addition, the results demonstrated an increased expression of IL-10, SOD, and GSH.

4.13. Lycium ruthenicum Murray

Zong et al. [58] evaluated the roles of Lycium ruthenicum Murray against NLRP3 activation in a DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis. The results demonstrated that the treated animals presented decreased expression levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17A, IFN-γ, TLR4, p-IκB, NF-κB, p65, p-p65, c-Jun, p-signaling transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), induced nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), nitric oxide (NO), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), p38 phosphorylation, ERK phosphorylation, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) phosphorylation, NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1, IL-1β, ROS, and MDA, as well as increased expression levels of IL-10, CAT, SOD, and GSH.

5. Phytochemicals That Target NLRP3 Inflammasome

5.1. Artemisitene

In an experimental study with in vitro and in vivo models of colitis, Hua et al. [59] used artemisitene, a derivative of artemisinin from Artemisia annua plant, against NLRP3 activation in IBD. The results showed that with the treatment, the LPS, nigericin, or ATP-stimulated J774A.1 cells and LPS, nigericin, NLR family CARD domain containing 4 (NLRC4), and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)-stimulated BMDMs cells presented decreased IL-1β, NLRP3-mediated IL-1β secretion, NF-κB-dependent TNF-α activation, pro-caspase-1 cleavage, the interaction between NLRP3 and ASC, ASC oligomerization, ASC specks, NLRP3-ASC binding, NLRC4, AIM2, and IL-6. In addition, the DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice showed decreased IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 serum levels.

5.2. Morroniside

S. Zhang et al. [60] studied LPS-stimulated NCM460 cells in vitro to evaluate the effects of morroniside, an iridoid glycoside derived from Cornus offinalis, against NLRP3 activation during this model of IBD. The results showed that with the treatment, the cells presented regulation of the NLRP3 activation through decreased BCL-2-associated X-protein (BAX), TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, MDA, and MPO expressions, NLRP3 signaling and p-p65–p65 and p-IκBα–IκBα expressions, as well as increased B-cell lymphoma protein 2 (BCL-2), SOD, and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) expressions.

5.3. Protopine

In an in vitro study with LPS-stimulated NCM460 cells, J. Li et al. [61] evaluated the roles of protopine, a derivative of the poppy, berberi, walnut, and buttercup families, against this model of IBD. The results showed that, with the treatment, the cells controlled NLRP3 activation through decreased BAX, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MDA, MPO, ROS, intracellular Ca2+ concentration, NLRP3 signaling, p-IκBα/IκBα, and p-P65/P65, as well as increased BCL-2, T-AOC, SOD, and mitochondrial membrane potential.

5.4. Ferulic Acid

Yu et al. [62] proposed ferulic acid, a phenolic compound derived from diverse fruits and vegetables, as an effective treatment against NLRP3 activation in IBD both in vitro and in vivo. The results showed that with the treatment, the TNF-α-stimulated HIMECs cells presented decreased IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, caspase-1, caspase-3, BCL-2, and thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP)/NLRP3 levels. In addition, the TNBS-induced Sprague-Dawley mice model of colitis presented decreased IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, caspase-1, caspase-3, TXNIP, and NLRP3 levels.

5.5. Artemisinin Analog SM934

Shao et al. [63] innovated using the artemisinin analog SM934, which is water soluble and isolated from Artemisia annua, as an effective treatment against NLRP3 signaling activation in IBD both in vitro and in vivo. After treatment, the TNF-α-stimulated Caco-2 and HT-29 cells presented decreased c-Casp3, NLRP3, claudin-2, ASC, c-Casp1, IL-18, p-NF-κB, p-p38, p-ERK, p-JNK, GSDMD, GSDMD-F, and GSDMD-N, as well as increased E-cadherin, ZO-1, and occludin. In addition, the TNBS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis presented decreased c-Casp3, BAX/BCL-2, c-Casp9, NLRP3, ASC, c-Casp1, GSDMD, IL-18, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), NF-κB, ERK, p38, and JNK.

5.6. Betaine

Chen et al. [64] evaluated the roles of betaine, a bioactive compound richly found in sugar beet, against NLRP3 activation during the DSS-induced C57BL/6J mice model of colitis. After the treatment, the animals presented increased occludin, ZO-1, Nrf2, CAT, and SOD expression levels and decreased MDA, MPO, NOS-related enzymes, COX2, and NLRP3, respectively, ASC, c-Casp1, and N-terminal GSDMD.

5.7. N-Palmitoyl-D-glucosamine

In an in vivo study with dinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (DNBS)-induced C57BL/6J mice model of colitis, Palenca et al. [65] evaluated the roles of N-palmitoyl-D-glucosamine, a natural amide of palmitic acid and glucosamine that belongs to the ALIAmide (autacoid local injury antagonist) family, against this model of IBD. As a result, the animals presented elevated occludin and ZO-1 expression levels and decreased TLR-4, NLRP3, iNOS, IL-1β, and PGE2 expression levels.

5.8. Moronic Acid

In an in vitro and in vivo study using IFN-γ-stimulated intestinal macrophages and DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis, respectively, Ruan and Zha [66] assessed the roles of moronic acid against a triterpenoid richly found in Pistacia chinensis, against NLRP3 activation during IBD. The results showed that with treatment, the cells expressed decreased TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, ROS, CD11, NF-kB (P50), NLRP3, p-P50, and M1 macrophage polarization. In addition, the animals presented with treatment-decreased levels of ROS, CD11, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, ZO-1, NLRP3, and p-P50.

5.9. Munronoid I

Ma et al. [67] studied LPS/ATP-stimulated mouse peritoneal macrophages and BMDMs cells in vitro and DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice colitis model in vivo to evaluate the effects of munronoid I, a diterpenoid richly extracted from the Meliaceae family, against NLRP3 activation during IBD. The treated cells presented decreased expression levels of caspase-1 p20, IL-1β, IL-18, NLRP3, and GSDMD p30. In addition, the treated animals showed reduced expression levels of NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1 (p20), pyroptosis-related protein cleaved GSDMD (p30), IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-18.

5.10. Sanguinarine

Studying LPS-induced THP-1 cells in vitro and DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis in vivo, X. Li et al. [68] assessed the effects of sanguinarine, a benzophenanthridine that belongs to the group of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids and is extracted from Argemone mexicana L., Chelidonium majus L., Macleaya cordata (Willd.) R. Br., Sanguinaria canadensis L. and Bocconia frutescens L., against NLRP3 activation during IBD. The results showed that the treated cells presented decreased expression levels of NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-1β, ROS, and IL-18. In addition, the treated animals presented decreased expression levels of NLRP3, caspase-1, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-13, and IL-18, as well as increased levels of IL-4 and IL-10.

5.11. 8-Oxypalmatine

Cheng et al. [69] studied the effects of 8-oxypalmatine, an isoquinoline alkaloid derived from Fibraureae caulis, in a DSS-induced ulcerative colitis mice model. After the intervention, a reversal of the pattern of inflammatory mediators’ expression and secretion was observed, with a decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-6. There was also an increase in the expression and secretion of the anti-inflammatory IL-10 and antioxidant enzymes such as T-AOC, SOD, GSH, CAT, and GSH-Px. At least, there was decreased messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) expression of NLRP3, ASC, and Caspase-1.

5.12. Quercetin

H. X. Zhang et al. [70] evaluated the roles of quercetin, a bioactive compound richly found in many plants’ flowers, leaves, and fruits, against NLRP3 activation in IBD. The results showed that among treated LPS-induced rat intestinal microvascular endothelial cells (RIMVECs) in vitro, quercetin effectively reduced their expression of TLR4, NLRP3, caspase-1, GSDMD, IL-1β, IL-18, IL-6, and TNF-α.

5.13. Picroside II

Yao et al. [71] conducted a study that evaluated the effects of picroside II, a flavonoid compound extracted from the traditional Chinese medicinal herb Picrorhiza scrophulariiflora, in DSS-induced colitis in C57BL/6 mice and LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells. The treatment showed that picroside II could decrease the expression and secretion levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-a, IL-6, and IL-1β both in vivo and in vitro, and reduce the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome and the activation of the NF-kB.

5.14. Hydroxytyrosol

Miao et al. [72] evaluated the role of hydroxytyrosol, a phenolic compound extracted from olive oil and olive leaves, in a mice model of DSS-induced colitis. After treatment, the models showed improvement in the inflammatory and oxidative profiles, modulation of the intestinal microbiota, and less activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, measured by decreased mRNA transcription of NLRP3 inflammasome proteins.

5.15. SCLP

Pan et al. [73] studied the benefits of SCLP, a pectic polysaccharide purified from Smilax china L., on DSS-induced UC in vivo. With the treatment, there was a decrease in the inflammatory activity, with a decline in the expression and secretion of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, MPO, Gal-3 protein and, consequently, lower expression of the NLRP3, ASC, and Caspase-1 proteins and, therefore, lower activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

5.16. Dioscin

Cai et al. [74] conducted an in vivo study to observe the effects of dioscin, a natural steroidal saponin derived from plants of the genus Dioscoreaceae, on DSS-induced UC in rats. Treatment with dioscin promoted a change in the pattern of macrophages to M2, with consequent improvement in the pro-inflammatory cytokines’ profile. There was a reduction in the expression and secretion of TNF-α and IL-1β pro-inflammatory mediators and an increase in the IL-10. Dioscin also suppressed the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and the expression of MAPKp38 and NF-κBp65 proteins.

5.17. Bryodulcosigenin

Li et al. [75] evaluated the potential of bryodulcosigenin, a cucurbitacin-type triterpenoid isolated from Bryonia roots, both in vitro and in vivo. The authors used TNF-α-stimulated NCM460 cells and a DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis. After treatment, the models showed a decrease in the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome with a consequent decrease in the expression and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and apoptosis-related proteins and an increase in the expression of the epithelial occludin and ZO-1.

5.18. Rosmarinic Acid

Marinho et al. [76] conducted an in vivo study to evaluate the action of rosmarinic acid, a natural polyphenol found in the Labiatae family of herbs, in DSS-induced UC in C57BL/6 mice. The treatment showed that rosmarinic acid decreased the expression and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, decreased MPO activity, promoted activation of the Nrf2 antioxidant pathways, and decreased the expression of NLRP3-related inflammasome proteins.

5.19. Mogrol

Liang et al. [77] studied the activity of mogrol, an active component of Luo Han Guo, in DSS-induced colitis in C57BL/6 mice, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-stimulated THP-1 cells, and LPS-stimulated THP-M cells. Mogrol treatment decreased the expression and secretion of IL-1β and IL-17 pro-inflammatory cytokines, increased IL-10, occludin, and ZO-1, and decreased NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IκBα degradation in vivo. Additionally, there was increased occludin and ZO-1 in vitro, increased expression of BCL-2/BAX, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation, and suppressed caspase-1 activation.

5.20. Sinapic Acid

Qjan et al. [78] evaluated the role of sinapic acid, a naturally occurring hydroxycinnamic acid widely found in vegetables, fruits, cereals, and nuts, in a DSS-induced model of UC. The results showed that the treatment reduced the expression and release of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-17α, and IFN-γ while increasing the levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-10. The treatment also elevated the model’s antioxidant activity by elevating SOD, GSH-Px, CAT, and GSH antioxidant enzymes and reducing MDA. Sinapic acid also promoted an increase in claudin-1, occludin, and ZO-1 proteins and, finally, decreased the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome with a decrease in NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 proteins expression.

5.21. Evodiamine

Ding et al. [79] studied human THP-1 cells stimulated by LPS in vitro and DSS-induced C57BL/6J mice model of colitis in vivo to evaluate the effects of evodiamine, a bioactive compound richly found in the fruits of Evodiae fructus, against NLRP3 activation during IBD. After treatment, the cells presented decreased expression levels of IL-1β, IL-18, caspase1, ASC, ASC oligomers, and P62, and the animals presented decreased expression levels of MPO, IL-1β, IL-18, caspase1, ASC, p-P65NFκB, p-IκB, and P62. After treatment, both in vitro and in vivo models expressed increased levels of microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3), as well as decreased levels of NLRP3 inflammasome assembly.

5.22. Geniposide

Pu et al. [80] studied geniposide, the main active ingredient extracted from Gardenia jasminoides, against NLRP3 activation during the following LPS-stimulated BMDM cells and RAW264.7 macrophages in vitro and DSS-induced C57BL/6J mice in vivo models of IBD. After treatment, the cells presented decreased expression levels of IL-1β and caspase-1, and the animals presented decreased expression levels of MPO, IL-1β, IL-17, TNF-α, IFN-γ, caspase-1, nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2) mRNA, and Arg1 mRNA. In addition, both in vitro and in vivo models presented reduced NLRP3 inflammasome pathway activation.

5.23. Chlorogenic Acid

Zeng et al. [81] studied LPS/ATP-induced RAW264.7 macrophages in vitro and DSS-induced BALB/c mice colitis model in vivo to evaluate the roles of chlorogenic acid, an active dietary polyphenol richly found in honeysuckle, Eucommia and Chaenomeles Lagenaria, against NLRP3 activation during IBD. The results showed that after treatment, both in vitro and in vivo models presented decreased expression levels of IL-1β, IL-18, NLRP3, ASC, caspase1 p45, caspase1 p20, NF-kB, and micro ribonucleic acid 155 (MiR-155).

5.24. Resveratrol

Sun et al. [82] studied the protective effect of resveratrol, a natural non-flavonoid polyphenol significantly present in grapes and wine, against radiation-induced IBD via NLRP-3 inflammasome repression in C57/6 mice. After treatment, the animals presented decreased NLRP3, Sirt1, IL-1β, and TNF-α expression levels.

5.25. Ginsenoside Rk3

Tian et al. [83] studied the effects of ginsenoside Rk3, a bioactive compound richly found in ginseng, against NLRP3 activation during a DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model colitis. The results showed that after treatment, the animals presented decreased NLRP3, ASC, caspase1, MPO, iNOS, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 expression levels and increased claudin 1, occludin, and ZO-1.

5.26. Physalin B

Zhang et al. [84] studied physalin B, a main active withanolide in Physalis alkekengi L. var. franchetii (Mast.) Makino, against NLRP3 during LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages in vitro and DSS-induced BALB/c mice model of acute colitis in vivo models of IBD. The results showed that, after treatment, the cells presented decreased IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α expression levels, and the animals showed decreased NLRP3, ASC, IL-1β, MPO, TNF-α, IL-6, NF-κB activation cascade and STAT3 expression levels and β-arrestin one signaling pathway activation.

5.27. Oroxindin

Liu et al. [85] studied the effects of oroxindin, a flavonoid isolated from the traditional Chinese medicine Huang-Qin, against NLRP3 activation during LPS-stimulated human THP-1 cells in vitro and DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of acute colitis in vivo models of IBD. The results showed that after treatment, the cells and animals presented decreased levels of NLRP3, IL-1β, caspase1, and IL-18.

5.28. Resveratrol Analog 2-Methoxyl-3,6-dihydroxyl-IRA

Chen et al. [86] studied the effects of the synthetic imine Resveratrol Analog 2-Methoxyl-3,6-Dihydroxyl-IRA against NLRP3 activation during human colon cancer LS174T and Caco2 cells in vitro and DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis in vivo models of IBD. The results showed that after treatment, both in vitro and in vivo models presented decreased levels of NLRP3, TNF-α, and IL-6 expression levels and increased Nrf2, aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C (AKR1C), NQO1, and GSH.

5.29. Curcumin

Gong et al. [87] studied LPS-primed peritoneal macrophages in vitro and DSS-induced C57BL/6 mice model of colitis in vivo to evaluate the roles of curcumin, a bioactive phenolic compound richly found in Curcuma longa, against NLRP3 activation during these models of IBD. The results showed that after treatment, the cells presented decreased levels of IL-1β, ROS production, and cathepsin B leakage and increased levels of K+ efflux. In turn, after treatment, the animals presented decreased NLRP3, IL-1β, ASC, ROS, cathepsin B leakage, caspase1, MPO, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and IL-6 levels and increased K+ efflux. figure 2 illustrates the NLRP3 regulation with the use of curcumin.

figure 2. NLRP3 inflammasome regulation with the use of curcumin. AIM2, Interferon-Inducible Protein AIM2; ATP, Adenosine Triphosphate; DAMPs, Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns; hsp70, Heat Shock Protein 70; hsp90, Heat Shock Protein 90; IL, Interleukin; NF-kB, Nuclear Factor Kappa b; NLR, Nod-like Receptor; NLRC5, NOD-like receptor family CARD domain containing 4; NLRC5, NOD-like receptor family CARD domain containing 5; NLRP1b, NLR family pyrin domain containing 1b; NLRP3, Nod-like Receptor Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3.

References

- Kevans, D.; Silverberg, M.S.; Borowski, K.; Griffiths, A.; Xu, W.; Onay, V.; Paterson, A.D.; Knight, J.; Croitoru, K. IBD Genetic Risk Profile in Healthy First-Degree Relatives of Crohn’s Disease Patients. J. Crohns Colitis 2016, 10, 209–215.

- Aniwan, S.; Santiago, P.; Loftus Jr, E.V.; Park, S.H. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia and Asian immigrants to Western countries. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2022, 10, 1063–1076.

- Du, L.; Ha, C. Epidemiology and Pathogenesis of Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 49, 643–654.

- Kaenkumchorn, T.; Wahbeh, G. Ulcerative Colitis: Making the Diagnosis. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 49, 655–669.

- Adams, S.M.; Bornemann, P.H. Ulcerative colitis. Am. Fam. Physician 2013, 87, 699–705.

- Keshteli, A.H.; Madsen, K.L.; Dieleman, L.A. Diet in the Pathogenesis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis; A Review of Randomized Controlled Dietary Interventions. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1498.

- Ordás, I.; Eckmann, L.; Talamini, M.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sandborn, W.J. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2012, 380, 1606–1619.

- Niv, Y. Hospitalization of Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2021, 23, 186–190.

- Lee, S.D. Health Maintenance in Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 49, xv–xvi.

- Segal, J.P.; LeBlanc, J.F.; Hart, A.L. Ulcerative colitis: An update. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, 135–139.

- Roselli, M.; Finamore, A. Use of Synbiotics for Ulcerative Colitis Treatment. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 15, 174–182.

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, C.Q.; Sang, L.X. Mucosal lesions of the upper gastrointestinal tract in patients with ulcerative colitis: A review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 2963–2978.

- Wehkamp, J.; Stange, E.F. Recent advances and emerging therapies in the non-surgical management of ulcerative colitis. F1000Research 2018, 7, 1207.

- Hashash, J.G.; Picco, M.F.; Farraye, F.A. Health Maintenance for Adult Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr. Treat. Options Gastroenterol. 2021, 19, 583–596.

- Louis, E. Tailoring Biologic or Immunomodulator Treatment Withdrawal in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Med. 2019, 6, 302.

- Carter, M.J.; Lobo, A.J.; Travis, S.P.L. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2004, 53, v1.

- Louis, E. Stopping Anti-TNF in Crohn’s Disease Remitters: Pros and Cons: The Pros. Inflamm. Intest. Dis. 2022, 7, 64–68.

- Petagna, L.; Antonelli, A.; Ganini, C.; Bellato, V.; Campanelli, M.; Divizia, A.; Efrati, C.; Franceschilli, M.; Guida, A.M.; Ingallinella, S.; et al. Pathophysiology of Crohn’s disease inflammation and recurrence. Biol. Direct 2020, 15, 23.

- Veauthier, B.; Hornecker, J.R. Crohn’s Disease: Diagnosis and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2018, 98, 661–669.

- Yang, F.; Ni, B.; Liu, Q.; He, F.; Li, L.; Zhong, X.; Zheng, X.; Lu, J.; Chen, X.; Lin, H.; et al. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental colitis by normalizing the gut microbiota. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 475.

- Torres, J.; Burisch, J.; Riddle, M.; Dubinsky, M.; Colombel, J.F. Preclinical disease and preventive strategies in IBD: Perspectives, challenges and opportunities. Gut 2016, 65, 1061–1069.

- Nadalian, B.; Nadalian, B.; Houri, H.; Shahrokh, S.; Abdehagh, M.; Yadegar, A.; Ebrahimipour, G. Phylogrouping and characterization of Escherichia coli isolated from colonic biopsies and fecal samples of patients with flare of inflammatory bowel disease in Iran. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 985300.

- Atanassova, A.; Georgieva, A. Circulating miRNA-16 in inflammatory bowel disease and some clinical correlations—A cohort study in Bulgarian patients. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 6310–6315.

- Shahini, A.; Shahini, A. Role of interleukin-6-mediated inflammation in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease: Focus on the available therapeutic approaches and gut microbiome. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 17, 55–74.

- Zhao, X.; Yang, W.; Yu, T.; Yu, Y.; Cui, X.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, H.; Yu, Y.; Bilotta, A.J.; Yao, S.; et al. Th17 cell-derived amphiregulin promotes colitis-associated intestinal fibrosis through activation of mTOR and MEK in intestinal myofibroblasts. Gastroenterology 2022, 164, 89–102.

- Askari, H.; Shojaei-Zarghani, S.; Raeis-Abdollahi, E.; Jahromi, H.K.; Abdullahi, P.R.; Daliri, K.; Tajbakhsh, A.; Rahmati, L.; Safarpour, A.R. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Current State of the Art. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2022.

- Yang, J.; Wise, L.; Fukuchi, K.I. TLR4 Cross-Talk With NLRP3 Inflammasome and Complement Signaling Pathways in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 724.

- Wang, L.; Hauenstein, A.V. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Mechanism of action, role in disease and therapies. Mol. Asp. Med. 2020, 76, 100889.

- Silveira Rossi, J.L.; Barbalho, S.M.; Reverete de Araujo, R.; Bechara, M.D.; Sloan, K.P.; Sloan, L.A. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases: Going beyond traditional risk factors. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2022, 38, e3502.

- Jo, E.K.; Kim, J.K.; Shin, D.M.; Sasakawa, C. Molecular mechanisms regulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 148–159.

- Chen, M.Y.; Ye, X.J.; He, X.H.; Ouyang, D.Y. The Signaling Pathways Regulating NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Inflammation 2021, 44, 1229–1245.

- Chen, Q.L.; Yin, H.R.; He, Q.Y.; Wang, Y. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome as new therapeutic avenue for inflammatory bowel disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111442.

- Zhen, Y.; Zhang, H. NLRP3 Inflammasome and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 276.

- Shao, B.Z.; Wang, S.L.; Pan, P.; Yao, J.; Wu, K.; Li, Z.S.; Bai, Y.; Linghu, E.Q. Targeting NLRP3 Inflammasome in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Putting out the Fire of Inflammation. Inflammation 2019, 42, 1147–1159.

- Zhou, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Tang, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; Hu, R. Oroxylin A inhibits colitis by inactivating NLRP3 inflammasome. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 58903–58917.

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, J.; Zhao, L.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Pan, D.; Miao, H.; Guo, Q.; Lu, N. Wogonoside protects against dextran sulfate sodium-induced experimental colitis in mice by inhibiting NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2015, 94, 142–154.

- Liu, W.; Guo, W.; Hang, N.; Yang, Y.; Wu, X.; Shen, Y.; Cao, J.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Q. MALT1 inhibitors prevent the development of DSS-induced experimental colitis in mice via inhibiting NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 30536–30549.

- Zhang, C.; Qin, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, N.; Tan, B.; Siwko, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J.; Qian, M.; et al. ADP/P2Y(1) aggravates inflammatory bowel disease through ERK5-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 13, 931–945.

- Wang, M.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Xie, H. Knockdown of P2Y4 ameliorates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury in mice via inhibiting the activation of the NF-κB/MMP8 axis. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 953977.

- Liang, B.; Wu, C.; Wang, C.; Sun, W.; Chen, W.; Hu, X.; Liu, N.; Xing, D. New insights into bacterial mechanisms and potential intestinal epithelial cell therapeutic targets of inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1065608.

- Zhou, L.; Liu, T.; Huang, B.; Luo, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J.; Leung, D.; Yang, X.; Chan, K.W.; et al. Excessive deubiquitination of NLRP3-R779C variant contributes to very-early-onset inflammatory bowel disease development. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 267–279.

- Rao, Z.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Fang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, S.; et al. Vitamin D Receptor Inhibits NLRP3 Activation by Impeding Its BRCC3-Mediated Deubiquitination. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2783.

- Ngui, I.Q.H.; Perera, A.P.; Eri, R. Does NLRP3 Inflammasome and Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Play an Interlinked Role in Bowel Inflammation and Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer? Molecules 2020, 25, 2427.

- Chen, X.; Liu, G.; Yuan, Y.; Wu, G.; Wang, S.; Yuan, L. NEK7 interacts with NLRP3 to modulate the pyroptosis in inflammatory bowel disease via NF-κB signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 906.

- Song, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Rong, L.; Wang, B.; Zhang, N. Biological functions of NLRP3 inflammasome: A therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2021, 60, 61–75.

- Dai, Y.; Lu, Q.; Li, P.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, T.; Hu, Y.; Ding, K.; Zhao, M. Xianglian Pill attenuates ulcerative colitis through TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 300, 115690.

- Wong, W.T.; Wu, C.H.; Li, L.H.; Hung, D.Y.; Chiu, H.W.; Hsu, H.T.; Ho, C.L.; Chernikov, O.V.; Cheng, S.M.; Yang, S.P.; et al. The leaves of the seasoning plant Litsea cubeba inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome and ameliorate dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 871325.

- Hong, F.; Zhao, M.; Xue, L.L.; Ma, X.; Liu, L.; Cai, X.Y.; Zhang, R.J.; Li, N.; Wang, L.; Ni, H.F.; et al. The ethanolic extract of Artemisia anomala exerts anti-inflammatory effects via inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome. Phytomedicine 2022, 102, 154163.

- Bian, Z.; Qin, Y.; Li, L.; Su, L.; Fei, C.; Li, Y.; Hu, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Mao, C.; et al. Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. Protects against DSS-induced colitis in mice: Involvement of TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway and gut microbiota. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 298, 115570.

- Yan, S.; Wang, P.; Wei, H.; Jia, R.; Zhen, M.; Li, Q.; Xue, C.; Li, J. Treatment of ulcerative colitis with Wu-Mei-Wan by inhibiting intestinal inflammatory response and repairing damaged intestinal mucosa. Phytomedicine 2022, 105, 154362.

- Xue, S.; Xue, Y.; Dou, D.; Wu, H.; Zhang, P.; Gao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, Z.; Yang, S.; Gu, S. Kui Jie Tong Ameliorates Ulcerative Colitis by Regulating Gut Microbiota and NLRP3/Caspase-1 Classical Pyroptosis Signaling Pathway. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 2782112.

- Sudeep, H.V.; Venkatakrishna, K.; Raj, A.; Reethi, B.; Shyamprasad, K. Viphyllin™, a standardized extract from black pepper seeds, mitigates intestinal inflammation, oxidative stress, and anxiety-like behavior in DSS-induced colitis mice. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14306.

- Salama, R.M.; Darwish, S.F.; El Shaffei, I.; Elmongy, N.F.; Fahmy, N.M.; Afifi, M.S.; Abdel-Latif, G.A. Morus macroura Miq. Fruit extract protects against acetic acid-induced ulcerative colitis in rats: Novel mechanistic insights on its impact on miRNA-223 and on the TNFα/NFκB/NLRP3 inflammatory axis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 165, 113146.

- Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, X.; Xu, B.; Chen, L.; Chen, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, Z. Therapeutic effect of Patrinia villosa on TNBS-induced ulcerative colitis via metabolism, vitamin D receptor and NF-κB signaling pathways. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 288, 114989.

- Dai, W.; Zhan, X.; Peng, W.; Liu, X.; Peng, W.; Mei, Q.; Hu, X. Ficus pandurata Hance Inhibits Ulcerative Colitis and Colitis-Associated Secondary Liver Damage of Mice by Enhancing Antioxidation Activity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 2617881.

- Li, C.; Wang, M.; Sui, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, W. Protective mechanisms of Agrimonia pilosa Ledeb in dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis as determined by a network pharmacology approach. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2021, 53, 1342–1353.

- Sheng, K.; Zhang, G.; Sun, M.; He, S.; Kong, X.; Wang, J.; Zhu, F.; Zha, X.; Wang, Y. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis through intestinal barrier improvement, oxidative stress reduction, and inflammatory cytokines and gut microbiota modulation. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 7817–7829.

- Zong, S.; Yang, L.; Park, H.J.; Li, J. Dietary intake of Lycium ruthenicum Murray ethanol extract inhibits colonic inflammation in dextran sulfate sodium-induced murine experimental colitis. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 2924–2937.

- Hua, L.; Liang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, X.; Cai, H.; Liu, Z.; Ou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Yan, Y.; et al. Artemisinin-derived artemisitene blocks ROS-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome and alleviates ulcerative colitis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 113, 109431.

- Zhang, S.; Lai, Q.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J. Morroniside alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory and oxidative stress in inflammatory bowel disease by inhibiting NLRP3 and NF-κB signaling pathways. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2022, 50, 93–99.

- Li, J.; Xu, Z.; OuYang, C.; Wu, X.; Xie, Y.; Xie, J. Protopine alleviates lipopolysaccharide-triggered intestinal epithelial cell injury through retarding the NLRP3 and NF-κB signaling pathways to reduce inflammation and oxidative stress. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2022, 50, 84–92.

- Yu, S.; Qian, H.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, Z. Ferulic acid relieved ulcerative colitis by inhibiting the TXNIP/NLRP3 pathway in rats. Cell Biol. Int. 2022, 47, 417–427.

- Shao, M.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, F.; Yang, X.; Qi, Q.; Yang, F.; Hao, T.; Lin, Z.; He, P.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Artemisinin analog SM934 alleviates epithelial barrier dysfunction via inhibiting apoptosis and caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis in experimental colitis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 849014.

- Chen, L.; Liu, D.; Mao, M.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Cao, W.; Zhong, X. Betaine Ameliorates Acute Sever Ulcerative Colitis by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress Induced Inflammatory Pyroptosis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, e2200341.

- Palenca, I.; Seguella, L.; Del Re, A.; Franzin, S.B.; Corpetti, C.; Pesce, M.; Rurgo, S.; Steardo, L.; Sarnelli, G.; Esposito, G. N-Palmitoyl-D-Glucosamine Inhibits TLR-4/NLRP3 and Improves DNBS-Induced Colon Inflammation through a PPAR-α-Dependent Mechanism. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1163.

- Ruan, S.; Zha, L. Moronic acid improves intestinal inflammation in mice with chronic colitis by inhibiting intestinal macrophage polarization. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022, 36, e23188.

- Ma, X.; Di, Q.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, R.; Xiao, Y.; Li, X.; Wu, H.; Tang, H.; Quan, J.; et al. Munronoid I Ameliorates DSS-Induced Mouse Colitis by Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Pyroptosis Via Modulation of NLRP3. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 853194.

- Li, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, Q.; Xu, W.; Zhao, Q.; Xu, N.; Hu, X.; Ye, Z.; Yu, S.; Liu, J.; et al. Sanguinarine ameliorates DSS induced ulcerative colitis by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and modulating intestinal microbiota in C57BL/6 mice. Phytomedicine 2022, 104, 154321.

- Cheng, J.; Ma, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Li, M.; Ai, G.; Zhan, R.; Xie, J.; Su, Z.; Huang, X. 8-Oxypalmatine, a novel oxidative metabolite of palmatine, exhibits superior anti-colitis effect via regulating Nrf2 and NLRP3 inflammasome. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113335.

- Zhang, H.X.; Li, Y.Y.; Liu, Z.J.; Wang, J.F. Quercetin effectively improves LPS-induced intestinal inflammation, pyroptosis, and disruption of the barrier function through the TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway in vivo and in vitro. Food Nutr. Res. 2022, 66.

- Yao, H.; Yan, J.; Yin, L.; Chen, W. Picroside II alleviates DSS-induced ulcerative colitis by suppressing the production of NLRP3 inflammasomes through NF-κB signaling pathway. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2022, 44, 437–446.

- Miao, F. Hydroxytyrosol alleviates dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and modulating gut microbiota in vivo. Nutrition 2022, 97, 111579.

- Pan, X.; Wang, H.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, X.; Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y. Pectic polysaccharide from Smilax china L. ameliorated ulcerative colitis by inhibiting the galectin-3/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 277, 118864.

- Cai, J.; Liu, J.; Fan, P.; Dong, X.; Zhu, K.; Liu, X.; Zhang, N.; Cao, Y. Dioscin prevents DSS-induced colitis in mice with enhancing intestinal barrier function and reducing colon inflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 99, 108015.

- Li, R.; Chen, C.; Liu, B.; Shi, W.; Shimizu, K.; Zhang, C. Bryodulcosigenin a natural cucurbitane-type triterpenoid attenuates dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice. Phytomedicine 2022, 94, 153814.

- Marinho, S.; Illanes, M.; Ávila-Román, J.; Motilva, V.; Talero, E. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Rosmarinic Acid-Loaded Nanovesicles in Acute Colitis through Modulation of NLRP3 Inflammasome. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 162.

- Liang, H.; Cheng, R.; Wang, J.; Xie, H.; Li, R.; Shimizu, K.; Zhang, C. Mogrol, an aglycone of mogrosides, attenuates ulcerative colitis by promoting AMPK activation. Phytomedicine 2021, 81, 153427.

- Qian, B.; Wang, C.; Zeng, Z.; Ren, Y.; Li, D.; Song, J.L. Ameliorative Effect of Sinapic Acid on Dextran Sodium Sulfate- (DSS-) Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Kunming (KM) Mice. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 8393504.

- Ding, W.; Ding, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Cao, W.; Du, R. Evodiamine Attenuates Experimental Colitis Injury Via Activating Autophagy and Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome Assembly. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 573870.

- Pu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Xu, M.; Xie, H.; Zhao, J. Using Network Pharmacology for Systematic Understanding of Geniposide in Ameliorating Inflammatory Responses in Colitis Through Suppression of NLRP3 Inflammasome in Macrophage by AMPK/Sirt1 Dependent Signaling. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2020, 48, 1693–1713.

- Zeng, J.; Zhang, D.; Wan, X.; Bai, Y.; Yuan, C.; Wang, T.; Yuan, D.; Zhang, C.; Liu, C. Chlorogenic Acid Suppresses miR-155 and Ameliorates Ulcerative Colitis through the NF-κB/NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, e2000452.

- Sun, H.; Cai, H.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ji, K.; Du, L.; Xu, C.; Tian, L.; He, N.; Wang, J.; et al. The Protection Effect of Resveratrol Against Radiation-Induced Inflammatory Bowel Disease via NLRP-3 Inflammasome Repression in Mice. Dose Response 2020, 18, 1559325820931292.

- Tian, M.; Ma, P.; Zhang, Y.; Mi, Y.; Fan, D. Ginsenoside Rk3 alleviated DSS-induced ulcerative colitis by protecting colon barrier and inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 85, 106645.

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, N.; Hu, X.; Zheng, Y. Anti-colitic effects of Physalin B on dextran sodium sulfate-induced BALB/c mice by suppressing multiple inflammatory signaling pathways. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 259, 112956.

- Liu, Q.; Zuo, R.; Wang, K.; Nong, F.F.; Fu, Y.J.; Huang, S.W.; Pan, Z.F.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, X.; Deng, X.L.; et al. Oroxindin inhibits macrophage NLRP3 inflammasome activation in DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice via suppressing TXNIP-dependent NF-κB pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 771–781.

- Chen, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Li, C.; Pan, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, X.J. Synthetic Imine Resveratrol Analog 2-Methoxyl-3,6-Dihydroxyl-IRA Ameliorates Colitis by Activating Protective Nrf2 Pathway and Inhibiting NLRP3 Expression. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 7180284.

- Gong, Z.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, J.; Yan, J.; Wang, L.; Du, X.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Cai, W.; Wu, J. Curcumin alleviates DSS-induced colitis via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammsome activation and IL-1β production. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 104, 11–19.

More

Information

Subjects:

Integrative & Complementary Medicine

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Entry Collection:

Gastrointestinal Disease

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

15 Jun 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No