Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Violeta Diana Oprea | -- | 1797 | 2023-05-15 11:14:38 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | Meta information modification | 1797 | 2023-05-16 02:52:29 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Marinescu, M.; Oprea, V.D.; Nechita, A.; Tutunaru, D.; Nechita, L.; Romila, A. Brain Natriuretic Peptide in Geriatric Heart Failure Evaluation. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/44294 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Marinescu M, Oprea VD, Nechita A, Tutunaru D, Nechita L, Romila A. Brain Natriuretic Peptide in Geriatric Heart Failure Evaluation. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/44294. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Marinescu, Mihai, Violeta Diana Oprea, Aurel Nechita, Dana Tutunaru, Luiza-Camelia Nechita, Aurelia Romila. "Brain Natriuretic Peptide in Geriatric Heart Failure Evaluation" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/44294 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Marinescu, M., Oprea, V.D., Nechita, A., Tutunaru, D., Nechita, L., & Romila, A. (2023, May 15). Brain Natriuretic Peptide in Geriatric Heart Failure Evaluation. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/44294

Marinescu, Mihai, et al. "Brain Natriuretic Peptide in Geriatric Heart Failure Evaluation." Encyclopedia. Web. 15 May, 2023.

Copy Citation

Heart failure is one of the main morbidity and mortality factors in the general population and especially in elderly patients. Natriuretic peptides, in particular B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and its fraction NTproBNP, have gained an increasingly important role in the screening, diagnosis and treatment of heart failure.

heart failure in geriatric population

natriuretic peptides in heart failure

BNP

NTproBNP

1. Introduction

Heart failure is one of the main morbidity and mortality factors in the general population and especially in elderly patients. Thus, at the European level, the prevalence of heart failure is 1% in people under 55 years of age but increases to over 10% in people over 70 years of age [1].

With life expectancy increasing to an average of 73 years, the geriatric population is becoming increasingly representative, leading to an increasing incidence of heart failure. In recent years, in developed countries, heart failure has become a growing public health problem, generating higher costs for the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of these patients [2][3][4][5][6].

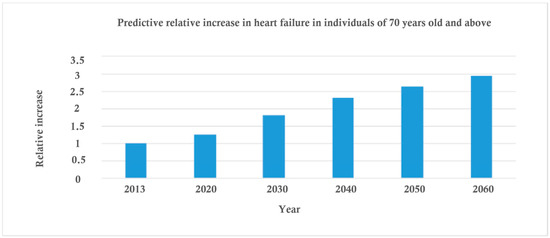

Advances in medicine, easier access to medical and care services have led to an increase in the elderly population and consequently its share of heart failure cases. More than a quarter of heart failure patients are over 80 years of age, and among decompensated cases requiring emergency hospitalization, about 1 in 7 are over 80 [7][8][9][10][11][12][13]. As you can see in Figure 1, the predictions are that heart failure in the elderly will more than double by 2040 and triple by 2060 (heart failure in the elderly is set to triple by 2060, according to new data from the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility (AGES)—Reykjavík study presented at ESC Congress 2016) [5][6][14][15][16].

Age plays an important role in the deterioration of cardiovascular function, thus the risk of cardiovascular disease among the geriatric population is very high. The prevalence of cardiovascular disease increases with age [5][6][16][17][18]. For example, The American Heart Association reported an incidence of heart disease of 40% at ages between 40–59 years, increasing to 75% at the ages of 60–79 years and reaching 86% for people over 80 years old [19][20][21]. All over the world, the geriatric population poses a great burden on health care systems because of the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease and especially heart failure among them. This burden, reflected in higher costs of treatment, hospitalization and rehabilitation, is directly correlated with the increase in morbidity, frailty and mortality among the elderly. Taking these facts into consideration and the prediction of the rise of the elderly population by 2–3 times until the year 2050 [1][14], the necessity of better understanding the etiology and physiopathology of cardiovascular disease is essential [7][8][9][10][11][12][13][22].

2. The Use of Brain Natriuretic Peptide in the Evaluation of Heart Failure in Geriatric Patients

Elderly patients are under-represented in clinical trials on the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure. These studies underlie the development of treatment guidelines and form the foundation of modern evidence-based medicine. On average, less than 30% of the patients selected in these clinical trials were over 70 years of age. Many of these patients are excluded from clinical trials because of comorbidities.

The particularities of the elderly patient, which make the management of heart failure difficult, are the presence of comorbidities, frailty, cognitive impairment and polypharmacy [7][8][9][10][11][12][23][24][25].

Approximately 60% of elderly patients with heart failure have at least three comorbidities. Among these comorbidities, the most common are hypertension and heart rhythm disorders, and among non-cardiac conditions these include chronic renal failure, diabetes mellitus and anemia [2]. All these comorbidities make the geriatric patient a complex case, which has an impact on the diagnosis and treatment algorithm of heart failure in these patients.

Although the benefits of standard therapies in heart failure, as evidenced by subgroup analyses in clinical trials, are present in the elderly population, these drugs have been found to still be underutilized [1][14][26][27]. This is mainly due to contraindications as well as the risk of adverse reactions. Elderly patients are more prone to adverse reactions, being more vulnerable due to comorbidities and frailty. The TIME-CHF trial (Trial of Intensified versus Standard Medical Therapy in Elderly Patients with Congestive Heart Failure) studied the titration of specific medication according to serum natriuretic peptide levels in patients over 60 years of age, without demonstrating benefits in patients over 75 years of age [28]. However, geriatric patients receive suboptimal doses of medication. On the other hand, the optimal doses of drugs that are proven by clinical trials to improve the survival of patients with heart failure are generally chosen by individual clinicians according to the patient’s symptoms and clinical signs. These subjective criteria often lead to medication under-dosing, so target doses are rarely reached. Hence the need for objective indices to guide heart failure therapy.

In addition to drug treatment, heart failure requires invasive interventions on the heart, such as coronary angiography followed by possible coronary revascularization by percutaneous angioplasty or coronary artery bypass grafting, pacemaker implantation, intramyocardial resynchronization devices, intracardiac defibrillator and radiofrequency ablation for heart rhythm disorders. All of these therapies lead to improved quality of life and survival, but the decision to perform them on an individual geriatric patient requires a thorough assessment. This requires multidisciplinary teams of cardiologists, neurologists, geriatricians, psychiatrists, etc. Assessment of comorbidities, frailty, life expectancy, risk/benefit ratio, etc., must be taken into account [5][6][15][16][17][18][29]. Although these interventions have proven beneficial effects, European registries show an under-use of them in elderly patients, so that about 30% of intramyocardial resynchronization devices have been implanted in patients over 75 years of age, and a Spanish registry shows a 15% share of patients over 75 years of age in intracardiac defibrillator implantation [14]. Again, objective indices (biomarkers) are needed to stratify prognosis and cardiovascular risk in order to guide the medical team in making an appropriate therapeutic decision for each individual patient.

The main symptoms of heart failure, such as exercise intolerance and dyspnea, can also be interpreted in the context of older age and the functional disability of geriatric patients, which is why the diagnosis of heart failure may be overlooked.

In a study of the distribution of risk factors for the development of heart failure according to age, a higher proportion of known classical risk factors was found in the younger population compared to the elderly. In other words, traditional predictors of heart failure were less common in elderly patients. For example, the presence of smoking as a risk factor was 21% in younger patients versus 13% in older patients and diabetes was present in 14% of younger patients versus 7% of geriatric patients [30][31][32].

Under these conditions, there is a growing interest in developing effective methods for the diagnosis, screening, prognosis and treatment guidance of heart failure. These methods need to be as specific and sensitive as possible to be clinically relevant.

Although the scientific data on the etiology and pathophysiology of heart failure are substantial, the imaging methods used are increasingly more powerful with high sensitivity, and diagnostic criteria are constantly being revised in guidelines for medical practice.

The concept of biochemical tests, using various biomarkers such as natriuretic peptides and troponin, is increasingly taking shape in current clinical trials.

The diagnosis of heart failure is based on the patient’s clinical history, the physical examination of the patient performed by the doctor and the results of the complementary imaging tests: chest radiography and echocardiography. About 30–50% of patients presenting in emergency departments for decompensated heart failure are misdiagnosed, because of the atypical manifestations, lack of imagery and the clinical signs that are not always obvious [33]. Thus, there is a necessity for new diagnostic tests to help clinicians in the diagnosis of heart failure and make a better differential diagnosis with other diseases with a similar manifestation as heart failure. The correct and timely diagnosis of heart failure would make the initiation of adequate treatment possible, and by doing so would increase the results of the treatment, reduce the hospitalization duration, reduce the costs of therapy and improve prognosis of the patients.

Diagnosis of heart failure, especially in elderly patients, is difficult because symptoms such as fatigue and dyspnea on exertion, as well as clinical signs such as swollen jugular veins or tibial edema, are not specific to heart failure, but may be caused by a range of comorbidities. Differential diagnosis between cardiovascular disease and other pathologies is difficult in geriatric patients.

Additionally, the clinical symptoms and signs of heart failure often become apparent in the later stages of the disease, so diagnosis is made late and the therapeutic benefits are greatly reduced.

As for dyspnea, the most common complaint of patients with heart failure, studies show uncertainty about its etiology. For example, the “Breathing not Properly” study reports diagnostic errors in about half of the cases presented for dyspnea. The difficulty of diagnosing heart failure is even greater in patients presenting for the first time with symptoms of dyspnea. Clinical examination of the patient is often not sufficient in developing an accurate diagnosis, and imaging methods such as chest radiography have neither the necessary sensitivity nor specificity. Echocardiography can detect changes in left ventricular ejection fraction, but for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, it is not as useful.

The need for complementary methods (biomarkers) for differential and early diagnosis of heart failure is becoming more and more evident, even in its subclinical stages. These methods need to have increased specificity and sensitivity and be widely available.

Natriuretic peptides, in particular B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and its fraction NTproBNP, have gained in recent years an increasingly important role in the screening, diagnosis and treatment of heart failure.

The B-type natriuretic peptide is released by myocardial cells in response to increased parietal stress under the conditions of volume or intramyocardial pressure overload that occur in heart failure. BNP has a natriuretic and peripheral vasodilator effect, thus reducing this intramyocardial overload.

Geriatric patients show an increased prevalence of heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction, which makes diagnosis more difficult, especially in the presence of comorbidities and predominant symptoms, such as dyspnea on exertion and reduced functional capacity, which is often attributed to simple ageing. Natriuretic peptides could be useful in the diagnosis of heart failure for this type of patient, but the interpretation of their serum values may be influenced by several factors such as chronic kidney disease, sepsis, hyperthyroidism, chronic anemia, atrial fibrillation and others. All these comorbidities, very common in elderly patients, modifying basal natriuretic peptide values independently of the presence of heart failure lead to the need to establish different cut-off values of these biomarkers in geriatric patients. Age and chronic kidney disease appear to be the major determinants of serum BNP/NTproBNP values. It was also found that even patients without a diagnosis of heart failure, but with elevated serum natriuretic peptide values, showed increased cardiovascular events and mortality. This raises the possibility of using natriuretic peptides to screen for silent heart disease in elderly patients [15][34].

References

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726.

- Wang, T.J. Impact of age and sex on plasma natriuretic peptide levels in healthy adults. Am. J. Cardiol. 2002, 90, 254–258.

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; Falk, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.-P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. 2016 Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. Fail. 2016, 18, 8910975.

- Pinilla, J.M.G.; Díez-Villanueva, P.; Freire, R.B.; Formiga, F.; Marcos, M.C.; Bonanad, C.; Leiro, M.G.C.; García, J.R.; Molina, B.D.; Grau, C.E.; et al. Consensus document and recommendations on palliative care in heart failure of the Heart Failure and Geriatric Cardiology Working Groups of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2020, 73, 69–77.

- Baruch, L.; Glazer, R.D.; Aknay, N.; Vanhaecke, J.; Heywood, J.T.; Anand, I.; Krum, H.; Hester, A.; Cohn, J.N. Morbidity, mortality, physiologic and functional parameters in elderly and non-elderly patients in the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val-HeFT). Am. Heart J. 2004, 148, 951–957.

- Akita, K.; Kohno, T.; Kohsaka, S.; Shiraishi, Y.; Nagatomo, Y.; Izumi, Y.; Goda, A.; Mizuno, A.; Sawano, M.; Inohara, T.; et al. Current use of guideline-based medical therapy in elderly patients admitted with acute heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and its impact on event-free survival. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 235, 162–168.

- Triposkiadis, F.; Xanthopoulos, A.; Butler, J. Cardiovascular aging and heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 804–813.

- Steenman, M.; Lande, G. Cardiac aging and heart disease in humans. Biophys. Rev. 2017, 9, 131–137.

- Abdelhafz, A.H. Heart failure in older people: Causes, diagnosis and treatment. Age Ageing 2002, 31, 29–36.

- Berliner, D.; Bauersachs, J. Drug treatment of heart failure in the elderly. Herz 2018, 43, 207–213.

- Luchner, A.; Behrens, G.; Stritzke, J.; Markus, M.; Stark, K.; Peters, A.; Meisinger, C.; Leitzmann, M.; Hense, H.W.; Schunkert, H.; et al. Long-term pattern of brain natriuretic peptide and N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide and its determinants in the general population: Contribution of age, gender, and cardiac and extra-cardiac factors. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2013, 15, 859–867.

- Komajda, M.; Hanon, O.; Hochadel, M.; Lopez-Sendon, J.L.; Follath, F.; Ponikowski, P.; Harjola, V.P.; Drexler, H.; Dickstein, K.; Tavazzi, L.; et al. Contemporary management of octogenarians hospitalized for heart failure in Europe: Euro Heart Failure Survey II. Eur. Heart J. 2009, 30, 478–486.

- Borlaug, B.A. Evaluation and management of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 559–573.

- Díez-Villanueva, P.; Alfonso, F. Heart failure in the elderly. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 219–232.

- Writing Committee 2021 Update to the 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Optimization of Heart Failure Treatment: Answers to 10 Pivotal Issues About Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 772–810.

- Barywani, S.B.; Ergatoudes, C.; Schaufelberger, M.; Petzold, M.; Fu, M.L. Does the target dose of neurohormonal blockade matter for outcome in systolic heart failure in octogenarians? Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 187, 666–672.

- Azad, N.; Lemay, G. Management of chronic heart failure in the older population. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2014, 11, 329–337.

- Guerra, F.; Brambatti, M.; Matassini, M.V.; Capucci, A. Current therapeutic options for heart failure in elderly patients. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1483873.

- Passino, C.; Poletti, R.; Fontana, M.; Vergaro, G.; Prontera, C.; Gabutti, A.; Giannoni, A.; Emdin, M.; Clerico, A. Clinical relevance of non-cardiac determinants of natriuretic peptide levels. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2008, 46, 1515–1523.

- Van Veldhuisen DJ, B-type natriuretic peptide and prognosis in heart failure patients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 1498–1506.

- Yancy, C.W.; Jessup, M.; Bozkurt, B.; Butler, J.; Casey, D.E.; Drazner, M.H.; Fonarow, G.C.; Geraci, S.A.; Horwich, T.; Januzzi, J.L.; et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, e147–e239.

- Reddy, Y.N.; Carter, R.E.; Obokata, M.; Redfield, M.M.; Borlaug, B.A. A simple, evidence-based approach to help guide diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 2018, 138, 861–870.

- Muscari, A.; Bianchi, G.; Forti, P.; Giovagnoli, M.; Magalotti, D.; Pandolfi, P.; Zoli, M.; Pianoro Study Group. Physical Activity and Other Determinants of Survival in the Oldest Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 402–406.

- Mason, J.M.; Hancock, H.C.; Close, H.; Murphy, J.J.; Fuat, A.; de Belder, M.; Singh, R.; Teggert, A.; Wood, E.; Brennan, G.; et al. Utility of biomarkers in the differential diagnosis of heart failure in older people: Findings from the heart failure in care homes (HFinCH) diagnostic accuracy study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53560.

- Oprea, V.D.; Marinescu, M.; Rișcă Popazu, C.; Sârbu, F.; Onose, G.; Romila, A. Cardiovascular Comorbidities in Relation to the Functional Status and Vitamin D Levels in Elderly Patients with Dementia. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2994.

- Plichart, M.; Orvoen, G.; Jourdain, P.; Quinquis, L.; Coste, J.; Escande, M.; Friocourt, P.; Paillaud, E.; Chedhomme, F.X.; Labouree, F.; et al. Brain natriuretic peptide usefulness in very elderly dyspnoeic patients: The BED study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 540–548.

- Emdin, M.; Aimo, A.; Passino, C.; Vergaro, G. Breathing Not Properly in the oldest old. Is brain natriuretic peptide a poor test for the diagnosis of heart failure in the elderly? Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 549–551.

- Pfisterer, M. BNP-guided vs symptom- guided heart failure therapy the trial of intensified vs standard medical therapy in elderly patients with congestive heart failure (TIME-CHF) randomized trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2009, 301, 383–392.

- Cherubini, A.; Oristrell, J.; Pla, X.; Ruggiero, C.; Ferretti, R.; Diestre, G.; Clarfield, A.M.; Crome, P.; Hertogh, C.; Lesauskaite, V.; et al. The persistent exclusion of older patients from ongoing clinical trials regarding heart failure. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011, 171, 550–556.

- Clerico, A.; Emdin, M. Diagnostic accuracy and prognostic relevance of the measurement of cardiac natriuretic peptides: A review. Clin. Chem. 2004, 50, 33–50.

- Blondé-Cynober, F.; Morineau, G.; Estrugo, B.; Fillie, E.; Aussel, C.; Vincent, J.P. Diagnostic and prognostic value of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) concentrations in very elderly heart disease patients: Specific geriatric cut-off and impacts of age, gender, renal dysfunction, and nutritional status. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 52, 106–110.

- Teixeira, A.; Arrigo, M.; Vergaro, G.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Mebazaa, A. Clinical benefits of natriuretic peptides and galectin-3 are maintained in old dysonoeic patients. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 68, 33–38.

- Maisel, A.S.; Clopton, P.; Krishnaswamy, P.; Nowak, R.M.; McCord, J.; Hollander, J.E.; Duc, P.; Omland, T.; Storrow, A.B.; Abraham, W.T.; et al. BNP Multinational Study Investigators. Impact of age, race, and sex on the ability of B-type natriuretic peptide to aid in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure: Results from the Breathing Not Properly (BNP) multinational study. Am. Heart J. 2004, 147, 1078–1084.

- Metra, M.; Cotter, G.; El-Khorazaty, J.; Davison, B.A.; Milo, O.; Carubelli, V.; Bourge, R.C.; Cleland, J.G.; Jondeau, G.; Krum, H.; et al. Acute heart failure in the elderly: Differences in clinical characteristics, outcomes, and prognostic factors in the VERITAS Study. J. Card. Fail. 2015, 21, 179–188.

More

Information

Subjects:

Geriatrics & Gerontology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Entry Collection:

Hypertension and Cardiovascular Diseases

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

16 May 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No