Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Muslum Ilgu | -- | 1052 | 2023-05-08 13:56:13 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1052 | 2023-05-10 08:06:01 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Kara, N.; Ayoub, N.; Ilgu, H.; Fotiadis, D.; Ilgu, M. Membrane Proteins in Diseases and Potential as Biomarkers. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43982 (accessed on 02 March 2026).

Kara N, Ayoub N, Ilgu H, Fotiadis D, Ilgu M. Membrane Proteins in Diseases and Potential as Biomarkers. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43982. Accessed March 02, 2026.

Kara, Nilufer, Nooraldeen Ayoub, Huseyin Ilgu, Dimitrios Fotiadis, Muslum Ilgu. "Membrane Proteins in Diseases and Potential as Biomarkers" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43982 (accessed March 02, 2026).

Kara, N., Ayoub, N., Ilgu, H., Fotiadis, D., & Ilgu, M. (2023, May 08). Membrane Proteins in Diseases and Potential as Biomarkers. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43982

Kara, Nilufer, et al. "Membrane Proteins in Diseases and Potential as Biomarkers." Encyclopedia. Web. 08 May, 2023.

Copy Citation

Many biological processes (physiological or pathological) are relevant to membrane proteins (MPs), which account for almost 30% of the total of human proteins. As such, MPs can serve as predictive molecular biomarkers for disease diagnosis and prognosis.

aptamers

aptasensor

biosensor

1. Introduction

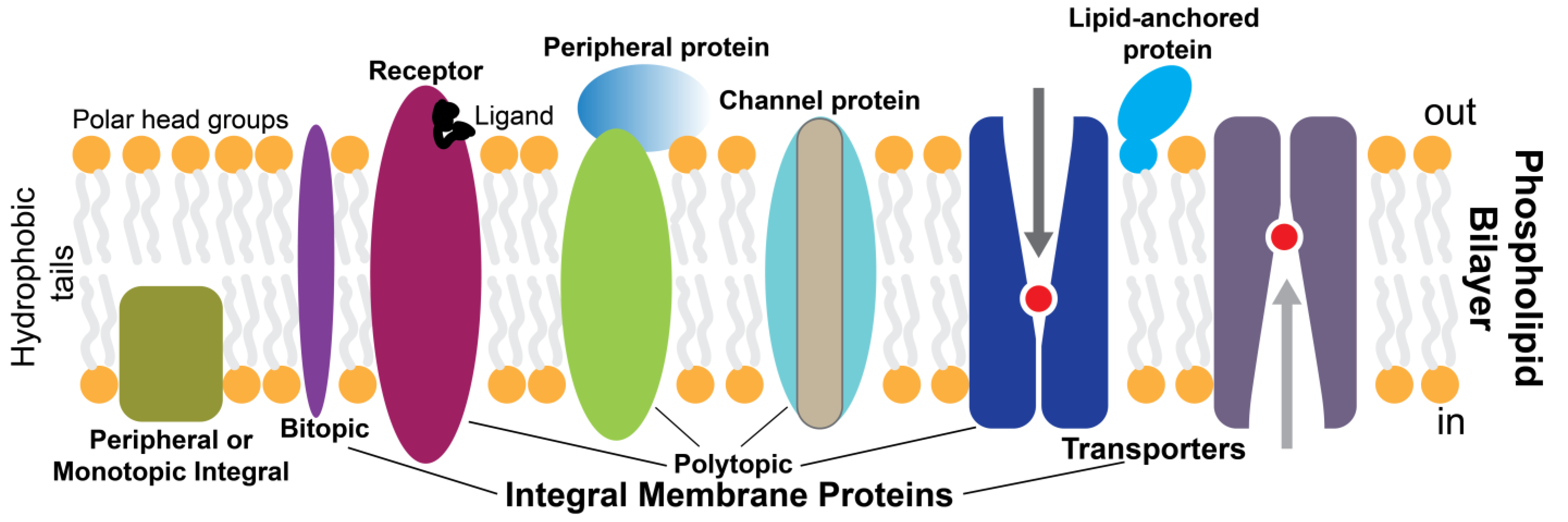

The biological membranes are essential for cellular life. They form and organize cells’ defining boundaries, e.g., by separating the interior from the outside environment. Most cell membranes consist of about half lipid and half protein by weight. Membrane proteins (MPs) are proteins embedded or attached to biological membranes and are thus classified as peripheral or integral. Integral MPs fully span the lipid bilayer, while peripheral MPs partially associate with the lipid bilayer or with integral MPs (Figure 1). MPs are broadly amphipathic, having hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions, and they distribute asymmetrically through the membrane, with some being modified with carbohydrate moieties [1]. The hydrophobic nature of the lipid bilayer core limits the possible transmembrane protein structures to α-helix and β-barrel structures. MPs perform most of the specific functions of membranes. For example, receptors and transporters play critical roles in transmitting information and molecules into a cell or organelle. Cell receptors sense external cues and integrate them to respond through coordinated signal transduction pathways. Considering their important physiological roles, MPs are crucial in medicine, pharmacology, and drug discovery representing the vast majority of therapeutic drug targets [2]. These clinical drug targets include channels, transporters, and in particular, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [3].

Figure 1. Simplistic overview of membrane proteins in a lipid bilayer.

Functional characteristics of organelles and cells are determined by the protein compositions at different physiological states [4]. Changes in genetic composition or level of MPs are associated with various diseases, for which rapid and early identification become possible with the development of specific recognition elements for these MPs [5]. In the last three decades, nucleic acid aptamers have been selected and optimized for numerous MPs, and they have become antibody alternatives to be integrated into diagnostic tools. According to the Biomarkers Definitions Working Group convened by the National Institute of Health (NIH), a biomarker (e.g., DNA, RNA, proteins, small metabolites, etc.) is a measurable indicator for normal biological or pathogenic processes and responses to pharmacological intervention [6]. Therefore, biomarkers have important applications in modern healthcare systems where they are used in the diagnosis of diseases and their extent, as well as their prognosis [7][8]. Other related biomarker applications can be seen in routine health checkups and monitoring of patient health status.

2. Membrane Proteins: Role in Diseases and Potential as Biomarkers

Approximately 30% of the total human proteome is composed of MPs [4][9]. Having important physiological roles, MPs are critical in the development and progress of various pathological conditions. For example, G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are a well-characterized class of membrane receptors encoded by more than 800 human genes [10]. They are dynamic signaling receptors that play roles in major signaling pathways, such as those related to the actions of drugs, toxins, hormones, and neurotransmitters, sensing light and odors, and regulating water reabsorption and blood calcium levels [11][12]. Acquired and inherited genetic mutations result in GPCR dysfunctions and, thus, disorders like retinitis pigmentosa, hypo- and hyperthyroidism, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, fertility disorders, and different carcinomas [13]. Channelopathies, such as long QT syndrome and cystic fibrosis, are another group of disease conditions that can arise from defects in the class of transmembrane proteins comprising ligand- and voltage-activated ion channels [14][15]. These channels are known to regulate ion and water balance, membrane potentials, and signal transduction.

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) involve a class of membrane receptors encoded by 60 human genes and participate in important functions, such as regulation of cell survival, metabolism, proliferation, and differentiation [16]. Dysfunctional RTKs result in developmental problems leading to diseases, including diabetes, atherosclerosis, and cancer. For example, RTKs are well-studied and targeted therapeutics for cancer [17] and diabetes [18].

Transporter proteins are another important class of MPs encoded by 10% of human genes [19][20]. They include families of active, ATP-dependent transporters known as ATPases that are responsible for cell survival by achieving different ionic equilibria of sodium, potassium, calcium, and H+ ions (i.e., P-type ATPases) [21][22]. Malfunction in these transporters leads to various diseases ranging from migraines, heritable deafness, and balance disorder to renal diseases, copper-related disorders, and cancers [23][24]. Transporters are emerging as attractive drug targets [25]. Solute carrier (SLC) proteins are a rich and diverse group of transporters that facilitate the transport of various molecules, including glucose, amino acids, fatty acids, urea, bile salts, large organic ions, nucleosides, and neurotransmitters [20]. Defects in SLC transporters, therefore, have implications in neurodegenerative diseases [26] and many metabolic disorders [20].

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins include a group of transporters with various unique functions like the transport of peptides, phospholipids, bile materials (e.g., salts, cholesterol, etc.), and surfactants, and the presentation of antigens [4][27]. Multidrug resistance (MDR)-ABC proteins are involved in the metabolism and transport of many foreign materials, including endo- and xenobiotics, anticancer drugs, and partially detoxified drug metabolites. Alterations in the structure and expression of MDR-ABC transporters have implications for cancer drug resistance and can also alter the toxicity of many drugs [20].

Finally, the epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) is a structural MP that plays various roles in physiological processes and diseases such as cancer [28][29] and is known to be overexpressed in cancerous cells [30][31]. In cancers, including pancreatic, breast, colorectal, and prostate, the presence of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in the peripheral blood was described [32]. These CTCs detach from primary tumors and enter the circulatory system, ultimately causing malignancies in distant secondary organs.

A critical factor that unites all the above-mentioned MPs is the outcome of their abnormal manifestation (i.e., mutated, overexpressed, etc.), upon which they can potentially serve as disease biomarkers detectable by diagnostic means [4]. In general, biomarkers must fulfill the following defining guidelines: (i) are relevant to the phenotype under investigation, (ii) can be assayed reliably, (iii) readily available (stable) for detection, and (iv) recognizable by current clinical methods [4]. Infectious diseases caused by pathogenic agents (e.g., viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi) can pose serious public health issues, so they get significant attention for clinical diagnosis using similar biomarker-based approaches [33][34][35]. For example, hemagglutinin (HA) is a well-known surface glycoprotein of the influenza virus [36] that attracted the development of targeted diagnostic procedures for HA-driven infections [37]. More recently, angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE2) and the SARS-CoV-2 spike and nucleocapsid proteins have all become important diagnostic and therapeutic targets in the fight against COVID-19 [38][39].

References

- Yeagle, P.L. Chapter 10—Membrane Proteins. In The Membranes of Cells; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; ISBN 9780128004869.

- Dua, P.; Kim, S.; Lee, D.-K. Nucleic Acid Aptamers Targeting Cell-Surface Proteins. Methods 2011, 54, 215–225.

- Overington, J.P.; Al-Lazikani, B.; Hopkins, A.L. How Many Drug Targets Are There? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 993–996.

- Várady, G.; Cserepes, J.; Németh, A.; Szabó, E.; Sarkadi, B. Cell Surface Membrane Proteins as Personalized Biomarkers: Where We Stand and Where We Are Headed. Biomark. Med. 2013, 7, 803–819.

- Cibiel, A.; Dupont, D.M.; Ducongé, F. Methods to Identify Aptamers against Cell Surface Biomarkers. Pharmaceuticals 2011, 4, 1216–1235.

- Atkinson, A.J.; Colburn, W.A.; DeGruttola, V.G.; DeMets, D.L.; Downing, G.J.; Hoth, D.F.; Oates, J.A.; Peck, C.C.; Schooley, R.T.; Spilker, B.A.; et al. Biomarkers and Surrogate Endpoints: Preferred Definitions and Conceptual Framework. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 69, 89–95.

- Chakrapani, A.T. Biomarkers of Diseases: Their Role in Emergency Medicine. In Neurodegenerative Diseases—Molecular Mechanisms and Current Therapeutic Approaches; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021.

- Conde, I.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Paredes, J. Breast Cancer Stem Cell Membrane Biomarkers: Therapy Targeting and Clinical Implications. Cells 2022, 11, 934.

- Almén, M.S.; Nordström, K.J.V.; Fredriksson, R.; Schiöth, H.B. Mapping the Human Membrane Proteome: A Majority of the Human Membrane Proteins Can Be Classified According to Function and Evolutionary Origin. BMC Biol. 2009, 7, 50.

- Palczewski, K. Oligomeric Forms of G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs). Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010, 35, 595–600.

- Pei, Y.; Rogan, S.C.; Yan, F.; Roth, B.L. Engineered GPCRs as Tools to Modulate Signal Transduction. Physiology 2008, 23, 313–321.

- Ahmad, R.; Dalziel, J.E. G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Taste Physiology and Pharmacology. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 587664.

- Schöneberg, T.; Schulz, A.; Biebermann, H.; Hermsdorf, T.; Römpler, H.; Sangkuhl, K. Mutant G-Protein-Coupled Receptors as a Cause of Human Diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 104, 173–206.

- Raines, R.; McKnight, I.; White, H.; Legg, K.; Lee, C.; Li, W.; Lee, P.H.U.; Shim, J.W. Drug-Targeted Genomes: Mutability of Ion Channels and GPCRs. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 594.

- Inanobe, A.; Kurachi, Y. Membrane Channels as Integrators of G-Protein-Mediated Signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2014, 1838, 521–531.

- Ségaliny, A.I.; Tellez-Gabriel, M.; Heymann, M.F.; Heymann, D. Receptor Tyrosine Kinases: Characterisation, Mechanism of Action and Therapeutic Interests for Bone Cancers. J. Bone Oncol. 2015, 4, 1–12.

- Mongre, R.K.; Mishra, C.B.; Shukla, A.K.; Prakash, A.; Jung, S.; Ashraf-Uz-zaman, M.; Lee, M.S. Emerging Importance of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors against Cancer: Quo Vadis to Cure? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11659.

- Oakie, A.; Wang, R. Beta-Cell Receptor Tyrosine Kinases in Controlling Insulin Secretion and Exocytotic Machinery: C-Kit and Insulin Receptor. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 3813–3821.

- Scalise, M.; Console, L.; Galluccio, M.; Pochini, L.; Indiveri, C. Chemical Targeting of Membrane Transporters: Insights into Structure/Function Relationships. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 2069–2080.

- Hediger, M.A.; Clémençon, B.; Burrier, R.E.; Bruford, E.A. The ABCs of Membrane Transporters in Health and Disease (SLC Series): Introduction. Mol. Asp. Med. 2013, 34, 95–107.

- Toei, M.; Saum, R.; Forgac, M. Regulation and Isoform Function of the V-ATPases. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 4715–4723.

- Collins, M.P.; Forgac, M. Regulation and Function of V-ATPases in Physiology and Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183341.

- Bechmann, M.B.; Rotoli, D.; Morales, M.; del Carmen Maeso, M.; del Pino García, M.; Ávila, J.; Mobasheri, A.; Martín-Vasallo, P. Na, K-ATPase Isozymes in Colorectal Cancer and Liver Metastases. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 9.

- Li, Z.; Langhans, S.A. Transcriptional Regulators of Na, K-ATPase Subunits. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 3, 66.

- Lin, L.; Yee, S.W.; Kim, R.B.; Giacomini, K.M. SLC Transporters as Therapeutic Targets: Emerging Opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 543–560.

- Aykaç, A.; Şehirli, A.Ö. The Role of the SLC Transporters Protein in the Neurodegenerative Disorders. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2020, 18, 174–187.

- Hou, R.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.J. Predicting ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters Using the Random Forest Method. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 156.

- Huang, L.; Yang, Y.; Yang, F.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Z.; Lei, Z.; Guo, J. Functions of EpCAM in Physiological Processes and Diseases (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 1771–1785.

- Tjensvoll, K.; Nordgård, O.; Smaaland, R. Circulating Tumor Cells in Pancreatic Cancer Patients: Methods of Detection and Clinical Implications. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 134, 1–8.

- Spizzo, G.; Went, P.; Dirnhofer, S.; Obrist, P.; Simon, R.; Spichtin, H.; Maurer, R.; Metzger, U.; von Castelberg, B.; Bart, R.; et al. High Ep-CAM Expression Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Node-Positive Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2004, 86, 207–213.

- Went, P.T.; Lugli, A.; Meier, S.; Bundi, M.; Mirlacher, M.; Sauter, G.; Dirnhofer, S. Frequent EpCam Protein Expression in Human Carcinomas. Hum. Pathol. 2004, 35, 122–128.

- Mikolajczyk, S.D.; Millar, L.S.; Tsinberg, P.; Coutts, S.M.; Zomorrodi, M.; Pham, T.; Bischoff, F.Z.; Pircher, T.J. Detection of EpCAM-Negative and Cytokeratin-Negative Circulating Tumor Cells in Peripheral Blood. J. Oncol. 2011, 2011, 1–10.

- Hwang, H.; Hwang, B.Y.; Bueno, J. Biomarkers in Infectious Diseases. Dis. Markers 2018, 2018.

- Ilgu, M.; Fazlioglu, R.; Ozturk, M.; Ozsurekci, Y.; Nilsen-Hamilton, M. Aptamers for Diagnostics with Applications for Infectious Diseases. In Recent Advances in Analytical Chemistry; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–32.

- Liu, L.S.; Wang, F.; Ge, Y.; Lo, P.K. Recent Developments in Aptasensors for Diagnostic Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 9329–9358.

- Wandtke, T.; Woźniak, J.; Kopiński, P. Aptamers in Diagnostics and Treatment of Viral Infections. Viruses 2015, 7, 751–780.

- Ramos, K.C.; Nishiyama, K.; Maeki, M.; Ishida, A.; Tani, H.; Kasama, T.; Baba, Y.; Tokeshi, M. Rapid, Sensitive, and Selective Detection of H5 Hemagglutinin from Avian Influenza Virus Using an Immunowall Device. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 16683–16688.

- Zanganeh, S.; Goodarzi, N.; Doroudian, M.; Movahed, E. Potential COVID-19 Therapeutic Approaches Targeting Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2; An Updated Review. Rev. Med. Virol. 2022, 32, e2321.

- Liu, W.; Liu, L.; Kou, G.; Zheng, Y.; Ding, Y.; Ni, W.; Wang, Q.; Tan, L.; Wu, W.; Tang, S.; et al. Evaluation of Nucleocapsid and Spike Protein-Based Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays for Detecting Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e00461-20.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.7K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

11 May 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No