| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sivakumar Vijayaraghavalu | -- | 3091 | 2023-04-28 09:53:52 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | -1 word(s) | 3090 | 2023-04-28 10:14:28 | | |

Video Upload Options

Stem cells’ self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation are regulated by a complex network consisting of signaling factors, chromatin regulators, transcription factors, and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). Diverse role of ncRNAs in stem cell development and maintenance of bone homeostasis have been discovered recently. The ncRNAs, such as long non-coding RNAs, micro RNAs, circular RNAs, small interfering RNA, Piwi-interacting RNAs, etc., are not translated into proteins but act as essential epigenetic regulators in stem cells’ self-renewal and differentiation. Different signaling pathways are monitored efficiently by the differential expression of ncRNAs, which function as regulatory elements in determining the fate of stem cells. In addition, several species of ncRNAs could serve as potential molecular biomarkers in early diagnosis of bone diseases, including osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, and bone cancers, ultimately leading to the development of new therapeutic strategies.

1. ncRNAs and Bone Diseases

1.1. lncRNAs and SNPs in Bone Disease

1.2. circRNAs and Bone Diseases

1.3. piRNAs and Bone Disease

1.4. siRNA and Bone Disease

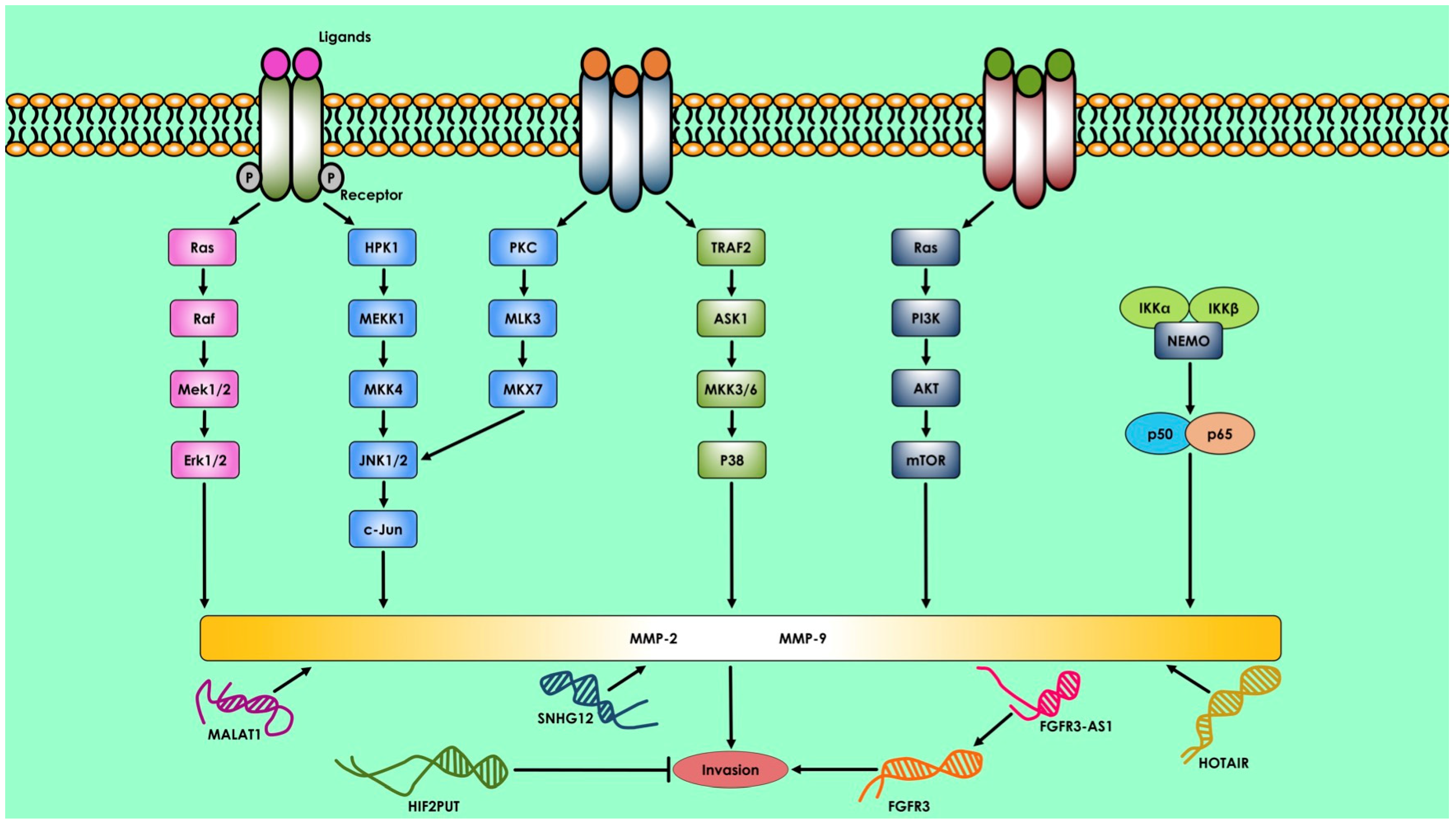

1.5. ncRNAs and Bone Cancer

2. Therapeutics Approach of ncRNAs in Bone Disease

2.1. lncRNAs in Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis Treatment

2.2. miRNAs in Bone Diseases and Fractures

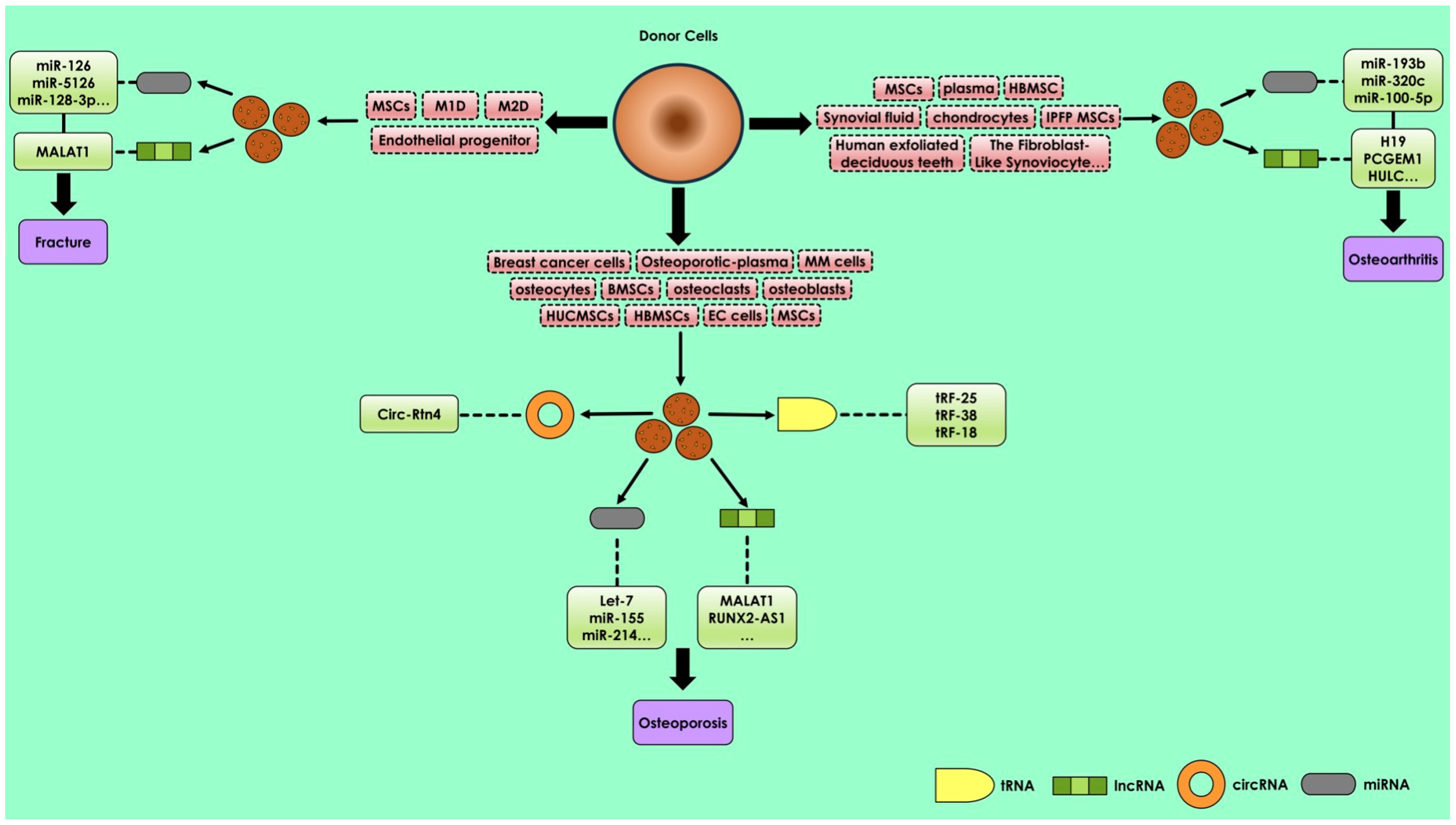

2.3. Treatment of Osteoporosis by Exosomal miRNAs

2.4. Treatment of Osteoarthritis by Exsomal miRNAs

References

- Zeng, Q.; Wu, K.-H.; Liu, K.; Hu, Y.; Chen, X.-D.; Zhang, L.; Shen, H.; Tian, Q.; Zhao, L.-J.; Deng, H.-W.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of LncRNA Polymorphisms with Bone Mineral Density. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2018, 82, 244–253.

- Styrkarsdottir, U.; Halldorsson, B.V.; Gretarsdottir, S.; Gudbjartsson, D.F.; Walters, G.B.; Ingvarsson, T.; Jonsdottir, T.; Saemundsdottir, J.; Center, J.R.; Nguyen, T.V.; et al. Multiple Genetic Loci for Bone Mineral Density and Fractures. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2355–2365.

- Chen, X.-F.; Zhu, D.-L.; Yang, M.; Hu, W.-X.; Duan, Y.-Y.; Lu, B.-J.; Rong, Y.; Dong, S.-S.; Hao, R.-H.; Chen, J.-B.; et al. An Osteoporosis Risk SNP at 1p36.12 Acts as an Allele-Specific Enhancer to Modulate LINC00339 Expression via Long-Range Loop Formation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 102, 776–793.

- Strzelecka-Kiliszek, A.; Mebarek, S.; Roszkowska, M.; Buchet, R.; Magne, D.; Pikula, S. Functions of Rho Family of Small GTPases and Rho-Associated Coiled-Coil Kinases in Bone Cells during Differentiation and Mineralization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 1009–1023.

- Prats, A.-C.; David, F.; Diallo, L.H.; Roussel, E.; Tatin, F.; Garmy-Susini, B.; Lacazette, E. Circular RNA, the Key for Translation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8591.

- Ma, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, L. Biogenesis and Functions of Circular RNAs and Their Role in Diseases of the Female Reproductive System. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2020, 18, 104.

- Li, Z.; Li, X.; Xu, D.; Chen, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Chan, M.T.V.; Wu, W.K.K. An Update on the Roles of Circular RNAs in Osteosarcoma. Cell Prolif. 2021, 54, e12936.

- Wang, X.-B.; Li, P.-B.; Guo, S.-F.; Yang, Q.-S.; Chen, Z.-X.; Wang, D.; Shi, S.-B. CircRNA_0006393 Promotes Osteogenesis in Glucocorticoid-induced Osteoporosis by Sponging MiR-145-5p and Upregulating FOXO1. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 2851–2858.

- Zhou, Z.-B.; Huang, G.-X.; Fu, Q.; Han, B.; Lu, J.-J.; Chen, A.-M.; Zhu, L. CircRNA.33186 Contributes to the Pathogenesis of Osteoarthritis by Sponging MiR-127-5p. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 531–541.

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, W.; Hu, H.; Wang, X.; Hao, D. LncRNA/CircRNA-MiRNA-MRNA CeRNA Network in Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 3160–3174.

- Yu, L.; Liu, Y. CircRNA_0016624 Could Sponge MiR-98 to Regulate BMP2 Expression in Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 516, 546–550.

- Liu, S.; Wang, C.; Bai, J.; Li, X.; Yuan, J.; Shi, Z.; Mao, N. Involvement of CircRNA_0007059 in the Regulation of Postmenopausal Osteoporosis by Promoting the MicroRNA-378/BMP-2 Axis. Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 45, 447–455.

- Zhang, M.; Jia, L.; Zheng, Y. CircRNA Expression Profiles in Human Bone Marrow Stem Cells Undergoing Osteoblast Differentiation. Stem. Cell Rev. Rep. 2019, 15, 126–138.

- Qiao, L.; Li, C.-G.; Liu, D. CircRNA_0048211 Protects Postmenopausal Osteoporosis through Targeting MiRNA-93-5p to Regulate BMP2. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 3459–3466.

- Luo, Y.; Qiu, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Y. Circular RNAs in Osteoporosis: Expression, Functions and Roles. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 231.

- Dou, C.; Cao, Z.; Yang, B.; Ding, N.; Hou, T.; Luo, F.; Kang, F.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Jiang, H.; et al. Changing Expression Profiles of LncRNAs, MRNAs, CircRNAs and MiRNAs during Osteoclastogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21499.

- Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Huang, P.; Hu, F.; Jiang, M.; Xu, X.; Li, B.; Deng, L.; Ye, T.; Guo, L. CircHmbox1 Targeting MiRNA-1247-5p Is Involved in the Regulation of Bone Metabolism by TNF-α in Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 594785.

- Li, X.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.-L. The Biogenesis, Functions, and Challenges of Circular RNAs. Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 428–442.

- Peng, W.; Zhu, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Rong, Q.; Chen, S. Hsa_circRNA_33287 Promotes the Osteogenic Differentiation of Maxillary Sinus Membrane Stem Cells via MiR-214-3p/Runx3. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1709–1717.

- Chen, G.; Wang, S.; Long, C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Tang, W.; He, X.; Bao, Z.; Tan, B.; Lu, W.W.; et al. PiRNA-63049 Inhibits Bone Formation through Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 4409–4425.

- Aravin, A.A.; Naumova, N.M.; Tulin, A.V.; Vagin, V.V.; Rozovsky, Y.M.; Gvozdev, V.A. Double-Stranded RNA-Mediated Silencing of Genomic Tandem Repeats and Transposable Elements in the D. Melanogaster Germline. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, 1017–1027.

- Yamashiro, H.; Siomi, M.C. PIWI-Interacting RNA in Drosophila: Biogenesis, Transposon Regulation, and Beyond. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4404–4421.

- Yan, H.; Wu, Q.-L.; Sun, C.-Y.; Ai, L.-S.; Deng, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Chu, Z.-B.; Tang, B.; Wang, K.; et al. PiRNA-823 Contributes to Tumorigenesis by Regulating de Novo DNA Methylation and Angiogenesis in Multiple Myeloma. Leukemia 2015, 29, 196–206.

- Wu, W.; Lu, B.-F.; Jiang, R.-Q.; Chen, S. The Function and Regulation Mechanism of PiRNAs in Human Cancers. Histol. Histopathol. 2021, 36, 807–816.

- Liu, Y.; Dou, M.; Song, X.; Dong, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Tao, J.; Li, W.; Yin, X.; Xu, W. The Emerging Role of the PiRNA/Piwi Complex in Cancer. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 123.

- Della Bella, E.; Menzel, U.; Basoli, V.; Tourbier, C.; Alini, M.; Stoddart, M.J. Differential Regulation of CircRNA, MiRNA, and PiRNA during Early Osteogenic and Chondrogenic Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Cells 2020, 9, 398.

- Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Ma, L.; Dang, X.; Du, G. PiRNA-36741 Regulates BMP2-Mediated Osteoblast Differentiation via METTL3 Controlled M6A Modification. Aging 2021, 13, 23361–23375.

- Fire, A.; Xu, S.; Montgomery, M.K.; Kostas, S.A.; Driver, S.E.; Mello, C.C. Potent and Specific Genetic Interference by Double-Stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Nature 1998, 391, 806–811.

- Ghadakzadeh, S.; Mekhail, M.; Aoude, A.; Hamdy, R.; Tabrizian, M. Small Players Ruling the Hard Game: SiRNA in Bone Regeneration. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2016, 31, 475–487.

- McBride, J.L.; Boudreau, R.L.; Harper, S.Q.; Staber, P.D.; Monteys, A.M.; Martins, I.; Gilmore, B.L.; Burstein, H.; Peluso, R.W.; Polisky, B.; et al. Artificial MiRNAs Mitigate ShRNA-Mediated Toxicity in the Brain: Implications for the Therapeutic Development of RNAi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 5868–5873.

- Liu, X. Bone Site-Specific Delivery of SiRNA. J. Biomed. Res. 2016, 30, 264–271.

- Kanasty, R.; Dorkin, J.R.; Vegas, A.; Anderson, D. Delivery Materials for SiRNA Therapeutics. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 967–977.

- Gavrilov, K.; Saltzman, W.M. Therapeutic SiRNA: Principles, Challenges, and Strategies. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2012, 85, 187–200.

- Naito, Y.; Ui-Tei, K. Designing Functional SiRNA with Reduced Off-Target Effects. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 942, 57–68.

- Chalk, A.M.; Wahlestedt, C.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L. Improved and Automated Prediction of Effective SiRNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 319, 264–274.

- Chen, X.; Mangala, L.S.; Rodriguez-Aguayo, C.; Kong, X.; Lopez-Berestein, G.; Sood, A.K. RNA Interference–Based Therapy and Its Delivery Systems. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018, 37, 107–124.

- Isakoff, M.S.; Bielack, S.S.; Meltzer, P.; Gorlick, R. Osteosarcoma: Current Treatment and a Collaborative Pathway to Success. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3029–3035.

- Lin, Y.-H.; Jewell, B.E.; Gingold, J.; Lu, L.; Zhao, R.; Wang, L.L.; Lee, D.-F. Osteosarcoma: Molecular Pathogenesis and IPSC Modeling. Trends. Mol. Med. 2017, 23, 737–755.

- Su, X.; Malouf, G.G.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yao, H.; Valero, V.; Weinstein, J.N.; Spano, J.-P.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Khayat, D.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Human Breast Cancer Clinical Subtypes. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 9864–9876.

- Martens-Uzunova, E.S.; Böttcher, R.; Croce, C.M.; Jenster, G.; Visakorpi, T.; Calin, G.A. Long Noncoding RNA in Prostate, Bladder, and Kidney Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2014, 65, 1140–1151.

- Smolle, M.; Uranitsch, S.; Gerger, A.; Pichler, M.; Haybaeck, J. Current Status of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Human Cancer with Specific Focus on Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 13993–14013.

- Gibb, E.A.; Brown, C.J.; Lam, W.L. The Functional Role of Long Non-Coding RNA in Human Carcinomas. Mol. Cancer 2011, 10, 38.

- Ohtsuka, M.; Ling, H.; Ivan, C.; Pichler, M.; Matsushita, D.; Goblirsch, M.; Stiegelbauer, V.; Shigeyasu, K.; Zhang, X.; Chen, M.; et al. H19 Noncoding RNA, an Independent Prognostic Factor, Regulates Essential Rb-E2F and CDK8-β-Catenin Signaling in Colorectal Cancer. EBioMedicine 2016, 13, 113–124.

- Kanlikilicer, P.; Rashed, M.H.; Bayraktar, R.; Mitra, R.; Ivan, C.; Aslan, B.; Zhang, X.; Filant, J.; Silva, A.M.; Rodriguez-Aguayo, C.; et al. Ubiquitous Release of Exosomal Tumor Suppressor MiR-6126 from Ovarian Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 7194–7207.

- Cerk, S.; Schwarzenbacher, D.; Adiprasito, J.B.; Stotz, M.; Hutterer, G.C.; Gerger, A.; Ling, H.; Calin, G.A.; Pichler, M. Current Status of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Human Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1485.

- Smolle, M.A.; Calin, H.N.; Pichler, M.; Calin, G.A. Noncoding RNAs and Immune Checkpoints-Clinical Implications as Cancer Therapeutics. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 1952–1966.

- Li, J.-P.; Liu, L.-H.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, X.-W.; Ouyang, Y.-R.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Zhong, H.; Li, H.; Xiao, T. Microarray Expression Profile of Long Noncoding RNAs in Human Osteosarcoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 433, 200–206.

- Dong, Y.; Liang, G.; Yuan, B.; Yang, C.; Gao, R.; Zhou, X. MALAT1 Promotes the Proliferation and Metastasis of Osteosarcoma Cells by Activating the PI3K/Akt Pathway. Tumour. Biol. 2015, 36, 1477–1486.

- Qian, M.; Yang, X.; Li, Z.; Jiang, C.; Song, D.; Yan, W.; Liu, T.; Wu, Z.; Kong, J.; Wei, H.; et al. P50-Associated COX-2 Extragenic RNA (PACER) Overexpression Promotes Proliferation and Metastasis of Osteosarcoma Cells by Activating COX-2 Gene. Tumour. Biol. 2016, 37, 3879–3886.

- Tian, Z.-Z.; Guo, X.-J.; Zhao, Y.-M.; Fang, Y. Decreased Expression of Long Non-Coding RNA MEG3 Acts as a Potential Predictor Biomarker in Progression and Poor Prognosis of Osteosarcoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 15138–15142.

- Lu, K.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Sun, M.; Zhang, M.; Wu, W.; Xie, W.; Hou, Y. Long Non-Coding RNA MEG3 Inhibits NSCLC Cells Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis by Affecting P53 Expression. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 461.

- Yin, D.-D.; Liu, Z.-J.; Zhang, E.; Kong, R.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Guo, R.-H. Decreased Expression of Long Noncoding RNA MEG3 Affects Cell Proliferation and Predicts a Poor Prognosis in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Tumour. Biol. 2015, 36, 4851–4859.

- Sun, L.; Yang, C.; Xu, J.; Feng, Y.; Wang, L.; Cui, T. Long Noncoding RNA EWSAT1 Promotes Osteosarcoma Cell Growth and Metastasis Through Suppression of MEG3 Expression. DNA Cell Biol. 2016, 35, 812–818.

- Yu, X.; Zheng, H.; Chan, M.T.V.; Wu, W.K.K. HULC: An Oncogenic Long Non-Coding RNA in Human Cancer. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 410–417.

- Hämmerle, M.; Gutschner, T.; Uckelmann, H.; Ozgur, S.; Fiskin, E.; Gross, M.; Skawran, B.; Geffers, R.; Longerich, T.; Breuhahn, K.; et al. Posttranscriptional Destabilization of the Liver-Specific Long Noncoding RNA HULC by the IGF2 MRNA-Binding Protein 1 (IGF2BP1). Hepatology 2013, 58, 1703–1712.

- Cui, M.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Song, T.; Cai, X.; Sun, B.; Ye, L.; Zhang, X. Long Noncoding RNA HULC Modulates Abnormal Lipid Metabolism in Hepatoma Cells through an MiR-9–Mediated RXRA Signaling Pathway. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 846–857.

- Li, S.-P.; Xu, H.-X.; Yu, Y.; He, J.-D.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.-J.; Wang, C.-Y.; Zhang, H.-M.; Zhang, R.-X.; Zhang, J.-J.; et al. LncRNA HULC Enhances Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition to Promote Tumorigenesis and Metastasis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma via the MiR-200a-3p/ZEB1 Signaling Pathway. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 42431–42446.

- Yang, X.-J.; Huang, C.-Q.; Peng, C.-W.; Hou, J.-X.; Liu, J.-Y. Long Noncoding RNA HULC Promotes Colorectal Carcinoma Progression through Epigenetically Repressing NKD2 Expression. Gene 2016, 592, 172–178.

- Lu, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Liu, F.; Cui, M.; Li, W.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Ye, L.; Zhang, X. Long Non-Coding RNA HULC Promotes Tumor Angiogenesis in Liver Cancer by up-Regulating Sphingosine Kinase 1 (SPHK1). Oncotarget 2015, 7, 241–254.

- Sun, X.-H.; Yang, L.-B.; Geng, X.-L.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Z.-C. Increased Expression of LncRNA HULC Indicates a Poor Prognosis and Promotes Cell Metastasis in Osteosarcoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 2994–3000.

- Qiu, J.; Lin, Y.; Ye, L.; Ding, J.; Feng, W.; Jin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Hua, K. Overexpression of Long Non-Coding RNA HOTAIR Predicts Poor Patient Prognosis and Promotes Tumor Metastasis in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 134, 121–128.

- Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; De, W. The Long Non-Coding RNA HOTAIR Indicates a Poor Prognosis and Promotes Metastasis in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 464.

- Xue, X.; Yang, Y.A.; Zhang, A.; Fong, K.-W.; Kim, J.; Song, B.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.C.; Yu, J. LncRNA HOTAIR Enhances ER Signaling and Confers Tamoxifen Resistance in Breast Cancer. Oncogene 2016, 35, 2746–2755.

- Wu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, S. Role of the Long Non-Coding RNA HOTAIR in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 1233–1239.

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, L.; Piao, H.; Ma, L. Long Non-Coding RNA HOTAIR in Carcinogenesis and Metastasis. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2014, 46, 1–5.

- Tsai, M.-C.; Manor, O.; Wan, Y.; Mosammaparast, N.; Wang, J.K.; Lan, F.; Shi, Y.; Segal, E.; Chang, H.Y. Long Noncoding RNA as Modular Scaffold of Histone Modification Complexes. Science 2010, 329, 689–693.

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, F.; Fei, Z.; Zhao, J.; Liang, Y.; Pan, W.; Liu, X.; Zheng, D. Genetic Variants of LncRNA HOTAIR Contribute to the Risk of Osteosarcoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 19928–19934.

- Li, F.; Cao, L.; Hang, D.; Wang, F.; Wang, Q. Long Non-Coding RNA HOTTIP Is up-Regulated and Associated with Poor Prognosis in Patients with Osteosarcoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 11414–11420.

- Cheng, Y.; Jutooru, I.; Chadalapaka, G.; Corton, J.C.; Safe, S. The Long Non-Coding RNA HOTTIP Enhances Pancreatic Cancer Cell Proliferation, Survival and Migration. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 10840–10852.

- Chen, X.; Han, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Mo, K.; Chen, S. Upregulation of Long Noncoding RNA HOTTIP Promotes Metastasis of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma via Induction of EMT. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 84480–84485.

- Lian, Y.; Cai, Z.; Gong, H.; Xue, S.; Wu, D.; Wang, K. HOTTIP: A Critical Oncogenic Long Non-Coding RNA in Human Cancers. Mol. Biosyst. 2016, 12, 3247–3253.

- Chen, R.; Wang, G.; Zheng, Y.; Hua, Y.; Cai, Z. Long Non-Coding RNAs in Osteosarcoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 20462–20475.

- Valavanis, C.; Stanc, G.; Valavanis, C.; Stanc, G. Long Noncoding RNAs in Osteosarcoma: Mechanisms and Potential Clinical Implications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-83968-015-1.

- Li, Z.; Shen, J.; Chan, M.T.V.; Wu, W.K.K. TUG1: A Pivotal Oncogenic Long Non-coding RNA of Human Cancers. Cell Prolif. 2016, 49, 471–475.

- Khalil, A.M.; Guttman, M.; Huarte, M.; Garber, M.; Raj, A.; Rivea Morales, D.; Thomas, K.; Presser, A.; Bernstein, B.E.; van Oudenaarden, A.; et al. Many Human Large Intergenic Noncoding RNAs Associate with Chromatin-Modifying Complexes and Affect Gene Expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 11667–11672.

- Chen, D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, C.; Fang, B.; Chen, P. Abnormally Expressed Long Non-Coding RNAs in Prognosis of Osteosarcoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Bone Oncol. 2018, 13, 76–90.

- Cao, J.; Han, X.; Qi, X.; Jin, X.; Li, X. TUG1 Promotes Osteosarcoma Tumorigenesis by Upregulating EZH2 Expression via MiR-144-3p. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 51, 1115–1123.

- Ma, B.; Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Huang, M.; Lei, J.-B.; Fu, G.-H.; Liu, C.-X.; Lai, Q.-W.; Chen, Q.-Q.; Wang, Y.-L. Upregulation of Long Non-Coding RNA TUG1 Correlates with Poor Prognosis and Disease Status in Osteosarcoma. Tumour. Biol. 2016, 37, 4445–4455.

- Ström, O.; Borgström, F.; Kanis, J.A.; Compston, J.; Cooper, C.; McCloskey, E.V.; Jönsson, B. Osteoporosis: Burden, Health Care Provision and Opportunities in the EU: A Report Prepared in Collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch. Osteoporos 2011, 6, 59–155.

- Huang, G.; Zhao, G.; Xia, J.; Wei, Y.; Chen, F.; Chen, J.; Shi, J. FGF2 and FAM201A Affect the Development of Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head after Femoral Neck Fracture. Gene 2018, 652, 39–47.

- Silva, A.M.; Teixeira, J.H.; Almeida, M.I.; Gonçalves, R.M.; Barbosa, M.A.; Santos, S.G. Extracellular Vesicles: Immunomodulatory Messengers in the Context of Tissue Repair/Regeneration. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 98, 86–95.

- Pearson, M.J.; Jones, S.W. Review: Long Noncoding RNAs in the Regulation of Inflammatory Pathways in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoarthritis. Arthritis. Rheumatol. 2016, 68, 2575–2583.

- Tang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Yu, X.; Xue, Z.; Shen, N. The Role of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Rheumatic Diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2017, 13, 657–669.

- Song, J.; Kim, D.; Han, J.; Kim, Y.; Lee, M.; Jin, E.-J. PBMC and Exosome-Derived Hotair Is a Critical Regulator and Potent Marker for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 15, 121–126.

- Lao, M.-X.; Xu, H.-S. Involvement of Long Non-Coding RNAs in the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Chin. Med. J. 2020, 133, 941–950.

- Mao, X.; Su, Z.; Mookhtiar, A.K. Long Non-coding RNA: A Versatile Regulator of the Nuclear Factor-κB Signalling Circuit. Immunology 2017, 150, 379–388.

- Spurlock, C.F.; Tossberg, J.T.; Matlock, B.K.; Olsen, N.J.; Aune, T.M. Methotrexate Inhibits NF-ΚB Activity via LincRNA-P21 Induction. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, 2947–2957.

- Magagula, L.; Gagliardi, M.; Naidoo, J.; Mhlanga, M. Lnc-Ing Inflammation to Disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 953–962.

- Chen, B.; Yang, W.; Zhao, H.; Liu, K.; Deng, A.; Zhang, G.; Pan, K. Abnormal Expression of MiR-135b-5p in Bone Tissue of Patients with Osteoporosis and Its Role and Mechanism in Osteoporosis Progression. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 1042–1050.

- Cheung, W.H.; Miclau, T.; Chow, S.K.-H.; Yang, F.F.; Alt, V. Fracture Healing in Osteoporotic Bone. Injury 2016, 47 (Suppl. S2), S21–S26.

- Li, Q.S.; Meng, F.Y.; Zhao, Y.H.; Jin, C.L.; Tian, J.; Yi, X.J. Inhibition of MicroRNA-214-5p Promotes Cell Survival and Extracellular Matrix Formation by Targeting Collagen Type IV Alpha 1 in Osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 Cells. Bone Joint Res. 2017, 6, 464–471.

- Wang, C.; Zheng, G.-F.; Xu, X.-F. MicroRNA-186 Improves Fracture Healing through Activating the Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signalling Pathway by Inhibiting SMAD6 in a Mouse Model of Femoral Fracture. Bone Joint Res. 2019, 8, 550–562.

- Lee, W.Y.; Li, N.; Lin, S.; Wang, B.; Lan, H.Y.; Li, G. MiRNA-29b Improves Bone Healing in Mouse Fracture Model. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2016, 430, 97–107.

- Shi, L.; Feng, L.; Liu, Y.; Duan, J.-Q.; Lin, W.-P.; Zhang, J.-F.; Li, G. MicroRNA-218 Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Accelerates Bone Fracture Healing. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2018, 103, 227–236.

- Murata, K.; Ito, H.; Yoshitomi, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Fukuda, A.; Yoshikawa, J.; Furu, M.; Ishikawa, M.; Shibuya, H.; Matsuda, S. Inhibition of MiR-92a Enhances Fracture Healing via Promoting Angiogenesis in a Model of Stabilized Fracture in Young Mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 316–326.

- Bottani, M.; Banfi, G.; Lombardi, G. The Clinical Potential of Circulating MiRNAs as Biomarkers: Present and Future Applications for Diagnosis and Prognosis of Age-Associated Bone Diseases. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 589.

- Xu, J.-F.; Yang, G.; Pan, X.-H.; Zhang, S.-J.; Zhao, C.; Qiu, B.-S.; Gu, H.-F.; Hong, J.-F.; Cao, L.; Chen, Y.; et al. Altered MicroRNA Expression Profile in Exosomes during Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114627.

- Jiang, L.-B.; Tian, L.; Zhang, C.-G. Bone Marrow Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes Extracted from Osteoporosis Patients Inhibit Osteogenesis via MicroRNA-21/SMAD7. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 6221–6229.

- Song, H.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Qian, J.; Wang, Y.; Cui, J.; Weng, W.; Cao, L.; Chen, X.; Hu, Y.; et al. Reversal of Osteoporotic Activity by Endothelial Cell-Secreted Bone Targeting and Biocompatible Exosomes. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 3040–3048.

- Li, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, A.; Zhang, C.; Han, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, S.; Zhang, X.; Lv, F. Exosomal MiR-186 Derived from BMSCs Promote Osteogenesis through Hippo Signaling Pathway in Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 23.

- Chen, C.; Wang, D.; Moshaverinia, A.; Liu, D.; Kou, X.; Yu, W.; Yang, R.; Sun, L.; Shi, S. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation in Tight-Skin Mice Identifies MiR-151-5p as a Therapeutic Target for Systemic Sclerosis. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 559–577.

- Hu, H.; He, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, R.; Chen, J.; Lin, Y.; Shen, B. MicroRNA Alterations for Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment of Osteoporosis: A Comprehensive Review and Computational Functional Survey. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 181.

- Loeser, R.F.; Goldring, S.R.; Scanzello, C.R.; Goldring, M.B. Osteoarthritis: A Disease of the Joint as an Organ. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64, 1697–1707.

- Toh, W.S.; Lai, R.C.; Hui, J.H.P.; Lim, S.K. MSC Exosome as a Cell-Free MSC Therapy for Cartilage Regeneration: Implications for Osteoarthritis Treatment. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 67, 56–64.

- Jin, Z.; Ren, J.; Qi, S. Human Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes Overexpressing MicroRNA-26a-5p Alleviate Osteoarthritis via down-Regulation of PTGS2. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 78, 105946.

- Wang, R.; Xu, B.; Xu, H. TGF-Β1 Promoted Chondrocyte Proliferation by Regulating Sp1 through MSC-Exosomes Derived MiR-135b. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 2756–2765.

- Mao, G.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Chang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Liao, W.; Kang, Y. Exosomes Derived from MiR-92a-3p-Overexpressing Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Enhance Chondrogenesis and Suppress Cartilage Degradation via Targeting WNT5A. Stem. Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 247.

- Meng, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Kang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Long, D.; Hu, S.; Gu, M.; He, S.; et al. MicroRNA-193b-3p Regulates Chondrogenesis and Chondrocyte Metabolism by Targeting HDAC3. Theranostics 2018, 8, 2862–2883.

- Li, H.; Zheng, Q.; Xie, X.; Wang, J.; Zhu, H.; Hu, H.; He, H.; Lu, Q. Role of Exosomal Non-Coding RNAs in Bone-Related Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 811666.

- Rokavec, M.; Wu, W.; Luo, J.-L. IL6-Mediated Suppression of MiR-200c Directs Constitutive Activation of an Inflammatory Signaling Circuit That Drives Transformation and Tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell 2012, 45, 777–789.

- Zhou, F.; Wang, W.; Xing, Y.; Wang, T.; Xu, X.; Wang, J. NF-ΚB Target MicroRNAs and Their Target Genes in TNFα-Stimulated HeLa Cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1839, 344–354.

- Zhang, Z.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Duan, X.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Liao, W. Expression of MicroRNAs during Chondrogenesis of Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2012, 20, 1638–1646.

- Mao, G.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, P.; Zhao, X.; Lin, R.; Liao, W.; Kang, Y. Exosomal MiR-95-5p Regulates Chondrogenesis and Cartilage Degradation via Histone Deacetylase 2/8. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 5354–5366.

- Mao, G.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Chen, W.; Huang, G.; Meng, F.; Zhang, Z.; Kang, Y. MicroRNA-92a-3p Regulates the Expression of Cartilage-Specific Genes by Directly Targeting Histone Deacetylase 2 in Chondrogenesis and Degradation. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2017, 25, 521–532.

- Liu, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Fang, L.; Yuan, C.; Wang, X.; Lin, K. Breakthrough of Extracellular Vesicles in Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 22, 423–452.

- Jin, Z.; Ren, J.; Qi, S. Exosomal MiR-9-5p Secreted by Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Alleviates Osteoarthritis by Inhibiting Syndecan-1. Cell Tissue Res. 2020, 381, 99–114.

- Ni, Z.; Kuang, L.; Chen, H.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, B.; Ouyang, J.; Wu, J.; Zhou, S.; Chen, L.; Su, N.; et al. The Exosome-like Vesicles from Osteoarthritic Chondrocyte Enhanced Mature IL-1β Production of Macrophages and Aggravated Synovitis in Osteoarthritis. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 522.

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, S.; Zheng, Z.; Bian, Y.; Feng, B.; Weng, X. Chondrocytes-Derived Exosomal MiR-8485 Regulated the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathways to Promote Chondrogenic Differentiation of BMSCs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 523, 506–513.