| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chuande Huang | -- | 3726 | 2023-04-25 11:36:34 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 3726 | 2023-04-26 07:43:51 | | |

Video Upload Options

Hydrogen is an important green energy source and chemical raw material for various industrial processes. The major technique of hydrogen production is steam methane reforming (SMR), which suffers from high energy penalties and enormous CO2 emissions. As an alternative, chemical looping water-splitting (CLWS) technology represents an energy-efficient and environmentally friendly method for hydrogen production. The key to CLWS lies in the selection of suitable oxygen carriers (OCs) that hold outstanding sintering resistance, structural reversibility, and capability to release lattice oxygen and deoxygenate the steam for hydrogen generation.

1. Introduction

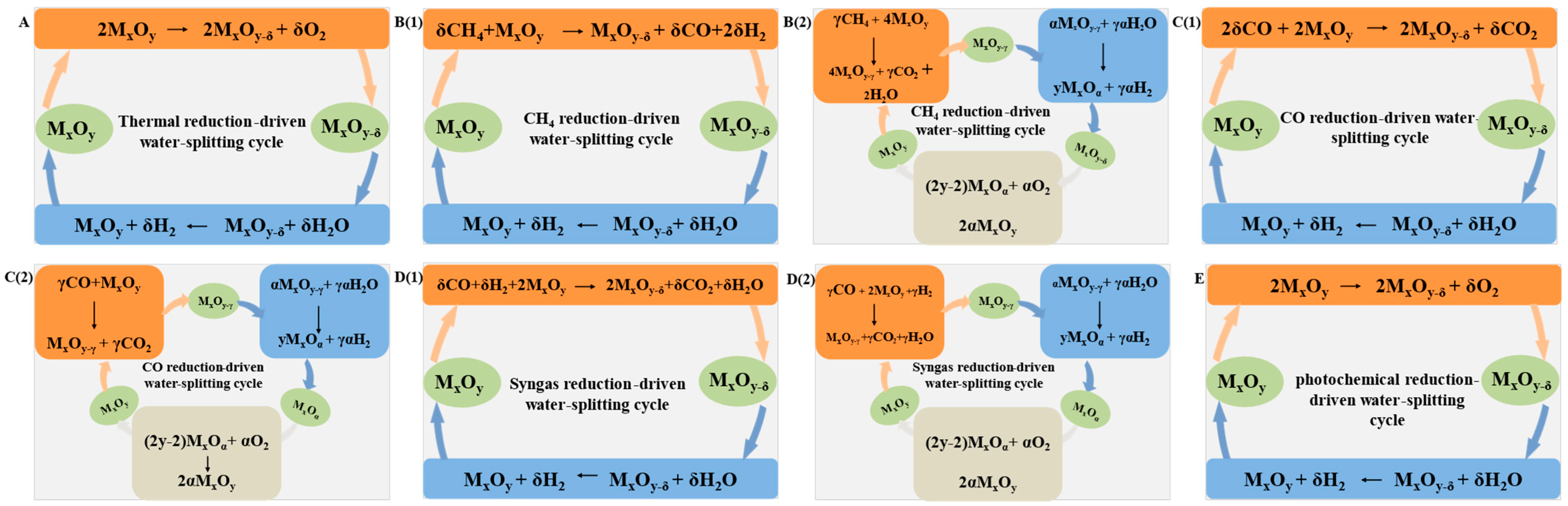

2. Processes for Chemical Looping Water-Splitting

2.1. Two-Step Thermochemical Water-Splitting

2.2. Methane Chemical Looping Process

2.2.1. Supported or Doped Iron Oxides

2.2.2. Supported or Doped Cerium Oxides

2.2.3. Perovskites

2.3. Chemical Looping Water Gas Shift Process

2.4. Syngas Chemical Looping Process

2.5. Photo-Thermochemical Cycle

3. Summary

Chemical looping water-splitting is promising for sustainable hydrogen production due to the virtue of decoupling a one-step reaction into two or three spatially separated reactions, which greatly simplifies the gas separation process and avoids the harsh conditions for direct water decomposition. To date, different processes have been developed, including a two-step thermochemical water-splitting (TCWS) cycle, methane chemical looping process, chemical looping water gas shift (CL-WGS) cycle, syngas chemical looping (SCL) process, and photo-thermochemical cycle (PTC), with attempts to reduce the energy penalty and CO2 emissions by altering the method to abstract the lattice oxygen from the OCs, wherein the key lies in the manufacture of suitable OCs.

For the two-step TCWS cycle, various OCs, such as iron oxides, zinc oxides, cerium oxides, and perovskite have been widely studied. Among them, cerium oxides have attracted particular attention due to their high structural stability and water-splitting conversion. However, the relatively low reduction degree during the redox cycle, rendering a low hydrogen yield (0.72~7.58 mL/g), greatly hampered its practical applications. Recent work showed that perovskite oxides are promising candidates for two-step TCWS with hydrogen yields of up to 3.13 to 10.71 mL/g, since their redox properties can be facilely modulated by tuning the A/B sites. This gives a clue that constructing composite materials to adjust the redox potential suitable for oxygen desorption and water-splitting should be the key for improving the hydrogen productivity.

Compared to the two-step TCWS cycle, introducing reducing gas, such as methane, carbon monoxide, and syngas, to reduce the oxygen carrier is capable of notably decreasing the reaction temperature to below 1000 °C while enhancing the available oxygen capacity, which significantly decreases the energy consumption, slows down the sintering of OCs, and improve the yield of hydrogen to 13.44~267.63 mL/g. As for methane-driven reduction, valuable syngas with H2/CO ratio of two for Fischer–Tropsch synthesis and methanol production is produced when a suitable OC is selected. Upon OCs with high reducibility applied, the reducing gaseous can be totally combusted with generation of high concentration CO2 (and H2O). All these processes greatly inhibit the side reactions and reduce the burden for gas separation and CO2 caption, rendering improved efficiency and lowered cost for hydrogen production. Among the investigated OCs, iron-based oxides are among the most studied materials due to the virtues of low-cost, environmentally benign features with the high capacity to donate lattice oxygen by varying the valence state of Fe cations.

At present, selection of OCs for CLWS reactions mainly relies on screening method. This is mainly ascribed to the harsh reaction conditions and dynamic structural evolution during redox reactions, which poses a huge challenge for comprehensively understanding the reaction mechanism and designing advanced OCs for CLWS reactions. Future studies should pay more attention to establish a more precise structure–function relationship with the help of in situ characterization, theoretical calculations, and thermodynamic analysis to provide a theoretical basis and development direction for the design of new efficient long-life OCs. Furthermore, according to the pioneering studies, the research focus of OCs is gradually transferred from simple metal oxides to composite oxides (e.g., perovskite) and mixed oxides due to the feasibility of modulating the redox properties by altering the composition of OCs or synergy between different oxides, which bypasses the shortcomings of single metal oxides, and improves the performance of hydrogen production. Therefore, exploring composite oxides to precisely control the metal–oxygen bond strength and mixed oxides to integrate the advantages of different oxides would be an effective strategy for further improving the redox performance of OCs.

References

- Bockris, J. The origin of ideas on a Hydrogen Economy and its solution to the decay of the environment. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2002, 27, 731–740.

- Safari, F.; Dincer, I. A review and comparative evaluation of thermochemical water splitting cycles for hydrogen production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 205, 112182.

- Alves, H.J.; Bley Junior, C.; Niklevicz, R.R.; Frigo, E.P.; Frigo, M.S.; Coimbra-Araújo, C.H. Overview of hydrogen production technologies from biogas and the applications in fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 5215–5225.

- Dincer, I.; Acar, C. Review and evaluation of hydrogen production methods for better sustainability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 11094–11111.

- Mahant, B.; Linga, P.; Kumar, R. Hydrogen Economy and Role of Hythane as a Bridging Solution: A Perspective Review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 15424–15454.

- Navarro, R.M.; Pena, M.A.; Fierro, J.L. Hydrogen production reactions from carbon feedstocks: Fossil fuels and biomass. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 3952–3991.

- Go, K.S.; Son, S.R.; Kim, S.D.; Kang, K.S.; Park, C.S. Hydrogen production from two-step steam methane reforming in a fluidized bed reactor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 1301–1309.

- Lee, K.B.; Beaver, M.G.; Caram, H.S.; Sircar, S. Novel Thermal-Swing Sorption-Enhanced Reaction Process Concept for Hydrogen Production by Low-Temperature Steam–Methane Reforming. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 5003–5014.

- Wang, J.; Sakanishi, K.; Saito, I.; Takarada, T.; Morishita, K. High-Yield Hydrogen Production by Steam Gasification of HyperCoal (Ash-Free Coal Extract) with Potassium Carbonate: Comparison with Raw Coal. Energy Fuels 2005, 19, 2114–2120.

- Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, G. Life cycle greenhouse gas assessment of hydrogen production via chemical looping combustion thermally coupled steam reforming. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 335–346.

- Li, J.; Cheng, W. Comparative life cycle energy consumption, carbon emissions and economic costs of hydrogen production from coke oven gas and coal gasification. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 27979–27993.

- Kodama, T.; Gokon, N. Thermochemical cycles for high-temperature solar hydrogen production. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 4048–4077.

- Kogan, A. Direct solar thermal splitting of water and on-site separation of the products-II. Experimental feasibility study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1998, 23, 89–98.

- Bilgen, E.; Ducarroir, M.; Foex, M.; Sibieude, F.; Trombe, F. Use of solar energy for direct and two-step water decomposition cycles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1977, 2, 251–257.

- Li, D.; Xu, R.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; Li, K. Chemical Looping Conversion of Gaseous and Liquid Fuels for Chemical Production: A Review. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 5381–5413.

- Moghtaderi, B. Review of the Recent Chemical Looping Process Developments for Novel Energy and Fuel Applications. Energy Fuels 2011, 26, 15–40.

- De Vos, Y.; Jacobs, M.; Van Der Voort, P.; Van Driessche, I.; Snijkers, F.; Verberckmoes, A. Development of Stable Oxygen Carrier Materials for Chemical Looping Processes—A Review. Catalysts 2020, 10, 926.

- Funk, J.E.; Reinstrom, R.M. Energy Requirements in Production of Hydrogen from Water. Ind. Eng. Chem. Process 1966, 5, 336–342.

- Krenzke, P.T.; Fosheim, J.R.; Davidson, J.H. Solar fuels via chemical-looping reforming. Sol. Energy 2017, 156, 48–72.

- Chen, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Cheng, F.; Tong, J.; Yang, M.; Jiang, Z.; Li, C. Sr- and Co-doped LaGaO3−δ with high O2 and H2 yields in solar thermochemical water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 6099–6112.

- de Leeuwe, C.; Hu, W.; Evans, J.; von Stosch, M.; Metcalfe, I.S. Production of high purity H2 through chemical-looping water–gas shift at reforming temperatures—The importance of non-stoichiometric oxygen carriers. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 423, 130174.

- Gupta, P.; Velazquez-Vargas, L.G.; Fan, L.-S. Syngas Redox (SGR) Process to Produce Hydrogen from Coal Derived Syngas. Energy Fuels 2007, 21, 2900–2908.

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Xu, C.; Zhou, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Cen, K. A novel photo-thermochemical cycle of water-splitting for hydrogen production based on TiO2−x/TiO2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 2215–2221.

- Li, F.; Fan, L.-S. Clean coal conversion processes—Progress and challenges. Energy Environ. Sci. 2008, 1, 248–267.

- Adanez, J.; Abad, A.; Garcia-Labiano, F.; Gayan, P.; de Diego, L.F. Progress in Chemical-Looping Combustion and Reforming technologies. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2012, 38, 215–282.

- Abanades, S. Metal Oxides Applied to Thermochemical Water-Splitting for Hydrogen Production Using Concentrated Solar Energy. ChemEngineering 2019, 3, 63.

- Muhich, C.L.; Ehrhart, B.D.; Al-Shankiti, I.; Ward, B.J.; Musgrave, C.B.; Weimer, A.W. A review and perspective of efficient hydrogen generation via solar thermal water splitting. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2016, 5, 261–287.

- Nakamura, T. Hydrogen production from water utilizing solar heat at high temperatures. Sol. Energy 1977, 19, 467–475.

- Steinfeld, A.; Sanders, S.; Palumbo, R. Design aspects of solar thermochemical engineering—A case study: Two-step water-splitting cycle using the Fe3O4/FeO redox system. Sol. Energy 1999, 65, 43–53.

- Han, S.B.; Kang, T.B.; Joo, O.S.; Jung, K.D. Water splitting for hydrogen production with ferrites. Sol. Energy 2007, 81, 623–628.

- Abanades, S.; Flamant, G. Thermochemical hydrogen production from a two-step solar-driven water-splitting cycle based on cerium oxides. Sol. Energy 2006, 80, 1611–1623.

- Chueh, W.C.; Falter, C.; Abbott, M.; Scipio, D.; Furler, P.; Haile, S.M.; Steinfeld, A. High-flux solar-driven thermochemical dissociation of CO2 and H2O using nonstoichiometric ceria. Science 2010, 330, 1797–1801.

- Zhu, X.; Li, K.; Neal, L.; Li, F. Perovskites as Geo-inspired Oxygen Storage Materials for Chemical Looping and Three-Way Catalysis: A Perspective. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 8213–8236.

- Takacs, M.; Hoes, M.; Caduff, M.; Cooper, T.; Scheffe, J.R.; Steinfeld, A. Oxygen nonstoichiometry, defect equilibria, and thermodynamic characterization of LaMnO3 perovskites with Ca/Sr A-site and Al B-site doping. Acta Mater. 2016, 103, 700–710.

- McDaniel, A.H.; Miller, E.C.; Arifin, D.; Ambrosini, A.; Coker, E.N.; O’Hayre, R.; Chueh, W.C.; Tong, J. Sr- and Mn-doped LaAlO3−δ for solar thermochemical H2 and CO production. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 2424–2428.

- Barcellos, D.R.; Sanders, M.D.; Tong, J.; McDaniel, A.H.; O’Hayre, R.P. BaCe0.25Mn0.75O3−δ—A promising perovskite-type oxide for solar thermochemical hydrogen production. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 3256–3265.

- Chuayboon, S.; Abanades, S.; Rodat, S. High-Purity and Clean Syngas and Hydrogen Production From Two-Step CH4 Reforming and H2O Splitting Through Isothermal Ceria Redox Cycle Using Concentrated Sunlight. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 00128.

- Wang, L.; Ma, T.; Chang, Z.; Li, H.; Fu, M.; Li, X. Solar fuels production via two-step thermochemical cycle based on Fe3O4/Fe with methane reduction. Sol. Energy 2019, 177, 772–781.

- He, F.; Li, F. Perovskite promoted iron oxide for hybrid water-splitting and syngas generation with exceptional conversion. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 535–539.

- Chuayboon, S.; Abanades, S.; Rodat, S. Syngas production via solar-driven chemical looping methane reforming from redox cycling of ceria porous foam in a volumetric solar reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 356, 756–770.

- Welte, M.; Warren, K.; Scheffe, J.R.; Steinfeld, A. Combined Ceria Reduction and Methane Reforming in a Solar-Driven Particle-Transport Reactor. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 10300–10308.

- Saha, D.; Grappe, H.A.; Chakraborty, A.; Orkoulas, G. Postextraction Separation, On-Board Storage, and Catalytic Conversion of Methane in Natural Gas: A Review. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11436–11499.

- Olivos-Suarez, A.I.; Szécsényi, À.; Hensen, E.J.M.; Ruiz-Martinez, J.; Pidko, E.A.; Gascon, J. Strategies for the Direct Catalytic Valorization of Methane Using Heterogeneous Catalysis: Challenges and Opportunities. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 2965–2981.

- He, Y.; Zhu, L.; Li, L.; Liu, G. Hydrogen and Power Cogeneration Based on Chemical Looping Combustion: Is It Capable of Reducing Carbon Emissions and the Cost of Production? Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 3501–3512.

- Zhu, X.; Wei, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, K. Ce–Fe oxygen carriers for chemical-looping steam methane reforming. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 4492–4501.

- De Vos, Y.; Jacobs, M.; Van Der Voort, P.; Van Driessche, I.; Snijkers, F.; Verberckmoes, A. Sustainable iron-based oxygen carriers for Chemical Looping for Hydrogen Generation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 1374–1391.

- Go, K.; Son, S.; Kim, S. Reaction kinetics of reduction and oxidation of metal oxides for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 5986–5995.

- Kang, K.-S.; Kim, C.-H.; Cho, W.-C.; Bae, K.-K.; Woo, S.-W.; Park, C.-S. Reduction characteristics of CuFe2O4 and Fe3O4 by methane; CuFe2O4 as an oxidant for two-step thermochemical methane reforming. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 4560–4568.

- Ku, Y.; Wu, H.-C.; Chiu, P.-C.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Kuo, Y.-L. Methane combustion by moving bed fuel reactor with Fe2O3/Al2O3 oxygen carriers. Appl. Energy 2014, 113, 1909–1915.

- Zhu, M.; Chen, S.; Ma, S.; Xiang, W. Carbon formation on iron-based oxygen carriers during CH4 reduction period in Chemical Looping Hydrogen Generation process. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 325, 322–331.

- Galinsky, N.L.; Huang, Y.; Shafiefarhood, A.; Li, F. Iron Oxide with Facilitated O2− Transport for Facile Fuel Oxidation and CO2 Capture in a Chemical Looping Scheme. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2013, 1, 364–373.

- Li, D.; Li, K.; Xu, R.; Wang, H.; Tian, D.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zeng, C.; Zeng, L. Ce1−xFexO2−δ catalysts for catalytic methane combustion: Role of oxygen vacancy and structural dependence. Catal. Today 2018, 318, 73–85.

- Han, Y.; Tian, M.; Wang, C.; Kang, Y.; Kang, L.; Su, Y.; Huang, C.; Zong, T.; Lin, J.; Hou, B.; et al. Highly Active and Anticoke Ni/CeO2 with Ultralow Ni Loading in Chemical Looping Dry Reforming via the Strong Metal–Support Interaction. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 17276–17288.

- Murray, E.P.; Tsai, T.; Barnett, S.A. A direct-methane fuel cell with a ceria-based anode. Nature 1999, 400, 649–651.

- Ruan, C.; Huang, Z.-Q.; Lin, J.; Li, L.; Liu, X.; Tian, M.; Huang, C.; Chang, C.-R.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Synergy of the catalytic activation on Ni and the CeO2–TiO2/Ce2Ti2O7 stoichiometric redox cycle for dramatically enhanced solar fuel production. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 767–779.

- Rydén, M.; Leion, H.; Mattisson, T.; Lyngfelt, A. Combined oxides as oxygen-carrier material for chemical-looping with oxygen uncoupling. Appl. Energy 2014, 113, 1924–1932.

- Long, Y.; Yang, K.; Gu, Z.; Lin, S.; Li, D.; Zhu, X.; Wang, H.; Li, K. Hydrogen generation from water splitting over polyfunctional perovskite oxygen carriers by using coke oven gas as reducing agent. Appl. Catal. B 2022, 301, 120778.

- Lee, M.; Lim, H.S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J.W. Enhancement of highly-concentrated hydrogen productivity in chemical looping steam methane reforming using Fe-substituted LaCoO3. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 207, 112507.

- Zhang, X.; Su, Y.; Pei, C.; Zhao, Z.-J.; Liu, R.; Gong, J. Chemical looping steam reforming of methane over Ce-doped perovskites. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 223, 115707.

- Zhang, X.; Pei, C.; Chang, X.; Chen, S.; Liu, R.; Zhao, Z.J.; Mu, R.; Gong, J. FeO6 Octahedral Distortion Activates Lattice Oxygen in Perovskite Ferrite for Methane Partial Oxidation Coupled with CO2 Splitting. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 11540–11549.

- Wang, S.; Guan, B.Y.; Lou, X.W.D. Construction of ZnIn2S4-In2O3 Hierarchical Tubular Heterostructures for Efficient CO2 Photoreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 5037–5040.

- Bahmanpour, A.M.; Héroguel, F.; Kılıç, M.; Baranowski, C.J.; Artiglia, L.; Röthlisberger, U.; Luterbacher, J.S.; Kröcher, O. Cu–Al Spinel as a Highly Active and Stable Catalyst for the Reverse Water Gas Shift Reaction. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 6243–6251.

- Bohn, C.D.; Cleeton, J.P.; Müller, C.R.; Chuang, S.Y.; Scott, S.A.; Dennis, J.S. Stabilizing Iron Oxide Used in Cycles of Reduction and Oxidation for Hydrogen Production. Energy Fuels 2010, 24, 4025–4033.

- Liu, W.; Dennis, J.S.; Scott, S.A. The Effect of Addition of ZrO2 to Fe2O3 for Hydrogen Production by Chemical Looping. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 16597–16609.

- Kierzkowska, A.M.; Bohn, C.D.; Scott, S.A.; Cleeton, J.P.; Dennis, J.S.; Müller, C.R. Development of Iron Oxide Carriers for Chemical Looping Combustion Using Sol–Gel. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 5383–5391.

- Chen, S.; Shi, Q.; Xue, Z.; Sun, X.; Xiang, W. Experimental investigation of chemical-looping hydrogen generation using Al2O3 or TiO2-supported iron oxides in a batch fluidized bed. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 8915–8926.

- Hafizi, A.; Rahimpour, M. Inhibiting Fe–Al Spinel Formation on a Narrowed Mesopore-Sized MgAl2O4 Support as a Novel Catalyst for H2 Production in Chemical Looping Technology. Catalysts 2018, 8, 27.

- Do, J.Y.; Son, N.; Park, N.-K.; Kwak, B.S.; Baek, J.-I.; Ryu, H.-J.; Kang, M. Reliable oxygen transfer in MgAl2O4 spinel through the reversible formation of oxygen vacancies by Cu2+/Fe3+ anchoring. Appl. Energy 2018, 219, 138–150.

- Liu, F.; Wu, F.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y. Experimental and theoretical insights into the mechanism of spinel CoFe2O4 reduction in CO chemical looping combustion. Fuel 2021, 293, 120473.

- Huang, Z.; Deng, Z.; Chen, D.; Wei, G.; He, F.; Zhao, K.; Zheng, A.; Zhao, Z.; Li, H. Exploration of Reaction Mechanisms on Hydrogen Production through Chemical Looping Steam Reforming Using NiFe2O4 Oxygen Carrier. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 11621–11632.

- Kim, Y.; Lim, H.S.; Lee, M.; Kim, M.; Kang, D.; Lee, J.W. Enhanced Morphological Preservation and Redox Activity in Al-Incorporated NiFe2O4 for Chemical Looping Hydrogen Production. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 14800–14810.

- Cui, D.; Li, M.; Qiu, Y.; Ma, L.; Zeng, D.; Xiao, R. Improved hydrogen production with 100% fuel conversion through the redox cycle of ZnFeAlOx oxygen carrier in chemical looping scheme. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 400, 125769.

- Hirabayashi, D.; Yoshikawa, T.; Mochizuki, K.; Suzuki, K.; Sakai, Y. Formation of brownmillerite type calcium ferrite (Ca2Fe2O5) and catalytic properties in propylene combustion. Catal. Lett. 2006, 110, 155–160.

- Shah, V.; Mohapatra, P.; Fan, L.-S. Thermodynamic and Process Analyses of Syngas Production Using Chemical Looping Reforming Assisted by Flexible Dicalcium Ferrite-Based Oxygen Carrier Regeneration. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 6490–6500.

- Ismail, M.; Liu, W.; Chan, M.S.C.; Dunstan, M.T.; Scott, S.A. Synthesis, Application, and Carbonation Behavior of Ca2Fe2O5 for Chemical Looping H2 Production. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 6220–6232.

- Chan, M.S.C.; Liu, W.; Ismail, M.; Yang, Y.; Scott, S.A.; Dennis, J.S. Improving hydrogen yields, and hydrogen:steam ratio in the chemical looping production of hydrogen using Ca2Fe2O5. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 296, 406–411.

- Sun, Z.; Chen, S.; Hu, J.; Chen, A.; Rony, A.H.; Russell, C.K.; Xiang, W.; Fan, M.; Darby Dyar, M.; Dklute, E.C. Ca2Fe2O5: A promising oxygen carrier for CO/CH4 conversion and almost-pure H2 production with inherent CO2 capture over a two-step chemical looping hydrogen generation process. Appl. Energy 2018, 211, 431–442.

- You, S.; Ok, Y.S.; Chen, S.S.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Kwon, E.E.; Lee, J.; Wang, C.H. A critical review on sustainable biochar system through gasification: Energy and environmental applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 246, 242–253.

- Hu, Z.; Miao, Z.; Chen, H.; Wu, J.; Wu, W.; Ren, Y.; Jiang, E. Chemical looping gasification of biochar to produce hydrogen-rich syngas using Fe/Ca-based oxygen carrier prepared by coprecipitation. J. Energy Inst. 2021, 94, 157–166.

- Bracciale, M.P.; Damizia, M.; De Filippis, P.; de Caprariis, B. Clean Syngas and Hydrogen Co-Production by Gasification and Chemical Looping Hydrogen Process Using MgO-Doped Fe2O3 as Redox Material. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1273.

- Li, F.; Kim, H.R.; Sridhar, D.; Wang, F.; Zeng, L.; Chen, J.; Fan, L.S. Syngas Chemical Looping Gasification Process: Oxygen Carrier Particle Selection and Performance. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 4182–4189.

- Li, F.; Zeng, L.; Velazquez-Vargas, L.G.; Yoscovits, Z.; Fan, L.-S. Syngas chemical looping gasification process: Bench-scale studies and reactor simulations. AlChE J. 2010, 56, 2186–2199.

- Aston, V.J.; Evanko, B.W.; Weimer, A.W. Investigation of novel mixed metal ferrites for pure H2 and CO2 production using chemical looping. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 9085–9096.

- Liu, S.; He, F.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, A.; Feng, Y.; Shen, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, H.; Glarborg, P. Screening of NiFe2O4 Nanoparticles as Oxygen Carrier in Chemical Looping Hydrogen Production. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 4251–4262.