| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yoshimitsu Kiiriyama | -- | 1946 | 2023-04-20 02:59:26 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 1946 | 2023-04-21 03:28:37 | | |

Video Upload Options

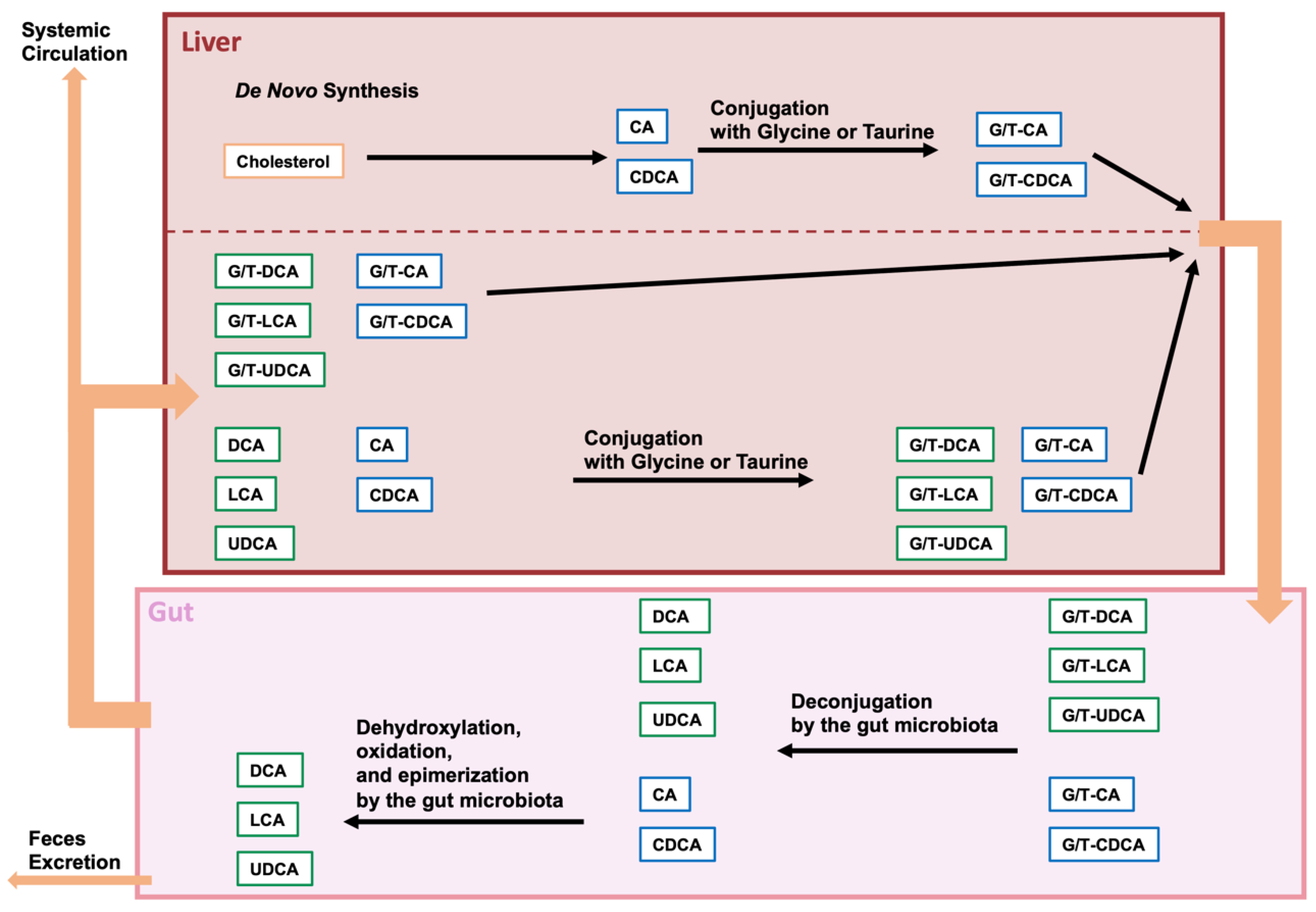

Bile acids (BAs) are amphiphilic steroidal molecules generated from cholesterol in the liver and facilitate the digestion and absorption of fat-soluble substances in the gut. Some BAs in the intestine are modified by the gut microbiota. Because BAs are modified in a variety of ways by different types of bacteria present in the gut microbiota, changes in the gut microbiota can affect the metabolism of BAs in the host. Although most BAs absorbed from the gut are transferred to the liver, some are transferred to the systemic circulation. Furthermore, BAs have also been detected in the brain and are thought to migrate into the brain through the systemic circulation. Although BAs are known to affect a variety of physiological functions by acting as ligands for various nuclear and cell-surface receptors, BAs have also been found to act on mitochondria and autophagy in the cell.

1. Introduction

2. BAs and Gut Microbiota

2.1. Bile Acid Modification by the Gut Microbiota

2.2. Analysis of the Composition of the Gut Microbiota and Bacterial Species with Enzymes That Modify BAs

3. Microbiota-Modified BAs in Neurodegenerative Diseases

3.1. Alzheimer’s Disease

3.2. Parkinson’s Disease

3.3. Huntington’s Disease

References

- Di Ciaula, A.; Garruti, G.; Baccetto, R.L.; Molina-Molina, E.; Bonfrate, L.; Wang, D.Q.-H.; Portincasa, P. Bile Acid Physiology. Ann. Hepatol. 2017, 16, S4–S14.

- Li, T.; Chiang, J.Y.L. Bile Acid Signaling in Metabolic Disease and Drug Therapy. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014, 66, 948–983.

- Vallim, T.Q.D.A.; Tarling, E.J.; Edwards, P.A. Pleiotropic Roles of Bile Acids in Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 657–669.

- Ridlon, J.M.; Kang, D.J.; Hylemon, P.B. Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria. J. Lipid Res. 2006, 47, 241–259.

- Larabi, A.B.; Masson, H.L.P.; Bäumler, A.J. Bile acids as modulators of gut microbiota composition and function. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2172671.

- Perino, A.; Demagny, H.; Velazquez-Villegas, L.A.; Schoonjans, K. Molecular physiology of bile acid signaling in health, disease, and aging. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 683–731.

- Kiriyama, Y.; Nochi, H. Physiological Role of Bile Acids Modified by the Gut Microbiome. Microorganisms 2021, 10, 68.

- Kiriyama, Y.; Nochi, H. The Biosynthesis, Signaling, and Neurological Functions of Bile Acids. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 232.

- Russell, D.W. Fifty years of advances in bile acid synthesis and metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2009, 50, S120–S125.

- Katafuchi, T.; Makishima, M. Molecular Basis of Bile Acid-FXR-FGF15/19 Signaling Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6046.

- Pandak, W.M.; Kakiyama, G. The acidic pathway of bile acid synthesis: Not just an alternative pathway. Liver Res. 2019, 3, 88–98.

- Styles, N.A.; Shonsey, E.M.; Falany, J.L.; Guidry, A.L.; Barnes, S.; Falany, C.N. Carboxy-terminal mutations of bile acid CoA:N-acyltransferase alter activity and substrate specificity. J. Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 1133–1143.

- Jones, B.V.; Begley, M.; Hill, C.; Gahan, C.G.M.; Marchesi, J.R. Functional and comparative metagenomic analysis of bile salt hydrolase activity in the human gut microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13580–13585.

- O’Flaherty, S.; Crawley, A.B.; Theriot, C.M.; Barrangou, R. The Lactobacillus Bile Salt Hydrolase Repertoire Reveals Niche-Specific Adaptation. Msphere 2018, 3, e00140-18.

- Clarke, G.; Sandhu, K.V.; Griffin, B.T.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F.; Hyland, N.P. Gut Reactions: Breaking Down Xenobiotic–Microbiome Interactions. Pharmacol. Rev. 2019, 71, 198–224.

- Rivière, A.; Selak, M.; Lantin, D.; Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L. Bifidobacteria and Butyrate-Producing Colon Bacteria: Importance and Strategies for Their Stimulation in the Human Gut. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 979.

- Guo, X.; Okpara, E.S.; Hu, W.; Yan, C.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Q.; Chiang, J.Y.L.; Han, S. Interactive Relationships between Intestinal Flora and Bile Acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8343.

- Begley, M.; Hill, C.; Gahan, C.G.M. Bile Salt Hydrolase Activity in Probiotics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 1729–1738.

- Ramírez-Pérez, O.; Cruz-Ramón, V.; Chinchilla-López, P.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in Bile Acid Metabolism. Ann. Hepatol. 2017, 16, s15–s20.

- Li, M.; Liu, S.; Wang, M.; Hu, H.; Yin, J.; Liu, C.; Huang, Y. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis Associated with Bile Acid Metabolism in Neonatal Cholestasis Disease. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7686.

- Majait, S.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Kemper, M.; Soeters, M. The Black Box Orchestra of Gut Bacteria and Bile Acids: Who Is the Conductor? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1816.

- Song, Z.; Cai, Y.; Lao, X.; Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Cui, Y.; Kalavagunta, P.K.; Liao, J.; Jin, L.; Shang, J.; et al. Taxonomic profiling and populational patterns of bacterial bile salt hydrolase (BSH) genes based on worldwide human gut microbiome. Microbiome 2019, 7, 9.

- Doden, H.; Ridlon, J. Microbial Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenases: From Alpha to Omega. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 469.

- Wise, J.L.; Cummings, B.P. The 7-α-dehydroxylation pathway: An integral component of gut bacterial bile acid metabolism and potential therapeutic target. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1093420.

- Guzior, D.V.; Quinn, R.A. Review: Microbial transformations of human bile acids. Microbiome 2021, 9, 140.

- Spichak, S.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.; Berding, K.; Vlckova, K.; Clarke, G.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Mining microbes for mental health: Determining the role of microbial metabolic pathways in human brain health and disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 125, 698–761.

- Ghezzi, L.; Cantoni, C.; Rotondo, E.; Galimberti, D. The Gut Microbiome–Brain Crosstalk in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1486.

- Jansson, J.K.; Baker, E.S. A multi-omic future for microbiome studies. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16049.

- Jovel, J.; Patterson, J.; Wang, W.; Hotte, N.; O’Keefe, S.; Mitchel, T.; Perry, T.; Kao, D.; Mason, A.L.; Madsen, K.L.; et al. Characterization of the Gut Microbiome Using 16S or Shotgun Metagenomics. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 459.

- Laudadio, I.; Fulci, V.; Palone, F.; Stronati, L.; Cucchiara, S.; Carissimi, C. Quantitative Assessment of Shotgun Metagenomics and 16S rDNA Amplicon Sequencing in the Study of Human Gut Microbiome. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 2018, 22, 248–254.

- D’Argenio, V. Human Microbiome Acquisition and Bioinformatic Challenges in Metagenomic Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 383.

- Vogt, N.M.; Kerby, R.L.; Dill-McFarland, K.A.; Harding, S.J.; Merluzzi, A.P.; Johnson, S.C.; Carlsson, C.M.; Asthana, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; et al. Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13537.

- Liu, P.; Wu, L.; Peng, G.; Han, Y.; Tang, R.; Ge, J.; Zhang, L.; Jia, L.; Yue, S.; Zhou, K.; et al. Altered microbiomes distinguish Alzheimer’s disease from amnestic mild cognitive impairment and health in a Chinese cohort. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 80, 633–643.

- Haran, J.P.; Bhattarai, S.K.; Foley, S.E.; Dutta, P.; Ward, D.V.; Bucci, V.; McCormick, B.A. Alzheimer’s Disease Microbiome Is Associated with Dysregulation of the Anti-Inflammatory P-Glycoprotein Pathway. Mbio 2019, 10, e00632-19.

- Bedarf, J.R.; Hildebrand, F.; Coelho, L.P.; Sunagawa, S.; Bahram, M.; Goeser, F.; Bork, P.; Wüllner, U. Functional implications of microbial and viral gut metagenome changes in early stage L-DOPA-naïve Parkinson’s disease patients. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 39.

- Li, C.; Cui, L.; Yang, Y.; Miao, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Cui, G.; Zhang, Y. Gut Microbiota Differs Between Parkinson’s Disease Patients and Healthy Controls in Northeast China. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 171.

- Barichella, M.; Severgnini, M.; Cilia, R.; Cassani, E.; Bolliri, C.; Caronni, S.; Ferri, V.; Cancello, R.; Ceccarani, C.; Faierman, S.; et al. Unraveling gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 2018, 34, 396–405.

- Du, G.; Dong, W.; Yang, Q.; Yu, X.; Ma, J.; Gu, W.; Huang, Y. Altered Gut Microbiota Related to Inflammatory Responses in Patients With Huntington’s Disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 603594.

- Wasser, C.I.; Mercieca, E.-C.; Kong, G.; Hannan, A.J.; McKeown, S.J.; Glikmann-Johnston, Y.; Stout, J.C. Gut dysbiosis in Huntington’s disease: Associations among gut microbiota, cognitive performance and clinical outcomes. Brain Commun. 2020, 2, 110.

- Baloni, P.; Funk, C.C.; Yan, J.; Yurkovich, J.T.; Kueider-Paisley, A.; Nho, K.; Heinken, A.; Jia, W.; Mahmoudiandehkordi, S.; Louie, G.; et al. Metabolic Network Analysis Reveals Altered Bile Acid Synthesis and Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Rep. Med. 2020, 1, 100138.

- Mano, N.; Goto, T.; Uchida, M.; Nishimura, K.; Ando, M.; Kobayashi, N.; Goto, J. Presence of protein-bound unconjugated bile acids in the cytoplasmic fraction of rat brain. J. Lipid Res. 2004, 45, 295–300.

- Pan, X.; Elliott, C.T.; McGuinness, B.; Passmore, P.; Kehoe, P.G.; Hölscher, C.; McClean, P.L.; Graham, S.F.; Green, B.D. Metabolomic Profiling of Bile Acids in Clinical and Experimental Samples of Alzheimer’s Disease. Metabolites 2017, 7, 28.

- Mertens, K.L.; Kalsbeek, A.; Soeters, M.R.; Eggink, H.M. Bile Acid Signaling Pathways from the Enterohepatic Circulation to the Central Nervous System. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 617.

- Higashi, T.; Watanabe, S.; Tomaru, K.; Yamazaki, W.; Yoshizawa, K.; Ogawa, S.; Nagao, H.; Minato, K.; Maekawa, M.; Mano, N. Unconjugated bile acids in rat brain: Analytical method based on LC/ESI-MS/MS with chemical derivatization and estimation of their origin by comparison to serum levels. Steroids 2017, 125, 107–113.

- Kamp, F.; Hamilton, J.A. Movement of fatty acids, fatty acid analogs, and bile acids across phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 11074–11085.

- Monteiro-Cardoso, V.F.; Corlianò, M.; Singaraja, R.R. Bile Acids: A Communication Channel in the Gut-Brain Axis. NeuroMol. Med. 2020, 23, 99–117.

- Benedetti, A.; Di Sario, A.; Marucci, L.; Svegliati-Baroni, G.; Schteingart, C.D.; Ton-Nu, H.T.; Hofmann, A.F. Carrier-mediated transport of conjugated bile acids across the basolateral membrane of biliary epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 1997, 272, G1416–G1424.

- St-Pierre, M.V.; Kullak-Ublick, G.A.; Hagenbuch, B.; Meier, P.J. Transport of Bile Acids in Hepatic and Non-Hepatic Tissues. J. Exp. Biol. 2001, 204, 1673–1686.

- Holtzman, D.M.; Morris, J.C.; Goate, A.M. Alzheimer’s Disease: The Challenge of the Second Century. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 77sr1.

- Vassar, R.; Cole, S. The Basic Biology of BACE1: A Key Therapeutic Target for Alzheimers Disease. Curr. Genom. 2007, 8, 509–530.

- Tomita, T. Molecular mechanism of intramembrane proteolysis by γ-secretase. J. Biochem. 2014, 156, 195–201.

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Song, Y.-Q.; Tu, J. Autophagy in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis: Therapeutic potential and future perspectives. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 72, 101464.

- Marksteiner, J.; Blasko, I.; Kemmler, G.; Koal, T.; Humpel, C. Bile acid quantification of 20 plasma metabolites identifies lithocholic acid as a putative biomarker in Alzheimer’s disease. Metabolomics 2017, 14, 1.

- Mulak, A. Bile Acids as Key Modulators of the Brain-Gut-Microbiota Axis in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 84, 461–477.

- Nunes, A.F.; Amaral, J.D.; Lo, A.C.; Fonseca, M.B.; Viana, R.J.; Callaerts-Vegh, Z.; D’Hooge, R.; Rodrigues, C.M. TUDCA, a bile acid, attenuates amyloid precursor protein processing and amyloid-β deposition in APP/PS1 mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012, 45, 440–454.

- Lo, A.C.; Callaerts-Vegh, Z.; Nunes, A.F.; Rodrigues, C.M.; D’Hooge, R. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) supplementation prevents cognitive impairment and amyloid deposition in APP/PS1 mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 50, 21–29.

- Jankovic, J. Parkinson’s disease: Clinical features and diagnosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2008, 79, 368–376.

- Brichta, L.; Greengard, P.; Flajolet, M. Advances in the pharmacological treatment of Parkinson’s disease: Targeting neurotransmitter systems. Trends Neurosci. 2013, 36, 543–554.

- Jin, S.M.; Lazarou, M.; Wang, C.; Kane, L.A.; Narendra, D.P.; Youle, R.J. Mitochondrial membrane potential regulates PINK1 import and proteolytic destabilization by PARL. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 191, 933–942.

- Kiriyama, Y.; Nochi, H. The Function of Autophagy in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 26797–26812.

- Eldeeb, M.A.; Thomas, R.A.; Ragheb, M.A.; Fallahi, A.; Fon, E.A. Mitochondrial quality control in health and in Parkinson’s disease. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 1721–1755.

- Yakhine-Diop, S.M.; Morales-García, J.A.; Niso-Santano, M.; González-Polo, R.A.; Uribe-Carretero, E.; Martinez-Chacon, G.; Durand, S.; Maiuri, M.C.; Aiastui, A.; Zulaica, M.; et al. Metabolic alterations in plasma from patients with familial and idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Aging 2020, 12, 16690–16708.

- Shao, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Li, S.; Xu, G.; Le, W. Comprehensive metabolic profiling of Parkinson’s disease by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Mol. Neurodegener. 2021, 16, 4.

- Zhao, H.; Wang, C.; Zhao, N.; Li, W.; Yang, Z.; Liu, X.; Le, W.; Zhang, X. Potential biomarkers of Parkinson’s disease revealed by plasma metabolic profiling. J. Chromatogr. B 2018, 1081–1082, 101–108.

- Dayalu, P.; Albin, R.L. Huntington Disease. Neurol. Clin. 2015, 33, 101–114.

- Bates, G.P.; Dorsey, R.; Gusella, J.F.; Hayden, M.R.; Kay, C.; Leavitt, B.R.; Nance, M.; Ross, C.A.; Scahill, R.I.; Wetzel, R.; et al. Huntington Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2015, 1, 15005.

- Rui, Y.-N.; Xu, Z.; Patel, B.; Chen, Z.; Chen, D.; Tito, A.; David, G.; Sun, Y.; Stimming, E.F.; Bellen, H.J.; et al. Huntingtin functions as a scaffold for selective macroautophagy. Nature 2015, 17, 262–275.

- Steffan, J.S. Does Huntingtin play a role in selective macroautophagy? Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 3401–3413.

- Wanker, E.E.; Ast, A.; Schindler, F.; Trepte, P.; Schnoegl, S. The pathobiology of perturbed mutant huntingtin protein–protein interactions in Huntington’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2019, 151, 507–519.

- Franco-Iborra, S.; Plaza-Zabala, A.; Montpeyo, M.; Sebastian, D.; Vila, M.; Martinez-Vicente, M. Mutant HTT (huntingtin) impairs mitophagy in a cellular model of Huntington disease. Autophagy 2020, 17, 672–689.

- Túnez, I.; Tasset, I.; La Cruz, V.P.-D.; Santamaría, A. 3-Nitropropionic Acid as a Tool to Study the Mechanisms Involved in Huntington’s Disease: Past, Present and Future. Molecules 2010, 15, 878–916.

- Brouillet, E.; Jacquard, C.; Bizat, N.; Blum, D. 3-Nitropropionic acid: A mitochondrial toxin to uncover physiopathological mechanisms underlying striatal degeneration in Huntington’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2005, 95, 1521–1540.

- Keene, C.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Eich, T.; Linehan-Stieers, C.; Abt, A.; Kren, B.T.; Steer, C.J.; Low, W.C. A Bile Acid Protects against Motor and Cognitive Deficits and Reduces Striatal Degeneration in the 3-Nitropropionic Acid Model of Huntington’s Disease. Exp. Neurol. 2001, 171, 351–360.