Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Paul David | -- | 1609 | 2023-04-17 12:21:20 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | + 1 word(s) | 1610 | 2023-04-18 03:11:44 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

David, P.; Mittelstädt, A.; Kouhestani, D.; Anthuber, A.; Kahlert, C.; Sohn, K.; Weber, G.F. Liquid Biopsy in Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43117 (accessed on 13 January 2026).

David P, Mittelstädt A, Kouhestani D, Anthuber A, Kahlert C, Sohn K, et al. Liquid Biopsy in Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43117. Accessed January 13, 2026.

David, Paul, Anke Mittelstädt, Dina Kouhestani, Anna Anthuber, Christoph Kahlert, Kai Sohn, Georg F. Weber. "Liquid Biopsy in Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43117 (accessed January 13, 2026).

David, P., Mittelstädt, A., Kouhestani, D., Anthuber, A., Kahlert, C., Sohn, K., & Weber, G.F. (2023, April 17). Liquid Biopsy in Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43117

David, Paul, et al. "Liquid Biopsy in Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease." Encyclopedia. Web. 17 April, 2023.

Copy Citation

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers are a common cancer, affecting both men and women, normally diagnosed through tissue biopsies in combination with imaging techniques and standardized biomarkers leading to patient selection for local or systemic therapies. Liquid biopsies (LBs)—due to their non-invasive nature as well as low risk—are the current focus of cancer research and could be a promising tool for early cancer detection and treatment surveillance, thus leading to better patient outcomes.

liquid biopsy

circulating tumor cells (CTCs)

circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)

tumor exosomes

tumor-educated blood platelets (TEPs)

organoids

gastrointestinal cancer

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers are responsible for more cancer-related deaths than lung and breast cancer. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the major type of GI cancer, with 1.9 million new cases diagnosed worldwide in 2020, making it after lung and breast cancer the third most common cancer of all organs. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer, in the same year, 1.1 million new cases of gastric cancer, 900,000 new cases of liver cancer, 600,000 new cases of esophageal cancer, and 500,000 new cases of pancreatic cancer were diagnosed across the globe [1].

Although the prognosis of many GI cancers has improved over the past decades [2][3], a late cancer diagnosis is still the leading reason for cancer-related deaths among all GI cancers [4]. Current research focuses therefore on improving early cancer diagnosis, possibly leading to better outcomes among all GI cancers [5][6]. So far, endoscopic or CT-guided solid biopsies in combination with so-called serum-based tumor biomarkers are primary methods for the diagnosis of GI cancers [7]. Thereby, solid biopsies are considered the gold standard strategy capable of classifying tumors, identifying the mutational status, and providing prognostic information. However, these methods have some limitations, e.g., obtaining insufficient or inaccurate tissue samples possibly leading to false-positive or false-negative results. In addition, tissue biopsies might cause harm to the patient. However, recent studies suggest tissue biopsies taken from a single cancer nodule or single metastatic lesion may fail to represent the entire tumor heterogeneity within the patient, possibly being one of the main reasons for the failure of current targeted therapies [8][9][10][11][12][13]. To date, several serum-based biomarkers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), carbohydrate antigen 72-4 (CA72-4), carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125), and alpha-feto protein (AFP) have been identified and widely used for diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring of potential recurrence of GI cancers [14][15]. Although, due to the limit of specificity and sensitivity most of these biomarkers are not useful for early cancer detection [16]. Therefore, LB emerged as a promising tool for early detection, treatment selection, and real-time prognosis.

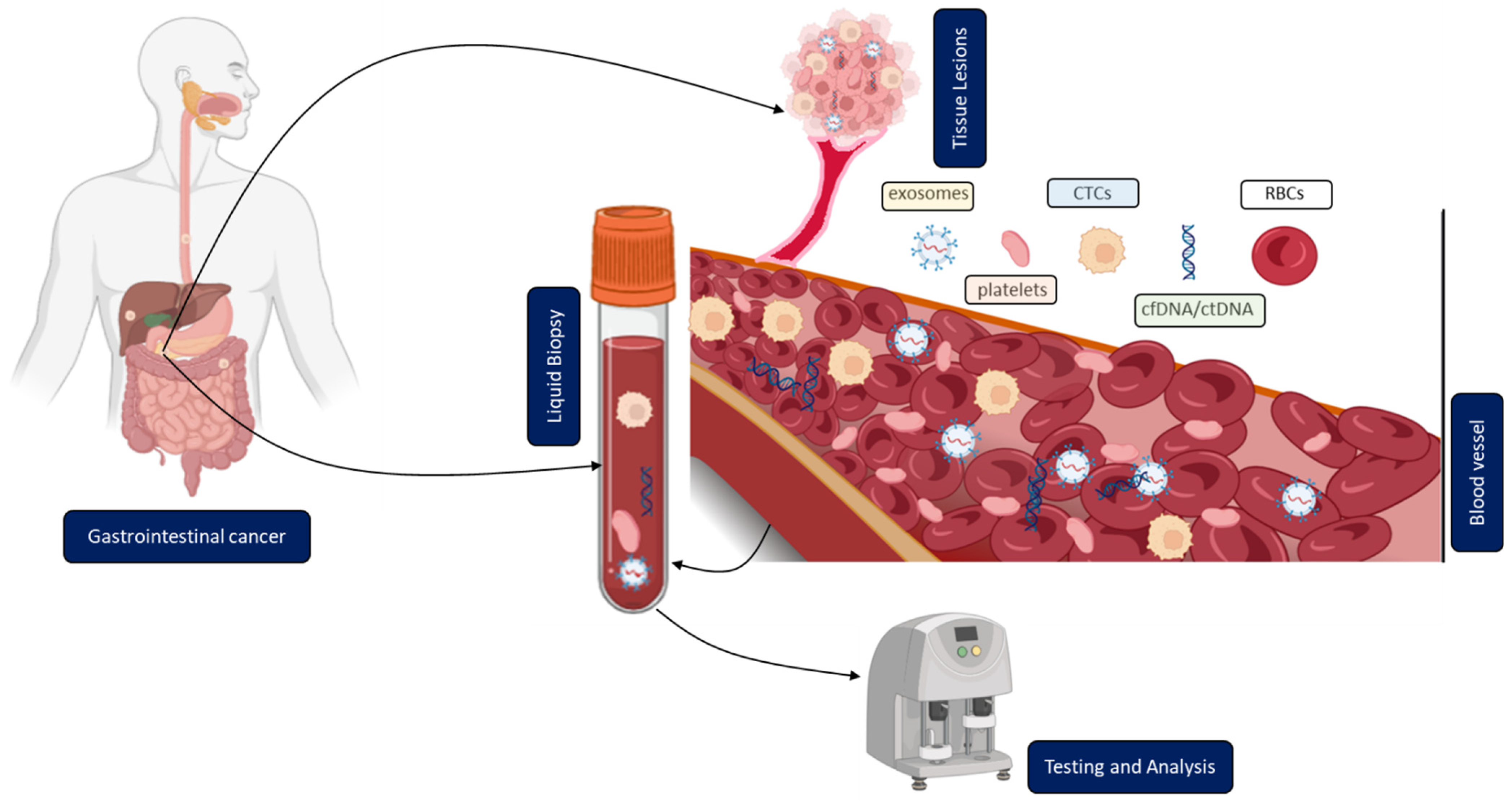

In contrast to solid biopsy, LB is a minimally invasive approach enabling the real-time monitoring and early uncovering of alterations in cells or cell products shed from malignant lesions into the body fluids (Figure 1). LB analysis can identify multiple heterogeneous resistance mechanisms in single patients compared to solid biopsy. Furthermore, LB facilitates the choice of the right treatment and observation of the treatment response. Due to the minimally invasive nature of LB, the resulting complications from obtaining solid biopsies could be prevented. A typical LB sample is taken from any biological fluid such as blood, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, or urine. LB materials derived from peripheral blood have been investigated extensively. LB analysis from blood contains enrichment and isolation of CTCs, circulating blood platelets, ctDNA, and other tumor genetic material such as extracellular vesicles. As of today, several LB technologies have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for malignancies such as metastatic lung, breast, prostate, or colorectal cancer: CELLSEARCH CTC test using circulating tumor cells from Veridex, Guardant360 CDx, and FoundationOne Liquid CDx using circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and next-generation sequencing to detect tumor-specific mutations.

Figure 1. Clinical application of liquid biopsy (LB) in gastrointestinal cancer (GICs). Circulating tumor cells (CTCs), cell-free or circulating tumor DNA (cfDNA/ctDNA), tumor-educated platelets (TEP), exosomes, and RBCs in the blood of GICs patients can be used as potential biomarkers for LBs and their expression levels can be measured to determine the clinical status of GICs patients.

2. Overview of Different Methodologies and Their Current Clinical Application

2.1. Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs)

CTCs are tumor cells, shed from a primary tumor. They can enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system, potentially spreading into distant organs possibly leading to metastases [17][18]. Nevertheless, only a minority of CTCs become solid metastatic lesions because of a complex sequence of events needed, i.e., the detachment from the primary tumor, migration through the circulating blood, immune escape, and survival. It remains unclear how the detachment process from the primary tumor tissue takes place. Evidence supports the involvement of epithelial to mesenchymal transition, by which transformed epithelial cells can acquire the ability to invade, resist apoptosis, and disseminate. This could be the main driver for the detachment of tumor cells from the primary tumor [19][20][21][22][23][24]. Other reports hypothesize that cells split into different clusters [25]. It is noteworthy that gastrointestinal cancers compared to breast cancer have lower numbers of CTCs in peripheral blood due to portal vein circulations and a steady ‘first-pass effect’ in the liver [26]. Therefore, portal vein blood might be a unique sample site to isolate CTCs from gastrointestinal cancers. It has already been shown that the number of enriched CTCs from portal vein blood is higher than in the systemic circulation [27][28]. Portal vein blood can be collected intraoperatively or even by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling [29].

In addition to the number of CTCs, the analysis of physical (size, density, and electric charge) and biological (cell surface expression) properties could play a crucial role in future clinical use [30].

2.2. Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA)

A group of French scientists detected cfDNA fragments in the circulating plasma of patients with autoimmune disorders in 1948 [31]. Later it became clear that the release of cfDNA is not restricted to autoimmune disorders, but was also found amongst others in pregnant women [32], septic patients [33], people suffering from different types of cancers, and even in healthy individuals [34]. Numerous studies have been conducted to uncover the mechanisms by which DNA fragments are released from cells into the plasma or serum. Major mechanisms involve apoptosis, necrosis, phagocytosis, NETosis, or active secretion [35]. Basically, every cell and tissue type is able to release cfDNA into circulation. Consequently, based on cell and tissue-specific methylation patterns from comprehensive databases including the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) an assignment of cfDNA to different origins became possible [36]. Accordingly, the major source of cfDNA in blood results from hematopoietic cells, followed by vascular endothelial cells (up to 10%). However, cfDNA from liver tissue can also frequently be detected at low levels in circulation (up to 1%) in healthy people [36]. CtDNA is a fraction of cfDNA that originates from primary tumors, metastases, or from CTCs. Additionally, some findings are suggestive of an active release of ctDNA from living tumor cells involving exosomes [37]. CtDNA is characterized by small 70–200 base pair fragments circulating freely within the blood [31] showing a major fragment size of around 170 base pairs, which corresponds to nucleosomal fragments resulting from apoptosis [38]. The half-life of ctDNA is very short ranging from 15 min to 2.5 h before it is finally cleared by the liver and/or kidneys which is a prerequisite for a precise biomarker [39]. Concentrations of ctDNA in the blood of patients with a malignant tumor are significantly increased compared to healthy individuals [40]; however, levels of released ctDNA significantly vary between different tumor types and tumor stages. Furthermore, the match of cancer-specific alterations in the genome of solid tumors to those of ctDNA is a major discriminator between ctDNA and physiological cell-free DNA at steady state [41][42][43].

2.3. Circulating Extracellular Vesicles (Tumor Exosomes)

Exosomes are a subpopulation of extracellular vesicles (EVs), ranging in size from 30–150 nm. They are derived from the endosomal pathway via the formation of late endosomes or multivesicular bodies (MVBs). As an important mediator of intracellular communication, exosomes transmit various biological molecules including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids over distances within the protection of a lipidic bilayer-enclosed structure. Nearly all types of cells and all body fluids contain exosomes [44][45]. Cancer cells and other stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) also release exosomes and control tumor development through molecular exchanges mediated by exosomes [46][47]. Circulating extracellular vesicles (cEVs) are implied to be more stable in comparison to serological proteins as the lipidic bilayers defend the content from proteases and other enzymes [48].

2.4. Tumor-Educated Blood Platelets (TEPs)

Platelets play a central role in blood coagulation and in the healing of wounds, and their relationship with cancer has been extensively investigated [49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57]. There are two major studies that indicated the involvement of platelets during tumor progression. These studies contributed to the development of the concept of tumor-educated platelets (TEPs). The first study by Trousseau (1868) observed spontaneous coagulation being common in cancerous patients, stating that circulating platelets were affected by cancer [58]. The second study (Billroth T, 1877) described ‘’ thrombi filled with specific tumor elements’’ as part of metastasis, pointing out a direct interaction of cancer cells and platelets [59][60]. In recent years, several studies have focused on the impact of platelets during cancer progression, and some of them showed that platelet dysfunction and thrombotic disorders are important key factors in cancer development. By now it is well known that tumor-educated platelets (TEPs) are educated when they interact with the tumor cells in such a way as to lead to the detachment of biomolecules, such as proteins and RNA, tumor-specific splice events, and finally to megakaryocyte alteration [61]. Through this interaction, the RNA profile of blood platelets changes. This change has been used as an independent diagnostic marker for detecting TEPs in various solid tumors [62]. The RNA biomarkers of the directly transferred transcripts are EGFRvIII, PCA3, EML4-ALK, KRAS, EGFR, PIK3CA mutants, FOLH1, KLK2, KLK3, and NPY [63]. Here, the researchers describe the isolation, detection, and clinical relevance of TEPsin GICs.

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Estimated Number of New Cases and Deaths of Cancer in 2020. 2020. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Le, Q.; Wang, C.; Shi, Q. Meta-Analysis on the Improvement of Symptoms and Prognosis of Gastrointestinal Tumors Based on Medical Care and Exercise Intervention. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5407664.

- Chen, Z.-D.; Zhang, P.-F.; Xi, H.-Q.; Wei, B.; Chen, L.; Tang, Y. Recent Advances in the Diagnosis, Staging, Treatment, and Prognosis of Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Literature Review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 744839.

- Arnold, M.; Abnet, C.C.; Neale, R.E.; Vignat, J.; Giovannucci, E.L.; McGlynn, K.A.; Bray, F. Global Burden of 5 Major Types of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 335–349.e15.

- Saini, A.; Pershad, Y.; Albadawi, H.; Kuo, M.; Alzubaidi, S.; Naidu, S.; Knuttinen, M.-G.; Oklu, R. Liquid Biopsy in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Diagnostics 2018, 8, 75.

- Siravegna, G.; Marsoni, S.; Siena, S.; Bardelli, A. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 531–548.

- Niimi, K.; Ishibashi, R.; Mitsui, T.; Aikou, S.; Kodashima, S.; Yamashita, H.; Yamamichi, N.; Hirata, Y.; Fujishiro, M.; Seto, Y.; et al. Laparoscopic and endoscopic cooperative surgery for gastrointestinal tumor. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 187.

- Garraway, L.A.; Jänne, P.A. Circumventing Cancer Drug Resistance in the Era of Personalized Medicine. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 214–226.

- Goyal, L.; Saha, S.K.; Liu, L.Y.; Siravegna, G.; Leshchiner, I.; Ahronian, L.G.; Lennerz, J.K.; Vu, P.; Deshpande, V.; Kambadakone, A.; et al. Polyclonal Secondary FGFR2 Mutations Drive Acquired Resistance to FGFR Inhibition in Patients with FGFR2 Fusion–Positive Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 252–263.

- Russo, M.; Siravegna, G.; Blaszkowsky, L.S.; Corti, G.; Crisafulli, G.; Ahronian, L.G.; Mussolin, B.; Kwak, E.L.; Buscarino, M.; Lazzari, L.; et al. Tumor Heterogeneity and Lesion-Specific Response to Targeted Therapy in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 147–153.

- Gerlinger, M.; Rowan, A.J.; Horswell, S.; Math, M.; Larkin, J.; Endesfelder, D.; Gronroos, E.; Martinez, P.; Matthews, N.; Stewart, A.; et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 883–892.

- Hazar-Rethinam, M.; Kleyman, M.; Han, G.C.; Liu, D.; Ahronian, L.G.; Shahzade, H.A.; Chen, L.; Parikh, A.R.; Allen, J.N.; Clark, J.W.; et al. Convergent Therapeutic Strategies to Overcome the Heterogeneity of Acquired Resistance in BRAF(V600E) Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 417–427.

- Morelli, M.; Overman, M.; Dasari, A.; Kazmi, S.; Mazard, T.; Vilar, E.; Morris, V.; Lee, M.; Herron, D.; Eng, C.; et al. Characterizing the patterns of clonal selection in circulating tumor DNA from patients with colorectal cancer refractory to anti-EGFR treatment. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 731–736.

- Emoto, S.; Ishigami, H.; Yamashita, H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Kaisaki, S.; Kitayama, J. Clinical significance of CA125 and CA72-4 in gastric cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Gastric Cancer 2011, 15, 154–161.

- Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lu, M.; Shen, L. Predictive value of serum CEA, CA19-9 and CA72.4 in early diagnosis of recurrence after radical resection of gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 2011, 58, 2166–2170.

- Shimada, H.; Noie, T.; Ohashi, M.; Oba, K.; Takahashi, Y. Clinical significance of serum tumor markers for gastric cancer: A systematic review of literature by the Task Force of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Gastric Cancer 2013, 17, 26–33.

- Williams, S.C. Circulating tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4861.

- Nel, I.; David, P.; Gerken, G.G.H.; Schlaak, J.F.; Hoffmann, A.-C. Role of circulating tumor cells and cancer stem cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Int. 2014, 8, 321–329.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Klymkowsky, M.W.; Savagner, P. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: A cancer researcher’s conceptual friend and foe. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 174, 1588–1593.

- Polyak, K.; Weinberg, R.A. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: Acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 265–273.

- Thiery, J.P.; Acloque, H.; Huang, R.Y.J.; Nieto, M.A. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transitions in Development and Disease. Cell 2009, 139, 871–890.

- Yilmaz, M.; Christofori, G. EMT, the cytoskeleton, and cancer cell invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009, 28, 15–33.

- Barrallo-Gimeno, A.; Nieto, M.A. The Snail genes as inducers of cell movement and survival: Implications in development and cancer. Development 2005, 132, 3151–3161.

- Allard, W.J.; Matera, J.; Miller, M.C.; Repollet, M.; Connelly, M.C.; Rao, C.; Tibbe, A.G.J.; Uhr, J.W.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M. Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 6897–6904.

- Denève, E.; Riethdorf, S.; Ramos, J.; Nocca, D.; Coffy, A.; Daurès, J.-P.; Maudelonde, T.; Fabre, J.-M.; Pantel, K.; Alix-Panabières, C. Capture of Viable Circulating Tumor Cells in the Liver of Colorectal Cancer Patients. Clin. Chem. 2013, 59, 1384–1392.

- Tien, Y.W.; Kuo, H.C.; Ho, B.I.; Chang, M.C.; Chang, Y.T.; Cheng, M.F.; Chen, H.-L.; Liang, T.-Y.; Wang, C.-F.; Huang, C.-Y.; et al. A High Circulating Tumor Cell Count in Portal Vein Predicts Liver Metastasis from Periampullary or Pancreatic Cancer: A High Portal Venous CTC Count Predicts Liver Metastases. Medicine 2016, 95, e3407.

- Bissolati, M.; Sandri, M.T.; Burtulo, G.; Zorzino, L.; Balzano, G.; Braga, M. Portal vein-circulating tumor cells predict liver metastases in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer. Tumor Biol. 2014, 36, 991–996.

- Chapman, C.G.; Waxman, I. EUS-Guided Portal Venous Sampling of Circulating Tumor Cells. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2019, 21, 68.

- Alix-Panabières, C.; Pantel, K. Circulating tumor cells: Liquid biopsy of cancer. Clin. Chem. 2013, 59, 110–118.

- Mandel, P.; Metais, P. Nuclear Acids in Human Blood Plasma. Comptes Rendus Seances Soc. Biol. Ses Fil. 1948, 142, 241–243.

- Lo, Y.M.; Lau, T.K.; Zhang, J.; Leung, T.N.; Chang, A.M.; Hjelm, N.M.; Elmes, R.S.; Bianchi, D.W. Increased fetal DNA concentrations in the plasma of pregnant women carrying fetuses with trisomy 21. Clin. Chem. 1999, 45, 1747–1751.

- Grumaz, S.; Stevens, P.; Grumaz, C.; Decker, S.O.; Weigand, M.A.; Hofer, S.; Brenner, T.; von Haeseler, A.; Sohn, K. Next-generation sequencing diagnostics of bacteremia in septic patients. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 73.

- van der Pol, Y.; Mouliere, F. Toward the Early Detection of Cancer by Decoding the Epigenetic and Environmental Fingerprints of Cell-Free DNA. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 350–368.

- Aucamp, J.; Bronkhorst, A.J.; Badenhorst, C.P.S.; Pretorius, P.J. The diverse origins of circulating cell-free DNA in the human body: A critical re-evaluation of the literature. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 1649–1683.

- Moss, J.; Magenheim, J.; Neiman, D.; Zemmour, H.; Loyfer, N.; Korach, A.; Samet, Y.; Maoz, M.; Druid, H.; Arner, P.; et al. Comprehensive human cell-type methylation atlas reveals origins of circulating cell-free DNA in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5068.

- Kahlert, C.; Melo, S.; Protopopov, A.; Tang, J.; Seth, S.; Koch, M.; Zhang, J.; Weitz, J.; Chin, L.; Futreal, A.; et al. Identification of Double-stranded Genomic DNA Spanning All Chromosomes with Mutated KRAS and p53 DNA in the Serum Exosomes of Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 3869–3875.

- Nagata, S. Apoptotic DNA fragmentation. Exp. Cell Res. 2000, 256, 12–18.

- Fleischhacker, M.; Schmidt, B. Circulating nucleic acids (CNAs) and cancer—A survey. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Cancer 2007, 1775, 181–232.

- Leon, S.A.; Shapiro, B.; Sklaroff, D.M.; Yaros, M.J. Free DNA in the serum of cancer patients and the effect of therapy. Cancer Res. 1977, 37, 646–650.

- Lyberopoulou, A.; Aravantinos, G.; Efstathopoulos, E.P.; Nikiteas, N.; Bouziotis, P.; Isaakidou, A.; Papalois, A.; Marinos, E.; Gazouli, M. Mutational Analysis of Circulating Tumor Cells from Colorectal Cancer Patients and Correlation with Primary Tumor Tissue. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123902.

- Kinugasa, H.; Nouso, K.; Miyahara, K.; Morimoto, Y.; Dohi, C.; Tsutsumi, K.; Kato, H.; Okada, H.; Yamamoto, K. Detection of K-ras gene mutation by liquid biopsy in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer 2015, 121, 2271–2280.

- Lebofsky, R.; Decraene, C.; Bernard, V.; Kamal, M.; Blin, A.; Leroy, Q.; Frio, T.R.; Pierron, G.; Callens, C.; Bieche, I.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA as a non-invasive substitute to metastasis biopsy for tumor genotyping and personalized medicine in a prospective trial across all tumor types. Mol. Oncol. 2014, 9, 783–790.

- Théry, C. Exosomes: Secreted vesicles and intercellular communications. F1000 Biol. Rep. 2011, 3, 15.

- Cheng, L.; Sharples, R.A.; Scicluna, B.J.; Hill, A.F. Exosomes provide a protective and enriched source of miRNA for biomarker profiling compared to intracellular and cell-free blood. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 23743.

- Rak, J. Microparticles in Cancer. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2010, 36, 888–906.

- Hood, J.L.; San, R.S.; Wickline, S.A. Exosomes Released by Melanoma Cells Prepare Sentinel Lymph Nodes for Tumor Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 3792–3801.

- Li, A.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z. Exosomal proteins as potential markers of tumor diagnosis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 175.

- Franco, A.T.; Corken, A.; Ware, J. Platelets at the interface of thrombosis, inflammation, and cancer. Blood 2015, 126, 582–588.

- Lambert, A.W.; Pattabiraman, D.R.; Weinberg, R.A. Emerging Biological Principles of Metastasis. Cell 2017, 168, 670–691.

- Menter, D.G.; Kopetz, S.; Hawk, E.; Sood, A.K.; Loree, J.M.; Gresele, P.; Honn, K.V. Platelet "first responders" in wound response, cancer, and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017, 36, 199–213.

- Naderi-Meshkin, H.; Ahmadiankia, N. Cancer metastasis versus stem cell homing: Role of platelets. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 9167–9178.

- Haemmerle, M.; Stone, R.L.; Menter, D.G.; Afshar-Kharghan, V.; Sood, A.K. The Platelet Lifeline to Cancer: Challenges and Opportunities. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 965–983.

- Olsson, A.; Cedervall, J. The pro-inflammatory role of platelets in cancer. Platelets 2018, 29, 569–573.

- Xu, X.R.; Yousef, G.M.; Ni, H. Cancer and platelet crosstalk: Opportunities and challenges for aspirin and other antiplatelet agents. Blood 2018, 131, 1777–1789.

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhu, Q.; Zhan, P.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, J.; Lv, T.; Yong, S. Patterns and functional implications of platelets upon tumor "education". Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2017, 90, 68–80.

- Mancuso, M.E.; Santagostino, E. Platelets: Much more than bricks in a breached wall. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 178, 209–219.

- Hisada, Y.; Mackman, N. Cancer-associated pathways and biomarkers of venous thrombosis. Blood 2017, 130, 1499–1506.

- Kanikarla-Marie, P.; Lam, M.; Menter, D.G.; Kopetz, S. Platelets, circulating tumor cells, and the circulome. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017, 36, 235–248.

- Leblanc, R.; Peyruchaud, O. Metastasis: New functional implications of platelets and megakaryocytes. Blood 2016, 128, 24–31.

- Kuznetsov, H.S.; Marsh, T.; Markens, B.A.; Castaño, Z.; Greene-Colozzi, A.; Hay, S.A.; Brown, V.E.; Richardson, A.L.; Signoretti, S.; Battinelli, E.M.; et al. Identification of Luminal Breast Cancers That Establish a Tumor-Supportive Macroenvironment Defined by Proangiogenic Platelets and Bone Marrow–Derived Cells. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 1150–1165.

- Best, M.G.; Sol, N.; Kooi, I.E.; Tannous, J.; Westerman, B.A.; Rustenburg, F.; Schellen, P.; Verschueren, H.; Post, E.; Koster, J.; et al. RNA-Seq of Tumor-Educated Platelets Enables Blood-Based Pan-Cancer, Multiclass, and Molecular Pathway Cancer Diagnostics. Cancer Cell 2015, 28, 666–676.

- Tjon-Kon-Fat, L.-A.; Lundholm, M.; Schröder, M.; Wurdinger, T.; Thellenberg-Karlsson, C.; Widmark, A.; Wikström, P.; Nilsson, R.J.A. Platelets harbor prostate cancer biomarkers and the ability to predict therapeutic response to abiraterone in castration resistant patients. Prostate 2017, 78, 48–53.

More

Information

Subjects:

Medicine, Research & Experimental

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

630

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

18 Apr 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No