| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kobun Rovina | -- | 5366 | 2023-04-13 13:55:20 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 5366 | 2023-04-14 03:15:35 | | |

Video Upload Options

The food production industry generates millions of tonnes of waste every day, making it a major contributor to global waste production. Given the growing public concern about this issue, there has been a focus on utilizing the waste generated from popular fruits and vegetables, which contain high-added-value compounds. By efficiently using food waste from the fruit and vegetable industries, we can promote sustainable consumption and production practices that align with the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

1. Introduction

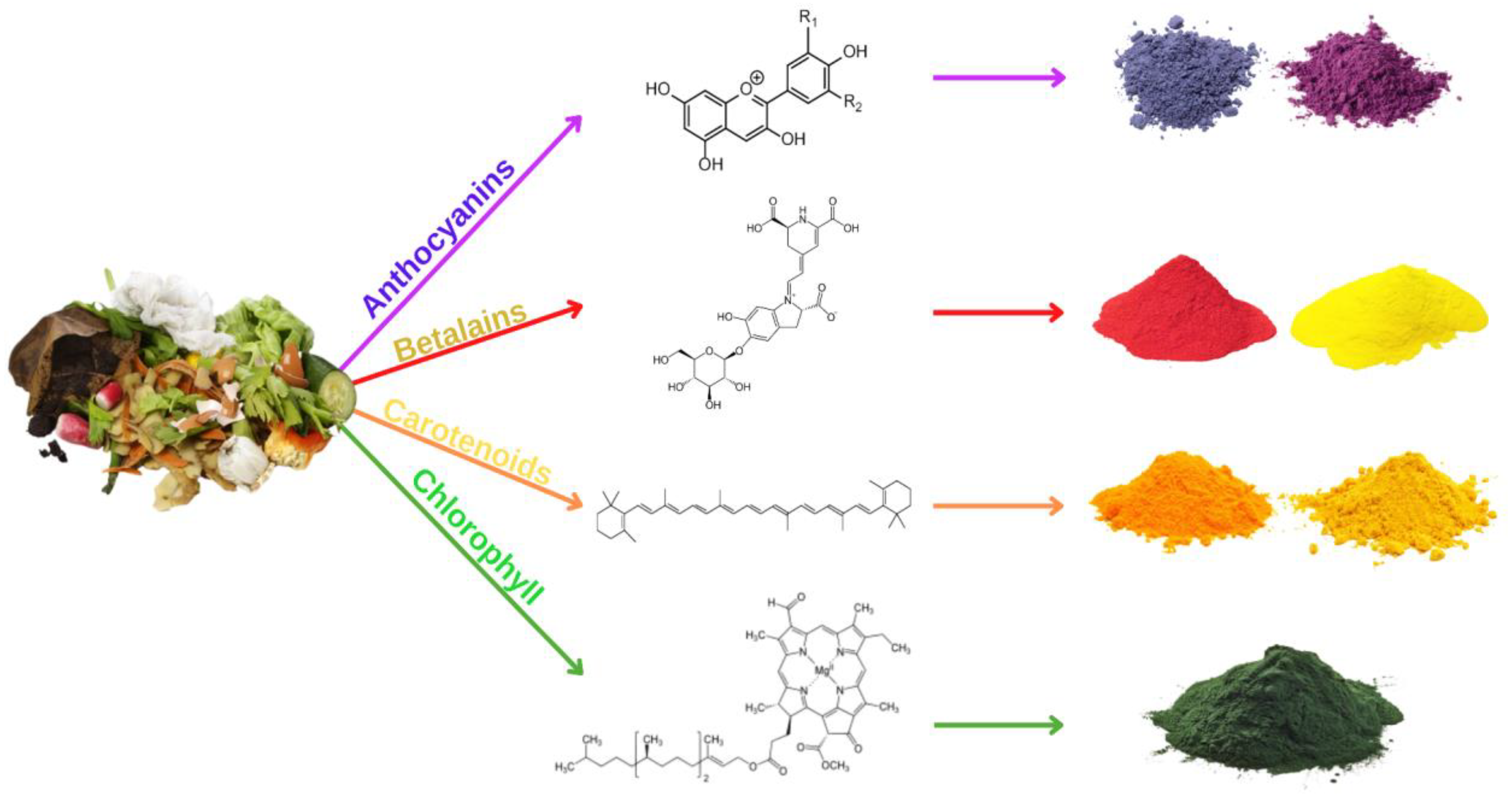

2. Bioactive Components in Fruits and Vegetables Waste

|

Fruits and Vegetable Waste |

Bioactive Compounds |

Extraction Method |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Fruits waste |

|||

|

Blackberry pomace |

Phenolic acids, anthocyanins |

Pressurized liquid extraction (PLE), supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) |

[23] |

|

Blueberry (Vaccinium ashei) juice |

Hot water bath and steam pretreatments |

[24] |

|

|

Blackberry, blueberry and jaboticaba skin |

- |

[25] |

|

|

Apple peels |

- |

[26] |

|

|

Strawberry fruit peel |

- |

[27] |

|

|

Raspberry pomace |

Solid phase extraction (SPE) |

[28] |

|

|

Red dragon fruit peels |

Methanol extraction |

[29] |

|

|

Tomato skin |

Carotenoids, phenolic acids, and flavonoids |

Supercritical CO2 extraction (SC-CO2) |

[30] |

|

Pumpkin seeds, peel, flesh |

Aqueous phase extraction |

[31] |

|

|

Papaya peel |

Ultrasound assisted extraction (UAE) |

[32] |

|

|

Melon peel |

- |

[33] |

|

|

Red beetroot peel extract |

Phenolic acids, flavonoids, betalains |

Maceration technique |

[34] |

|

Red beetroot juice |

Ultrasound assisted extraction (UAE) |

[35] |

|

|

Pulp and peel of prickly pear (Opuntia ficus-indica L. Mill) tissues |

Single extraction |

[36] |

|

|

Blueberry pomace extract |

Phenolic acids, anthocyanins, flavonol |

High voltage electrical discharges (HVED), pulsed electric field (PEF), ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) |

[37] |

|

Apple peels |

Phenolic, flavonoids |

- |

[38] |

|

Vegetable by-products |

|||

|

Broccoli and artichokes waste |

Phenolic, flavonoids |

Methanolic extraction |

[39] |

|

Broccoli waste (stalk) |

- |

[40] |

|

|

Asparagus leaf waste |

- |

[41] |

|

|

Asparagus Officinalis roots |

- |

[42] |

|

|

Onion skin |

Pressurized hot water extraction |

[43] |

|

|

Yellow onion skin |

Hot water extraction |

[44] |

|

|

Potato waste |

Maceration, hot water extraction |

[45] |

|

|

Artichoke, red pepper, carrot, and cucumber waste |

Ultrasonic processor |

[46] |

|

|

Potato peel |

Phenolic, flavonoids, anthocyanins, carotenoids |

- |

[47] |

|

Eggplant peel |

Phenolic, flavonoids, anthocyanins |

Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) |

[48] |

3. Extraction Methods

4. Valorization of Fruits and Vegetable Waste into Valuable Applications

4.1. Antioxidant

4.2. Antimicrobial

4.3. Antibrowning

4.4. Adsorbents

4.5. Indicator in Packaging

4.6. Enzymes

References

- UNICEF. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021; FAO Publisher: Rome, Italy, 2021.

- FAO, I. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; FAO Publisher: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 2–13.

- UNEP. Food Waste Index Report 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- FAO. Food Loss and Waste 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/capacity-development/food-loss-and-waste/en/ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- de los Ángeles Fernández, M.; Espino, M.; Gomez, F.J.; Silva, M.F. Novel approaches mediated by tailor-made green solvents for the extraction of phenolic compounds from agro-food industrial by-products. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 671–678.

- Amaya-Cruz, D.M.; Rodríguez-González, S.; Pérez-Ramírez, I.F.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Amaya-Llano, S.; Gallegos-Corona, M.A.; Reynoso-Camacho, R. Juice by-products as a source of dietary fibre and antioxidants and their effect on hepatic steatosis. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 17, 93–102.

- Bas-Bellver, C.; Barrera, C.; Betoret, N.; Seguí, L. Turning agri-food cooperative vegetable residues into functional powdered ingredients for the food industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1284.

- Ni, N.; Dumont, M.J. Protein-based hydrogels derived from industrial byproducts containing collagen, keratin, zein and soy. Waste Biomass Valorization 2017, 8, 285–300.

- Barros, H.D.; Baseggio, A.M.; Angolini, C.F.; Pastore, G.M.; Cazarin, C.B.; Marostica-Junior, M.R. Influence of different types of acids and pH in the recovery of bioactive compounds in Jabuticaba peel (Plinia cauliflora). Int. Food Res. J. 2019, 124, 16–26.

- Machado, A.P.D.; Rezende, C.A.; Rodrigues, R.A.; Barbero, G.F.; Rosa, P.D.V.E.; Martínez, J. Encapsulation of anthocyanin-rich extract from blackberry residues by spray-drying, freeze-drying and supercritical antisolvent. Powder Technol. 2018, 340, 553–562.

- Kurek, M.; Hlupić, L.; Garofulić, I.E.; Descours, E.; Ščetar, M.; Galić, K. Comparison of protective supports and antioxidative capacity of two bio-based films with revalorised fruit pomaces extracted from blueberry and red grape skin. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 20, 100315.

- Ardolino, F.; Parrillo, F.; Arena, U. Biowaste-to-biomethane or biowaste-to-energy? An LCA study on anaerobic digestion of organic waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 462–476.

- Gaikwad, K.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, Y.S. Development of polyvinyl alcohol and apple pomace bio-composite film with antioxidant properties for active food packaging application. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 1608–1619.

- Saberi, B.; Vuong, Q.V.; Chockchaisawasdee, S.; Golding, J.B.; Scarlett, C.J.; Stathopoulos, C.E. Physical, barrier, and antioxidant properties of pea starch-guar gum biocomposite edible films by incorporation of natural plant extracts. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 2240–2250.

- Šeregelj, V.; Pezo, L.; Šovljanski, O.; Lević, S.; Nedović, V.; Markov, S.; Tomić, A.; Čanadanović-Brunet, J.; Vulić, J.; Šaponjac, V.T.; et al. New concept of fortified yogurt formulation with encapsulated carrot waste extract. LWT 2021, 138, 110732.

- Ali, A.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Yu, L.; Baloch, Z.; Khalid, S.; Zhu, J.; Chen, L. Starch-based antimicrobial films functionalized by pomegranate peel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 129, 1120–1126.

- Maner, S.; Sharma, A.K.; Banerjee, K. Wheat flour replacement by wine grape pomace powder positively affects physical, functional and sensory properties of cookies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B 2017, 87, 109–113.

- Ayo, J.A.; Kajo, N. Effect of soybean hulls supplementation on the quality of acha based biscuits. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2016, 6, 49–56.

- Marchiani, R.; Bertolino, M.; Ghirardello, D.; McSweeney, P.L.; Zeppa, G. Physicochemical and nutritional qualities of grape pomace powder-fortified semi-hard cheeses. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 1585–1596.

- Coman, V.; Teleky, B.E.; Mitrea, L.; Martău, G.A.; Szabo, K.; Călinoiu, L.F.; Vodnar, D.C. Bioactive potential of fruit and vegetable wastes. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 91, 157–225.

- Gomes, S.; Finotelli, P.V.; Sardela, V.F.; Pereira, H.M.; Santelli, R.E.; Freire, A.S.; Torres, A.G. Microencapsulated Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) cake extract powder as an added-value functional food ingredient. LWT 2019, 116, 108495.

- Souza, A.C.P.; Gurak, P.D.; Marczak, L.D.F. Maltodextrin, pectin and soy protein isolate as carrier agents in the encapsulation of anthocyanins-rich extract from jaboticaba pomace. Food Bioprod. Process. 2017, 102, 186–194.

- Santos, P.H.; Ribeiro, D.H.B.; Micke, G.A.; Vitali, L.; Hense, H. Extraction of bioactive compounds from feijoa (Acca sellowiana (O. Berg) Burret) peel by low and high-pressure techniques. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2019, 145, 219–227.

- Zhang, L.; Wu, G.; Wang, W.; Yue, J.; Yue, P.; Gao, X. Anthocyanin profile, color and antioxidant activity of blueberry (Vaccinium ashei) juice as affected by thermal pretreatment. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 1035–1046.

- Rigolon, T.C.B.; Barros, F.A.R.D.; Vieira, É.N.R.; Stringheta, P.C. Prediction of total phenolics, anthocyanins and antioxidant capacity of blackberry (Rubus sp.), blueberry (Vaccinium sp.) and jaboticaba (Plinia cauliflora (Mart.) Kausel) skin using colorimetric parameters. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 40, 620–625.

- Riaz, A.; Aadil, R.M.; Amoussa, A.M.O.; Bashari, M.; Abid, M.; Hashim, M.M. Application of chitosan-based apple peel polyphenols edible coating on the preservation of strawberry (Fragaria ananassa cv Hongyan) fruit. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15018.

- Sirijan, M.; Pipattanawong, N.; Saeng-on, B.; Chaiprasart, P. Anthocyanin content, bioactive compounds and physico-chemical characteristics of potential new strawberry cultivars rich in-anthocyanins. J. Berry Res. 2020, 10, 397–410.

- Szymanowska, U.; Baraniak, B. Antioxidant and potentially anti-inflammatory activity of anthocyanin fractions from pomace obtained from enzymatically treated raspberries. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 299.

- Prabowo, I.; Utomo, E.P.; Nurfaizy, A.; Widodo, A.; Widjajanto, E.; Rahadju, P. Characteristics and antioxidant activities of anthocyanin fraction in red dragon fruit peels (Hylocereus polyrhizus) extract. Drug Invent. Today 2019, 12, 670–678.

- Pellicanò, T.M.; Sicari, V.; Loizzo, M.R.; Leporini, M.; Falco, T.; Poiana, M. Optimizing the supercritical fluid extraction process of bioactive compounds from processed tomato skin by-products. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 40, 692–697.

- Hussain, A.; Kausar, T.; Din, A.; Murtaza, M.A.; Jamil, M.A.; Noreen, S.; Rehman, H.U.; Shabbir, H.; Ramzan, M.A. Determination of total phenolic, flavonoid, carotenoid, and mineral contents in peel, flesh, and seeds of pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15542.

- Singla, M.; Singh, A.; Sit, N. Effect of microwave and enzymatic pretreatment and type of solvent on kinetics of ultrasound assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from ripe papaya peel. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 42, e14119.

- Gómez-García, R.; Campos, D.A.; Oliveira, A.; Aguilar, C.N.; Madureira, A.R.; Pintado, M. A chemical valorisation of melon peels towards functional food ingredients: Bioactives profile and antioxidant properties. Food Chem. 2021, 335, 127579.

- El-Beltagi, H.S.; El-Mogy, M.M.; Parmar, A.; Mansour, A.T.; Shalaby, T.A.; Ali, M.R. Phytochemical characterization and utilization of dried red beetroot (Beta vulgaris) peel extract in maintaining the quality of Nile Tilapia fish fillet. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 906.

- Fernando, G.S.N.; Wood, K.; Papaioannou, E.H.; Marshall, L.J.; Sergeeva, N.N.; Boesch, C. Application of an ultrasound-assisted extraction method to recover betalains and polyphenols from red beetroot waste. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 8736–8747.

- García-Cayuela, T.; Gómez-Maqueo, A.; Guajardo-Flores, D.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Cano, M.P. Characterization and quantification of individual betalain and phenolic compounds in Mexican and Spanish prickly pear (Opuntia ficus-indica L. Mill) tissues: A comparative study. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 76, 1–13.

- Lončarić, A.; Celeiro, M.; Jozinović, A.; Jelinić, J.; Kovač, T.; Jokić, S.; Lores, M. Green extraction methods for extraction of polyphenolic compounds from blueberry pomace. Foods 2020, 9, 1521.

- Gulsunoglu, Z.; Purves, R.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F.; Kilic-Akyilmaz, M. Enhancement of phenolic antioxidants in industrial apple waste by fermentation with Aspergillus spp. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 25, 101562.

- Lucera, A.; Costa, C.; Marinelli, V.; Saccotelli, M.A.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Conte, A. Fruit and vegetable by-products to fortify spreadable cheese. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 61.

- Salas-Millán, J.Á.; Aznar, A.; Conesa, E.; Conesa-Bueno, A.; Aguayo, E. Functional food obtained from fermentation of broccoli by-products (stalk): Metagenomics profile and glucosinolate and phenolic compounds characterization by LC-ESI-QqQ-MS/MS. LWT 2022, 169, 113915.

- Chitrakar, B.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Bhandari, B. Valorization of asparagus-leaf by-product through nutritionally enriched chips to evaluate the effect of powder particle size on functional properties and rutin contents. Dry. Technol. 2022, 41, 34–45.

- Zhang, H.; Birch, J.; Yang, H.; Xie, C.; Kong, L.; Dias, G.; Bekhit, A.E.D. Effect of solvents on polyphenol recovery and antioxidant activity of isolates of Asparagus Officinalis roots from Chinese and New Zealand cultivars. Int. J. Food Sci. 2018, 53, 2369–2377.

- Sagar, N.A.; Pareek, S.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A. Quantification of flavonoids, total phenols and antioxidant properties of onion skin: A comparative study of fifteen Indian cultivars. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2423–2432.

- Milea, Ș.A.; Crăciunescu, O.; Râpeanu, G.; Oancea, A.; Enachi, E.; Bahrim, G.E.; Stănciuc, N. Multifunctional ingredient from aqueous flavonoidic extract of yellow onion skins with cytocompatibility and cell proliferation properties. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7243.

- Joly, N.; Souidi, K.; Depraetere, D.; Wils, D.; Martin, P. Potato by-products as a source of natural Chlorogenic acids and phenolic compounds: Extraction, characterization, and antioxidant capacity. Molecules 2020, 26, 177.

- Vaz, A.A.; Odriozola-Serrano, I.; Oms-Oliu, G.; Martín-Belloso, O. Physicochemical properties and bioaccessibility of phenolic compounds of dietary fibre concentrates from vegetable by-products. Foods 2022, 11, 2578.

- Makori, S.I.; Mu, T.H.; Sun, H.N. Profiling of polyphenols, flavonoids and anthocyanins in potato peel and flesh from four potato varieties. Potato Res. 2022, 65, 193–208.

- Doulabi, M.; Golmakani, M.T.; Ansari, S. Evaluation and optimization of microwave-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from eggplant peel by-product. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14853.

- Rodriguez Garcia, S.L.; Raghavan, V. Green extraction techniques from fruit and vegetable waste to obtain bioactive compounds—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 6446–6466.

- Goulas, V.; Hadjivasileiou, L.; Primikyri, A.; Michael, C.; Botsaris, G.; Tzakos, A.G.; Gerothanassis, I.P. Valorization of carob fruit residues for the preparation of novel bi-functional polyphenolic coating for food packaging applications. Molecules 2019, 24, 3162.

- Piechowiak, T.; Skóra, B.; Grzelak-Błaszczyk, K.; Sójka, M. Extraction of antioxidant compounds from blueberry fruit waste and evaluation of their in vitro biological activity in human keratinocytes (HaCaT). Food Anal. Methods 2021, 14, 2317–2327.

- Cadiz-Gurrea, M.D.L.L.; Pinto, D.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Rodrigues, F. Olive fruit and leaf wastes as bioactive ingredients for cosmetics—A preliminary study. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 245.

- Rangaraj, V.M.; Rambabu, K.; Banat, F.; Mittal, V. Effect of date fruit waste extract as an antioxidant additive on the properties of active gelatin films. Food Chem. 2021, 355, 129631.

- Venturi, F.; Bartolini, S.; Sanmartin, C.; Orlando, M.; Taglieri, I.; Macaluso, M.; Lucchesini, M.; Trivellini, A.; Zinnia, A.; Mensuali, A. Potato peels as a source of novel green extracts suitable as antioxidant additives for fresh-cut fruits. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2431.

- Kurek, M.; Benbettaieb, N.; Ščetar, M.; Chaudy, E.; Repajić, M.; Klepac, D.; Valić, S.; Debeaufort, F. Characterization of food packaging films with blackcurrant fruit waste as a source of antioxidant and color sensing intelligent material. Molecules 2021, 26, 2569.

- Kam, W.Y.J.; Mirhosseini, H.; Abas, F.; Hussain, N.; Hedayatnia, S.; Chong, H.L.F. Antioxidant activity enhancement of biodegradable film as active packaging utilizing crude extract from durian leaf waste. Food Control 2018, 90, 66–72.

- Deshmukh, R.K.; Akhila, K.; Ramakanth, D.; Gaikwad, K.K. Guar gum/carboxymethyl cellulose based antioxidant film incorporated with halloysite nanotubes and litchi shell waste extract for active packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 201, 1–13.

- Orqueda, M.E.; Méndez, D.A.; Martínez-Abad, A.; Zampini, C.; Torres, S.; Isla, M.I.; López-Rubio, A.; Fabra, M.J. Feasibility of active biobased films produced using red chilto wastes to improve the protection of fresh salmon fillets via a circular economy approach. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 133, 107888.

- Ribeiro, A.C.B.; Cunha, A.P.; da Silva, L.M.R.; Mattos, A.L.A.; de Brito, E.S.; de Souza, M.D.S.M.; de Azeredo, H.M.C.; Ricardo, N.M.P.S. From mango by-product to food packaging: Pectin-phenolic antioxidant films from mango peels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 1138–1150.

- Merino, D.; Bertolacci, L.; Paul, U.C.; Simonutti, R.; Athanassiou, A. Avocado peels and seeds: Processing strategies for the development of highly antioxidant bioplastic films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 38688–38699.

- Arrieta, M.P.; Garrido, L.; Faba, S.; Guarda, A.; Galotto, M.J.; López de Dicastillo, C. Cucumis metuliferus fruit extract loaded acetate cellulose coatings for antioxidant active packaging. Polymers 2020, 12, 1248.

- Matta, E.; Tavera-Quiroz, M.J.; Bertola, N. Active edible films of methylcellulose with extracts of green apple (Granny Smith) skin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 124, 1292–1298.

- Han, H.S.; Song, K.B. Antioxidant activities of mandarin (Citrus unshiu) peel pectin films containing sage (Salvia officinalis) leaf extract. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 55, 3173–3181.

- Shahbazi, Y. The properties of chitosan and gelatin films incorporated with ethanolic red grape seed extract and Ziziphora clinopodioides essential oil as biodegradable materials for active food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 99, 746–753.

- Adilah, A.N.; Jamilah, B.; Noranizan, M.A.; Hanani, Z.N. Utilization of mango peel extracts on the biodegradable films for active packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 16, 1–7.

- Melo, P.E.; Silva, A.P.M.; Marques, F.P.; Ribeiro, P.R.; Brito, E.S.; Lima, J.R.; Azeredo, H.M. Antioxidant films from mango kernel components. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 95, 487–495.

- Moghadam, M.; Salami, M.; Mohammadian, M.; Khodadadi, M.; Emam-Djomeh, Z. Development of antioxidant edible films based on mung bean protein enriched with pomegranate peel. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 104, 105735.

- Rodsamran, P.; Sothornvit, R. Preparation and characterization of pectin fraction from pineapple peel as a natural plasticizer and material for biopolymer film. Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 118, 198–206.

- Vargas-Torrico, M.F.; Aguilar-Méndez, M.A.; von Borries-Medrano, E. Development of gelatin/carboxymethylcellulose active films containing Hass avocado peel extract and their application as a packaging for the preservation of berries. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 206, 1012–1025.

- Talón, E.; Trifkovic, K.T.; Nedovic, V.A.; Bugarski, B.M.; Vargas, M.; Chiralt, A.; González-Martínez, C. Antioxidant edible films based on chitosan and starch containing polyphenols from thyme extracts. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 1153–1161.

- Urbina, L.; Eceiza, A.; Gabilondo, N.; Corcuera, M.Á.; Retegi, A. Valorization of apple waste for active packaging: Multicomponent polyhydroxyalkanoate coated nanopapers with improved hydrophobicity and antioxidant capacity. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 21, 100356.

- Hanani, Z.N.; Yee, F.C.; Nor-Khaizura, M.A.R. Effect of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel powder on the antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of fish gelatin films as active packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 89, 253–259.

- Saleem, M.; Saeed, M.T. Potential application of waste fruit peels (orange, yellow lemon and banana) as wide range natural antimicrobial agent. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2020, 32, 805–810.

- Jodhani, K.A.; Nataraj, M. Synergistic effect of Aloe gel (Aloe vera L.) and Lemon (Citrus Limon L.) peel extract edible coating on shelf life and quality of banana (Musa spp.). J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 2318–2328.

- Meydanju, N.; Pirsa, S.; Farzi, J. Biodegradable film based on lemon peel powder containing xanthan gum and TiO2–Ag nanoparticles: Investigation of physicochemical and antibacterial properties. Polym. Test. 2022, 106, 107445.

- Alparslan, Y.; Baygar, T. Effect of chitosan film coating combined with orange peel essential oil on the shelf life of deepwater pink shrimp. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 842–853.

- Agdar GhareAghaji, M.; Zomordi, S.; Gharekhani, M.; Hanifian, S. Effect of edible coating based on salep containing orange (Citrus sinensis) peel essential oil on shelf life of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fillets. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15737.

- Ramli, A.N.M.; Sukri, N.A.M.; Azelee, N.I.W.; Bhuyar, P. Exploration of antibacterial and antioxidative activity of seed/peel extracts of Southeast Asian fruit Durian (Durio zibethinus) for effective shelf-life enhancement of preserved meat. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15662.

- Mayeli, M.; Mehdizadeh, T.; Tajik, H.; Esmaeli, F.; Langroodi, A.M. Combined impacts of zein coating enriched with methanolic and ethanolic extracts of sour orange peel and vacuum packing on the shelf life of refrigerated rainbow trout. Flavour Fragr. J. 2019, 34, 460–470.

- Shukor, U.A.A.; Nordin, N.; Tawakkal, I.S.M.A.; Talib, R.A.; Othman, S.H. Utilization of jackfruit peel waste for the production of biodegradable and active antimicrobial packaging films. In Biopolymers and Biocomposites from Agro-Waste for Packaging Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2021; pp. 171–192.

- Thivya, P.; Bhosale, Y.K.; Anandakumar, S.; Hema, V.; Sinija, V.R. Development of active packaging film from sodium alginate/carboxymethyl cellulose containing shallot waste extracts for anti-browning of fresh-cut produce. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 188, 790–799.

- Tinello, F.; Mihaylova, D.; Lante, A. Valorization of onion extracts as anti-browning agents. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 3, 16–21.

- Liang, D.; Liu, L.; Qin, Z.; Li, G.; Ding, B.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z. Antioxidant and antityrosinase activity of extractable condensed tannins from durian shells with antibrowning effect in fresh-cut asparagus lettuce model. LWT 2022, 162, 113423.

- Jirasuteeruk, C.; Theerakulkait, C. Inhibitory effect of different varieties of mango peel extract on enzymatic browning in potato purée. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2020, 54, 217–222.

- Faiq, M.; Theerakulkait, C. Effect of papaya peel extract on browning inhibition in vegetable and fruit slices. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2018, 30, 57–61.

- Martínez-Hernández, G.B.; Castillejo, N.; Artés-Hernández, F. Effect of fresh–cut apples fortification with lycopene microspheres, revalorized from tomato by-products, during shelf life. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 156, 110925.

- Tinello, F.; Mihaylova, D.; Lante, A. Effect of dipping pre-treatment with unripe grape juice on dried “Golden Delicious” apple slices. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2018, 11, 2275–2285.

- Maia, L.S.; Duizit, L.D.; Pinhatio, F.R.; Mulinari, D.R. Valuation of banana peel waste for producing activated carbon via NaOH and pyrolysis for methylene blue removal. Carbon Lett. 2021, 31, 749–762.

- Zaini, H.M.; Roslan, J.; Saallah, S.; Munsu, E.; Sulaiman, N.S.; Pindi, W. Banana peels as a bioactive ingredient and its potential application in the food industry. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 92, 105054.

- Ramutshatsha-Makhwedzha, D.; Mbaya, R.; Mavhungu, M.L. Application of activated carbon banana peel coated with al2o3-chitosan for the adsorptive removal of lead and cadmium from wastewater. Materials 2022, 15, 860.

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.L.; Xie, T.; Cao, J. Activated carbon derived from waste tangerine seed for the high-performance adsorption of carbamate pesticides from water and plant. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 316, 123929.

- Gnanasekaran, L.; Priya, A.K.; Gracia, F. Orange peel extract influenced partial transformation of SnO2 to SnO in green 3D-ZnO/SnO2 system for chlorophenol degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127464.

- Aminu, A.; Oladepo, S.A. Fast orange peel-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and use as visual colorimetric sensor in the selective detection of mercury (II) ions. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 5477–5487.

- Hassan, S.S.; Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Abu-Dieyeh, M.; McKay, G. Novel bioadsorbents based on date pits for organophosphorus pesticide remediation from water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103593.

- Mohammad, S.G.; El-Sayed, M.M. Removal of imidacloprid pesticide using nanoporous activated carbons produced via pyrolysis of peach stone agricultural wastes. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2021, 208, 1069–1080.

- Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Sweleh, A.O. Optimizing textile dye removal by activated carbon prepared from olive stones. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2019, 16, 100488.

- Batool, S.; Shah, A.A.; Bakar, A.F.A.; Maah, M.J.; Bakar, N.K.A. Removal of organochlorine pesticides using zerovalent iron supported on biochar nanocomposite from Nephelium lappaceum (Rambutan) fruit peel waste. Chemosphere 2022, 289, 133011.

- Shakoor, S.; Nasar, A. Removal of methylene blue dye from artificially contaminated water using citrus limetta peel waste as a very low cost adsorbent. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 66, 154–163.

- Salama, A. New sustainable hybrid material as adsorbent for dye removal from aqueous solutions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 487, 348–353.

- Goksu, A.; Tanaydin, M.K. Adsorption of hazardous crystal violet dye by almond shells and determination of optimum process conditions by Taguchi method. Desalin. Water Treat. 2017, 88, 189–199.

- Sharma, K.; Mahato, N.; Cho, M.H.; Lee, Y.R. Converting citrus wastes into value-added products: Economic and environmentally friendly approaches. Nutrition 2017, 34, 29–46.

- Chapman, J.; Ismail, A.E.; Dinu, C.Z. Industrial applications of enzymes: Recent advances, techniques, and outlooks. Catalysts 2018, 8, 238.

- Lugani, Y.; Vemuluri, V.R. Extremophiles Diversity, Biotechnological Applications and Current Trends. In Extremophiles; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 1–30.

- Liu, X.; Kokare, C. Microbial enzymes of use in industry. In Biotechnology of Microbial Enzymes; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 267–298.

- Ravindran, R.; Jaiswal, A.K. Microbial enzyme production using lignocellulosic food industry wastes as feedstock: A review. Bioengineering 2016, 3, 30.

- Gómez-García, R.; Vilas-Boas, A.A.; Oliveira, A.; Amorim, M.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pastrana, L.; Pintado, M.M.; Campos, D.A. Impact of simulated human gastrointestinal digestion on the bioactive fraction of upcycled pineapple by-products. Foods 2022, 11, 126.

- Ramli, A.N.M.; Hamid, H.A.; Zulkifli, F.H.; Zamri, N.; Bhuyar, P.; Manas, N.H.A. Physicochemical properties and tenderness analysis of bovine meat using proteolytic enzymes extracted from pineapple (Ananas comosus) and jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) by-products. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15939.

- Hussain, N.; Weng, C.H.; Munawar, N. Effects of different concentrations of pineapple core extract and maceration process on free-range chicken meat quality. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2022, 34, 124–131.

- Singh, T.A.; Sarangi, P.K.; Singh, N.J. Tenderisation of meat by bromelain enzyme extracted from pineapple wastes. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. 2018, 7, 3256–3264.

- Rizqiati, H.; Nugraheni, A.; Susanti, S.; Fatmawati, L.; Nuryanto, N.; Arifan, F. Characteristic of isolated crude bromelain extract from cayenne pineapple crown in various drying temperature and its effect on meat texture. Food Res. 2021, 5, 72–79.

- Sarmah, N.; Revathi, D.; Sheelu, G.; Yamuna Rani, K.; Sridhar, S.; Mehtab, V.; Sumana, C. Recent advances on sources and industrial applications of lipases. Biotechnol. Prog. 2018, 34, 5–28.

- Okino-Delgado, C.H.; Pereira, M.S.; da Silva, J.V.I.; Kharfan, D.; do Prado, D.Z.; Fleuri, L.F. Lipases obtained from orange wastes: Commercialization potential and biochemical properties of different varieties and fractions. Biotechnol. Prog. 2019, 35, e2734.

- Tambun, R.; Tambun, J.A.; Tarigan, I.A.A. Fatty acid production from avocado seed by activating Lipase Enzyme in the seed. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 725, 12075.

- Shinde, A.; Kolhe, D.; Hase, D.P.; Chavan, M.J. A brief introduction about carica papaya linn. World J. Pharm. Res. 2020, 9.

- Adiaha, M.S. Effect of nutritional, medicinal and pharmacological properties of papaya (Carica papaya Linn.) to human development: A review. World Sci. News 2017, 2, 238–249.

- Phothiwicha, A.; Thamsaad, K.; Boontranurak, K.; Sintuya, P.; Panyoyai, N. Utilization of papain extracted from Chaya and papaya stalks as halal beef tenderiser. IFSTJ 2021, 5, 1–5.

- Kumar, D. A review of the use of microbial amylase in industry. Asian J. Res. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2021, 11, 57–61.

- Abdullah, T.; Nurhidayatullah, N.; Widiati, B. Seed waste of mango (Mangifera indica) as raw material glucose syrup alternative substitute for synthetic sweetener. J. Pijar Mipa 2022, 17, 271–275.

- Mushtaq, Q.; Irfan, M.; Tabssum, F.; Iqbal Qazi, J. Potato peels: A potential food waste for amylase production. J. Food Process Eng. 2017, 40, e12512.