Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Catalin Stefan Ghenea | -- | 1511 | 2023-03-26 20:51:14 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 1511 | 2023-03-27 07:59:17 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Negoita, L.M.; Ghenea, C.S.; Constantinescu, G.; Sandru, V.; Stan-Ilie, M.; Plotogea, O.; Shamim, U.; Dumbrava, B.F.; Mihaila, M. Endoscopic of the Upper Digestive Tract Management. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42543 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Negoita LM, Ghenea CS, Constantinescu G, Sandru V, Stan-Ilie M, Plotogea O, et al. Endoscopic of the Upper Digestive Tract Management. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42543. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Negoita, Livia Marieta, Catalin Stefan Ghenea, Gabriel Constantinescu, Vasile Sandru, Madalina Stan-Ilie, Oana-Mihaela Plotogea, Umar Shamim, Bogdan Florin Dumbrava, Mariana Mihaila. "Endoscopic of the Upper Digestive Tract Management" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42543 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Negoita, L.M., Ghenea, C.S., Constantinescu, G., Sandru, V., Stan-Ilie, M., Plotogea, O., Shamim, U., Dumbrava, B.F., & Mihaila, M. (2023, March 26). Endoscopic of the Upper Digestive Tract Management. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42543

Negoita, Livia Marieta, et al. "Endoscopic of the Upper Digestive Tract Management." Encyclopedia. Web. 26 March, 2023.

Copy Citation

The European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends immediate (<2 h, maximum 6 h after ingestion) therapeutic endoscopy for foreign bodies causing complete obstruction, sharp objects and batteries or magnets. Urgent endoscopy (<24 h) should also be performed for other esophageal foreign bodies without complete obstruction. Endoscopy of the upper digestive tract is very sensitive in detecting foreign bodies and has the advantage that therapeutic maneuvers can be performed. In addition, endoscopy may reveal pre-existing esophageal pathology leading to obstruction and any mucosal damage.

foreign bodies

food impaction

endoscopy

upper gastrointestinal tract

1. Introduction

Two of the most common endoscopic emergencies are esophageal food impaction (EFI) and foreign object ingestion (FOI) [1]. Most swallowed foreign bodies (80–90%) pass spontaneously, but endoscopic removal is required in about 10–20% of cases, and less than 1% require surgery to remove the foreign body or treat complications [2][3]. Depending on the type of foreign body swallowed, its location and the patient’s health status, there is a risk that the patient will quickly become unstable [4].

Endoscopy of the upper and lower digestive tract is the gold standard for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes for foreign bodies that have entered the gastrointestinal tract, with a failure rate of less than 5% of cases [5]. Foreign bodies cross the digestive tract and can cause obstruction or perforation; in addition, sharp objects at any point of impaction may cause perforation before extraction [6]. Esophageal perforation can be avoided when foreign bodies are pulled into the scope (overtube) before extraction [6][7]. The elective location of foreign bodies is at the level of the anatomical strictures of the esophagus; foreign bodies may also have a place at the level of congenital stenoses or post-caustic stenoses, as well as at the level of some regions with extrinsic compression [8].

2. Management

The European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends immediate (<2 h, maximum 6 h after ingestion) therapeutic endoscopy for foreign bodies causing complete obstruction, sharp objects and batteries or magnets [2]. Urgent endoscopy (<24 h) should also be performed for other esophageal foreign bodies without complete obstruction [2].

Endoscopy of the upper digestive tract is very sensitive in detecting foreign bodies and has the advantage that therapeutic maneuvers can be performed [9]. In addition, endoscopy may reveal pre-existing esophageal pathology leading to obstruction and any mucosal damage [10]. The timing of endoscopic intervention is based on the perceived risks of aspiration and perforation [2]. In most cases, conscious sedation is sufficient for the endoscopic procedure (low dose midazolam) [11]. However, in complex cases where endoscopy takes a long time, it is necessary to perform general anesthesia to ensure the comfort of the patient and the physician [12]. Cases with upper esophageal obstruction may require orotracheal intubation or the use of a supratube to avoid mucosal injury [13]. In patients who do not have signs of complete obstruction, endoscopy may be delayed because the spontaneous passage of the food bolus may occur [14][15]. However, endoscopic intervention should not be delayed for more than 24 h after presentation because of the increased risk of complications, and preferably should be performed within 12 h [12]. In patients with severe distress, who are unable to control secretions, the endoscopy should be performed in the first 6–12 h. The sooner the esophageal obstruction is removed, the less risk there is of injuring the mucosa [2][16].

The risk of complications decreases if the object has passed into the stomach. Therefore, observation is acceptable and endoscopic intervention may be unnecessary, except for sharp and pointed objects. Sharp objects should be immediately removed whenever their location is above the ligament of Treitz. Long objects (>5 cm) or wide objects (>2 cm) should be endoscopically removed from the stomach if they have not passed in 3–5 days.

It is important for the gastroenterologist to be well trained (minimum 2500 endoscopies performed) and to know the appropriate instruments and techniques according to each situation [5][17]. Gastroenterologists need to be familiar with and trained in a wide range of foreign body removal instruments [9]. A flexible endoscope is the gold standard diagnostic and therapeutic method for the obstruction of food and other foreign bodies, which has been successful in studies in over 90% of cases [18]. Standard flexible gastroscopes (9.8 mm outer diameter with a 2.8 mm diameter channel) are widely accepted and effective for adult patients [19]. The instruments used to extract foreign bodies from the digestive tract are varied and are used according to the type of foreign body: polypectomy snare, alligator forceps, Savary plug, tripod forceps, Dormia basket, recovery net, clear latex cap and overtube [20]. Recently, balloon enteroscopy (single and double) has been used to remove foreign bodies that cannot be removed with the standard flexible endoscope [4][21]. Grappling tongs with two to five teeth are used for lifting soft objects, but cannot be used for larger and hard foreign objects [2].

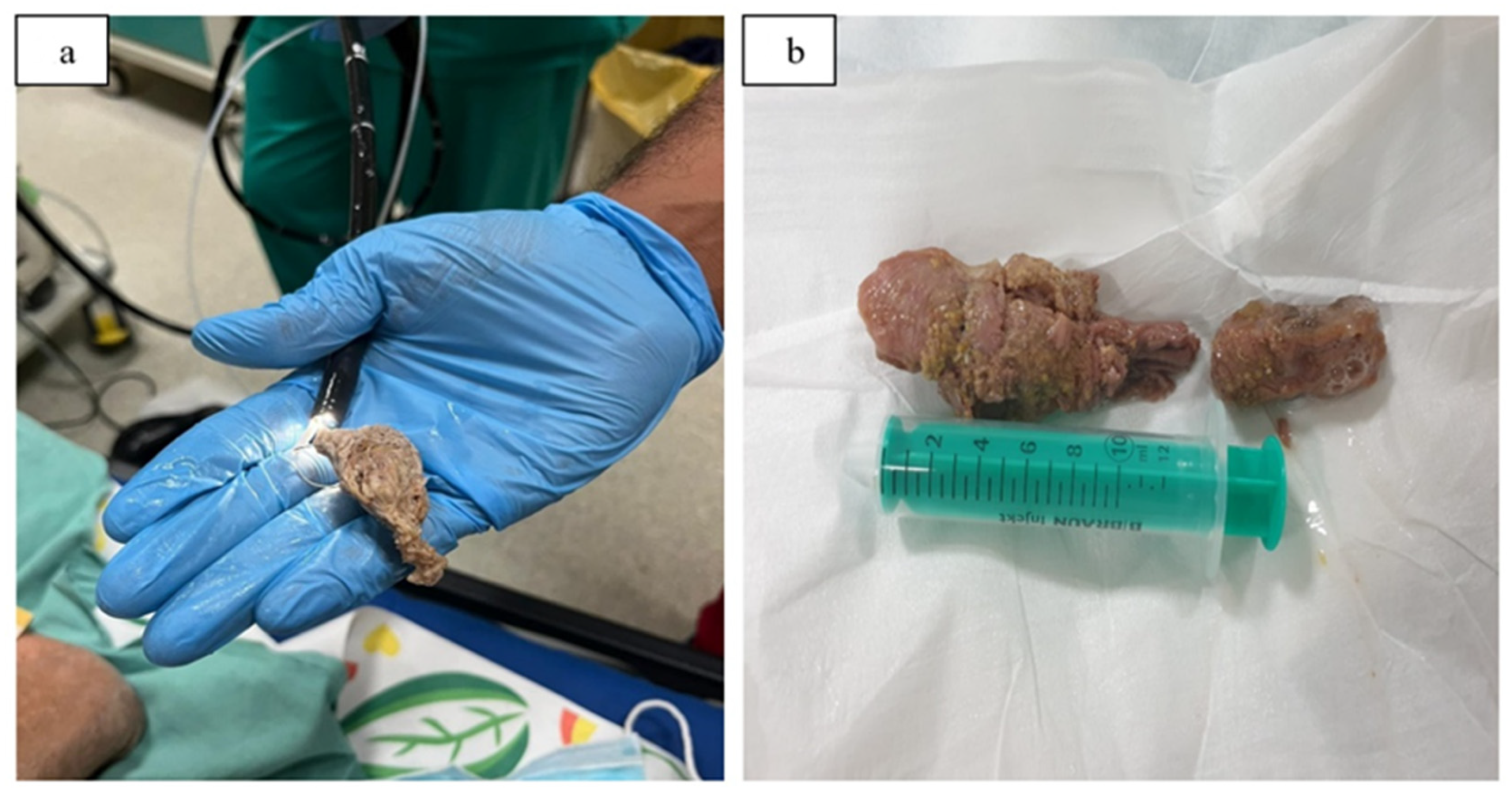

The Dormia basket is used to catch round objects, and nets or recovery bags are used for a more secure catch for some foreign bodies (coins, batteries) and the removal of food boluses; in addition, polypectomy traps are widely available and inexpensive [22]. Depending on the object to be removed, the endoscopist selects the type of instrument to use to extract the foreign body (Table 2) [2]. For small objects (needles, razor blades), alligator or rat forceps can be used; for soft objects, the endoscopist uses the Dormia basket, the polypectomy snare or the recovery net (Figure 1a,b) [23].

Figure 1. (a,b) Esophageal food impaction, extraction with polypectomy snares. From the Emergency Clinical Hospital Bucharest collection.

Table 2. Overview of retrieval devices, according to ESGE Clinical Guideline 2016 [2].

| Foreign Body | Endoscopic Retrieval Devices |

|---|---|

| Blunt bodies | Polypectomy snare, Dormia basket, retrieval net, grasping forceps |

| Cutting objects | Grasping forceps, polypectomy snare, Dormia basket, retrieval net, clear latex cap, overtube |

| Long objects | Polypectomy snare, Dormia basket |

| Impacted food (bolus) | Polypectomy snare, grasping forceps, retrieval forceps, Dormia basket |

A Foley urinary catheter has been used sporadically in children who have swallowed various objects [24]. When the foreign object is located in the stomach, to protect the esophageal mucosa, a overtube is used through which the object will be extracted [20].

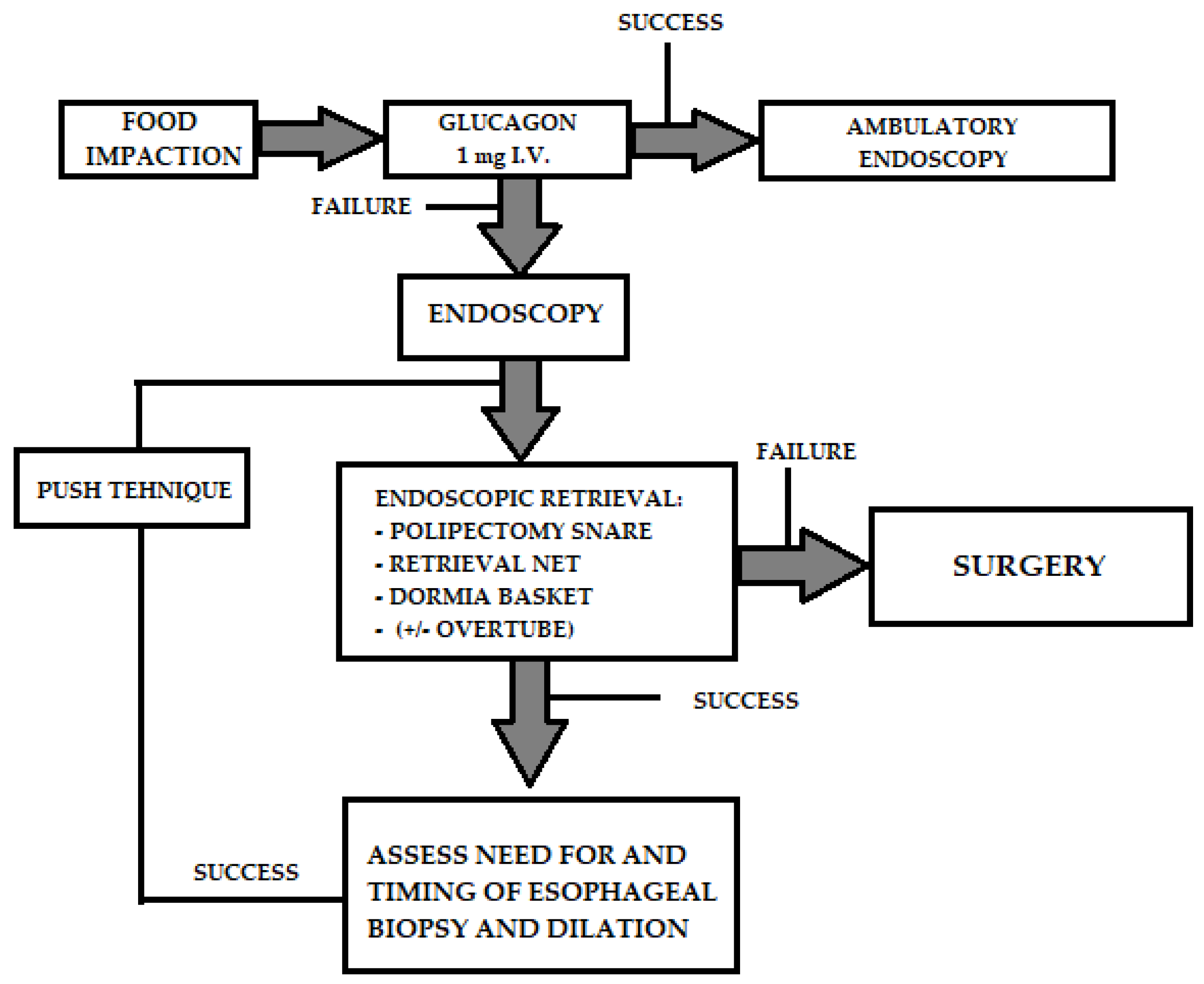

Several non-endoscopic therapeutic approaches have been investigated. Glucagon, administered in doses of 0.5–2.0 mg, can cause relaxation of the esophageal smooth muscle and lower esophageal sphincter, allowing the passage of the foreign body or food [25]. Most authors advocate administration of 1 mg glucagon before endoscopy (Chart 1), and if the foreign body does not advance, administration can be repeated after 30 min [26]. Successful therapy with glucagon ranges from 12% to 58%. Side effects of glucagon comprise nausea, vomiting and abdominal distension. Carbonated beverages such as Coca-Cola or Pepsi can be used to cleanse the esophagus with little risk to the patient [27]. These effervescent agents release carbon dioxide gas to distend the lumen and also to push the foreign body from the esophagus into the stomach. However, aspiration and perforation have been reported as possible complications. There are numerous diseases of the esophagus that favor obstruction (Table 3), such as peptic strictures, eosinophilic esophagitis or esophageal motility disorders (achalasia) or surgical interventions (Nissen fundoplication, esophagectomy, bariatric surgery) [4]. Although it is an underestimated condition, eosinophilic esophagitis is thought to be one of the main causes of food impaction. Mucosal biopsies should be obtained after bolus removal in order to establish diagnosis and therefore prevent reimpaction.

Chart 1. Therapeutic algorithm for food impaction in the esophagus. Glucagon can be administered intravenously before endoscopy to relax the esophagus and accelerate spontaneous mobilization of the impacted food. If this fails, endoscopy is performed and the foreign body is mobilized or extracted.

Table 3. Pathology of the esophagus that can cause the retention of foreign bodies, by Fung et al. [4].

| Examples of Underlying Disorders Implied in Esophageal Obstruction | |

|---|---|

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | Schatzki ring |

| Peptic stricture | Radiation-induced stricture |

| Esophageal neoplasia | Diverticulum |

| Achalasia and other spastic dysmotility | Post-surgical (fundoplication) |

Nifedipine and nitroglycerin are not recommended for esophageal obstruction due to side effects and lack of efficacy [28]. Radiological methods under fluoroscopy have been described for treatment, using Foley probes and suction probes to extract the objects [29]. The most frequently described device is the Foley catheter which is passed distal to the foreign object, inflated at the tip and then withdrawn into the oropharynx along with the object. The procedure is performed under fluoroscopic guidance. However, radiological methods are not commonly preferred, unless flexible endoscopy is unavailable, because the object cannot be controlled, especially at the hypopharynx and the pharyngoesophageal sphincter [29][30]. Complications may include aspiration, perforation, laryngeal spasm, epistaxis and even death of the patient [23]. The timing for endoscopy have been summarized in Table 4. To protect the airway, older guidelines and manuals often recommended anesthesia and orotracheal intubation [17]. In the experience of the Bucharest Emergency Hospital, orotracheal intubation to protect the airway is not necessary in most cases, and sedation can be easily provided with midazolam [17].

Table 4. Timing for endoscopy [2].

| Object Type | Location | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Batteries | Esophagus | Immediate (<2 h) |

| Stomach/small intestine | Urgent | |

| Magnets | Esophagus | Urgent |

| Stomach/small intestine | Urgent | |

| Cutting objects | Esophagus | Immediate (<2 h) |

| Stomach/small intestine | Urgent | |

| Blunt and small foreign body < 2.5 cm size | Esophagus | Urgent |

| Stomach/small intestine | Non-urgent | |

| Blunt and medium-sized foreign body > 2.5 cm size | Esophagus | Urgent |

| Stomach/small intestine | Non-urgent | |

| Large object > 5 cm | Esophagus | Urgent |

| Stomach/small intestine | Urgent | |

| Impacted food (bolus) | Esophagus | Immediate (urgent if obstruction is not complete) |

References

- Gurala, D.; Polavarapu, A.; Philipose, J.; Amarnath, S.; Avula, A.; Idiculla, P.S.; Demissie, S.; Gumaste, V. Esophageal Food Impaction: A Retrospective Chart Review. Gastroenterol. Res. 2021, 14, 173–178.

- Birk, M.; Bauerfeind, P.; Deprez, P.H.; Häfner, M.; Hartmann, D.; Hassan, C.; Hucl, T.; Lesur, G.; Aabakken, L.; Meining, A. Removal of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in adults: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy 2016, 48, 489–496.

- Storm, A.C.; Fishman, D.S.; Buxbaum, J.L.; Coelho-Prabhu, N.; Al-Haddad, M.A.; Amateau, S.K.; Calderwood, A.H.; DiMaio, C.J.; Elhanafi, S.E.; Forbes, N.; et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on informed consent for GI endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2022, 95, 207–215.e2.

- Fung, B.M.; Sweetser, S.; Song, L.M.W.K.; Tabibian, J.H. Foreign object ingestion and esophageal food impaction: An update and review on endoscopic management. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2019, 11, 174–192.

- Sugawa, C. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: A review. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2014, 6, 475–481.

- Patel, N.R.; Sharma, P. Foreign Bodies in Esophagus: An Experience with Rigid Esophagoscope in ENT Practice. Int. J. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 12, 1–5.

- Nimmo, S.S.; Nimmo, A.; Chin, G.A. Ingestion of a unilateral removable partial denture causing serious complications. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1988, 66, 24–26.

- Toader, C.; Oprea, A.; Ştefan, O.; Lupu, V.V.; Mircea Drăghici, M.T. Diagnosis and treatment of esophageal foregin bodies in children. Rom. Med. J. 2016, 63, 76–80.

- Ferrari, D.; Aiolfi, A.; Bonitta, G.; Riva, C.G.; Rausa, E.; Siboni, S.; Toti, F.; Bonavina, L. Flexible versus rigid endoscopy in the management of esophageal foreign body impaction: Systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2018, 13, 42.

- Ruan, W.S.; Li, Y.N.; Feng, M.X.; Lu, Y.Q. Retrospective observational analysis of esophageal foreign bodies: A novel characterization based on shape. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4273.

- Jun, J.; Han, J.I.; Choi, A.L.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, D.Y.; Lee, M. Adverse events of conscious sedation using midazolam for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Anesth. Pain Med. 2019, 14, 401–406.

- Eisen, G.M.; Baron, T.H.; Dominitz, J.A.; Faigel, D.O.; Goldstein, J.L.; Johanson, J.F.; Mallery, J.S.; Raddawi, H.M.; Vargo, J.J.; Waring, J.P.; et al. Guideline for the management of ingested foreign bodies. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2002, 55, 802–806.

- Spurling, T.J.; Zaloga, G.P.; Richter, J.E. Fiberendoscopic removal of a gastric foreign body with overtube technique. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1983, 29, 226–227.

- Webb, W.A. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: Update. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1995, 41, 39–51.

- Henderson, C.T.; Engel, J.; Schlesinger, P. Foreign body ingestion: Review and suggested guidelines for management. Endoscopy 1987, 19, 68–71.

- Ko, H.H.; Enns, R. Review of food bolus management. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 22, 805–808.

- Constantinescu, G.; Stan-Ilie, M.; Oprita, R. Gastroenterologie; II. Editura Niculescu: Bucharest, Romania, 2022; ISBN 978-606-38-0775-6.

- Ginsberg, G.G. Management of ingested foreign objects and food bolus impactions. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1995, 41, 33–38.

- Nagata, N.; Niikura, R.; Yamada, A.; Sakurai, T.; Shimbo, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Okamoto, M.; Mitsuno, Y.; Ogura, K.; Hirata, Y.; et al. Acute middle gastrointestinal bleeding risk associated with NSAIDs, antithrombotic drugs, and PPIs: A multicenter case-control study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151332.

- Tierney, W.M.; Adler, D.G.; Conway, J.D.; Diehl, D.L.; Farraye, F.A.; Kantsevoy, S.V.; Kaul, V.; Kethu, S.R.; Kwon, R.S.; Mamula, P.; et al. Overtube use in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2009, 70, 828–834.

- Yuki, T.; Ishihara, S.; Okada, M.; Kusunoki, R.; Moriyama, I.; Amano, Y.; Kinoshita, Y. Double-alloon endoscopy for treatment of small bowel penetration by fish bone. Dig. Endosc. 2012, 24, 281.

- Faigel, D.O.; Stotland, B.R.; Kochman, M.L.; Hoops, T.; Judge, T.; Kroser, J.; Lewis, J.; Long, W.B.; Metz, D.C.; O’Brien, C.; et al. Device choice and experience level in endoscopic foreign object retrieval: An in vivo study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1996, 43, 334.

- Magalhães-Costa, P.; Carvalho, L.; Rodrigues, J.P.; Túlio, M.A.; Marques, S.; Carmo, J.; Bispo, M.; Chagas, C. Endoscopic Management of Foreign Bodies in the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract: An Evidence-Based Review Article. GE Port. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 23, 142–152.

- Kelley, J.E.; Leech, M.H.; Carr, M.G. A safe and cost-effective protocol for the management of esophageal coins in children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1993, 28, 898–900.

- Alaradi, O.; Bartholomew, M.; Barkin, J.S.; Bolondi, L. Upper endoscopy and glucagon: A new technique in the management of acute esophageal food impaction. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 96, 912–913.

- Colon, V.; Grade, A.; Pulliam, G.; Johnson, C.; Fass, R. Effect of doses of glucagon used to treat food impaction on esophageal motor function of normal subjects. Dysphagia 1999, 14, 27–30.

- Karanjia, N.D.; Rees, M. The use of Coca-Cola in the management of bolus obstruction in benign oesophageal stricture. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 1993, 75, 94–95.

- Thimmapuram, J.; Oosterveen, S.; Grim, R. Use of Glucagon in Relieving Esophageal Food Bolus Impaction in the Era of Eosinophilic Esophageal Infiltration. Dysphagia 2013, 28, 212–216.

- Shaffer, H.A.; de Lange, E.E. Gastrointestinal foreign bodies and strictures: Radiologic interventions. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 1994, 23, 207–249.

- Schunk, J.E.; Harrison, A.M.; Corneli, H.M.; Nixon, G.W. Fluoroscopic foley catheter removal of esophageal foreign bodies in children: Experience with 415 episodes. Pediatrics 1994, 94, 709–714.

More

Information

Subjects:

Gastroenterology & Hepatology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Entry Collection:

Gastrointestinal Disease

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

27 Mar 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No