Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yinuo Wang | -- | 3167 | 2023-03-22 10:20:24 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | + 1 word(s) | 3168 | 2023-03-23 02:06:35 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Wang, Y.; Dobreva, G. Epigenetics in LMNA-Related Cardiomyopathy. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42422 (accessed on 06 March 2026).

Wang Y, Dobreva G. Epigenetics in LMNA-Related Cardiomyopathy. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42422. Accessed March 06, 2026.

Wang, Yinuo, Gergana Dobreva. "Epigenetics in LMNA-Related Cardiomyopathy" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42422 (accessed March 06, 2026).

Wang, Y., & Dobreva, G. (2023, March 22). Epigenetics in LMNA-Related Cardiomyopathy. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42422

Wang, Yinuo and Gergana Dobreva. "Epigenetics in LMNA-Related Cardiomyopathy." Encyclopedia. Web. 22 March, 2023.

Copy Citation

Mutations in the gene for lamin A/C (LMNA) cause a diverse range of diseases known as laminopathies. LMNA-related cardiomyopathy is a common inherited heart disease and is highly penetrant with a poor prognosis. Numerous investigations using mouse models, stem cell technologies, and patient samples have characterized the phenotypic diversity caused by specific LMNA variants and contributed to understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of heart disease. As a component of the nuclear envelope, LMNA regulates nuclear mechanostability and function, chromatin organization, and gene transcription.

nuclear lamina

lamin A/C

LMNA

cardiomyopathy

epigenetics

chromatin architecture

stem cells

1. Introduction

Mutations in genes encoding proteins of the nuclear lamina result in wide-ranging clinical phenotypes collectively referred to as laminopathies [1]. Many of these diseases are caused by mutations in the gene for lamin A/C (LMNA) and affect primarily the muscles, the peripheral nerves, and the adipose tissue or cause systemic diseases such as premature aging syndromes [2]. The LMNA gene encodes A-type lamins, generated by alternative splicing, of which lamins A and C are the main splicing products [3][4]. In addition to the A-type lamins, the nuclear lamina is composed of B-type lamins, i.e., lamins B1 and B2, encoded by LMNB1 and LMNB2 genes, respectively [5][6][7][8]. LMNB2 also encodes the germ-line-specific lamin B3, produced by alternative splicing [9].

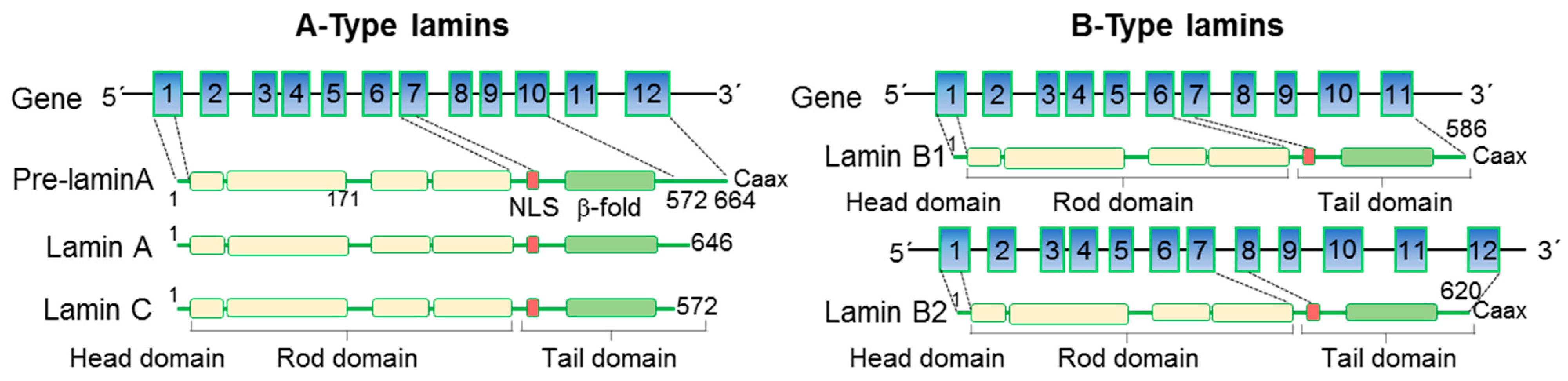

A- and B-type lamins have a common structural organization: a short “head” domain at the N-terminus followed by a central helical rod domain and a C-terminal “tail” domain. The central rod domain is composed of four coiled-coil regions that allow lamins to form parallel coiled-coil dimers and higher-order meshworks [10][11][12]. The “tail” consists of a globular region, which adopts an immunoglobulin (Ig)-like β-fold involved in protein–protein interactions. Pre-lamin A- and B-type lamins also have a CaaX motif at the C-terminus which guides protein farnesylation and carboxyl methylation, important for targeting to the nuclear envelope [10][11][12] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Structure of nuclear lamins. A- and B-type lamins have a conserved domain structure, consisting of a short N-terminal “head” domain, central helical coiled-coil rod domain, and a C-terminal immunoglobulin (Ig)-like β-fold domain. The nuclear localization signal (NLS) is located at the beginning of the tail domain. Pre-lamin A- and B-type lamins also have a CaaX motif at the C-terminus guiding their targeting to the inner nuclear membrane.

Both A- and B-type lamins form separate but interconnected filamentous meshworks located between the inner nuclear membrane and the peripheral heterochromatin, which on the one hand provide structural support to the nucleus and on the other hand anchor chromatin at the nuclear periphery, thereby shaping the higher-order chromatin structure [13][14][15]. In contrast to lamins B1 and B2, which are localized at the periphery and associate mainly with transcriptionally inactive chromatin [16][17], lamins A and C are also found in the nuclear interior and associate with both heterochromatin and euchromatin [18]. In addition, lamins interact with the LINC complex, which couples the nucleoskeleton with the cytoskeleton [19][20], and thereby can directly translate mechanical cues and changes in extracellular matrix mechanics into alterations in chromatin structure and transcriptional activity [21].

2. LMNA-Related Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is characterized by enlargement and dilatation of one or both ventricles of the heart, which occurs together with impaired contractility and heart function [22]. The LMNA gene is the second most commonly mutated gene in familial dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), accounting for 5% to 8% of cases [23]. Patients carrying pathogenic LMNA mutations have a poor prognosis due to the high rate of sudden cardiac death resulting from malignant arrhythmias. Atrial fibrillation (AF), atrioventricular (AV) conduction block, ventricular tachycardia, and sudden cardiac death often precede the development of systolic dysfunction [24][25][26]. Although LMNA-related DCM is an adult-onset disease, it cannot be excluded that structural changes and arrhythmias may be present in early asymptomatic individuals [27].

To date, around 500 mutations and 300 protein variants have been reported for LMNA; detailed information on the different mutations is available through the UMD-LMNA mutation database (www.umd.be/LMNA, accessed on 3 January 2023). Most of the mutations associated with cardiomyopathies are located in the head and rod domains and are mostly truncation or missense mutations [28]. Heterozygous truncation mutations often result in lamin A/C haploinsufficiency due to a premature termination codon generated by insertions or deletions resulting in a frameshift, aberrant splice site, or nonsense mutations. A homozygous LMNA nonsense mutation (Y259X) has also been reported, resulting in a lethal phenotype [29]. LMNA missense mutations, on the other hand, are thought to mostly act through a dominant negative mechanism [28]. Patients carrying heterozygous mutations in LMNA in combination with mutations within other genes such as TTN, DES, SUN1/2, etc., display a particularly severe clinical cardiac phenotype [30][31][32][33][34].

Another mutation often used for modeling the LMNA LOF mutation is the p.R225X mutation, a nonsense mutation causing premature truncation of both lamin A and lamin C splice isoforms. Patients carrying this pathogenic mutation show early onset of AF, secondary AV block, and DCM [35]. Like Lmna−/− mice, homozygote Lmna R225X mice also exhibit retarded postnatal growth, conduction disorders, and DCM [36]. Other LOF mutations, e.g., K117fs and 28insA, also lead to a DCM phenotype. LMNA p. K117fs mutation is a frameshift mutation that leads to a premature translation-termination codon [37], whereas 28insA is an adenosine insertion mutation in exon 1 resulting similarly in a premature stop codon [38]. Messenger RNAs (mRNAs) that contain a premature stop codon often undergo degradation through the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) surveillance mechanism and thus can cause haploinsufficiency. Consistent with this, a significant decrease in lamin A/C protein levels is observed in K117fs iPSC-CMs as a result of NMD-mediated degradation of LMNA mRNA [37]. In addition to truncation mutations, which can result in LMNA haploinsufficiency, mutations such as N195K, T10I, R541S, and R337H also show reduced lamin A/C protein levels [39][40]. Patients carrying these pathogenic mutations also develop DCM [26][41][42]. It is still unclear why these mutations lead to decreased lamin A/C levels. Possible reasons could be that protein translation or the stability of lamin A/C are affected in mutant CMs. For example, although Lmna mRNA does not change, both lamin A and lamin C levels are decreased in CMs and MEFs derived from Lmna N195K/N195K mutant mice [39]. Interestingly, patients carrying different LMNA missense mutations resulting in DCM also exhibit lower protein levels [43]. To what extent the decrease in lamin A/C levels or changes in protein function result in disease pathogenesis is still largely unknown and needs further investigation.

Although it may seem that DCM is predominantly caused by LMNA haploinsufficiency, missense mutations in LMNA, which do not lead to changes in lamin A/C protein levels, also result in DCM. For example, LMNA K219T missense mutation causing severe DCM and heart failure with conduction system disease [44] does not lead to obvious changes in lamin A/C levels in K219T iPSC-CMs [45]. LMNA H222P missense mutation has been shown to cause Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD) and DCM in patients. Homozygous mice with the H222P mutation display muscular dystrophy, left ventricular dilatation, and conduction defects and die by 9 months of age [46]. Similarly to the K219T mutation, Western blot analysis of cardiac and skeletal muscle samples shows no obvious difference in lamin A/C protein levels between wild-type and Lmna H222P/H222P mice [47]. Interestingly, recent studies suggested a developmental origin of LMNA-related cardiac laminopathy. Lmna H222P/H222P embryonic hearts showed noncompaction, dilatation, and decreased heart function already at E13.5[48], while Lmna+/− and Lmna−/− embryonic hearts showed noncompaction cardiomyopathy with no decrease in ejection fraction [49]. Differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) harboring the Lmna p.H222P mutation revealed decreased expression of cardiac mesoderm marker genes, such as Eomes and Mesp1 as well as cardiac progenitor (CP) markers and impaired CM differentiation. This is in stark contrast to Lmna+/− and Lmna−/− mESCs, which showed premature CM differentiation [48][49], suggesting different mechanisms behind the heart phenotype caused by lamin A/C haploinsufficiency or changes in protein functionality.

Among laminopathy-associated missense mutations, the addition of proline is the most common. Proline addition can significantly alter protein structure. For example, LMNA S143P missense mutation causes DCM and disturbs the coiled-coil domain, thus affecting lamin A/C assembly into the nuclear lamina. This results in nuclear fragility and reduced cellular stress tolerance [50]. The addition of proline might also affect protein phosphorylation through proline-directed kinases, such as the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, cyclin-dependent protein kinase 5 (CDK5), glycogen synthase 3, etc. Mutations resulting in the addition of proline often result in striated muscle disease, suggesting a common underlying mechanism [51].

3. Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is an inherited heart muscle disorder that predominantly affects the right ventricle [52]. A progressive loss of myocytes and fibro-fatty replacement associated with arrhythmias in the right ventricular myocardium is a hallmark of the disease [53]. Mutations in desmosomal genes, such as Plakophilin 2 (PKP2), Desmoplakin (DSP), Desmoglein 2 (DSG2), Desmocollin 2 (DSC2), and junction plakoglobin (JUP), are the main cause of ARVC [54][55][56][57][58][59]. In addition, mutations in the calcium-handling protein Ryanodine Receptor 2 (RYR2) [60], Phospholamban (PLN) [61], the adherens junction protein Cadherin 2 (CDH2) [62], Integrin-Linked Kinase (ILK) [63], the signaling molecule Transforming Growth Factor-β3 (TGFB3) [64], the cytoskeletal structure protein Titin (TTN) [65], Desmin (DES) [66], transmembrane protein 43 (TMEM43), and lamin A/C (LMNA) have also been reported in ARVC [24][67][68][69].

In 2011, Quarta et al. first reported ARVC caused by mutations in LMNA. Four LMNA variants were identified: R190W, R644C, R72C, and G382V [24]. The R190W and R644C variants also cause DCM and left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC). In addition, R644C can also lead to lipodystrophy and atypical progeria, thus showing an extreme phenotypic diversity. ARVC patients with these four mutations all exhibit RV dilatation and systolic dysfunction. Histological examination of the right ventricular myocardium from R190W and G382V patients showed a loss of more than 50% of myocytes and extensive interstitial fibrosis and fatty replacement [24]. Interestingly, immunohistochemical staining showed significantly reduced plakoglobin expression at the intercalated discs in the myocardium, which could contribute to the development of ARVC [24]. M1K, W514X, and M384I mutations in LMNA have also been identified in ARVC. Patients with M1K and W514X mutations show RV dilatation, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, and complete atrioventricular block [69]. A patient with the M384I variant not only developed ARVC but also peripheral neuropathy and peroneal muscular atrophy [70].

So far, it remains unknown how LMNA mutations result in ARVC. Since LMNA is a ubiquitously expressed protein, its mechanoprotective function in cardiomyocytes, which can limit the progressive loss of myocytes, its role in the regulation of genes involved in cardiac contractility, and its important role in regulating cell fate choices, which may result in an excess of fibroblasts and adipocytes, might be involved. Tracing back the origins of fat tissue in a mouse model of ARVC, Lombardi et al. suggested that second heart field (SHF)-derived progenitor cells switch to an adipogenic fate through nuclear plakoglobin (JUP)-mediated Wnt signaling inhibition [71]. A subset of resident cardiac fibro-adipocyte progenitor cells characterized by PDGFRAposLinnegTHY1negDDR2neg expression signatures have been shown to be a major source of adipocytes in ARVC caused by Desmoplakin (DSP) haploinsufficiency [72]. Furthermore, the endocardium, epicardium, and cardiac mesenchymal stromal cells also serve as a source of adipocytes in the heart [73][74][75]. Because the endocardium and epicardium give rise to diverse cardiac cell lineages, including mesenchyme and adipocytes [76], via endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), lamin A/C function in regulating EMT [48] might also be a key mechanism driving ARVC pathogenesis.

4. Left Ventricle Noncompaction Cardiomyopathy

Left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) cardiomyopathy is a rare congenital heart disease resulting from abnormal development of the endocardium and myocardium. Patients with LVNC exhibit a thin compact myocardium and excessive trabeculation and can eventually develop progressive cardiac dysfunction followed by heart failure. LVNC can manifest together with other cardiomyopathies and congenital heart disease [77]. Studies have identified various genes associated with LVNC, such as TTN, MYH7, TNNT2, LDB3, MYBPC3, ACTC1, DSP, CASQ2, RBM20, and the intermediate filaments DES [78] and LMNA [79], with the two most affected genes being TTN and LMNA [80]. The first reported LMNA mutant variant causing LVNC is R190W, which is also associated with familial DCM and ARVC [81]. Another pathogenic LMNA variant causing LVNC is LMNA R644C. R644C mutation carriers show an extreme phenotypic diversity, ranging from DCM and LVNC to lipodystrophy and atypical progeria [82]. Parents and colleagues reported four family members with the LMNA R644C mutation, three of whom developed left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy with normal LV dimensions and function and without evidence of dysrhythmias [83]. Other mutations such as LMNA V74fs, R572C, and V445E have also been associated with LVNC. Patients with the V445E missense mutation are characterized by an arrhythmogenic form of LVNC, suggested to be due to dysfunctional SCN5A [80][84].

How LMNA mutations result in LVNC and the mechanisms underlying the high phenotypic diversity are largely unknown. Two recent studies demonstrated that Lmna H222P/H222P as well as Lmna−/− and Lmna+/− embryonic hearts exhibit noncompaction, suggesting these mouse models as important tools to study the developmental origin and the mechanisms behind LMNA-mediated noncompaction cardiomyopathy [48][49]. Interestingly, the researchers' own research revealed that Lmna LOF results in abnormal cell fate choices during cardiogenesis, i.e., promotes CM and represses endothelial cell fate. Since the crosstalk between CMs and endothelial cells is instrumental for proper cardiac development and myocardial compaction [85], abnormal cardiovascular cell fate choices and dysfunctional endothelium might also contribute to LVNC. Thus, understanding the link between alternative cell fate choices, changes in cell behavior, and tissue-specific phenotypes caused by pathogenic LMNA mutations would be an important question to address in further studies.

5. Restrictive Cardiomyopathy

Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is a rare cardiac disease characterized by increased myocardial stiffness resulting in impaired ventricular filling. Patients with RCM show enlarged atria and diastolic dysfunction, while systolic function and ventricular wall thicknesses are often normal until the later stages of the disease [86][87][88]. Although most causes of RCM are acquired, several gene mutations have also been identified in patients with RCM [86][87][88][89]. The most common mutated genes found in RCM are sarcomere-related genes such as TTN [90], TNNI3 [91], MYH7 [92], ACTC1 [93], etc. Mutations in non-sarcomere genes such as DES [94], TMEM87B [95], FLNC [96], etc., have also been reported. Recently, Paller et al. reported a truncation mutation of LMNA (c.835 delG:p.Glu279ArgfsX201) in an RCM patient who had a significant biatrial enlargement, atrial fibrillation, and skeletal muscle weakness. Both right and left ventricular size and function were normal, and histological analysis revealed cardiac hypertrophy and focal interstitial fibrosis in the endomyocardial tissue [97]. How Lmna mutations cause RCM is not known; a plausible mechanism could be the activation of profibrotic signaling, as discussed below.

6. Molecular Mechanisms Resulting in LMNA-Related Cardiomyopathy Pathogenesis

Since LMNA-related cardiomyopathies caused by distinct point mutations show phenotypic diversity, the precise molecular mechanisms resulting in disease pathogenesis are also distinct and complex. Taking into account the variety of different functions of the nuclear lamina, three central mechanisms have been suggested to drive disease pathogenesis.

The “mechanical hypothesis” proposes that disruption of the nuclear lamina causes increased nuclear fragility and increased susceptibility to mechanical stress [98]. This hypothesis is supported by observations that CMs from patients or mouse models with lamin A/C mutations exhibit nuclear rupture, DNA damage, and cell cycle arrest [42][49][99][100]. Interestingly, Lmna−/− non-CMs subjected to stretch show significantly increased DNA damage, further supporting the notion that the elevated cell death could be due to the inability of Lmna−/− CMs to respond adequately to mechanical stress [49]. Importantly, a recent study revealed that disrupting the LINC complex and thereby decoupling the nucleus/nucleoskeleton from the mechanical forces transduced by the cytoskeleton increases more than fivefold the lifespan of LMNA-deficient mice [101], pointing to therapeutic opportunities for patients carrying mutations resulting in nuclear fragility.

Myriad studies have demonstrated a role of lamins in regulating MAPK, TGF-β, Wnt–β-catenin, and Notch signaling cascades [102][103] and suggested that altered signaling is a key driver of LMNA-related dilated cardiomyopathy. For instance, LMNA-related cardiomyopathy shows a significant increase in myocardial fibrosis which contributes to left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure [24][39][104][105]. Profibrotic signaling, such as TGF-β, MAPK, and ERK signaling, is activated in Lmna H222P/H222P mice, and the partial inhibition of ERK and JNK signaling before the onset of cardiomyopathy in Lmna H222P/H222P mice significantly reduces cardiac fibrosis and prevents the development of left ventricle dilatation and decreased cardiac ejection fraction [105][106][107][108]. Indeed, therapies targeting intracellular signaling alterations are being developed in a preclinical setting [109].

Since nuclear lamins anchor chromatin at the nuclear periphery, the “chromatin hypothesis” suggests that chromatin alterations as a result of LMNA haploinsufficiency or mutation result in abnormal gene expression programs responsible for the disease phenotype [98]. In the last years, a number of studies using iPSC-CMs or mESC-CMs uncovered changes in chromatin architecture coupled to transcriptional changes in different ion channels such as SCN5A, CACNA1A/C/D, HCN4, SCN3b, and SCN4b, as well as Pdgfb pathway activation, which might explain the arrhythmogenic conduction defects in LMNA patients [37][45][49][110].

7. Advances in Therapeutic Strategies for LMNA-Related Cardiomyopathy

The clinical management of LMNA-related DCM includes pharmacological treatment with ACE inhibitors and beta blockers and implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICDs) [111][112]. Heart transplantation or ventricular assist devices may also be required for patients in the end stages of heart failure [111][112]. The inhibition of mTOR, MAPK, and LSD1 significantly rescues the LMNA-related DCM phenotype in mice [48][105][113], and a novel and selective p38 MAPK inhibitor is now in a phase 3 clinical trial in LMNA-related DCM [114]. In addition, CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing strategies have been used in LMNA-caused Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS) and show promising results [115][116][117]. By using guide RNAs (gRNAs) that target LMNA exon 11 to specifically interfere with lamin A/progerin expression, both Santiago-Fernández et al. and Beyret et al. show a reduced progerin expression and improvement in the progeria phenotype in an HGPS mouse model [115][116]. However, off-target effects, e.g., resulting from insertion and deletions during non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), are a major concern. To overcome these limitations, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated base pair editing systems have been used in HGPS mice [117]. Base pair editing systems could modify the genome without the need of double-strand DNA breaks or donor DNA templates [118]. Two classes of DNA base editors have been reported: cytosine base editors (CBEs), which convert C:G to T:A, and adenine base editors (ABEs) which convert A:T to G:C [119][120]. Systemic injection of a single dose of dual AAV9 encoding ABE and sgRNA into an HGPS mouse model significantly extends the median lifespan of the mice, improves aortic health, and fully rescues VSMC counts as well as adventitial fibrosis [117]. Despite the power of the base pair editing technology, a major limitation is the inability to edit the genome beyond four transition mutations. Prime editing represents a novel approach which is not only suitable for all transition and transversion mutations but also for small insertion and deletion mutations [121]. Similar to base pair editing, prime editing does not require double-strand DNA breaks or donor DNA templates [121] and could be used in the correction of genetic cardiomyopathies.

References

- Schreiber, K.H.; Kennedy, B.K. When lamins go bad: Nuclear structure and disease. Cell 2013, 152, 1365–1375.

- Osmanagic-Myers, S.; Foisner, R. The structural and gene expression hypotheses in laminopathic diseases-not so different after all. Mol. Biol. Cell 2019, 30, 1786–1790.

- McKeon, F.D.; Kirschner, M.W.; Caput, D. Homologies in both primary and secondary structure between nuclear envelope and intermediate filament proteins. Nature 1986, 319, 463–468.

- Fisher, D.Z.; Chaudhary, N.; Blobel, G. cDNA sequencing of nuclear lamins A and C reveals primary and secondary structural homology to intermediate filament proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 6450–6454.

- Gruenbaum, Y.; Foisner, R. Lamins: Nuclear intermediate filament proteins with fundamental functions in nuclear mechanics and genome regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015, 84, 131–164.

- Lin, F.; Worman, H.J. Structural organization of the human gene (LMNB1) encoding nuclear lamin B1. Genomics 1995, 27, 230–236.

- Vorburger, K.; Lehner, C.; Kitten, G.; Eppenberger, H.; Nigg, E. A second higher vertebrate B-type lamin: cDNA sequence determination and in vitro processing of chicken lamin B2. J. Mol. Biol. 1989, 208, 405–415.

- Peter, M.; Kitten, G.; Lehner, C.; Vorburger, K.; Bailer, S.; Maridor, G.; Nigg, E. Cloning and sequencing of cDNA clones encoding chicken lamins A and B1 and comparison of the primary structures of vertebrate A-and B-type lamins. J. Mol. Biol. 1989, 208, 393–404.

- Höger, T.H.; Zatloukal, K.; Waizenegger, I.; Krohne, G. Characterization of a second highly conserved B-type lamin present in cells previously thought to contain only a single B-type lamin. Chromosoma 1990, 99, 379–390.

- Turgay, Y.; Eibauer, M.; Goldman, A.E.; Shimi, T.; Khayat, M.; Ben-Harush, K.; Dubrovsky-Gaupp, A.; Sapra, K.T.; Goldman, R.D.; Medalia, O. The molecular architecture of lamins in somatic cells. Nature 2017, 543, 261–264.

- Burke, B.; Stewart, C.L. The nuclear lamins: Flexibility in function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 14, 13–24.

- Walling, B.L.; Murphy, P.M. Protean regulation of leukocyte function by nuclear lamins. Trends Immunol. 2021, 42, 323–335.

- Shimi, T.; Kittisopikul, M.; Tran, J.; Goldman, A.E.; Adam, S.A.; Zheng, Y.; Jaqaman, K.; Goldman, R.D. Structural organization of nuclear lamins A, C, B1, and B2 revealed by superresolution microscopy. Mol. Biol. Cell 2015, 26, 4075–4086.

- Nmezi, B.; Xu, J.; Fu, R.; Armiger, T.J.; Rodriguez-Bey, G.; Powell, J.S.; Ma, H.; Sullivan, M.; Tu, Y.; Chen, N.Y. Concentric organization of A-and B-type lamins predicts their distinct roles in the spatial organization and stability of the nuclear lamina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4307–4315.

- van Steensel, B.; Belmont, A.S. Lamina-Associated Domains: Links with Chromosome Architecture, Heterochromatin, and Gene Repression. Cell 2017, 169, 780–791.

- Reddy, K.L.; Zullo, J.M.; Bertolino, E.; Singh, H. Transcriptional repression mediated by repositioning of genes to the nuclear lamina. Nature 2008, 452, 243–247.

- Wen, B.; Wu, H.; Shinkai, Y.; Irizarry, R.A.; Feinberg, A.P. Large histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylated chromatin blocks distinguish differentiated from embryonic stem cells. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 246–250.

- Gesson, K.; Rescheneder, P.; Skoruppa, M.P.; von Haeseler, A.; Dechat, T.; Foisner, R. A-type lamins bind both hetero- and euchromatin, the latter being regulated by lamina-associated polypeptide 2 alpha. Genome Res. 2016, 26, 462–473.

- Jahed, Z.; Mofrad, M.R. The nucleus feels the force, LINCed in or not! Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2019, 58, 114–119.

- Stroud, M.J.; Banerjee, I.; Veevers, J.; Chen, J. Linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton complex proteins in cardiac structure, function, and disease. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 538–548.

- Lityagina, O.; Dobreva, G. The LINC Between Mechanical Forces and Chromatin. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 710809.

- Gerull, B.; Klaassen, S.; Brodehl, A. The Genetic Landscape of Cardiomyopathies. In Genetic Causes of Cardiac Disease; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019.

- McNally, E.M.; Mestroni, L. Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Genetic Determinants and Mechanisms. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 731–748.

- Quarta, G.; Syrris, P.; Ashworth, M.; Jenkins, S.; Zuborne Alapi, K.; Morgan, J.; Muir, A.; Pantazis, A.; McKenna, W.J.; Elliott, P.M. Mutations in the Lamin A/C gene mimic arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 1128–1136.

- Van Rijsingen, I.A.; Arbustini, E.; Elliott, P.M.; Mogensen, J.; Hermans-van Ast, J.F.; Van Der Kooi, A.J.; Van Tintelen, J.P.; Van Den Berg, M.P.; Pilotto, A.; Pasotti, M. Risk factors for malignant ventricular arrhythmias in lamin A/C mutation carriers: A European cohort study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 493–500.

- Fatkin, D.; MacRae, C.; Sasaki, T.; Wolff, M.R.; Porcu, M.; Frenneaux, M.; Atherton, J.; Vidaillet Jr, H.J.; Spudich, S.; De Girolami, U. Missense mutations in the rod domain of the lamin A/C gene as causes of dilated cardiomyopathy and conduction-system disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 1715–1724.

- Kumar, S.; Baldinger, S.H.; Gandjbakhch, E.; Maury, P.; Sellal, J.-M.; Androulakis, A.F.; Waintraub, X.; Charron, P.; Rollin, A.; Richard, P. Long-term arrhythmic and nonarrhythmic outcomes of lamin A/C mutation carriers. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 2299–2307.

- Nishiuchi, S.; Makiyama, T.; Aiba, T.; Nakajima, K.; Hirose, S.; Kohjitani, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Harita, T.; Hayano, M.; Wuriyanghai, Y. Gene-based risk stratification for cardiac disorders in LMNA mutation carriers. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2017, 10, e001603.

- van Engelen, B.G.; Muchir, A.; Hutchison, C.J.; van der Kooi, A.J.; Bonne, G.; Lammens, M. The lethal phenotype of a homozygous nonsense mutation in the lamin A/C gene. Neurology 2005, 64, 374–376.

- Roncarati, R.; Viviani Anselmi, C.; Krawitz, P.; Lattanzi, G.; von Kodolitsch, Y.; Perrot, A.; di Pasquale, E.; Papa, L.; Portararo, P.; Columbaro, M.; et al. Doubly heterozygous LMNA and TTN mutations revealed by exome sequencing in a severe form of dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 21, 1105–1111.

- Galata, Z.; Kloukina, I.; Kostavasili, I.; Varela, A.; Davos, C.H.; Makridakis, M.; Bonne, G.; Capetanaki, Y. Amelioration of desmin network defects by αB-crystallin overexpression confers cardioprotection in a mouse model of dilated cardiomyopathy caused by LMNA gene mutation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018, 125, 73–86.

- Maggi, L.; Mavroidis, M.; Psarras, S.; Capetanaki, Y.; Lattanzi, G. Skeletal and cardiac muscle disorders caused by mutations in genes encoding intermediate filament proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4256.

- Vincenzo, M.; Michelangelo, M.; Costanza, S.; Francesca, T.; Lucia, C.; Greta, A.; Anna, R.; Fulvia, B.; Adelaide, C.M.; Giovanna, L. A Single mtDNA Deletion in Association with a LMNA Gene New Frameshift Variant: A Case Report. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2022, 9, 457–462.

- Meinke, P.; Mattioli, E.; Haque, F.; Antoku, S.; Columbaro, M.; Straatman, K.R.; Worman, H.J.; Gundersen, G.G.; Lattanzi, G.; Wehnert, M. Muscular dystrophy-associated SUN1 and SUN2 variants disrupt nuclear-cytoskeletal connections and myonuclear organization. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004605.

- Lee, Y.K.; Jiang, Y.; Ran, X.R.; Lau, Y.M.; Ng, K.M.; Lai, W.H.; Siu, C.W.; Tse, H.F. Recent advances in animal and human pluripotent stem cell modeling of cardiac laminopathy. Stem Cell Res. 2016, 7, 139.

- Cai, Z.-J.; Lee, Y.-K.; Lau, Y.-M.; Ho, J.C.-Y.; Lai, W.-H.; Wong, N.L.-Y.; Huang, D.; Hai, J.-j.; Ng, K.-M.; Tse, H.-F. Expression of Lmna-R225X nonsense mutation results in dilated cardiomyopathy and conduction disorders (DCM-CD) in mice: Impact of exercise training. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 298, 85–92.

- Lee, J.; Termglinchan, V.; Diecke, S.; Itzhaki, I.; Lam, C.K.; Garg, P.; Lau, E.; Greenhaw, M.; Seeger, T.; Wu, H. Activation of PDGF pathway links LMNA mutation to dilated cardiomyopathy. Nature 2019, 572, 335–340.

- Sebillon, P.; Bouchier, C.; Bidot, L.; Bonne, G.; Ahamed, K.; Charron, P.; Drouin-Garraud, V.; Millaire, A.; Desrumeaux, G.; Benaiche, A. Expanding the phenotype of LMNA mutations in dilated cardiomyopathy and functional consequences of these mutations. J. Med. Genet. 2003, 40, 560–567.

- Mounkes, L.C.; Kozlov, S.V.; Rottman, J.N.; Stewart, C.L. Expression of an LMNA-N195K variant of A-type lamins results in cardiac conduction defects and death in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 2167–2180.

- Shah, P.P.; Lv, W.; Rhoades, J.H.; Poleshko, A.; Abbey, D.; Caporizzo, M.A.; Linares-Saldana, R.; Heffler, J.G.; Sayed, N.; Thomas, D. Pathogenic LMNA variants disrupt cardiac lamina-chromatin interactions and de-repress alternative fate genes. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 938–954.e939.

- Bonne, G.; Mercuri, E.; Muchir, A.; Urtizberea, A.; Bécane, H.M.; Recan, D.; Merlini, L.; Wehnert, M.; Boor, R.; Reuner, U.; et al. Clinical and molecular genetic spectrum of autosomal dominant Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy due to mutations of the lamin A/C gene. Ann. Neurol. 2000, 48, 170–180.

- Gupta, P.; Bilinska, Z.T.; Sylvius, N.; Boudreau, E.; Veinot, J.P.; Labib, S.; Bolongo, P.M.; Hamza, A.; Jackson, T.; Ploski, R. Genetic and ultrastructural studies in dilated cardiomyopathy patients: A large deletion in the lamin A/C gene is associated with cardiomyocyte nuclear envelope disruption. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2010, 105, 365–377.

- Cheedipudi, S.M.; Matkovich, S.J.; Coarfa, C.; Hu, X.; Robertson, M.J.; Sweet, M.; Taylor, M.; Mestroni, L.; Cleveland, J.; Willerson, J.T.; et al. Genomic Reorganization of Lamin-Associated Domains in Cardiac Myocytes Is Associated With Differential Gene Expression and DNA Methylation in Human Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1198–1213.

- Perrot, A.; Hussein, S.; Ruppert, V.; Schmidt, H.H.; Wehnert, M.S.; Duong, N.T.; Posch, M.G.; Panek, A.; Dietz, R.; Kindermann, I.; et al. Identification of mutational hot spots in LMNA encoding lamin A/C in patients with familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2009, 104, 90–99.

- Salvarani, N.; Crasto, S.; Miragoli, M.; Bertero, A.; Paulis, M.; Kunderfranco, P.; Serio, S.; Forni, A.; Lucarelli, C.; Dal Ferro, M.; et al. The K219T-Lamin mutation induces conduction defects through epigenetic inhibition of SCN5A in human cardiac laminopathy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2267.

- Arimura, T.; Helbling-Leclerc, A.; Massart, C.; Varnous, S.; Niel, F.; Lacene, E.; Fromes, Y.; Toussaint, M.; Mura, A.-M.; Keller, D.I. Mouse model carrying H222P-Lmna mutation develops muscular dystrophy and dilated cardiomyopathy similar to human striated muscle laminopathies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 155–169.

- Wada, E.; Kato, M.; Yamashita, K.; Kokuba, H.; Hayashi, Y.K. Deficiency of emerin contributes differently to the pathogenesis of skeletal and cardiac muscles in LmnaH222P/H222P mutant mice. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221512.

- Guenantin, A.C.; Jebeniani, I.; Leschik, J.; Watrin, E.; Puceat, M. Targeting the histone demethylase LSD1 prevents cardiomyopathy in a mouse model of laminopathy. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e136488.

- Wang, Y.; Elsherbiny, A.; Kessler, L.; Cordero, J.; Shi, H.; Serke, H.; Lityagina, O.; Trogisch, F.A.; Mohammadi, M.M.; El-Battrawy, I. Lamin A/C-dependent chromatin architecture safeguards nave pluripotency to prevent aberrant cardiovascular cell fate and function. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6663.

- West, G.; Gullmets, J.; Virtanen, L.; Li, S.-P.; Keinänen, A.; Shimi, T.; Mauermann, M.; Heliö, T.; Kaartinen, M.; Ollila, L. Deleterious assembly of the lamin A/C mutant p. S143P causes ER stress in familial dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 2732–2743.

- Lin, E.W.; Brady, G.F.; Kwan, R.; Nesvizhskii, A.I.; Omary, M.B. Genotype-phenotype analysis of LMNA-related diseases predicts phenotype-selective alterations in lamin phosphorylation. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 9051–9073.

- Gerull, B.; Brodehl, A. Insights Into Genetics and Pathophysiology of Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2021, 18, 378–390.

- Marcus, F.I.; McKenna, W.J.; Sherrill, D.; Basso, C.; Bauce, B.; Bluemke, D.A.; Calkins, H.; Corrado, D.; Cox, M.G.; Daubert, J.P. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: Proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation 2010, 121, 1533–1541.

- Joshi-Mukherjee, R.; Coombs, W.; Musa, H.; Oxford, E.; Taffet, S.; Delmar, M. Characterization of the molecular phenotype of two arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)-related plakophilin-2 (PKP2) mutations. Heart Rhythm. 2008, 5, 1715–1723.

- Awad, M.M.; Dalal, D.; Tichnell, C.; James, C.; Tucker, A.; Abraham, T.; Spevak, P.J.; Calkins, H.; Judge, D.P. Recessive arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia due to novel cryptic splice mutation in PKP2. Hum. Mutat. 2006, 27, 1157.

- Yang, Z.; Bowles, N.E.; Scherer, S.E.; Taylor, M.D.; Kearney, D.L.; Ge, S.; Nadvoretskiy, V.V.; DeFreitas, G.; Carabello, B.; Brandon, L.I. Desmosomal dysfunction due to mutations in desmoplakin causes arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2006, 99, 646–655.

- Awad, M.M.; Dalal, D.; Cho, E.; Amat-Alarcon, N.; James, C.; Tichnell, C.; Tucker, A.; Russell, S.D.; Bluemke, D.A.; Dietz, H.C. DSG2 mutations contribute to arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 79, 136–142.

- Corrado, D.; Thiene, G. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: Clinical impact of molecular genetic studies. Circulation 2006, 113, 1634–1637.

- Brodehl, A.; Weiss, J.; Debus, J.D.; Stanasiuk, C.; Klauke, B.; Deutsch, M.A.; Fox, H.; Bax, J.; Ebbinghaus, H.; Gartner, A.; et al. A homozygous DSC2 deletion associated with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy is caused by uniparental isodisomy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 141, 17–29.

- Tiso, N.; Stephan, D.A.; Nava, A.; Bagattin, A.; Devaney, J.M.; Stanchi, F.; Larderet, G.; Brahmbhatt, B.; Brown, K.; Bauce, B. Identification of mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene in families affected with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 2 (ARVD2). Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 189–194.

- Zwaag, P.; Rijsingen, I.; Ruite, R. Recurrent and founder mutations in the Netherlands—Phospholamban p.Arg14del mutation causes arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Neth. Heart J. 2013, 21, 286–293.

- Mayosi, B.M.; Fish, M.; Shaboodien, G.; Mastantuono, E.; Kraus, S.; Wieland, T.; Kotta, M.-C.; Chin, A.; Laing, N.; Ntusi, N.B.A.; et al. Identification of Cadherin 2 (CDH2) Mutations in Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2017, 10, e001605.

- Brodehl, A.; Rezazadeh, S.; Williams, T.; Munsie, N.M.; Liedtke, D.; Oh, T.; Ferrier, R.; Shen, Y.; Jones, S.J.M.; Stiegler, A.L.; et al. Mutations in ILK, encoding integrin-linked kinase, are associated with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Transl. Res. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2019, 208, 15–29.

- Beffagna, G.; Occhi, G.; Nava, A.; Vitiello, L.; Ditadi, A.; Basso, C.; Bauce, B.; Carraro, G.; Thiene, G.; Towbin, J.A. Regulatory mutations in transforming growth factor-β3 gene cause arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 1. Cardiovasc. Res. 2005, 65, 366–373.

- Taylor, M.; Graw, S.; Sinagra, G.; Barnes, C.; Slavov, D.; Brun, F.; Pinamonti, B.; Salcedo, E.E.; Sauer, W.; Pyxaras, S. Genetic variation in titin in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy–overlap syndromes. Circulation 2011, 124, 876–885.

- Protonotarios, A.; Brodehl, A.; Asimaki, A.; Jager, J.; Quinn, E.; Stanasiuk, C.; Ratnavadivel, S.; Futema, M.; Akhtar, M.M.; Gossios, T.D.; et al. The Novel Desmin Variant p.Leu115Ile Is Associated With a Unique Form of Biventricular Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Can. J. Cardiol. 2021, 37, 857–866.

- Hodgkinson, K.; Connors, S.; Merner, N.; Haywood, A.; Young, T.L.; McKenna, W.; Gallagher, B.; Curtis, F.; Bassett, A.; Parfrey, P. The natural history of a genetic subtype of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy caused by a p. S358L mutation in TMEM43. Clin. Genet. 2013, 83, 321–331.

- Merner, N.D.; Hodgkinson, K.A.; Haywood, A.F.; Connors, S.; French, V.M.; Drenckhahn, J.-D.; Kupprion, C.; Ramadanova, K.; Thierfelder, L.; McKenna, W. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 5 is a fully penetrant, lethal arrhythmic disorder caused by a missense mutation in the TMEM43 gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 82, 809–821.

- Kato, K.; Takahashi, N.; Fujii, Y.; Umehara, A.; Nishiuchi, S.; Makiyama, T.; Ohno, S.; Horie, M. LMNA cardiomyopathy detected in Japanese arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy cohort. J. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 346–351.

- Liang, J.J.; Goodsell, K.; Grogan, M.; Ackerman, M.J. LMNA-mediated arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and charcot-marie-tooth type 2B1: A patient-discovered unifying diagnosis. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2016, 27, 868–871.

- Lombardi, R.; Dong, J.; Rodriguez, G.; Bell, A.; Leung, T.K.; Schwartz, R.J.; Willerson, J.T.; Brugada, R.; Marian, A.J. Genetic fate mapping identifies second heart field progenitor cells as a source of adipocytes in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 1076–1084.

- Lombardi, R.; Chen, S.N.; Ruggiero, A.; Gurha, P.; Czernuszewicz, G.Z.; Willerson, J.T.; Marian, A.J. Cardiac fibro-adipocyte progenitors express desmosome proteins and preferentially differentiate to adipocytes upon deletion of the desmoplakin gene. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 41–54.

- Matthes, S.A.; Taffet, S.; Delmar, M. Plakophilin-2 and the migration, differentiation and transformation of cells derived from the epicardium of neonatal rat hearts. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2011, 18, 73–84.

- Zhang, H.; Pu, W.; Li, G.; Huang, X.; He, L.; Tian, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S.M.; Sucov, H.M. Endocardium minimally contributes to coronary endothelium in the embryonic ventricular free walls. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1880–1893.

- Sommariva, E.; Brambilla, S.; Carbucicchio, C.; Gambini, E.; Meraviglia, V.; Dello Russo, A.; Farina, F.; Casella, M.; Catto, V.; Pontone, G. Cardiac mesenchymal stromal cells are a source of adipocytes in arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 1835–1846.

- Zhang, H.; Lui, K.O.; Zhou, B. Endocardial Cell Plasticity in Cardiac Development, Diseases and Regeneration. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 774–789.

- Arbustini, E.; Favalli, V.; Narula, N.; Serio, A.; Grasso, M. Left Ventricular Noncompaction: A Distinct Genetic Cardiomyopathy? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 949–966.

- Kulikova, O.; Brodehl, A.; Kiseleva, A.; Myasnikov, R.; Meshkov, A.; Stanasiuk, C.; Gartner, A.; Divashuk, M.; Sotnikova, E.; Koretskiy, S.; et al. The Desmin (DES) Mutation p.A337P Is Associated with Left-Ventricular Non-Compaction Cardiomyopathy. Genes 2021, 12, 121.

- Probst, S.; Oechslin, E.; Schuler, P.; Greutmann, M.; Boyé, P.; Knirsch, W.; Berger, F.; Thierfelder, L.; Jenni, R.; Klaassen, S. Sarcomere gene mutations in isolated left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy do not predict clinical phenotype. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2011, 4, 367–374.

- Sedaghat-Hamedani, F.; Haas, J.; Zhu, F.; Geier, C.; Kayvanpour, E.; Liss, M.; Lai, A.; Frese, K.; Pribe-Wolferts, R.; Amr, A. Clinical genetics and outcome of left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 3449–3460.

- Hermida-Prieto, M.; Monserrat, L.; Castro-Beiras, A.; Laredo, R.; Soler, R.; Peteiro, J.; Rodríguez, E.; Bouzas, B.; Álvarez, N.; Muñiz, J. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy and isolated left ventricular noncompaction associated with lamin A/C gene mutations. Am. J. Cardiol. 2004, 94, 50–54.

- Rankin, J.; Auer-Grumbach, M.; Bagg, W.; Colclough, K.; Duong, N.T.; Fenton-May, J.; Hattersley, A.; Hudson, J.; Jardine, P.; Josifova, D. Extreme phenotypic diversity and nonpenetrance in families with the LMNA gene mutation R644C. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2008, 146, 1530–1542.

- Parent, J.J.; Towbin, J.A.; Jefferies, J.L. Left ventricular noncompaction in a family with lamin A/C gene mutation. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2015, 42, 73.

- Liu, Z.; Shan, H.; Huang, J.; Li, N.; Hou, C.; Pu, J. A novel lamin A/C gene missense mutation (445 V > E) in immunoglobulin-like fold associated with left ventricular non-compaction. Europace 2016, 18, 617–622.

- Tian, Y.; Morrisey, E.E. Importance of myocyte-nonmyocyte interactions in cardiac development and disease. Circ. Res. 2012, 110, 1023–1034.

- Muchtar, E.; Blauwet, L.A.; Gertz, M.A. Restrictive cardiomyopathy: Genetics, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and therapy. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 819–837.

- Nihoyannopoulos, P.; Dawson, D. Restrictive cardiomyopathies. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2009, 10, iii23–iii33.

- Mogensen, J.; Arbustini, E. Restrictive cardiomyopathy. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2009, 24, 214–220.

- Brodehl, A.; Gerull, B. Genetic Insights into Primary Restrictive Cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2094.

- Peled, Y.; Gramlich, M.; Yoskovitz, G.; Feinberg, M.S.; Afek, A.; Polak-Charcon, S.; Pras, E.; Sela, B.A.; Konen, E.; Weissbrod, O.; et al. Titin mutation in familial restrictive cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 171, 24–30.

- Kostareva, A.; Gudkova, A.; Sjöberg, G.; Mörner, S.; Semernin, E.; Krutikov, A.; Shlyakhto, E.; Sejersen, T. Deletion in TNNI3 gene is associated with restrictive cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2009, 131, 410–412.

- Greenway, S.C.; Wilson, G.J.; Wilson, J.; George, K.; Kantor, P.F. Sudden death in an infant with angina, restrictive cardiomyopathy, and coronary artery bridging: An unusual phenotype for a β-myosin heavy chain (MYH7) sarcomeric protein mutation. Circ. Heart Fail. 2012, 5, e92–e93.

- Kaski, J.P.; Syrris, P.; Burch, M.; Tome-Esteban, M.-T.; Fenton, M.; Christiansen, M.; Andersen, P.S.; Sebire, N.; Ashworth, M.; Deanfield, J.E. Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy in children is caused by mutations in cardiac sarcomere protein genes. Heart 2008, 94, 1478–1484.

- Brodehl, A.; Pour Hakimi, S.A.; Stanasiuk, C.; Ratnavadivel, S.; Hendig, D.; Gaertner, A.; Gerull, B.; Gummert, J.; Paluszkiewicz, L.; Milting, H. Restrictive Cardiomyopathy is Caused by a Novel Homozygous Desmin (DES) Mutation p.Y122H Leading to a Severe Filament Assembly Defect. Genes 2019, 10, 918.

- Yu, H.-C.; Coughlin, C.R.; Geiger, E.A.; Salvador, B.J.; Elias, E.R.; Cavanaugh, J.L.; Chatfield, K.C.; Miyamoto, S.D.; Shaikh, T.H. Discovery of a potentially deleterious variant in TMEM87B in a patient with a hemizygous 2q13 microdeletion suggests a recessive condition characterized by congenital heart disease and restrictive cardiomyopathy. Mol. Case Stud. 2016, 2, a000844.

- Brodehl, A.; Ferrier, R.A.; Hamilton, S.J.; Greenway, S.C.; Brundler, M.-A.; Yu, W.; Gibson, W.T.; McKinnon, M.L.; McGillivray, B.C.; Alvarez, N.; et al. Mutations in FLNC are Associated with Familial Restrictive Cardiomyopathy. Hum. Mutat. 2016, 37, 269–279.

- Paller, M.S.; Martin, C.M.; Pierpont, M.E. Restrictive cardiomyopathy: An unusual phenotype of a lamin A variant. ESC Heart Fail. 2018, 5, 724–726.

- Brayson, D.; Shanahan, C.M. Current insights into LMNA cardiomyopathies: Existing models and missing LINCs. Nucleus 2017, 8, 17–33.

- Nikolova, V.; Leimena, C.; Mcmahon, A.C.; Tan, A.C.; Chandar, S.; Jogia, D.; Kesteven, S.H.; Michalicek, J.; Otway, R.; Verheyen, F. Defects in nuclear structure and function promote dilated cardiomyopathy in lamin A/C–deficient mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 357–369.

- Cho, S.; Vashisth, M.; Abbas, A.; Majkut, S.; Vogel, K.; Xia, Y.; Ivanovska, I.L.; Irianto, J.; Tewari, M.; Zhu, K. Mechanosensing by the lamina protects against nuclear rupture, DNA damage, and cell-cycle arrest. Dev. Cell 2019, 49, 920–935.e5.

- Chai, R.J.; Werner, H.; Li, P.Y.; Lee, Y.L.; Nyein, K.T.; Solovei, I.; Luu, T.D.A.; Sharma, B.; Navasankari, R.; Maric, M.; et al. Disrupting the LINC complex by AAV mediated gene transduction prevents progression of Lamin induced cardiomyopathy. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4722.

- Andres, V.; Gonzalez, J.M. Role of A-type lamins in signaling, transcription, and chromatin organization. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 187, 945–957.

- Bernasconi, P.; Carboni, N.; Ricci, G.; Siciliano, G.; Lattanzi, G. Elevated TGF β2 serum levels in Emery-Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy: Implications for myocyte and tenocyte differentiation and fibrogenic processes. Nucleus 2018, 9, 292–304.

- Chatzifrangkeskou, M.; Le Dour, C.; Wu, W.; Morrow, J.P.; Joseph, L.C.; Beuvin, M.; Sera, F.; Homma, S.; Vignier, N.; Mougenot, N.; et al. ERK1/2 directly acts on CTGF/CCN2 expression to mediate myocardial fibrosis in cardiomyopathy caused by mutations in the lamin A/C gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 2220–2233.

- Wu, W.; Muchir, A.; Shan, J.; Bonne, G.; Worman, H.J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors improve heart function and prevent fibrosis in cardiomyopathy caused by mutation in lamin A/C gene. Circulation 2011, 123, 53–61.

- Muchir, A.; Pavlidis, P.; Decostre, V.; Herron, A.J.; Arimura, T.; Bonne, G.; Worman, H.J. Activation of MAPK pathways links LMNA mutations to cardiomyopathy in Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1282–1293.

- Wu, W.; Shan, J.; Bonne, G.; Worman, H.J.; Muchir, A. Pharmacological inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling prevents cardiomyopathy caused by mutation in LMNA gene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2010, 1802, 632–638.

- Umbarkar, P.; Tousif, S.; Singh, A.P. Fibroblast GSK-3α Promotes Fibrosis via RAF-MEK-ERK Pathway in the Injured Heart. Circ. Res. 2022, 131, 620–636.

- Cattin, M.E.; Muchir, A.; Bonne, G. ‘State-of-the-heart’ of cardiac laminopathies. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2013, 28, 297–304.

- Bertero, A.; Fields, P.A.; Smith, A.S.; Leonard, A.; Beussman, K.; Sniadecki, N.J.; Kim, D.-H.; Tse, H.-F.; Pabon, L.; Shendure, J. Chromatin compartment dynamics in a haploinsufficient model of cardiac laminopathy. J. Cell Biol. 2019, 218, 2919–2944.

- Hershberger, R.E.; Morales, A.; Siegfried, J.D. Clinical and genetic issues in dilated cardiomyopathy: A review for genetics professionals. Genet. Med. 2010, 12, 655–667.

- Hershberger, R.E.; Jordan, E. LMNA-Related Dilated Cardiomyopathy; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2022.

- Ramos, F.J.; Chen, S.C.; Garelick, M.G.; Dai, D.F.; Liao, C.Y.; Schreiber, K.H.; MacKay, V.L.; An, E.H.; Strong, R.; Ladiges, W.C.; et al. Rapamycin reverses elevated mTORC1 signaling in lamin A/C-deficient mice, rescues cardiac and skeletal muscle function, and extends survival. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 144ra103.

- MacRae, C.; Taylor, M.; Mestroni, L.; Moses, J.; Ashley, E.; Wheeler, M.; Lakdawala, N.; Hershberger, R.; Ptaszynski, M.; Sandor, V. Phase 2 study of a797, an oral, selective p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor, in patients with lamin a/c-related dilated cardiomyopathy. In Proceedings of European Heart Journal; Oxford Univ Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; p. 1011.

- Santiago-Fernández, O.; Osorio, F.G.; Quesada, V.; Rodríguez, F.; Basso, S.; Maeso, D.; Rolas, L.; Barkaway, A.; Nourshargh, S.; Folgueras, A.R. Development of a CRISPR/Cas9-based therapy for Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 423–426.

- Beyret, E.; Liao, H.K.; Yamamoto, M.; Hernandez-Benitez, R.; Fu, Y.; Erikson, G. Single-dose CRISPR-Cas9 therapy extends lifespan of mice with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 419–422.

- Koblan, L.W.; Erdos, M.R.; Wilson, C.; Cabral, W.A.; Levy, J.M.; Xiong, Z.-M.; Tavarez, U.L.; Davison, L.M.; Gete, Y.G.; Mao, X.; et al. In vivo base editing rescues Hutchinson Gilford progeria syndrome in mice. Nature 2021, 589, 608–614.

- Anzalone, A.V.; Koblan, L.W.; Liu, D.R. Genome editing with CRISPR–Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 824–844.

- Gaudelli, N.M.; Komor, A.C.; Rees, H.A.; Packer, M.S.; Liu, D.R. Programmable base editing of AT to GC in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 2017, 551, 464–471.

- Zuris, J.A.; Liu, D.R.; Packer, M.S.; Komor, A.C.; Kim, Y.B. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 2016, 533, 420–424.

- Anzalone, A.V.; Randolph, P.B.; Davis, J.R.; Sousa, A.A.; Koblan, L.W.; Levy, J.M.; Chen, P.J.; Christopher, W.; Newby, G.A.; Aditya, R. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 2019, 576, 149–157.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cardiac & Cardiovascular Systems

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

23 Mar 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No