| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nicola Perrotti | -- | 2813 | 2023-03-16 14:51:48 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | + 5 word(s) | 2818 | 2023-03-17 04:59:30 | | |

Video Upload Options

Gene variants may have functional consequences on the protein product. The variants can be classified as loss of function (LOF) when the protein function is reduced or lost and gain of function (GOF) when the protein function is enhanced or a new function is acquired. Kinase inhibitors have been used for many years in tumor therapy, and new monoclonal antibodies—as well as small inhibitory molecules with different indications in tumor therapy—are approved every year by the regulatory agencies. human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) inhibitors are currently used in HER2-positive carcinomas, including breast, colon, and non-small-cell lung (NSCLC) cancers, Abl inhibitors are used in chronic myeloid leukemia.

1. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex

1.1. Clinical Manifestation

1.2. Genetics of TSC

1.3. Inhibition of mTOR

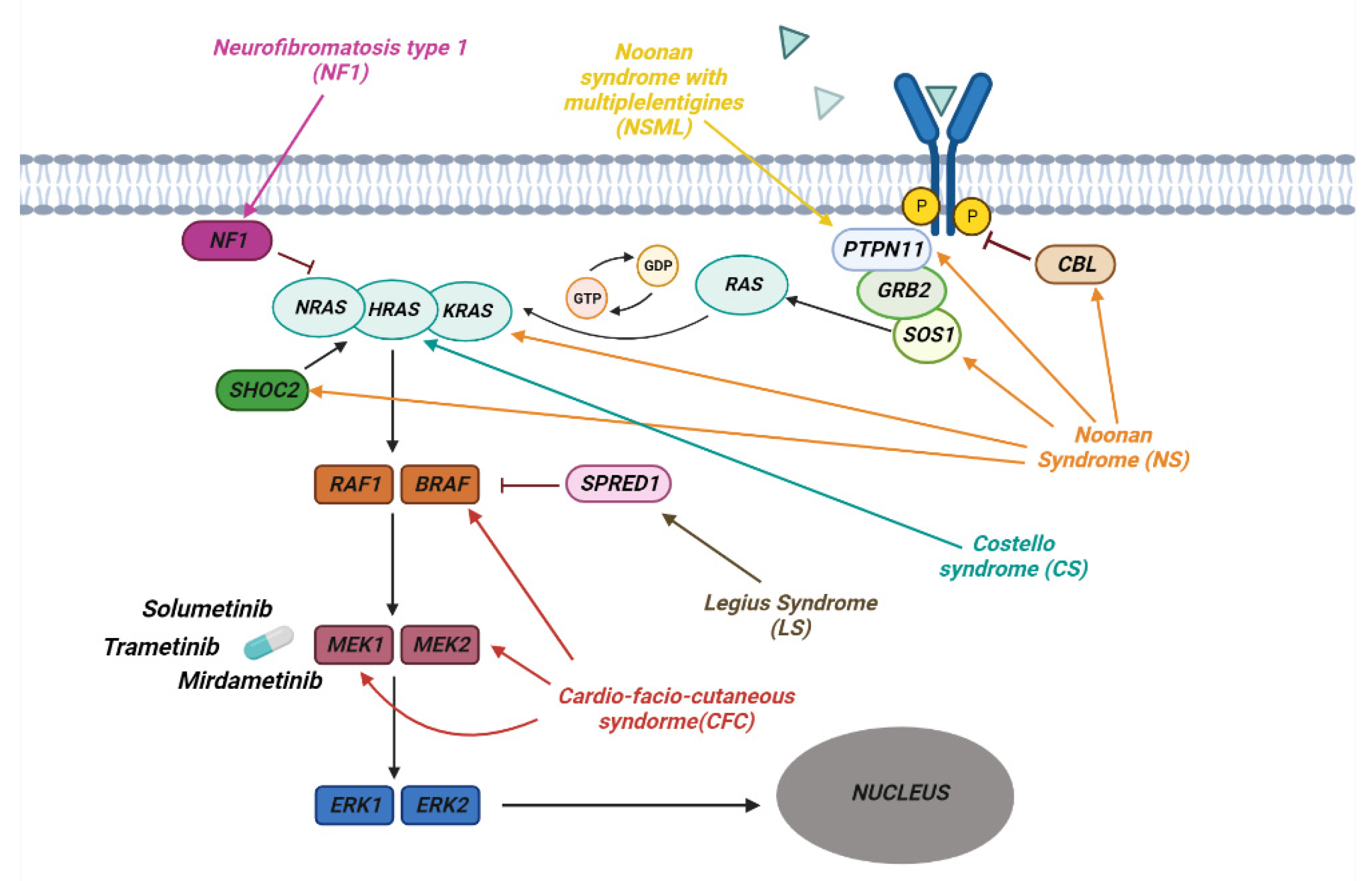

2. RASopathies

2.1. Clinical Manifestation

2.2. Neurofibromatosis

2.3. Noonan Syndrome

2.4. Genetics of RASopathies

2.5. Inibition of RAS Downstream Targets

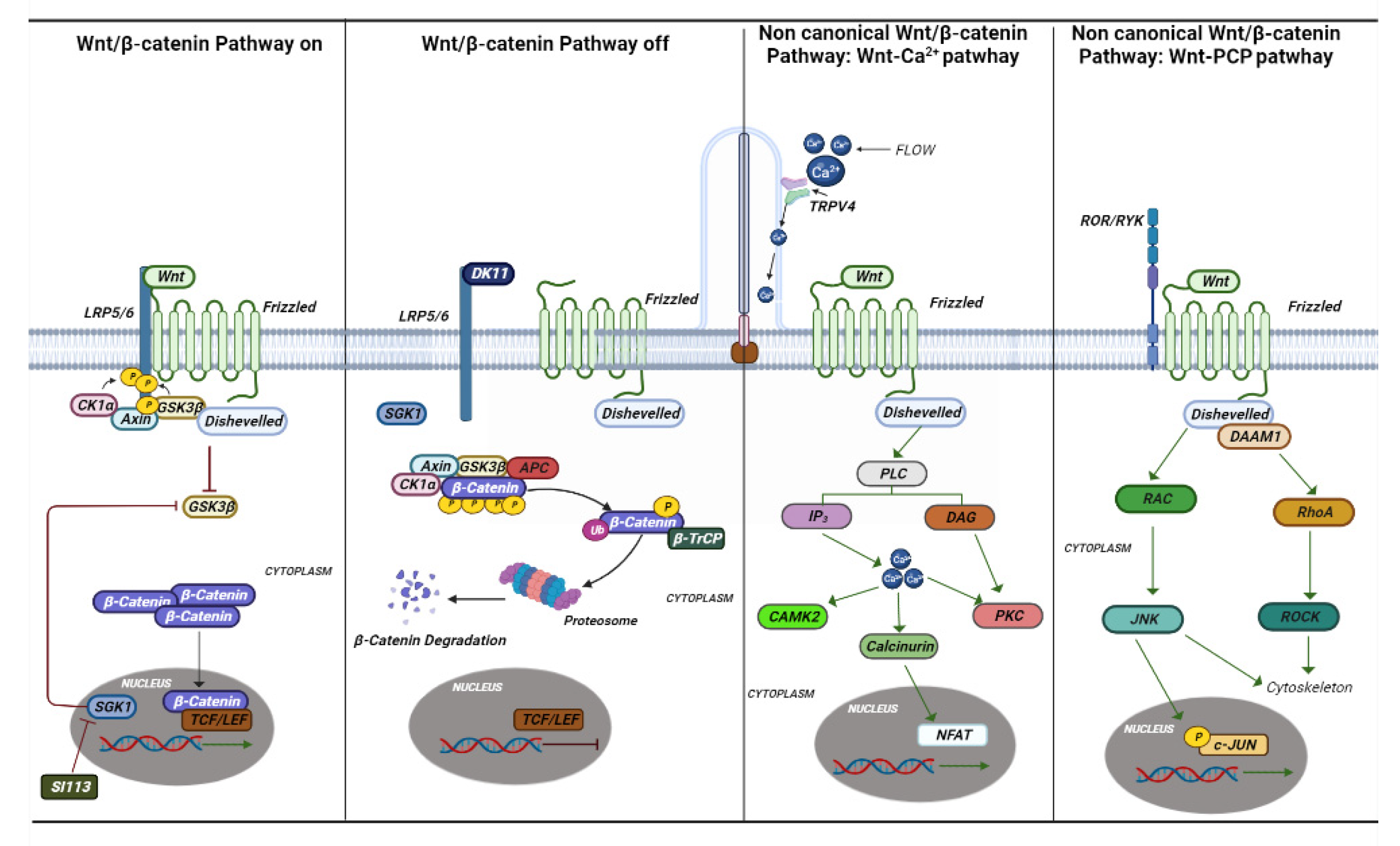

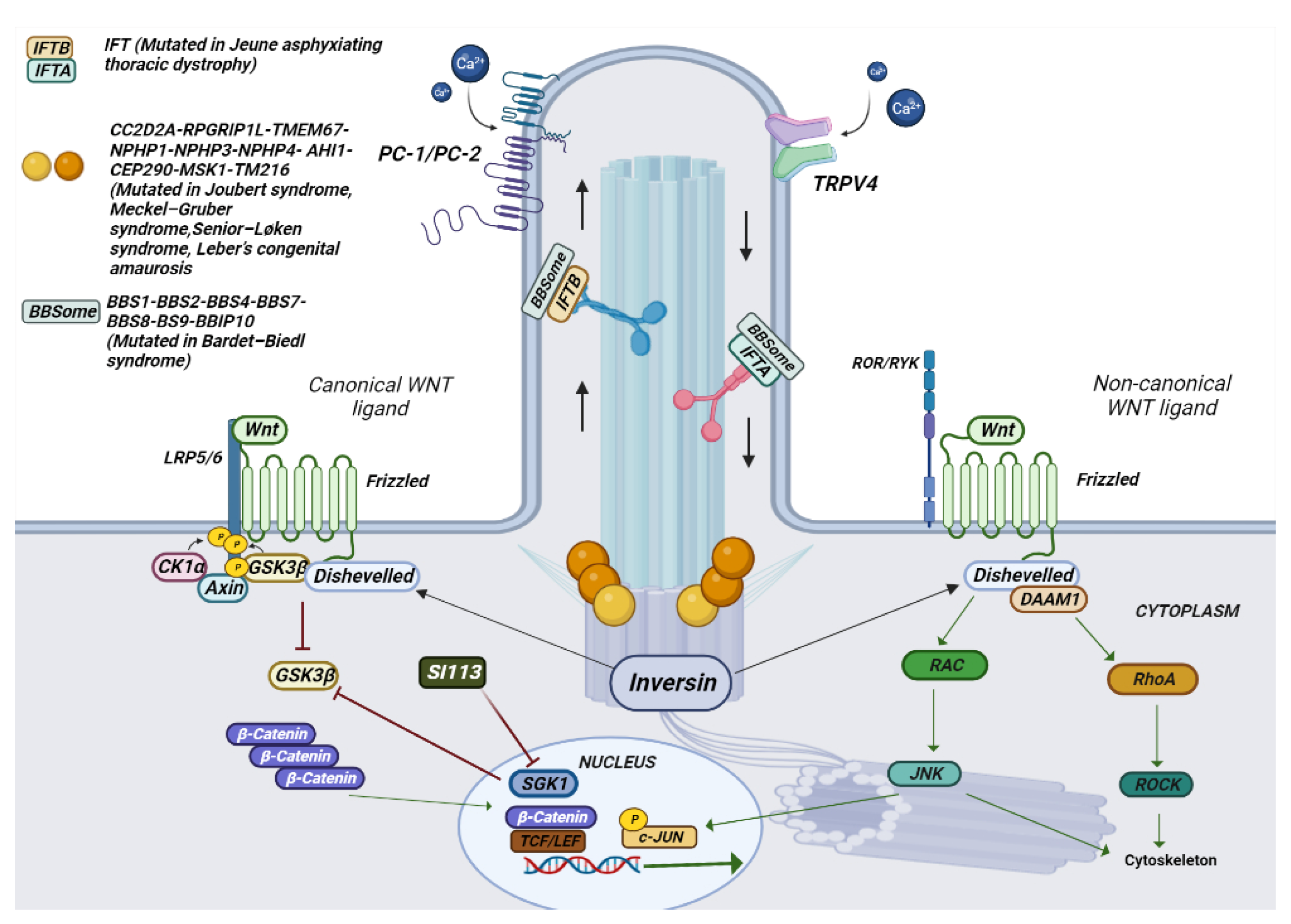

3. Ciliopathies

3.1. Clinical Manifestation

3.2. The Genetics of Ciliopathies

3.3. Inibition of TRPV4 and SGK1

References

- Osborne, J.P.; Fryer, A.; Webb, D. Epidemiology of Tuberous Sclerosis. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 1991, 615, 125–127.

- Curatolo, P.; Bombardieri, R.; Jozwiak, S. Tuberous sclerosis. Lancet 2008, 372, 657–668.

- DiMario, F.J. Brain Abnormalities in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. J. Child Neurol. 2004, 19, 650–657.

- Luat, A.F.; Makki, M.; Chugani, H.T. Neuroimaging in tuberous sclerosis complex. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2007, 20, 142–150.

- Islam, M.P.; Roach, E.S. Tuberous sclerosis complex. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2015, 132, 97–109.

- Kaczorowska, M.; Jurkiewicz, E.; Domańska-Pakieła, D.; Syczewska, M.; Lojszczyk, B.; Chmielewski, D.; Kotulska, K.; Kuczyński, D.; Kmieć, T.; Dunin-Wąsowicz, D.; et al. Cerebral tuber count and its impact on mental outcome of patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsia 2011, 52, 22–27.

- Capal, J.K.; Bernardino-Cuesta, B.; Horn, P.S.; Murray, D.; Byars, A.W.; Bing, N.M.; Kent, B.; Pearson, D.A.; Sahin, M.; Krueger, D.A. Influence of seizures on early development in tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsy Behav. 2017, 70, 245–252.

- Jansen, F.E.; Vincken, K.L.; Algra, A.; Anbeek, P.; Braams, O.; Nellist, M.; Zonnenberg, B.A.; Jennekens-Schinkel, A.; Ouweland, A.V.D.; Halley, D.; et al. Cognitive impairment in tuberous sclerosis complex is a multifactorial condition. Neurology 2007, 70, 916–923.

- Ehninger, D.; Sano, Y.; De Vries, P.J.; Dies, K.; Franz, D.; Geschwind, D.H.; Kaur, M.; Lee, Y.-S.; Li, W.; Lowe, J.K.; et al. Gestational immune activation and Tsc2 haploinsufficiency cooperate to disrupt fetal survival and may perturb social behavior in adult mice. Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 17, 62–70.

- Wu, S.; Wu, F.; Jiang, Z. Identification of hub genes, key miRNAs and potential molecular mechanisms of colorectal cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 2043–2050.

- Van Slegtenhorst, M.; de Hoogt, R.; Hermans, C.; Nellist, M.; Janssen, B.; Verhoef, S.; Lindhout, D.; van den Ouweland, A.; Halley, D.; Young, J.; et al. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science 1997, 277, 805–808.

- Sancak, O.; Nellist, M.; Goedbloed, M.; Elfferich, P.; Wouters, C.; Maat-Kievit, A.; Zonnenberg, B.; Verhoef, S.; Halley, D.; Ouweland, A.V.D. Mutational analysis of the TSC1 and TSC2 genes in a diagnostic setting: Genotype—Phenotype correlations and comparison of diagnostic DNA techniques in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2005, 13, 731–741.

- Cheadle, J.P.; Reeve, M.P.; Sampson, J.R.; Kwiatkowski, D.J. Molecular genetic advances in tuberous sclerosis. Hum. Genet. 2000, 107, 97–114.

- Kwiatkowski, D.J.; Manning, B.D. Molecular Basis of Giant Cells in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 778–780.

- Dibble, C.C.; Cantley, L.C. Regulation of mTORC1 by PI3K signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 545–555.

- Tee, A.R.; Fingar, D.C.; Manning, B.D.; Kwiatkowski, D.J.; Cantley, L.C.; Blenis, J. Tuberous sclerosis complex-1 and -2 gene products function together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated downstream signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 13571–13576.

- Crino, P.B. mTOR: A pathogenic signaling pathway in developmental brain malformations. Trends Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 734–742.

- Crino, P.B.; Nathanson, K.L.; Henske, E.P. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1345–1356.

- Huang, J.; Manning, B.D. The TSC1–TSC2 complex: A molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem. J. 2008, 412, 179–190.

- Ma, L.; Chen, Z.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Pandolfi, P.P. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell 2005, 121, 179–193.

- Carson, R.P.; Fu, C.; Winzenburger, P.; Ess, K.C. Deletion of Rictor in neural progenitor cells reveals contributions of mTORC2 signaling to tuberous sclerosis complex. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 22, 140–152.

- Vézina, C.; Kudelski, A.; Sehgal, S.N. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle. J. Antibiot. 1975, 28, 721–726.

- Franz, D.N.; Krueger, D.A. mTOR inhibitor therapy as a disease modifying therapy for tuberous sclerosis complex. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2018, 178, 365–373.

- Krueger, D.A.; Care, M.M.; Holland, K.; Agricola, K.; Tudor, C.; Mangeshkar, P.; Wilson, K.A.; Byars, A.; Sahmoud, T.; Franz, D.N. Everolimus for Subependymal Giant-Cell Astrocytomas in Tuberous Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1801–1811.

- Franz, D.N.; Belousova, E.; Sparagana, S.; Bebin, E.M.; Frost, M.; Kuperman, R.; Witt, O.; Kohrman, M.H.; Flamini, J.R.; Wu, J.Y.; et al. Everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: 2-year open-label extension of the randomised EXIST-1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 1513–1520.

- Rauen, K.A. The RASopathies. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2013, 14, 355–369.

- Bergqvist, C.; Network, N.F.; Servy, A.; Valeyrie-Allanore, L.; Ferkal, S.; Combemale, P.; Wolkenstein, P. Neurofibromatosis 1 French national guidelines based on an extensive literature review since 1966. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 37.

- Darrigo, L.G.; Geller, M.; Bonalumi Filho, A.; Azulay, D.R. Prevalence of plexiform neurofibroma in children and ado-lescents with type I neurofibromatosis. J. Pediatr. (Rio J.) 2007, 83, 571–573.

- Gross, A.M.; Singh, G.; Akshintala, S.; Baldwin, A.; Dombi, E.; Ukwuani, S.; Goodwin, A.; Liewehr, D.J.; Steinberg, S.M.; Widemann, B.C. Association of plexiform neurofibroma volume changes and development of clinical morbidities in neurofibromatosis 1. Neuro-Oncology 2018, 20, 1643–1651.

- Nguyen, R.; Kluwe, L.; Fuensterer, C.; Kentsch, M.; Friedrich, R.E.; Mautner, V.-F. Plexiform neurofibromas in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: Frequency and associated clinical deficits. J. Pediatr. 2011, 159, 652–655.e2.

- Weiss, B.; Bollag, G.; Shannon, K. Hyperactive Ras as a therapeutic target in neurofibromatosis type 1. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999, 89, 14–22.

- Tartaglia, M.; Zampino, G.; Gelb, B. Noonan Syndrome: Clinical Aspects and Molecular Pathogenesis. Mol. Syndr. 2010, 1, 2–26.

- Tartaglia, M.; Mehler, E.L.; Goldberg, R.; Zampino, G.; Brunner, H.G.; Kremer, H.; Van Der Burgt, I.; Crosby, A.H.; Ion, A.; Jeffery, S.; et al. Mutations in PTPN11, encoding the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2, cause Noonan syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2001, 29, 465–468.

- Matozaki, T.; Murata, Y.; Saito, Y.; Okazawa, H.; Ohnishi, H. Protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2: A proto-oncogene product that promotes Ras activation. Cancer Sci. 2009, 100, 1786–1793.

- Quilliam, L.A.; Rebhun, J.F.; Castro, A.F. A growing family of guanine nucleotide exchange factors is responsible for activation of ras-family GTPases. In Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; Volume 71, pp. 391–444.

- Tartaglia, M.; Pennacchio, L.; Zhao, C.; Yadav, K.K.; Fodale, V.; Sarkozy, A.; Pandit, B.; Oishi, K.; Martinelli, S.; Schackwitz, W.; et al. Gain-of-function SOS1 mutations cause a distinctive form of Noonan syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2006, 39, 75–79.

- Gremer, L.; Merbitz-Zahradnik, T.; Dvorsky, R.; Cirstea, I.C.; Kratz, C.P.; Zenker, M.; Wittinghofer, A.; Ahmadian, M.R. Germline KRAS mutations cause aberrant biochemical and physical properties leading to developmental disorders. Hum. Mutat. 2010, 32, 33–43.

- Schubbert, S.; Bollag, G.; Lyubynska, N.; Nguyen, H.; Kratz, C.P.; Zenker, M.; Niemeyer, C.M.; Molven, A.; Shannon, K. Bi-ochemical and Functional Characterization of Germ Line KRAS Mutations. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 7765–7770.

- Pandit, B.; Sarkozy, A.; Pennacchio, L.A.; Carta, C.; Oishi, K.; Martinelli, S.; Pogna, E.A.; Schackwitz, W.; Ustaszewska, A.; Landstrom, A.; et al. Gain-of-function RAF1 mutations cause Noonan and LEOPARD syndromes with hypertrophic cardiomyo-pathy. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 1007–1012.

- Mutation Analysis of the SHOC2 Gene in Noonan-Like Syndrome and in Hematologic Malignancies|Journal of Human Ge-netics. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/jhg2010116 (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Martinelli, S.; De Luca, A.; Stellacci, E.; Rossi, C.; Checquolo, S.; Lepri, F.; Caputo, V.; Silvano, M.; Buscherini, F.; Consoli, F.; et al. Heterozygous Germline Mutations in the CBL Tumor-Suppressor Gene Cause a Noonan Syndrome-like Phenotype. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 87, 250–257.

- Gripp, K.W.; Morse, L.A.; Axelrad, M.; Chatfield, K.C.; Chidekel, A.; Dobyns, W.; Doyle, D.; Kerr, B.; Lin, A.E.; Schwartz, D.D.; et al. Costello syn-drome: Clinical phenotype, genotype, and management guidelines. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2019, 179, 1725–1744.

- Zenker, M. Noonan Syndrome and Related Disorders: A Matter of Deregulated Ras Signaling; Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers: Basel, Switzerland, 2009.

- Nava, C.; Hanna, N.; Michot, C.; Pereira, S.; Pouvreau, N.; Niihori, T.; Aoki, Y.; Matsubara, Y.; Arveiler, B.; Lacombe, D.; et al. Cardio-facio-cutaneous and Noonan syndromes due to mutations in the RAS/MAPK signalling pathway: Genotype phenotype relationships and overlap with Costello syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2007, 44, 763–771.

- Ordan, M.; Pallara, C.; Maik-Rachline, G.; Hanoch, T.; Gervasio, F.L.; Glaser, F.; Fernandez-Recio, J.; Seger, R. Intrinsically active MEK variants are differentially regulated by proteinases and phosphatases. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11830.

- Widemann, B.C.; Babovic-Vuksanovic, D.; Dombi, E.; Wolters, P.L.; Goldman, S.; Martin, S.; Goodwin, A.; Goodspeed, W.; Kieran, M.W.; Cohen, B.; et al. Phase II trial of pirfenidone in children and young adults with neurofibromatosis type 1 and progressive plexiform neurofibromas. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2014, 61, 1598–1602.

- Widemann, B.C.; Salzer, W.L.; Arceci, R.J.; Blaney, S.M.; Fox, E.; End, D.; Gillespie, A.; Whitcomb, P.; Palumbo, J.S.; Pitney, A.; et al. Phase I Trial and Pharmacokinetic Study of the Farnesyltransferase Inhibitor Tipifarnib in Children With Refractory Solid Tumors or Neurofibromatosis Type I and Plexiform Neurofibromas. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 507–516.

- Widemann, B.C.; Dombi, E.; Gillespie, A.; Wolters, P.L.; Belasco, J.; Goldman, S.; Korf, B.R.; Solomon, J.; Martin, S.; Salzer, W.; et al. Phase 2 ran-domized, flexible crossover, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of the farnesyltransferase inhibitor tipi-farnib in children and young adults with neurofibromatosis type 1 and progressive plexiform neurofibromas. Neuro Oncol. 2014, 16, 707–718.

- Weiss, B.; Widemann, B.C.; Wolters, P.; Dombi, E.; Vinks, A.; Cantor, A.; Perentesis, J.; Schorry, E.; Ullrich, N.; Gutmann, D.H.; et al. Sirolimus for progressive neurofibromatosis type 1-associated plexiform neurofibromas: A Neurofibromatosis Clinical Trials Consortium phase II study. Neuro-Oncology 2014, 17, 596–603.

- Weiss, B.; Widemann, B.C.; Wolters, P.; Dombi, E.; Vinks, A.A.; Cantor, A.; Korf, B.; Perentesis, J.; Gutmann, D.H.; Schorry, E.; et al. Sirolimus for non-progressive NF1-associated plexiform neurofibromas: An NF clinical trials consortium phase II study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2013, 61, 982–986.

- Jakacki, R.I.; Dombi, E.; Potter, D.M.; Goldman, S.; Allen, J.C.; Pollack, I.F.; Widemann, B.C. Phase I trial of pegylated interferon- -2b in young patients with plexiform neurofibromas. Neurology 2011, 76, 265–272.

- Jakacki, R.I.; Dombi, E.; Steinberg, S.M.; Goldman, S.; Kieran, M.W.; Ullrich, N.J.; Pollack, I.F.; Goodwin, A.; Manley, P.E.; Fangusaro, J.; et al. Phase II trial of pegylated interferon alfa-2b in young patients with neu-rofibromatosis type 1 and unresectable plexiform neurofibromas. Neuro Oncol. 2017, 19, 289–297.

- Robertson, K.A.; Nalepa, G.; Yang, F.-C.; Bowers, D.C.; Ho, C.Y.; Hutchins, G.D.; Croop, J.M.; Vik, T.A.; Denne, S.C.; Parada, L.F.; et al. Imatinib mesylate for plexiform neurofibromas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1: A phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 1218–1224.

- Banerjee, A.; Jakacki, R.I.; Onar-Thomas, A.; Wu, S.; Nicolaides, T.; Poussaint, T.Y.; Fangusaro, J.; Phillips, J.; Perry, A.; Turner, D.; et al. A phase I trial of the MEK inhibitor selumetinib (AZD6244) in pediatric patients with recurrent or refractory low-grade glioma: A Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium (PBTC) study. Neuro-Oncology 2017, 19, 1135–1144.

- Dombi, E.; Baldwin, A.; Marcus, L.J.; Fisher, M.J.; Weiss, B.; Kim, A.; Whitcomb, P.; Martin, S.; Aschbacher-Smith, L.E.; Rizvi, T.A.; et al. Activity of Selumetinib in Neurofibromatosis Type 1–Related Plexiform Neurofibromas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2550–2560.

- Gross, A.; Bishop, R.; Widemann, B.C. Selumetinib in Plexiform Neurofibromas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1195.

- Plotkin, S.R.; Blakeley, J.O.; Dombi, E.; Fisher, M.J.; Hanemann, C.O.; Walsh, K.; Wolters, P.L.; Widemann, B.C. Achieving consensus for clinical trials: The REiNS International Collaboration. Neurology 2013, 81, S1–S5.

- McCowage, G.B.; Mueller, S.; Pratilas, C.A.; Hargrave, D.R.; Moertel, C.L.; Whitlock, J.; Fox, E.; Hingorani, P.; Russo, M.W.; Dasgupta, K.; et al. Trametinib in pediatric patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1)–associated plexiform neurofibroma: A phase I/IIa study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 10504.

- Waters, A.M.; Beales, P.L. Ciliopathies: An expanding disease spectrum. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2011, 26, 1039–1056.

- Oud, M.M.; Lamers, I.J.C.; Arts, H.H. Ciliopathies: Genetics in Pediatric Medicine. J. Pediatr. Genet. 2016, 6, 018–029.

- Khayyeri, H.; Barreto, S.; Lacroix, D. Primary cilia mechanics affects cell mechanosensation: A computational study. J. Theor. Biol. 2015, 379, 38–46.

- Sonkusare, S.K.; Bonev, A.D.; Ledoux, J.; Liedtke, W.; Kotlikoff, M.I.; Heppner, T.J.; Hill-Eubanks, D.C.; Nelson, M.T. Elementary Ca2+ Signals Through Endothelial TRPV4 Channels Regulate Vascular Function. Science 2012, 336, 597–601.

- Feather, S.A.; Winyard, P.J.; Dodd, S.; Woolf, A. Oral-facial-digital syndrome type 1 is another dominant polycystic kidney disease: Clinical, radiological and histopathological features of a new kindred. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1997, 12, 1354–1361.

- Beales, P.L.; Elcioglu, N.; Woolf, A.S.; Parker, D.; Flinter, F.A. New criteria for improved diagnosis of Bardet-Biedl syn-drome: Results of a population survey. J. Med. Genet. 1999, 36, 437–446.

- Tobin, J.L.; Di Franco, M.; Eichers, E.; May-Simera, H.; Garcia, M.; Yan, J.; Quinlan, R.; Justice, M.J.; Hennekam, R.C.; Briscoe, J.; et al. Inhibition of neural crest migration underlies craniofacial dysmorphology and Hirschsprung’s disease in Bardet–Biedl syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 6714–6719.

- He, X.; Semenov, M.; Tamai, K.; Zeng, X. LDL receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: Arrows point the way. Development 2004, 131, 1663–1677.

- Habas, R.; Dawid, I.B. Dishevelled and Wnt signaling: Is the nucleus the final frontier? J. Biol. 2005, 4, 2.

- LeCarpentier, Y.; Schussler, O.; Hébert, J.-L.; Vallée, A. Multiple Targets of the Canonical WNT/β-Catenin Signaling in Cancers. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1248.

- Bian, J.; Dannappel, M.; Wan, C.; Firestein, R. Transcriptional Regulation of Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway in Colorectal Cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 2125.

- Abdelhamed, Z.A.; Abdelmottaleb, D.I.; El-Asrag, M.E.; Natarajan, S.; Wheway, G.; Inglehearn, C.F.; Toomes, C.; Johnson, C.A. The ciliary Frizzled-like receptor Tmem67 regulates canonical Wnt/β-catenin signalling in the developing cerebellum via Hoxb5. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5446.

- Brancati, F.; Italy, U.D.N.; Camerota, L.; Colao, E.; Vega-Warner, V.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, R.; Bottillo, I.; Castori, M.; Caglioti, A.; et al. Biallelic variants in the ciliary gene TMEM67 cause RHYNS syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 26, 1266–1271.

- Abdelhamed, Z.A.; Wheway, G.; Szymanska, K.; Natarajan, S.; Toomes, C.; Inglehearn, C.; Johnson, C.A. Variable expressivity of ciliopathy neurological phenotypes that encompass Meckel-Gruber syn-drome and Joubert syndrome is caused by complex de-regulated ciliogenesis, Shh and Wnt signalling defects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 1358–1372.

- Bagher, P.; Beleznai, T.; Kansui, Y.; Mitchell, R.; Garland, C.J.; Dora, K.A. Low intravascular pressure activates endothelial cell TRPV4 channels, local Ca 2+ events, and IK Ca channels, reducing arteriolar tone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 18174–18179.

- Preston, D.; Simpson, S.; Halm, D.; Hochstetler, A.; Schwerk, C.; Schroten, H.; Blazer-Yost, B.L. Activation of TRPV4 stimulates transepithelial ion flux in a porcine choroid plexus cell line. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2018, 315, C357–C366.

- Hochstetler, A.E.; Smith, H.M.; Preston, D.C.; Reed, M.M.; Territo, P.R.; Shim, J.W.; Fulkerson, D.; Blazer-Yost, B.L. TRPV4 antagonists ameliorate ventriculomegaly in a rat model of hydrocephalus. JCI Insight 2020, 5, 137646.