| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prakash B Adhikari | -- | 5946 | 2023-03-03 10:34:23 | | | |

| 2 | Prakash B Adhikari | -608 word(s) | 5338 | 2023-03-03 11:17:43 | | | | |

| 3 | Rita Xu | -49 word(s) | 5289 | 2023-03-08 03:35:45 | | |

Video Upload Options

1. Introduction

2. Grafting-derived novelty

3. Grafting Skill

4. Choice of Graft Partners

5. Requirements of Graft Establishment

5.1. Wounding

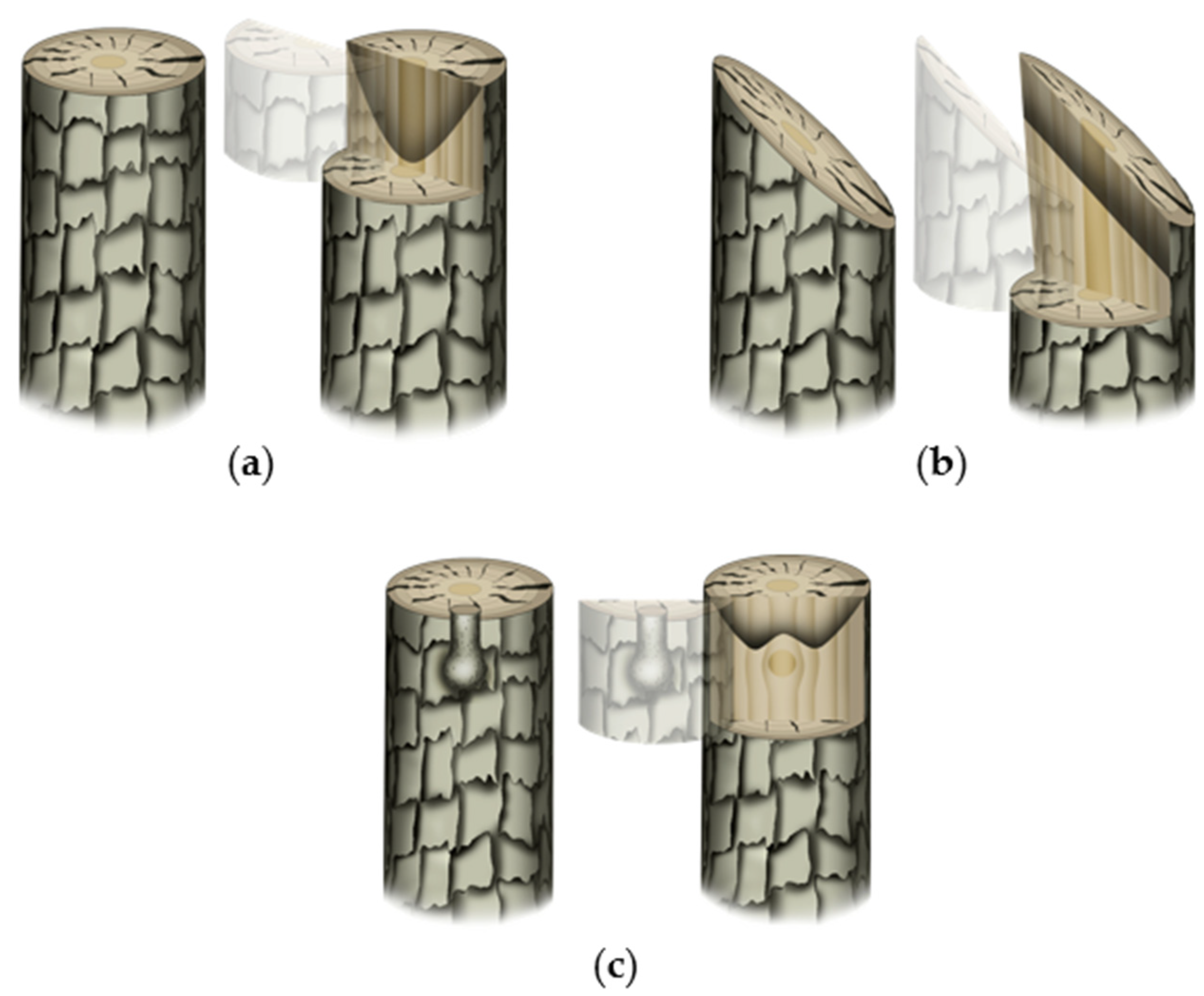

Wounding response is an essential first step in mechanical grafting. Observational studies in woody plants showed that, under an open and uncontrolled environment, the tree response to wound varies by the time in a year. Swarbrick [43] meticulously classified the wound response of several woody species into three distinct categories based on his year-round observations (in England). An interesting observation of the study was that the pith is clogged up relatively early during the healing process assisted by the callose deposition [44]. However, the blocking (clogging) patterns of the stem were found to vary with the type and site of wounding (Figure 2). A horizontal cut leads to clogging up of the pith followed by side tissues (Figure 2a). When the stem was wounded at an oblique angle, the clogging at the cut surface occurred obliquely as well (Figure 2b). The clogging-up of the wounded stem close to a living branch, on the other hand, depends on its emergence (Figure 2c). Such blockage is crucial to prevent the potential leakage of resources and the entry of pathogens. While the wound response of the tree can be comparable to the graft wound (rootstock in particular), the major difference would be that the wound is not left exposed in grafting (at least at the graft junction). Since plant cells are totipotent in nature, the ‘instinctive’ wounding cue of the top plant part (scion in the grafting sense) is expected to either grow fresh roots or attach to the tissues of compatible host/rootstock. The bottom part (rootstock in the grafting sense), on the other hand, either needs to clog up the wound and/or, if the above cut surface is accessible, reconnect tissues otherwise grow new lateral branches. Such an assumption is partly corroborated by some of the relevant studies in the field. Girdling, which essentially disconnects phloem in a stem, is known to enhance the rooting potential of the cuttings in woody plants by increasing the carbohydrates, polyamines, and phenolic compounds' statuses in it [45][46][47]. The interruption of basipetal IAA (indole acetic acid; an auxin member) movement (and its overaccumulation at the scion) is reportedly one of the known causes behind such a phenomenon [48]. In another case, top part removal or bud excision essentially removes the apical auxin synthesis part and top-to-bottom auxin flow thereby relieving the plant of the repressive effect on lateral branching caused by the apical dominance [49][50].

Figure 2. Typical wound-induced clogging up pattern in trees. The first and second images in each sub-figure represent wounding type/condition and virtual sectioning (for better visualization of the clogging patterns), respectively: (a) clean horizontal cut leads to clogging up of pith followed by side-by tissues; (b) oblique cut leads to the formation of the clogged-up barrier in parallelly oblique position; and (c) when there is a branch present beneath the cut surface, the clogging up occurs in such a way that the nutrient and metabolite flow to and from the branch would not be hindered.

5.2. Mechanical Adhesion

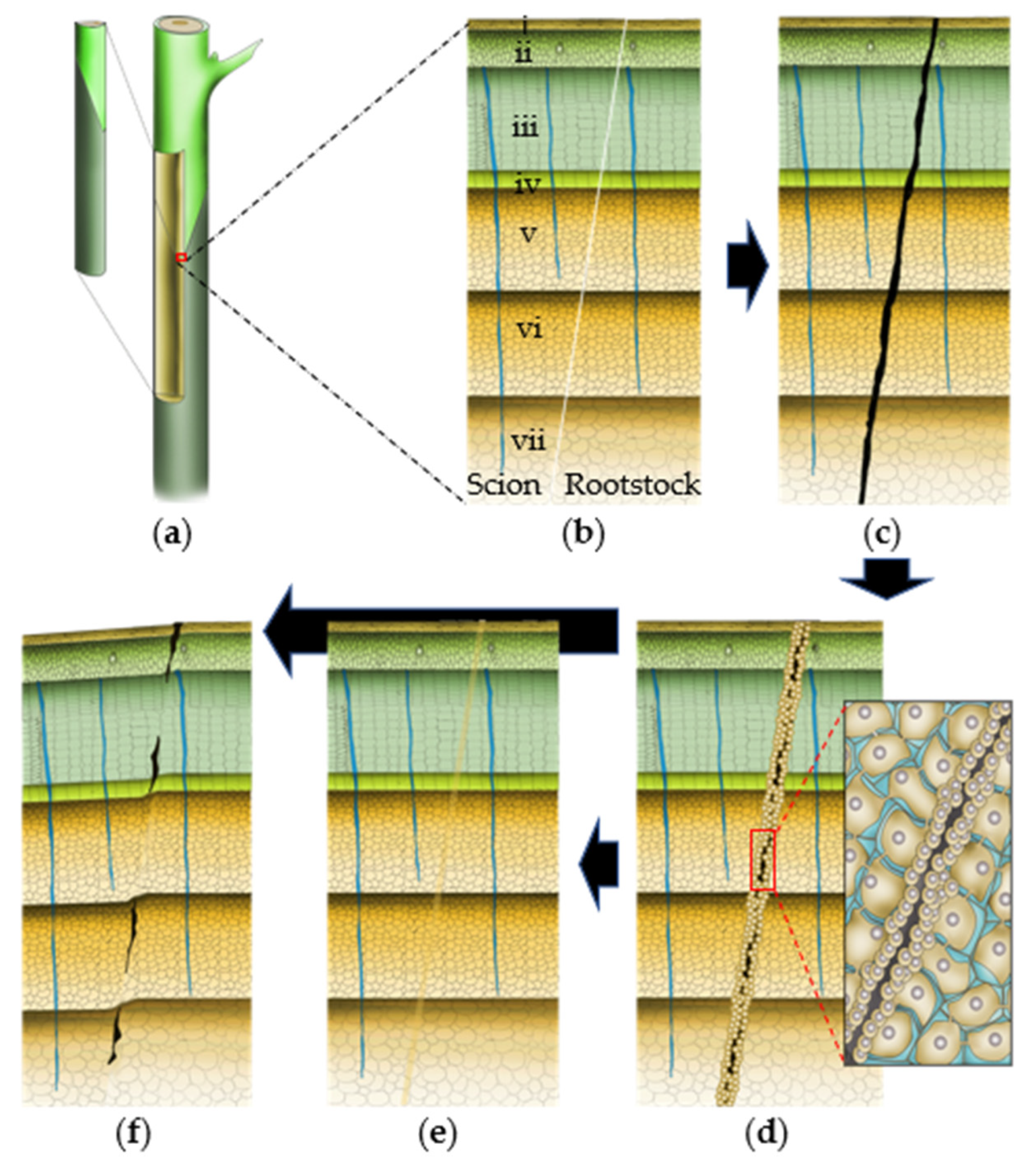

Wounding-induced callus formation graft surgery needs to be preceded by the adhesion of two graft-partner surfaces to progress toward compatible union formation (Figure 3, Table 1). Studies have shown that pectin plays a crucial role during this step. An observational study in Solanaceous plants showed that pectinaceous materials at the graft interface are crucial for the establishment of initial ‘mechanical union’ [51]. Moreover, as observed among solanaceous plants, the tissue adjoining is initiated at the center (pith) of all graft combinations after a few hours of assemblage, which expands laterally afterward. However, such initial adhesion at the graft surface does not necessarily guarantee the success of graft establishment/graft compatibility, unless a functional vascular connection is established between the graft partners later on [35][51]. The pectinaceous materials get incorporated into a common wall complex at the graft junction, which thickens for up to 4 days after grafting in herbaceous plants (tomato in particular) due to the polymerization of the secreted wall precursors [35]. Such initial adhesion seems to be further strengthened by the resins excessively secreted by some plants like mango [33]. Anatomical observations made during the very early stages of graft establishment in herbaceous plants have shown the accumulation of dictyosomes along the cell walls of the unwounded cells adjacent to the necrotic layer suggesting their potential role in the pectinaceous material (pectin, carbohydrate, suberin, etc.) secretion [52][53]. Such secretions, along with the wounded cell debris, contribute to the necrotic layer formation, which disintegrates after callus proliferation in compatible graft combinations [54]. A successful graft establishment requires swift rupture of the necrotic layer probably following yet unidentified cues of tissue joining compatibility at the graft junction. An incompatible graft junction, however, often exhibits an ‘ever-thickening’ necrotic layer at the junction [52][55].

Figure 3. Basic anatomical states of graft establishment. (a–f) Typical transverse sections at the progressively healing graft union: (a) mechanically attached scion-rootstock combination with virtual sectioning at the graft joint; (b–f) magnified structure of a typical transverse section at the progressively healing graft union; (b) freshly attached scion and rootstock; (c) pectinaceous materials are secreted at the graft union and the attached graft partner surfaces are mechanically attached; the secreted pectinaceous materials, along with the cell debris forms a necrotic layer at the graft interface; (d) wound signal perception leads to the callus production at the graft interface, which thins out the necrotic barrier leading to the establishment of a callus bridge between two graft partners. The magnified image shows the proliferating callus cells before callus bridge formation at the graft interface; (e) a seamless connection is established at a compatible graft union; and (f) partially compatible graft unions often exhibit the remnants of the necrotic layer and/or aberrant vascular continuity. In severe incompatibility cases, the necrotic layer never disintegrates at all. i = cork and epidermis ii = cortex; iii = phloem; iv = vascular cambium; v = xylem; vi = protoxylem; vii = pith.

Although there has not been any direct link between the upregulation of pectin biosynthesis-related genes and graft compatibility, several studies have reported changes in the expression of the genes encoding cell wall modifying enzymes [37][56]. However, the studies indicate that those enzymes contribute to the post-callus-proliferation cell-cell adhesion process instead of the initial mechanical adhesion of the graft partners. Alternatively, since pectin is localized at the middle lamella, its initial and almost immediate secretion at the wounding site could be due to the mechanical pressure of intact cells juxtaposed interior to the damaged cells.

A recent study in Arabidopsis by Zhang, et al. [57] showed that changes in cellulose or pectin matrices are sufficient to activate wound response thereby triggering callus formation. The study further observed the activation of four particular DOF (DNA binding with one finger) related transcription factors at the graft junction, which play role in post-wounding callus formation, pectin methylesterification, tissue adhesion, and vascular differentiation in plants. Earlier studies have additionally reported that members of wound-inducible wall-associated kinases (WAKs, WAK1, and WAK2 in particular) harbor N-terminal extracellular domain with binding affinity to pectin essentially serving as pectin receptors (reviewed by [58]), indicating that plant cells ‘sense’ extracellular pectin status and trigger wound response upon any abrupt changes. Though the mechanics are yet poorly understood, the pectin-rich middle-lamella alters throughout the plant lifecycle and is apparently tightly regulated during the process (for details, check [59][60]). The accumulation of pectin at the graft junction is quintessential during early stage of graft establishment. However, its thick layer needs to be dissipated and plasmodesmatal connections need to be established between the cells at the junction for a compatible graft union [51][61]. Relatively recent studies in Prunus spp. have also shown that pectin (and insoluble carbohydrates) deposition at the graft junction within a week after grafting is common for both compatible and incompatible graft unions. However, the level of pectin gradually decreases with cell differentiation (vascularization of the dedifferentiated callus) in compatible combinations, while it tends to remain at least at the same level in incompatible ones [62][63]. Interestingly, a hypocotyl grafting study in tomato has revealed that the wound response triggered due to the initial severance of the graft partners is gradually subdued. Furthermore, unlike the incompatible union, a compatible combination alleviates the asymmetry of wound-responsive elements between the graft partners [64]. The study showed differential contents of jasmonic acid (JA) and its isoleucine conjugate (JA-Ile) in the non-grafted scion and rootstock plant parts with the former having higher contents of both as compared to the latter. The trend of JA and JA-Ile content was opposite during the 12-hr window after grafting. While the JA content was the lowest at the beginning and end, that of JA-Ile was highest during those times.

5.3. Callus-Bridge formation

Callus, a mass of parenchymatous cells, is also referred to as ‘wound tissue’ as it is essentially triggered at any wounded plant tissue. Its formation is initiated from the cambial cells at the cortex of the graft partners, (often) rapid proliferation of which fills in empty space between the scion and rootstock interface [11][54][65]. However, callus proliferation and gap-filling alone do not facilitate the metabolite and nutrient flow across the graft junction [66]. Interestingly, observations show that woody species initiated callus proliferation relatively earlier at their rootstock interface as compared to that in their scion counterparts as reported in in vitro micrografted four-week-old kiwifruits [65] and ex vitro propagated six-week-old mango seedlings [33] at three days after grafting. However, studies in herbaceous plants show that the case could be the opposite in them. As observed in Arabidopsis, the scion interface exhibits higher cellular proliferation as compared to the rootstock interface at least two days after grafting, which subsides to nonsignificant by three days of grafting [67]. Furthermore, an interesting observation in the mango grafting study suggested that callus cells are prone to divide periclinally with respect to the incised surface at the graft junction forming a ‘fan-shaped’ callus region with the fresher cells proliferating vertically and their older progenitor cells proliferating laterally [33].

Callus proliferation followed by the callus bridge formation between the graft partners is necessary and is an initial sign of graft compatibility, which unlike in herbaceous plants, may take weeks in woody counterparts [31][66]. During this stage, the proliferating calli (generally from both graft-partners) invade and rupture the necrotic layers thereby coming in contact with the cells from the graft-partner and sharing a common cell wall during the bridge formation [31][68]. It is quintessential for the proliferating callus cells of opposite graft partners to come to close proximity for the bridge establishment. However, whether cellular recognition plays any role in the process is still being debated. Movement/absorption of putative protein molecules secreted by the cells of opposite graft-partner at the junction and hence forming a macromolecular complex potentially involving molecules like glycoprotein receptors and lectins had been proposed to be a prerequisite for a graft establishment. Such postulation has been made based on the report that graft unions synthesize additional proteins that are not synthesized at the non-grafted wounds [35][51]. Such a report has been corroborated by more recent transcriptomic studies in the herbaceous model as well, which showed that unlike in non-grafted graft partners, grafted ones exhibited vascular formation-related gene expression [69]. However, while it cannot be completely ruled out, no specific molecule playing a direct role in cellular recognition has been identified to this date, even though the host-parasite joint establishment by mistletoes has been suggested to employ lectin I during the process [70][71][72]. Alternatively, Moore [73] strongly argued that a specific cellular recognition process would not be necessary during graft union formation. He demonstrated that compatible grafting partners still exhibit vascular redifferentiation at the graft junction even when they are separated by a porous membrane filter which hindered direct cellular contact but allowed the flow of diffusible messenger compounds. Regardless of whether cellular recognition is involved in the process or not, studies in herbaceous models have shown that the cells at the site of incision undergo only mild senescence in compatible grafts, but, in the incompatible combinations, those go beyond the lethal stage and proliferated callus, that is a coincidental result of wounding, do not rupture the necrotic layer [52][55].

6. Factors behind Graft Compatibility

6.1. Compartmentalization Efficiency

Walling off the injured and/or infected region from the healthy tissue is essential for the avoidance of pathogen infection after wounding. In trees, the phenomenon of compartmentalizing the wounded region made by biotic and abiotic reasons has often been explained using CODIT model (Compartmentalization of Damage/Dysfunction in Trees) [74][75]. The model suggests the roles of four protective boundary-setting conceptual walls formed before (walls 1–3) or after wounding (wall 4). Wall 1 plugs xylem vessels with tyloses or polyphenols, which impede the longitudinal spread of pathogenesis through the stem. Wall 2 comprises the woody annual rings and restricts the decay in radial directions through lignified fibers and polyphenolic compounds. Wall 3 (ray parenchyma) reduces the transverse expansion/fungal spread, while wall 4 (cambial wall or the barrier zone) separates the wounded/infected tissues from the new xylem laid down to the barrier zone’s exterior. Wall 4 is a lignified and suberized parenchymatous zone of phenolic compounds initiated by the cambium after wounding. In general, wall 4 is composed of multiple layers and functions as the strongest of all. Santamour [74] pointed out that the cultivars generally propagated via grafting/budding has strong wound compartmentalizers and postulated that the trees with weak compartmentalization capabilities may not even be successfully grafted onto themselves (autografting). With respect to the positive correlation between the strong wall 2 and graft compatibility, the author discussed that it may be because its build-up is correlated with the availability of starch, stored carbohydrates, in xylem parenchyma suggesting that the trees are more efficient on carbohydrate storage and utilization to develop stronger wall 2 could be better graft takers. More targeted studies in the future may shed more light on this aspect.

6.2. Cell Wall Modifications

Cell wall reconstruction plasticity plays a crucial role in compatible graft establishment. Studies have shown that cell wall modification is active [35][51] and associated genes are upregulated at the graft union during the graft healing process [56][57]. It is very likely that the species with a higher potential of upregulating cell wall modifying genes upon wounding are highly compatible to grafting. A relatively recent grafting compatibility study corroborates such an assumption [37]. The study reported that the cell wall reconstruction potential of plants may vary. Among several herbaceous and woody plants, Nicotiana was found to establish graft union with a wide range of plants. The authors attributed its potential to β-1,4-glucanases, particularly GH9B3, secreted into the extracellular region and involved in the cell wall reconstruction process near the graft interface [37].

6.3. Phytohormones

Auxin and cytokinin, at their varying proportions, regulate the cellular dedifferentiation and redifferentiation processes [76]. A recent study on Kinnow mandarin grafted on different citrus rootstocks reported a positive correlation between its vegetative growth and the levels of IAA, gibberellic acid (GA), and zeatin). Furthermore, dwarf and vigorous rootstocks had higher and lower levels of abscisic acid (ABA) [77]. ABA reduces the hydraulic conductivity of the rootstock [78] thereby conferring dwarf phenotype to the scion [79]. Dwarfing rootstocks often have a higher bark-to-wood (xylem) ratio, a trait suggested as a marker for selecting such rootstocks [14]. JA on the other hand acts in coordination with auxin and cytokinin, and positively affects cellular redifferentiation (xylem differentiation in particular). Studies show that graft unions are characterized by the asymmetry of hormone content between the graft partners, which unlike in incompatible combinations, gradually subsides in their compatible counterparts [64][80]. A recent comparative study in citrus showed increased ABA and reduced IAA contents in the incompatible citrus graft combination (‘Hongmiyou’ pomelo grafted on trifoliate orange) as compared to its compatible counterpart (‘Guanximiyou’ pomelo grafted on trifoliate orange). The study further associated such occurrences with the increase in starch accumulation and etiolation traits [81]. Such hormonal disparities and associated traits between the graft partners can be taken as graft-incompatibility indicators and should be considered while selecting compatible graft partners.

6.4. Photosynthate and Metabolites Translocation

In general, the early incompatible graft combinations often exhibit retarded growth of both shoot and root [7][8][9]. The growth of the graft partners is directly associated with the efficiency of photosynthate and metabolite flows across the graft junction. Graft incompatibility accompanying vascular discontinuity, called ‘localized’ incompatibility, results in breakage at the graft union. The ‘localized’ incompatibility has been characterized by graft union swelling, vascular discontinuities, and clear necrotic layer formation [30]. On the other hand, plants often exhibit a ‘translocated’ incompatibility response, which may take several years to exhibit [6][9]. Translocated incompatibility occurs when some causal factor(s), such as a toxin, is transported from one graft partner to the other. Some metabolites produced in some mature tissues can be toxic to partner plants [30]. Furthermore, the energy-rich state of the scion, often achieved via pre-girdling, is known to enhance graft compatibility [82] by providing the scion a longer time window for self-sustenance until the functional connection is established at the graft junction. Hindrances in the metabolite flow lead to the yellowing and reddening of the leaves/wood, defoliation, reduction in tree vigor, and senescence as reported in peach/plum [6] and grapes [12]. Furthermore, the growth rates of different species vary, which largely correlates with the efficiency of their hydraulic conductance [83]. Graft combination between the scion and rootstock exhibiting differential growth rate may result in ‘localized’ incompatibility [30]. Thus, various causes, including mechanical, anatomical, and physiological reasons, result in both early and delayed incompatibilities [10][84].

6.5. Polyphenols, Peroxidases, and Lignification

As also mentioned earlier, in the case of incompatible unions, the necrotic layer most often does not fully disintegrate, and instead becomes even more prominent during the latter time [52][55][84]. However, researchers need to be cautious while generalizing such observations because incompatible combinations may also purge the necrotic layers [7] and form callus as well as xylem and phloem tissues albeit to a lesser degree at certain conditions and seasons [7][9].

Phenolic compounds, particularly flavanols, are often credited for their crucial involvement in scion-rootstock relations [11]. Moing, et al. [7] earlier documented that, unlike compatible peach-plum combinations, their incompatible combinations are characterized by the prevalence/persistence of ‘osmophilic’ granulations near the plasmalemma of some sieve elements at the graft junction in later days of grafting. Zarrouk, et al. [9] additionally reported the prevalence of phenolic compounds in the cells at the junctions of incompatible peach/plum unions. Similar disparities in the polyphenol contents have also been made in cherry [85][86], apricot [87], and pear [88]. Such differences were positively correlated with the cellular degeneration and dysfunctional vascular connection assessed at the incompatible graft unions [9][89]. Anatomical observations have shown that the synthesis of polyphenolic compounds is negatively correlated with the lignification status of the graft union, i.e., phenolic compounds are synthesized at a higher level when the lignification process commences, which gradually decreases afterward in the compatible unions [86]. However, the duration of such disparities may vary with species [9][89].

The degeneration of the phloem sieve tubes and companion cells at the graft union of incompatible/late-incompatible unions often appears along with the higher levels of phenolic compounds accumulation at the site [5][9][55][73]. Phenolic compounds are also associated with graft union formation. Lignin, a polymer of phenolic compounds (particularly of coniferyl alcohol, sinapyl alcohol, and ρ-coumaric alcohol), is an important component for compatible graft establishment. Compatible unions often exhibit progressive cellular lignification beginning from the callus to the differentiated vascular tissues [31][90]. Peroxidase enzymes have been implicated for their involvement in the final step of lignin biosynthesis as well as in auxin degradation [91][92]. Histological observations have often indicated a correlation between the persistence of peroxidases and the increase of lignin [90]. The biosynthesis of the peroxidase enzyme itself is regulated by phenolic compounds [92]. The graft combination showing severe translocation defect exhibits higher peroxidase activity [9]. Cationic peroxidases, in particular, are considered more reliable markers of graft incompatibility. However, studies have suggested that the peroxidase group conferring graft incompatibility could be specific to particular combinations/species, as a study in castor bean found four extracellular cationic isoperoxidases as potential players of lignin biosynthesis [91] and studies in pear/quince [39] and in peach/plus grafting [9] have reported one each. A study on zucchini showed that in contrast to their cationic counterparts, anionic peroxidases are prevalent in the elongating cells and are negatively correlated with the lignin content [93]. A strong positive correlation has been observed between the cationic peroxidases and cellular lignification in poplar as well [94]. Studies show the parallelism between the graft-incompatibility-induced and incompatible-host-pathogen-induced cellular lignification [90][95] suggesting the involvement of similar molecular factors. It is very plausible but it requires further studies to conclude if the cationic peroxidase-induced lignification is the key factor behind the hindrance of cellular expansion/connection/exchange at the graft union.

Regarding polyphenols, a comparative study in several compatible and incompatible cherry graft combinations revealed prunin as the most prevalent polyphenol followed by chlorogenic acid and catechin in incompatible combinations. The study further showed that one of the incompatible combinations (Regina/Gisela) had high ρ-coumaric acid, which they attributed to its above-graft-joint-swelling as well as dwarfing phenotypes [86]. The prevalence of the compound in the dwarfing rootstocks and its association with early graft incompatibility has also been reported in cherry [96]. Similar observations have been made on less compatible/incompatible wild loquat in which higher contents of ρ-coumaric acid and flavonoids were identified [97] and chestnut in which higher contents of gallic acid and catechin were detected [98]. Another study in cherry showed that the autografts, homografts, and/or homogenic grafts often exhibit lower ρ-coumaric acid content as compared to heterografts/heterogenic grafts [86].

ρ-Coumaric acid can serve as a precursor of prunin, gallic acid, and catechin, and its conversion to prunin is enhanced under stress conditions. While the prunin enhances the oxidative decarboxylation of IAA, a hormone crucially important during graft establishment, ρ-coumaric acid reportedly functions as an IAA antagonist [99][100]. Furthermore, ρ-coumaric acid enhances the acropetal auxin transport and, unlike most other phenolic compounds, ρ-coumaric acid plays role in decreasing cell wall permeability [100]. Exogenous treatment of ρ-coumaric acid to an herbaceous plant, soybean, ameliorated H2O2 level but enhanced the cell wall-bound peroxidase activities and increased lignin content (G- and H-monomers), thereby solidifying the cell wall and inhibiting root growth [101].

Interestingly, in addition to ρ-coumaric acid and derivatives, the prevalence of ferulic acid and derivatives has been also identified in grafted plants. However, unlike the former, the latter enhances basipetal auxin transport. Furthermore, it functions dynamically by stimulating the IAA oxidase activity at its low level and hindering the enzyme activity at a high level [100]. An increase in diferulic acid, an oxidized product of ferulic acid, has been associated with the cell wall rigidity potentially by enhancing the matrix polysaccharides cross-link [102][103].

7. Conclusion

Like in other fields of plant science, plant grafting is moving ahead dynamically, especially in herbaceous vegetables. However, tree species pose special hindrances due to their much longer life span. The observations and findings from the herbaceous models can be relatable, and thus can be taken as a reference for woody plants. However, as discussed above, not all incompatible combinations exhibit the same features even within a similar plant model. Moreover, despite having a rich history of thousands of years of practice, graft-incompatibility has still remained enigmatic- particularly that between species with close phylogenetic relationships, those exhibiting differential reciprocal graft-compatibility efficiencies, and those exhibiting delayed incompatibility. Studies suggest that polyphenol and phenolic compounds play a vital role during the process and could be used as the metabolic markers of graft compatibility/incompatibility. Future studies are to confirm such postulation.

References

- Adhikari, P.B.; Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Zhu, S.; Kasahara, R.D. Fertilization in flowering plants: An odyssey of sperm cell delivery. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020, 103, 9–32.

- Hartmann, H.T.; Kester, D.E.; Davies, F.T., Jr. Plant Propagation. Principles and Practices, 8th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, UK, 2014.

- Mudge, K.; Janick, J.; Scofield, S.; Goldschmidt, E.E. A history of grafting. In Horticultural Reviews; 2009; pp. 437–493.

- Maiti, R.; Rodríguez, H.G.; Ac, P.; Kumari, C.A.; Sarkar, N.C. A comparative wood anatomy of 15 woody species in north-eastern mexico. For. Res. 2016, 5, 166.

- Herrero, J. Studies of compatible and incompatible graft combinations with special reference to hardy fruit trees. J. Hortic. Sci. 1951, 26, 186–237.

- Zarrouk, O.; Gogorcena, Y.; Moreno, M.Á.; Pinochet, J. Graft compatibility between peach cultivars and Prunus rootstocks. Hortscience 2006, 41, 1389–1394.

- Moing, A.; Carde, J.-P. Growth, cambial activity and phloem structure in compatible and incompatible peach/plum grafts. Tree Physiol. 1988, 4, 347–359.

- Moing, A.; Salesses, G.; Saglio, P.H. Growth and the composition and transport of carbohydrate in compatible and incom-patible peach/plum grafts. Tree Physiol. 1987, 3, 345–354.

- Zarrouk, O.; Testillano, P.S.; Risueño, M.D.C.; Moreno, M.Á.; Gogorcena, Y. Changes in cell/tissue organization and peroxi-dase activity as markers for early detection of graft incompatibility in peach/plum combinations. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2010, 135, 9–17.

- Rasool, A.; Mansoor, S.; Bhat, K.M.; Hassan, G.I.; Baba, T.R.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Alsahli, A.A.; El-Serehy, H.A.; Paray, B.A.; Ah-mad, P. Mechanisms underlying graft union formation and rootstock scion interaction in horticultural plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 590847.

- Errea, P. Implications of phenolic compounds in graft incompatibility in fruit tree species. Sci. Hortic. 1998, 74, 195–205.

- Loupit, G.; Cookson, S.J. Identifying molecular markers of successful graft union formation and compatibility. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11.

- Čolić, S.; Fotirić-Akšić, M.; Rakonjac, V.; Nikolić, D. Predicting delayed graft incompatibility in sweet cherry by peroxidase isoenzyme analysis. Voćarstvo 2015, 49, 107–113.

- Habibi, F.; Liu, T.; Folta, K.M.; Sarkhosh, A. Physiological, biochemical, and molecular aspects of grafting in fruit trees. Hor-tic. Res. 2022, 9.

- Liu, Y. Darwin's pangenesis and graft hybridization. In Advances in Genetics, Kumar, D., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 102, pp. 27–66.

- Tubbs, F.R. Growth relations of rootstock and scion in apples. J. Hortic. Sci. 1980, 55, 181–189.

- Castle, W.S. A career perspective on citrus rootstocks, their development, and commercialization. HortScience 2010, 45, 11–15.

- Iacono, F.; Peterlunger, E. Rootstock-scion interaction may affect drought tolerance in vitis vinifera cultivars. Implications in selection programs. Acta Hortic. 2000, 543–549.

- Okudai, N.; Yoshinaga, K.; Takahara, T.; Ishiuchi, D.; Oiyama, I. Studies on the promotion of flowering and fruiting of juve-nile citrus seedlings. II: Effect of grafting. Bull. Fruit Tree Res. Stn. D 1980, 2, 15–28.

- de Oliveira Castro, C.A.; dos Santos, G.A.; Takahashi, E.K.; Pires Nunes, A.C.; Souza, G.A.; de Resende, M.D.V. Accelerating Eucalyptus breeding strategies through top grafting applied to young seedlings. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 171, 113906.

- Cerruti, E.; Gisbert, C.; Drost, H.-G.; Valentino, D.; Portis, E.; Barchi, L.; Prohens, J.; Lanteri, S.; Comino, C.; Catoni, M. Grafting vigour is associated with DNA de-methylation in eggplant. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 241.

- Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Yu, H.; Jia, H.; Tan, C.; Hu, G.; Hu, Y.; Rao, M.J.; Deng, X.; et al. Genome of a citrus rootstock and global DNA demethylation caused by heterografting. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 69.

- Amos, J.; Hatton, R.G.; Hoblyn, T.N.; Knight, R.C. The effect of scion on root.: II. Stem-worked apples. J. Pomol. Hortic. Sci. 1930, 8, 248–258.

- Tandonnet, J.P.; Cookson, S.J.; Vivin, P.; Ollat, N. Scion genotype controls biomass allocation and root development in grafted grapevine. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2010, 16, 290–300.

- Gautier, A.T.; Merlin, I.; Doumas, P.; Cochetel, N.; Mollier, A.; Vivin, P.; Lauvergeat, V.; Péret, B.; Cookson, S.J. Identifying roles of the scion and the rootstock in regulating plant development and functioning under different phosphorus supplies in grapevine. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 185, 104405.

- Gautier, A.T.; Cochetel, N.; Merlin, I.; Hevin, C.; Lauvergeat, V.; Vivin, P.; Mollier, A.; Ollat, N.; Cookson, S.J. Scion genotypes exert long distance control over rootstock transcriptome responses to low phosphate in grafted grapevine. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 367.

- Tandonnet, J.-P.; Marguerit, E.; Cookson, S.J.; Ollat, N. Genetic architecture of aerial and root traits in field-grown grafted grapevines is largely independent. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 903–915.

- Gautier, A.T.; Chambaud, C.; Brocard, L.; Ollat, N.; Gambetta, G.A.; Delrot, S.; Cookson, S.J. Merging genotypes: Graft union formation and scion–rootstock interactions. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 70, 747–755.

- Wooldridge, T.J.S. Cross-Compatibility, Graft-Compatibility, and Phylogenetic Relationships in the Aurantioideae: New Data from the Balsamocitrinae; University of California: Riverside, CA, USA, 2016.

- Andrews, P.K.; Marquez, C.S. Graft incompatibility. Hortic. Rev. 1993, 15, 183–232.

- Copes, D. Graft union formation in douglas-fir. Am. J. Bot. 1969, 56, 285–289.

- Pina, A.; Errea, P. A review of new advances in mechanism of graft compatibility–incompatibility. Sci. Hortic. 2005, 106, 1–11.

- Asante, A.K.; Barnett, J.R. Graft union formation in mango (Mangifera indica L.). J. Hortic. Sci. 1997, 72, 781–790.

- Ermel, F.F.; Poëssel, J.L.; Faurobert, M.; Catesson, A.M. Early scion/stock junction in compatible and incompatible pear/pear and pear/quince grafts: A histo-cytological study. Ann. Bot. 1997, 79, 505–515.

- Yeoman, M.M. Cellular recognition systems in grafting. In Cellular Interactions, Linskens, H.F., Heslop-Harrison, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; pp. 453–472.

- Wulf, K.E.; Reid, J.B.; Foo, E. What drives interspecies graft union success? Exploring the role of phylogenetic relatedness and stem anatomy. Physiol. Plant. 2020, 170, 132–147.

- Notaguchi, M.; Kurotani, K.-i.; Sato, Y.; Tabata, R.; Kawakatsu, Y.; Okayasu, K.; Sawai, Y.; Okada, R.; Asahina, M.; Ichihashi, Y.; et al. Cell-cell adhesion in plant grafting is facilitated by β-1,4-glucanases. Science 2020, 369, 698–702.

- Santamour, F.S. Graft incompatibility related to cambial peroxidase isozymes in chinese chestnut. J. Environ. Hortic. 1988, 6, 33–39.

- Gulen, H.; Arora, R.; Kuden, A.; Krebs, S.L.; Postman, J. Peroxidase isozyme profiles in compatible and incompatible pear-quince graft combinations. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2002, 127, 152–157.

- Irisarri, P.; Binczycki, P.; Errea, P.; Martens, H.J.; Pina, A. Oxidative stress associated with rootstock–scion interactions in pear/quince combinations during early stages of graft development. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 176, 25–35.

- Marín, D.; Armengol, J.; Carbonell-Bejerano, P.; Escalona, J.M.; Gramaje, D.; Hernández-Montes, E.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Mar-tínez-Zapater, J.M.; Medrano, H.; Mirás-Avalos, J.M.; et al. Challenges of viticulture adaptation to global change: Tackling the issue from the roots. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2021, 27, 8–25.

- Waite, H.; Armengol, J.; Billones-Baaijens, R.; Gramaje, D.; Hallen, F.; Marco, S.D.; Smart, R. A protocol for the management of grapevine rootstock mother vines to reduce latent infections by grapevine trunk pathogens in cuttings. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2018, 57, 384–398.

- Swarbrick, T. The healing of wounds in woody stems. J. Pomol. Hortic. Sci. 1925, 5, 98–114.

- Levy, A.; Epel, B.L. Chapter 4.4.2—cytology of the (1-3)-β-glucan (callose) in plasmodesmata and sieve plate pores. In Chem-istry, Biochemistry, and Biology of 1-3 Beta Glucans and Related Polysaccharides, Bacic, A., Fincher, G.B., Stone, B.A., Eds.; Ac-ademic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 439–463.

- Denaxa, N.-K.; Vemmos, S.N.; Roussos, P.A. Shoot girdling improves rooting performance of kalamata olive cuttings by up-regulating carbohydrates, polyamines and phenolic compounds. Agriculture 2021, 11, 71.

- Basak, U.C.; Das, A.B.; Das, P. Rooting response in stem cuttings from five species of mangrove trees: Effect of auxins and en-zyme activities. Mar. Biol. 2000, 136, 185–189.

- Howard, B.H. Manipulating rooting potential in stockplants before collecting cuttings. In Biology of Adventitious Root For-mation, Davis, T.D., Haissig, B.E., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 123–142.

- Aloni, B.; Karni, L.; Deventurero, G.; Levin, Z.; Cohen, R.; Katzir, N.; Lotan-Pompan, M.; Edelstein, M.; Aktas, H.; Turhan, E.; et al. Physiological and biochemical changes at the rootstock-scion interface in graft combinations between Cucurbita root-stocks and a melon scion. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2008, 83, 777–783.

- Barbier, F.F.; Dun, E.A.; Beveridge, C.A. Apical dominance. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R864–R865.

- Sanbagavalli, S.; Bhavana, J.; Pavithra, S. Nipping—A simple strategy to boost the yield—Review. Ann. Res. Rev. Biol. 2020, 35, 45–51.

- Jeffree, C.E.; Yeoman, M.M. Development of intercellular connections between opposing cells in a graft union. New Phytol. 1983, 93, 491–509.

- Moore, R.; Walker, D.B. Studies of vegetative compatibility-incompatibility in higher plants. I. A structural study of a com-patible autograft in Sedum telephoides (crassulaceae). Am. J. Bot. 1981, 68, 820–830.

- Trinchera, A.; Pandozy, G.; Rinaldi, S.; Crinò, P.; Temperini, O.; Rea, E. Graft union formation in artichoke grafting onto wild and cultivated cardoon: An anatomical study. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 1569–1578.

- Asante, A. Compatibility studies on cashew-mango graft combinations. Ghana J. Agric. Sci. 2001, 34, 3–9.

- Moore, R.; Walker, D.B. Studies of vegetative compatibility-incompatibility in higher plants. II. A structural study of an in-compatible heterograft between Sedum telephoides (crassulaceae) and Solanum pennellii (solanaceae). Am. J. Bot. 1981, 68, 831–842.

- Cookson, S.J.; Clemente Moreno, M.J.; Hevin, C.; Nyamba Mendome, L.Z.; Delrot, S.; Trossat-Magnin, C.; Ollat, N. Graft union formation in grapevine induces transcriptional changes related to cell wall modification, wounding, hormone signalling, and secondary metabolism. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 2997–3008.

- Zhang, A.; Matsuoka, K.; Kareem, A.; Robert, M.; Roszak, P.; Blob, B.; Bisht, A.; De Veylder, L.; Voiniciuc, C.; Asahina, M.; et al. Cell-wall damage activates DOF transcription factors to promote wound healing and tissue regeneration in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 1883–1894.

- Savatin, D.V.; Gramegna, G.; Modesti, V.; Cervone, F. Wounding in the plant tissue: The defense of a dangerous passage. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 470.

- Daher, F.B.; Braybrook, S.A. How to let go: Pectin and plant cell adhesion. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 523.

- Atakhani, A.; Bogdziewiez, L.; Verger, S. Characterising the mechanics of cell–cell adhesion in plants. Quant. Plant Biol. 2022, 3, E2.

- Kollmann, R.; Glockmann, C. Studies on graft unions. I. Plasmodesmata between cells of plants belonging to different unre-lated taxa. Protoplasma 1985, 124, 224–235.

- Pina, A.; Errea, P. Cellular viability and pectin localisation in apricot (P. armeniaca)/plum combinations related to graft re-sponse. In XIII International Symposium on Apricot Breeding and Culture 717; 2006; pp. 185–188.

- Pina, A.; Errea, P.; Martens, H.J. Graft union formation and cell-to-cell communication via plasmodesmata in compatible and incompatible stem unions of Prunus spp. Sci. Hortic. 2012, 143, 144–150.

- Wang, J.; Li, D.; Chen, N.; Chen, J.; Mu, C.; Yin, K.; He, Y.; Liu, H. Plant grafting relieves asymmetry of jasmonic acid response induced by wounding between scion and rootstock in tomato hypocotyl. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241317.

- Bao, W.-W.; Zhang, X.-C.; Zhang, A.L.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Q.-C.; Liu, Z.-D. Validation of micrografting to analyze compatibility, shoot growth, and root formation in micrografts of kiwifruit (Actinidia spp.). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2020, 140, 209–214.

- Errea, P.; Felipe, A.; Herrero, M. Graft establishment between compatible and incompatible Prunus spp. J. Exp. Bot. 1994, 45, 393–401.

- Melnyk, C.W.; Schuster, C.; Leyser, O.; Meyerowitz, E.M. A developmental framework for graft formation and vascular re-connection in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, 1306–1318.

- Wagner, D. Ultrastructure of the bud graft union in Malus. Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 1968.

- Melnyk, C.W.; Gabel, A.; Hardcastle, T.J.; Robinson, S.; Miyashima, S.; Grosse, I.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Transcriptome dynamics at Arabidopsis graft junctions reveal an intertissue recognition mechanism that activates vascular regeneration. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E2447–E2456.

- Hall, P.; Badenoch-Jones, J.; Parker, C.; Letham, D.; Barlow, B. Identification and quantification of cytokinins in the xylem sap of mistletoes and their hosts in relation to leaf mimicry. Funct. Plant Biol. 1987, 14, 429–438.

- Bogoeva, V.; Ivanov, I.; Kulina, H.; Russev, G.; Atanasova, L. A novel cytokinin-binding property of mistletoe lectin I from Viscum album. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2013, 27, 3583–3585.

- Zhang, X.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A.; Duan, J.; Deng, R.; Xu, X.; Ma, G. Endogenous hormone levels and anatomical characters of haustoria in Santalum album L. seedlings before and after attachment to the host. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 859–866.

- Moore, R. A model for graft compatibility-incompatibility in higher plants. Am. J. Bot. 1984, 71, 752–758.

- Santamour, F.S. Graft compatibility in woody plants: An expanded perspective. J. Environ. Hortic. 1988, 6, 27–32.

- Morris, H.; Hietala, A.M.; Jansen, S.; Ribera, J.; Rosner, S.; Salmeia, K.A.; Schwarze, F.W.M.R. Using the CODIT model to ex-plain secondary metabolites of xylem in defence systems of temperate trees against decay fungi. Ann. Bot. 2019, 125, 701–720.

- Nanda, A.K.; Melnyk, C.W. The role of plant hormones during grafting. J. Plant Res. 2018, 131, 49–58.

- Qureshi, M.A.; Jaskani, M.J.; Khan, A.S.; Ahmad, R. Influence of endogenous plant hormones on physiological and growth attributes of kinnow mandarin grafted on nine rootstocks. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41, 1254–1264.

- Tworkoski, T.; Fazio, G. Physiological and morphological effects of size-controlling rootstocks on 'Fuji' apple scions. Acta Hortic. 2011, 903, 865–872.

- Kamboj, J.S.; Browning, G.; Blake, P.S.; Quinlan, J.D.; Baker, D.A. GC-MS-SIM analysis of abscisic acid and indole-3-acetic acid in shoot bark of apple rootstocks. Plant Growth Regul. 1999, 28, 21–27.

- Kumari, A.; Kumar, J.; Kumar, A.; Chaudhury, A.; Singh, S.P. Grafting triggers differential responses between scion and root-stock. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124438–e0124438.

- He, W.; Xie, R.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, H.; Yang, S.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, H.; Gmitter, F.G., Jr.; et al. Comparative tran-scriptomic analysis on compatible/incompatible grafts in Citrus. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9.

- Dhakar, M.K.; Das, B. Standardization of grafting technique in litchi. Indian J. Hortic 2017, 74, 16–19.

- Smith, D.D.; Sperry, J.S. Coordination between water transport capacity, biomass growth, metabolic scaling and species stature in co-occurring shrub and tree species. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 2679–2690.

- Eleftheriou, E.P. A decline-like disorder of pear in Greece: Pear decline or scion—Rootstock incompatibility? Sci. Hortic. 1985, 27, 241–250.

- Gebhardt, K.; Feucht, W. Polyphenol changes at the union of Prunus avium/Prunus cerasus grafts. J. Hortic. Sci. 1982, 57, 253–258.

- Guclu, S.F. Identification of polyphenols in homogenetic and heterogenetic combination of cherry grafting. Pak. J. Bot. 2019, 51, 2067–2072.

- Errea, P.; Garay, L.; Marín, J.A. Early detection of graft incompatibility in apricot (Prunus armeniaca) using in vitro tech-niques. Physiol. Plant. 2001, 112, 135–141.

- Ermel, F.F.; Kervella, J.; Catesson, A.M.; Poëssel, J.L. Localized graft incompatibility in pear/quince (Pyrus communis/Cydonia oblonga) combinations: Multivariate analysis of histological data from 5-month-old grafts. Tree Physiol. 1999, 19, 645–654.

- Schmid, P.P.S.; Feucht, W. Compatibility in Prunus avium/Prunus cerasus graftings during the initial phase. III. Isoelectro-focusing of proteins, peroxidases and acid phosphatases during union formation. J. Hortic. Sci. 1985, 60, 311–318.

- Deloire, A.; xc; Bant, C. Peroxidase activity and lignification at the interface between stock and scion of compatible and in-compatible grafts of Capsicum on Lycopersicum. Ann. Bot. 1982, 49, 887–891.

- Bruce, R.J.; West, C.A. Elicitation of lignin biosynthesis and isoperoxidase activity by pectic fragments in suspension cultures of castor bean. Plant Physiol. 1989, 91, 889–897.

- Baron, D.; Esteves Amaro, A.C.; Pina, A.; Ferreira, G. An overview of grafting re-establishment in woody fruit species. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 243, 84–91.

- Dunand, C.; De Meyer, M.; Crèvecoeur, M.; Penel, C. Expression of a peroxidase gene in zucchini in relation with hypocotyl growth. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2003, 41, 805–811.

- Sasaki, S.; Baba, K.i.; Nishida, T.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Kondo, R. The cationic cell-wall-peroxidase having oxidation ability for polymeric substrate participates in the late stage of lignification of Populus alba L. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006, 62, 797–807.

- Reimers, P.J.; Guo, A.; Leach, J.E. Increased activity of a cationic peroxidase associated with an incompatible interaction be-tween Xanthomonas oryzae pv oryzae and rice (Oryza sativa). Plant Physiol. 1992, 99, 1044–1050.

- Milinović, B.; Dragović-Uzelac, V.; Kazija, D.H.; Jelačić, T.; Vujević, P.; Čiček, D.; Biško, A.; Čmelik, Z. Influence of four differ-ent dwarfing rootstocks on phenolic acids and anthocyanin composition of sweet cherry ( Prunus avium L) cvs ‘Kordia’ and ‘Regina’. J. Appl. Bot Food Qual. 2016, 89, 29–37.

- Mng’omba, S.A.; du Toit, E.S.; Akinnifesi, F.K. The relationship between graft incompatibility and phenols in Uapaca kirk-iana Müell Arg. Sci. Hortic. 2008, 117, 212–218.

- Gamba, G.; Cisse, V.; Donno, D.; Razafindrakoto, Z.R.; Beccaro, G.L. Quali-quantitative study on phenol compounds as early predictive markers of graft incompatibility: A case study on chestnut (Castanea spp.). Horticulturae 2022, 8, 32.

- Treutter, D.; Feucht, W. Accumulation of the flavonoid prunin in Prunus avium/P. cerasus grafts and its possible involvement in the process of incompatibility. Acta Hortic. 1988, 227, 74–78.

- Lochard, R.G.; Schneider, G.W. Stock and scion growth relationships and the dwarfing mechanism in apple. In Horticultural Reviews, Janick, J., Ed.; AVI Publishing Company, Inc.: Westport, CT, USA, 1981; Volume 3, pp. 315–375.

- Zanardo, D.I.L.; Lima, R.B.; Ferrarese, M.d.L.L.; Bubna, G.A.; Ferrarese-Filho, O. Soybean root growth inhibition and lignifi-cation induced by p-coumaric acid. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 66, 25–30.

- Kamisaka, S.; Takeda, S.; Takahashi, K.; Shibata, K. Diferulic and ferulic acid in the cell wall of Avena coleoptiles—Their relationships to mechanical properties of the cell wall. Physiol. Plant. 1990, 78, 1–7.

- Tan, K.-S.; Hoson, T.; Masuda, Y.; Kamisaka, S. Correlation between cell wall extensibility and the content of diferulic and ferulic acids in cell walls of Oryza sativa coleoptiles grown under water and in air. Physiol. Plant. 1991, 83, 397–403.