| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LEONIE ASFORA SARUBBO | -- | 3357 | 2023-02-14 13:05:52 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 3357 | 2023-02-15 04:13:21 | | |

Video Upload Options

Fuel and oil spills during the exploration, refining, and distribution of oil and petrochemicals are primarily responsible for the accumulation of organic pollutants in the environment. The reduction in contamination caused by hydrocarbons, heavy metals, oily effluents, and particulate matter generated by industrial activities and the efficient recovery of oil at great depths in an environmentally friendly way pose a challenge, as recovery and cleaning processes require the direct application of surface-active agents, detergents, degreasers, or solvents, often generating other environmental problems due to the toxicity and accumulation of these substances. Thus, the application of natural surface-active agents is an attractive solution. Due to their amphipathic structures, microbial surfactants solubilize oil through the formation of small aggregates (micelles) that disperse in water, with numerous applications in the petroleum industry. Biosurfactants have proven their usefulness in solubilizing oil trapped in rock, which is a prerequisite for enhanced oil recovery (EOR). Biosurfactants are also important biotechnological agents in anti-corrosion processes, preventing incrustations and the formation of biofilms on metallic surfaces, and are used in formulations of emulsifiers/demulsifiers, facilitate the transport of heavy oil through pipelines, and have other innovative applications in the oil industry. The use of natural surfactants can reduce the generation of pollutants from the use of synthetic detergents or chemical solvents without sacrificing economic gains for the oil industry.

1. Application of Biosurfactants in Soil Remediation

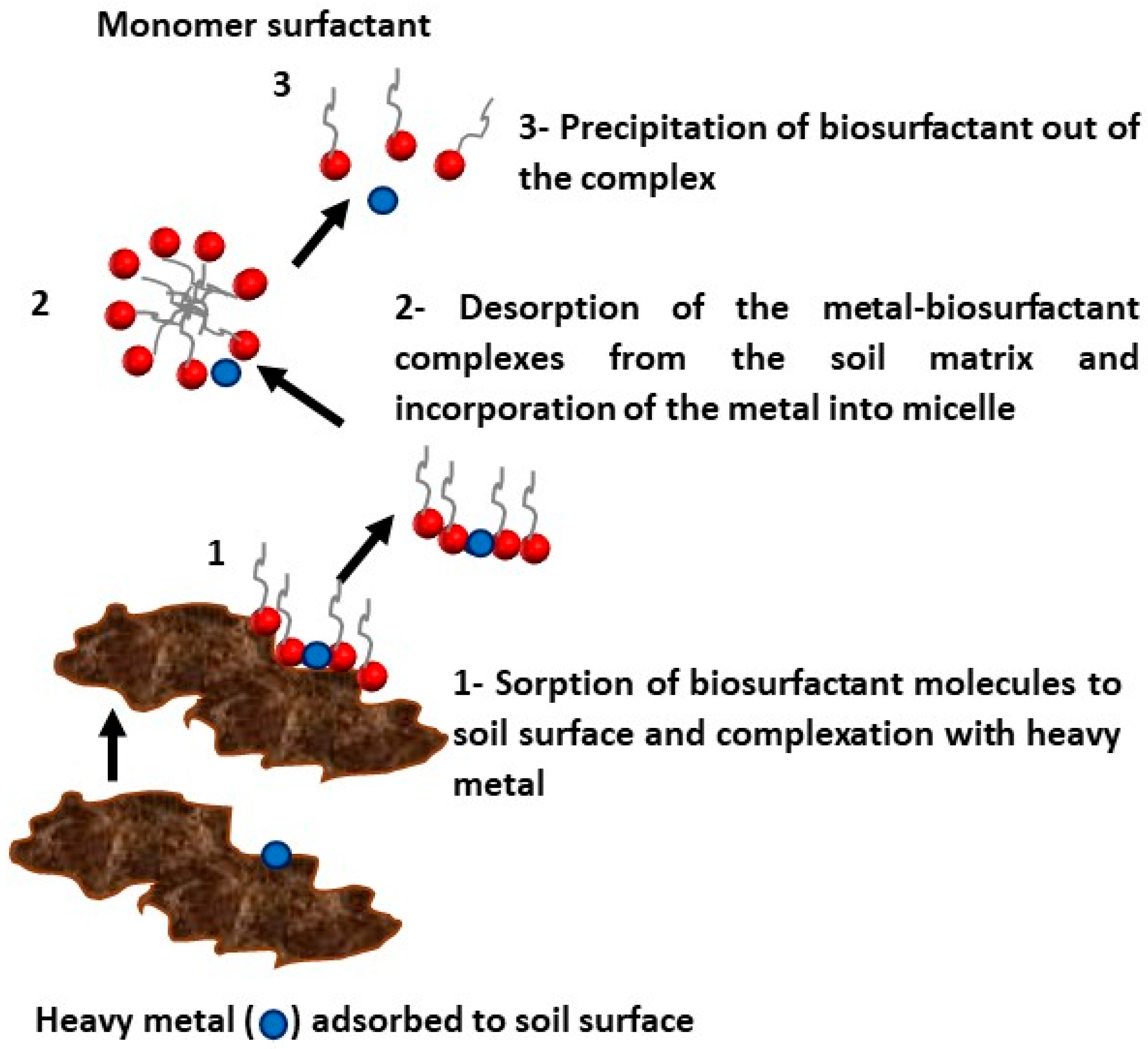

2. Application of Biosurfactants for Removal of Heavy Metals

3. Application of Biosurfactants for Bioremediation of Marine Environment

4. Application of Biosurfactants for Oil Recovery from Reservoirs

5. Application of Biosurfactants in Transport of Crude Oil through Pipelines

References

- Faccioli, Y.E.S.; Silva, G.O.; Soares da Silva, R.C.F.; Sarubbo, L.A. Application of a biosurfactant from Pseudomonas cepacia CCT 6659 in bioremediation and metallic corrosion inhibition processes. J. Biotechnol. 2022, 351, 109–121.

- Fenibo, E.O.; Ijoma, G.N.; Selvarajan, R.; Chikere, C.B. Microbial surfactants: The next generation multifunctional biomolecules for applications in the petroleum industry and its associated environmental remediation. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 581.

- Sales da Silva, I.G.; Almeida, F.C.G.; Rocha e Silva, N.M.P.; Casazza, A.A.; Converti, A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Soil bioremediation: Overview of technologies and trends. Energies 2020, 13, 4664.

- Ławniczak, Ł.; Wo´zniak-Karczewska, M.; Loibner, A.P.; Heipieper, H.J.; Chrzanowski, Ł. Microbial degradation of hydrocarbons—Basic principles for bioremediation: A review. Molecules 2020, 25, 856.

- Chaprão, M.J.; Ferreira, I.N.S.; Correa, P.F.; Rufino, R.D.; Luna, J.M.; Silva, E.J.; Sarubbo, L.A. Application of bacterial and yeast biosurfactants for enhanced removal and biodegradation of motor oil from contaminated sand. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 18, 471–479.

- Bustamante, M.; Duran, N.; Diez, M.C. Biosurfactants are useful tools for the bioremediation of contaminated soil: A review. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2012, 12, 667–687.

- Silva, E.J.; Luna, J.M.; Rufino, R.D.; Silva, R.O.; Sarubbo, L.A. Characterization of a biosurfactant produced by Pseudomonas cepacia CCT6659 in the presence of industrial wastes and its application in the biodegradation of hydrophobic compounds in soil. Colloids Surf. B 2014, 117, 36–41.

- Itrich, N.R.; McDonough, K.M.; Van Ginkel, C.G.; Bisinger, E.C.; LePage, J.N.; Schaefer, E.C.; Menzies, J.Z.; Casteel, K.D.; Federle, T.W. Widespread microbial adaptation to L-glutamate-N, N-diacetate (L-GLDA) ollowing its market introduction in a consumer cleaning product. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 13314–13321.

- Sachdev, D.P.; Cameotra, S.S. Biosurfactants in agriculture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 1005–1016.

- Rawat, G.; Dhasmana, A.; Kumar, V. Biosurfactants: The next generation biomolecules for diverse applications. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 3, 353–369.

- Ariffin, N.; Abdullah, M.M.; Zainol, M.R.; Murshed, M.F.; Faris, M.A.; Bayuaji, R. Review on adsorption of heavy metal in wastewater by using geopolymer. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 97, 01023.

- Rocha Junior, R.B.; Meira, H.M.; Almeida, D.G.; Rufino, R.D.; Luna, J.M.; Santos, V.A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Application of a low-cost biosurfactant in heavy metal remediation processes. Biodegradation 2019, 30, 215–233.

- Sarubbo, L.A.; Rocha Junior, R.B.; Luna, J.M.; Rufino, R.D.; Santos, V.A.; Banat, I.M. Some aspects of heavy metals contamination remediation and role of biosurfactants. Chem. Ecol. 2015, 31, 707–723.

- Santos, D.K.F.; Luna, J.M.; Rufino, R.D.; Santos, V.A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Biosurfactants: Multifunctional biomolecules of the 21st century. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 401.

- Pacwa-Płociniczak, M.; Płaza, G.A.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z.; Cameotra, S.S. Environmental applications of biosurfactants: Recent advances. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 633–654.

- Liduino, V.S.; Servulo, E.F.; Oliveira, F.J. Biosurfactant-assisted phytoremediation of multi-contaminated industrial soil using sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2018, 53, 609–616.

- Luna, J.M.; Rufino, R.D.; Sarubbo, L.A. Biosurfactant from Candida sphaerica UCP0995 exhibiting heavy metal remediation properties. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2016, 102, 558–566.

- Sarubbo, L.A.; Brasileiro, P.P.F.; Silveira, G.N.M.; Luna, J.M.; Rufino, R.D.; Santos, V.A. Application of a low cost biosurfactant in the removal of heavy metals in soil. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2018, 64, 433–438.

- Qi, X.; Xu, X.; Zhong, C.; Jiang, T.; Wei, W.; Song, X. Removal of cadmium and lead from contaminated soils using sophorolipids from fermentation culture of Starmerella bombicola CGMCC 1576 fermentation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2334.

- Almeida, D.G.; Soares da Silva, R.C.F.; Luna, J.M.; Rufino, R.D.; Santos, V.A.; Banat, I.M.; Sarubbo, L.A. Biosurfactants: Promising molecules for petroleum biotechnology advances. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1718.

- El Gheriany, I.A.; El Saqa, F.A.; Amer, A.A.E.R.; Hussein, M. Oil spill sorption capacity of raw and thermally modified orange peel waste. Alexandria Eng. J. 2020, 59, 925–932.

- Faksness, L.G.; Brandvik, P.J.; Daling, P.S.; Singsaas, I.; Sorstrom, S.E. The value of offshore field experiments in oil spill techology development for Norwegian waters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 111, 402–410.

- Edwards, K.R.; Leop, J.E.; Lewis, M.A. Toxicity comparison of biosurfactants and synthetic surfactants used in oil spill remediation to two estuarine species. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2003, 46, 1309–1316.

- Shakeri, F.; Babavalian, H.; Amoozegar, M.A.; Ahmadzadeh, Z.; Zuhuriyanizadi, S.; Afsharian, M.P. Production and application of biosurfactants in biotechnology. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 11, 10446–10460.

- Silva, I.A.; Almeida, F.C.G.; Souza, T.C.; Bezerra, K.G.O.; Durval, I.J.B.; Converti, A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Oil spills: Impacts and perspectives of treatment technologies with focus on the use of green surfactants. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 143.

- Patel, S.; Homaei, A.; Patil, S.; Daverey, A. Microbial biosurfactants for oil spill remediation: Pitfalls and potentials. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 27–37.

- Cui, C.Z.; Zeng, C.; Wan, X.; Chen, D.; Zhang, J.Y.; Shen, P. Effect of rhamnolipids on degradation of anthracene by two newly isolated strains, Sphingomonas sp. 12A and Pseudomonas sp. 12B. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 18, 63–66.

- Liu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Zhong, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, M.; Liu, G.; Liu, S. Effect of rhamnolipid solubilization on hexadecane bioavailability: Enhancement or reduction? J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 322, 394–401.

- Silva, E.J.; Correa, P.F.; Almeida, D.G.; Luna, J.M.; Rufino, R.D.; Sarubbo, L.A. Recovery of contaminated marine environments by biosurfactant-enhanced bioremediation. Colloids Surf. B 2018, 172, 127–135.

- Freitas, B.G.; Brito, J.G.M.; Brasileiro, P.P.F.; Rufino, R.D.; Luna, J.M.; Santos, V.A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Formulation of a commercial biosurfactant for application as a dispersant of petroleum and by-products spilled in oceans. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1646.

- Santos, D.K.F.; Resende, A.H.M.; Almeida, D.G.; Soares da Silva, R.C.F.; Rufino, R.D.; Luna, J.M.; Sarubbo, L.A. Evaluation of remediation processes with a biosurfactant from Candida lipolytica UCP0988 and the formulation of a commercial bioremediation agent. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 767.

- Durval, I.J.B.; Mendonça, A.H.R.; Luna, J.M.; Rufino, R.D.; Sarubbo, L.A. Studies on biosurfactant from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens isolated from sea water with biotechnological potential for marine oil spill bioremediation. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2019, 22, 349–363.

- Durval, I.J.B.; Resende, A.H.M.; Rocha, I.V.; Luna, J.M.; Rufino, R.D.; Converti, A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Production, characterization, evaluation and toxicity assessment of a Bacillus cereus UCP 1615 biosurfactant for marine oil spills bioremediation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 157, 111357.

- Ostendorf, T.A.; Silva, I.A.; Converti, A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Production and formulation of a new low-cost biosurfactant to remediate oil-contaminated seawater. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 295, 71–79.

- Soares da Silva, R.C.F.; Luna, J.M.; Rufino, R.D.; Sarubbo, L.A. Ecotoxicity of the formulated biosurfactant from Pseudomonas cepacia CCT 6659 and application in the bioremediation of terrestrial and aquatic environments impacted by oil spills. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 154, 338–347.

- Jin, L.; Garamus, V.M.; Liu, F.; Xiao, J.; Eckerlebe, H.; Willumeit-Römer, R.; Mu, B.; Zou, A. Interaction of a biosurfactant, surfactin with a cationic gemini surfactant in aqueous solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 481, 201–209.

- Shah, M.U.H.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Sivapragazam, M.; Talukder, M.R.; Yusup, S.B.; Goto, M. A binary mixture of a biosurfactant and an ionic liquid surfactant as a green dispersant for oil spill remediation. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 280, 111–119.

- Camara, J.M.; Sousa, M.A.; Neto, E.B.; Oliveira, M.C. Application of rhamnolipid biosurfactant produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in microbial-enhanced oil recovery (MEOR). J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2019, 1, 2333–2341.

- Geetha, S.J.; Banat, I.M.; Joshi, S.J. Biosurfactants: Production and potential applications in microbial enhanced oil recovery (MEOR). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 14, 23–32.

- Al-Bahry, S.N.; Al-Wahaibi, Y.M.; Elshafie, A.E.; Al-Bemani, A.S.; Joshi, S.J.; Al-Makhmari, H.S.; Al-Sulaimani, H.S. Biosurfactant production by Bacillus subtilis B20 using date molasses and its possible application in enhanced oil recovery. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 81, 141–146.

- Golabi, E.; Sogh, S.R.; Hosseini, S.N.; Gholamzadeh, M.A. Biosurfactant production by microorganism for enhanced oil recovery. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2012, 3, 1–6.

- Rufino, R.D.; Luna, J.M.; Marinho, P.H.C.; Farias, C.B.B.; Ferreira, S.R.M.; Sarubbo, L.A. Removal of petroleum derivative adsorbed to soil by biosurfactant Rufisan produced by Candida lipolytica. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2013, 109, 117–122.

- Sales da Silva, I.G.S.; Rocha e Silva, N.M.P.; Oliveira, J.T.R.; Almeida, F.C.G.; Converti, A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Application of green surfactants in the remediation of soils contaminated by petroderivates. Processes 2021, 9, 1666.

- Datta, P.; Tiwari, P.; Pandey, L.M. Oil washing proficiency of biosurfactant produced by isolated Bacillus tequilensis MK 729017 from Assam reservoir soil. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 195, 107612.

- Silva, R.C.F.S.; Almeida, D.G.; Rufino, R.D.; Luna, J.M.; Santos, V.A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Applications of biosurfactants in the petroleum industry and the remediation of oil spills. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 12523–12542.

- Chaprão, M.J.; Soares da Silva, R.C.F.; Rufino, R.D.; Luna, J.M.; Santos, V.A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Production of a biosurfactant from Bacillus methylotrophicus UCP1616 for use in the bioremediation of oil-contaminated environments. Ecotoxicology 2018, 27, 1310–1322.

- Adrion, A.C.; Nakamura, J.; Shea, D.; Aitken, M.D. Screening nonionic surfactants for enhanced biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons remaining in soil after conventional biological treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 50, 3838–3845.

- Ceron-Camacho, R.; Martínez-Palou, R.; Chavez-Gomez, B.; Cuéllar, F.; Bernal-Huicochea, C.; Aburto, J. Synergistic effect of alkyl-O-glucoside and-cellobioside biosurfactants as effective emulsifiers of crude oil in water: A proposal for the transport of heavy crude oil by pipeline. Fuel 2013, 110, 310–317.

- El-Sheshtawy, H.S.; Khidr, T.T. Some bio-surfactants used as pour point depressant for waxy egyptian crude oil. Petroleum Sci. Technol. 2016, 34, 1475–1482.

- Mazaheri-Assadi, M.; Tabatabaee, M.S. Biosurfactants and their use in upgrading petroleum vacuum distillation residue: A review. Inter. J. Environ. Res. 2010, 4, 549–572.

- Wang, Z.; Yu, X.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L. The use of bio-based surfactant obtained by enzymatic syntheses for wax deposition inhibition and drag reduction in crude oil pipelines. Catalysts 2016, 6, 61.