Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amaresh K Ranjan | -- | 7025 | 2023-02-09 13:38:04 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 7025 | 2023-02-10 02:08:10 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ranjan, A.K.; Gulati, A. Regulation of Central and Peripheral Blood Pressure. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41049 (accessed on 11 March 2026).

Ranjan AK, Gulati A. Regulation of Central and Peripheral Blood Pressure. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41049. Accessed March 11, 2026.

Ranjan, Amaresh K., Anil Gulati. "Regulation of Central and Peripheral Blood Pressure" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41049 (accessed March 11, 2026).

Ranjan, A.K., & Gulati, A. (2023, February 09). Regulation of Central and Peripheral Blood Pressure. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41049

Ranjan, Amaresh K. and Anil Gulati. "Regulation of Central and Peripheral Blood Pressure." Encyclopedia. Web. 09 February, 2023.

Copy Citation

Pressure in the primary arteries near the heart and the brain is known as central blood pressure (CBP), while that in the peripheral arteries is known as peripheral blood pressure (PBP). Usually, CBP and PBP are correlated. However, various types of shocks and cardiovascular disorders interfere with their regulation, and consequently, their correlation is lost. Therefore, understanding blood pressure in normal and disease conditions is essential for managing shock-related cardiovascular implications and improving treatment outcomes.

blood pressure

cardiovascular disorder

hypertension

hypotension

hypoxia

1. Central and Peripheral Blood Pressure

The pressure exerted by the blood on the heart and the wall of blood vessels in the circulatory system is known as blood pressure, which is generated because of blood flow and vascular resistance during systolic and diastolic heart movements. Depending on the anatomical location of the blood vessel, the blood pressure is categorized into “central” (CBP) or “peripheral” (PBP) types. For example, CBP is the blood pressure in the aorta, where the blood gets pumped first from the heart’s left ventricle during its systolic movement. While on the other hand, blood pressure measured in the brachial artery (upper arm) or the radial artery (wrist) is known as PBP.

CBP is known to reflect the blood pressure in the heart, brain, and other vital organs; hence, it is considered a key determinant of cardiovascular health and diseases [1]. However, the measurement of PBP is a common practice by health professionals and is measured easily, quickly, and in a non-invasive manner [2]. The PBP measurement in the upper arm is one of the oldest methods to measure blood pressure, which is also used to diagnose high blood pressure or hypertension. Nonetheless, recent studies in hypertensive patients and animal models have delineated the importance of CBP measurement over PBP in predicting heart disease and stroke [1][3][4] and concluded that CBP is more accurate and useful than PBP. One of the main reasons for the difference between CBP and PBP is the inherent pulsatile nature of blood flow. After blood is ejected from the heart into the arterial system, blood flow, pressure, and a propagating pulse along the arterial bed are generated. The property of the pulse is like a periodically oscillating wave and is known as pulse wave (PW) or pulse pressure (PP). PW travels from the heart toward the peripheral arteries, and in clinical settings, it is quantified as the variation in systolic and diastolic blood pressure at a distinct site of the arterial tree (e.g., carotid artery, brachial artery, or radial artery). However, an increase in the whole amplitude of the PW, also known as “PW amplification” or “PP amplification”, is observed when it travels distally. The phenomenon of “PP amplification” leads to gradual widening of PW as it travels away from aorta in the arterial bed. The analysis of PW amplification indicates that typically, the diastolic and mean pressure changes are diminutive, but systolic pressure becomes significantly amplified as the wave moves from the aorta to the periphery [5]. The amplification (A) of the PW is determined as the ratio of the amplitude of PP at the proximal (PP1) to distal (PP2) location (A = PP2/PP1). Notably, with the amplification of PP, the wave amplification is without an additional energy requirement in the arterial system; hence, it is more like a distortion than true amplification. In hypertensive patients, this distortion is generally more intriguing and may lead to a condition where peripheral (brachial) systolic pressure does not reflect the status of the central (aortic) systolic pressure. For example, the study by Kelly et al. [6] on hypertensive patients showed that after nitroglycerin administration, aortic systolic pressure fell in all patients (~22 mmHg average decrease), whereas brachial systolic pressure remained unchanged or fell to a lesser degree (~12 mmHg average decrease). Thus, PP amplification may cause a condition of pseudo-hypertension in the peripheral vascular system, which may lead to the overuse of hypertensive drugs and severely affect the coronary and cerebral blood flow [7]. Hence, measuring CBP could be more helpful in managing hypertension and avoiding the side effects of hypertensive medications than PBP; however, more scientific research is needed to validate its use.

2. Regulation of Central and Peripheral Blood Pressure

Mechanistically, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) is determined by the cardiac output (CO) and peripheral vascular resistance (PVR), also known as systemic vascular resistance (SVR) [8][9][10]. CO indicates the amount of blood ejected from the left ventricle in one minute, while PVR is the resistance to the blood flow in the arteries and arterioles. The equation: MAP = CO × PVR, represents the interaction of two independent factors influenced by several cardiac activities and other physiological variables. CO is a derivative of heart rate (HR) and stroke volume (SV) and is represented with the equation: CO = HR × SV, where HR is beat per minute, and SV is the amount of blood ejected from the left ventricle with each contraction (beat). The SV depends on the left ventricle’s preload, contractility, and afterload. Hence, the overall equation of MAP could be represented as: MAP = HR × SV × PVR. Knowledge of physiological variables affecting HR, SV, and PVR is essential to understand blood pressure regulation because these variables act as effectors/targets for blood pressure control systems in our body.

Factors that affect the chronotropy (conductance of sinoatrial node), dromotropy (conductance of atrioventricular node), and lusitropy (relaxation) of the myocardium can modulate HR: the positive chronotropy and dromotropy increase the HR, while positive lusitropy decreases HR, and their effects are reversed when the factors negatively affect them [11][12]. An in vivo study on the dog heart by Raff et al. demonstrated that with end-diastolic pressure and mean aortic systolic pressure increase, the heart relaxed more slowly (negative lusitropy) [13]. Hence, the resultant MAP could be increased with positive chronotropy and dromotropy but decreased with positive lusitropy. SV is determined by ventricular preload, inotropy (contraction), and afterload. Blood volume and compliance of veins are known to affect preload. An increase in the blood volume increases the preload, which results in higher SV. Positive inotropy also increases SV, while an increase in afterload reduces the velocity of muscle fiber shortening and blood ejection velocity, which decreases the SV. Therefore, the resultant MAP could be increased with increased preload and positive inotropy, while it could be decreased with increased afterload.

SVR depends on the radius and length of the blood vessels along with the viscosity of the blood. However, the major change in SVR in the body is performed by the regulation of the vessel radius. A change in the radius leads to a dramatic change in resistance because resistance is inversely proportional to the fourth power of the vessel radius. Therefore, a slight decrease in the arteriole diameter can result in a large increase in SVR, and vice versa. Since vessel length is not subjected to change in the body, it has a negligible effect on SVR. Viscosity is known to play a minor role in SVR. However, an increase in the hematocrit level may increase the blood viscosity, which results in enhanced SVR [14]. Hence, a decrease in the vessel radius increases SVR and leads to an increase in blood pressure, and the effect will be the opposite with an increase in the vessel diameter.

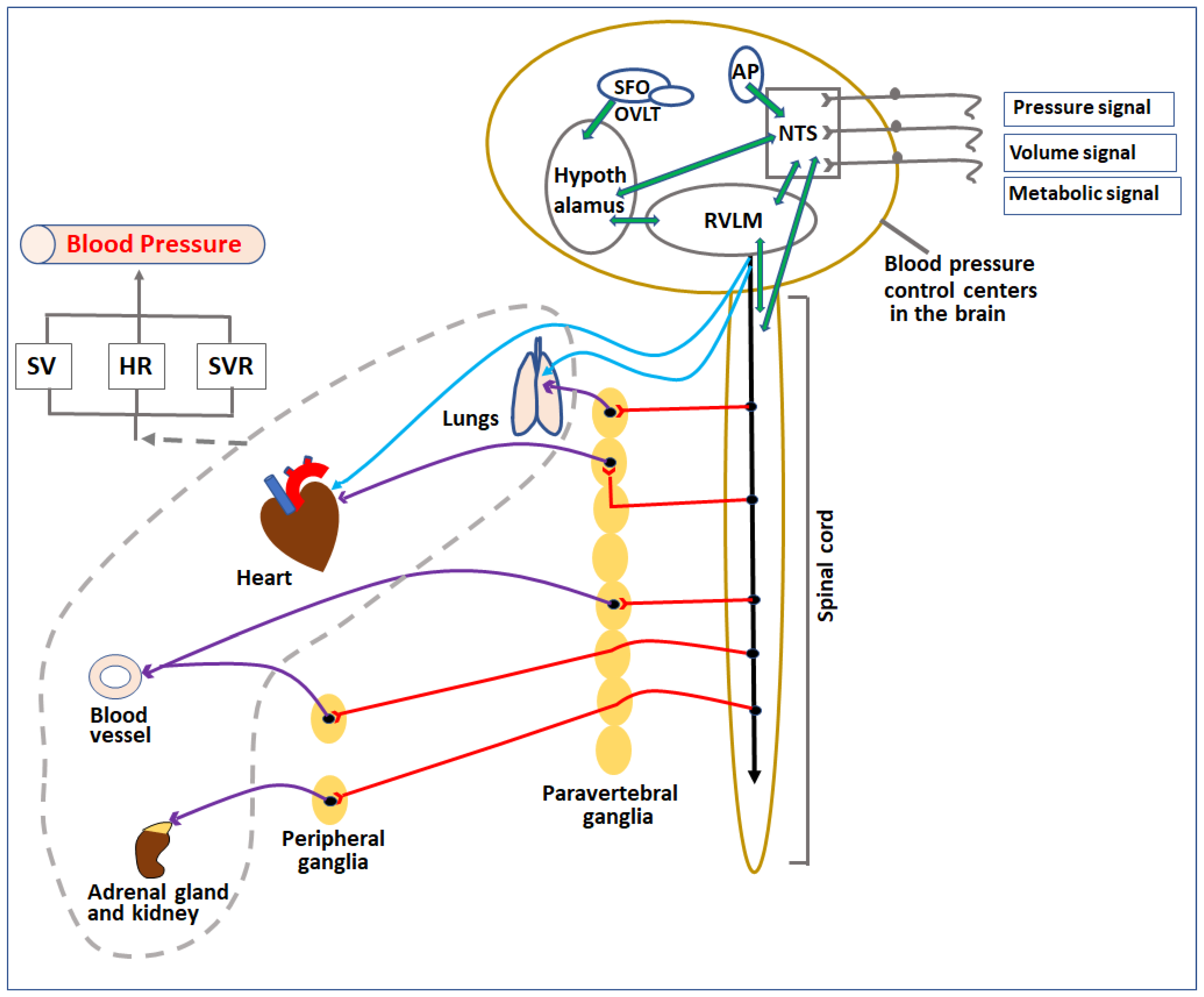

The blood pressure control systems in the body regulate these factors through various mechanisms involving neural signaling, hormonal, enzymatic, osmotic, and cellular effects to maintain/change the blood pressure according to the needs in normal as well as in disease conditions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diagrammatic representation of control centers and organs involved in regulation of blood pressure. Pressure, volume, and metabolic signals are sensed by various receptors in the body and transferred to blood pressure control centers in the CNS directly or indirectly through afferent nerves. The signals are processed among various localized sub-centers present in the brainstem, circumventricular organs, and spinal cord. Based on the signals, these centers release parasympathetic and sympathetic nerve impulses to regulate various cardiovascular organs (heart, lungs, kidney, and blood vessels) as well as adrenal glands. The overall effect of the change in activities of these organs (indicated by the broken grey line) affects the SV, HR, and SVR, which in turn regulate the blood pressure. SV—stroke volume, HR—heart rate, SVR—systemic vascular resistance, NTS—nucleus tractus solitarius, RVLM—rostral ventrolateral medulla, AP—area postrema, SFO—subfornical organ, OVLT—organum vasculosum lamina terminalis.

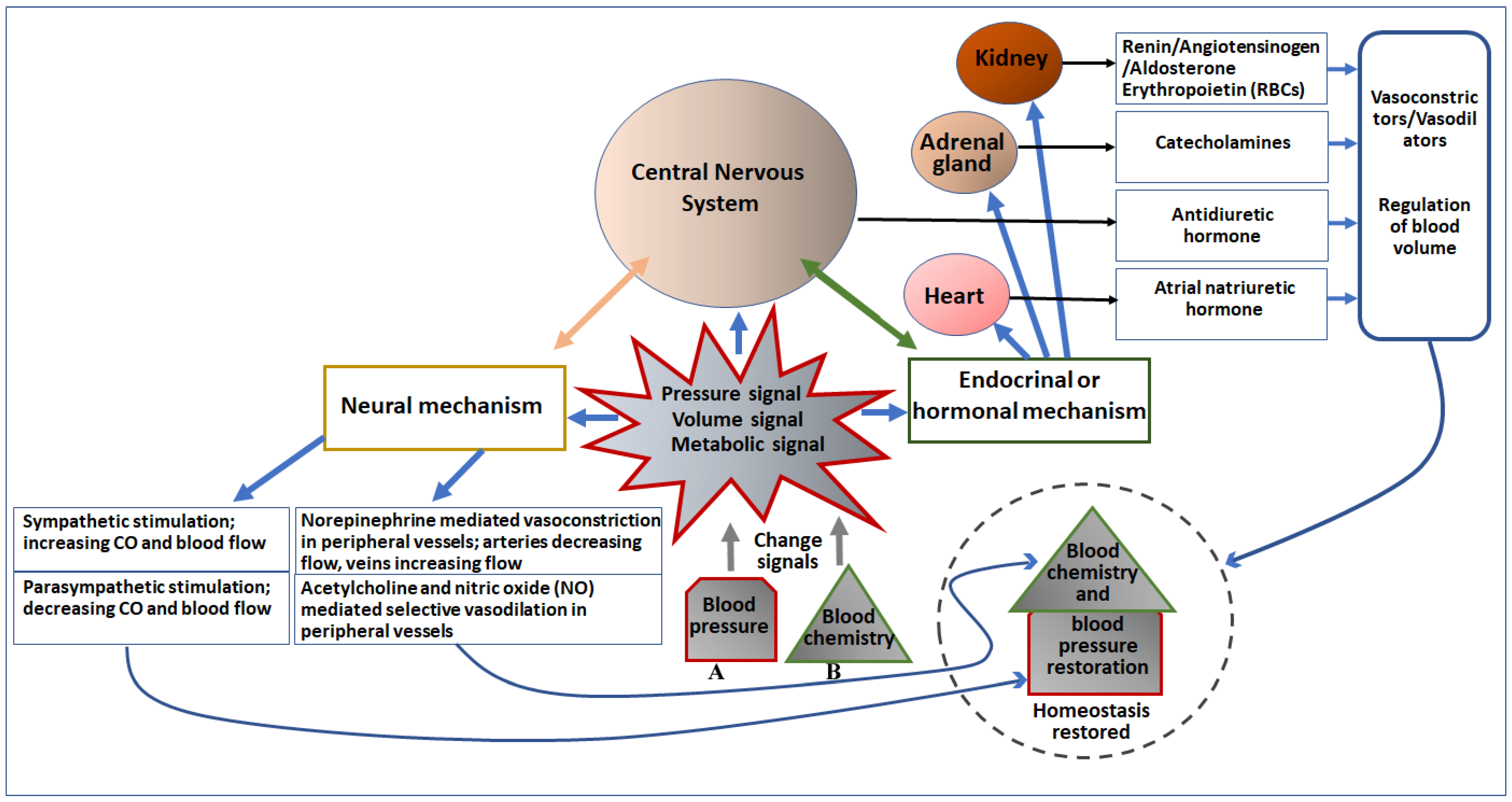

2.1. Neural Controls

Blood pressure control in our body by the neural system is highly complex. It involves coordination among peripheral autonomic nerves, the spinal cord, and the brainstem for sensing changes in baroreceptors and chemoreceptors to maintain homeostasis at normal conditions or prepare the body for fight or flight. Neural components are strategically arranged in the cardiovascular system to sense mechanical and chemical changes in the blood and send signals to the cardiovascular control center (CCC) in the brainstem. Signals are further processed and regulated by specific neuronal cells in the CCC and relay either sympathetic or parasympathetic commands to related effector organs as compensatory measures (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Diagrammatic representation of the effect of change in blood pressure (A) and blood chemistry (B) on major cardiovascular organs and the CNS, and regulation of blood pressure. Pressure, volume, and metabolic signals generated due to changes in blood pressure and chemistry primarily activate the neural as well as the endocrinal/hormonal mechanism of regulation. Both neural and endocrinal/hormonal components are connected to the CNS, which initiates neural signaling to directly control the blood pressure as well as blood chemistry, as depicted in the left portion of the figure. Moreover, the CNS (the brain) also secretes an antidiuretic hormone to regulate blood volume and chemistry. The endocrine/hormonal signaling is also mediated by the heart (secretes atrial natriuretic hormone), adrenal gland (secretes catecholamines), and kidney (secretes renin, angiotensinogen, aldosterone, and erythropoietin). These secreted factors regulate both blood chemistry as well as blood pressure (depicted in the right portion of the figure).

2.1.1. Sensory Receptors (Baroreceptors and Chemoreceptors)

Baroreceptors—Baroreceptors are stretch receptors located on the terminal arborizations of afferent nerve fibers of the autonomic peripheral nervous system. They sense the stretch stimulus in the arterial wall and relay information to specialized parts of the central nervous system, which regulates the autonomic activities of the peripheral nervous system [15][16]. Based on their functional property, they are categorized into two types, high-pressure arterial baroreceptors and low-pressure volume receptors. The aortic arch and carotid sinus of the circulatory system are equipped with high-pressure arterial baroreceptors, while atria, ventricles, and lungs have low-pressure volume receptors or cardiopulmonary receptors.

The baroreceptors in the aortic arch and carotid sinus have stretch fibers that sense the stretch stimulus in arteries and send electrical signals to the solitary nucleus of the medulla via the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) and glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX), respectively. The arterial baroreceptors instantaneously inform the nervous system about beat-to-beat stretch changes in the carotid and aortic arteries, which helps in sensing rapid changes in the blood pressure by the CNS in daily life. These baroreceptors, for instance, detect variations in artery wall stretching and send a signal to the central nervous system. The CNS senses these reflexes and then regulates activities through efferent (sympathetic and/or parasympathetic) nerves, affecting cardiac output, vasoconstriction, or vasodilation to change the SVR for blood pressure adjustment. Dysfunction in these baroreceptors compromises the blood pressure compensatory mechanisms and may lead to orthostatic hypotension, a common hypotensive disorder with aging [17].

On the other hand, the low-pressure volume or cardiopulmonary receptors are mechanoreceptors that sense changes in the blood volume and send the signal to the CNS through the vagus afferent nerve. They are present in the lungs, atria, and ventricles and can modulate central sympathetic outflow. Clinical and experimental observations suggest that the left ventricle and atria receptors are more important than other receptors for modulating cardiopulmonary reflexes [18]. In reflex to the afferent signal from these receptors, the CNS initiates the compensatory mechanisms to normalize the blood volume. For instance, in the low-volume state, the CNS relays sympathetic activity to modulate renal activities for increasing salt and water resorption to increase the blood volume and helps in increasing the heart preload and SV [19]. The activity of mechanoreceptors is returned to the baseline after arterial pressure reaches homeostasis. Hence, mechanoreceptors are essential for adjusting short-term blood pressure [20]. However, resetting these receptors’ baseline value helps them operate over a higher range of MAP and sympathetic activity during exercise and stress. The advantage of such mechano-reflex resetting is that during physiologically active behaviors (e.g., exercise or defense) where increased arterial pressure is required, they can effectively regulate the arterial pressure at a higher level [21].

Chemoreceptors—Chemoreceptors located in the carotid and aortic arteries are known as peripheral chemoreceptors, while those in the medulla oblongata are categorized as central chemoreceptors. These specific chemoreceptors are activated primarily by a decrease in PaO2 to a level of hypoxic condition or due to an increased pCO2 level (hypercapnia). Like the baroreceptors, the cranial nerves IX and X act as the afferent nerves for carotid and aortic chemoreceptors, respectively, and send the signal to the CNS. The hypoxia or hypercapnia condition to the peripheral chemoreceptors produces bradycardia, an increased respiratory rate, and alveolar ventilation, with a concurrent decrease in the blood flow to the peripheral tissues to conserve O2 [22][23]. On the other hand, tachycardia and hypertension result from hypoxia or hypercapnia sensed by the central chemoreceptors, which increases blood flow in the affected areas and thereby decreases PCO2 or increases PO2. These chemoreceptor reflexes are observed in adults; however, the role of central and peripheral chemoreceptors in the fetus is poorly understood [24]. Mostly, the net result of hypoxia or hypercapnia in the fetus is bradycardia with hypertension.

Apart from the chemoreceptors, nasopharyngeal receptors conserve the available O2 in all air-breathing vertebrates. The nasopharyngeal reflex, also known as the diving reflex, is particularly powerful in diving animals [25]. Activation of nasopharyngeal receptors leads to reflex apnea, bradycardia, and intense peripheral vasoconstriction (except in the brain and heart). Additionally, in non-diving animals, in response to stimulation of nasopharyngeal receptors by noxious substances such as smoke, the same respiratory and cardiovascular effects pattern is evoked [26]. Cessation of ventilation and O2 conservation increases the probability of survival.

A higher level of complexity arises because of the activation of reflexes from more than one type of bioreceptor in response to a particularly challenging situation. For instance, in diving animals, the first reflex after submersion is the nasopharyngeal receptor-mediated reflex, which causes apnea, bradycardia, and vasoconstriction. The resultant hypoxia, in turn, triggers the chemoreceptor-mediated reflexes. The interaction of these two types of reflexes reinforces vasoconstriction and bradycardia, along with suppression of the normal ventilatory response to the chemoreceptors’ reflex by inputs from nasopharyngeal receptors [27]. Thus, the resultant effect of cardiovascular and respiratory activities depends on the interaction of several reflexes to provide optimum adaptability in case of imminent challenges.

Besides the receptors mentioned above, some other receptors, e.g., vestibular receptors, skeletal muscle receptors, and skin nociceptors, play minor roles in regulating blood flow and pressure in specific vascular beds [28][29][30][31].

2.1.2. Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of all the nerves branching out of the central nervous system (CNS) and their ganglia (a series of clusters of neurons linked by axonal bridges). Each nerve consists of a bundle of many nerve fibers (axons) and their connective tissue coverings, while each nerve fiber is an extension of a neuron whose cell body is either within the CNS or within the ganglia of the PNS. These nerves are the workhorse of the PNS and transmit impulses from sensory receptors to and from the CNS to effector organs. The nerves which transmit impulses from sensory receptors/sense organs are known as afferent nerves, while the nerves that bring nervous information to effector organs are known as efferent nerves. A total of 43 pairs of nerves form the basis of our body’s peripheral nervous system. They are categorized as 12 pairs of cranial and 31 pairs of spinal nerves. Cranial nerves come from the brainstem or cranium, while spinal nerves emerge from the spinal cord [32]. The PNS is divided into the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and the somatic nervous system (SNS) based on their properties of controlling involuntary and voluntary activities, respectively. The ANS is instrumental in homeostatic mechanisms in the body and performs these activities through its two sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions [33].

Sympathetic division—The sympathetic division is associated with the fight-or-flight response, and the parasympathetic division is related to rest and digest-like activities. Balancing these two divisions of the ANS helps in establishing homeostasis in our body. The nerves emerging from the thoracic and upper lumbar spinal cord (thoracolumbar system) are important components of the sympathetic division. They regulate the activities of various organ systems [34]. Anatomically, nerves or neurons of these spinal regions are projected to the adjacent ganglia through the ventral spinal roots. Typically, there are 23 ganglia in the chain on either side of the spinal column (3 in the cervical region, 12 in the thoracic region, 4 in the lumbar region, and 4 in the sacral region) [34]. The cervical and sacral ganglia are not directly connected to the spinal cord through the spinal roots, but their connections are through the bridges within the chain. The nerve fiber that projects from the CNS to a sympathetic ganglion is referred to as a preganglionic fiber or neuron, and the nerve fiber projected from a ganglion to the target effector is referred to as a postganglionic fiber or neuron. The preganglionic fiber has output from the CNS to the ganglion, while the postganglionic fiber has output from the ganglion to effector organs. The preganglionic sympathetic fibers are relatively short, and they are myelinated. The postganglionic sympathetic fibers are longer because they cover the distance from the ganglion to the target effector organ and are unmyelinated.

Notably, one of the preganglionic sympathetic fibers directly projects to the adrenal medulla [35]. The chromaffin cells in the adrenal medulla are in contact with these preganglionic fibers. These cells are neurosecretory and release signaling molecules into the bloodstream. They develop from the neural crest along with the sympathetic ganglia; therefore, the adrenal medulla is also considered a sympathetic ganglion. However, the adrenal medulla uses signaling molecules rather than axons to communicate with target structures.

In response to a threat, the sympathetic system increases the heart rate and breathing rate and causes increased blood flow to the skeletal muscle while decreasing blood flow in the digestive system and increasing sweat gland secretion. Thus, it can execute an integrated response against a stimulus or threat. All these physiological changes are required to occur together in a highly synchronized manner involving activities of multiple organs at the same time for the execution of a successful “fight-or-flight” response. These responses of sympathetic division are possible due to a wide diversion of the sympathetic nerve projections, which enable each preganglionic neuron to influence different regions of the sympathetic system very broadly by acting on widely distributed organs throughout the body [36][37][38].

Parasympathetic division—It is named parasympathetic because the central neurons of this division are located on either side of the thoracolumbar region of the spinal cord. Their preganglionic neurons are in nuclei of the brainstem and the lateral horn of the sacral spinal cord; therefore, it is also referred to as the craniosacral system (or outflow) [33]. The preganglionic parasympathetic nerve fibers originate from the cranial region and the sacral region, and travel in cranial nerves and spinal nerves, respectively. The axons of these nerve fibers travel from the CNS to the terminal ganglia in proximity to (or into) the target effector. The postganglionic parasympathetic fibers project to target the effector or specific target tissue of an organ. The vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) is an important component of the parasympathetic system in regulating blood pressure by affecting heart activities directly with parasympathetic effects [39]. Neurons in the dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve and the nucleus ambiguus (both situated in the brainstem) travel through the vagus nerve and project the terminal ganglia of the thoracic (primarily influencing the heart, bronchi, and esophagus) and abdominal (primarily influencing the stomach, liver, pancreas, gall bladder, and small intestine) cavities.

Chemical signaling in the autonomic nervous system—Synapses of the autonomic system are classified as either cholinergic or adrenergic [33]. Acetylcholine (ACh) is released in the cholinergic synapses, while norepinephrine is released in the adrenergic synapses after an electrical signal is generated due to action potential in the nerve fiber. The cholinergic system has two classes of receptors: the nicotinic receptor and the muscarinic receptor, and both bind to Ach and cause changes in the target cell [33]. However, their signaling could be different because the nicotinic receptor is a ligand-gated cation channel, and the muscarinic receptor is a G protein-coupled receptor. The adrenergic system also has two types of receptors: the α-adrenergic and β-adrenergic receptors, and both types are G protein-coupled receptors. The α-adrenergic receptor and β-adrenergic receptor are further sub-grouped into α1, α2, α3, and β1, β2, respectively. Besides the higher versatility in the receptors of the adrenergic system than the cholinergic system, it also has a second signaling molecule called epinephrine (or adrenaline) [33]. The chemical difference between norepinephrine and epinephrine is that the latter has an additional methyl (CH3) group (the prefix “nor” refers to the missing methyl group). All sympathetic and parasympathetic preganglionic nerve fibers are cholinergic-type and release Ach, while all ganglionic neurons, the targets of the preganglionic nerve fibers, have nicotinic receptors because they are ligand-gated cation channels and facilitate depolarization of the postsynaptic membrane. The parasympathetic postganglionic nerve fibers are also cholinergic and release Ach, but the receptors on their targets are muscarinic receptors, which are G protein-coupled receptors. While on the other hand, sympathetic postganglionic nerve fibers are mostly adrenergic and release norepinephrine, except for fibers that project to sweat glands and blood vessels associated with skeletal muscles, which are cholinergic-type and release Ach [33].

2.1.3. Central Nervous System (CNS)

The components of the central nervous system, which are primarily involved in regulating blood pressure, are the spinal cord and the brainstem. The CNS subserves the baroreceptor, chemoreceptor, and other reflexes to regulate blood pressure and oxygenation by feedback (reflex) and/or feedforward (central command) mechanisms [40]. These two general mechanisms are not entirely autonomic but are modulated by the central command signals from the forebrain or midbrain [41]. Arterial baroreceptors in the carotid sinus and aortic arch run into the glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX) and vagus nerve (cranial nerve X), respectively. They terminate in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) in the dorsomedial medulla of the brainstem. NTS, in association with other brain centers, e.g., nucleus ambiguus, caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM), and rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), makes complex neuronal interconnections or (baro)reflex circuitry to control and regulate the efferent signals according to the situations. Second-order neurons of the NTS can connect directly to cardiac vagal motoneurons in the nucleus ambiguus or to interneurons present in the CVLM. The interneurons of the CVLM project to sympathetic premotor neurons in the RVLM. Sympathetic premotor neurons in the RVLM are tonically active. They are critical for maintenance of the sympathetic vasomotor tone and resting arterial pressure.

On the other hand, the interneurons of the CVLM are GABAergic neurons, which can inhibit the activity of sympathetic premotor neurons of the RVLM [42]. Thus, the (baro)reflex circuitry can modulate the tonic activity of sympathetic premotor neurons and permit both a reflex decrease and increase in sympathetic activity in response to altered input from the arterial baroreceptors. Moreover, some of the neurons within the baroreflex circuitry are known to receive inputs from nuclei at higher levels of the brain, e.g., periaqueductal gray (PAG) of the midbrain, dorsomedial and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus, central nucleus of the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and insular cortex [21][43]. Although the precise role of these inputs has yet to be established, it is likely that they play an important role in resetting the baroreceptor reflex during different behaviors and conditions. The afferent nerves of chemoreceptors of carotid and aortic arteries also terminate on secondary interneurons in the NTS. The NTS secondary interneurons project to several targets, e.g., respiratory neurons in the RVLM, the pre-Bötzinger complex, and dorsolateral pons [40]. The chemoreflex sympathetic excitation is mediated by the direct input from the NTS to RVLM sympathetic premotor neurons and by indirect inputs via neurons of the central respiratory network.

Inputs of reflexes from a wide range of other receptors, e.g., nasopharyngeal receptors, cardiopulmonary receptors, vestibular receptors, skeletal muscle receptors, and skin nociceptors that affect cardiovascular function, also project to the NTS, either directly or indirectly via other relay nuclei in the medulla oblongata. Moreover, inputs from some of these receptors can project directly to the RVLM, bypassing the NTS [40]. However, the inputs from all the receptors ultimately reach the sympathetic premotor neurons in the RVLM. Thus, the RVLM acts as the major site at which interactions among different inputs from receptors regulating sympathetic activity occur. Furthermore, the RVLM is equipped with subgroups of sympathetic premotor neurons that simultaneously preferentially or exclusively control different sympathetic outflows in a differential manner to various organs. For example, stimulation of baroreceptors causes vasodilation in the vascular bed of the skeletal muscle, with a modest vasodilator effect on the skin blood vessels. In contrast, stimulation of chemoreceptors evokes a powerful vasoconstrictor effect on skeletal muscle vascular beds but has a similar effect (modest vasodilation) on skin blood vessels [40]. Thus, the lower brainstem portion of the brain contains the structural centers for performing the central pathways subserving the reflexes described above. However, the regulatory centers for defending the body against a decrease in blood volume (because of hemorrhage or dehydration) are located in the forebrain and the lower brainstem.

The circumventricular organs (organum vasculosum lamina terminalis (OVLT), area postrema (AP), and subfornical organ (SFO)) in the anterior wall of the third ventricle are equipped with specific neurons, which can sense the increased levels of osmolarity (Na+), metabolites, pH, and specific cytokines, peptides, or hormones (e.g., angiotensin II) in the blood due to hemorrhage or dehydration. After sensing the signals, neurons in the OVLT and SFO relay the information to the hypothalamic supraoptic nucleus (SON) and paraventricular nucleus (PVN) using direct or indirect (via the median preoptic nucleus) connections. The OVLT, SFO, and median preoptic nucleus are collectively referred to as the lamina terminalis. In response to the low blood volume signals, these neurons trigger an increase in drinking, leading to vasopressin release from the pituitary gland and increased sympathetic activity [44]. These compensatory responses help increase fluid intake, minimize fluid loss by kidneys (vasopressin increases water reabsorption in kidneys), and increase blood pressure to restore fluid homeostasis. Similarly, leptin, a hormone derived from adipose tissue, can bind to its receptors in the SFO neurons and increase renal sympathetic nerve activity [45]. In addition, a high level of circulating proinflammatory cytokines in the blood is also known to increase blood pressure, heart rate, and sympathetic activity mediated through the SFO [46]. However, the effects of circulating leptin or cytokines are not exclusively via the SFO, and hypothalamic regions outside the circumventricular organs are also involved [47]. Both OVLT and SFO circumventricular organs are critical sites that sense the circulating factors indicating hypovolemia or dehydration and affect cardiovascular function.

2.1.4. Spinal Cord

The spinal cord is an important integrative center of sympathetic responses essential for blood pressure control [48]. The effect of the sympathetic nervous system is highly crucial in regulating blood pressure because postganglionic sympathetic nerves innervate blood vessels and affect peripheral resistance by modulating vascular smooth-muscle tone. At rest, the background level of sympathetic tone is the fundamental determinant for long-term blood pressure control. This background level is set by a central autonomic network formed among the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), the hypothalamus, and the spinal cord. Moreover, the core sympathetic network is regulated by many sensory afferent nerves that project either to the NTS or to the spinal cord (somatic and sympathetic afferents detecting chemical factors, physical factors, and metabolites during muscle stretch or tissue hypoxia) [49]. Although these characteristics of the spinal cord indicate its potential roles in sympathetic background tone setup and regulating the core sympathetic network, the spinal cord is often described as a mere relay station between the brainstem and the peripheral nervous system. Nonetheless, clinical and experimental evidence has suggested that intraspinal reflex circuits could directly and independently orchestrate reflex-mediated changes in blood pressure, especially in patients with spinal cord injuries where descending inhibitory pathways were interrupted [50]. Moreover, inflammatory conditions involving the viscera, such as inflammatory bowel disease, may cause hyperexcitability in the visceral spinal afferent [51]. Several studies have demonstrated an increased incidence of hypertension in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [52]. These observations indicate that spinal afferent hyperexcitability in these patients may contribute to hypertension via activation of the viscero-spinal sympathetic reflex circuitry. Supporting this notion, a study by Jensen et al. has shown that the risk of developing hypertension was significantly reduced in patients who had surgical colectomy compared to patients subjected to other surgical procedures [53]. Thus, the active roles of the spinal cord in sympathetic regulation of blood pressure cannot be ignored; however, more conclusive future studies using animal models are required to prove the roles of spinal afferent fibers in the development of systemic hypertension in diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease.

2.2. Hormonal (Endocrine) and Enzymatic Controls

Hormones are essential for the body’s short-, mid-, and long-term blood pressure management and regulation. Various types of hormones are involved in regulating blood pressure [54]. They influence the cardiovascular system directly to induce vasoconstriction and vasodilation for short-term blood pressure control, while they work with kidneys in managing the blood volume required for mid-term control and affect the generation of red blood cells (erythropoiesis) that changes the hematocrit volume as well as the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood required for long-term blood pressure changes [55]. Thus, the hormone (endocrine) system plays a critical role in establishing and maintaining an appropriate blood pressure by sustainably responding to either decreased or increased blood pressure. Some of the important hormones that play a role in blood pressure control are as follows.

2.2.1. Catecholamines

Catecholamines are physiologically active molecules, e.g., dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine, acting as neurotransmitters and hormones. They play vital roles in maintaining blood pressure and homeostasis through the autonomic nervous system. Catecholamines are produced in the brain and the sympathetic nerve endings and neuroendocrinal chromaffin cells of peripheral tissues (e.g., adrenal glands) [56]. They activate adrenergic receptors primarily located in multisystem smooth muscle and adipose tissue. They are well-known for the “fight-or-flight” response of the sympathetic nervous system, which results from the quick multisystem action of catecholamines [57]. Norepinephrine is important for regulating blood pressure because the adrenergic receptors (alpha-1 receptors) linked to blood vessels have a great affinity for norepinephrine and induce constriction in smooth-muscle cells of arteries [58]. Other remarkable functions of catecholamines include beta-1 receptor-mediated enhanced contraction of cardiac muscle, alpha-1 receptor-mediated contraction of the pupillary dilator muscle and piloerection, and beta-2 receptor-mediated relaxations of smooth muscle in the gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, and bronchioles [59]. In addition, epinephrine and norepinephrine regulate metabolic activities in the body, such as stimulating glycogenolysis, glucagon secretion (both via beta-2 receptors), lipolysis via beta-3 receptors, and decreasing insulin secretion via alpha-2 receptors [60][61]. Moreover, epinephrine also ameliorates type I hypersensitivity reactions [62]. Thus, catecholamines are important hormones that are essential for regulating neurovascular, cardiovascular, and metabolic activities, important for quick responses of the body in the presence of stimuli, and for adaptation in a new environment.

2.2.2. Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone–Antidiuretic Hormone System (RAAAS)

While renin is commonly referred to as a hormone, it is functionally an enzyme produced from the conversion of prorenin by juxtaglomerular cells in kidneys [63]. Prorenin is also produced and secreted in blood circulation by the adrenal gland and gonads. The amount of prorenin in circulation is about ten times higher than renin, which makes prorenin sufficiently available for conversion into renin [64]. The production and release of renin from juxtaglomerular cells are in response to multiple stimuli, including hypotension, decreased pulse amplitude, excessive urine production, or in response to sympathetic activity [65]. Circulating renin acts on angiotensinogen, a pre-pro-hormone produced by the liver, and converts it to angiotensin I (Ang I). Therefore, renin is also known as angiotensinogenase. Further, enzymatic conversion of Ang I to angiotensin II (Ang II) is carried out by the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) [66]. ACE is found in the lungs, and its activity depends on the amount of fluid passing through pulmonary tissues. Ang II is the most important hormone in the RAAAS as it has multiple effects at the core of this system. It controls blood flow and blood pressure by promoting vasoconstriction. It stimulates aldosterone secretion by the adrenal cortex and releases antidiuretic hormone (ADH) or vasopressin from the pituitary gland [67]. Ang II also stimulates thirst at the level of the hypothalamus to increase the consumption of fluids and thus regulates blood volume. Moreover, Ang II can bind to AT1 receptors on juxtaglomerular cells and inhibit renin production by a negative feedback mechanism [67].

Aldosterone is a steroid hormone produced in the mitochondria of cells in a distinct region of the adrenal cortex, the zona glomerulosa [68]. Aldosterone is normally released at the basal level; however, in the presence of signals from regulatory hormones, its release rate is enhanced or inhibited. Ang II and high serum potassium are major aldosterone release stimuli [68]. Ang II binding to AT1 receptors on zona glomerulosa cells induces the closure of potassium channels, resulting in the flow of ions that depolarize the membrane and cause the opening of voltage-gated calcium channels. The calcium influx generated due to the opening of the calcium channels initiates aldosterone secretion from zona glomerulosa cells. A breakdown product of Ang II, known as Ang III, can also stimulate aldosterone release with equal efficacy as Ang II [69]. Sympathetic reflexes due to stress or baroreceptors in the carotid artery due to low blood pressure are also known to increase the rate of aldosterone [70]. Once released, aldosterone can bind to its receptors on the membrane surface and in the cytoplasm; however, generally, it exerts its effects through cytoplasmic receptors by altering transcription [71]. Aldosterone is involved in multiple activities, such as promoting sodium retention and inhibiting potassium retention by the kidneys, as well as stimulating sodium uptake by the colon. In the kidneys, it increases sodium reuptake in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle, in the distal convoluted tubule, and in the collecting duct by upregulating amiloride-sensitive sodium channels and the sodium–potassium–chloride cotransporter 2 (NKCC2) [68]. Amiloride-sensitive sodium channels assist in the passive movement of sodium along its concentration gradient, while NKCC2 uses the concentration gradient of sodium to transport sodium, potassium, and chloride from the filtrate into epithelial tubule cells exposed to the lumen of the nephron [72]. Aldosterone also increases the number and activity of sodium–potassium–ATPase pumps present in these tubule cells and helps exchange intracellular sodium for extracellular potassium and pump sodium out into the interstitial fluid [73]. Chloride that enters the tubule cells via NKCC2 also reaches the interstitial fluid either through chloride channels or co-transported with potassium using the high intracellular concentration of potassium. From interstitial fluid, sodium, chloride, and potassium are reabsorbed by peritubular capillaries. Aldosterone also increases the expression of potassium channels on the apical membrane of epithelial tubule cells, which allows the accumulation of intracellular potassium within these tubule cells. Thus, aldosterone facilitates the sodium reabsorption and decreases reabsorption of potassium in the kidney. Ang II also drives the secretion of ADH or vasopressin, which play an important role in water reabsorption in kidneys. It is secreted from the posterior pituitary, and its secretion is also directly governed by the hypothalamus. ADH is secreted when high extracellular sodium is detected by hypothalamic osmoreceptors. Moreover, the hypothalamus can also induce ADH secretion when it receives signals of decreased arterial blood volume, even if plasma osmolarity is low (e.g., during a period of hyponatremia) [74]. ADH has no basal level of secretion, but it is released into open circulation only after it is induced by factors or signals. The central effects of ADH include promoting thirst to increase water consumption and raising the volume of water in blood, increasing water reabsorption in the kidneys, and minimizing water loss through urine. ADH targets epithelial cells lining the distal convoluted tubule as well as the collecting duct in kidneys. It stimulates transcription and translocation of aquaporins to the apical membranes of these epithelial cells [74]. Aquaporins increase the ability of water to flow from filtrate into the interstitial space along its osmotic gradient. ADH can also change the permeability of the collecting duct to urea and helps in the osmotic gradient drawing water into the interstitial space. Water from the interstitial space is absorbed by peritubular capillaries, thus increasing the water volume in blood. Moreover, ADH enhances sodium reabsorption in the ascending limb of the loop of Henle by increasing the activity of NKCC2 through phosphorylation [75]. The increased sodium reabsorption enhances the osmotic gradient that enables water reabsorption.

Although Ang II regulates the release of aldosterone and ADH, they operate independently and often synergistically. For example, aldosterone contributes to the osmotic gradient by promoting sodium retention in the kidneys, ultimately helping ADH in water retention. While in the case of hypernatremia, the high osmolarity in the extracellular fluid drives the release of ADH without promoting the release of aldosterone. Thus, the RAAAS raises sodium and water reabsorption in the kidneys to increase blood volume and, consequently, blood pressure.

Besides blood pressure regulation, recent studies have shown the involvement of RAAAS molecules in various pathogenesis, such as arterial hypertension, heart failure, fibrotic end-organ damage, etc. For example, approximately 10% of cases of arterial hypertension are associated with dysregulated autonomous aldosterone production caused by renal, cardiovascular, neurological, and endocrine diseases [76][77][78][79]. The clinical trials: randomized Aldactone evaluation study (RALES) and eplerenone post-acute myocardial infarction heart and survival study (EPHESUS), evaluated the role of mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) antagonism in patients with heart failure and patients with acute myocardial infarction, respectively. These studies’ findings showed substantially reduced morbidity and mortality risks in patients treated with MR antagonists spironolactone or eplerenone [80][81], which were associated with beyond their diuretic and potassium-sparing effects [82]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis study encompassing clinical studies related to the effect of ACE inhibitors in cardiac hypertrophy demonstrated that ACE drugs were better than β-blockers and diuretics in reducing the left ventricular mass index [83]. Moreover, the renoprotective effects of ACE and angiotensin receptor inhibitors in hypertensive and diabetic patients with kidney failure have been demonstrated [84]. These findings indicate that the components of RAAAS contribute not only to blood pressure regulation but also to cardiovascular function.

2.2.3. Natriuretic Peptides

Natriuretic peptides are another hormone in our body that functions almost exactly opposite to aldosterone and ADH [85]. Mainly, they are of two types: atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), which have similar roles in blood pressure regulation. ANP is produced in the right atrium of the heart. Its production is induced upon overstretching of the atrium or when baroreceptors in the aorta and carotid artery signal excessive hypertension. ANP inhibits aldosterone release and acts as an inhibitor of ADH action in the kidneys, decreasing sodium and water retention. The lower sodium and water retention leads to a lower blood volume and blood pressure. Moreover, ANP also affects the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine to reduce vasoconstriction and blood pressure. The ventricles primarily release BNP in response to stretching, affecting blood volume and blood pressure, similar to ANP [86].

2.2.4. Erythropoietin

The kidneys start a multi-week process of boosting the number and longevity of red blood cells in response to a drop in blood pressure or volume if the short-term and mid-term responses cannot deliver processed oxygen to tissues where it is needed [87]. This is achieved through increased erythropoietin (EPO) production by the kidneys in hypoxic conditions. EPO is a hormone produced by the peritubular cells of the kidney that stimulates red blood cell production [88]. Normally, a basal release of EPO is required for maintaining an appropriate number of red blood cells in the blood and providing an average life span of about four months. The upregulated production of EPO in the kidney increases the number of RBCs in the blood, which increases both blood volume as well as its oxygen-carrying capacity; moreover, it also increases the average lifespan of RBCs [89]. Therefore, upon sensing low blood pressure, kidneys raise the blood pressure by increasing blood volume through increased EPO production and boosting hematocrit levels under hypoxia.

2.3. Vascular Endothelial Cell-Mediated Controls

Endothelial cells line all blood vessels and are critical regulators of vascular tone and blood pressure by releasing specific vasoactive factors, e.g., nitric oxide, prostacyclin, and endothelins [90]. Disruption of endothelial function can alter the release of these vasoactive factors and increase vascular tone and hypertension.

Nitric oxide (NO) is released from endothelial cells and is also known as an endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF). It is a free radical gas with a very short half-life [91]. The level of NO release changes in response to blood flow-induced shear stress and activation of various receptors. In addition to vasodilatation, NO also affects myocardial contractility and has anti-thrombotic, leukocyte adhesion inhibition effects [92], directly or indirectly influencing blood pressure. The pharmacological inhibition of NO causes an enhanced vasoconstrictor effect of Ang II, decreased cardiac output, and increased systemic and pulmonary arterial blood pressure.

Prostacyclin is a potent endogenous platelet aggregation inhibitor that inhibits platelet activation induced by various stimulants. It also acts as a potent vasodilator and inhibits the growth of vascular smooth-muscle cells [93].

Endothelial cells produce three different types of endothelins (ET-1, ET-2, and ET-3). They are vasoactive polypeptides and belong to the same family, but each encodes different genes. ET-1 is considered one of the most potent vasoconstrictors ever discovered [94][95]. They can bind to two different types of ET receptors, ETARs and ETBRs, and initiate different levels and categories of downstream activities. Activating ETBRs leads to decreased arterial pressure and natriuresis through effects on the adrenal gland and heart (negative inotropy), decreasing sympathetic activity, and increasing systemic vasodilatation [96]. Conversely, activation of ETARs causes increased sympathetic activity with increased sodium retention, positive inotropy of the heart, increased catecholamine release, and increased systemic vasoconstriction and arterial pressure [97][98].

References

- Roman, M.J.; Devereux, R.B. Association of central and peripheral blood pressures with intermediate cardiovascular phenotypes. Hypertension 2014, 63, 1148–1153.

- Li, W.Y.; Wang, X.H.; Lu, L.C.; Li, H. Discrepancy of blood pressure between the brachial artery and radial artery. World J. Emerg. Med. 2013, 4, 294–297.

- Kim, H.; Kim, I.C.; Hwang, J.; Lee, C.H.; Cho, Y.K.; Park, H.S.; Chung, J.W.; Nam, C.W.; Han, S.; Hur, S.H. Features and implications of higher systolic central than peripheral blood pressure in patients at very high risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2021, 35, 994–1002.

- Terentes-Printzios, D.; Gardikioti, V.; Vlachopoulos, C. Central Over Peripheral Blood Pressure: An Emerging Issue in Hypertension Research. Heart. Lung. Circ. 2021, 30, 1667–1674.

- Flores Geronimo, J.; Corvera Poire, E.; Chowienczyk, P.; Alastruey, J. Estimating Central Pulse Pressure from Blood Flow by Identifying the Main Physical Determinants of Pulse Pressure Amplification. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 608098.

- Kelly, R.P.; Gibbs, H.H.; O’Rourke, M.F.; Daley, J.E.; Mang, K.; Morgan, J.J.; Avolio, A.P. Nitroglycerin has more favourable effects on left ventricular afterload than apparent from measurement of pressure in a peripheral artery. Eur. Heart J. 1990, 11, 138–144.

- Avolio, A.P.; Van Bortel, L.M.; Boutouyrie, P.; Cockcroft, J.R.; McEniery, C.M.; Protogerou, A.D.; Roman, M.J.; Safar, M.E.; Segers, P.; Smulyan, H. Role of pulse pressure amplification in arterial hypertension: Experts’ opinion and review of the data. Hypertension 2009, 54, 375–383.

- Sun, J.; Yuan, J.; Li, B. SBP Is Superior to MAP to Reflect Tissue Perfusion and Hemodynamic Abnormality Perioperatively. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 705558.

- Curtis, L.J.; Rabkin, D.C.; Cabreriza, S.E.; Spotnitz, H.M. Relation between mean arterial pressure (MAP) and cardiac output (CO) in open chest pigs. ASAIO J. 2003, 49, 173.

- Grand, J.; Wiberg, S.; Kjaergaard, J.; Wanscher, M.; Hassager, C. Increasing mean arterial pressure or cardiac output in comatose out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients undergoing targeted temperature management: Effects on cerebral tissue oxygenation and systemic hemodynamics. Resuscitation 2021, 168, 199–205.

- Berner, M.; Oberhansli, I.; Rouge, J.C.; Jaccard, C.; Friedli, B. Chronotropic and inotropic supports are both required to increase cardiac output early after corrective operations for tetralogy of Fallot. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1989, 97, 297–302.

- Tanigawa, T.; Yano, M.; Kohno, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Hisaoka, T.; Ono, K.; Ueyama, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Hisamatsu, Y.; Ohkusa, T.; et al. Mechanism of preserved positive lusitropy by cAMP-dependent drugs in heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000, 278, H313–H320.

- Raff, G.L.; Glantz, S.A. Volume loading slows left ventricular isovolumic relaxation rate. Evidence of load-dependent relaxation in the intact dog heart. Circ. Res. 1981, 48, 813–824.

- Sloop, G.D.; Weidman, J.J.; St Cyr, J.A. The systemic vascular resistance response: A cardiovascular response modulating blood viscosity with implications for primary hypertension and certain anemias. Ther. Adv. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 9, 403–411.

- Thrasher, T.N. Baroreceptors, baroreceptor unloading, and the long-term control of blood pressure. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005, 288, R819–R827.

- Thrasher, T.N. Baroreceptors and the long-term control of blood pressure. Exp. Physiol. 2004, 89, 331–335.

- Low, P.A.; Tomalia, V.A. Orthostatic Hypotension: Mechanisms, Causes, Management. J. Clin. Neurol. 2015, 11, 220–226.

- Minisi, A.J. Vagal cardiopulmonary reflexes after total cardiac deafferentation. Circulation 1998, 98, 2615–2620.

- Sata, Y.; Head, G.A.; Denton, K.; May, C.N.; Schlaich, M.P. Role of the Sympathetic Nervous System and Its Modulation in Renal Hypertension. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 82.

- Mahdi, A.; Sturdy, J.; Ottesen, J.T.; Olufsen, M.S. Modeling the afferent dynamics of the baroreflex control system. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013, 9, e1003384.

- Dampney, R.A.L. Resetting of the Baroreflex Control of Sympathetic Vasomotor Activity during Natural Behaviors: Description and Conceptual Model of Central Mechanisms. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 461.

- Guyenet, P.G. Regulation of breathing and autonomic outflows by chemoreceptors. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 1511–1562.

- Prabhakar, N.R.; Peng, Y.J. Peripheral chemoreceptors in health and disease. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2004, 96, 359–366.

- Purves, M.J. Chemoreceptors and their reflexes with special reference to the fetus and newborn. J. Dev. Physiol. 1981, 3, 21–57.

- Panneton, W.M.; Gan, Q. The Mammalian Diving Response: Inroads to Its Neural Control. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 524.

- Sekizawa, S.I.; Tsubone, H. Nasal receptors responding to noxious chemical irritants. Respir. Physiol. 1994, 96, 37–48.

- Panneton, W.M.; Gan, Q.; Le, J.; Livergood, R.S.; Clerc, P.; Juric, R. Activation of brainstem neurons by underwater diving in the rat. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 111.

- Fahim, M. Cardiovascular sensory receptors and their regulatory mechanisms. Indian J. Physiol. Pharm. 2003, 47, 124–146.

- Jin, G.S.; Li, X.L.; Jin, Y.Z.; Kim, M.S.; Park, B.R. Role of peripheral vestibular receptors in the control of blood pressure following hypotension. Korean J. Physiol. Pharm. 2018, 22, 363–368.

- Murphy, M.N.; Mizuno, M.; Mitchell, J.H.; Smith, S.A. Cardiovascular regulation by skeletal muscle reflexes in health and disease. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, H1191–H1204.

- Sacco, M.; Meschi, M.; Regolisti, G.; Detrenis, S.; Bianchi, L.; Bertorelli, M.; Pioli, S.; Magnano, A.; Spagnoli, F.; Giuri, P.G.; et al. The relationship between blood pressure and pain. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2013, 15, 600–605.

- Fahmy, L.M.; Chen, Y.; Xuan, S.; Haacke, E.M.; Hu, J.; Jiang, Q. All Central Nervous System Neuro- and Vascular-Communication Channels Are Surrounded with Cerebrospinal Fluid. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 614636.

- McCorry, L.K. Physiology of the autonomic nervous system. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2007, 71, 78.

- Bankenahally, R.; Krovvidi, H. Autonomic nervous system: Anatomy, physiology, and relevance in anaesthesia and critical care medicine. BJA Educ. 2016, 16, 381–387.

- Lumb, R.; Tata, M.; Xu, X.; Joyce, A.; Marchant, C.; Harvey, N.; Ruhrberg, C.; Schwarz, Q. Neuropilins guide preganglionic sympathetic axons and chromaffin cell precursors to establish the adrenal medulla. Development 2018, 145, dev.162552.

- Ernsberger, U.; Deller, T.; Rohrer, H. The sympathies of the body: Functional organization and neuronal differentiation in the peripheral sympathetic nervous system. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 386, 455–475.

- Gilbey, M.P.; Spyer, K.M. Essential organization of the sympathetic nervous system. Baillieres Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1993, 7, 259–278.

- Szulczyk, P. Functional organization of the sympathetic nervous system. Acta Physiol. Pol. 1981, 32, 155–157.

- Breit, S.; Kupferberg, A.; Rogler, G.; Hasler, G. Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 44.

- Dampney, R.A. Central neural control of the cardiovascular system: Current perspectives. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2016, 40, 283–296.

- Spyer, K.M.; Lambert, J.H.; Thomas, T. Central nervous system control of cardiovascular function: Neural mechanisms and novel modulators. Clin. Exp. Pharm. Physiol. 1997, 24, 743–747.

- Tjen, A.L.S.C.; Guo, Z.L.; Li, M.; Longhurst, J.C. Medullary GABAergic mechanisms contribute to electroacupuncture modulation of cardiovascular depressor responses during gastric distention in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2013, 304, R321–R332.

- Zanutto, B.S.; Valentinuzzi, M.E.; Segura, E.T. Neural set point for the control of arterial pressure: Role of the nucleus tractus solitarius. Biomed. Eng. Online 2010, 9, 4.

- Boone, M.; Deen, P.M.T. Physiology and pathophysiology of the vasopressin-regulated renal water reabsorption. Pflügers Arch. -Eur. J. Physiol. 2008, 456, 1005–1024.

- Harlan, S.M.; Rahmouni, K. Neuroanatomical determinants of the sympathetic nerve responses evoked by leptin. Clin. Auton. Res. 2013, 23, 1–7.

- Wei, S.G.; Zhang, Z.H.; Beltz, T.G.; Yu, Y.; Johnson, A.K.; Felder, R.B. Subfornical organ mediates sympathetic and hemodynamic responses to blood-borne proinflammatory cytokines. Hypertension 2013, 62, 118–125.

- Di Spiezio, A.; Sandin, E.S.; Dore, R.; Muller-Fielitz, H.; Storck, S.E.; Bernau, M.; Mier, W.; Oster, H.; Johren, O.; Pietrzik, C.U.; et al. The LepR-mediated leptin transport across brain barriers controls food reward. Mol. Metab. 2018, 8, 13–22.

- Minic, Z.; O’Leary, D.S.; Reynolds, C.A. Spinal Reflex Control of Arterial Blood Pressure: The Role of TRP Channels and Their Endogenous Eicosanoid Modulators. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 838175.

- Spencer, N.J.; Kyloh, M.; Duffield, M. Identification of different types of spinal afferent nerve endings that encode noxious and innocuous stimuli in the large intestine using a novel anterograde tracing technique. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112466.

- Ozdemir, R.A.; Perez, M.A. Afferent input and sensory function after human spinal cord injury. J. Neurophysiol. 2018, 119, 134–144.

- Moynes, D.M.; Lucas, G.H.; Beyak, M.J.; Lomax, A.E. Effects of inflammation on the innervation of the colon. Toxicol. Pathol. 2014, 42, 111–117.

- Czubkowski, P.; Osiecki, M.; Szymańska, E.; Kierkuś, J. The risk of cardiovascular complications in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 20, 481–491.

- Jensen, A.B.; Ajslev, T.A.; Brunak, S.; Sorensen, T.I. Long-term risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease after removal of the colonic microbiota by colectomy: A cohort study based on the Danish National Patient Register from 1996 to 2014. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008702.

- Chopra, S.; Baby, C.; Jacob, J.J. Neuro-endocrine regulation of blood pressure. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 15 (Suppl. S4), S281–S288.

- Emamian, M.; Hasanian, S.M.; Tayefi, M.; Bijari, M.; Movahedian Far, F.; Shafiee, M.; Avan, A.; Heidari-Bakavoli, A.; Moohebati, M.; Ebrahimi, M.; et al. Association of hematocrit with blood pressure and hypertension. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2017, 31.

- Wurtman, R.J. Catecholamines. N. Engl. J. Med. 1965, 273, 637–646.

- Slotkin, T.A. Development of the Sympathoadrenal Axis. In Developmental Neurobiology of the Autonomic Nervous System; Gootman, P.M., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 1986; pp. 69–96.

- Graham, R.M.; Perez, D.M.; Hwa, J.; Piascik, M.T. alpha 1-adrenergic receptor subtypes. Molecular structure, function, and signaling. Circ. Res. 1996, 78, 737–749.

- Paravati, S.R.A.; Warrington, S.J. Physiology, Catecholamines; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507716/ (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Sprague, J.E.; Arbelaez, A.M. Glucose counterregulatory responses to hypoglycemia. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Rev. 2011, 9, 463–473.

- Roh, E.; Song, D.K.; Kim, M.-S. Emerging role of the brain in the homeostatic regulation of energy and glucose metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e216.

- Frith, K.; Smith, J.; Joshi, P.; Ford, L.S.; Vale, S. Updated anaphylaxis guidelines: Management in infants and children. Aust. Prescr. 2021, 44, 91–95.

- Hsueh, W.A.; Baxter, J.D. Human prorenin. Hypertension 1991, 17, 469–477.

- Nabi, A.H.M.N.; Suzuki, F. Biochemical properties of renin and prorenin binding to the (pro)renin receptor. Hypertens. Res. 2010, 33, 91–97.

- Aldehni, F.; Tang, T.; Madsen, K.; Plattner, M.; Schreiber, A.; Friis, U.G.; Hammond, H.K.; Han, P.L.; Schweda, F. Stimulation of renin secretion by catecholamines is dependent on adenylyl cyclases 5 and 6. Hypertension 2011, 57, 460–468.

- Chappell, M.C.; Marshall, A.C.; Alzayadneh, E.M.; Shaltout, H.A.; Diz, D.I. Update on the Angiotensin converting enzyme 2-Angiotensin (1-7)-MAS receptor axis: Fetal programing, sex differences, and intracellular pathways. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 4, 201.

- Forrester, S.J.; Booz, G.W.; Sigmund, C.D.; Coffman, T.M.; Kawai, T.; Rizzo, V.; Scalia, R.; Eguchi, S. Angiotensin II Signal Transduction: An Update on Mechanisms of Physiology and Pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 1627–1738.

- Tsilosani, A.; Gao, C.; Zhang, W. Aldosterone-Regulated Sodium Transport and Blood Pressure. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 770375.

- Yatabe, J.; Yoneda, M.; Yatabe, M.S.; Watanabe, T.; Felder, R.A.; Jose, P.A.; Sanada, H. Angiotensin III stimulates aldosterone secretion from adrenal gland partially via angiotensin II type 2 receptor but not angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 1582–1588.

- Goswami, N.; Blaber, A.P.; Hinghofer-Szalkay, H.; Convertino, V.A. Lower Body Negative Pressure: Physiological Effects, Applications, and Implementation. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 807–851.

- Boldyreff, B.; Wehling, M. Aldosterone: Refreshing a slow hormone by swift action. News Physiol. Sci. 2004, 19, 97–100.

- Castrop, H.; Schiessl, I.M. Physiology and pathophysiology of the renal Na-K-2Cl cotransporter (NKCC2). Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2014, 307, F991–F1002.

- Salyer, S.A.; Parks, J.; Barati, M.T.; Lederer, E.D.; Clark, B.J.; Klein, J.D.; Khundmiri, S.J. Aldosterone regulates Na(+), K(+) ATPase activity in human renal proximal tubule cells through mineralocorticoid receptor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1833, 2143–2152.

- Zieg, J. Pathophysiology of Hyponatremia in Children. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 213.

- Ares, G.R.; Caceres, P.S.; Ortiz, P.A. Molecular regulation of NKCC2 in the thick ascending limb. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2011, 301, F1143–F1159.

- Lifton, R.P.; Gharavi, A.G.; Geller, D.S. Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell 2001, 104, 545–556.

- Martins, L.C.; Figueiredo, V.N.; Quinaglia, T.; Boer-Martins, L.; Yugar-Toledo, J.C.; Martin, J.F.; Demacq, C.; Pimenta, E.; Calhoun, D.A.; Moreno, H., Jr. Characteristics of resistant hypertension: Ageing, body mass index, hyperaldosteronism, cardiac hypertrophy and vascular stiffness. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2011, 25, 532–538.

- Calhoun, D.A.; Sharma, K. The role of aldosteronism in causing obesity-related cardiovascular risk. Cardiol. Clin. 2010, 28, 517–527.

- Conn, J.W. Aldosterone in clinical medicine; past, present, and future. AMA Arch. Intern. Med. 1956, 97, 135–144.

- Pitt, B.; Zannad, F.; Remme, W.J.; Cody, R.; Castaigne, A.; Perez, A.; Palensky, J.; Wittes, J. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 709–717.

- Pitt, B.; Remme, W.; Zannad, F.; Neaton, J.; Martinez, F.; Roniker, B.; Bittman, R.; Hurley, S.; Kleiman, J.; Gatlin, M.; et al. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1309–1321.

- Rossignol, P.; Menard, J.; Fay, R.; Gustafsson, F.; Pitt, B.; Zannad, F. Eplerenone survival benefits in heart failure patients post-myocardial infarction are independent from its diuretic and potassium-sparing effects. Insights from an EPHESUS (Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study) substudy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 1958–1966.

- Schmieder, R.E.; Martus, P.; Klingbeil, A. Reversal of left ventricular hypertrophy in essential hypertension. A meta-analysis of randomized double-blind studies. JAMA 1996, 275, 1507–1513.

- Viberti, G.; Wheeldon, N.M.; MicroAlbuminuria Reduction With, V.S.I. Microalbuminuria reduction with valsartan in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A blood pressure-independent effect. Circulation 2002, 106, 672–678.

- Johnston, C.I.; Hodsman, P.G.; Kohzuki, M.; Casley, D.J.; Fabris, B.; Phillips, P.A. Interaction between atrial natriuretic peptide and the renin angiotensin aldosterone system. Endogenous antagonists. Am. J. Med. 1989, 87, 24S–28S.

- Lee, N.S.; Daniels, L.B. Current Understanding of the Compensatory Actions of Cardiac Natriuretic Peptides in Cardiac Failure: A Clinical Perspective. Card. Fail. Rev. 2016, 2, 14–19.

- Atsma, F.; Veldhuizen, I.; de Kort, W.; van Kraaij, M.; Pasker-de Jong, P.; Deinum, J. Hemoglobin level is positively associated with blood pressure in a large cohort of healthy individuals. Hypertension 2012, 60, 936–941.

- Schoener, B.; Borger, J. Erythropoietin Stimulating Agents; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022.

- Suresh, S.; Rajvanshi, P.K.; Noguchi, C.T. The Many Facets of Erythropoietin Physiologic and Metabolic Response. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1534.

- Sandoo, A.; van Zanten, J.J.; Metsios, G.S.; Carroll, D.; Kitas, G.D. The endothelium and its role in regulating vascular tone. Open Cardiovasc. Med. J. 2010, 4, 302–312.

- Loscalzo, J. The identification of nitric oxide as endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 100–103.

- Raij, L. Nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of cardiac disease. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2006, 8, 30–39.

- Katusic, Z.S.; Santhanam, A.V.; He, T. Vascular effects of prostacyclin: Does activation of PPARdelta play a role? Trends Pharm. Sci. 2012, 33, 559–564.

- Yanagisawa, M.; Masaki, T. Molecular biology and biochemistry of the endothelins. Trends Pharm. Sci. 1989, 10, 374–378.

- Davenport, A.P.; Maguire, J.J. Endothelin. Handb. Exp. Pharm. 2006, 176/I, 295–329.

- Ribeiro-Oliveira, A., Jr.; Nogueira, A.I.; Pereira, R.M.; Boas, W.W.; Dos Santos, R.A.; Simoes e Silva, A.C. The renin-angiotensin system and diabetes: An update. Vasc. Health. Risk. Manag. 2008, 4, 787–803.

- Iwasaki, H.; Eguchi, S.; Ueno, H.; Marumo, F.; Hirata, Y. Endothelin-mediated vascular growth requires p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase and p70 S6 kinase cascades via transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor. Endocrinology 1999, 140, 4659–4668.

- Robin, P.; Boulven, I.; Desmyter, C.; Harbon, S.; Leiber, D. ET-1 stimulates ERK signaling pathway through sequential activation of PKC and Src in rat myometrial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2002, 283, C251–C260.

More

Information

Subjects:

Primary Health Care

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

3.3K

Entry Collection:

Hypertension and Cardiovascular Diseases

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

10 Feb 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No