Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Feng, Z.; Su, X.; Wang, T.; Sun, X.; Yang, H.; Guo, S. Microspheres for Bone Tissue Engineering. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40985 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Feng Z, Su X, Wang T, Sun X, Yang H, Guo S. Microspheres for Bone Tissue Engineering. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40985. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Feng, Ziyi, Xin Su, Ting Wang, Xiaoting Sun, Huazhe Yang, Shu Guo. "Microspheres for Bone Tissue Engineering" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40985 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Feng, Z., Su, X., Wang, T., Sun, X., Yang, H., & Guo, S. (2023, February 08). Microspheres for Bone Tissue Engineering. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40985

Feng, Ziyi, et al. "Microspheres for Bone Tissue Engineering." Encyclopedia. Web. 08 February, 2023.

Copy Citation

Bone defects have caused immense healthcare concerns and economic burdens throughout the world. Traditional autologous allogeneic bone grafts have many drawbacks, so the emergence of bone tissue engineering brings new hope. Bone tissue engineering is an interdisciplinary biomedical engineering method that involves scaffold materials, seed cells, and “growth factors”. Microspheres are structures with diameters ranging from 1 to 1000 µm that can be used as supports for cell growth, either in the form of a scaffold or in the form of a drug delivery system.

microspheres

bone tissue engineering

organoid

1. Introduction

Bone defects cause immense economic and healthcare concerns throughout the world. Reparation of large bone defects, as well as the restoration of the anatomical structure, appearance, and function of the injured area, has presented major difficulties [1]. At present, autologous and allogeneic bone transplantation remain the “gold standard” of bone substitution therapy in clinics. However, the drawbacks are numerous and well-known. Patients of autologous bone transplantation must undergo additional surgery, and there is a limited amount of autologous material, which in some cases may be insufficient for large-area bone defects. Additionally, there is a high incidence rate of complications such as fractures, nonunion, and infection after allogeneic bone transplantation. Therefore, it is necessary to devise new methods for engineering tissues that mimic native bone [2].

Bone tissue engineering is an interdisciplinary biomedical engineering method that can provide solutions to these complications, as it can act as an alternative to tissue transplantation [3]. This method involves the separation, cultivation, and expansion of autologous high-concentration cells in vitro, then their implantation on natural or synthetic cell scaffolds, or into the bone defect site [4]. With the gradual degradation of biomaterials, the implanted cells proliferate and differentiate, forming new bone tissue. This, in turn, helps to retain, maintain, and improve the functionality of damaged sites. Engineered bone tissues have the possibility to not only exert these functions at the time of treatment but also to continue the formation of functional tissue as needed after implantation and to further mature in situ [5]. The three elements of bone tissue engineering are “scaffold materials”, “seed cells”, and “growth factors”, the last of which can promote the growth and differentiation of seed cells [6][7].

Cells applied in the reconstruction of tissues and organs are collectively referred to as seed cells. In recent years, MSCs have been widely studied for use as seed cells in bone tissue engineering. MSCs, which were discovered by Friendenstein et al. in 1968, are widely distributed in almost all tissues of both fetuses and adults, including bone marrow, blood, the umbilical cord, umbilical cord blood, placenta, fat, the amniotic membrane, amniotic fluid, dental pulp, skin, and menstrual blood [8][9]. Bone marrow and adipose tissue are the most common cell sources of MSCs. MSCs not only have the potential of multi-directional differentiation, but in recent years, studies have shown that MSCs can promote vascular regeneration [10], reduce apoptosis [11], and inhibit the occurrence of inflammatory response [12].

The foundation for successful tissue construction is the interaction between the microenvironment and the seed cells [13]. However, the monolithic structure of the traditional scaffold limits mass absorption of nutrients and gas molecules such as ions, growth factors, and oxygen. Furthermore, the removal of cell metabolite by-products is a problematic issue, as well as the uneven distribution of cells and the extracellular matrix and necrosis within the structure [14]. Moreover, this “top-to-bottom” strategy is not adequate to flexibly adapt to variations in the shapes of some defects [15][16]. With the development of micro/nano biological manufacturing technology and biomaterials, a new kind of “bottom-up” modular tissue engineering technology was proposed as a way to construct three-dimensional functional tissues by combining micro repetitive functional units to curb those issues [17][18][19]. A simple but effective solution using this “bottom-up” method was put forward in the 1990s that involves introducing microspheres into a continuous matrix instead of compromising the properties of the bulk scaffold [20]. Microspheres are structures with diameters ranging from 1 to 1000 µm, and they can be categorized according to structural differences as solid microspheres, porous microspheres, or hollow microspheres. The solid and the porous types are most commonly used in seed cell culture processes, where the particulates act as bioreactors and exert therapeutic effects by modulating cell behavior [21]. Furthermore, their inherently small size, high drug loading efficiency, infusibility, and high reactivity to the microenvironment enable the hollow microspheres to be effective as a controlled drug delivery tool [22][23].

Microspheres have a number of unique properties compared to large pieces of material materials that make them attractive for biomedical applications. Microspheres can be fabricated from both natural and synthetic materials, and can be made to vary in shape, density, porosity, and size by applying techniques that are often compatible with the encapsulation of biologics. Microspheres for different application scenarios require different properties [24]. Microspheres can be divided into three categories: suspensions, granular and composites. In suspensions, the microspheres reside in a fluid (liquid or air), with minimal interactions between particles. When the particle-packing density increases, granular microspheres form. If microspheres are embedded within a bulky material, a composite is obtained [25]. Physical interactions between microspheres typically result in shear thinning behavior and solid consistency without chemical modification after injection. In addition, microspheres are inherently modular, because multiple microspheres populations can be mixed together to create different materials with different properties [26].

2. Fabrication of Microspheres

2.1. Emulsion Polymerization

Emulsion polymerization is a classic method for preparing microspheres. By utilizing an emulsifier and mechanical agitation, the water-soluble monomers are dispersed in water, thus forming an emulsion. Initiate polymerization is a special method of free radical polymerization [27]. The reaction system consists of a hydrophobic monomer, a water-soluble initiator, an emulsifier, and water. With water as the dispersion medium, the free radical generated by the initiator enters the monomer swelling micelle from the aqueous phase and reacts with the monomer to form a nucleus. The hydrophobic monomer then diffuses from the droplet through the aqueous phase. In the process, the free radical polymerizes with the nucleus generated by the monomer. With the steady growth of the nucleus, it eventually becomes a microsphere and precipitates until the monomer diffusion ends and the droplet disappears. However, inside the microsphere, the monomer continues to polymerize until the reaction ends. Microspheres prepared using this method have high homogeneity and monodispersity, alongside high polymerization speed and molecular weight [28]. The spherical particles are formed mainly because of the interfacial tension; however, in one study, Fab et al. used negatively charged hydrophilic acrylic acid as a comonomer and attempted to introduce the hydrophilic and hydrophobic vinyl monomer into the oil-water interface system. The emulsion interface of the water (hydrophilic monomer aqueous solution) and oil (containing the hydrophobic monomer) was subsequently constructed, and the anisotropic Janus microspheres with hydrophile lipophilic properties were successfully formed by emulsion polymerization. This method can not only synthesize anisotropic Janus microspheres, but also synthesize spherical microspheres with porous structure, offering an entirely new direction for emulsion polymerization [29].

Other types of emulsion polymerization include core shell emulsion polymerization, soap-free emulsion copolymerization, and microemulsion polymerization. Physical methods such as an ultrasonic magnetic field have been proposed, but they are still in the theoretical stage [30].

2.2. Suspension Polymerization

Suspension polymerization refers to the method of free radical polymerization in which the monomer is dissolved with the initiator and suspended in water in the form of droplets, with the water as the continuous phase and monomer as the dispersed phase. Suspension polymerization has a high polymerization rate and requires a high relative molecular mass of the microspheres, whereas the impurity content is far lower than that of emulsion polymerization [31]. Using this method, researchers have successfully synthesized nano monodisperse crosslinked polystyrene microspheres without any chemical derivation or grafting steps. The nano microspheres synthesized using this method have a good shape and no impurities on the surface [32]. In addition to smooth microspheres, porous polymer microspheres have been widely used in the immobilization of enzymes and catalysts, adsorption and separation, detection, and sensing due to their high specific surface area, abundant pores, and good stability. In one case, Zhang et al. successfully prepared surface folded porous polymer microspheres in the traditional suspension polymerization system with the help of phase separation and volume shrinkage [33].

2.3. Precipitation Polymerization

The microspheres obtained via precipitation polymerization not only have narrow particle size distribution and a simple operation process, but they are also easily obtained for follow-up treatments. Unlike other preparation methods, the precipitation polymerization process does not use an additional dispersion stabilizer, so the reaction conditions must be accurately controlled. Additionally, because of the absence of the dispersion stabilizer, and thus the absence of the need to separate it, it is safer for application in the biomedical system [34]. In their study, Yin et al. prepared functional gel microspheres with high adsorption capacity for cationic toxins through the in situ crosslinking polymerization of precipitate droplets. This preparation method is quite simple to achieve. First, a homogeneous aqueous phase reaction solution (monomer, initiator, crosslinking agent, and water) is prepared and then dropped into hot corn oil that has been heated by externally circulating water at 90 °C. Using this method, polymerization is completed in a very short time [35].

One noteworthy type of precipitation polymerization is called dispersion polymerization. Because of its unique polymerization mechanics, dispersion polymerization is widely used in the preparation of various types of polymer microspheres with a size of 0.1–15 μm in diameter [36]. Unlike other methods of precipitation polymerization, stabilizer is needed in the dispersion polymerization system. Precipitation polymerization is the formation of polymers that are insoluble in the mutual poly-sink system [37]. When the length of the oligomer chain generated by the reaction reaches a critical value, the polymer cannot remain dissolved in the reaction medium, allowing polymer microspheres to be obtained. The microspheres are characterized by having a good spherical shape, large particle size (compared with those of emulsion polymerization), narrow particle size distribution, and low viscosity. Precipitation polymerization is commonly used in the preparation of functional microspheres. The dispersion copolymerization reaction system, on the other hand, is very complex, and different comonomers form different polymerization systems, resulting in different reaction behaviors [34].

2.4. Spray Drying Method

Spray drying methods can be categorized as the pressure spray drying method, centrifugal spray drying method, or airflow spray drying method. Sprinklers, desiccators, preheaters, air separation chambers, air filters, collecting bins, and blowers are common components of spray drying. The goal of this method is to disperse the given materials as a mist of tiny droplets, expose them to a hot air flow, and evaporate most of their water, thus obtaining a powder, fine-granular finished product, or semi-finished product [38]. Quinlan et al. encapsulated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in alginate microparticles by spray drying, producing particles less than 10 µm in diameter. Using this process, they achieved effectively encapsulated and controlled VEGF release for 35 days, which was sufficient to increase tubule formation by endothelial cells in vitro [39].

2.5. Microfluidics

Microfluidics is a technology that uses microchannels to manipulate micro fluids. This method integrates one or more functions of a large laboratory on a micro or even nanoscale chip. By effectively and intelligently encapsulating cells or drugs in microspheres, the successful management of their functions and characteristics can be achieved. This process can also result in the development of some unique characteristics, which promote multi-disciplinary exchanges and cooperation, as well as the development of precision medicine, new manufacturing technology, and applied materials. In recent years, the use of microfluidic technology has shown many advantages in the preparation of microspheres. Compared with conventional preparation methods, the microfluidic preparation platform can more accurately control reaction conditions such as temperature and pressure with fast preparation speed and good reproducibility, while also using less raw materials and reagents [40]. More importantly, the size, morphology, and dispersion of particles can be accurately regulated using the microfluidics management preparation platform [41]. The main preparation methods of microspheres by microfluidics at present are the droplet template method and the flow lithography method. The droplet template method refers to the preparation of microdroplets through the introduction of fluid shear, electric field induction, centrifugal throwing, formation of microspheres in the system as a template, and proper curing. Flow lithography is a micro projection technology based on photopolymerization in multiphase laminar flow. It involves irradiating the fluid in the microfluidic chip with an ultraviolet beam in a preset shape, causing the irradiated fluid to partially polymerize according to the beam shape, thus obtaining homogeneous microspheres. The whole preparation process can be completed with the help of a commercial inverted fluorescence microscope [42].

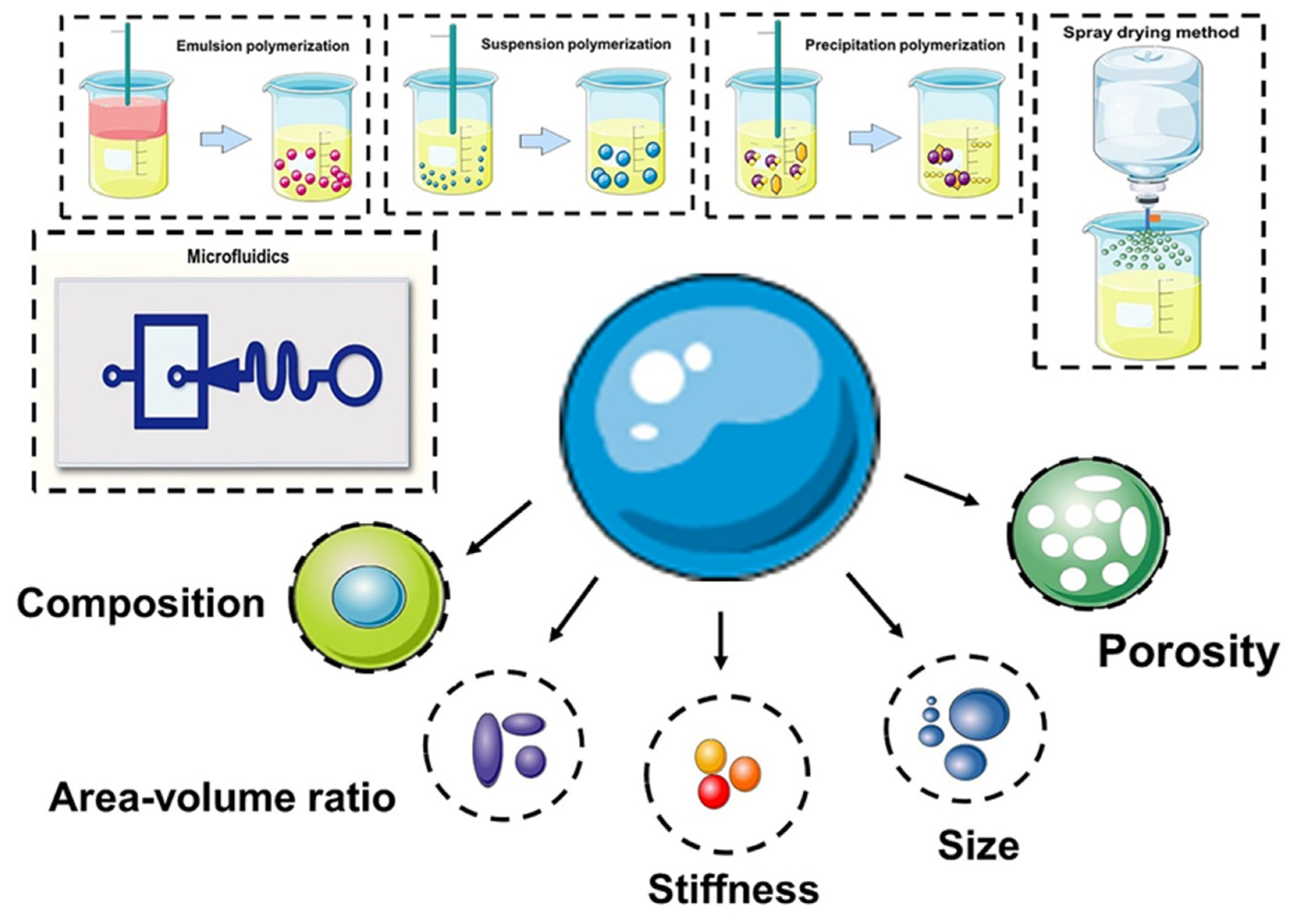

Other studies have used sodium alginate to encapsulate single mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in a microfluidic platform, thus simulating a three-dimensional microenvironment to support cell viability and function, while at the same time protecting cells from environmental stresses. Compared with acellular microgels, the MSCs’ loaded alginate gel microspheres showed significant enhancement in bone formation in a rat tibia ablation model, which lays the foundation for modular bone tissue engineering [43]. In addition to the encapsulation of cells, microfluidics-controlled hydrogel microspheres provide a good supporting environment for cell adhesion and growth. In their study, Cui et al. constructed a bisphosphonate functionalized injectable hydrogel microsphere (GelMA-BP-Mg) using a metal ion ligand coordination reaction to achieve Mg2+ loading and controlled release via magnetics, thereby promoting cancellous bone remodeling in osteoporotic bone defects. The results of the in vivo and in vitro experiments show that the composite microspheres inhibit osteoclasts by stimulating osteoblasts and endothelial cells. This is conducive to osteogenesis and angiogenesis, which effectively promote cancellous bone regeneration [44]. Meanwhile, an efficient transfer platform was designed using new one-step microfluidic technology to achieve the combination of liposomes and photo crosslinked gel matrixes, thus forming monodisperse gel/liposome mixed microgel rapidly under ultraviolet light. Microgel can release kartogenin (KGN) continuously during the degradation period, thus providing a feasible method for the treatment of osteoarthritis in the joint release of KGN [45]. Researchers aim to provide a discussion on the reported particle design methods that can modulate their (bio)chemical/physical and structural characteristics (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Preparation of microspheres and (bio)chemical/physical features as modulating moieties of microspheres.

3. Novel Applications of Microspheres for Bone Tissue Engineering

3.1. 3D Culture of Seed Cells and Construction of Organoid

To ensure the efficient proliferation and differentiation of seed cells in vivo, it is necessary to provide a cell scaffold that acts as an artificial extracellular matrix. The scaffold materials used in bone tissue engineering must have good biocompatibility and surface activity, bone conductivity and bone induction ability, and appropriate pore size and porosity, as well as moderate mechanical strength and plasticity [46]. At present, both biodegradable and non-biodegradable scaffold materials are widely used. However, due to the high levels of mechanical strength and strong biological inertia, non-biodegradable materials can cause secondary surgery problems. This has led to an increase in the study of biodegradable and bioactive materials in recent years [47].

As a microcarrier structure, microspheres have a larger surface area and volume ratio than monolayer cells, so they can effectively promote the growth of cells [48]. Microspheres are commonly used in 3D cell cultures in the process of stem cell growth and differentiation. This is because over the past decade, scientists have found that 3D cell culture technologies can provide cells with a culture environment more akin to the in vivo environment. Thus, the 3D cell culture must be able to simulate the main characteristics of the in vivo environment, including the interactions between cells and the extracellular matrix, between cells and organs, and between cells and other cells, in order to better realize the morphology and function of cells in vitro, understand their physiological function, and establish extensive cell-to-cell and cell-to-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions [49]. At present, studies have confirmed that a 3D culture of stem cells with microspheres can efficiently promote the growth of stem cells as well as osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation [50][51], and promote the paracrine ability of stem cells. This causes more anti-inflammatory factors and nutritional factors (such as VEGF, PDGF and FGF) to be expressed, thus allowing stem cells to play a more effective therapeutic role in bone regeneration [52]. Compared with traditional 2D cultures, the MSCs sphere conditioned medium was more effective in promoting the phenotypic transformation of macrophages from mainly pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2, thereby playing an active anti-inflammatory role [53]. In 3D cultures, human pluripotent stem cells can be cultured to produce a trophoblast-like tissue model, which is helpful in analyzing the potential mechanisms of early human placental development [54]. Additionally, the 3D culture of stem cells includes self-assembly aggregation and encapsulation by hydrogel microspheres. Passanha et al. found that cells encapsulated by alginate hydrogel exhibited better viability on the 14th day, probably because the alginate gel could provide more room for cells and allow for the diffusion of more nutrients and oxygen [55].

The cytoskeleton of the internal structure of the cell provides the basis for the cell’s ability to sense external mechanical rigidity, thus mediating the interactions between the cell and the extracellular environment [56]. Some studies have even suggested that the hypoxic microenvironment may be the leading factor in the enhancement of the therapeutic potential of MSCs in 3D environments [57]. Chen et al. believed that a 3D environment’s conduciveness to the therapeutic effect of stem cells cannot be attributed only to the hypoxic microenvironment. Notably, the slight metabolic conversion of 3D cultured stem cells may have a significant impact on their paracrine potential. Upon further exploration, researchers found that 3D MSCs spheres made by 40,000 cells have the best paracrine and immune regulation ability [58]. Therefore, researchers recommend using microsphere material as a scaffold material to better complete tissue repair.

Organoids are micro-organs with three-dimensional structure grown in vitro using adult stem cells. Their genetic background and histological characteristics are very similar to those of in vivo organs; they have complex structures similar to those of real organs and can partially mimic the physiological functions of the source tissues and organs, which has made them a hot research topic in recent years [59]. A popular cutting-edge technology, stem cell populations propagated through an organoid can replace damaged or diseased tissues for the purpose of treating diseases. It is expected that when this technology reaches a certain stage of development, doctors will use pluripotent stem cells to build organoids that can replace damaged tissues in patients. Scientists can use human-derived stem cells to treat fractures after growing osteogenic-like organs in vitro. A segment of bone unit containing cortical bone, cancellous bone, and a junction interface, injected into the site of a bone defect, can spontaneously assemble and thus heal the fracture [60][61]. Low concentration gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) is a synthetic material that has excellent biocompatibility with cellular structures, and Xie et al. were able to rapidly print uniform GelMA microdroplets measuring approximately 100 μm using an electro-assisted bioprinting method. Due to the low external force applied to separate the droplets, the printing process results in minimal cell damage and can provide an excellent microenvironment for stem cell growth [62]. Alginate, chitosan, cell-laden PEG hydrogel, and other similar natural polymers are compatible with electrohydrodynamic spraying (EHS), and can all be used to generate controlled sized cell-loaded microspheres for potential applications in cell delivery and organoid culture [63]. PDMS microspheres with different elastic modulus (34 kPa, 0.6 MPa, and 2.2 MPa) were prepared and doped into MSCs, thus modulating the mechanical properties of the MSCs growth microenvironment and affecting MSCs differentiation, as MSCs differentiation is tension dependent [64]. It has been shown that MSCs in microspheres exposed to low contractile force are more conducive to adipose tissue differentiation than those exposed to high tension, which are more conducive to osteogenic differentiation [65]. When PDMS microspheres were incorporated into the cell sphere, the interfacial tension was increased due to the decrease in adhesion and the decrease in cadherin [66]. In addition, the introduction of material supports or spacers into the cell sphere increases the cell’s free volume, thus allowing a more frequent exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and waste with the exterior of the cell, thus facilitating cell growth and differentiation [67].

Preparation of cell-laden microspheres by 3D printing is an efficient means to achieve rapid construction of functional large-scale organoids [68]. Current 3D bioprinting technologies for manufacturing different types of organs mostly use droplet-based, extrusion-based, laser-induced forward transfer, and stereolithography bioprinting. Among them, extrusion-based 3D printing is the most popular choice. Hydrogel materials have become the obvious choice for 3D printed microspheres, which provide a highly hydrated environment with excellent biocompatibility. Bulk hydrogels have good shear-thinning properties for extrusion-based bioprinting, whereas granular hydrogels can only achieve this rheological property if they are “jammed” [69]. Jamming means that the particle system changes from a fluid to a solid state. When the particle-to-volume fraction reaches (Φ) to approximately 0.58, the jamming transition can be found. In theory, the monodispersed hard-spherical particles should be maximally jammed in a random configuration at Φ = 0.64 and be perfectly packed at Φ = 0.74. However, packaging of soft hydrogel particles is much more complicated due to inter-particle friction, charge, hardness, and microgel heterogeneity. In addition to this, microscale pores are necessary for cell growth. Therefore, there is currently an unmet need to develop granular jammed hydrogels that can preserve the microscale pores [70]. Ataie and co-workers programmed microgels for reversible interfacial nanoparticle self-assembly, enabling the fabrication of nanoengineered granular bioinks with well-preserved microporosity, enhanced printability, and shape fidelity [71]. Four-dimensional printing is a rapidly emerging field that has been developed from 3D printing, where printed structures change in shape, properties, or function when exposed to predetermined stimuli, such as humidity and temperature photoelectric stimuli. Four-dimensional bioprinting is a promising method to build cell-laden constructs that have complex geometries and functions for tissue/organ regeneration applications. A single-component jammed micro-flake hydrogel has been developed for 4D bioprinting with shear-thinning, shear-yielding, and rapid self-healing properties. As such, it can be printed smoothly as a stable three-dimensional biological structure when a photoinitiator and a UV absorber are added, and a gradient in cross-linking density is formed. After performing shape deformation, the hydrogel produced well-defined configurations and high cell viability, which may provide a number of applications in bone tissue engineering [72].

3.2. Endochondral Ossification for the Reparation of Large Bone Defects

Endochondral ossification has become an effective strategy in the repair of large segmental bone defects. The process of endochondral ossification occurs through the formation of a calcified cartilage matrix containing hypertrophic chondrocytes. MSCs undergo cartilage template formation, blood vessel formation, and mineralization. This avascular cartilage template secretes angiogenic factors that induce vascular growth in the defect site, a process that also activates osteogenic signaling pathways and ultimately promotes their restructuring into bone [73]. Mikael et al. combined gel phase with load-bearing and porous biodegradable matrices to produce hybrid matrices, with the PLGA polymer matrix providing mechanical stability, while the (hyaluronic acid-fibrin) gel-phase was expected to support the seeded MSC chondrogenesis, hypertrophy, and bone formation [74]. Endochondral ossification was achieved by incorporating gelatin particles capable of relatively rapid release of TGF-β1 and mineral-coated hydroxyapatite particles, allowing a more sustained release of BMP-2 into MSCs aggregates, in order to take advantage of the sequential release of dual growth factors. This method did not need long-term in vitro chondrogenic priming, and it exhibited greater mineralization than pure cell aggregates treated with exogenous growth factors [75]. Lin et al. applied the mechanism of endochondral ossification and co-cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells with MSCs to create pre-vascularized bone-like tissue, which exhibited greater potential than either of the two cells cultured separately.

Xie et al. constructed a 3D culture system based on hydrogel microspheres using digital light-processing, which shows excellent in vitro stepwise-induction of BMSCs and achieves a state of simultaneous proliferation and differentiation of stem cells at the transcriptional level, as well as closely mimics the osteogenesis process. It also closely mimics the composition and behavior of stem progenitor cells in cartilage involved in osteogenesis. After in situ implantation, rapid bone repair was achieved within 4 weeks by advancing the regenerative process of endochondral osteogenesis, which indicates that in vitro construction of osteo-callus-like organs (osteo-callus organoids) according to developmental or regenerative processes is an effective strategy to promote rapid regeneration of bone tissue and the healing of bone defects [76]. Ji et al. developed a “building block” controlled drug delivery system with macrophage modulating and injectable properties consisting of porous chitosan (CS) microspheres and hydroxypropyl chitosan (HPCH) temperature-sensitive hydrogels, in which dimethoxyglycine (DMOG) was loaded into temperature-sensitive HPCH hydrogels and KGN was grafted onto porous CS microspheres, thus forming the HPCH hydrogels/CS microspheres composite scaffold, which can effectively regulate the regenerative microenvironment at the defect site, recruit autologous stem cells, and provide abundant cell adhesion sites, thus achieving M2 polarization of local macrophages and promoting osteochondral regeneration [77]. Janus particles are structures that integrate two or more composites with different chemical compositions into a single structural system. Janus particles can integrate different functional properties and perform multiple synergistic functions simultaneously because of their asymmetric composition and structure [78]. The application of Janus particles allows for the controlled release of drugs, and therefore it has promising applications in bone tissue engineering based on endochondral ossification.

3.3. Construction of Microspheres Integrating Multiple Functions

The generation of microspheres in bone tissue engineering is a fast-growing field, renowned for its therapeutic effects in regenerative medicine, particularly in the regeneration and replacement of bones. However, these microsphere structures are not limited to tissue regeneration, and have been found to have additional functions in recent years [79]. The “clean-to-repair” rhythm in the dynamic pathological osteoimmune microenvironment is essential to bone healing but is often disturbed by intense inflammation. Extracellular bioactive cations (Mg2+) were doped into (PLGA)/MgO-alendronate microspheres, and the microspheres effectively regulated the microenvironment by inducing the polarization of macrophages from the M0 to the M2 phenotype and enhancing the production of anti-inflammatory (IL-10) and osteopathic (BMP-2 and TGF-β1) cytokines. This has been proven to promote proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and produce a good bone regenerating effect [80][81]. Liang et al. combined microfluidic microspheres and self-assembled collagen nanofibers to form an injectable porous microsphere with a hierarchical micro/nanostructure that mimics the extracellular matrix and activates integrin-mediated macrophage (Mφ) polarization, resulting in microenvironmental reprogramming for paracrine transformation [82]. The microenvironment of bone defects resulting from some diseases produces large amounts of ROS, which not only impairs the regenerative potential of endemic stem cells but also reduces the therapeutic efficacy of stem cells implanted in the defect area. Excess ROS or insufficient antioxidants can make these bone defects difficult to repair. Therefore, for the treatment of refractory bone healing, there is an urgent need for new strategies to fabricate antioxidant microspheres that function as stem cell carriers to promote bone regeneration in the ROS microenvironment [83]. Yang et al. constructed fullerol-hydrogel microfluidic spheres by using a one-step innovative microfluidic technique for in situ regulation of redox homeostasis in stem cells and promotion of refractory bone healing [84]. Zheng et al. produced bone targeting antioxidative nano-iron oxide for treating postmenopausal osteoporosis [85]. Strategies now available for ROS scavenging to regulate the microenvironment include inorganic nanoparticles (cerium oxide nanoparticles, iron oxide nanoparticles, manganese nanoparticles, and carbon nanomaterials) and organic moieties (phenol group, sulfur, and boronic acid) [86].

The incorporation of antibiotics and some active ingredients from plants, such as cinnamaldehyde and nanosilver, into microspheres gives the microspheres antibacterial effects, thus making them a viable treatment for osteomyelitis bone defects [87][88][89][90]. Meanwhile, the incorporation of the antitumor drug adriamycin into microspheres for bone tissue engineering can achieve long-term release, resulting in bone regeneration and the destruction of tumor cells, and thus shows good prospects for application [91]. The doping of M-type ferrite particles (SrFe12O19) into the microspheres enables the rapid release of doxorubicin (DOX) under the irradiation of near-infrared laser light, enabling the promotion of osteogenesis and enhancing synergistic photothermal chemotherapy against osteosarcoma [92]. Bleeding due to bone defects is a clinically recognized category of refractory bleeding, wherein damage to the abundant blood vessels in cancellous bone leads to continuous bleeding (oozing) during the slow bone repair process. Therefore, Liu et al. devised a method to construct multilayer structured microspheres based on branched-chain starch, porous starch, and tannic acid of biomass (maize and grape) origin and MQ2T2 with the outmost polyphenol layer having unique platelet adhesion, activation, and erythrocyte aggregation properties. The microspheres had excellent hemostatic and pro-bone repair properties with good therapeutic effects in both rat and beagle models of cancellous bone defects. They also had excellent hemostatic and pro-bone repair properties [93].

References

- Wang, W.; Yeung, K.W.K. Bone grafts and biomaterials substitutes for bone defect repair: A review. Bioact. Mater. 2017, 2, 224–247.

- Schwartz, C.E.; Martha, J.F.; Kowalski, P.; Wang, D.A.; Bode, R.; Li, L.; Kim, D.H. Prospective evaluation of chronic pain associated with posterior autologous iliac crest bone graft harvest and its effect on postoperative outcome. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2009, 7, 49.

- Langer, R.; Vacanti, J.P. Tissue engineering. Science 1993, 260, 920–926.

- Turnbull, G.; Clarke, J.; Picard, F.; Riches, P.; Jia, L.; Han, F.; Li, B.; Shu, W. 3D bioactive composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2018, 3, 278–314.

- Chapekar, M.S. Tissue engineering: Challenges and opportunities. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 53, 617–620.

- Guo, L.; Liang, Z.; Yang, L.; Du, W.; Yu, T.; Tang, H.; Li, C.; Qiu, H. The role of natural polymers in bone tissue engineering. J. Control. Release 2021, 338, 571–582.

- Xu, H.; Wang, P.; Wang, L.; Bao, C.; Chen, Q.; Weir, M.D.; Chow, L.C.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, X.; Reynolds, M.A. Calcium phosphate cements for bone engineering and their biological properties. Bone Res. 2017, 5, 17056.

- Ding, D.; Shyu, W.C.; Lin, S.Z. Mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2011, 20, 5–14.

- Via, A.G.; Frizziero, A.; Oliva, F. Biological properties of mesenchymal Stem Cells from different sources. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012, 2, 154–162.

- Lei, T.; Deng, S.; Chen, P.; Xiao, Z.; Cai, S.; Hang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; Du, H. Metformin enhances the osteogenesis and angiogenesis of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for tissue regeneration engineering. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2021, 141, 106086.

- Hu, Y.; Tao, R.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Lin, Z.; Panayi, A.C.; Xue, H.; Li, H.; Xiong, L.; Liu, G. Exosomes Derived from Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cells Alleviate Compression-Induced Nucleus Pulposus Cell Apoptosis by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 2310025.

- Xu, Z.; Tian, N.; Li, S.; Li, K.; Guo, H.; Zhang, H.; Jin, H.; An, M.; Yu, X. Extracellular vesicles secreted from mesenchymal stem cells exert anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects via transmitting microRNA-18b in rats with diabetic retinopathy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 101 Pt B, 108234.

- Dixon, D.T.; Gomillion, C.T. Conductive Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering: Current State and Future Outlook. J. Funct. Biomater. 2021, 13, 1.

- Howard, D.; Buttery, L.D.; Shakesheff, K.M.; Roberts, S.J. Tissue engineering: Strategies, stem cells and scaffolds. J. Anat. 2008, 213, 66–72.

- Thevenot, P.; Nair, A.; Dey, J.; Yang, J.; Tang, L. Method to analyze three-dimensional cell distribution and infiltration in degradable scaffolds. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2008, 14, 319–331.

- Tuli, R.; Li, W.J.; Tuan, R.S. Current state of cartilage tissue engineering. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2003, 5, 235–238.

- Khademhosseini, A.; Langer, R. Microengineered hydrogels for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 5087–5092.

- Leferink, A.; Schipper, D.; Arts, E.; Vrij, E.; Rivron, N.; Karperien, M.; Mittmann, K.; van Blitterswijk, C.; Moroni, L.; Truckenmüller, R. Engineered micro-objects as scaffolding elements in cellular building blocks for bottom-up tissue engineering approaches. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 2592–2599.

- Griffin, D.R.; Weaver, W.M.; Scumpia, P.O.; Di Carlo, D.; Segura, T. Accelerated wound healing by injectable microporous gel scaffolds assembled from annealed building blocks. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 737–744.

- Turgeman, G.; Pittman, D.D.; Müller, R.; Kurkalli, B.G.; Zhou, S.; Pelled, G.; Peyser, A.; Zilberman, Y.; Moutsatsos, I.K.; Gazit, D. Engineered human mesenchymal stem cells: A novel platform for skeletal cell mediated gene therapy. J. Gene Med. 2001, 3, 240–251.

- Park, J.H.; Pérez, R.A.; Jin, G.Z.; Choi, S.J.; Kim, H.W.; Wall, I.B. Microcarriers designed for cell culture and tissue engineering of bone. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2013, 19, 172–190.

- Biondi, M.; Ungaro, F.; Quaglia, F.; Netti, P.A. Controlled drug delivery in tissue engineering. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 229–242.

- Mouriño, V.; Boccaccini, A.R. Bone tissue engineering therapeutics: Controlled drug delivery in three-dimensional scaffolds. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, 209–227.

- Tavassoli, H.; Alhosseini, S.N.; Tay, A.; Chan, P.P.Y.; Oh, S.K.W.; Warkiani, M.E. Large-scale production of stem cells utilizing microcarriers: A biomaterials engineering perspective from academic research to commercialized products. Biomaterials 2018, 181, 333–346.

- Daly, A.C.; Riley, L.; Segura, T.; Burdick, J.A. Hydrogel microparticles for biomedical applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 20–43.

- Mealy, J.E.; Chung, J.J.; Jeong, H.H.; Issadore, D.; Lee, D.; Atluri, P.; Burdick, J.A. Injectable Granular Hydrogels with Multifunctional Properties for Biomedical Applications. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1705912.

- Dupont, H.; Héroguez, V.; Schmitt, V. Elaboration of capsules from Pickering double emulsion polymerization stabilized solely by cellulose nanocrystals. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 279, 118997.

- Honciuc, A.; Negru, O.I. Role of Surface Energy of Nanoparticle Stabilizers in the Synthesis of Microspheres via Pickering Emulsion Polymerization. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 995.

- Fan, J.B.; Song, Y.; Liu, H.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Liu, H.; Meng, J.; Gu, L.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L. A general strategy to synthesize chemically and topologically anisotropic Janus particles. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1603203.

- Yin, G.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, H.; Du, Q.; Zhang, H. Preparation of graphene oxide coated polystyrene microspheres by Pickering emulsion polymerization. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 394, 192–198.

- McClements, D.J. Designing biopolymer microgels to encapsulate, protect and deliver bioactive components: Physicochemical aspects. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 240, 31–59.

- Zhang, N.; Dong, J.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Ou, J.; Ye, M. One-step synthesis of hydrophilic microspheres for highly selective enrichment of N-linked glycopeptides. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1130, 91–99.

- Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Xu, J.; Ahmad, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, Q.; Kou, X.; Zhang, B. Surface Microstructure Regulation of Porous Polymer Microspheres by Volume Contraction of Phase Separation Process in Traditional Suspension Polymerization System. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2019, 40, e1800768.

- Hua, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, N.; Wang, Z.; Gao, X.; Gao, J.; Zheng, A. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microsphere production based on quality by design: A review. Drug Deliv. 2021, 28, 1342–1355.

- Yin, J.; Sun, W.; Song, X.; Ji, H.; Yang, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, C. Precipitated droplets in-situ cross-linking polymerization towards hydrogel beads for ultrahigh removal of positively charged toxins. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 238, 116497.

- Zetterlund, P.B.; Thickett, S.C.; Perrier, S.; Bourgeat-Lami, E.; Lansalot, M. Controlled/Living Radical Polymerization in Dispersed Systems: An Update. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9745–9800.

- Liu, X.; Debije, M.G.; Heuts, J.P.; Schenning, A. Liquid-Crystalline Polymer Particles Prepared by Classical Polymerization Techniques. Chemistry 2021, 27, 14168–14178.

- Mendonsa, N.; Almutairy, B.; Kallakunta, V.R.; Sarabu, S.; Thipsay, P.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M.A. Manufacturing strategies to develop amorphous solid dispersions: An overview. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 101459.

- Quinlan, E.; López-Noriega, A.; Thompson, E.M.; Hibbitts, A.; Cryan, S.A.; O’Brien, F.J. Controlled release of vascular endothelial growth factor from spray-dried alginate microparticles in collagen-hydroxyapatite scaffolds for promoting vascularization and bone repair. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2017, 11, 1097–1109.

- Shakeri, A.; Khan, S.; Didar, T.F. Conventional and emerging strategies for the fabrication and functionalization of PDMS-based microfluidic devices. Lab Chip 2021, 21, 3053–3075.

- Liu, T.; Weng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Yang, H. Applications of Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) Hydrogels in Microfluidic Technique-Assisted Tissue Engineering. Molecules 2020, 25, 5305.

- Sun, X.T.; Liu, M.; Xu, Z.R. Microfluidic fabrication of multifunctional particles and their analytical applications. Talanta 2014, 121, 163–177.

- An, C.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, B.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Liao, H.; Ren, C.; et al. Continuous microfluidic encapsulation of single mesenchymal stem cells using alginate microgels as injectable fillers for bone regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2020, 111, 181–196.

- Zhao, Z.; Li, G.; Ruan, H.; Chen, K.; Cai, Z.; Lu, G.; Li, R.; Deng, L.; Cai, M.; Cui, W. Capturing Magnesium Ions via Microfluidic Hydrogel Microspheres for Promoting Cancellous Bone Regeneration. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 13041–13054.

- Yang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, F.; Deng, L.; Xu, X.; Cui, W. Microfluidic liposomes-anchored microgels as extended delivery platform for treatment of osteoarthritis. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 400, 126004.

- Yu, P.; Yu, F.; Xiang, J.; Zhou, K.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Z.; Rong, X.; Ding, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, W.; et al. Mechanistically Scoping Cell-free and Cell-dependent Artificial Scaffolds in Rebuilding Skeletal and Dental Hard Tissues. Adv. Mater. 2021, 34, 2107922.

- Cao, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, M.; Liu, Y.; Cui, X.; Liang, J.; Wang, Q.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X. Childhood Cartilage ECM Enhances the Chondrogenesis of Endogenous Cells and Subchondral Bone Repair of the Unidirectional Collagen-dECM Scaffolds in Combination with Microfracture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 57043–57057.

- Chen, X.Y.; Chen, J.Y.; Tong, X.M.; Mei, J.G.; Chen, Y.F.; Mou, X.Z. Recent advances in the use of microcarriers for cell cultures and their ex vivo and in vivo applications. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 42, 1–10.

- Indana, D.; Agarwal, P.; Bhutani, N.; Chaudhuri, O. Viscoelasticity and Adhesion Signaling in Biomaterials Control Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Morphogenesis in 3D Culture. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2101966.

- Le, H.T.-N.; Vu, N.B.; Nguyen, P.D.-N.; Dao, T.T.-T.; To, X.H.-V.; Van Pham, P. In vitro cartilage differentiation of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell spheroids cultured in porous scaffolds. Front. Biosci. 2021, 26, 266–285.

- Shanbhag, S.; Suliman, S.; Mohamed-Ahmed, S.; Kampleitner, C.; Hassan, M.N.; Heimel, P.; Dobsak, T.; Tangl, S.; Bolstad, A.I.; Mustafa, K. Bone regeneration in rat calvarial defects using dissociated or spheroid mesenchymal stromal cells in scaffold-hydrogel constructs. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 575.

- Deng, J.; Li, M.; Meng, F.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Tang, P. 3D spheroids of human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuate spinal cord injury in mice. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1096.

- Ylöstalo, J.H.; Bartosh, T.J.; Coble, K.; Prockop, D.J. Human mesenchymal stem/stromal cells cultured as spheroids are self-activated to produce prostaglandin E2 that directs stimulated macrophages into an anti-inflammatory phenotype. Stem Cells 2012, 30, 2283–2296.

- Cui, K.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, H.; Guo, Y.; Deng, P.; Liu, H.; Shao, X.; Qin, J. Establishment of Trophoblast-Like Tissue Model from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells in Three-Dimensional Culture System. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2100031.

- Passanha, F.R.; Gomes, D.B.; Piotrowska, J.; Moroni, L.; Baker, M.B.; LaPointe, V.L.S. A comparative study of mesenchymal stem cells cultured as cell-only aggregates and in encapsulated hydrogels. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2022, 16, 14–25.

- Barooji, Y.F.; Hvid, K.G.; Petitjean, I.I.; Brickman, J.M.; Oddershede, L.B.; Bendix, P.M. Changes in Cell Morphology and Actin Organization in Embryonic Stem Cells Cultured under Different Conditions. Cells 2021, 10, 2859.

- Schmitz, C.; Potekhina, E.; Belousov, V.V.; Lavrentieva, A. Hypoxia Onset in Mesenchymal Stem Cell Spheroids: Monitoring with Hypoxia Reporter Cells. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 611837.

- Chen, L.C.; Wang, H.W.; Huang, C.C. Modulation of Inherent Niches in 3D Multicellular MSC Spheroids Reconfigures Metabolism and Enhances Therapeutic Potential. Cells 2021, 10, 2747.

- Hu, W.; Lazar, M. Modelling metabolic diseases and drug response using stem cells and organoids. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 744–759.

- Park, Y.; Cheong, E.; Kwak, J.; Carpenter, R.; Shim, J.; Lee, J. Trabecular bone organoid model for studying the regulation of localized bone remodeling. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd6495.

- Mielan, B.; Sousa, D.M.; Krok-Borkowicz, M.; Eloy, P.; Dupont, C.; Lamghari, M.; Pamuła, E. Polymeric Microspheres/Cells/Extracellular Matrix Constructs Produced by Auto-Assembly for Bone Modular Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7897.

- Xie, M.; Gao, Q.; Zhao, H.; Nie, J.; Fu, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Shao, L.; Fu, J.; Chen, Z.; et al. Electro-Assisted Bioprinting of Low-Concentration GelMA Microdroplets. Small 2019, 15, e1804216.

- Qayyum, A.S.; Jain, E.; Kolar, G.; Kim, Y.; Sell, S.A.; Zustiak, S.P. Design of electrohydrodynamic sprayed polyethylene glycol hydrogel microspheres for cell encapsulation. Biofabrication 2017, 9, 025019.

- Abbasi, F.; Ghanian, M.H.; Baharvand, H.; Vahidi, B.; Eslaminejad, M.B. Engineering mesenchymal stem cell spheroids by incorporation of mechanoregulator microparticles. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 84, 74–87.

- Sart, S.; Tsai, A.C.; Li, Y.; Ma, T. Three-dimensional aggregates of mesenchymal stem cells: Cellular mechanisms, biological properties, and applications. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2014, 20, 365–380.

- Turlier, H.; Maître, J.L. Mechanics of tissue compaction. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 47–48, 110–117.

- Hayashi, S.; Sasaki, Y.; Kubo, H.; Sawada, S.I.; Kinoshita, N.; Marukawa, E.; Harada, H.; Akiyoshi, K. Construction of Hybrid Cell Spheroids Using Cell-Sized Cross-Linked Nanogel Microspheres as an Artificial Extracellular Matrix. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater. 2021, 4, 7848–7855.

- Daly, A.C.; Davidson, M.D.; Burdick, J.A. 3D bioprinting of high cell-density heterogeneous tissue models through spheroid fusion within self-healing hydrogels. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 753.

- Cheng, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Yu, Z.Y. Granular hydrogels for 3D bioprinting applications. View 2020, 1, 20200060.

- Riley, L.; Schirmer, L.; Segura, T. Granular hydrogels: Emergent properties of jammed hydrogel microparticles and their applications in tissue repair and regeneration. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 60, 1–8.

- Ataie, Z.; Kheirabadi, S.; Zhang, J.W.; Kedzierski, A.; Petrosky, C.; Jiang, R.; Vollberg, C.; Sheikhi, A. Nanoengineered Granular Hydrogel Bioinks with Preserved Interconnected Microporosity for Extrusion Bioprinting. Small 2022, 18, e2202390.

- Ding, A.; Jeon, O.; Cleveland, D.; Gasvoda, K.L.; Wells, D.; Lee, S.J.; Alsberg, E. Jammed Micro-Flake Hydrogel for Four-Dimensional Living Cell Bioprinting. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2109394.

- Mackie, E.J.; Ahmed, Y.A.; Tatarczuch, L.; Chen, K.S.; Mirams, M. Endochondral ossification: How cartilage is converted into bone in the developing skeleton. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 46–62.

- Mikael, P.E.; Golebiowska, A.A.; Xin, X.; Rowe, D.W.; Nukavarapu, S.P. Evaluation of an Engineered Hybrid Matrix for Bone Regeneration via Endochondral Ossification. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 48, 992–1005.

- Dang, P.N.; Dwivedi, N.; Phillips, L.M.; Yu, X.; Herberg, S.; Bowerman, C.; Solorio, L.D.; Murphy, W.L.; Alsberg, E. Controlled Dual Growth Factor Delivery From Microparticles Incorporated within Human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Aggregates for Enhanced Bone Tissue Engineering via Endochondral Ossification. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2016, 5, 206–217.

- Xie, C.; Liang, R.; Ye, J.; Peng, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhu, Q.; Shen, X.; Hong, Y.; Wu, H.; Sun, W.; et al. High-efficient engineering of osteo-callus organoids for rapid bone regeneration within one month. Biomaterials 2022, 288, 121741.

- Ji, X.; Shao, H.; Li, X.; Ullah, M.W.; Luo, G.; Xu, Z.; Ma, L.; He, X.; Lei, Z.; Li, Q.; et al. Injectable immunomodulation-based porous chitosan microspheres/HPCH hydrogel composites as a controlled drug delivery system for osteochondral regeneration. Biomaterials 2022, 285, 121530.

- Feng, Z.Y.; Liu, T.T.; Sang, Z.T.; Lin, Z.S.; Su, X.; Sun, X.T.; Yang, H.Z.; Wang, T.; Guo, S. Microfluidic Preparation of Janus Microparticles With Temperature and pH Triggered Degradation Properties. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 756758.

- Neto, M.D.; Oliveira, M.B.; Mano, J.F. Microparticles in Contact with Cells: From Carriers to Multifunctional Tissue Modulators. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1011–1028.

- Lin, Z.; Shen, D.; Zhou, W.; Zheng, Y.; Kong, T.; Liu, X.; Wu, S.; Chu, P.K.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, J.; et al. Regulation of extracellular bioactive cations in bone tissue microenvironment induces favorable osteoimmune conditions to accelerate in situ bone regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 2315–2330.

- Tan, S.; Wang, Y.; Du, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, S. Injectable bone cement with magnesium-containing microspheres enhances osteogenesis via anti-inflammatory immunoregulation. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 3411–3423.

- Wu, L.; Xu, Y.; Xi, K.; Gu, Y.; Tang, J.; Xin, T.; Yang, H.; Wang, L.; Cui, W.; Chen, L. Regulation of macrophage subtype via injectable micro/nano-structured porous microsphere for reprogramming osteoimmune microenvironment. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 439, 135692.

- Li, Q.; Gao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Guan, M.X. The role of mitochondria in osteogenic, adipogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Protein Cell 2017, 8, 439–445.

- Yang, J.; Liang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, M.; Deng, L.; Cui, W.; Xu, X. Fullerol-hydrogel microfluidic spheres for in situ redox regulation of stem cell fate and refractory bone healing. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 4801–4815.

- Zheng, L.; Zhuang, Z.; Li, Y.; Shi, T.; Fu, K.; Yan, W.; Zhang, L.; Wang, P.; Li, L.; Jiang, Q. Bone targeting antioxidative nano-iron oxide for treating postmenopausal osteoporosis. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 14, 250–261.

- Kim, Y.E.; Kim, J. ROS-Scavenging Therapeutic Hydrogels for Modulation of the Inflammatory Response. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 14, 23002–23021.

- Chotchindakun, K.; Pekkoh, J.; Ruangsuriya, J.; Zheng, K.; Unalan, I.; Boccaccini, A.R. Fabrication and Characterization of Cinnamaldehyde-Loaded Mesoporous Bioactive Glass Nanoparticles/PHBV-Based Microspheres for Preventing Bacterial Infection and Promoting Bone Tissue Regeneration. Polymers 2021, 13, 1794.

- Wei, P.; Yuan, Z.; Cai, Q.; Mao, J.; Yang, X. Bioresorbable Microspheres with Surface-Loaded Nanosilver and Apatite as Dual-Functional Injectable Cell Carriers for Bone Regeneration. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2018, 39, e1800062.

- Huang, Y.; Du, Z.; Zheng, T.; Jing, W.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Mao, J.; Zhang, X.; Cai, Q.; Chen, D.; et al. Antibacterial, conductive, and osteocompatible polyorganophosphazene microscaffolds for the repair of infectious calvarial defect. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2021, 109, 2580–2596.

- Meng, D.; Francis, L.; Thompson, I.D.; Mierke, C.; Huebner, H.; Amtmann, A.; Roy, I.; Boccaccini, A.R. Tetracycline-encapsulated P(3HB) microsphere-coated 45S5 Bioglass(®)-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2013, 24, 2809–2817.

- Farzin, A.; Etesami, S.A.; Goodarzi, A.; Ai, J. A facile way for development of three-dimensional localized drug delivery system for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 105, 110032.

- Yang, F.; Lu, J.; Ke, Q.; Peng, X.; Guo, Y.; Xie, X. Magnetic Mesoporous Calcium Sillicate/Chitosan Porous Scaffolds for Enhanced Bone Regeneration and Photothermal-Chemotherapy of Osteosarcoma. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7345.

- Liu, J.Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, D.; Ding, X.; Shen, C.; Xu, F.J. Biomass-Derived Multilayer-Structured Microparticles for Accelerated Hemostasis and Bone Repair. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2002243.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cell & Tissue Engineering

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.0K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

09 Feb 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No