| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ferenc Sipos | -- | 3102 | 2023-01-19 06:53:52 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | + 10 word(s) | 3112 | 2023-01-20 02:46:27 | | |

Video Upload Options

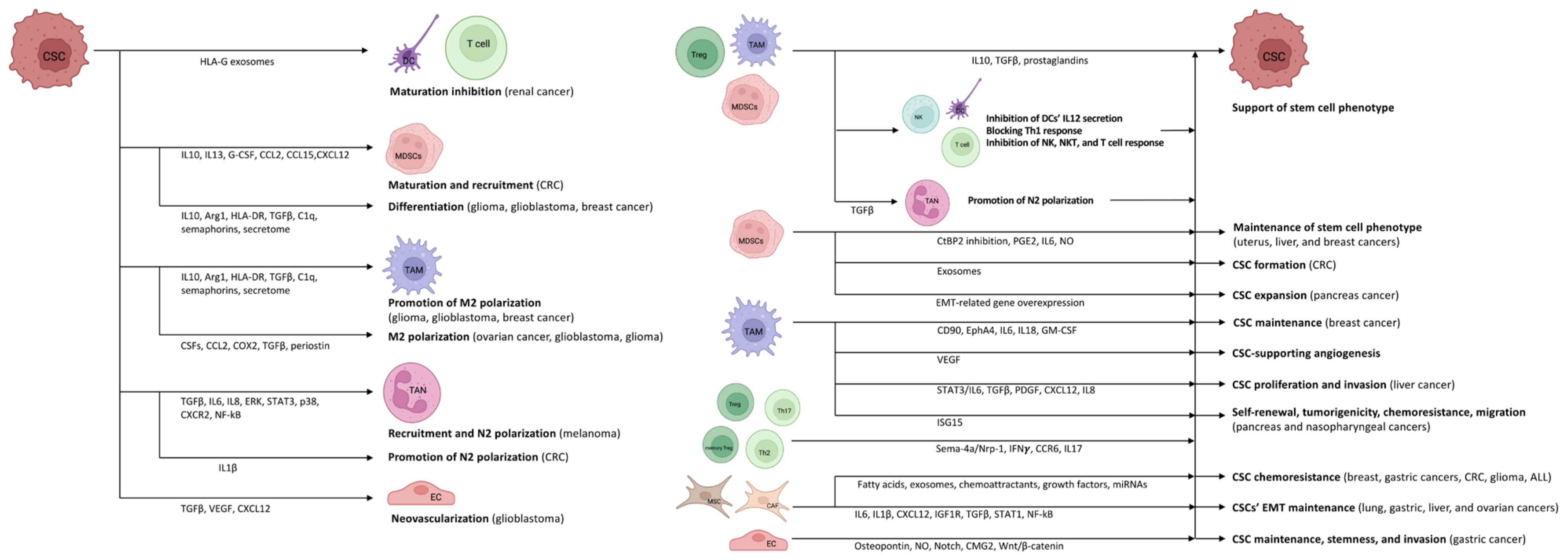

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are capable of altering their own properties in a variety of ways to preserve their stem cell phenotype, resist different therapies, and evade the immune system’s anti-tumor attack. Through immune escape mechanisms, they are not only able to hide themselves from the immune system but also to influence the anti-tumor immune elimination mechanisms in a way that is favorable to them. By manipulating their own capabilities, CSCs have the potential to develop entirely novel anti-cancer treatments and methods to prevent disease recurrence. It is clear that there is an intense and complex multi-level relationship between the tumor microenvironment (TME) and CSCs. CSCs are able to develop an inflammatory niche that allows them to persist and divide on their own. They maintain an intense relationship with the cellular elements of the TME, reprogramming them into cells for the survival and proliferation of CSCs. In turn, the reprogrammed TME cells enhance the survival and proliferation of CSCs and thereby facilitate their own survival and function.

1. Cancer stem cells Influence Their Own Capabilities by Different Mechanisms

2. The Mutual Role of TME and CSCs in Immunomodulation and Stem Cell Niche Maintenance

The heterogeneous (i.e., differences in immune cell infiltration and the amount of necrotic tumor cells, interstitial pressure, genetic and epigenetic alterations) and location dependent (i.e., tumor periphery vs. tumor core) tumor microenvironment (TME) is consisting of stroma, extracellular matrix, vasculature, immune cells, and different signaling molecules and pathways (i.e., Notch-, Wnt-, and Hedgehog-pathways) [16][17]. Crosstalk between CSCs and cells in the TME is variable and extensive, involving interconnections between CSCs, tumor stromal cells, and non-CSCs. It is assumed that CSCs inhabit a particular sub-compartment of TME known as the CSC niche. A favorable microenvironment and the absence of specific stimuli that affect cell proliferation keep CSCs quiescent [18]. CSCs survive tumor eradication in quiescence but do not lose their malignant potential, orchestrating the transition to the escape phase. According to acute leukemia studies, repeated tumor growth is triggered by the aggressive and slowly dividing CSC clone [19]. During the escape phase, CSCs secrete cytokines, chemokines, and soluble factors to blunt and alter immune functions and develop immune tolerance in order to create a pro-tumor niche [20]. Tregs, TAMs, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are the main organizers of this process, as they mainly enhance the formation of an immune-tolerant TME by secreting interleukin (IL)10, TGFβ, and prostaglandins, as found in colorectal cancer (CRC) [21][22][23][24]. They also inhibit the secretion of IL12 by DCs, block the efficient Th1 response, and inhibit NK, natural killer T (NKT), and effector T cells [22][23][24][25]. During the further development of TME, the formation of angiogenesis-promoting N2-polarized tumor-associated neutrophil granulocytes (TANs) is enhanced through immunosuppressive factors and cytokines (e.g., TGFβ) [26].

In cancer patients, a so-called emergency myelopoiesis is observed, whereby TAMs and MDSCs proliferate in abundance, leading to an abnormal overgrowth of tumor-supporting myeloid cells [27][28]. In addition to the local immune cell dysregulation that occurs in TME, cancers also alter the differentiation of bone marrow progenitors through systemic effects, thereby affecting the extent, composition, and specific functions of hemopoiesis [29][30]. Myeloid cells that have been transferred from the bone marrow to the periphery are transported to the tumor, where they encounter extreme conditions (e.g., hypoxia, low pH, low glucose, and inflammatory signals). The altered microenvironment further enhances their reprogramming towards a pro-tumor phenotype [25][31]. CSCs promote the differentiation of immature myeloid cells by secreting inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL10, IL13) [32]. In addition, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)2, CCL15, and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL)12 produced by CSCs recruit additional MDSCs to the TME in colon cancers [33][34]. Experimental results in pancreatic cancer have demonstrated that monocyte-derived MDSCs (M-MDSCs) promote CSC expansion and the expression of genes related to the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [35]. Similarly, in CRC, granulocyte-derived MDSCs (G-MDSCs) promote CSC formation via exosomes, especially within hypoxic microenvironments [36].

Tregs are also an important component of the TME. Tregs are essentially immunosuppressive and act against tissue damage caused by inflammation [37]. In tumors, however, Tregs suppress the anti-tumor effect of tumor-infiltrating immune cells, thereby promoting tumor escape. The functions of Tregs and their polarization between “anti-tumor” and “pro-tumor” states are regulated by complex molecular and cellular interactions. The binding of semaphorin-4a (Sema-4a) expressed on immune cells to neuropilin-1 (Nrp-1), a receptor for Tregs, enhances the survival and immunosuppressive activity of Tregs. The Nrp-1/Sema-4a pathway is absolutely required for the protection and prolongation of Treg survival in TME [37][38]. Other T cell types can interconvert between phenotypes as well. IL17 producing CD4+ Th17 and Th2 cell are able to switch to IFNγ producing ones via epigenetic, metabolic, and cytokine signaling pathways [39].

3. The CSC-TME Crosstalk in Highly Inflammatory Cancers

The link between inflammation and the development of cancer is rather complex [76]. In the case of acute inflammation following tumor antigen uptake or activation by a Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonist, mature DCs may regulate the anti-tumor immune response by modulating the inflammatory response through various mechanisms (e.g., cross-presentation of tumor antigens and priming of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells, polarization of immune cells towards the anti-tumor phenotype, recruitment of NK cells, thereby maintaining the T cell response) [76][77]. If the acute inflammation is not resolved, it is prolonged over time and transforms into chronic inflammation. In this microenvironment, cancer cells (including CSCs) can hijack DCs, thereby preventing the presentation of tumor antigens, and in addition, they can recruit a variety of immunosuppressive cells (e.g., MDSCs, Tregs, M2-TAMs, and N2-TANs) by producing cytokines, chemokines, and inflammatory mediators. The resulting environment is rich in pro-angiogenic and pro-tumorigenic factors and prevents innate immunity and the T cell response from exerting anti-tumor effects [76][77].

CSC niches have been identified in a number of human cancer types, such as esophageal [78], gastric [79], colorectal [80], liver [81], pancreatic [82], breast [83], ovarian [84], prostate [85], renal [86], brain [87], head and neck [88], lung [89], or melanoma [90]. Numerous studies have examined the similarities and variations between the habitats of various malignancies, as well as the effect of cancer-specific microenvironments on the establishment and growth of CSCs [91][92][93][94][95][96][97].

In the microenvironment of the liver, CSCs promote pro-tumor TME formation in several ways, such as the production of the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1) or the activation of the hepatocyte-derived growth factor/hepatocyte-derived growth factor receptor (HGF/HGFR) system by the hypoxia-induced activation of HIF1. Kupffer cells and neutrophils enhance tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α, IL1, and MMP9 production as well [98]. The production of growth factors (e.g., epidermal growth factor receptor /EGFR/, VEGF, PDGF, and stromal cell-derived factor 1 /SDF1/), TNF, and other angiogenic factors also promotes the growth and survival of CSCs and their resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy [99][100][101][102]. A number of surface markers are known for CSCs in liver cancer (e.g., CD133, CD90, CD24, CD13, epithelial cell adhesion molecule /EpCAM/, aldehyde dehydrogenase /ALDH/, and hepatic progenitor cell marker OV-6). The expression of stem cell markers confers different properties to CSCs. In CD90+ cells, genes associated with inflammation and drug resistance are upregulated, whereas CD133+ cells are resistant to apoptosis and radiotherapy through activation of the Ak strain transforming/Protein kinase B (Akt/PKB) pathway [103][104].

4. Emergence of CSC Phenotype without TME

5. Utilization of the Inflammatory Process in Cancer Therapy

References

- Gasch, C.; Ffrench, B.; O’Leary, J.J.; Gallagher, M.F. Catching moving targets: Cancer stem cell hierarchies, therapy-resistance & considerations for clinical intervention. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 43.

- Rich, J.N. Cancer stem cells: Understanding tumor hierarchy and heterogeneity. Medicine 2016, 95 (Suppl. 1), S2–S7.

- Chaffer, C.L.; Brueckmann, I.; Scheel, C.; Kaestli, A.J.; Wiggins, P.A.; Rodrigues, L.O.; Brooks, M.; Reinhardt, F.; Su, Y.; Polyak, K.; et al. Normal and neoplastic nonstem cells can spontaneously convert to a stem-like state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 7950–7955.

- Bonde, A.K.; Tischler, V.; Kumar, S.; Soltermann, A.; Schwendener, R.A. Intratumoral macrophages contribute to epithelial-mesenchymal transition in solid tumors. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 35.

- Bao, S.; Wu, Q.; McLendon, R.E.; Hao, Y.; Shi, Q.; Hjelmeland, A.B.; Dewhirst, M.W.; Bigner, D.D.; Rich, J.N. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature 2006, 444, 756–760.

- Blanpain, C.; Mohrin, M.; Sotiropoulou, P.A.; Passegué, E. DNA-damage response in tissue-specific and cancer stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2011, 8, 16–29.

- Begicevic, R.R.; Falasca, M. ABC Transporters in Cancer Stem Cells: Beyond Chemoresistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2362.

- Pastò, A.; Consonni, F.M.; Sica, A. Influence of Innate Immunity on Cancer Cell Stemness. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3352.

- Di Tomaso, T.; Mazzoleni, S.; Wang, E.; Sovena, G.; Clavenna, D.; Franzin, A.; Mortini, P.; Ferrone, S.; Doglioni, C.; Marincola, F.M.; et al. Immunobiological characterization of cancer stem cells isolated from glioblastoma patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 800–813.

- Schatton, T.; Schütte, U.; Frank, N.Y.; Zhan, Q.; Hoerning, A.; Robles, S.C.; Zhou, J.; Hodi, F.S.; Spagnoli, G.C.; Murphy, G.F.; et al. Modulation of T-cell activation by malignant melanoma initiating cells. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 697–708.

- Volonté, A.; Di Tomaso, T.; Spinelli, M.; Todaro, M.; Sanvito, F.; Albarello, L.; Bissolati, M.; Ghirardelli, L.; Orsenigo, E.; Ferrone, S.; et al. Cancer-initiating cells from colorectal cancer patients escape from T cell-mediated immunosurveillance in vitro through membrane-bound IL-4. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 523–532.

- Shang, B.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, S.J.; Liu, Y. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15179.

- Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Yu, S.C.; Ping, Y.F.; Yang, J.; Xu, S.L.; Ye, X.Z.; Xu, C.; et al. Metastatic consequences of immune escape from NK cell cytotoxicity by human breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 5746–5757.

- Bruttel, V.S.; Wischhusen, J. Cancer stem cell immunology: Key to understanding tumorigenesis and tumor immune escape? Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 360.

- Drukker, M.; Katz, G.; Urbach, A.; Schuldiner, M.; Markel, G.; Itskovitz-Eldor, J.; Reubinoff, B.; Mandelboim, O.; Benvenisty, N. Characterization of the expression of MHC proteins in human embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 9864–9869.

- Relation, T.; Dominici, M.; Horwitz, E.M. Concise Review: An (Im)Penetrable Shield: How the Tumor Microenvironment Protects Cancer Stem Cells. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 1123–1130.

- Ju, F.; Atyah, M.M.; Horstmann, N.; Gul, S.; Vago, R.; Bruns, C.J.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, Q.Z.; Ren, N. Characteristics of the cancer stem cell niche and therapeutic strategies. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 233.

- Maccalli, C.; Rasul, K.I.; Elawad, M.; Ferrone, S. The role of cancer stem cells in the modulation of anti-tumor immune responses. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 53, 189–200.

- Shlush, L.I.; Chapal-Ilani, N.; Adar, R.; Pery, N.; Maruvka, Y.; Spiro, A.; Shouval, R.; Rowe, J.M.; Tzukerman, M.; Bercovich, D.; et al. Cell lineage analysis of acute leukemia relapse uncovers the role of replication-rate heterogeneity and microsatellite instability. Blood 2012, 120, 603–612.

- Vahidian, F.; Duijf, P.H.G.; Safarzadeh, E.; Derakhshani, A.; Baghbanzadeh, A.; Baradaran, B. Interactions between cancer stem cells, immune system and some environmental components: Friends or foes? Immunol. Lett. 2019, 208, 19–29.

- De Vlaeminck, Y.; González-Rascón, A.; Goyvaerts, C.; Breckpot, K. Cancer-Associated Myeloid Regulatory Cells. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 113.

- Mantovani, A.; Marchesi, F.; Malesci, A.; Laghi, L.; Allavena, P. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 399–416.

- Ruffell, B.; Chang-Strachan, D.; Chan, V.; Rosenbusch, A.; Ho, C.M.; Pryer, N.; Daniel, D.; Hwang, E.S.; Rugo, H.S.; Coussens, L.M. Macrophage IL-10 blocks CD8+ T cell-dependent responses to chemotherapy by suppressing IL-12 expression in intratumoral dendritic cells. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 623–637.

- Tauriello, D.V.F.; Palomo-Ponce, S.; Stork, D.; Berenguer-Llergo, A.; Badia-Ramentol, J.; Iglesias, M.; Sevillano, M.; Ibiza, S.; Cañellas, A.; Hernando-Momblona, X.; et al. TGFβ drives immune evasion in genetically reconstituted colon cancer metastasis. Nature 2018, 554, 538–543.

- Gabrilovich, D.I.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Bronte, V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 12, 253–268.

- Fridlender, Z.G.; Sun, J.; Kim, S.; Kapoor, V.; Cheng, G.; Ling, L.; Worthen, G.S.; Albelda, S.M. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 183–194.

- Sica, A.; Guarneri, V.; Gennari, A. Myelopoiesis, metabolism and therapy: A crucial crossroads in cancer progression. Cell Stress 2019, 3, 284–294.

- Strauss, L.; Sangaletti, S.; Consonni, F.M.; Szebeni, G.; Morlacchi, S.; Totaro, M.G.; Porta, C.; Anselmo, A.; Tartari, S.; Doni, A.; et al. RORC1 Regulates Tumor-Promoting “Emergency” Granulo-Monocytopoiesis. Cancer Cell 2015, 28, 253–269.

- Ueha, S.; Shand, F.H.; Matsushima, K. Myeloid cell population dynamics in healthy and tumor-bearing mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2011, 11, 783–788.

- Velten, L.; Haas, S.F.; Raffel, S.; Blaszkiewicz, S.; Islam, S.; Hennig, B.P.; Hirche, C.; Lutz, C.; Buss, E.C.; Nowak, D.; et al. Human haematopoietic stem cell lineage commitment is a continuous process. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 271–281.

- Sica, A.; Bronte, V. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1155–1166.

- Ravindran, S.; Rasool, S.; Maccalli, C. The Cross Talk between Cancer Stem Cells/Cancer Initiating Cells and Tumor Microenvironment: The Missing Piece of the Puzzle for the Efficient Targeting of these Cells with Immunotherapy. Cancer Microenviron. 2019, 12, 133–148.

- Lau, E.Y.; Ho, N.P.; Lee, T.K. Cancer Stem Cells and Their Microenvironment: Biology and Therapeutic Implications. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 3714190.

- Inamoto, S.; Itatani, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Minamiguchi, S.; Hirai, H.; Iwamoto, M.; Hasegawa, S.; Taketo, M.M.; Sakai, Y.; Kawada, K. Loss of SMAD4 Promotes Colorectal Cancer Progression by Accumulation of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells through the CCL15-CCR1 Chemokine Axis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 492–501.

- Panni, R.Z.; Sanford, D.E.; Belt, B.A.; Mitchem, J.B.; Worley, L.A.; Goetz, B.D.; Mukherjee, P.; Wang-Gillam, A.; Link, D.C.; Denardo, D.G.; et al. Tumor-induced STAT3 activation in monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells enhances stemness and mesenchymal properties in human pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2014, 63, 513–528.

- Wang, Y.; Yin, K.; Tian, J.; Xia, X.; Ma, J.; Tang, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, S. Granulocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Promote the Stemness of Colorectal Cancer Cells through Exosomal S100A9. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1901278.

- Whiteside, T.L. Regulatory T cell subsets in human cancer: Are they regulating for or against tumor progression? Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2014, 63, 67–72.

- Arneth, B. Tumor Microenvironment. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019, 56, 15.

- Hirahara, K.; Poholek, A.; Vahedi, G.; Laurence, A.; Kanno, Y.; Milner, J.D.; O’Shea, J.J. Mechanisms underlying helper T-cell plasticity: Implications for immune-mediated disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, 1276–1287.

- Cuiffo, B.G.; Campagne, A.; Bell, G.W.; Lembo, A.; Orso, F.; Lien, E.C.; Bhasin, M.K.; Raimo, M.; Hanson, S.E.; Marusyk, A.; et al. MSC-regulated microRNAs converge on the transcription factor FOXP2 and promote breast cancer metastasis. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 15, 762–774.

- Gwak, J.M.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, E.J.; Chung, Y.R.; Yun, S.; Seo, A.N.; Lee, H.J.; Park, S.Y. MicroRNA-9 is associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition, breast cancer stem cell phenotype, and tumor progression in breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 147, 39–49.

- Frisbie, L.; Buckanovich, R.J.; Coffman, L. Carcinoma-Associated Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells: Architects of the Pro-tumorigenic Tumor Microenvironment. Stem Cells 2022, 40, 705–715.

- Roodhart, J.M.; Daenen, L.G.; Stigter, E.C.; Prins, H.J.; Gerrits, J.; Houthuijzen, J.M.; Gerritsen, M.G.; Schipper, H.S.; Backer, M.J.; van Amersfoort, M.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells induce resistance to chemotherapy through the release of platinum-induced fatty acids. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 370–383.

- van der Velden, D.L.; Cirkel, G.A.; Houthuijzen, J.M.; van Werkhoven, E.; Roodhart, J.M.L.; Daenen, L.G.M.; Kaing, S.; Gerrits, J.; Verhoeven-Duif, N.M.; Grootscholten, C.; et al. Phase I study of combined indomethacin and platinum-based chemotherapy to reduce platinum-induced fatty acids. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2018, 81, 911–921.

- Mallampati, S.; Leng, X.; Ma, H.; Zeng, J.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Lin, K.; Lu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Sun, B.; et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors induce mesenchymal stem cell-mediated resistance in BCR-ABL+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2015, 125, 2968–2973.

- Xue, B.Z.; Xiang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.F.; Zhou, Y.J.; Tian, H.; Abdelmaksou, A.; Xue, J.; Sun, M.X.; Yi, D.Y.; et al. CD90low glioma-associated mesenchymal stromal/stem cells promote temozolomide resistance by activating FOXS1-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition in glioma cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 394.

- Eliason, S.; Hong, L.; Sweat, Y.; Chalkley, C.; Cao, H.; Liu, Q.; Qi, H.; Xu, H.; Zhan, F.; Amendt, B.A. Extracellular vesicle expansion of PMIS-miR-210 expression inhibits colorectal tumour growth via apoptosis and an XIST/NME1 regulatory mechanism. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e1037.

- Ji, R.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.; Xue, J.; Yuan, X.; Yan, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhu, W.; Qian, H.; Xu, W. Exosomes derived from human mesenchymal stem cells confer drug resistance in gastric Cancer. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 2473–2483.

- Naito, Y.; Yoshioka, Y.; Ochiya, T. Intercellular crosstalk between cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts via extracellular vesicles. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 367.

- Kondo, R.; Sakamoto, N.; Harada, K.; Hashimoto, H.; Morisue, R.; Yanagihara, K.; Kinoshita, T.; Kojima, M.; Ishii, G. Cancer-associated fibroblast-dependent and -independent invasion of gastric cancer cells. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2022.

- Chen, W.J.; Ho, C.C.; Chang, Y.L.; Chen, H.Y.; Lin, C.A.; Ling, T.Y.; Yu, S.L.; Yuan, S.S.; Chen, Y.J.; Lin, C.Y.; et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts regulate the plasticity of lung cancer stemness via paracrine signalling. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3472.

- Lau, E.Y.; Lo, J.; Cheng, B.Y.; Ma, M.K.; Lee, J.M.; Ng, J.K.; Chai, S.; Lin, C.H.; Tsang, S.Y.; Ma, S.; et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Regulate Tumor-Initiating Cell Plasticity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma through c-Met/FRA1/HEY1 Signaling. Cell Rep. 2016, 15, 1175–1189.

- Chan, T.S.; Hsu, C.C.; Pai, V.C.; Liao, W.Y.; Huang, S.S.; Tan, K.T.; Yen, C.J.; Hsu, S.C.; Chen, W.Y.; Shan, Y.S.; et al. Metronomic chemotherapy prevents therapy-induced stromal activation and induction of tumor-initiating cells. J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 2967–2988.

- Wilczyński, J.R.; Wilczyński, M.; Paradowska, E. Cancer Stem Cells in Ovarian Cancer-A Source of Tumor Success and a Challenging Target for Novel Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2496.

- Zhou, W.; Ke, S.Q.; Huang, Z.; Flavahan, W.; Fang, X.; Paul, J.; Wu, L.; Sloan, A.E.; McLendon, R.E.; Li, X.; et al. Periostin secreted by glioblastoma stem cells recruits M2 tumour-associated macrophages and promotes malignant growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 170–182.

- Wu, A.; Wei, J.; Kong, L.Y.; Wang, Y.; Priebe, W.; Qiao, W.; Sawaya, R.; Heimberger, A.B. Glioma cancer stem cells induce immunosuppressive macrophages/microglia. Neuro Oncol. 2010, 12, 1113–1125.

- Zhang, Q.; Cai, D.J.; Li, B. Ovarian cancer stem-like cells elicit the polarization of M2 macrophages. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 4685–4693.

- Nusblat, L.M.; Carroll, M.J.; Roth, C.M. Crosstalk between M2 macrophages and glioma stem cells. Cell. Oncol. 2017, 40, 471–482.

- Kokubu, Y.; Tabu, K.; Muramatsu, N.; Wang, W.; Murota, Y.; Nobuhisa, I.; Jinushi, M.; Taga, T. Induction of protumoral CD11c(high) macrophages by glioma cancer stem cells through GM-CSF. Genes Cells 2016, 21, 241–251.

- Elaimy, A.L.; Guru, S.; Chang, C.; Ou, J.; Amante, J.J.; Zhu, L.J.; Goel, H.L.; Mercurio, A.M. VEGF-neuropilin-2 signaling promotes stem-like traits in breast cancer cells by TAZ-mediated repression of the Rac GAP β2-chimaerin. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11, eaao6897.

- Mercurio, A.M. VEGF/Neuropilin Signaling in Cancer Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 490.

- Raghavan, S.; Mehta, P.; Xie, Y.; Lei, Y.L.; Mehta, G. Ovarian cancer stem cells and macrophages reciprocally interact through the WNT pathway to promote pro-tumoral and malignant phenotypes in 3D engineered microenvironments. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 190.

- Gabrusiewicz, K.; Li, X.; Wei, J.; Hashimoto, Y.; Marisetty, A.L.; Ott, M.; Wang, F.; Hawke, D.; Yu, J.; Healy, L.M.; et al. Glioblastoma stem cell-derived exosomes induce M2 macrophages and PD-L1 expression on human monocytes. Oncoimmunology 2018, 7, e1412909.

- Domenis, R.; Cesselli, D.; Toffoletto, B.; Bourkoula, E.; Caponnetto, F.; Manini, I.; Beltrami, A.P.; Ius, T.; Skrap, M.; Di Loreto, C.; et al. Systemic T Cells Immunosuppression of Glioma Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Is Mediated by Monocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169932.

- Biswas, S.; Mandal, G.; Roy Chowdhury, S.; Purohit, S.; Payne, K.K.; Anadon, C.; Gupta, A.; Swanson, P.; Yu, X.; Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; et al. Exosomes Produced by Mesenchymal Stem Cells Drive Differentiation of Myeloid Cells into Immunosuppressive M2-Polarized Macrophages in Breast Cancer. J. Immunol. 2019, 203, 3447–3460.

- Grange, C.; Tapparo, M.; Tritta, S.; Deregibus, M.C.; Battaglia, A.; Gontero, P.; Frea, B.; Camussi, G. Role of HLA-G and extracellular vesicles in renal cancer stem cell-induced inhibition of dendritic cell differentiation. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 1009.

- Hwang, W.L.; Lan, H.Y.; Cheng, W.C.; Huang, S.C.; Yang, M.H. Tumor stem-like cell-derived exosomal RNAs prime neutrophils for facilitating tumorigenesis of colon Cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 10.

- Anselmi, M.; Fontana, F.; Marzagalli, M.; Gagliano, N.; Sommariva, M.; Limonta, P. Melanoma Stem Cells Educate Neutrophils to Support Cancer Progression. Cancers 2022, 14, 3391.

- Műzes, G.; Sipos, F. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Secretome: A Potential Therapeutic Option for Autoimmune and Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 2300.

- Lasorella, A.; Benezra, R.; Iavarone, A. The ID proteins: Master regulators of cancer stem cells and tumour aggressiveness. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 77–91.

- Cheng, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Wu, Q.; Donnola, S.; Liu, J.K.; Fang, X.; Sloan, A.E.; Mao, Y.; Lathia, J.D.; et al. Glioblastoma stem cells generate vascular pericytes to support vessel function and tumor growth. Cell 2013, 153, 139–152.

- Dianat-Moghadam, H.; Heidarifard, M.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, R.; Panahi, Y.; Hamishehkar, H.; Pouremamali, F.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Nouri, M. Cancer stem cells-emanated therapy resistance: Implications for liposomal drug delivery systems. J. Control. Re-lease 2018, 288, 62–83.

- Lytle, N.K.; Barber, A.G.; Reya, T. Stem cell fate in cancer growth, progression and therapy resistance. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 669–680.

- Najafi, M.; Farhood, B.; Mortezaee, K. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) in cancer progression and therapy. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 8381–8395.

- Ji, C.; Yang, L.; Yi, W.; Xiang, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Qian, F.; Ren, Y.; Cui, W.; Zhang, X.; et al. Capillary morphogenesis gene 2 maintains gastric cancer stem-like cell phenotype by activating a Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Oncogene 2018, 37, 3953–3966.

- Zhao, H.; Wu, L.; Yan, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y. Inflammation and tumor progression: Signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 263.

- Tiwari, A.; Trivedi, R.; Lin, S.Y. Tumor microenvironment: Barrier or opportunity towards effective cancer therapy. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 83.

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, L.; Ge, D.; Tan, L.; Cao, B.; Fan, H.; Xue, L. Exosomal O-GlcNAc transferase from esophageal carcinoma stem cell promotes cancer immunosuppression through up-regulation of PD-1 in CD8+ T cells. Cancer Lett. 2021, 500, 98–106.

- Hayakawa, Y.; Ariyama, H.; Stancikova, J.; Sakitani, K.; Asfaha, S.; Renz, B.W.; Dubeykovskaya, Z.A.; Shibata, W.; Wang, H.; Westphalen, C.B.; et al. Mist1 Expressing Gastric Stem Cells Maintain the Normal and Neoplastic Gastric Epithelium and Are Supported by a Perivascular Stem Cell Niche. Cancer Cell 2015, 28, 800–814.

- Sphyris, N.; Hodder, M.C.; Sansom, O.J. Subversion of Niche-Signalling Pathways in Colorectal Cancer: What Makes and Breaks the Intestinal Stem Cell. Cancers 2021, 13, 1000.

- Li, Y.; Tang, T.; Lee, H.J.; Song, K. Selective Anti-Cancer Effects of Plasma-Activated Medium and Its High Efficacy with Cisplatin on Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Cancer Stem Cell Characteristics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3956.

- Nimmakayala, R.K.; Leon, F.; Rachagani, S.; Rauth, S.; Nallasamy, P.; Marimuthu, S.; Shailendra, G.K.; Chhonker, Y.S.; Chugh, S.; Chirravuri, R.; et al. Metabolic programming of distinct cancer stem cells promotes metastasis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene 2021, 40, 215–231.

- Lin, X.; Chen, W.; Wei, F.; Xie, X. TV-circRGPD6 Nanoparticle Suppresses Breast Cancer Stem Cell-Mediated Metastasis via the miR-26b/YAF2 Axis. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 244–262.

- Jain, S.; Annett, S.L.; Morgan, M.P.; Robson, T. The Cancer Stem Cell Niche in Ovarian Cancer and Its Impact on Immune Surveillance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4091.

- Hagiwara, M.; Yasumizu, Y.; Yamashita, N.; Rajabi, H.; Fushimi, A.; Long, M.D.; Li, W.; Bhattacharya, A.; Ahmad, R.; Oya, M.; et al. MUC1-C Activates the BAF (mSWI/SNF) Complex in Prostate Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 1111–1122.

- Fendler, A.; Bauer, D.; Busch, J.; Jung, K.; Wulf-Goldenberg, A.; Kunz, S.; Song, K.; Myszczyszyn, A.; Elezkurtaj, S.; Erguen, B.; et al. Inhibiting WNT and NOTCH in renal cancer stem cells and the implications for human patients. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 929.

- Gimple, R.C.; Bhargava, S.; Dixit, D.; Rich, J.N. Glioblastoma stem cells: Lessons from the tumor hierarchy in a lethal Cancer. Genes Dev. 2019, 33, 591–609.

- Liu, C.; Billet, S.; Choudhury, D.; Cheng, R.; Haldar, S.; Fernandez, A.; Biondi, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Bhowmick, N.A. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells interact with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells to promote cancer progression and drug resistance. Neoplasia 2021, 23, 118–128.

- Raniszewska, A.; Vroman, H.; Dumoulin, D.; Cornelissen, R.; Aerts, J.G.J.V.; Domagała-Kulawik, J. PD-L1+ lung cancer stem cells modify the metastatic lymph-node immunomicroenvironment in nsclc patients. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2021, 70, 453–461.

- Hsu, M.Y.; Yang, M.H.; Schnegg, C.I.; Hwang, S.; Ryu, B.; Alani, R.M. Notch3 signaling-mediated melanoma-endothelial crosstalk regulates melanoma stem-like cell homeostasis and niche morphogenesis. Lab. Investig. 2017, 97, 725–736.

- Lacina, L.; Plzak, J.; Kodet, O.; Szabo, P.; Chovanec, M.; Dvorankova, B.; Smetana, K., Jr. Cancer Microenvironment: What Can We Learn from the Stem Cell Niche. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 24094–24110.

- Pinho, S.; Frenette, P.S. Haematopoietic stem cell activity and interactions with the niche. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 303–320.

- Tabu, K.; Taga, T. Cancer ego-system in glioma: An iron-replenishing niche network systemically self-organized by cancer stem cells. Inflamm. Regen. 2022, 42, 54.

- Kim, M.; Jo, K.W.; Kim, H.; Han, M.E.; Oh, S.O. Genetic heterogeneity of liver cancer stem cells. Anat. Cell Biol. 2022.

- Pedersen, R.K.; Andersen, M.; Skov, V.; Kjær, L.; Hasselbalch, H.C.; Ottesen, J.T.; Stiehl, T. HSC niche dynamics in regeneration, pre-malignancy and cancer: Insights from mathematical modeling. Stem Cells 2022, sxac079.

- Akindona, F.A.; Frederico, S.C.; Hancock, J.C.; Gilbert, M.R. Exploring the origin of the cancer stem cell niche and its role in anti-angiogenic treatment for glioblastoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 947634.

- Luo, S.; Yang, G.; Ye, P.; Cao, N.; Chi, X.; Yang, W.H.; Yan, X. Macrophages Are a Double-Edged Sword: Molecular Crosstalk between Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Cancer Stem Cells. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 850.

- Yang, L.; Shi, P.; Zhao, G.; Xu, J.; Peng, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X.; Dong, Z.; Chen, F.; et al. Targeting cancer stem cell pathways for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 8.

- Nakamura, T.; Sakai, K.; Nakamura, T.; Matsumoto, K. Hepatocyte growth factor twenty years on: Much more than a growth factor. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 26 (Suppl. 1), 188–202.

- Lau, C.K.; Yang, Z.F.; Ho, D.W.; Ng, M.N.; Yeoh, G.C.; Poon, R.T.; Fan, S.T. An Akt/hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha/platelet-derived growth factor-BB autocrine loop mediates hypoxia-induced chemoresistance in liver cancer cells and tumorigenic hepatic progenitor cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 3462–3471.

- Wang, X.; Sun, W.; Shen, W.; Xia, M.; Chen, C.; Xiang, D.; Ning, B.; Cui, X.; Li, H.; Li, X.; et al. Long non-coding RNA DILC regulates liver cancer stem cells via IL-6/STAT3 axis. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1283–1294.

- Liu, G.; Yang, Z.F.; Sun, J.; Sun, B.Y.; Zhou, P.Y.; Zhou, C.; Guan, R.Y.; Wang, Z.T.; Yi, Y.; Qiu, S.J. The LINC00152/miR-205-5p/CXCL11 axis in hepatocellular carcinoma cancer-associated fibroblasts affects cancer cell phenotypes and tumor growth. Cell Oncol. 2022, 45, 1435–1449.

- Huang, H.; Hu, M.; Li, P.; Lu, C.; Li, M. Mir-152 inhibits cell proliferation and colony formation of CD133(+) liver cancer stem cells by targeting KIT. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 921–928.

- Sukowati, C.H.; Tiribelli, C. The biological implication of cancer stem cells in hepatocellular carcinoma: A possible target for future therapy. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 7, 749–757.

- Műzes, G.; Bohusné Barta, B.; Szabó, O.; Horgas, V.; Sipos, F. Cell-Free DNA in the Pathogenesis and Therapy of Non-Infectious Inflammations and Tumors. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2853.

- Sipos, F.; Kiss, A.L.; Constantinovits, M.; Tulassay, Z.; Műzes, G. Modified Genomic Self-DNA Influences In Vitro Survival of HT29 Tumor Cells via TLR9- and Autophagy Signaling. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2019, 25, 1505–1517.

- Sipos, F.; Bohusné Barta, B.; Simon, Á.; Nagy, L.; Dankó, T.; Raffay, R.E.; Petővári, G.; Zsiros, V.; Wichmann, B.; Sebestyén, A.; et al. Survival of HT29 Cancer Cells Is Affected by IGF1R Inhibition via Modulation of Self-DNA-Triggered TLR9 Signaling and the Autophagy Response. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2022, 28, 1610322.

- Qi, Y.; Zou, H.; Zhao, X.; Kapeleris, J.; Monteiro, M.; Li, F.; Xu, Z.P.; Deng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Tang, Y.; et al. Inhibition of colon cancer K-RasG13D mutation reduces cancer cell proliferation but promotes stemness and inflammation via RAS/ERK pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 996053.

- Karami Fath, M.; Ebrahimi, M.; Nourbakhsh, E.; Zia Hazara, A.; Mirzaei, A.; Shafieyari, S.; Salehi, A.; Hoseinzadeh, M.; Payandeh, Z.; Barati, G. PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in cancer stem cells. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2022, 237, 154010.

- Nengroo, M.A.; Verma, A.; Datta, D. Cytokine chemokine network in tumor microenvironment: Impact on CSC properties and therapeutic applications. Cytokine 2022, 156, 155916.

- Zhang, D.; Tang, D.G.; Rycaj, K. Cancer stem cells: Regulation programs, immunological properties and immunotherapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018, 52, 94–106.

- Mortezaee, K. Human hepatocellular carcinoma: Protection by melatonin. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 6486–6508.

- Zappasodi, R.; Budhu, S.; Hellmann, M.D.; Postow, M.A.; Senbabaoglu, Y.; Manne, S.; Gasmi, B.; Liu, C.; Zhong, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Non-conventional Inhibitory CD4+Foxp3-PD-1hi T Cells as a Biomarker of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Activity. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 1017–1032.e7.

- Du, X.; Tang, F.; Liu, M.; Su, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.; Devenport, M.; Lazarski, C.A.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X.; et al. A reappraisal of CTLA-4 checkpoint blockade in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 416–432.

- Loh, J.J.; Ma, S. The Role of Cancer-Associated Fibroblast as a Dynamic Player in Mediating Cancer Stemness in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 727640.

- Pienta, K.J.; Machiels, J.P.; Schrijvers, D.; Alekseev, B.; Shkolnik, M.; Crabb, S.J.; Li, S.; Seetharam, S.; Puchalski, T.A.; Takimoto, C.; et al. Phase 2 study of carlumab (CNTO 888), a human monoclonal antibody against CC-chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), in metastatic castration-resistant prostate Cancer. Investig. New Drugs 2013, 31, 760–768.

- Calon, A.; Lonardo, E.; Berenguer-Llergo, A.; Espinet, E.; Hernando-Momblona, X.; Iglesias, M.; Sevillano, M.; Palomo-Ponce, S.; Tauriello, D.V.; Byrom, D.; et al. Stromal gene expression defines poor-prognosis subtypes in colorectal Cancer. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 320–329.

- Ferrer-Mayorga, G.; Gómez-López, G.; Barbáchano, A.; Fernández-Barral, A.; Peña, C.; Pisano, D.G.; Cantero, R.; Rojo, F.; Muñoz, A.; Larriba, M.J. Vitamin D receptor expression and associated gene signature in tumour stromal fibroblasts predict clinical outcome in colorectal Cancer. Gut 2017, 66, 1449–1462.

- Kocher, H.M.; Basu, B.; Froeling, F.E.M.; Sarker, D.; Slater, S.; Carlin, D.; deSouza, N.M.; De Paepe, K.N.; Goulart, M.R.; Hughes, C.; et al. Phase I clinical trial repurposing all-trans retinoic acid as a stromal targeting agent for pancreatic Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4841.

- Biffi, G.; Oni, T.E.; Spielman, B.; Hao, Y.; Elyada, E.; Park, Y.; Preall, J.; Tuveson, D.A. IL1-Induced JAK/STAT Signaling Is Antagonized by TGFβ to Shape CAF Heterogeneity in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 282–301.

- Galbo, P.M., Jr.; Zang, X.; Zheng, D. Molecular Features of Cancer-associated Fibroblast Subtypes and their Implication on Cancer Pathogenesis, Prognosis, and Immunotherapy Resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 2636–2647.

- Ribatti, D.; Solimando, A.G.; Pezzella, F. The Anti-VEGF(R) Drug Discovery Legacy: Improving Attrition Rates by Breaking the Vicious Cycle of Angiogenesis in Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 3433.