Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Moussa Ide Nasser | -- | 2989 | 2023-01-05 02:52:48 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 2989 | 2023-01-05 03:22:44 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Wang, B.; Gan, L.; Deng, Y.; Zhu, S.; Li, G.; Nasser, M.I.; Liu, N.; Zhu, P. Cardiovascular Disease and Exercise. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39769 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Wang B, Gan L, Deng Y, Zhu S, Li G, Nasser MI, et al. Cardiovascular Disease and Exercise. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39769. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Wang, Bo, Lin Gan, Yuzhi Deng, Shuoji Zhu, Ge Li, Moussa Ide Nasser, Nanbo Liu, Ping Zhu. "Cardiovascular Disease and Exercise" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39769 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Wang, B., Gan, L., Deng, Y., Zhu, S., Li, G., Nasser, M.I., Liu, N., & Zhu, P. (2023, January 05). Cardiovascular Disease and Exercise. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39769

Wang, Bo, et al. "Cardiovascular Disease and Exercise." Encyclopedia. Web. 05 January, 2023.

Copy Citation

Inactivity is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Exercise may greatly enhance the metabolism and function of the cardiovascular system, lower several risk factors, and prevent the development and treatment of cardiovascular disease while delivering easy, physical, and emotional enjoyment. Exercise regulates the cardiovascular system by reducing oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, regulating cardiovascular insulin sensitivity and the body’s metabolism, promoting stem cell mobilization, strengthening autophagy and myocardial mitochondrial function, and enhancing cardiovascular damage resistance, among other effects.

exercise factor

cardiac protection

mitochondria

insulin sensitivity

1. Introduction

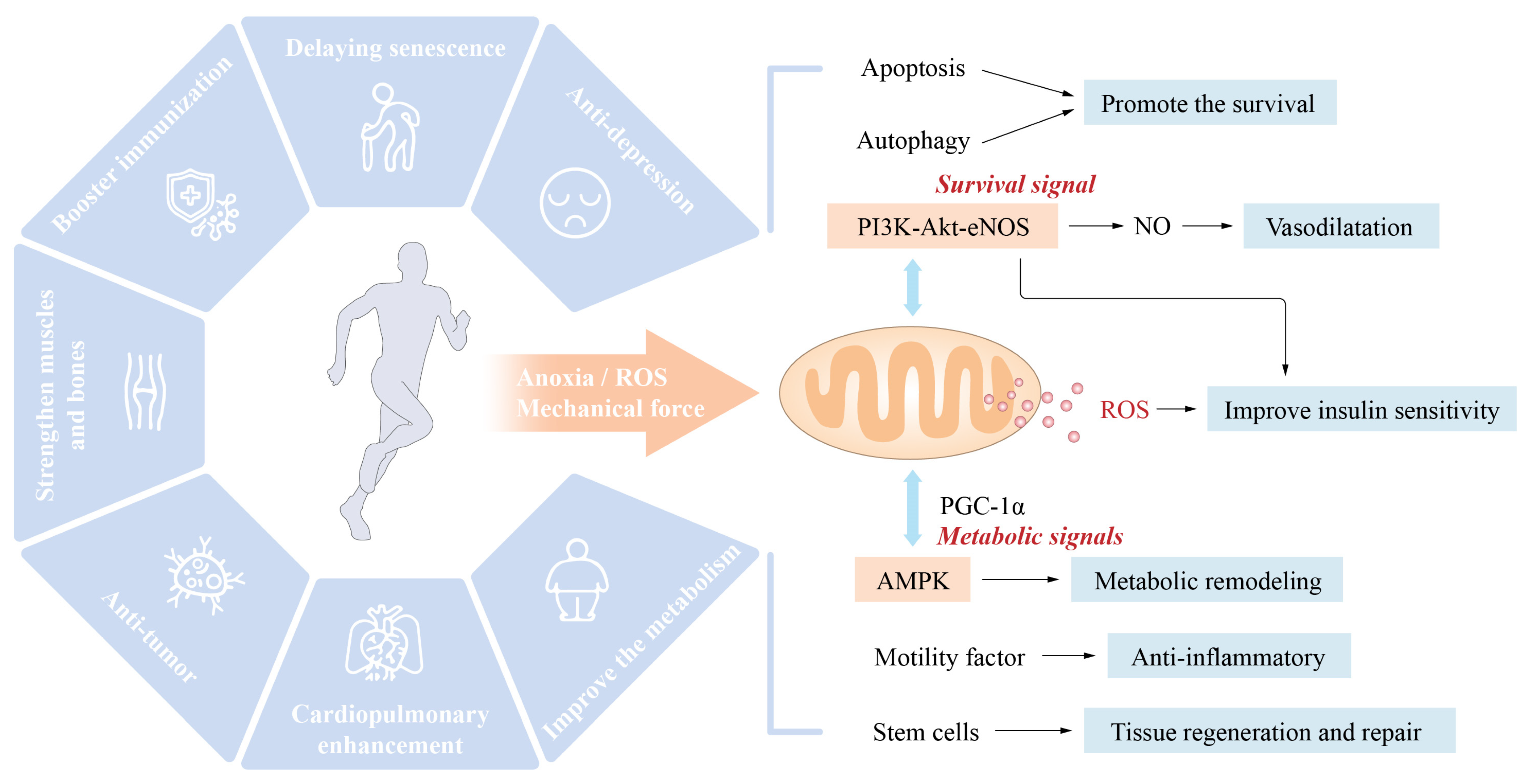

The beneficial effects of exercise on cardiovascular health are generally recognized, but the mechanisms underlying their benefits remain obscure. Physical activity boosts cardiovascular health by a systemic action, including the metabolism of neurons and endocrine, immunological, and other systems [1][2]. The essence of this effect is the activation of endogenous protective mechanisms due to a lack of oxygen, oxidative stress, and mechanical force stimulation (such as flow acceleration), such as the activation of cell survival signals, which upregulate the body’s metabolism, enhance the antioxidant capacity and promote stem cell mobilization.

Mitochondria are vital organelles that mediate the body’s response to movement. The promotion of mitochondrial synthesis and enhancement of mitochondrial function through signalling molecules such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-coactivator-1 (PCC-1) is essential for the health benefits of exercise [3][4]. According to Wang et al. [5], cardiomyocyte apoptosis and vascular endothelial dysfunction might result in detrimental cardiovascular system remodeling, leading to the onset and progression of IHD. Exercise intervention primarily activated the PI3K/Akt pathway, raised the amount of anti-apoptotic factors, decreased pro-apoptotic factors, and greatly lowered cardiomyocyte apoptosis and unfavorable remodeling. By activating the PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway, the level of NO can be increased, endothelial cell proliferation and migration can be stimulated, damaged endothelial cells can be repaired, the vascular endothelial function can be enhanced, the progression of IHD can be stabilized, and the disease state can even be reversed. Similarly, moderate aerobic exercise (16 m/min, 60 min/d, 5 days/wk) can activate the neuregulin-1 (NRG1)/epidermal growth factor receptor, ErbB, and fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21)/PI3K/AKT to inhibit myocardial apoptosis, reduce the MI area, reduce myocardial fibrosis, and promote cardiac repair and angiogenesis, and improve heart disease’s rational remodeling and cardiac function [6]. Whereas, long-term and intensive aerobic activity may cause physiological hypertrophy of the heart and thereby enhance cardiac function. In contrast to pathological hypertrophy, physiological hypertrophy is not accompanied by pathological changes such as cardiac fibrosis. This type of exercise strongly triggers the IGF1-PI3K-Akt signalling pathway in the myocardium [7] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Exercise-induced health effects and central role of mitochondria: Hypoxia, oxidative stress, mechanical force, and other variables play a role in activating endogenous defensive systems when exercise is performed. These endogenous defensive mechanisms include the survival signalling pathways of PI3K-Akt-eNOS-NO and the metabolic signalling pathways of PGC-1-AMPK-mTOR. Mitochondria are an extremely important factor in the positive health impacts of exercise.

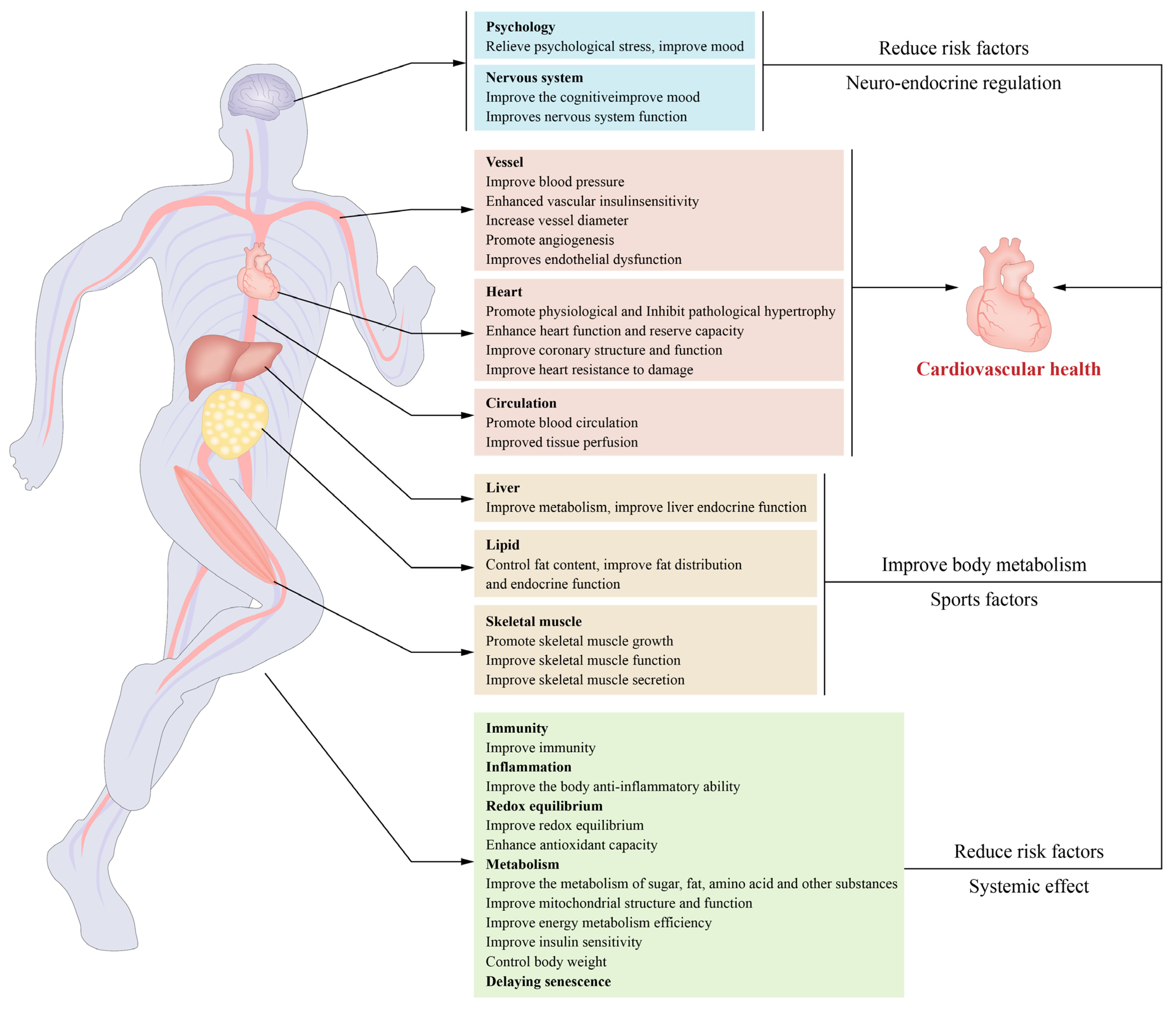

In addition, exercise may lower cardiovascular disease risk factors, modify the cardiovascular structure and function, and enhance insulin sensitivity and loss resistance, among other effects. Exercise-related molecule production by numerous tissues and organs contributes to metabolism and cardiovascular protection, highlighting the relevance of crosstalk between tissues and organs in the exercise-induced improvement of cardiovascular health.

2. Exercise Reduces the Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease and Its Main Mechanism

2.1. Exercise Improves the Body’s Metabolism

Metabolic syndrome, which is characterized by obesity, hyperlipidemia, impaired glucose tolerance, and insulin resistance, is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and coronary heart disease. Various forms of exercise may improve glucose, lipid, and insulin sensitivity [8]. The molecular benefits include significantly lowered triglycerides, increased high-density lipoprotein levels, accelerated browning and thermogenesis in adipose tissue, enhanced fatty acid metabolism, increased muscle mass, and decreased body fat. A recent study has shown that the metabolic imbalance of amino acids is a major cause of cardiovascular and metabolic illness. Exercise may alleviate the metabolic problem of basal and branched-amino acids (BCAA) in pathological situations such as diabetes by increasing the cellular usage of amino acids and consequently enhancing cardiovascular, cardiometabolic, and metabolic health [9][10][11][12][13].

2.2. Exercise Improves REDOX Balance and Chronic Inflammatory State

The underlying pathophysiological cause of numerous cardiovascular diseases is oxidative stress. Long-term exercise may improve the redox state of the body by boosting the antioxidant capacity, which is one of the most important processes through which exercise enhances cardiovascular health. During physical exercise, the contraction of skeletal muscle increases the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are primarily generated by the mitochondrial electron transfer pathway [14][15][16]. ROS might cause cellular oxidative stress and are a type of active hazardous material that causes biological macromolecular damage. The production of adequate ROS is physiologically necessary. ROS generated during exercise may stimulate mitochondrial synthesis, activate insulin signalling, stimulate protein synthesis and muscle development, control gene expression, and boost the body’s antioxidant capacity. Long-term exercise may improve mitochondrial function, the body’s antioxidant capacity, and the maintenance of its oxidative level [17]. Suppressing ROS generation during exercise reduces the health benefits of exercise [18]. Exercise may also improve mitochondrial dynamics by suppressing excessive mitochondrial division in cardiovascular disorders (ischaemic heart disease, heart failure) [19]. Acute exercise may have a similar “ischaemic preconditioning” effect on the heart by increasing the cardiac mitochondrial formation of ROS. Long-term physical activity may improve the mitochondrial antioxidant capacity and heart REDOX status [20][21]. Both aerobic exercise and resistance exercise substantially influence the homeostasis and function of mitochondria and are essential to the benefits of exercise on cardiovascular health.

Numerous chronic diseases, particularly metabolic cardiovascular disorders, throw the body into a state of low-grade chronic inflammation, which results in chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and represents a significant cause of chronic diseases and accelerated ageing. Long-term aerobic exercise was reported to decrease chronic inflammation and is an effective technique for interrupting this vicious cycle. Similarly, previous studies have shown that aerobic exercise may reduce the inflammatory marker high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hS-CRP) by 40% in coronary heart disease patients [22]. Additionally, exercise may boost the synthesis of interleukin-6 (IL-6) in human skeletal muscle and reduce the production of tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), and other proinflammatory molecules, and exercise thus serves as an anti-inflammatory input [23]. Furthermore, exercise may enhance fat metabolism, reduce visceral fat, and activate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and sympathetic nervous system to generate cortisol and other anti-inflammatory cytokines [24]. Long-term exercise has a systemic influence on the redox balance and inflammatory state of the body and may enhance cardiovascular health directly or indirectly.

2.3. Exercise Slows Ageing

The ageing process is associated with structural and functional body changes and is a risk factor for chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease. Long-term and consistent aerobic activity exerts an antiageing effect because it may encourage the migration of stem cells, resulting in a “youthful” body [25]. Exercise, for example, decreases the activation of glial cells due to ageing and increases the glial cell volume by increasing the levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). These growth factors boost the central nervous system’s insulin sensitivity and promote neurogenesis and angiogenesis. These activities may enhance cerebral blood flow, reduce amyloid deposition, and delay age-related neurodegenerative changes [26]. Exercise may also enhance the ageing-related endocrine function of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis and the muscular and bone condition of elderly individuals [27]. The effects of exercise on heart ageing include the following:

- ✓

-

Senile heart β adrenoceptor desensitization makes the heart less sensitive to adrenergic stimulation. Exercise can enhance the sensitivity of the myocardium to adrenergic stimulation and thus increases the cardiac functional reserve [28].

- ✓

-

The heart loses its Ca2+ processing capacity as it ages. The same stimulation reduces the intracellular Ca2+ increase and the cell contractility. Exercise can enhance intracellular Ca2+ processing capacity and cell contractility [29].

Mitochondrial dysfunction is an important mechanism for modulating cardiac function, in which exercise improves mitochondrial dynamics and function to adjust the cardiac metabolism, reduce oxidative stress, and increase the cardiac reserve capacity [30]. Moreover, vascular ageing is typically characterized by thickening and stiffening of large blood vessel walls, endothelial dysfunction, thrombosis-promoting changes in the vascular endothelium, proinflammatory and vasoconstrictive phenotype transformation, smooth muscle to secretory type changes, and reduced angiogenesis ability [31]. Long-term aerobic exercise can ease and even partly reverse the vascular ageing alterations listed above [32]. The fundamental mechanism through which exercise prevents ageing might be increasing the body’s antioxidant capacity and redox state because oxidative stress is a major cause of ageing.

2.4. Exercise Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension

Numerous scientific and clinical studies have shown that physical activity helps prevent and cure hypertension. Scientists have reported that all exercises (such as endurance, dynamic resistance, and isometric muscular strength training) reduce systolic blood pressure. Regular aerobic exercise may lower the resting blood pressure of hypertensive individuals by 57 mm Hg [33]. Similarly, high-intensity interval training and continuous aerobic training have similar effects on lowering blood pressure. Still, high-intensity interval training has tremendous potential for enhancing cardiopulmonary endurance, vascular endothelial function, and insulin sensitivity [34][35]. It is currently believed that the mechanism through which exercise prevents and improves hypertension consists primarily of the following:

- ✓

-

Reducing the resting systolic.

- ✓

-

Improving the oxidative stress levels and regulating the renin–angiotensin system to affect vascular remodelling and blood vessels.

- ✓

-

Increasing insulin sensitivity and nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability and promoting vasodilation and tissue perfusion.

2.5. Muscle-Building Effects of Exercise and Cardiovascular Health

Skeletal muscle represents approximately 40% of the human body’s mass, which makes it the most conspicuous organ. In addition to carrying out the body’s motor function, skeletal muscle is one of the major organs involved in glucose metabolism and, by extension, glucose homeostasis. A decrease in skeletal muscle mass may impair glucose metabolism and tolerance. In addition to enhancing insulin sensitivity, the muscle-building effect of exercise promotes glucose metabolism and tolerance by enhancing blood glucose “pathways” (into the skeletal muscle) that serve to buffer increases in blood glucose. Moreover, muscle is an essential endocrine organ of the body that can regulate cardiovascular metabolism and function via the production of various exercise factors. Recently, it has shown an association between the amount of human muscle tissue and the incidence and mortality of cardiovascular disease [36][37]. Muscular atrophy (e.g., sarcopenia) is characterized by a decrease in muscle-derived carnitine, which is essential for fatty acid transport in the heart and skeletal muscle and thus leads to abnormal fatty acid metabolism. Sarcopenia is common in patients with heart failure due to the retention of the ejection fraction, which may result in cardiovascular dysfunction due to abnormal glucose and lipid metabolism and decreased production of exercise hormones [38][39].

2.6. Other

In recent years, many studies have investigated the mechanism through which the biological function of gut bacteria can influence cardiovascular health via their metabolites. Indeed, the time it takes for physical exercise to affect intestinal flora is linked to higher body fat, higher triglycerides, and better circulation of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) and blood pressure. Intriguingly, the intestinal microbiota of top athletes and inactive individuals exhibit metagenomic and metabolomic differences, which shows that regular exercise might enhance metabolic health by improving the intestinal microbiota [40][41][42]. For instance, Liu et al. reported that exercise may boost short-chain fatty acids and decrease branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) levels by enhancing the gut flora and thus improve glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity [43]. Also, mental and psychological variables contribute to the onset and progression of ischaemic heart disease. Exercise may alleviate psychological stress, lower the moderate=to-severe anxiety prevalence in coronary heart disease patients by 56% to 69%, and facilitate cardiac rehabilitation [44]. In addition, physical activity may increase stem cell mobilization and tissue healing [45]. These interactions are principal contributors to cardiovascular health (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Exercise-induced cardiovascular benefits and underlying mechanisms: Exercise benefits cardiovascular health through its effects on the body. The primary mechanisms include enhancement of insulin sensitivity and metabolism in the cardiovascular system, reductions in oxidative stress and inflammation, the initiation of structural and functional remodelling in the cardiovascular system, the promotion of exerkine secretion from skeletal muscles and other tissues, and decreases in the risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

3. Exercise Improves the Cardiovascular Structure and Function

3.1. Remodeling of the Cardiovascular Structure and Function

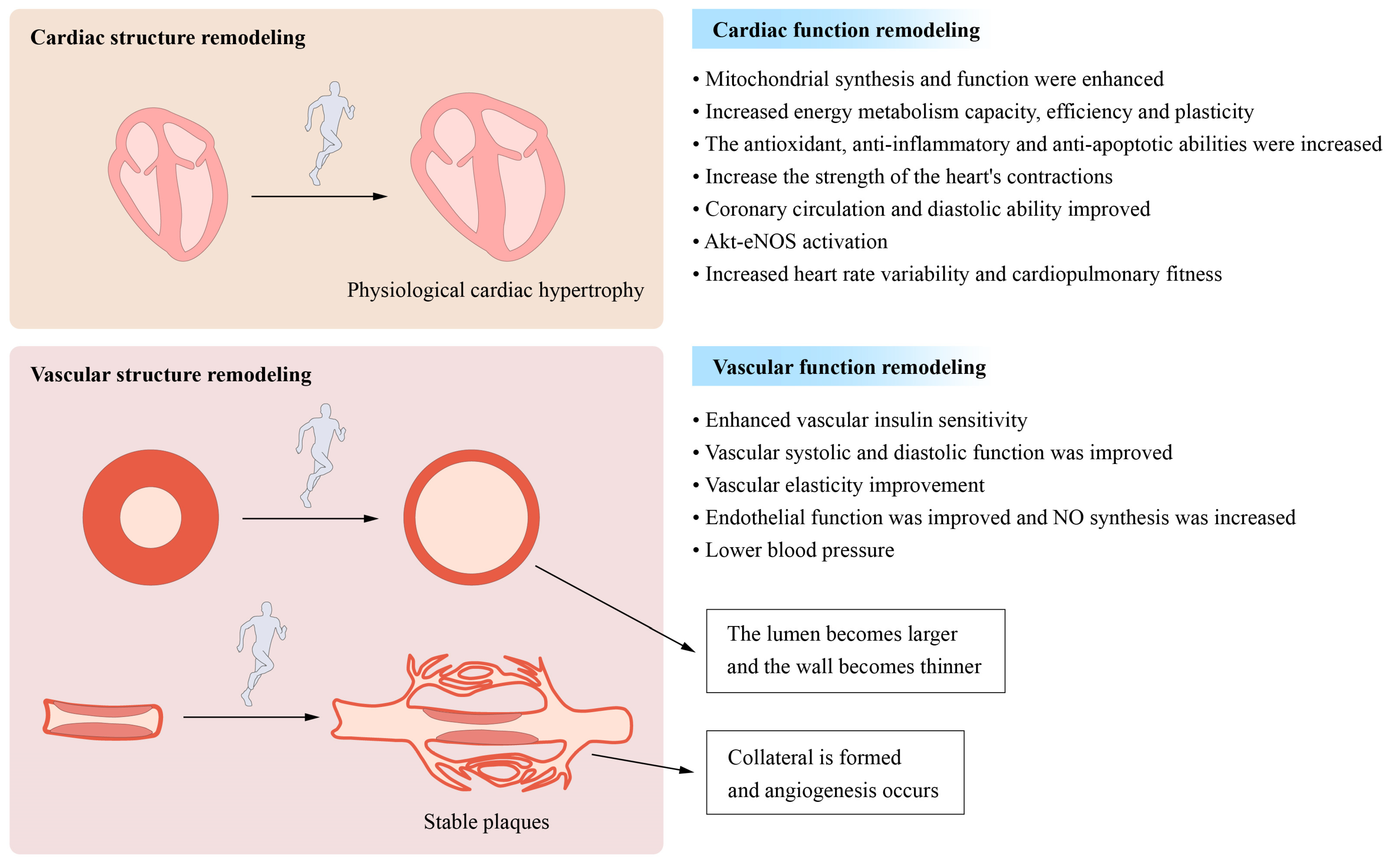

Even moderate exercise reduces pathological ventricular hypertrophy, such as that caused by heart failure, and improves cardiac shape and function under pathological conditions. Exercise-induced vascular remodelling is characterized by increases in the arterial vessel diameter and arterial vessel wall thickness (including coronary arteries) [46]. Likewise, exercise increases collagen and elastin content in atherosclerotic plaques while decreasing atherosclerosis-related adverse outcomes [47]. This effect may be one of the mechanisms through which physical activity protects vital organ function and retards ageing [48].

Exercise impacts blood vessels and increases the development of new blood vessels. Exercise, may increase the capillary formation and promote angiogenesis, while it may widen the arterial lumen through a process known as arteriogenesis (Figure 3). This process may occur in existing blood vessels (including coronary arteries) and thus demonstrates substantial vascular system adaptability. A key regulator of angiogenesis is the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), whose expression in skeletal and cardiac muscle may be increased by exercise [49][50].

Figure 3. Long-term moderate- and high-intensity exercise induces cardiovascular remodelling: Moderate- and high-intensity exercise performed over a prolonged period both causes and promotes structural and functional remodelling in the cardiovascular system. The structural remodeling process involves physiological cardiac hypertrophy, a decrease in the vascular wall thickness, and increases in the luminal width of conduit arteries. The process of functional remodelling is characterized by increases in cardiac contraction and dilatation and reductions in the heart rate and blood pressure.

Conversely, in atherosclerosis, exercise may enhance the amount of circulating endostatin and angiogenesis in plaque tissue, thus preventing the progression of atherosclerotic plaque, which may have important implications for the prevention and treatment of coronary heart disease [51]. However, certain circumstances are required for angiogenesis and arteriogenesis to maintain tissue perfusion. The disturbance of these systems is one of the pathogenic mechanisms underlying several diseases, such as coronary heart disease. Angiogenesis and arteriogenesis may boost coronary collateral circulation, reduce myocardial damage during myocardial infarction, and improve blood perfusion and tissue healing [52]. Exercise may stimulate the ischaemic myocardium, and angiogenesis and arteriogenesis can increase coronary collateral circulation and improve blood vessel and tissue healing perfusion. Endothelial dysfunction is one of the pathogenic mechanisms contributing to the development and progression of certain cardiovascular diseases. Physical activity may improve vascular endothelial function through mechanisms independent of cholesterol, blood pressure, glucose tolerance, and body weight [53].

The effect of exercise on cardiovascular health is partially attributable to its direct mechanical stimulation of the cardiovascular system. One of the primary variables of cardiovascular function is mechanical force. For example, exercise-induced acceleration of the tissue blood flow increases shear forces, stimulating nitric oxide generation by vascular endothelial cells, widening capillaries, and improving blood perfusion to tissues and organs [54]. Similarly, shear stress-induced movement increases blood flow and can directly induce vascular endothelial cells to secrete a movement factor. The latter, which is absorbed by heart muscle cells from outside the blood circulation and plays a role in cardiac protection, promotes interactions between the heart and blood vessels to affect cardiovascular regulation and protection [55]. In a recent population-controlled study, stretching was found to be more effective for lowering blood pressure than brisk walking. The process may be related to the enhancement of vascular stiffness by mechanical stretching stimulation [56].

The mechanism through which mechanical force stimulates and garners a response in the cardiovascular system remains unknown. Piezo receptors on the cell membranes of vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and other tissues may sense mechanical force stimulation and initiate cellular calcium influx, resulting in changes in cellular functional activities. These receptors regulate cardiovascular function in response to exercise and are linked to the initiation and progression of cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, heart failure, and hypertension [57][58].

3.2. Improvements in Myocardial Mitochondrial Function and Metabolism

Numerous studies have shown that increased mitochondrial activity is directly connected to the cardioprotective benefits of exercise. Mitochondria govern metabolic, redox, and cell fate processes. The myocardium is the most mitochondrially dense tissue in the body, accounts for approximately 40% of the volume of cardiomyocytes, and serves as the heart’s main energy source. During exercise, the energy demands of the heart increase substantially, leading to an increase in ATP generation. In addition, the heart has access to almost all metabolic substrates. Under normal conditions, the major metabolic substrate of the heart is lipoic acid (40–70%). During exercise, the myocardium increases its use of fatty acids and lactic acid while decreasing its glucose usage. Prolonged exercise increases myocardial glucose use, particularly the glycolysis level, which is related to the establishment and progression of cardiac physiological hypertrophy [59][60]. Under normal conditions, the major metabolic substrate of the heart is lipoic acid (40–70%). During exercise, the myocardium increases its use of fatty acids and lactic acid while decreasing its glucose usage. Prolonged exercise increases myocardial glucose use, especially the glycolysis level, which is related to the establishment and progression of cardiac physiological hypertrophy [61][62]. Long-term exercise may increase mitochondrial dynamics and function and thus increases the pace and efficiency of cardiac metabolism and the adaptability of the metabolic switch and strengthen myocardial damage resistance [63]. Exercise increases the transcription factors PGC-1, PPAR, NRF2, and others that govern cell function and mitochondrial homeostasis [64].

3.3. Other

In addition to the abovementioned mechanisms, exercise influences cardiovascular function. For example, prolonged hyperexcitation of sympathetic neurons has a negative impact on the structure and function of the cardiovascular system, which is one of the causes of several cardiovascular diseases [65]. Long-term aerobic exercise may enhance cardiovascular autonomic nervous system function and homeostasis, increase parasympathetic nerve activity, decrease sympathetic nervous activity, increase heart rate variability (HRV), thereby exerting a cardioprotective effect. Cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) reduction due to ageing or long-term inactivity is also connected to the onset and development of cardiovascular diseases. According to a meta-analysis, all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality are lowered by 13 and 15%, respectively, for each additional metabolic equivalent (MET) of cardiopulmonary fitness [66][67]. Aerobic and resistance exercise may improve both cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiovascular health.

References

- Lavie, C.J.; Ozemek, C.; Carbone, S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Blair, S.N. Sedentary Behavior, Exercise, and Cardiovascular Health. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 799–815.

- Kramer, A. An Overview of the Beneficial Effects of Exercise on Health and Performance. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1228, 3–22.

- Coats, A.J.S.; Forman, D.E.; Haykowsky, M.; Kitzman, D.W.; McNeil, A.; Campbell, T.S.; Arena, R. Physical function and exercise training in older patients with heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 550–559.

- Zhang, G.L.; Sun, M.L.; Zhang, X.A. Exercise-Induced Adult Cardiomyocyte Proliferation in Mammals. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 729364.

- Wang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Zang, W.; Jiang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, S. Exercise training reduces insulin resistance in postmyocardial infarction rats. Physiol. Rep. 2015, 3, e12339.

- Jia, D.; Hou, L.; Lv, Y.; Xi, L.; Tian, Z. Postinfarction exercise training alleviates cardiac dysfunction and adverse remodeling via mitochondrial biogenesis and SIRT1/PGC-1alpha/PI3K/Akt signaling. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 23705–23718.

- Neri Serneri, G.G.; Boddi, M.; Modesti, P.A.; Cecioni, I.; Coppo, M.; Padeletti, L.; Michelucci, A.; Colella, A.; Galanti, G. Increased cardiac sympathetic activity and insulin-like growth factor-I formation are associated with physiological hypertrophy in athletes. Circ. Res. 2001, 89, 977–982.

- Lavie, C.J.; Arena, R.; Swift, D.L.; Johannsen, N.M.; Sui, X.; Lee, D.C.; Earnest, C.P.; Church, T.S.; O’Keefe, J.H.; Milani, R.V.; et al. Exercise and the cardiovascular system: Clinical science and cardiovascular outcomes. Circ. Res. 2015, 117, 207–219.

- Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Fan, L.; Booz, G.W.; Roman, R.J.; Chen, Z.; Fan, F. Accelerated cerebral vascular injury in diabetes is associated with vascular smooth muscle cell dysfunction. Geroscience 2020, 42, 547–561.

- Short, K.R.; Chadwick, J.Q.; Teague, A.M.; Tullier, M.A.; Wolbert, L.; Coleman, C.; Copeland, K.C. Effect of Obesity and Exercise Training on Plasma Amino Acids and Amino Metabolites in American Indian Adolescents. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 3249–3261.

- Umpierre, D.; Ribeiro, P.A.; Kramer, C.K.; Leitao, C.B.; Zucatti, A.T.; Azevedo, M.J.; Gross, J.L.; Ribeiro, J.P.; Schaan, B.D. Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2011, 305, 1790–1799.

- Li, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Yan, W.; Gao, E.; Cheng, H.; Wu, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; et al. Branched chain amino acids exacerbate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion vulnerability via enhancing GCN2/ATF6/PPAR-alpha pathway-dependent fatty acid oxidation. Theranostics 2020, 10, 5623–5640.

- Murthy, V.L.; Yu, B.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Alkis, T.; Pico, A.R.; Yeri, A.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Bressler, J.; Ballantyne, C.M.; et al. Molecular Signature of Multisystem Cardiometabolic Stress and Its Association with Prognosis. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 1144–1153.

- Shaw, E.; Leung, G.K.W.; Jong, J.; Coates, A.M.; Davis, R.; Blair, M.; Huggins, C.E.; Dorrian, J.; Banks, S.; Kellow, N.J.; et al. The Impact of Time of Day on Energy Expenditure: Implications for Long-Term Energy Balance. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2383.

- Powers, S.K.; Deminice, R.; Ozdemir, M.; Yoshihara, T.; Bomkamp, M.P.; Hyatt, H. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: Friend or foe? J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 415–425.

- Jackson, M.J. Control of reactive oxygen species production in contracting skeletal muscle. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 2477–2486.

- Taherkhani, S.; Suzuki, K.; Castell, L. A Short Overview of Changes in Inflammatory Cytokines and Oxidative Stress in Response to Physical Activity and Antioxidant Supplementation. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 886.

- Ristow, M.; Zarse, K.; Oberbach, A.; Kloting, N.; Birringer, M.; Kiehntopf, M.; Stumvoll, M.; Kahn, C.R.; Bluher, M. Antioxidants prevent health-promoting effects of physical exercise in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 8665–8670.

- Ghahremani, R.; Damirchi, A.; Salehi, I.; Komaki, A.; Esposito, F. Mitochondrial dynamics as an underlying mechanism involved in aerobic exercise training-induced cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Life Sci. 2018, 213, 102–108.

- Powers, S.K.; Sollanek, K.J.; Wiggs, M.P.; Demirel, H.A.; Smuder, A.J. Exercise-induced improvements in myocardial antioxidant capacity: The antioxidant players and cardioprotection. Free Radic. Res. 2014, 48, 43–51.

- Done, A.J.; Traustadottir, T. Nrf2 mediates redox adaptations to exercise. Redox Biol. 2016, 10, 191–199.

- Milani, R.V.; Lavie, C.J.; Mehra, M.R. Reduction in C-reactive protein through cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 43, 1056–1061.

- Starkie, R.; Ostrowski, S.R.; Jauffred, S.; Febbraio, M.; Pedersen, B.K. Exercise and IL-6 infusion inhibit endotoxin-induced TNF-alpha production in humans. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 884–886.

- Mathur, N.; Pedersen, B.K. Exercise as a mean to control low-grade systemic inflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2008, 2008, 109502.

- Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B.; Rysz-Gorzynska, M.; Gluba-Brzozka, A. Ageing, Age-Related Cardiovascular Risk and the Beneficial Role of Natural Components Intake. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 183.

- Szalewska, D.; Radkowski, M.; Demkow, U.; Winklewski, P.J. Exercise Strategies to Counteract Brain Aging Effects. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1020, 69–79.

- Janssen, J.A. Impact of Physical Exercise on Endocrine Aging. Front. Horm. Res. 2016, 47, 68–81.

- Leosco, D.; Parisi, V.; Femminella, G.D.; Formisano, R.; Petraglia, L.; Allocca, E.; Bonaduce, D. Effects of exercise training on cardiovascular adrenergic system. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 348.

- Baekkerud, F.H.; Salerno, S.; Ceriotti, P.; Morland, C.; Storm-Mathisen, J.; Bergersen, L.H.; Hoydal, M.A.; Catalucci, D.; Stolen, T.O. High Intensity Interval Training Ameliorates Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Left Ventricle of Mice with Type 2 Diabetes. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2019, 19, 422–431.

- Roh, J.; Rhee, J.; Chaudhari, V.; Rosenzweig, A. The Role of Exercise in Cardiac Aging: From Physiology to Molecular Mechanisms. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 279–295.

- Gliemann, L.; Nyberg, M.; Hellsten, Y. Effects of exercise training and resveratrol on vascular health in aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 98, 165–176.

- Radak, Z.; Torma, F.; Berkes, I.; Goto, S.; Mimura, T.; Posa, A.; Balogh, L.; Boldogh, I.; Suzuki, K.; Higuchi, M.; et al. Exercise effects on physiological function during aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 132, 33–41.

- Naci, H.; Salcher-Konrad, M.; Dias, S.; Blum, M.R.; Sahoo, S.A.; Nunan, D.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. How does exercise treatment compare with antihypertensive medications? A network meta-analysis of 391 randomised controlled trials assessing exercise and medication effects on systolic blood pressure. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 859–869.

- Costa, E.C.; Hay, J.L.; Kehler, D.S.; Boreskie, K.F.; Arora, R.C.; Umpierre, D.; Szwajcer, A.; Duhamel, T.A. Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training Versus Moderate-Intensity Continuous Training on Blood Pressure in Adults with Pre- to Established Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 2127–2142.

- Ciolac, E.G.; Bocchi, E.A.; Bortolotto, L.A.; Carvalho, V.O.; Greve, J.M.; Guimaraes, G.V. Effects of high-intensity aerobic interval training vs. moderate exercise on hemodynamic, metabolic and neuro-humoral abnormalities of young normotensive women at high familial risk for hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 2010, 33, 836–843.

- Feraco, A.; Gorini, S.; Armani, A.; Camajani, E.; Rizzo, M.; Caprio, M. Exploring the Role of Skeletal Muscle in Insulin Resistance: Lessons from Cultured Cells to Animal Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9327.

- Powers, S.K.; Morton, A.B.; Ahn, B.; Smuder, A.J. Redox control of skeletal muscle atrophy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 98, 208–217.

- Kokkinidis, D.G.; Arfaras-Melainis, A.; Giannakoulas, G. Sarcopenia in heart failure: ‘waste’ the appropriate time and resources, not the muscles. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 1019–1021.

- Konishi, M.; Kagiyama, N.; Kamiya, K.; Saito, H.; Saito, K.; Ogasahara, Y.; Maekawa, E.; Misumi, T.; Kitai, T.; Iwata, K.; et al. Impact of sarcopenia on prognosis in patients with heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 1022–1029.

- Son, J.; Jang, L.G.; Kim, B.Y.; Lee, S.; Park, H. The Effect of Athletes’ Probiotic Intake May Depend on Protein and Dietary Fiber Intake. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2947.

- Allen, J.M.; Mailing, L.J.; Niemiro, G.M.; Moore, R.; Cook, M.D.; White, B.A.; Holscher, H.D.; Woods, J.A. Exercise Alters Gut Microbiota Composition and Function in Lean and Obese Humans. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 747–757.

- Barton, W.; Penney, N.C.; Cronin, O.; Garcia-Perez, I.; Molloy, M.G.; Holmes, E.; Shanahan, F.; Cotter, P.D.; O’Sullivan, O. The microbiome of professional athletes differs from that of more sedentary subjects in composition and particularly at the functional metabolic level. Gut 2018, 67, 625–633.

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ni, Y.; Cheung, C.K.Y.; Lam, K.S.L.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Z.; Ye, D.; Guo, J.; Tse, M.A.; et al. Gut Microbiome Fermentation Determines the Efficacy of Exercise for Diabetes Prevention. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 77–91.e5.

- Lavie, C.J.; Milani, R.V. Prevalence of anxiety in coronary patients with improvement following cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training. Am. J. Cardiol. 2004, 93, 336–339.

- Hambrecht, R.; Walther, C.; Mobius-Winkler, S.; Gielen, S.; Linke, A.; Conradi, K.; Erbs, S.; Kluge, R.; Kendziorra, K.; Sabri, O.; et al. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty compared with exercise training in patients with stable coronary artery disease: A randomized trial. Circulation 2004, 109, 1371–1378.

- Thijssen, D.H.; Cable, N.T.; Green, D.J. Impact of exercise training on arterial wall thickness in humans. Clin. Sci. 2012, 122, 311–322.

- Shimada, K.; Mikami, Y.; Murayama, T.; Yokode, M.; Fujita, M.; Kita, T.; Kishimoto, C. Atherosclerotic plaques induced by marble-burying behavior are stabilized by exercise training in experimental atherosclerosis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2011, 151, 284–289.

- Seals, D.R.; Desouza, C.A.; Donato, A.J.; Tanaka, H. Habitual exercise and arterial aging. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 105, 1323–1332.

- Schuttler, D.; Clauss, S.; Weckbach, L.T.; Brunner, S. Molecular Mechanisms of Cardiac Remodeling and Regeneration in Physical Exercise. Cells 2019, 8, 1128.

- Golbidi, S.; Laher, I. Molecular mechanisms in exercise-induced cardioprotection. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2011, 2011, 972807.

- Gu, J.W.; Gadonski, G.; Wang, J.; Makey, I.; Adair, T.H. Exercise increases endostatin in circulation of healthy volunteers. BMC Physiol. 2004, 4, 2.

- Heaps, C.L.; Robles, J.C.; Sarin, V.; Mattox, M.L.; Parker, J.L. Exercise training-induced adaptations in mediators of sustained endothelium-dependent coronary artery relaxation in a porcine model of ischemic heart disease. Microcirculation 2014, 21, 388–400.

- Green, D.J.; O’Driscoll, G.; Joyner, M.J.; Cable, N.T. Exercise and cardiovascular risk reduction: Time to update the rationale for exercise? J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 105, 766–768.

- Hambrecht, R.; Adams, V.; Erbs, S.; Linke, A.; Krankel, N.; Shu, Y.; Baither, Y.; Gielen, S.; Thiele, H.; Gummert, J.F.; et al. Regular physical activity improves endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease by increasing phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation 2003, 107, 3152–3158.

- Hou, Z.; Qin, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, G.; Wu, J.; Li, J.; Sha, J.; Chen, J.; Xia, J.; et al. Longterm Exercise-Derived Exosomal miR-342-5p: A Novel Exerkine for Cardioprotection. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1386–1400.

- Ko, J.; Deprez, D.; Shaw, K.; Alcorn, J.; Hadjistavropoulos, T.; Tomczak, C.; Foulds, H.; Chilibeck, P.D. Stretching is Superior to Brisk Walking for Reducing Blood Pressure in People with High-Normal Blood Pressure or Stage I Hypertension. J. Phys. Act. Health 2021, 18, 21–28.

- Beech, D.J.; Kalli, A.C. Force Sensing by Piezo Channels in Cardiovascular Health and Disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 2228–2239.

- Shah, V.; Patel, S.; Shah, J. Emerging role of Piezo ion channels in cardiovascular development. Dev. Dyn. 2022, 251, 276–286.

- Golbidi, S.; Laher, I. Exercise and the cardiovascular system. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 210852.

- Young, C.G.; Knight, C.A.; Vickers, K.C.; Westbrook, D.; Madamanchi, N.R.; Runge, M.S.; Ischiropoulos, H.; Ballinger, S.W. Differential effects of exercise on aortic mitochondria. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 288, H1683–H1689.

- Fulghum, K.; Hill, B.G. Metabolic Mechanisms of Exercise-Induced Cardiac Remodeling. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 127.

- Gibb, A.A.; Epstein, P.N.; Uchida, S.; Zheng, Y.; McNally, L.A.; Obal, D.; Katragadda, K.; Trainor, P.; Conklin, D.J.; Brittian, K.R.; et al. Exercise-Induced Changes in Glucose Metabolism Promote Physiological Cardiac Growth. Circulation 2017, 136, 2144–2157.

- Lee, Y.; Min, K.; Talbert, E.E.; Kavazis, A.N.; Smuder, A.J.; Willis, W.T.; Powers, S.K. Exercise protects cardiac mitochondria against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2012, 44, 397–405.

- Boulghobra, D.; Coste, F.; Geny, B.; Reboul, C. Exercise training protects the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury: A central role for mitochondria? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 152, 395–410.

- Seals, D.R.; Dinenno, F.A. Collateral damage: Cardiovascular consequences of chronic sympathetic activation with human aging. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004, 287, H1895–H1905.

- DeFina, L.F.; Haskell, W.L.; Willis, B.L.; Barlow, C.E.; Finley, C.E.; Levine, B.D.; Cooper, K.H. Physical activity versus cardiorespiratory fitness: Two (partly) distinct components of cardiovascular health? Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 57, 324–329.

- Myers, J.; McAuley, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Despres, J.P.; Arena, R.; Kokkinos, P. Physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness as major markers of cardiovascular risk: Their independent and interwoven importance to health status. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 57, 306–314.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cell Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Entry Collection:

Hypertension and Cardiovascular Diseases

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

05 Jan 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No