| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vania Paschoalin | -- | 4290 | 2022-12-23 00:20:12 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 4290 | 2022-12-23 03:02:46 | | |

Video Upload Options

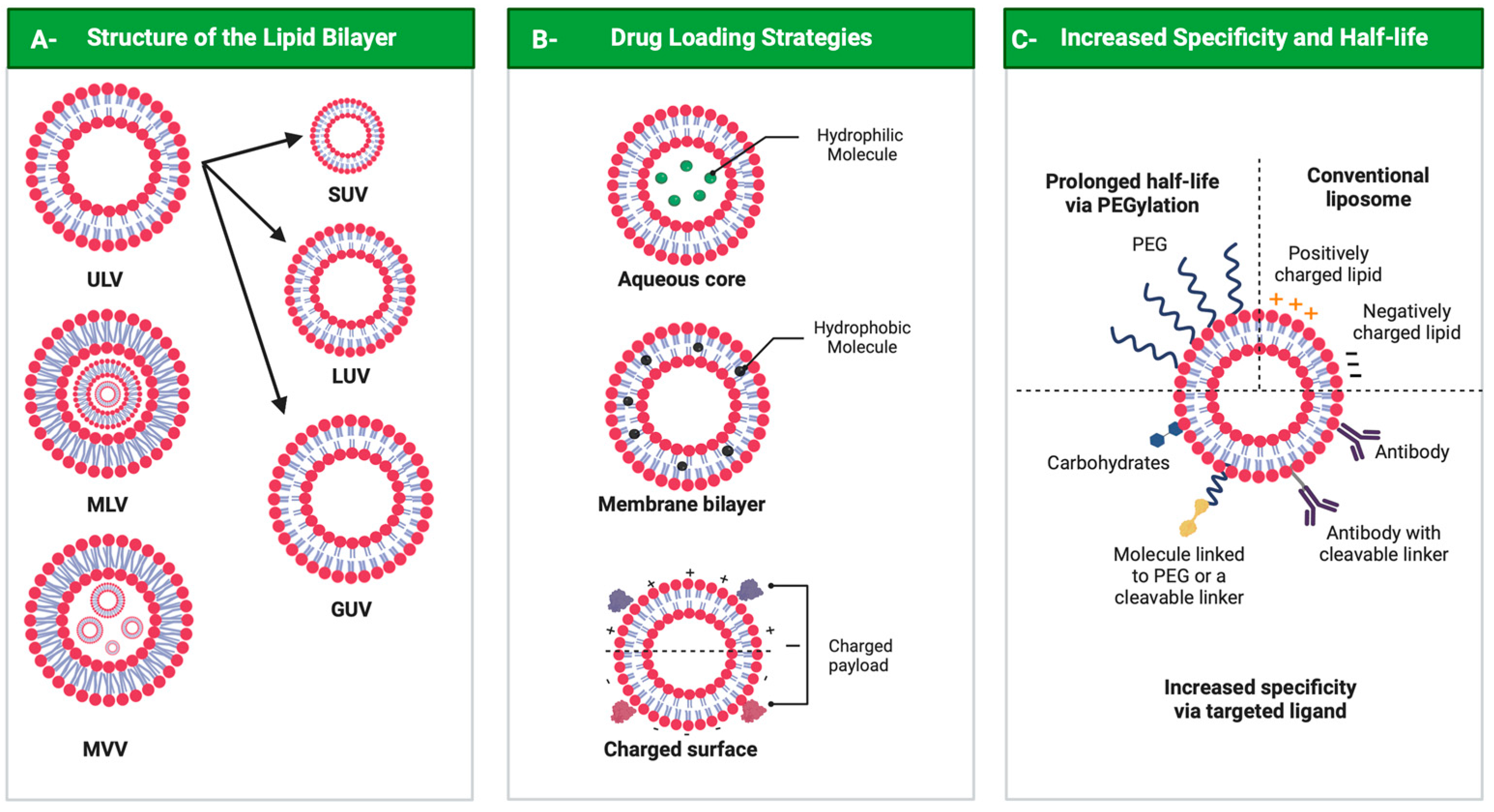

Drug delivery systems are believed to increase pharmaceutical efficacy and the therapeutic index by protecting and stabilizing bioactive molecules, such as protein and peptides, against body fluids’ enzymes and/or unsuitable physicochemical conditions while preserving the surrounding healthy tissues from toxicity. Liposomes are biocompatible and biodegradable and do not cause immunogenicity following intravenous or topical administration. Still, their most important characteristic is the ability to load any drug or complex molecule uncommitted to its hydrophobic or hydrophilic character. Selecting lipid components, ratios and thermo-sensitivity is critical to achieve a suitable nano-liposomal formulation. Nano-liposomal surfaces can be tailored to interact successfully with target cells, avoiding undesirable associations with plasma proteins and enhancing their half-life in the bloodstream. Macropinocytosis-dynamin-independent, cell-membrane-cholesterol-dependent processes, clathrin, and caveolae-independent mechanisms are involved in liposome internalization and trafficking within target cells to deliver the loaded drugs to modulate cell function.

1. A General Overview of the Remarkable Role of Nature in Providing Potential Pharmacological Compounds

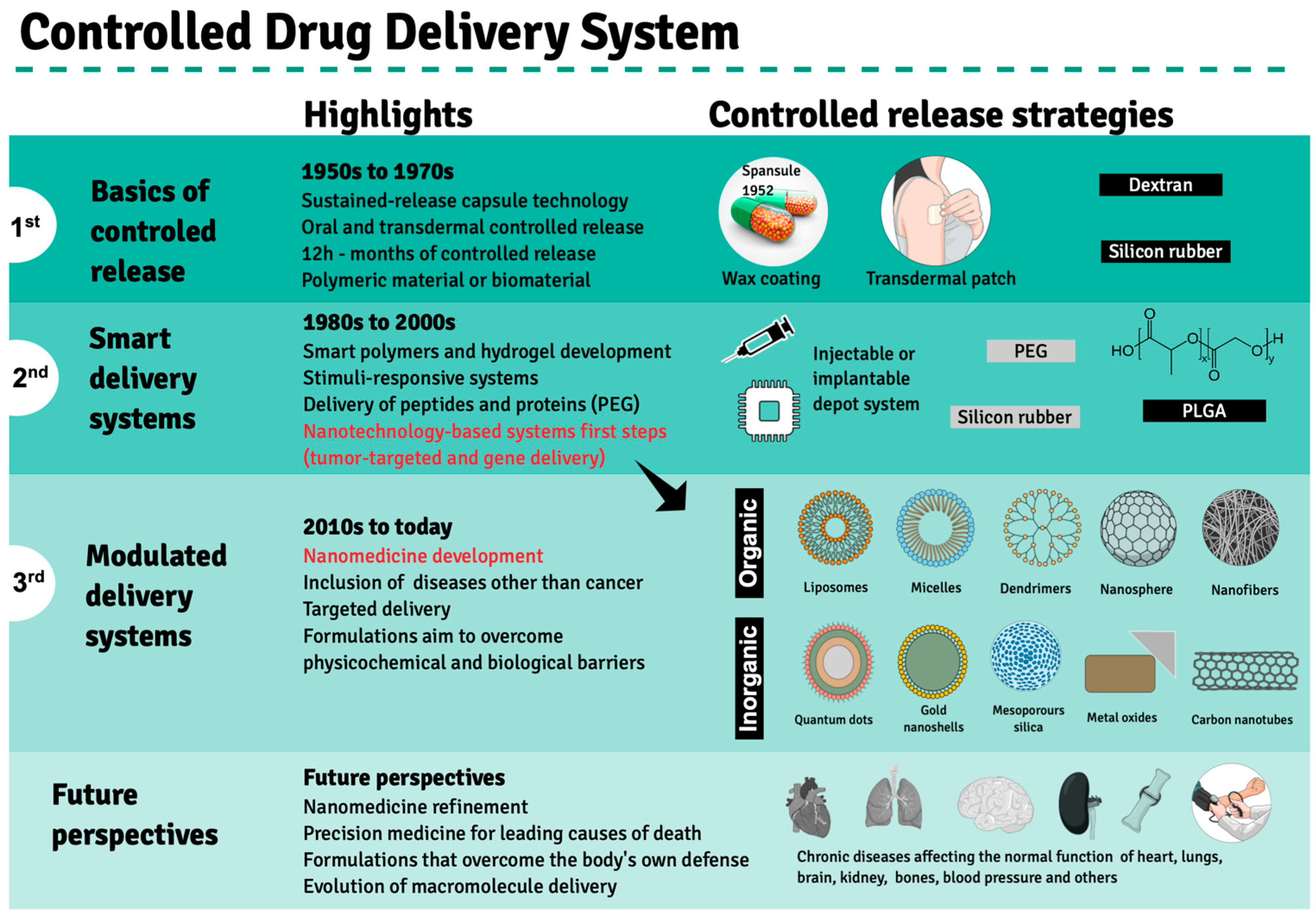

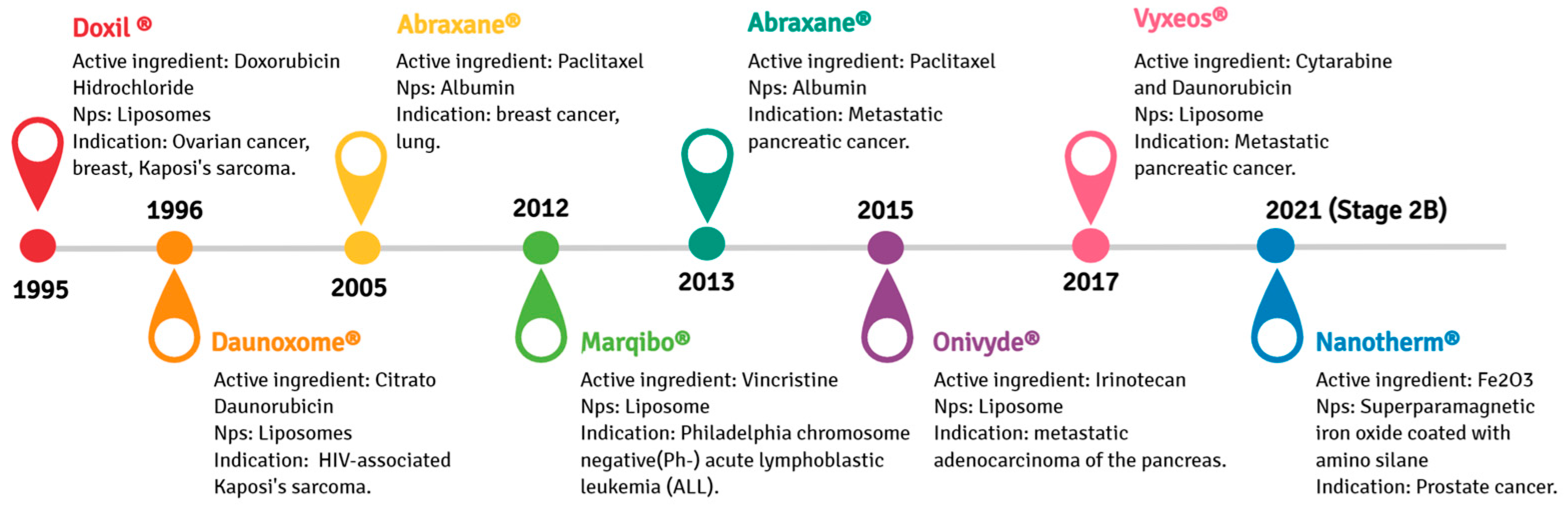

2. Evolution of Drug Delivery Systems and the Emergence of Nanotechnology in Clinical Treatments

|

Nano-Delivery System |

Therapeutic Agent |

Loading Mechanism |

Pathology |

Biological Assay |

Pharmacological Response |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) |

Tocotrienol/ Simvastatin |

Core co-encapsulation |

Mammary adenocarcinoma |

In vitro (+SA lineage) |

Improved anti-proliferative TRF and SIM effect upon encapsulation |

[36] |

|

Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) |

Linalool |

Encapsulation |

Hepatocarcinoma Lung adenocarcinoma |

In vitro (HepG2 and A549 cell lineages) |

Improved cytotoxic effect on human lung- and liver-derived tumor cells (A549 and HepG2) at > 1.0 mM in a dose/time-dependent manner |

[37] |

|

Lipid nano-capsules |

Simvastatin |

Encapsulation |

Breast carcinoma |

In vitro (MCF-7 lineage) |

Increased cytotoxicity at IC50 = 1.4 ± 0.02 mg/mL |

[38] |

|

Folic acid-chitosan |

Vincristine |

Encapsulation |

Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) |

In vitro (NCI-H460 lineage) |

Anticancer activity at a 4:25 formulation against non-small-cell lung cancer (NCI-H460). |

[39] |

|

Liposomes |

(III) complexes |

Encapsulation |

Several types of cancer |

In vitro (HepG2; HTC-116; HeLa; A549; BEL-7402; SGC-7901; Eca-109; B-16 and human liver cell L02) In vivo (mice) |

Ir-1-Lipo and Ir-2-Lipo induced apoptosis at 55.6% and 69.3% levels. Improved anticancer activity against A549 cells; Ir-2-Lipo effectively inhibited tumor growth in a murine model |

[40] |

|

PGS-coated cationic liposomes with Bcl-2 siRNA-corona |

Doxorubicin (Dox) |

Electrostatic adsorption |

Hepatocellular carcinoma |

In vitro (Bel7402 sensitive cells and Bel7402/5-FU MDR cells) In vivo (mice) |

7-fold improved anticancer effect by apoptosis induction and tumor growth inhibition compared to free Dox |

[41] |

|

Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) nanofibers (NFs) |

Metformin |

Encapsulation |

Lung adenocarcinoma |

In vitro (A549 cell lineage) |

Significant cytotoxicity against A549 cells by apoptosis induction |

[42] |

|

Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers |

Methotrexate (MTX) and D-glucose (GLU) |

Encapsulation |

Breast cancer |

In vitro (MDA MB-231 lineage |

OS-PAMAM-MTX-GLU displaying higher anticancer potential compared to free MTX after a 4 h exposure without significantly affecting healthy human HaCat cells |

[43] |

|

Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers |

Liver-x-receptor (LXR) |

Specific receptor binding |

Atherosclerosis |

In vitro (mouse peritoneal macrophages) In vivo (mice) |

mDNP-LXR-L-mediated delivery reduced in the expression of metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9); followed by plaque size reduction and decreased necrosis |

[44] |

|

Gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) |

N-isobutyryl-L-cysteine (L-NIBC) |

Au-S bond |

Parkinson’s disease |

In vitro (PC12 and SH-SY5Y lineages) In vivo (mice) |

AuNCs exhibited superior neuroprotective effects in 1-metil-4-phenilyridine (MPP+) lesioned cell and 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridine (MPTP) induced mouse PD models |

[45] |

3. Liposomal Formulation Performance: Characteristics, Functionalization and Internalization

References

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Supuran, C.T. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216.

- Süntar, I. Importance of ethnopharmacological studies in drug discovery: Role of medicinal plants. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 1199–1209.

- Rask-Andersen, M.; Masuram, S.; Schiöth, H.B. The Druggable Genome: Evaluation of Drug Targets in Clinical Trials Suggests Major Shifts in Molecular Class and Indication. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 54, 9–26.

- Vargason, A.M.; Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. The evolution of commercial drug delivery technologies. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 951–967.

- Bernardini, S.; Tiezzi, A.; Laghezza Masci, V.; Ovidi, E. Natural products for human health: An historical overview of the drug discovery approaches. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 1926–1950.

- Patridge, E.; Gareiss, P.; Kinch, M.S.; Hoyer, D. An analysis of FDA-approved drugs: Natural products and their derivatives. Drug Discov. Today 2016, 21, 204–207.

- Wright, G.D. Unlocking the potential of natural products in drug discovery. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 55–57.

- Shen, B. A New Golden Age of Natural Products Drug Discovery. Cell 2015, 163, 1297–1300.

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803.

- Park, H.; Otte, A.; Park, K. Evolution of drug delivery systems: From 1950 to 2020 and beyond. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2022, 342, 53–65.

- Santos, D.I.; Saraiva, J.M.A.; Vicente, A.A.; Moldão-Martins, M. Methods for determining bioavailability and bioaccessibility of bioactive compounds and nutrients. In Innovative Thermal and Non-Thermal Processing, Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 23–54.

- Baranowska, M.; Suliborska, K.; Todorovic, V.; Kusznierewicz, B.; Chrzanowski, W.; Sobajic, S.; Bartoszek, A. Interactions between bioactive components determine antioxidant, cytotoxic and nutrigenomic activity of cocoa powder extract. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 154, 48–61.

- Ren, B.; Kwah, M.X.-Y.; Liu, C.; Ma, Z.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Ding, L.; Xiang, X.; Ho, P.C.-L.; Wang, L.; Ong, P.S. Resveratrol for cancer therapy: Challenges and future perspectives. Cancer Lett. 2021, 515, 63–72.

- Wen, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Bi, H.; Yang, B. Structure identification of soybean peptides and their immunomodulatory activity. Food Chem. 2021, 359, 129970.

- Moreno-Valdespino, C.A.; Luna-Vital, D.; Camacho-Ruiz, R.M.; Mojica, L. Bioactive proteins and phytochemicals from legumes: Mechanisms of action preventing obesity and type-2 diabetes. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108905.

- Wu, S.-J.; Tung, Y.-J.; Ng, L.-T. Anti-diabetic effects of Grifola frondosa bioactive compound and its related molecular signaling pathways in palmitate-induced C2C12 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 260, 112962.

- Bhushan, I.; Sharma, M.; Mehta, M.; Badyal, S.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, I.; Singh, H.; Sistla, S. Bioactive compounds and probiotics–a ray of hope in COVID-19 management. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2021, 10, 131–140.

- Siu, F.Y.; Ye, S.; Lin, H.; Li, S. Galactosylated PLGA nanoparticles for the oral delivery of resveratrol: Enhanced bioavailability and in vitro anti-inflammatory activity. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 4133.

- Wu, Y.; Cui, J. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate provides neuroprotection via AMPK activation against traumatic brain injury in a mouse model. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2020, 393, 2209–2220.

- Reza Rezaie, H.; Esnaashary, M.; Aref arjmand, A.; Öchsner, A. The History of Drug Delivery Systems. In A Review of Biomaterials and Their Applications in Drug Delivery; Reza Rezaie, H., Esnaashary, M., Aref arjmand, A., Öchsner, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 1–8.

- Dai Phung, C.; Tran, T.H.; Nguyen, H.T.; Jeong, J.-H.; Yong, C.S.; Kim, J.O. Current developments in nanotechnology for improved cancer treatment, focusing on tumor hypoxia. J. Control. Release 2020, 324, 413–429.

- Barani, M.; Bilal, M.; Sabir, F.; Rahdar, A.; Kyzas, G.Z. Nanotechnology in ovarian cancer: Diagnosis and treatment. Life Sci. 2021, 266, 118914.

- Sarmah, D.; Banerjee, M.; Datta, A.; Kalia, K.; Dhar, S.; Yavagal, D.R.; Bhattacharya, P. Nanotechnology in the diagnosis and treatment of stroke. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 585–592.

- Schlichtmann, B.W.; Hepker, M.; Palanisamy, B.N.; John, M.; Anantharam, V.; Kanthasamy, A.G.; Narasimhan, B.; Mallapragada, S.K. Nanotechnology-mediated therapeutic strategies against synucleinopathies in neurodegenerative disease. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2021, 31, 100673.

- Bhavana, V.; Thakor, P.; Singh, S.B.; Mehra, N.K. COVID-19: Pathophysiology, treatment options, nanotechnology approaches, and research agenda to combating the SARS-CoV2 pandemic. Life Sci. 2020, 261, 118336.

- Anand, K.; Vadivalagan, C.; Joseph, J.S.; Singh, S.K.; Gulati, M.; Shahbaaz, M.; Abdellattif, M.H.; Prasher, P.; Gupta, G.; Chellappan, D.K. A novel nano therapeutic using convalescent plasma derived exosomal (CPExo) for COVID-19: A combined hyperactive immune modulation and diagnostics. Chem. -Biol. Interact. 2021, 344, 109497.

- Misra, R.; Acharya, S.; Sahoo, S.K. Cancer nanotechnology: Application of nanotechnology in cancer therapy. Drug Discov. Today 2010, 15, 842–850.

- McNeil, S.E. Unique benefits of nanotechnology to drug delivery and diagnostics. In Characterization of Nanoparticles Intended for Drug Delivery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 3–8.

- Petros, R.A.; DeSimone, J.M. Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 615–627.

- Boulaiz, H.; Alvarez, P.J.; Ramirez, A.; Marchal, J.A.; Prados, J.; Rodriguez-Serrano, F.; Peran, M.; Melguizo, C.; Aranega, A. Nanomedicine: Application areas and development prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 3303–3321.

- Ferrari, M. Cancer nanotechnology: Opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 161–171.

- Rojas-Aguirre, Y.; Aguado-Castrejón, K.; González-Méndez, I. La nanomedicina y los sistemas de liberación de fármacos:¿ la (r) evolución de la terapia contra el cáncer? Educ. Química 2016, 27, 286–291.

- Falagan-Lotsch, P.; Grzincic, E.M.; Murphy, C.J. New advances in nanotechnology-based diagnosis and therapeutics for breast cancer: An assessment of active-targeting inorganic nanoplatforms. Bioconjugate Chem. 2017, 28, 135–152.

- Matsumura, Y.; Maeda, H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: Mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res. 1986, 46, 6387–6392.

- Chen, L.; Liang, J. An overview of functional nanoparticles as novel emerging antiviral therapeutic agents. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 112, 110924.

- Ali, H.; Shirode, A.B.; Sylvester, P.W.; Nazzal, S. Preparation, characterization, and anticancer effects of simvastatin–tocotrienol lipid nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2010, 389, 223–231.

- Rodenak-Kladniew, B.; Islan, G.A.; de Bravo, M.G.; Durán, N.; Castro, G.R. Design, characterization and in vitro evaluation of linalool-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles as potent tool in cancer therapy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 154, 123–132.

- Safwat, S.; Hathout, R.M.; Ishak, R.A.; Mortada, N.D. Augmented simvastatin cytotoxicity using optimized lipid nanocapsules: A potential for breast cancer treatment. J. Liposome Res. 2017, 27, 1–10.

- Kumar, N.; Salar, R.K.; Prasad, M.; Ranjan, K. Synthesis, characterization and anticancer activity of vincristine loaded folic acid-chitosan conjugated nanoparticles on NCI-H460 non-small cell lung cancer cell line. Egypt. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2018, 5, 87–99.

- Bai, L.; Fei, W.-D.; Gu, Y.-Y.; He, M.; Du, F.; Zhang, W.-Y.; Yang, L.-L.; Liu, Y.-J. Liposomes encapsulated iridium (III) polypyridyl complexes enhance anticancer activity in vitro and in vivo. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 205, 111014.

- Li, Y.; Tan, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Fang, Y.; Rao, R.; Ren, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, W. Enhanced anticancer effect of doxorubicin by TPGS-coated liposomes with Bcl-2 siRNA-corona for dual suppression of drug resistance. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 15, 646–660.

- Samadzadeh, S.; Mousazadeh, H.; Ghareghomi, S.; Dadashpour, M.; Babazadeh, M.; Zarghami, N. In vitro anticancer efficacy of Metformin-loaded PLGA nanofibers towards the post-surgical therapy of lung cancer. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 102318.

- Torres-Pérez, S.A.; del Pilar Ramos-Godínez, M.; Ramón-Gallegos, E. Glycosylated one-step PAMAM dendrimers loaded with methotrexate for target therapy in breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 58, 101769.

- He, H.; Yuan, Q.; Bie, J.; Wallace, R.L.; Yannie, P.J.; Wang, J.; Lancina III, M.G.; Zolotarskaya, O.Y.; Korzun, W.; Yang, H. Development of mannose functionalized dendrimeric nanoparticles for targeted delivery to macrophages: Use of this platform to modulate atherosclerosis. Transl. Res. 2018, 193, 13–30.

- Gao, G.; Chen, R.; He, M.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Sun, T. Gold nanoclusters for Parkinson’s disease treatment. Biomaterials 2019, 194, 36–46.

- Kuen, C.Y.; Fakurazi, S.; Othman, S.S.; Masarudin, M.J. Increased loading, efficacy and sustained release of silibinin, a poorly soluble drug using hydrophobically-modified chitosan nanoparticles for enhanced delivery of anticancer drug delivery systems. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 379.

- Santos, A.C.; Pereira, I.; Pereira-Silva, M.; Ferreira, L.; Caldas, M.; Collado-González, M.; Magalhães, M.; Figueiras, A.; Ribeiro, A.J.; Veiga, F. Nanotechnology-based formulations for resveratrol delivery: Effects on resveratrol in vivo bioavailability and bioactivity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 180, 127–140.

- Geng, T.; Zhao, X.; Ma, M.; Zhu, G.; Yin, L. Resveratrol-loaded albumin nanoparticles with prolonged blood circulation and improved biocompatibility for highly effective targeted pancreatic tumor therapy. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 1–10.

- Wang, W.; Chen, T.; Xu, H.; Ren, B.; Cheng, X.; Qi, R.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Yan, L.; Chen, S. Curcumin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles enhanced anticancer efficiency in breast cancer. Molecules 2018, 23, 1578.

- Cancino, J.; Marangoni, V.S.; Zucolotto, V. Nanotechnology in medicine: Concepts and concerns. Química Nova 2014, 37, 521–526.

- Society, A.C. Types and Phases of Clinical Trials. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/clinical-trials/what-you-need-to-know/phases-of-clinical-trials.html (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Presant, C.A.; Scolaro, M.; Kennedy, P.; Blayney, D.; Flanagan, B.; Lisak, J.; Presant, J. Liposomal daunorubicin treatment of HIV-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Lancet 1993, 341, 1242–1243.

- Northfelt, D.W.; Martin, F.J.; Working, P.; Volberding, P.A.; Russell, J.; Newman, M.; Amantea, M.A.; Kaplan, L.D. Doxorubicin encapsulated in liposomes containing surface-bound polyethylene glycol: Pharmacokinetics, tumor localization, and safety in patients with AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1996, 36, 55–63.

- Khawar, I.A.; Kim, J.H.; Kuh, H.-J. Improving drug delivery to solid tumors: Priming the tumor microenvironment. J. Control. Release 2015, 201, 78–89.

- Gordon, A.N.; Granai, C.O.; Rose, P.G.; Hainsworth, J.; Lopez, A.; Weissman, C.; Rosales, R.; Sharpington, T. Phase II Study of Liposomal Doxorubicin in Platinum- and Paclitaxel-Refractory Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 3093–3100.

- Pillai, G. Nanomedicines for cancer therapy: An update of FDA approved and those under various stages of development. SOJ Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 1, 13.

- Guarneri, V.; Dieci, M.V.; Conte, P. Enhancing intracellular taxane delivery: Current role and perspectives of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel in the treatment of advanced breast cancer. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2012, 13, 395–406.

- Desai, N.; Trieu, V.; Yao, Z.; Louie, L.; Ci, S.; Yang, A.; Tao, C.; De, T.; Beals, B.; Dykes, D. Increased antitumor activity, intratumor paclitaxel concentrations, and endothelial cell transport of cremophor-free, albumin-bound paclitaxel, ABI-007, compared with cremophor-based paclitaxel. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 1317–1324.

- Kapoor, M.; Lee, S.L.; Tyner, K.M. Liposomal drug product development and quality: Current US experience and perspective. AAPS J. 2017, 19, 632–641.

- Euliss, L.E.; DuPont, J.A.; Gratton, S.; DeSimone, J. Imparting size, shape, and composition control of materials for nanomedicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 1095–1104.

- Sebaaly, C.; Greige-Gerges, H.; Stainmesse, S.; Fessi, H.; Charcosset, C. Effect of composition, hydrogenation of phospholipids and lyophilization on the characteristics of eugenol-loaded liposomes prepared by ethanol injection method. Food Biosci. 2016, 15, 1–10.

- Tsuji, T.; Morita, S.-y.; Ikeda, Y.; Terada, T. Enzymatic fluorometric assays for quantifying all major phospholipid classes in cells and intracellular organelles. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–13.

- Yadav, D.; Sandeep, K.; Pandey, D.; Dutta, R.K. Liposomes for drug delivery. J. Biotechnol. Biomater 2017, 7, 1–8.

- Lombardo, D.; Calandra, P.; Barreca, D.; Magazù, S.; Kiselev, M.A. Soft interaction in liposome nanocarriers for therapeutic drug delivery. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 125.

- Liu, W.; Ye, A.; Han, F.; Han, J. Advances and challenges in liposome digestion: Surface interaction, biological fate, and GIT modeling. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 263, 52–67.

- Rawicz, W.; Olbrich, K.C.; McIntosh, T.; Needham, D.; Evans, E. Effect of chain length and unsaturation on elasticity of lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2000, 79, 328–339.

- Monteiro, N.; Martins, A.; Reis, R.L.; Neves, N.M. Liposomes in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140459.

- Frezard, F. Liposomes: From biophysics to the design of peptide vaccines. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1999, 32, 181–189.

- Taylor, T.M.; Weiss, J.; Davidson, P.M.; Bruce, B.D. Liposomal nanocapsules in food science and agriculture. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 45, 587–605.

- Laouini, A.; Jaafar-Maalej, C.; Limayem-Blouza, I.; Sfar, S.; Charcosset, C.; Fessi, H. Preparation, characterization and applications of liposomes: State of the art. J. Colloid Sci. Biotechnol. 2012, 1, 147–168.

- Zawada, Z.H. Vesicles with a double bilayer. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2004, 9, 589–602.

- Inglut, C.T.; Sorrin, A.J.; Kuruppu, T.; Vig, S.; Cicalo, J.; Ahmad, H.; Huang, H.-C. Immunological and toxicological considerations for the design of liposomes. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 190.

- Ferreira, P.G.; Ferreira, V.F.; da Silva, F.D.C.; Freitas, C.S.; Pereira, P.R.; Paschoalin, V.M.F. Chitosans and Nanochitosans: Recent Advances in Skin Protection, Regeneration, and Repair. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1307.

- Bozzuto, G.; Molinari, A. Liposomes as nanomedical devices. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 975.

- Lee, S.-C.; Lee, K.-E.; Kim, J.-J.; Lim, S.-H. The effect of cholesterol in the liposome bilayer on the stabilization of incorporated retinol. J. Liposome Res. 2005, 15, 157–166.

- Sharifi, F.; Zhou, R.; Lim, C.; Jash, A.; Abbaspourrad, A.; Rizvi, S.S. Generation of liposomes using a supercritical carbon dioxide eductor vacuum system: Optimization of process variables. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 29, 163–171.

- Beltrán-Gracia, E.; López-Camacho, A.; Higuera-Ciapara, I.; Velázquez-Fernández, J.B.; Vallejo-Cardona, A.A. Nanomedicine review: Clinical developments in liposomal applications. Cancer Nanotechnol. 2019, 10, 1–40.

- Lu, R.-M.; Chen, M.-S.; Chang, D.-K.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Lin, W.-C.; Yan, S.-L.; Wang, Y.-P.; Kuo, Y.-S.; Yeh, C.-Y.; Lo, A. Targeted drug delivery systems mediated by a novel Peptide in breast cancer therapy and imaging. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66128.

- Maranhão, R.C.; Vital, C.G.; Tavoni, T.M.; Graziani, S.R. Clinical experience with drug delivery systems as tools to decrease the toxicity of anticancer chemotherapeutic agents. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2017, 14, 1217–1226.

- Yingchoncharoen, P.; Kalinowski, D.S.; Richardson, D.R. Lipid-based drug delivery systems in cancer therapy: What is available and what is yet to come. Pharmacol. Rev. 2016, 68, 701–787.

- Caddeo, C.; Pons, R.; Carbone, C.; Fernàndez-Busquets, X.; Cardia, M.C.; Maccioni, A.M.; Fadda, A.M.; Manconi, M. Physico-chemical characterization of succinyl chitosan-stabilized liposomes for the oral co-delivery of quercetin and resveratrol. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 1853–1861.

- Elmoslemany, R.M.; Abdallah, O.Y.; El-Khordagui, L.K.; Khalafallah, N.M. Propylene glycol liposomes as a topical delivery system for miconazole nitrate: Comparison with conventional liposomes. AAPS PharmSciTech 2012, 13, 723–731.

- Manconi, M.; Mura, S.; Sinico, C.; Fadda, A.M.; Vila, A.; Molina, F. Development and characterization of liposomes containing glycols as carriers for diclofenac. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2009, 342, 53–58.

- Lee, Y.; Thompson, D. Stimuli-responsive liposomes for drug delivery. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 9, e1450.

- Immordino, M.L.; Dosio, F.; Cattel, L. Stealth liposomes: Review of the basic science, rationale, and clinical applications, existing and potential. Int. J. Nanomed. 2006, 1, 297.

- Allen, T.M.; Cullis, P.R. Liposomal drug delivery systems: From concept to clinical applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 36–48.

- Perry, J.L.; Reuter, K.G.; Kai, M.P.; Herlihy, K.P.; Jones, S.W.; Luft, J.C.; Napier, M.; Bear, J.E.; DeSimone, J.M. PEGylated PRINT nanoparticles: The impact of PEG density on protein binding, macrophage association, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 5304–5310.

- Nogueira, E.; Loureiro, A.; Nogueira, P.; Freitas, J.; Almeida, C.R.; Härmark, J.; Hebert, H.; Moreira, A.; Carmo, A.M.; Preto, A. Liposome and protein based stealth nanoparticles. Faraday Discuss. 2013, 166, 417–429.

- Dams, E.T.; Laverman, P.; Oyen, W.J.; Storm, G.; Scherphof, G.L.; Van der Meer, J.W.; Corstens, F.H.; Boerman, O.C. Accelerated blood clearance and altered biodistribution of repeated injections of sterically stabilized liposomes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 292, 1071–1079.

- Ishida, T.; Kiwada, H. Accelerated blood clearance (ABC) phenomenon upon repeated injection of PEGylated liposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 354, 56–62.

- Ishida, T.; Ichihara, M.; Wang, X.; Yamamoto, K.; Kimura, J.; Majima, E.; Kiwada, H. Injection of PEGylated liposomes in rats elicits PEG-specific IgM, which is responsible for rapid elimination of a second dose of PEGylated liposomes. J. Control. Release 2006, 112, 15–25.

- Lila, A.S.A.; Kiwada, H.; Ishida, T. The accelerated blood clearance (ABC) phenomenon: Clinical challenge and approaches to manage. J. Control. Release 2013, 172, 38–47.

- Ambegia, E.; Ansell, S.; Cullis, P.; Heyes, J.; Palmer, L.; MacLachlan, I. Stabilized plasmid–lipid particles containing PEG-diacylglycerols exhibit extended circulation lifetimes and tumor selective gene expression. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2005, 1669, 155–163.

- Webb, M.S.; Saxon, D.; Wong, F.M.; Lim, H.J.; Wang, Z.; Bally, M.B.; Choi, L.S.; Cullis, P.R.; Mayer, L.D. Comparison of different hydrophobic anchors conjugated to poly (ethylene glycol): Effects on the pharmacokinetics of liposomal vincristine. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 1998, 1372, 272–282.