| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Horacio Bach | -- | 3361 | 2022-12-22 22:50:38 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | + 1 word(s) | 3362 | 2022-12-23 05:15:32 | | | | |

| 3 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 3362 | 2022-12-23 05:18:47 | | | | |

| 4 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 3362 | 2022-12-23 05:22:16 | | |

Video Upload Options

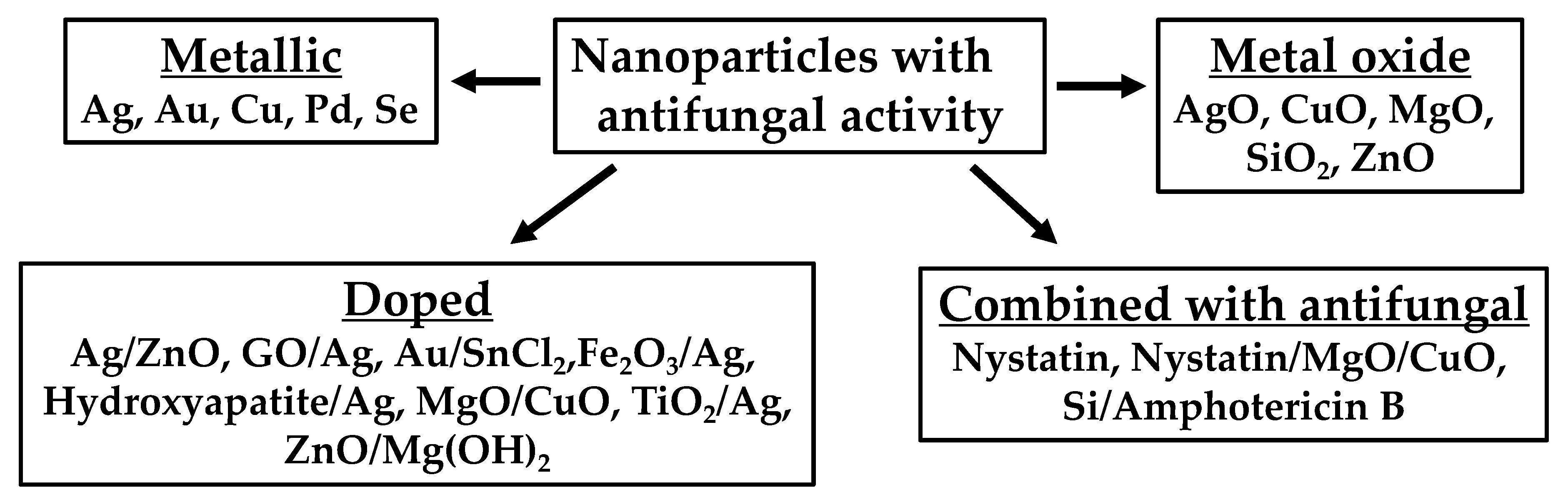

Fungi were initially included as a part of Kingdom Plantae but in 1969 were grouped into Kingdom Fungi, which comprises diverse groups with different morphologies, such as unicellular yeasts and multicellular organisms. The rate of antifungal resistance development has been called “unprecedented”. This is because immunocompromised individuals are at a higher risk of fungal infections than healthy individuals. Moreover, medical advancements over the past few decades and the HIV epidemic have increased the number of immunocompromised people, which has, in turn, shifted fungal infections from being an infrequent cause of disease to being an important contributor to human morbidity and mortality worldwide. There are six antifungal drug classes, and this scarcity, combined with the increasing resistance, has led to the need for novel treatments. The appearance of resistant species of fungi to the existent antimycotics is challenging for the scientific community. One emergent technology is the application of nanotechnology to develop novel antifungal agents. Metal nanoparticles (NPs) have shown promising results as an alternative to classical antimycotics.

1. Nanoparticle Formulation as Antifungal Agents

| Type of NP | Shape | Size (nm) | Organism(s) Tested | MIC100 (µg/mL) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | Spherical | 3 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae (KCTC 7296) Trichosporon beigelii (KCTC 7707) Candida albicans (ATCC 90028) |

2 | [2] |

| Spherical | 1–21 | Candida albicans Candida glabrata Candida parapsilosis Candida tropicalis Fusarium solani Fusarium moniliforme Fusarium oxysporum Aspergillus flavus Aspergillus fumigatus Aspergillus terrus Sporothrix schenckii Cryptococcus neoformans |

0.25 0.125 0.25 0.125 1 2 4 1 2 2 0.25 0.25 |

[3] | |

| Spherical | 5 | Candida albicans (324LA/84) Candida glabrata (ATCC 90030) Candida albicans (ATCC 10321) Candida glabrata (D1) |

0.4–0.8 0.4–0.8 0.8–1.6 1.6–3.3 |

[4] | |

| Spherical | 7 | Aspergillus flavus Aspergillus fumigatus |

100 100 |

[5] | |

| Spherical | 25 | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida parapsilosis Candida tropicalis |

0.42 0.21 1.690 0.840 |

[6] | |

| Spherical | 5–20 | Trichosporon asahii (CBS2479) Trichosporon asahii (BZ701) Trichosporon asahii (BZ702) Trichosporon asahii (BZ703) Trichosporon asahii (BZ704) Trichosporon asahii (BZ705) Trichosporon asahii (BZ705R) Trichosporon asahii (BZ901) Trichosporon asahii (BZ902) Trichosporon asahii (BZ121) Trichosporon asahii (BZ122) Trichosporon asahii (BZ123) Trichosporon asahii (BZ124) Trichosporon asahii (BZ125) Trichosporon asahii (CBS8904) Trichosporon asahii (CBS7137) Trichosporon asahii (CBS8520) |

0.50 0.67 0.50 1.00 0.67 0.50 0.50 0.67 1.00 0.83 0.67 0.50 0.67 0.83 0.50 0.67 0.67 |

[7] | |

| Spherical | 15–25 | Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) Candida albicans (ATCC 90028) Candida glabrata (ATCC 90030) Candida parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) |

1.56 6.25 3.12 6.25 |

[8] | |

| Spherical | 25 | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida parapsilosis Candida tropicalis |

27 27 27 27 |

[6] | |

| Spherical to polyhedric | 73.72 | Trichophyton rubrum (n = 8) Trichophyton rubrum (ATCC MYA 4438) |

0.5–2.5 <0.25 |

[9] | |

| Spherical | 76.14 | Trichophyton rubrum (n = 8) Trichophyton rubrum (ATCC MYA 4438) |

>7.5 >7.5 |

[9] | |

| Spherical | 100.6 | Trichophyton rubrum (n = 8) Trichophyton rubrum (ATCC MYA 4438) |

0.5–5 0.5 |

[9] | |

| NR | NR | Fusarium graminearum | 4.68 | [10] | |

| NR | NR | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida parapsilosis Candida tropicalis |

0.42 0.21 1.69 0.84 |

[6] | |

| NR | NR | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida parapsilosis Candida tropicalis |

0.052 0.1 0.84 0.42 |

[6] | |

| NR | NR | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida parapsilosis Candida tropicalis |

3.38 3.38 3.38 3.38 |

[6] | |

| NR | 20–25 | Aspergillus niger Candida albicans Cryptococcus neoformans |

25 6 3 |

[11] | |

| NR | NR | Fusarium graminearum | 12.5 | [10] | |

| Ag/ZnO | Spherical | 7/477 | Aspergillus flavus Aspergillus fumigatus |

50/10 50/10 |

[5] |

| qAg | Spherical | 2–3 | Candida albicans | 0.07 | [12] |

| Cu | Spherical | 10–40 | Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) Candida albicans (Clinical strain C) Candida albicans (Clinical strain E) |

129.7 1037.5 518.8 |

[13] |

| Wires | 20–30 µm, 30–60 nm diameter | Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) Candida albicans (Clinical strain C) Candida albicans (Clinical strain E) |

260.3 260.3 260.3 |

[13] | |

| γ-Fe2O3/Ag | NR | 20–40 (Ag) + 5 (γ-Fe2O3) | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida tropicalis (5) Candida parapsilosis (6) |

1.9 1.9 31.3 31.3 |

[14] |

| Fe3O4/Ag | NR | ~5 (Ag) + ~70 (Fe3O4) | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida tropicalis (5) Candida parapsilosis (6) |

1.9 1.9 3.9 7.8 |

[14] |

| GO/Ag | Spherical | 10–35 | Fusarium graminearum | 9.37 | [10] |

| HA/Ag | Rod/Spherical | 12–27 | Candida albicans | 62.5 | [15] |

| MgO 500 °C calcination |

Flaked layers | 52 ± 18 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

156 312 |

[16] |

| MgO 1000 °C calcination |

Flaked layers | 96 ± 33 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[16] |

| Pd | Spherical | 9 ± 3.9 | Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) Aspergillus niger |

212.5 200 |

[17] |

| Se | Spherical | 80–200 | Candida albicans (ATCC 76615) Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) |

100 70 |

[18] |

| Se | Spherical | 37–46 | Aspergillus fumigatus (TIMML-025) Aspergillus fumigatus (TIMML-050) Aspergillus fumigatus (TIMML-379) |

0.5 0.5 1 |

[19] |

| Silica/AmB | NR | 5 | Candida albicans Candida krusei Candida parapsilosis Candida glabrata Candida tropicalis |

100 1000 1000–2000 300 100 |

[20] |

| TiO2/Ag + NaHB4 | NR | 250–300 | Aspergillus niger Candida albicans Cryptococcus neoformans |

25 12.5 12.5 |

[11] |

| TiO2/Ag + UV | NR | 250–300 | Aspergillus niger Candida albicans Cryptococcus neoformans |

12.5 6 3 |

[11] |

| ZnO | Spherical | 20–40 | Candida albicans (n = 125) | 0.2–296 | [21] |

| Spherical | 477 | Aspergillus flavus Aspergillus fumigatus |

20 20 |

[5] | |

| ZnO 500 °C calcination |

Spherical + cylindrical | 51 ± 13 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

156 312 |

[16] |

| ZnO 1000 °C calcination |

Hexagonal bars | 53 ± 17 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

156 312 |

[16] |

| ZnO/Mg(OH)2 25 °C synthesis |

Flakes + bars | 54 ± 17 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

156 312 |

[16] |

| ZnO NP 25 °C synthesis |

Hexagonal bars + ovoidal | 63 ± 18 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[16] |

| ZnO/Mg(OH)2 70 °C synthesis |

Flakes + bars | 71 ± 22 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[16] |

| ZnO 25 °C synthesis, hydrothermal |

Prisms with pyramidal ends | 77 ± 31 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[16] |

| ZnO/Mg(OH)2 NP 25 °C synthesis, hydrothermal 160 °C |

Flakes + bars | 88 ± 30 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[16] |

| ZnO/Mg(OH)2 70 °C synthesis, hydrothermal 160 °C |

Flakes + bars | 98 ± 41 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[16] |

| ZnO/MgO 25 °C synthesis, 500 °C calcination |

Flakes | 139 ± 49 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[16] |

| ZnO/MgO 70 °C synthesis, 500 °C calcination |

Flakes | 161 ± 44 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[16] |

| ZnO/MgO 70 °C synthesis, 1000 °C calcination |

Flakes | 219 ± 39 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

625 625 |

[16] |

| ZnO | NR | NR | Candida albicans (n = 10) | 0.02–269 | [22] |

| Type of NP | Shape | Size (nm) | Organism(s) Tested | MIC50 (µg/mL) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | Spherical | 30–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

4 9 9 |

[23] |

| Ag | Cubical | 40–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

1 7 7 |

[23] |

| Ag | Wires | 250–300 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

5 12 11 |

[23] |

| Au | Cubical | 30–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

3 10 11 |

[23] |

| Au | Spherical | 35–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

8 13 12 |

[23] |

| Au | Wires | 300–500 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

7 15 15 |

[23] |

| ZnO | Spherical | 20–40 | Candida albicans (n = 125) | 8.2 | [21] |

| ZnO | NR | NR | Candida albicans (n = 10) | 5 | [22] |

| Type of NP | Shape | Size (nm) | Organism(s) Tested | MIC80 (µg/mL) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AuNP + SnCl2 as reducing agent | Polygonal, almost spherical | 5–50 | Candida albicans Candida tropicalis Candida glabrata |

16 16 16 |

[24] |

| AuNP + NaBH4 as reducing agent | Spherical | 3–20 | Candida albicans Candida tropicalis Candida glabrata |

4 4 4 |

[24] |

| Type of NP | Shape | Size (nm) | Organism(s) Tested | MIC90 (µg/mL) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMW Chitosan NP ± 1 mg/mL chitosan | Spherical | 174 ± 38.47 | Candida albicans Fusarium solani Aspergillus niger |

250 1000 NR |

[25] |

| HMW Chitosan NP ± 1 mg/mL chitosan | Spherical | 210 ± 24.54 | Candida albicans Fusarium solani Aspergillus niger |

1000 500 NR |

[25] |

| LMW Chitosan NP ± 2 mg/mL chitosan | Spherical | 233 ± 41.38 | Candida albicans Fusarium solani Aspergillus niger |

857.2 857.2 NR |

[25] |

| HMW Chitosan NP ± 2 mg/mL chitosan | Spherical | 263 ± 86.44 | Candida albicans Fusarium solani Aspergillus niger |

857.2 857.2 1714 |

[25] |

| LMW Chitosan NP ± 3 mg/mL chitosan | Spherical | 255 ± 42.81 | Candida albicans Fusarium solani Aspergillus niger |

607.2 1214 NR |

[25] |

| HMW Chitosan NP ± 3 mg/mL chitosan | Spherical | 301 ± 72.85 | Candida albicans Fusarium solani Aspergillus niger |

607.2 1214.3 2428.6 |

[25] |

| Ag | Cubical | 40–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

8 30 31 |

[23] |

| Ag | Spherical | 30–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

11 37 35 |

[23] |

| Ag | Wires | 250–300 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

21 51 48 |

[23] |

| Au | Cubical | 30–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

10 45 46 |

[23] |

| Au | Spherical | 35–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

15 47 48 |

[23] |

| Au | Wires | 300–500 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

30 70 73 |

[23] |

| ZnO | Spherical | 20–40 | Candida albicans (n = 125) | 17.76 | [21] |

| ZnO | NR | NR | Candida albicans (n = 10) | 11.3 |

| Type of NP | Shape | Size (nm) | Organism(s) Tested | Activity (mm) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuO | Spherical | 3–30 | Fusarium equiseti Fusarium oxysporum Fusarium culmorum |

25 20 19 |

[26] |

| Pd | Spherical | 200 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | Day 2: 3.6 Day 4: 1.6 |

[27] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Day 2: 12.2 Day 4: 10.9 |

||||

| Pd | Spherical | 220 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | Day 2: 7.9 Day 4: 6.3 |

[27] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Day 2: 5.1 Day 4: 4.7 |

||||

| Pd | Spherical | 250 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | Day 2: 2.4 Day 4: 0.7 |

[27] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Day 2: 10.4 Day 4: 9.6 |

||||

| Pd | Spherical | 350 | Fusarium oxysporum | Day 2: 1.5 Day 4: 1.3 |

[27] |

| Pd | Spherical | 550 | Fusarium oxysporum | Day 2: 3.8 Day 4: 3.3 |

[27] |

| Nystatin/MgO/CuO | Spherical | 8000–10000 | Candida albicans (AH201) Candida albicans (AH267) |

24.5 ± 1.7 14.3 ± 1.2 |

[28] |

| Nystatin | Spherical | 8000–10000 | Candida albicans (AH201) Candida albicans (AH267) |

0.41 ± 0.23 0.5 ± 0.21 |

[28] |

| MgO/CuO | Spherical | 8000–10000 | Candida albicans (AH201) Candida albicans (AH267) |

19.2 ± 1.6 1.3 ± 0.61 |

[28] |

| TiO2/BPE B | NR | NR | Candida albicans (ATCC 14053) | 11.2 ± 0.02 | [29] |

| TiO2/BPE C | NR | NR | Candida albicans (ATCC 14053) | 15.9 ± 0.04 | [29] |

| TiO2/BPE D | NR | NR | Candida albicans (ATCC 14053) | 13.5 ± 0.04 | [29] |

| TiO2/BPE E | NR | NR | Candida albicans (ATCC 14053) | 14.6 ± 0.01 | [29] |

| TiO2/BPE B | NR | NR | Penicillum chrysogenum (MTCC 5108) | 10.2 ± 0.05 | [29] |

| TiO2/BPE C | NR | NR | Penicillum chrysogenum (MTCC 5108) | 18.0 ± 0.03 | [29] |

| TiO2/BPE D | NR | NR | Penicillum chrysogenum (MTCC 5108) | 15.0 ± 0.04 | [29] |

| TiO2/BPE E | NR | NR | Penicillum chrysogenum (MTCC 5108) | 13.5 ± 0.08 | [29] |

| Type of NP | Shape | Size (nm) | Organism(s) Tested | Activity (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | NR | 20–100 | Cladosporium cladosporioides Aspergillus niger |

50 µg/mL → 90 50 µg/mL → 70 |

[30] |

| Ag | Polygonal | 35 ± 15 | Candida tropicalis Saccharomyces boulardii |

25 µg/mL → >95 50 µg/mL → >95 25 µg/mL → <50 50 µg/mL → >95 |

[31] |

| Ag | Spherical | 5 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | 13 µg/mL → 73 26 µg/mL → 82 56 µg/mL → 89 |

[32] |

| Ag | Spherical | 24 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | 13 µg/mL → 74 26 µg/mL → 82 56 µg/mL → 89 |

[32] |

| ZnO | Spherical | 30–45 | Erythricium salmonicolor | 12 mmol/L, day 7 → 71.3 12 mmol/L, day 10 → 51.1 9 mmol/L, day 7 → 58.3 9 mmol/L, day 10 → 44.6 6 mmol/L, day 7 → 48.9 6 mmol/L, day 10 → 23.6 3 mmol/L, day 7 → 36.9 3 mmol/L, day 10 → 14.1 |

[33] |

| Ag | NR | NR | Rhizoctonia solani (AG1) Rhizoctonia solani (AG4) Macrophomina phaseolina Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Trichoderma harzianum Pythium aphanidermatum |

6 µg/mL → 75 8 µg/mL → 80 10 µg/mL → 90 12 µg/mL → 90 14 µg/mL → 90 16 µg/mL → 100 6 µg/mL → ≥90 8 µg/mL → ≥90 10 µg/mL → ≥90 12 µg/mL → 100 14 µg/mL → 100 16 µg/mL → 100 6 µg/mL → 100 8 µg/mL → 100 10 µg/mL → 100 12 µg/mL → 100 14 µg/mL → 100 16 µg/mL → 100 6 µg/mL → ≥95 8 µg/mL → 100 10 µg/mL → 100 12 µg/mL → 100 14 µg/mL → 100 16 µg/mL → 100 6 µg/mL → 80 8 µg/mL → 84 10 µg/mL → 90 12 µg/mL → 100 14 µg/mL → 100 16 µg/mL → 100 6 µg/mL → 100 8 µg/mL → 100 10 µg/mL → 100 12 µg/mL → 100 14 µg/mL → 100 16 µg/mL → 100 |

[34] |

| Ag | Spherical | 10–20 | Bipolaris sorokiniana | ≥2 µg/mL → 100 | [35] |

| Ag | Spherical | 1–9 | Aspergillus flavus | 5 µg/mL → 0 15 µg/mL → 30 25 µg/mL → 58 35 µg/mL → 85 45 µg/mL → 98 60 µg/mL → 100 |

[36] |

| PEI1/Ag | Spherical | 20.6 | Rhizopus arrhizus | 1.6 µg/mL → 97 | [37] |

| PEI2/Ag | Spherical | 4.24 | 6.5 µg/mL → 94 | ||

| SiO2 | Spherical | 9.92–19.8 | Rhizoctonia solani | 100 µg/mL → 93–100 | [38] |

2. Antifungal Classes and Combination with Nanoparticles

| Class | Examples | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Allylamines | Terbinafine Naftifine |

Squalene epoxidase inhibition, responsible for conversion of squalene to ergosterol |

| Azoles | Clotrimazole Miconazole Ketoconazole Fluconazole Itrazonacole |

C14-α demethylation inhibition of lanosterol, inhibiting ergosterol synthesis |

| Echinocandins | Caspofungin Micafungin Anidulafungin |

β-(1,3)-D-glucan synthase inhibition, interfering with cell wall synthesis |

| Polyenes | Amphotericin B Nystatin Candicidin |

Ergosterol binding, forming pores and causing leakage, inhibiting proper transport mechanisms |

| Antimetabolites | Flucytosine | Pyrimidine analogue, interfering with nucleic acid synthesis |

| Triterpenoids | Ibrexafungerp | β-(1,3)-D-glucan synthase inhibition, interfering with cell wall synthesis |

References

- Lee, Y.; Puumala, E.; Robbins, N.; Cowen, L.E. Antifungal drug resistance: Molecular mechanisms in Candida albicans and beyond. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 3390–3411.

- Kim, K.J.; Sung, W.S.; Suh, B.K.; Moon, S.K.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, J.G.; Lee, D.G. Antifungal activity and mode of action of silver nano-particles on Candida albicans. Biometals 2009, 22, 235–242.

- Wang, D.; Xue, B.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhou, Y. Fungus-mediated green synthesis of nano-silver using Aspergillus sydowii and its antifungal/antiproliferative activities. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10356.

- Monteiro, D.R.; Gorup, L.F.; Silva, S.; Negri, M.; De Camargo, E.R.; Oliveira, R.; Barbosa, D.D.B.; Henriques, M. Silver colloidal nanoparticles: Antifungal effect against adhered cells and biofilms of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata. Biofouling 2011, 27, 711–719.

- Auyeung, A.; Casillas-Santana, M.A.; Martinez-Castanon, G.A.; Slavin, Y.N.; Zhao, W.; Asnis, J.; Häfeli, U.O.; Bach, H. Effective control of molds using a combination of nanoparticles. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169940.

- Panáček, A.; Kolář, M.; Večeřová, R.; Prucek, R.; Soukupová, J.; Kryštof, V.; Hamal, P.; Zbořil, R.; Kvítek, L. Antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles against Candida spp. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6333–6340.

- Xia, Z.K.; Ma, Q.H.; Li, S.Y.; Zhang, D.Q.; Cong, L.; Tian, Y.L.; Yang, R.Y. The antifungal effect of silver nanoparticles on Trichosporon asahii. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2016, 49, 182–188.

- Różalska, B.; Sadowska, B.; Budzyńska, A.; Bernat, P.; Różalska, S. Biogenic nanosilver synthesized in Metarhizium robertsii waste mycelium extract—As a modulator of Candida albicans morphogenesis, membrane lipidome and biofilm. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194254.

- Pereira, L.; Dias, N.; Carvalho, J.; Fernandes, S.; Santos, C.; Lima, N. Synthesis, characterization and antifungal activity of chemically and fungal-produced silver nanoparticles against Trichophyton rubrum. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 117, 1601–1613.

- Chen, J.; Sun, L.; Cheng, Y.; Lu, Z.; Shao, K.; Li, T.; Hu, C.; Han, H. Graphene oxide-silver nanocomposite: Novel agricultural antifungal agent against Fusarium graminearum for crop disease prevention. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 24057–24070.

- Martinez-Gutierrez, F.; Olive, P.L.; Banuelos, A.; Orrantia, E.; Nino, N.; Sanchez, E.M.; Ruiz, F.; Bach, H.; Av-Gay, Y. Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of antimicrobial and cytotoxic effect of silver and titanium nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 2010, 6, 681–688.

- Selvaraj, M.; Pandurangan, P.; Ramasami, N.; Rajendran, S.B.; Sangilimuthu, S.N.; Perumal, P. Highly potential antifungal activity of quantum-sized silver nanoparticles against Candida albicans. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 173, 55–66.

- Martínez, A.; Apip, C.; Meléndrez, M.F.; Domínguez, M.; Sánchez-Sanhueza, G.; Marzialetti, T.; Catalán, A. Dual antifungal activity against Candida albicans of copper metallic nanostructures and hierarchical copper oxide marigold-like nanostructures grown in situ in the culture medium. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 130, 1883–1892.

- Prucek, R.; Tuček, J.; Kilianová, M.; Panáček, A.; Kvítek, L.; Filip, J.; Kolář, M.; Tománková, K.; Zbořil, R. The targeted antibacterial and antifungal properties of magnetic nanocomposite of iron oxide and silver nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 4704–4713.

- Zamperini, C.A.; André, R.S.; Longo, V.M.; Mima, E.G.; Vergani, C.E.; Machado, A.L.; Varela, J.A.; Longo, E. Antifungal applications of Ag-decorated hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013, e174398.

- De la Rosa-García, S.C.; Martínez-Torres, P.; Gómez-Cornelio, S.; Corral-Aguado, M.A.; Quintana, P.; Gómez-Ortíz, N.M. Antifungal activity of ZnO and MgO nanomaterials and their mixtures against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides strains from tropical fruit. J. Nanomater. 2018, 2018, e3498527.

- Athie-García, M.S.; Piñón-Castillo, H.A.; Muñoz-Castellanos, L.N.; Ulloa-Ogaz, A.L.; Martínez-Varela, P.I.; Quintero-Ramos, A.; Duran, R.; Murillo-Ramirez, J.G.; Orrantia-Borunda, E. Cell wall damage and oxidative stress in Candida albicans ATCC 10231 and Aspergillus niger caused by palladium nanoparticles. Toxicol. Vitr. 2018, 48, 111–120.

- Parsameher, N.; Rezaei, S.; Khodavasiy, S.; Salari, S.; Hadizade, S.; Kord, M.; Mousavi, S.A.A. Effect of biogenic selenium nanoparticles on ERG11 and CDR1 gene expression in both fluconazole-resistant and -susceptible Candida albicans isolates. Curr. Med. Mycol. 2017, 3, 16–20.

- Bafghi, M.H.; Nazari, R.; Darroudi, M.; Zargar, M.; Zarrinfar, H. The effect of biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles on the expression of CYP51A and HSP90 antifungal resistance genes in Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus. Biotechnol. Prog. 2022, 38, e3206.

- Paulo, C.S.O.; Vidal, M.; Ferreira, L.S. Antifungal nanoparticles and surfaces. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 2810–2817.

- Hosseini, S.S.; Ghaemi, E.; Noroozi, A.; Niknejad, F. Zinc oxide nanoparticles inhibition of initial adhesion and ALS1 and ALS3 gene expression in Candida albicans strains from urinary tract infections. Mycopathologia 2019, 184, 261–271.

- Hosseini, S.S.; Joshaghani, H.; Shokohi, T.; Ahmadi, A.; Mehrbakhsh, Z. Antifungal activity of ZnO nanoparticles and nystatin and downregulation of SAP1-3 genes expression in fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans isolates from vulvovaginal candidiasis. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 385–394.

- Jebali, A.; Hajjar, F.H.E.; Pourdanesh, F.; Hekmatimoghaddam, S.; Kazemi, B.; Masoudi, A.; Daliri, K.; Sedighi, N. Silver and gold nanostructures: Antifungal property of different shapes of these nanostructures on Candida species. Med. Mycol. 2014, 52, 65–72.

- Ahmad, T.; Wani, I.A.; Lone, I.H.; Ganguly, A.; Manzoor, N.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmed, J.; Al-Shihri, A.S. Antifungal activity of gold nanoparticles prepared by solvothermal method. Mater. Res. Bull. 2013, 48, 12–20.

- Ing, L.Y.; Zin, N.M.; Sarwar, A.; Katas, H. Antifungal activity of chitosan nanoparticles and correlation with their physical properties. Int. J. Biomat. 2012, 2012, 632698.

- Bramhanwade, K.; Shende, S.; Bonde, S.; Gade, A.; Rai, M. Fungicidal activity of Cu nanoparticles against Fusarium causing crop diseases. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2016, 14, 229–235.

- Osonga, F.J.; Kalra, S.; Miller, R.M.; Isika, D.; Sadik, O.A. Synthesis, characterization and antifungal activities of eco-friendly palladium nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 5894–5904.

- Abid, S.; Uzair, B.; Niazi, M.B.K.; Fasim, F.; Bano, S.A.; Jamil, N.; Batool, R.; Sajjad, S. Bursting the virulence traits of MDR strain of Candida albicans using sodium alginate-based microspheres containing nystatin-loaded MgO/CuO nanocomposites. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 1157–1174.

- Chougale, R.; Kasai, D.; Nayak, S.; Masti, S.; Nasalapure, A.; Raghu, A.V. Design of eco-friendly PVA/TiO2 based nanocomposites and their antifungal activity study. Green Mater. 2020, 8, 40–48.

- Pulit, J.; Banach, M.; Szczygłowska, R.; Bryk, M. Nanosilver against fungi. Silver nanoparticles as an effective biocidal factor. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2013, 60, 795–798.

- Guerra, J.D.; Sandoval, G.; Avalos-Borja, M.; Pestryakov, A.; Garibo, D.; Susarrey-Arce, A.; Bogdanchikova, N. Selective antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles: A comparative study between Candida tropicalis and Saccharomyces boulardii. Colloids Interface Sci. Commun. 2020, 37, 100280.

- Aguilar-Méndez, M.A.; San Martín-Martínez, E.; Ortega-Arroyo, L.; Cobián-Portillo, G.; Sánchez-Espíndola, E. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles: Effect on phytopathogen Colletotrichum gloesporioides. J. Nanopart. Res. 2011, 13, 2525–2532.

- Arciniegas-Grijalba, P.A.; Patiño-Portela, M.C.; Mosquera-Sánchez, L.P.; Guerrero-Vargas, J.A.; Rodríguez-Páez, J.E. ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) and their antifungal activity against coffee fungus Erythricium salmonicolor. Appl. Nanosci. 2017, 7, 225–241.

- Kim, S.W.; Jung, J.H.; Lamsal, K.; Kim, Y.S.; Min, J.S.; Lee, Y.S. Antifungal effects of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) against various plant pathogenic fungi. Mycobiology 2012, 40, 53–58.

- Mishra, S.; Singh, B.R.; Singh, A.; Keswani, C.; Naqvi, A.H.; Singh, H.B. Biofabricated silver nanoparticles act as a strong fungicide against Bipolaris sorokiniana causing spot blotch disease in wheat. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97881.

- Zhao, J.; Wang, L.; Xu, D.; Lu, Z. Involvement of ROS in nanosilver-caused suppression of aflatoxin production from Aspergillus flavus. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 23021–23026.

- Tiwari, A.K.; Gupta, M.K.; Pandey, G.; Tilak, R.; Narayan, R.J.; Pandey, P.C. Size and zeta potential clicked germination attenuation and anti-sporangiospores activity of PEI-functionalized silver nanoparticles against COVID-19 associated Mucorales (Rhizopus arrhizus). Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2235.

- Abdelrhim, A.; Mazrou, Y.; Nehela, Y.; Atallah, O.; El-Ashmony, R.; Dawood, M. Silicon dioxide nanoparticles induce innate immune responses and activate antioxidant machinery in wheat against Rhizoctonia solani. Plants 2021, 10, 2758.

- Cioffi, N.; Torsi, L.; Ditaranto, N.; Tantillo, G.; Ghibelli, L.; Sabbatini, L.; Bleve-Zacheo, T.; D’Alessio, M.; Zambonin, P.G.; Traversa, E. Copper nanoparticle/polymer composites with antifungal and bacteriostatic properties. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 5255–5262.

- Alexander, J.W. History of the medical use of silver. Surg. Infect. 2009, 10, 289–292.

- Xiong, Y.; Brunson, M.; Huh, J.; Huang, A.; Coster, A.; Wendt, K.; Fay, J.; Qin, D. The role of surface chemistry on the toxicity of Ag nanoparticles. Small 2013, 9, 2628–2638.

- Kim, S.W.; Kim, K.S.; Lamsal, K.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, S.B.; Jung, M.Y.; Sim, S.J.; Kim, H.S.; Chang, S.J.; Kim, J.K.; et al. An in vitro study of the antifungal effect of silver nanoparticles on oak wilt pathogen Raffaelea sp. J. Microb. Microbiol. 2009, 19, 760–764.

- Ouda, S.M. Antifungal activity of silver and copper nanoparticles on two plant pathogens, Alternaria alternata and Botrytis cinerea. Res. J. Microbiol. 2014, 9, 34–42.

- Sousa, C.A.; Soares, H.M.V.M.; Soares, E.V. Metal(loid) oxide (Al2O3, Mn3O4, SiO2 and SnO2) nanoparticles cause cytotoxicity in yeast via intracellular generation of reactive oxygen species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 6257–6269.

- Eda, G.; Fanchini, G.; Chhowalla, M. Large-area ultrathin films of reduced graphene oxide as a transparent and flexible electronic material. Nat. Nanotech. 2008, 3, 270–274.

- Mukherjee, K.; Acharya, K.; Biswas, A.; Jana, N.R. TiO2 nanoparticles co-doped with nitrogen and fluorine as visible-light-activated antifungal agents. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 2016–2025.

- Boxi, S.S.; Mukherjee, K.; Paria, S. Ag doped hollow TiO2 nanoparticles as an effective green fungicide against Fusarium solani and Venturia inaequalis phytopathogens. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 085103.

- Wani, A.H.; Shah, M.A. A unique and profound effect of MgO and ZnO nanoparticles on some plant pathogenic fungi. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 2, 40–44.

- He, L.; Liu, Y.; Mustapha, A.; Lin, M. Antifungal activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles against Botrytis cinerea and Penicillium expansum. Microbiol. Res. 2011, 166, 207–215.

- Navale, G.R.; Shinde, S.S. Antimicrobial activity of ZnO nanoparticles against pathogenic bacteria and fungi. JSM Nanotechnol. Nanomed. 2015, 3, 1033.

- Babele, P.K.; Thakre, P.K.; Kumawat, R.; Tomar, R.S. Zinc oxide nanoparticles induce toxicity by affecting cell wall integrity pathway, mitochondrial function and lipid homeostasis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Chemosphere 2018, 213, 65–75.

- Kumari, M.; Giri, V.P.; Pandey, S.; Kumar, M.; Katiyar, R.; Nautiyal, C.S.; Mishra, A. An insight into the mechanism of antifungal activity of biogenic nanoparticles than their chemical counterparts. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2019, 157, 45–52.

- Kalagatur, N.K.; Nirmal Ghosh, O.S.; Sundararaj, N.; Mudili, V. Antifungal activity of chitosan nanoparticles encapsulated with Cymbopogon martinii essential oil on plant pathogenic fungi Fusarium graminearum. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 610.

- Molnár, Z.; Bódai, V.; Szakacs, G.; Erdélyi, B.; Fogarassy, Z.; Sáfrán, G.; Varga, T.; Kónya, Z.; Tóth-Szeles, E.; Szűcs, R.; et al. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles by thermophilic filamentous fungi. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3943.

- Ruiz-Romero, P.; Valdez-Salas, B.; González-Mendoza, D.; Mendez-Trujillo, V. Antifungal effects of silver phytonanoparticles from Yucca shilerifera against strawberry soil-borne pathogens: Fusarium solani and Macrophomina phaseolina. Mycobiology 2018, 46, 47–51.

- Gajbhiye, M.; Kesharwani, J.; Ingle, A.; Gade, A.; Rai, M. Fungus-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their activity against pathogenic fungi in combination with fluconazole. Nanomedicine 2009, 5, 382–386.

- Singh, M.; Kumar, M.; Kalaivani, R.; Manikandan, S.; Kumaraguru, A.K. Metallic silver nanoparticle: A therapeutic agent in combination with antifungal drug against human fungal pathogen. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 36, 407–415.

- Li, X.; Xu, H.; Chen, Z.-S.; Chen, G. Biosynthesis of nanoparticles by microorganisms and their applications. J. Nanomater. 2011, 2011, 1–16.

- He, S.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Gu, N. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using the bacteria Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Mater. Lett. 2007, 61, 3984–3987.

- Durán, N.; Marcato, P.D.; Alves, O.L.; De Souza, G.I.; Esposito, E. Mechanistic aspects of biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by several Fusarium oxysporum strains. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2005, 3, 8.

- Gintjee, T.J.; Donnelley, M.A.; Thompson, G.R. Aspiring antifungals: Review of current antifungal pipeline developments. J. Fungi. 2020, 6, 28.

- Dixon, D.M.; Walsh, T.J. Chapter 76 Antifungal agents. In Medical Microbiology, 4th ed.; University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston: Galveston, TX, USA, 1996.

- Jallow, S.; Govender, N.P. Ibrexafungerp: A first-in-class oral triterpenoid glucan synthase inhibitor. J. Fungi. 2021, 7, 163.

- Cournia, Z.; Ullmann, G.M.; Smith, J.C. Differential effects of cholesterol, ergosterol and lanosterol on a dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine membrane: A molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Phys, Chem. B 2007, 111, 1786–1801.

- Vermitsky, J.-P.; Earhart, K.D.; Smith, W.L.; Homayouni, R.; Edlind, T.D.; Rogers, P.D. Pdr1 regulates multidrug resistance in Candida glabrata: Gene disruption and genome-wide expression studies. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 61, 704–722.

- Flowers, S.A.; Barker, K.S.; Berkow, E.L.; Toner, G.; Chadwick, S.G.; Gygax, S.E.; Morschhäuser, J.; Rogers, P.D. Gain-of-function mutations in UPC2 are a frequent cause of ERG11 upregulation in azole-resistant clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 2012, 11, 1289–1299.

- Morschhäuser, J.; Barker, K.S.; Liu, T.T.; Blaß-Warmuth, J.; Homayouni, R.; Rogers, P.D. The transcription factor Mrr1p controls expression of the MDR1 efflux pump and mediates multidrug resistance in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3, e164.

- Sagatova, A.A.; Keniya, M.V.; Wilson, R.K.; Monk, B.C.; Tyndall, J.D.A. Structural insights into binding of the antifungal drug fluconazole to Saccharomyces cerevisiae lanosterol 14α-demethylase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4982–4989.

- Chandra, J.; Kuhn, D.M.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Hoyer, L.L.; McCormick, T.; Ghannoum, M.A. Biofilm formation by the fungal pathogen Candida albicans: Development, architecture, and drug resistance. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 5385–5394.

- Marichal, P.; Koymans, L.; Willemsens, S.; Bellens, D.; Verhasselt, P.; Luyten, W.; Borgers, M.; Ramaekers, F.C.; Odds, F.C.; Bossche, H.V. Contribution of mutations in the cytochrome P450 14α-demethylase (Erg11p, Cyp51p) to azole resistance in Candida albicans. Microbiology 1999, 145, 2701–2713.

- Liu, Y.; Cui, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, S.; Ma, J. Chitosan nanoparticles to enhance the inhibitory effect of natamycin on Candida albicans. J. Nanomater. 2021, 2021, 6644567.

- Yang, M.; Du, K.; Hou, Y.; Xie, S.; Dong, Y.; Li, D.; Du, Y. Synergistic antifungal effect of amphotericin B-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles and ultrasound against Candida albicans biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02022-18.