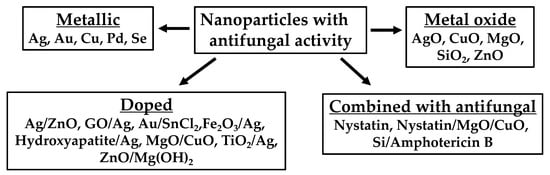

Fungi were initially included as a part of Kingdom Plantae but in 1969 were grouped into Kingdom Fungi, which comprises diverse groups with different morphologies, such as unicellular yeasts and multicellular organisms. The rate of antifungal resistance development has been called “unprecedented”. This is because immunocompromised individuals are at a higher risk of fungal infections than healthy individuals. Moreover, medical advancements over the past few decades and the HIV epidemic have increased the number of immunocompromised people, which has, in turn, shifted fungal infections from being an infrequent cause of disease to being an important contributor to human morbidity and mortality worldwide. There are six antifungal drug classes, and this scarcity, combined with the increasing resistance, has led to the need for novel treatments. The appearance of resistant species of fungi to the existent antimycotics is challenging for the scientific community. One emergent technology is the application of nanotechnology to develop novel antifungal agents. Metal nanoparticles (NPs) have shown promising results as an alternative to classical antimycotics.

- nanoparticles

- metals

- ROS

1. Nanoparticle Formulation as Antifungal Agents

| Type of NP | Shape | Size (nm) | Organism(s) Tested | MIC100 (µg/mL) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | Spherical | 3 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae (KCTC 7296) Trichosporon beigelii (KCTC 7707) Candida albicans (ATCC 90028) |

2 | [55] |

| Spherical | 1–21 | Candida albicans Candida glabrata Candida parapsilosis Candida tropicalis Fusarium solani Fusarium moniliforme Fusarium oxysporum Aspergillus flavus Aspergillus fumigatus Aspergillus terrus Sporothrix schenckii Cryptococcus neoformans |

0.25 0.125 0.25 0.125 1 2 4 1 2 2 0.25 0.25 |

[56] | |

| Spherical | 5 | Candida albicans (324LA/84) Candida glabrata (ATCC 90030) Candida albicans (ATCC 10321) Candida glabrata (D1) |

0.4–0.8 0.4–0.8 0.8–1.6 1.6–3.3 |

[57] | |

| Spherical | 7 | Aspergillus flavus Aspergillus fumigatus |

100 100 |

[58] | |

| Spherical | 25 | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida parapsilosis Candida tropicalis |

0.42 0.21 1.690 0.840 |

[59] | |

| Spherical | 5–20 | Trichosporon asahii (CBS2479) Trichosporon asahii (BZ701) Trichosporon asahii (BZ702) Trichosporon asahii (BZ703) Trichosporon asahii (BZ704) Trichosporon asahii (BZ705) Trichosporon asahii (BZ705R) Trichosporon asahii (BZ901) Trichosporon asahii (BZ902) Trichosporon asahii (BZ121) Trichosporon asahii (BZ122) Trichosporon asahii (BZ123) Trichosporon asahii (BZ124) Trichosporon asahii (BZ125) Trichosporon asahii (CBS8904) Trichosporon asahii (CBS7137) Trichosporon asahii (CBS8520) |

0.50 0.67 0.50 1.00 0.67 0.50 0.50 0.67 1.00 0.83 0.67 0.50 0.67 0.83 0.50 0.67 0.67 |

[60] | |

| Spherical | 15–25 | Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) Candida albicans (ATCC 90028) Candida glabrata (ATCC 90030) Candida parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) |

1.56 6.25 3.12 6.25 |

[61] | |

| Spherical | 25 | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida parapsilosis Candida tropicalis |

27 27 27 27 |

[59] | |

| Spherical to polyhedric | 73.72 | Trichophyton rubrum (n = 8) Trichophyton rubrum (ATCC MYA 4438) |

0.5–2.5 <0.25 |

[62] | |

| Spherical | 76.14 | Trichophyton rubrum (n = 8) Trichophyton rubrum (ATCC MYA 4438) |

>7.5 >7.5 |

[62] | |

| Spherical | 100.6 | Trichophyton rubrum (n = 8) Trichophyton rubrum (ATCC MYA 4438) |

0.5–5 0.5 |

[62] | |

| NR | NR | Fusarium graminearum | 4.68 | [63] | |

| NR | NR | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida parapsilosis Candida tropicalis |

0.42 0.21 1.69 0.84 |

[59] | |

| NR | NR | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida parapsilosis Candida tropicalis |

0.052 0.1 0.84 0.42 |

[59] | |

| NR | NR | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida parapsilosis Candida tropicalis |

3.38 3.38 3.38 3.38 |

[59] | |

| NR | 20–25 | Aspergillus niger Candida albicans Cryptococcus neoformans |

25 6 3 |

[64] | |

| NR | NR | Fusarium graminearum | 12.5 | [63] | |

| Ag/ZnO | Spherical | 7/477 | Aspergillus flavus Aspergillus fumigatus |

50/10 50/10 |

[58] |

| qAg | Spherical | 2–3 | Candida albicans | 0.07 | [65] |

| Cu | Spherical | 10–40 | Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) Candida albicans (Clinical strain C) Candida albicans (Clinical strain E) |

129.7 1037.5 518.8 |

[66] |

| Wires | 20–30 µm, 30–60 nm diameter | Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) Candida albicans (Clinical strain C) Candida albicans (Clinical strain E) |

260.3 260.3 260.3 |

[66] | |

| γ-Fe2O3/Ag | NR | 20–40 (Ag) + 5 (γ-Fe2O3) | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida tropicalis (5) Candida parapsilosis (6) |

1.9 1.9 31.3 31.3 |

[67] |

| Fe3O4/Ag | NR | ~5 (Ag) + ~70 (Fe3O4) | Candida albicans (I) Candida albicans (II) Candida tropicalis (5) Candida parapsilosis (6) |

1.9 1.9 3.9 7.8 |

[67] |

| GO/Ag | Spherical | 10–35 | Fusarium graminearum | 9.37 | [63] |

| HA/Ag | Rod/Spherical | 12–27 | Candida albicans | 62.5 | [68] |

| MgO 500 °C calcination |

Flaked layers | 52 ± 18 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

156 312 |

[69] |

| MgO 1000 °C calcination |

Flaked layers | 96 ± 33 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[69] |

| Pd | Spherical | 9 ± 3.9 | Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) Aspergillus niger |

212.5 200 |

[70] |

| Se | Spherical | 80–200 | Candida albicans (ATCC 76615) Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) |

100 70 |

[71] |

| Se | Spherical | 37–46 | Aspergillus fumigatus (TIMML-025) Aspergillus fumigatus (TIMML-050) Aspergillus fumigatus (TIMML-379) |

0.5 0.5 1 |

[72] |

| Silica/AmB | NR | 5 | Candida albicans Candida krusei Candida parapsilosis Candida glabrata Candida tropicalis |

100 1000 1000–2000 300 100 |

[73] |

| TiO2/Ag + NaHB4 | NR | 250–300 | Aspergillus niger Candida albicans Cryptococcus neoformans |

25 12.5 12.5 |

[64] |

| TiO2/Ag + UV | NR | 250–300 | Aspergillus niger Candida albicans Cryptococcus neoformans |

12.5 6 3 |

[64] |

| ZnO | Spherical | 20–40 | Candida albicans (n = 125) | 0.2–296 | [74] |

| Spherical | 477 | Aspergillus flavus Aspergillus fumigatus |

20 20 |

[58] | |

| ZnO 500 °C calcination |

Spherical + cylindrical | 51 ± 13 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

156 312 |

[69] |

| ZnO 1000 °C calcination |

Hexagonal bars | 53 ± 17 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

156 312 |

[69] |

| ZnO/Mg(OH)2 25 °C synthesis |

Flakes + bars | 54 ± 17 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

156 312 |

[69] |

| ZnO NP 25 °C synthesis |

Hexagonal bars + ovoidal | 63 ± 18 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[69] |

| ZnO/Mg(OH)2 70 °C synthesis |

Flakes + bars | 71 ± 22 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[69] |

| ZnO 25 °C synthesis, hydrothermal |

Prisms with pyramidal ends | 77 ± 31 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[69] |

| ZnO/Mg(OH)2 NP 25 °C synthesis, hydrothermal 160 °C |

Flakes + bars | 88 ± 30 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[69] |

| ZnO/Mg(OH)2 70 °C synthesis, hydrothermal 160 °C |

Flakes + bars | 98 ± 41 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[69] |

| ZnO/MgO 25 °C synthesis, 500 °C calcination |

Flakes | 139 ± 49 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[69] |

| ZnO/MgO 70 °C synthesis, 500 °C calcination |

Flakes | 161 ± 44 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

312 312 |

[69] |

| ZnO/MgO 70 °C synthesis, 1000 °C calcination |

Flakes | 219 ± 39 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from papaya) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (from avocado) |

625 625 |

[69] |

| ZnO | NR | NR | Candida albicans (n = 10) | 0.02–269 | [75] |

| Type of NP | Shape | Size (nm) | Organism(s) Tested | MIC50 (µg/mL) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | Spherical | 30–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

4 9 9 |

[76] |

| Ag | Cubical | 40–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

1 7 7 |

[76] |

| Ag | Wires | 250–300 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

5 12 11 |

[76] |

| Au | Cubical | 30–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

3 10 11 |

[76] |

| Au | Spherical | 35–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

8 13 12 |

[76] |

| Au | Wires | 300–500 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

7 15 15 |

[76] |

| ZnO | Spherical | 20–40 | Candida albicans (n = 125) | 8.2 | [74] |

| ZnO | NR | NR | Candida albicans (n = 10) | 5 | [75] |

| Type of NP | Shape | Size (nm) | Organism(s) Tested | MIC80 (µg/mL) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AuNP + SnCl2 as reducing agent | Polygonal, almost spherical | 5–50 | Candida albicans Candida tropicalis Candida glabrata |

16 16 16 |

[77] |

| AuNP + NaBH4 as reducing agent | Spherical | 3–20 | Candida albicans Candida tropicalis Candida glabrata |

4 4 4 |

[77] |

| Type of NP | Shape | Size (nm) | Organism(s) Tested | MIC90 (µg/mL) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMW Chitosan NP ± 1 mg/mL chitosan | Spherical | 174 ± 38.47 | Candida albicans Fusarium solani Aspergillus niger |

250 1000 NR |

[78] |

| HMW Chitosan NP ± 1 mg/mL chitosan | Spherical | 210 ± 24.54 | Candida albicans Fusarium solani Aspergillus niger |

1000 500 NR |

[78] |

| LMW Chitosan NP ± 2 mg/mL chitosan | Spherical | 233 ± 41.38 | Candida albicans Fusarium solani Aspergillus niger |

857.2 857.2 NR |

[78] |

| HMW Chitosan NP ± 2 mg/mL chitosan | Spherical | 263 ± 86.44 | Candida albicans Fusarium solani Aspergillus niger |

857.2 857.2 1714 |

[78] |

| LMW Chitosan NP ± 3 mg/mL chitosan | Spherical | 255 ± 42.81 | Candida albicans Fusarium solani Aspergillus niger |

607.2 1214 NR |

[78] |

| HMW Chitosan NP ± 3 mg/mL chitosan | Spherical | 301 ± 72.85 | Candida albicans Fusarium solani Aspergillus niger |

607.2 1214.3 2428.6 |

[78] |

| Ag | Cubical | 40–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

8 30 31 |

[76] |

| Ag | Spherical | 30–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

11 37 35 |

[76] |

| Ag | Wires | 250–300 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

21 51 48 |

[76] |

| Au | Cubical | 30–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

10 45 46 |

[76] |

| Au | Spherical | 35–50 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

15 47 48 |

[76] |

| Au | Wires | 300–500 | Candida albicans (n = 30) Candida glabrata (n = 30) Candida tropicalis (n = 30) |

30 70 73 |

[76] |

| ZnO | Spherical | 20–40 | Candida albicans (n = 125) | 17.76 | [74] |

| ZnO | NR | NR | Candida albicans (n = 10) | 11.3 |

| Type of NP | Shape | Size (nm) | Organism(s) Tested | Activity (mm) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuO | Spherical | 3–30 | Fusarium equiseti Fusarium oxysporum Fusarium culmorum |

25 20 19 |

[79] |

| Pd | Spherical | 200 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | Day 2: 3.6 Day 4: 1.6 |

[80] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Day 2: 12.2 Day 4: 10.9 |

||||

| Pd | Spherical | 220 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | Day 2: 7.9 Day 4: 6.3 |

[80] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Day 2: 5.1 Day 4: 4.7 |

||||

| Pd | Spherical | 250 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | Day 2: 2.4 Day 4: 0.7 |

[80] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Day 2: 10.4 Day 4: 9.6 |

||||

| Pd | Spherical | 350 | Fusarium oxysporum | Day 2: 1.5 Day 4: 1.3 |

[80] |

| Pd | Spherical | 550 | Fusarium oxysporum | Day 2: 3.8 Day 4: 3.3 |

[80] |

| Nystatin/MgO/CuO | Spherical | 8000–10000 | Candida albicans (AH201) Candida albicans (AH267) |

24.5 ± 1.7 14.3 ± 1.2 |

[81] |

| Nystatin | Spherical | 8000–10000 | Candida albicans (AH201) Candida albicans (AH267) |

0.41 ± 0.23 0.5 ± 0.21 |

[81] |

| MgO/CuO | Spherical | 8000–10000 | Candida albicans (AH201) Candida albicans (AH267) |

19.2 ± 1.6 1.3 ± 0.61 |

[81] |

| TiO2/BPE B | NR | NR | Candida albicans (ATCC 14053) | 11.2 ± 0.02 | [82] |

| TiO2/BPE C | NR | NR | Candida albicans (ATCC 14053) | 15.9 ± 0.04 | [82] |

| TiO2/BPE D | NR | NR | Candida albicans (ATCC 14053) | 13.5 ± 0.04 | [82] |

| TiO2/BPE E | NR | NR | Candida albicans (ATCC 14053) | 14.6 ± 0.01 | [82] |

| TiO2/BPE B | NR | NR | Penicillum chrysogenum (MTCC 5108) | 10.2 ± 0.05 | [82] |

| TiO2/BPE C | NR | NR | Penicillum chrysogenum (MTCC 5108) | 18.0 ± 0.03 | [82] |

| TiO2/BPE D | NR | NR | Penicillum chrysogenum (MTCC 5108) | 15.0 ± 0.04 | [82] |

| TiO2/BPE E | NR | NR | Penicillum chrysogenum (MTCC 5108) | 13.5 ± 0.08 | [82] |

| Type of NP | Shape | Size (nm) | Organism(s) Tested | Activity (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | NR | 20–100 | Cladosporium cladosporioides Aspergillus niger |

50 µg/mL → 90 50 µg/mL → 70 |

[83] |

| Ag | Polygonal | 35 ± 15 | Candida tropicalis Saccharomyces boulardii |

25 µg/mL → >95 50 µg/mL → >95 25 µg/mL → <50 50 µg/mL → >95 |

[84] |

| Ag | Spherical | 5 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | 13 µg/mL → 73 26 µg/mL → 82 56 µg/mL → 89 |

[85] |

| Ag | Spherical | 24 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | 13 µg/mL → 74 26 µg/mL → 82 56 µg/mL → 89 |

[85] |

| ZnO | Spherical | 30–45 | Erythricium salmonicolor | 12 mmol/L, day 7 → 71.3 12 mmol/L, day 10 → 51.1 9 mmol/L, day 7 → 58.3 9 mmol/L, day 10 → 44.6 6 mmol/L, day 7 → 48.9 6 mmol/L, day 10 → 23.6 3 mmol/L, day 7 → 36.9 3 mmol/L, day 10 → 14.1 |

[86] |

| Ag | NR | NR | Rhizoctonia solani (AG1) Rhizoctonia solani (AG4) Macrophomina phaseolina Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Trichoderma harzianum Pythium aphanidermatum |

6 µg/mL → 75 8 µg/mL → 80 10 µg/mL → 90 12 µg/mL → 90 14 µg/mL → 90 16 µg/mL → 100 6 µg/mL → ≥90 8 µg/mL → ≥90 10 µg/mL → ≥90 12 µg/mL → 100 14 µg/mL → 100 16 µg/mL → 100 6 µg/mL → 100 8 µg/mL → 100 10 µg/mL → 100 12 µg/mL → 100 14 µg/mL → 100 16 µg/mL → 100 6 µg/mL → ≥95 8 µg/mL → 100 10 µg/mL → 100 12 µg/mL → 100 14 µg/mL → 100 16 µg/mL → 100 6 µg/mL → 80 8 µg/mL → 84 10 µg/mL → 90 12 µg/mL → 100 14 µg/mL → 100 16 µg/mL → 100 6 µg/mL → 100 8 µg/mL → 100 10 µg/mL → 100 12 µg/mL → 100 14 µg/mL → 100 16 µg/mL → 100 |

[87] |

| Ag | Spherical | 10–20 | Bipolaris sorokiniana | ≥2 µg/mL → 100 | [88] |

| Ag | Spherical | 1–9 | Aspergillus flavus | 5 µg/mL → 0 15 µg/mL → 30 25 µg/mL → 58 35 µg/mL → 85 45 µg/mL → 98 60 µg/mL → 100 |

[89] |

| PEI1/Ag | Spherical | 20.6 | Rhizopus arrhizus | 1.6 µg/mL → 97 | [90] |

| PEI2/Ag | Spherical | 4.24 | 6.5 µg/mL → 94 | ||

| SiO2 | Spherical | 9.92–19.8 | Rhizoctonia solani | 100 µg/mL → 93–100 | [91] |

2. Antifungal Classes and Combination with NPs

| Class | Examples | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Allylamines | Terbinafine Naftifine |

Squalene epoxidase inhibition, responsible for conversion of squalene to ergosterol |

| Azoles | Clotrimazole Miconazole Ketoconazole Fluconazole Itrazonacole |

C14-α demethylation inhibition of lanosterol, inhibiting ergosterol synthesis |

| Echinocandins | Caspofungin Micafungin Anidulafungin |

β-(1,3)-D-glucan synthase inhibition, interfering with cell wall synthesis |

| Polyenes | Amphotericin B Nystatin Candicidin |

Ergosterol binding, forming pores and causing leakage, inhibiting proper transport mechanisms |

| Antimetabolites | Flucytosine | Pyrimidine analogue, interfering with nucleic acid synthesis |

| Triterpenoids | Ibrexafungerp | β-(1,3)-D-glucan synthase inhibition, interfering with cell wall synthesis |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nano12244470