Video Upload Options

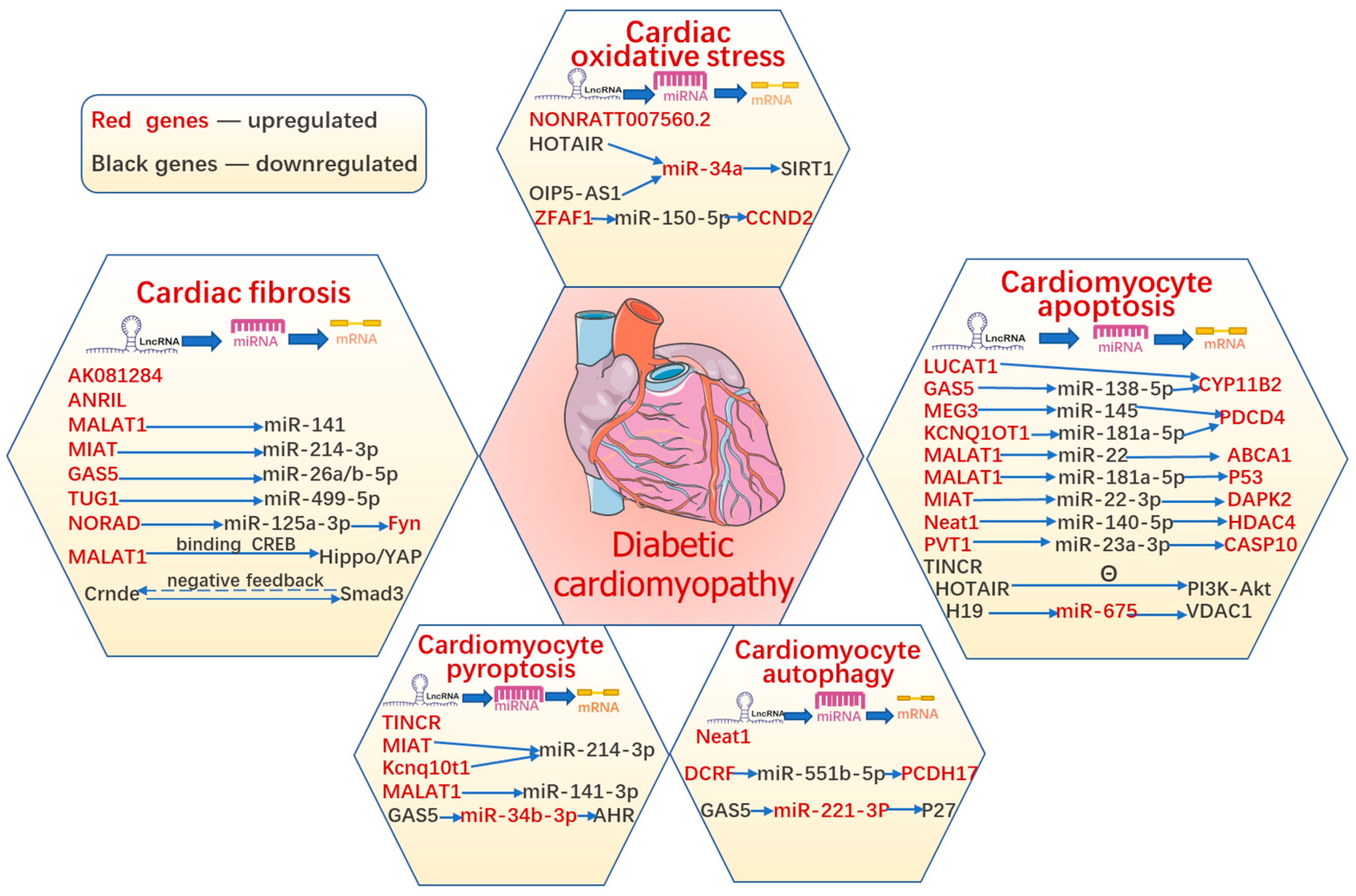

Diabetes mellitus is a burdensome public health problem. Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a major cause of mortality and morbidity in diabetes patients. The pathogenesis of DCM is multifactorial and involves metabolic abnormalities, the accumulation of advanced glycation end products, myocardial cell death, oxidative stress, inflammation, microangiopathy, and cardiac fibrosis. Evidence suggests that various types of cardiomyocyte death act simultaneously as terminal pathways in DCM. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of RNA transcripts with lengths greater than 200 nucleotides and no apparent coding potential. Emerging studies have shown the critical role of lncRNAs in the pathogenesis of DCM, along with the development of molecular biology technologies.

1. Introduction

2. Role of lncRNAs in Various Types of Cardiomyocyte Death in DCM

3. Role of lncRNAs in Oxidative Stress in DCM

4. Role of lncRNAs in Diabetes-Induced Cardiac Fibrosis

| LncRNAs | Experimental Model | Target Genes | Expression | Mechanism Involved | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Stress | |||||

| NONRATT007560.2 | HG-treated primary culture of neonatal cardiomyocytes | upregulated | inhibition of NONRATT007560.2 abated the formation of ROS | [19] | |

| HOTAIR | STZ-induced diabetic rat model and HG-treated H9c2 cells | miR-34a | downregulated | HOTAIR protected against DCM via activation of the SIRT1 expression by sponging miR-34a |

[22] |

| OIP5-AS1 | HG-treated H9c2 cells | miR-34a | downregulated | OIP5-AS1 overexpression promoted viability and inhibits high glucose-induced oxidative stress of cardiomyocytes by targeting miRNA-34a/SIRT1 Axis | [23] |

| ZFAS1 | STZ-induced diabetic mouse model and primary culture of neonatal cardiomyocytes | miR-150-5p | upregulated | inhibition of ZFAS1 attenuated ferroptosis by sponging miR-150-5p and activating CCND2 against DCM | [26] |

| Cardiac Fibrosis | |||||

| ZFAS1 | STZ-induced diabetic mouse model and primary culture of neonatal cardiomyocytes | miR-150-5p | upregulated | inhibition of ZFAS1 attenuated ferroptosis by sponging miR-150-5p and activating CCND2 against DCM | |

| MALAT1 | STZ-induced diabetic mice model and HG-treated primary culture of neonatal CFs | miR-141 | upregulated | melatonin alleviated cardiac fibrosis via inhibiting MALAT1/miR-141-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome and TGF-β1/Smads signaling | [34] |

| Crnde | human myocardial biopsies, STZ-induced diabetic mice model, and HG-treated primary culture of neonatal CFs | downregulated | lncRNA Crnde attenuated cardiac fibrosis via Smad3-Crnde negative feedback | [35] | |

| MIAT | Human serum samples, STZ-induced diabetic mice model, and HG-treated primary culture of neonatal CFs | miR-214-3p | upregulated | MIAT inhibited IL-17 production and alleviated the onset of cardiac fibrosis via specific attenuating miR-214-3p | [39] |

| AK081284 | STZ-induced diabetic mice model and HG-treated primary culture of neonatal CFs | upregulated | AK081284 knockdown inhibited the production of collagen I, collagen III, TGFβ1 and α-SMA stimulated by IL-17 | [41] | |

| ANRIL | STZ-induced diabetic mice model | upregulated | ANRIL upregulated production of ECM proteins and VEGF via epigenetic upregulating p300 and EZH2 | [44] | |

| MALAT1 | STZ-induced diabetic mice model and neonatal mouse HG-treated CFs | CREB | upregulated | MALAT1 regulated diabetic cardiac fibroblasts through the Hippo/YAP signaling pathway by binding CREB | [49] |

| TUG1 | STZ-induced diabetic mice model and HG-treated cardiomyocytes | miR-499-5p | upregulated | inhibition of TUG1 protected against DCM-induced diastolic dysfunction by regulating miR-499-5p | [50] |

| NORAD | subcutaneous injection of angiotensin II (ATII) in db/db mice and HG-treated primary mouse cardiomyocytes | miR-125a-3p/Fyn | upregulated | silencing NORAD mitigated fibrosis and inflammatory responses via the ceRNA network of NORAD/miR-125a-3p/Fyn | [51] |

| GAS5 | STZ-induced diabetic mice model and HG-treated primary culture of neonatal cardiomyocytes | miR-26a/b-5p | upregulated | silencing GAS5 alleviated apoptosis and fibrosis by targeting miR-26a/b-5p | [52] |

References

- Jia, G.; Hill, M.A.; Sowers, J.R. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: An Update of Mechanisms Contributing to This Clinical Entity. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 624–638.

- Pant, T.; Dhanasekaran, A.; Fang, J.; Bai, X.; Bosnjak, Z.J.; Liang, M.; Ge, Z.-D. Current status and strategies of long noncoding RNA research for diabetic cardiomyopathy. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2018, 18, 197.

- Haffner, S.M.; Lehto, S.; Rönnemaa, T.; Pyörälä, K.; Laakso, M. Mortality from Coronary Heart Disease in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes and in Nondiabetic Subjects with and without Prior Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 229–234.

- Zhang, W.; Xu, W.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, X. Non-coding RNA involvement in the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 5859–5867.

- Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Lv, J. Endothelial Dysfunction and Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 851941.

- Jia, G.; DeMarco, V.; Sowers, J.R. Insulin Resistance and Hyperinsulinaemia in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 12, 144–153.

- Tan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, C.; Wintergerst, K.A.; Keller, B.B.; Cai, L. Mechanisms of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy and Potential Therapeutic Strategies: Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 585–607.

- Kopp, F.; Mendell, J.T. Functional Classification and Experimental Dissection of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell 2018, 172, 393–407.

- Kapranov, P.; Cheng, J.; Dike, S.; Nix, D.A.; Duttagupta, R.; Willingham, A.T.; Stadler, P.F.; Hertel, J.; Hackermüller, J.; Hofacker, I.L.; et al. RNA Maps Reveal New RNA Classes and a Possible Function for Pervasive Transcription. Science 2007, 316, 1484–1488.

- Panchapakesan, U.; Pollock, C. Long Non-Coding Rnas-Towards Precision Medicine in Diabetic Kidney Disease? Clin. Sci. 2016, 130, 1599–1602.

- Dechamethakun, S.; Muramatsu, M. Long noncoding RNA variations in cardiometabolic diseases. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 62, 97–104.

- Li, F.; Wen, X.; Zhang, H.; Fan, X. Novel Insights into the Role of Long Noncoding RNA in Ocular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 478.

- Shen, G.X. Oxidative Stress and Diabetic Cardiovascular Disorders: Roles of Mitochondria and Nadph Oxidase. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2010, 88, 241–248.

- Li, W.; Li, W.; Leng, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Xia, Z. Ferroptosis Is Involved in Diabetes Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury Through Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. DNA Cell Biol. 2020, 39, 210–225.

- Byrne, N.J.; Rajasekaran, N.S.; Abel, E.D.; Bugger, H. Therapeutic potential of targeting oxidative stress in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 169, 317–342.

- De Blasio, M.J.; Huynh, K.; Qin, C.; Rosli, S.; Kiriazis, H.; Ayer, A.; Cemerlang, N.; Stocker, R.; Du, X.-J.; McMullen, J.R.; et al. Therapeutic targeting of oxidative stress with coenzyme Q10 counteracts exaggerated diabetic cardiomyopathy in a mouse model of diabetes with diminished PI3K(p110α) signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 87, 137–147.

- Huynh, K.; Kiriazis, H.; Du, X.-J.; Love, J.E.; Gray, S.P.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K.A.; McMullen, J.R.; Ritchie, R.H. Targeting the upregulation of reactive oxygen species subsequent to hyperglycemia prevents type 1 diabetic cardiomyopathy in mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 60, 307–317.

- Ye, G.; Metreveli, N.S.; Donthi, R.V.; Xia, S.; Xu, M.; Carlson, E.C.; Epstein, P.N. Catalase Protects Cardiomyocyte Function in Models of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2004, 53, 1336–1343.

- Yu, M.; Shan, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Cao, Q.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhao, X. RNA-Seq analysis and functional characterization revealed lncRNA NONRATT007560.2 regulated cardiomyocytes oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by high glucose. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 18278–18287.

- Karbasforooshan, H.; Karimi, G. The Role of Sirt1 in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 90, 386–392.

- Guo, R.; Liu, W.; Liu, B.; Zhang, B.; Li, W.; Xu, Y. SIRT1 suppresses cardiomyocyte apoptosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy: An insight into endoplasmic reticulum stress response mechanism. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 191, 36–45.

- Gao, L.; Wang, X.; Guo, S.; Xiao, L.; Liang, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yao, R.; Liu, Y.; et al. LncRNA HOTAIR functions as a competing endogenous RNA to upregulate SIRT1 by sponging miR-34a in diabetic cardiomyopathy. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 4944–4958.

- Sun, H.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, X. Long Noncoding RNA OIP5-AS1 Overexpression Promotes Viability and Inhibits High Glucose-Induced Oxidative Stress of Cardiomyocytes by Targeting MicroRNA-34a/SIRT1 Axis in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. -Drug Targets 2021, 21, 2017–2027.

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent Form of Nonapoptotic Cell Death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072.

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, W.; Men, H.; Bao, T.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Tan, Y.; Keller, B.B.; Tong, Q.; et al. Ferroptosis is essential for diabetic cardiomyopathy and is prevented by sulforaphane via AMPK/NRF2 pathways. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 708–722.

- Ni, T.; Huang, X.; Pan, S.; Lu, Z. Inhibition of the long non-coding RNA ZFAS1 attenuates ferroptosis by sponging miR-150-5p and activates CCND2 against diabetic cardiomyopathy. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 9995–10007.

- Huynh, K.; Bernardo, B.C.; McMullen, J.R.; Ritchie, R.H. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: Mechanisms and new treatment strategies targeting antioxidant signaling pathways. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 142, 375–415.

- Li, J.H.; Huang, X.R.; Zhu, H.J.; Johnson, R.; Lan, H.Y. Role of Tgf-Beta Signaling in Extracellular Matrix Production under High Glucose Conditions. Kidney Int. 2003, 63, 2010–2019.

- Russo, I.; Frangogiannis, N.G. Diabetes-Associated Cardiac Fibrosis: Cellular Effectors, Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016, 90, 84–93.

- Zhao, J.; Randive, R.; Stewart, J.A. Molecular mechanisms of AGE/RAGE-mediated fibrosis in the diabetic heart. World J. Diabetes 2014, 5, 860–867.

- Frangogiannis, N.G. Cardiac Fibrosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 1450–1488.

- Bujak, M.; Ren, G.; Kweon, H.J.; Dobaczewski, M.; Reddy, A.; Taffet, G.; Wang, X.-F.; Frangogiannis, N. Essential Role of Smad3 in Infarct Healing and in the Pathogenesis of Cardiac Remodeling. Circulation 2007, 116, 2127–2138.

- Chen, X.; Liu, G.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Y.; Dong, W.; Liang, E.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M. Inhibition of Mef2a Prevents Hyperglycemia-Induced Extracellular Matrix Accumulation by Blocking Akt and Tgf-Β1/Smad Activation in Cardiac Fibroblasts. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2015, 69, 52–61.

- Che, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Sahil, A.; Lv, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Dong, R.; Xue, H.; et al. Melatonin Alleviates Cardiac Fibrosis Via Inhibiting Lncrna Malat1/Mir-141-Mediated Nlrp3 Inflammasome and Tgf-Beta1/Smads Signaling in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2020, 34, 5282–5298.

- Zheng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Guan, J.; Xu, L.; Xiao, W.; Zhong, Q.; Ren, C.; Lu, J.; Liang, J.; et al. Long noncoding RNA Crnde attenuates cardiac fibrosis via Smad3-Crnde negative feedback in diabetic cardiomyopathy. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 1645–1655.

- Wu, K.K. Control of Tissue Fibrosis by 5-Methoxytryptophan, an Innate Anti-Inflammatory Metabolite. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 759199.

- Yoon, S.; Kang, G.; Eom, G.H. HDAC Inhibitors: Therapeutic Potential in Fibrosis-Associated Human Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1329.

- Zhang, X.; Qu, H.; Yang, T.; Kong, X.; Zhou, H. Regulation and functions of NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiac fibrosis: Current knowledge and clinical significance. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112219.

- Qi, Y.; Wu, H.; Mai, C.; Lin, H.; Shen, J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Mao, Y.; Xie, X. Lncrna-Miat-Mediated Mir-214-3p Silencing Is Responsible for Il-17 Production and Cardiac Fibrosis in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 243.

- Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, P.; Cui, W.; Hao, J.; Ma, X.; Yin, Z.; Du, J. Γδt Cell-Derived Interleukin-17a Via an Interleukin-1β-Dependent Mechanism Mediates Cardiac Injury and Fibrosis in Hypertension. Hypertension 2014, 64, 305–314.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Li, T.-T.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, X.-X.; Xue, G.-L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.-F.; et al. Ablation of interleukin-17 alleviated cardiac interstitial fibrosis and improved cardiac function via inhibiting long non-coding RNA-AK081284 in diabetic mice. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018, 115, 64–72.

- Ricciardi, C.A.; Gnudi, L. Vascular growth factors as potential new treatment in cardiorenal syndrome in diabetes. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 51, e13579.

- Yap, K.L.; Li, S.; Muñoz-Cabello, A.M.; Raguz, S.; Zeng, L.; Mujtaba, S.; Gil, J.; Walsh, M.J.; Zhou, M.-M. Molecular Interplay of the Noncoding RNA ANRIL and Methylated Histone H3 Lysine 27 by Polycomb CBX7 in Transcriptional Silencing of INK4a. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 662–674.

- Thomas, A.A.; Feng, B.; Chakrabarti, S. ANRIL regulates production of extracellular matrix proteins and vasoactive factors in diabetic complications. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2018, 314, E191–E200.

- Ma, S.; Meng, Z.; Chen, R.; Guan, K.L. The Hippo Pathway: Biology and Pathophysiology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88, 577–604.

- Szeto, S.G.; Narimatsu, M.; Lu, M.; He, X.; Sidiqi, A.M.; Tolosa, M.F.; Chan, L.; De Freitas, K.; Bialik, J.F.; Majumder, S.; et al. YAP/TAZ Are Mechanoregulators of TGF-β-Smad Signaling and Renal Fibrogenesis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 3117–3128.

- Xiao, Y.; Hill, M.C.; Li, L.; Deshmukh, V.; Martin, T.J.; Wang, J.; Martin, J.F. Hippo pathway deletion in adult resting cardiac fibroblasts initiates a cell state transition with spontaneous and self-sustaining fibrosis. Genes Dev. 2019, 33, 1491–1505.

- Byun, J.; Del Re, D.P.; Zhai, P.; Ikeda, S.; Shirakabe, A.; Mizushima, W.; Miyamoto, S.; Brown, J.H.; Sadoshima, J. Yes-associated protein (YAP) mediates adaptive cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 3603–3617.

- Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Zhan, X. LncRNA MALAT1 regulates diabetic cardiac fibroblasts through the Hippo–YAP signaling pathway. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2020, 98, 537–547.

- Zhao, L.; Li, W.; Zhao, H. Inhibition of Long Non-Coding RNA Tug1 Protects against Diabetic Cardiomyopathy Induced Diastolic Dysfunction by Regulating Mir-499-5p. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2020, 12, 718–730.

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Li, X. Norad Lentivirus Shrna Mitigates Fibrosis and Inflammatory Responses in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy Via the Cerna Network of Norad/Mir-125a-3p/Fyn. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 70, 1113–1127.

- Zhu, C.; Zhang, H.; Wei, D.; Sun, Z. Silencing Lncrna Gas5 Alleviates Apoptosis and Fibrosis in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy by Targeting Mir-26a/B-5p. Acta Diabetol. 2021, 58, 1491–1501.