| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lianchun Wang | -- | 3029 | 2022-12-08 17:02:26 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 3029 | 2022-12-09 02:30:30 | | |

Video Upload Options

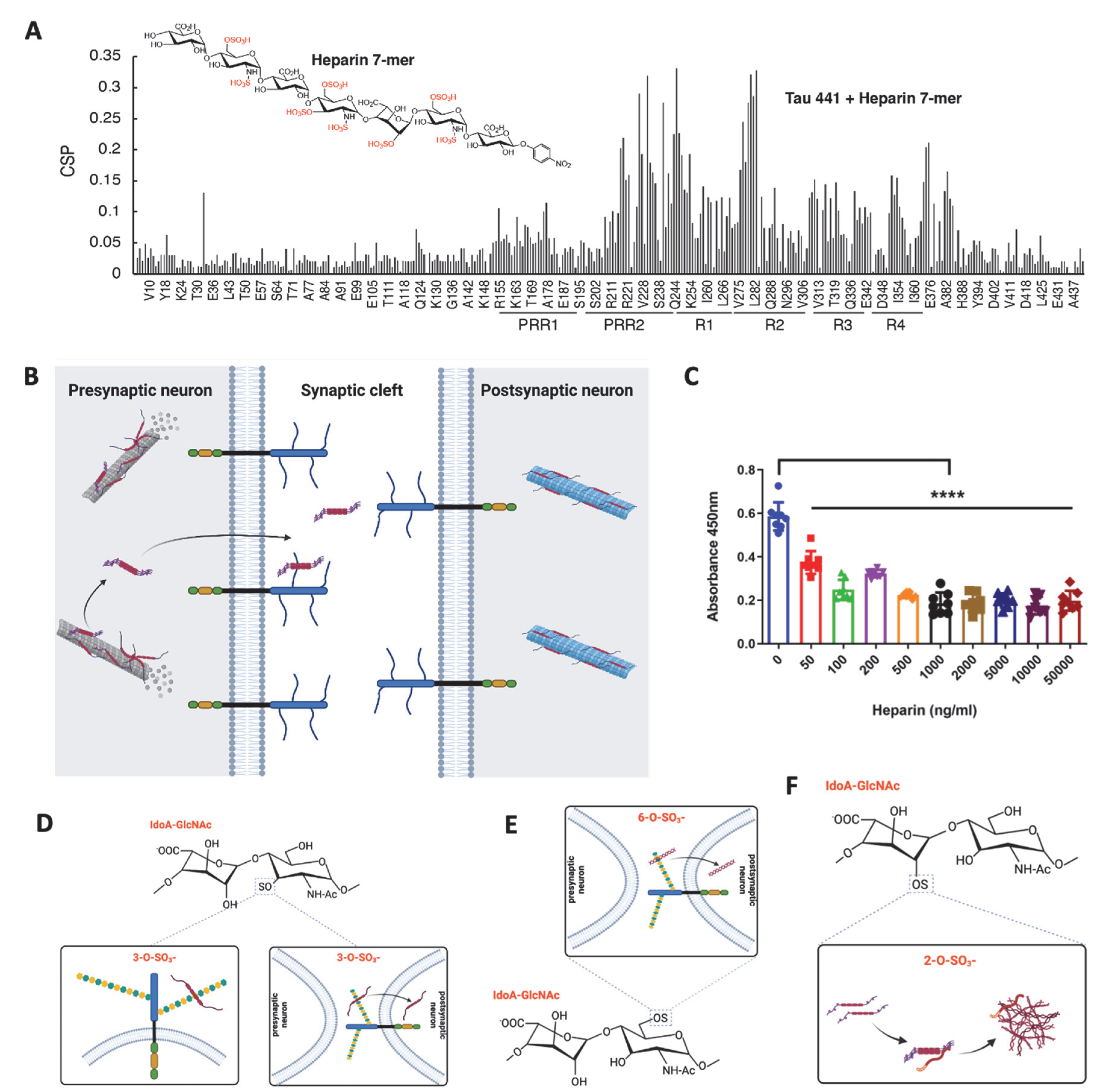

Tauopathies are a class of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, and are characterized by intraneuronal tau inclusion in the brain and the patient’s cognitive decline with obscure pathogenesis. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans, a major type of extracellular matrix, have been believed to involve in tauopathies. The heparan sulfate proteoglycans co-deposit with tau in Alzheimer’s patient brain, directly bind to tau and modulate tau secretion, internalization, and aggregation.

1. Introduction

2. The Tau Protein

3. Tau in Physiological States

4. Tau in Pathological States

5. Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans

6. Heparan Sulfate-Tau Interaction: The Related Structures

7. The Role of Heparan Sulfate in the Tau-Mediated Pathological Process

7.1. HS in Tau Secretion

7.2. HS in Tau Cell Surface Binding

7.3. HS in Tau Internalization

7.4. HS in Tau Aggregation

8. Aberrant HSPG Expression in AD and Other Tauopathies

|

Clinical Diagnosis |

Predominant Tau Isoforms |

Human Brain Samples |

GAGs/Gene Expression in Disease |

GAGs Function in Disease |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AD |

3R + 4R Tau |

7 AD vs. 4 control |

HS ↑ |

N/A |

[41] |

|

AD |

3R + 4R Tau |

N/A |

N/A |

Helicity of PHFs changed (potential) |

[65] |

|

AD |

3R + 4R Tau |

25 AD vs. 10 control |

HS ↑ |

N/A |

[77] |

|

AD |

3R + 4R Tau |

20 AD vs. 20 control |

Sulf1 -; Sulf2 ↓ |

N/A |

[79] |

|

AD |

3R + 4R Tau |

5 AD vs. 5 control |

HS ↑; Ndst2 ↑; Hs3st2 ↑; Hs3st4 ↑; Glce ↑; HPSE ↑ |

HS-tau binding capacity ↑ |

[34] |

|

AD |

3R + 4R Tau |

18 AD vs. 6 control |

Altered expression of multiple HS biosynthesis/remodeling genes |

N/A |

[80] |

|

AD |

3R + 4R Tau |

5 AD vs. 5 control |

HS ↑; 3-o-sulfation ↑ |

N/A |

[78] |

References

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, K.M.; Yang, L.; Dong, Q.; Yu, J.T. Tauopathies: New perspectives and challenges. Mol. Neurodegener. 2022, 17, 28.

- Wang, Y.; Mandelkow, E. Tau in physiology and pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 5–21.

- Gotz, J.; Halliday, G.; Nisbet, R.M. Molecular Pathogenesis of the Tauopathies. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2019, 14, 239–261.

- Ittner, A.; Ittner, L.M. Dendritic Tau in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron. 2018, 99, 13–27.

- Drubin, D.G.; Caput, D.; Kirschner, M.W. Studies on the expression of the microtubule-associated protein, tau, during mouse brain development, with newly isolated complementary DNA probes. J. Cell Biol. 1984, 98, 1090–1097.

- Sultan, A.; Nesslany, F.; Violet, M.; Bégard, S.; Loyens, A.; Talahari, S.; Mansuroglu, Z.; Marzin, D.; Sergeant, N.; Humez, S.; et al. Nuclear tau, a key player in neuronal DNA protection. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 4566–4575.

- Papasozomenos, S.C.; Binder, L.I. Phosphorylation determines two distinct species of Tau in the central nervous system. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 1987, 8, 210–226.

- Liu, C.; Götz, J. Profiling murine tau with 0N, 1N and 2N isoform-specific antibodies in brain and peripheral organs reveals distinct subcellular localization, with the 1N isoform being enriched in the nucleus. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84849.

- Chang, C.W.; Shao, E.; Mucke, L. Tau: Enabler of diverse brain disorders and target of rapidly evolving therapeutic strategies. Science 2021, 371, eabb8255.

- Andreadis, A. Tau gene alternative splicing: Expression patterns, regulation and modulation of function in normal brain and neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Basis Dis. 2005, 1739, 91–103.

- Drubin, D.G.; Kirschner, M.W. Tau protein function in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 1986, 103, 2739–2746.

- Panda, D.; Goode, B.L.; Feinstein, S.C.; Wilson, L. Kinetic stabilization of microtubule dynamics at steady state by tau and microtubule-binding domains of tau. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 11117–11127.

- Trinczek, B.; Biernat, J.; Baumann, K.; Mandelkow, E.M.; Mandelkow, E. Domains of tau protein, differential phosphorylation, and dynamic instability of microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell 1995, 6, 1887–1902.

- Dawson, H.N.; Ferreira, A.; Eyster, M.V.; Ghoshal, N.; Binder, L.I.; Vitek, M.P. Inhibition of neuronal maturation in primary hippocampal neurons from tau deficient mice. J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 1179–1187.

- Harada, A.; Oguchi, K.; Okabe, S.; Kuno, J.; Terada, S.; Ohshima, T.; Sato-Yoshitake, R.; Takei, Y.; Noda, T.; Hirokawa, N. Altered microtubule organization in small-calibre axons of mice lacking tau protein. Nature 1994, 369, 488–491.

- Tucker, K.L.; Meyer, M.; Barde, Y.A. Neurotrophins are required for nerve growth during development. Nat. Neurosci. 2001, 4, 29–37.

- Dixit, R.; Ross, J.L.; Goldman, Y.E.; Holzbaur, E.L. Differential regulation of dynein and kinesin motor proteins by tau. Science 2008, 319, 1086–1089.

- Konzack, S.; Thies, E.; Marx, A.; Mandelkow, E.M.; Mandelkow, E. Swimming against the tide: Mobility of the microtubule-associated protein tau in neurons. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 9916–9927.

- Utton, M.A.; Noble, W.J.; Hill, J.E.; Anderton, B.H.; Hanger, D.P. Molecular motors implicated in the axonal transport of tau and alpha-synuclein. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 4645–4654.

- Vershinin, M.; Carter, B.C.; Razafsky, D.S.; King, S.J.; Gross, S.P. Multiple-motor based transport and its regulation by Tau. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 87–92.

- Kanaan, N.M.; Morfini, G.A.; LaPointe, N.E.; Pigino, G.F.; Patterson, K.R.; Song, Y.; Andreadis, A.; Fu, Y.; Brady, S.T.; Binder, L.I. Pathogenic forms of tau inhibit kinesin-dependent axonal transport through a mechanism involving activation of axonal phosphotransferases. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 9858–9868.

- Vossel, K.A.; Xu, J.C.; Fomenko, V.; Miyamoto, T.; Suberbielle, E.; Knox, J.A.; Ho, K.; Kim, D.H.; Yu, G.Q.; Mucke, L. Tau reduction prevents Aβ-induced axonal transport deficits by blocking activation of GSK3β. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 209, 419–433.

- Vossel, K.A.; Zhang, K.; Brodbeck, J.; Daub, A.C.; Sharma, P.; Finkbeiner, S.; Cui, B.; Mucke, L. Tau reduction prevents Abeta-induced defects in axonal transport. Science 2010, 330, 198.

- Yuan, A.; Kumar, A.; Peterhoff, C.; Duff, K.; Nixon, R.A. Axonal transport rates in vivo are unaffected by tau deletion or overexpression in mice. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 1682–1687.

- Takei, Y.; Teng, J.; Harada, A.; Hirokawa, N. Defects in axonal elongation and neuronal migration in mice with disrupted tau and map1b genes. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 150, 989–1000.

- Frandemiche, M.L.; De Seranno, S.; Rush, T.; Borel, E.; Elie, A.; Arnal, I.; Lanté, F.; Buisson, A. Activity-dependent tau protein translocation to excitatory synapse is disrupted by exposure to amyloid-beta oligomers. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 6084–6097.

- Kimura, T.; Whitcomb, D.J.; Jo, J.; Regan, P.; Piers, T.; Heo, S.; Brown, C.; Hashikawa, T.; Murayama, M.; Seok, H.; et al. Microtubule-associated protein tau is essential for long-term depression in the hippocampus. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond B. Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130144.

- Ahmed, T.; Van der Jeugd, A.; Blum, D.; Galas, M.C.; D’Hooge, R.; Buee, L.; Balschun, D. Cognition and hippocampal synaptic plasticity in mice with a homozygous tau deletion. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, 2474–2478.

- Violet, M.; Delattre, L.; Tardivel, M.; Sultan, A.; Chauderlier, A.; Caillierez, R.; Talahari, S.; Nesslany, F.; Lefebvre, B.; Bonnefoy, E.; et al. A major role for Tau in neuronal DNA and RNA protection in vivo under physiological and hyperthermic conditions. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014, 8, 84.

- Mueller, R.L.; Combs, B.; Alhadidy, M.M.; Brady, S.T.; Morfini, G.A.; Kanaan, N.M. Tau: A Signaling Hub Protein. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 647054.

- Bierer, L.M.; Hof, P.R.; Purohit, D.P.; Carlin, L.; Schmeidler, J.; Davis, K.L.; Perl, D.P. Neocortical neurofibrillary tangles correlate with dementia severity in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch. Neurol. 1995, 52, 81–88.

- Sarrazin, S.; Lamanna, W.C.; Esko, J.D. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3.

- Bernfield, M.; Gotte, M.; Park, P.W.; Reizes, O.; Fitzgerald, M.L.; Lincecum, J.; Zako, M. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999, 68, 729–777.

- Huynh, M.B.; Ouidja, M.O.; Chantepie, S.; Carpentier, G.; Maiza, A.; Zhang, G.; Vilares, J.; Raisman-Vozari, R.; Papy-Garcia, D. Glycosaminoglycans from Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus have altered capacities to bind and regulate growth factors activities and to bind tau. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209573.

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Song, X.; Xiao, Y.; Su, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; Eliezer, D.; et al. 3-O-Sulfation of Heparan Sulfate Enhances Tau Interaction and Cellular Uptake. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 1818–1827.

- Snow, A.D.; Cummings, J.A.; Lake, T. The Unifying Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans/Glycosaminoglycans Are Key as First Hypothesized Over 30 Years Ago. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 710683.

- Stopschinski, B.E.; Holmes, B.B.; Miller, G.M.; Manon, V.A.; Vaquer-Alicea, J.; Prueitt, W.L.; Hsieh-Wilson, L.C.; Diamond, M.I. Specific glycosaminoglycan chain length and sulfation patterns are required for cell uptake of tau versus alpha-synuclein and beta-amyloid aggregates. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 10826–10840.

- Ledin, J.; Staatz, W.; Li, J.P.; Gotte, M.; Selleck, S.; Kjellen, L.; Spillmann, D. Heparan sulfate structure in mice with genetically modified heparan sulfate production. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 42732–42741.

- Mah, D.; Zhao, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Linhardt, R.; Wang, C. The Sulfation Code of Tauopathies: Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans in the Prion Like Spread of Tau Pathology. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 671458.

- Alavi Naini, S.M.; Soussi-Yanicostas, N. Heparan Sulfate as a Therapeutic Target in Tauopathies: Insights From Zebrafish. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 163.

- Su, J.H.; Cummings, B.J.; Cotman, C.W. Localization of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan and proteoglycan core protein in aged brain and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 1992, 51, 801–813.

- Snow, A.D.; Mar, H.; Nochlin, D.; Sekiguchi, R.T.; Kimata, K.; Koike, Y.; Wight, T.N. Early accumulation of heparan sulfate in neurons and in the beta-amyloid protein-containing lesions of Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome. Am. J. Pathol. 1990, 137, 1253–1270.

- Farshi, P.; Ohlig, S.; Pickhinke, U.; Hoing, S.; Jochmann, K.; Lawrence, R.; Dreier, R.; Dierker, T.; Grobe, K. Dual roles of the Cardin-Weintraub motif in multimeric Sonic hedgehog. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 23608–23619.

- Torrent, M.; Nogues, M.V.; Andreu, D.; Boix, E. The “CPC clip motif”: A conserved structural signature for heparin-binding proteins. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42692.

- Kato, T.; Sasaki, H.; Katagiri, T.; Sasaki, H.; Koiwai, K.; Youki, H.; Totsuka, S.; Ishii, T. The binding of basic fibroblast growth factor to Alzheimer’s neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques. Neurosci. Lett. 1991, 122, 33–36.

- Perry, G.; Siedlak, S.L.; Richey, P.; Kawai, M.; Cras, P.; Kalaria, R.N.; Galloway, P.G.; Scardina, J.M.; Cordell, B.; Greenberg, B.D.; et al. Association of heparan sulfate proteoglycan with the neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 1991, 11, 3679–3683.

- Spillantini, M.G.; Tolnay, M.; Love, S.; Goedert, M. Microtubule-associated protein tau, heparan sulphate and alpha-synuclein in several neurodegenerative diseases with dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 1999, 97, 585–594.

- Zhao, J.; Huvent, I.; Lippens, G.; Eliezer, D.; Zhang, A.; Li, Q.; Tessier, P.; Linhardt, R.J.; Zhang, F.; Wang, C. Glycan Determinants of Heparin-Tau Interaction. Biophys. J. 2017, 112, 921–932.

- Mukrasch, M.D.; Biernat, J.; von Bergen, M.; Griesinger, C.; Mandelkow, E.; Zweckstetter, M. Sites of tau important for aggregation populate -structure and bind to microtubules and polyanions. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 24978–24986.

- Murray, A.Y.L.; Gibson, J.M.; Liu, J.; Eliezer, D.; Lippens, G.; Zhang, F.; Linhardt, R.J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, C. Proline-Rich Region II (PRR2) Plays an Important Role in Tau-Glycan Interaction: An NMR Study. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1573.

- Holmes, B.B.; DeVos, S.L.; Kfoury, N.; Li, M.; Jacks, R.; Yanamandra, K.; Ouidja, M.O.; Brodsky, F.M.; Marasa, J.; Bagchi, D.P.; et al. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate internalization and propagation of specific proteopathic seeds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E3138–E3147.

- Pérez, M.; Avila, J.; Hernández, F. Propagation of Tau via Extracellular Vesicles. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 698.

- Toledo, J.B.; Zetterberg, H.; van Harten, A.C.; Glodzik, L.; Martinez-Lage, P.; Bocchio-Chiavetto, L.; Rami, L.; Hansson, O.; Sperling, R.; Engelborghs, S.; et al. Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarker in cognitively normal subjects. Brain 2015, 138, 2701–2715.

- Sutphen, C.L.; Jasielec, M.S.; Shah, A.R.; Macy, E.M.; Xiong, C.; Vlassenko, A.G.; Benzinger, T.L.; Stoops, E.E.; Vanderstichele, H.M.; Brix, B.; et al. Longitudinal Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarker Changes in Preclinical Alzheimer Disease During Middle Age. JAMA Neurol. 2015, 72, 1029–1042.

- Pilliod, J.; Desjardins, A.; Pernegre, C.; Jamann, H.; Larochelle, C.; Fon, E.A.; Leclerc, N. Clearance of intracellular tau protein from neuronal cells via VAMP8-induced secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 17827–17841.

- Merezhko, M.; Uronen, R.L.; Huttunen, H.J. The Cell Biology of Tau Secretion. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 569818.

- Xu, Y.; Cui, L.; Dibello, A.; Wang, L.; Lee, J.; Saidi, L.; Lee, J.G.; Ye, Y. DNAJC5 facilitates USP19-dependent unconventional secretion of misfolded cytosolic proteins. Cell Discov. 2018, 4, 11.

- Merezhko, M.; Brunello, C.A.; Yan, X.; Vihinen, H.; Jokitalo, E.; Uronen, R.L.; Huttunen, H.J. Secretion of Tau via an Unconventional Non-vesicular Mechanism. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 2027–2035.e2024.

- Katsinelos, T.; Zeitler, M.; Dimou, E.; Karakatsani, A.; Muller, H.M.; Nachman, E.; Steringer, J.P.; Ruiz de Almodovar, C.; Nickel, W.; Jahn, T.R. Unconventional Secretion Mediates the Trans-cellular Spreading of Tau. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 2039–2055.

- Mirbaha, H.; Holmes, B.B.; Sanders, D.W.; Bieschke, J.; Diamond, M.I. Tau Trimers Are the Minimal Propagation Unit Spontaneously Internalized to Seed Intracellular Aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 14893–14903.

- Sepulveda-Diaz, J.E.; Alavi Naini, S.M.; Huynh, M.B.; Ouidja, M.O.; Yanicostas, C.; Chantepie, S.; Villares, J.; Lamari, F.; Jospin, E.; van Kuppevelt, T.H.; et al. HS3ST2 expression is critical for the abnormal phosphorylation of tau in Alzheimer’s disease-related tau pathology. Brain 2015, 138, 1339–1354.

- Rauch, J.N.; Chen, J.J.; Sorum, A.W.; Miller, G.M.; Sharf, T.; See, S.K.; Hsieh-Wilson, L.C.; Kampmann, M.; Kosik, K.S. Tau Internalization is Regulated by 6-O Sulfation on Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans (HSPGs). Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6382.

- Qiu, H.; Shi, S.; Yue, J.; Xin, M.; Nairn, A.V.; Lin, L.; Liu, X.; Li, G.; Archer-Hartmann, S.A.; Dela Rosa, M.; et al. A mutant-cell library for systematic analysis of heparan sulfate structure-function relationships. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 889–899.

- Perea, J.R.; Lopez, E.; Diez-Ballesteros, J.C.; Avila, J.; Hernandez, F.; Bolos, M. Extracellular Monomeric Tau Is Internalized by Astrocytes. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 442.

- Arrasate, M.; Pérez, M.; Valpuesta, J.M.; Avila, J. Role of glycosaminoglycans in determining the helicity of paired helical filaments. Am. J. Pathol. 1997, 151, 1115–1122.

- Perez, M.; Valpuesta, J.M.; Medina, M.; Montejo de Garcini, E.; Avila, J. Polymerization of tau into filaments in the presence of heparin: The minimal sequence required for tau-tau interaction. J. Neurochem. 1996, 67, 1183–1190.

- Fichou, Y.; Lin, Y.; Rauch, J.N.; Vigers, M.; Zeng, Z.; Srivastava, M.; Keller, T.J.; Freed, J.H.; Kosik, K.S.; Han, S. Cofactors are essential constituents of stable and seeding-active tau fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 13234–13239.

- Townsend, D.; Fullwood, N.J.; Yates, E.A.; Middleton, D.A. Aggregation Kinetics and Filament Structure of a Tau Fragment Are Influenced by the Sulfation Pattern of the Cofactor Heparin. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 4003–4014.

- Paudel, H.K.; Li, W. Heparin-induced conformational change in microtubule-associated protein Tau as detected by chemical cross-linking and phosphopeptide mapping. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 8029–8038.

- Martin, L.; Latypova, X.; Wilson, C.M.; Magnaudeix, A.; Perrin, M.-L.; Yardin, C.; Terro, F. Tau protein kinases: Involvement in Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2013, 12, 289–309.

- Maïza, A.; Chantepie, S.; Vera, C.; Fifre, A.; Huynh, M.B.; Stettler, O.; Ouidja, M.O.; Papy-Garcia, D. The role of heparan sulfates in protein aggregation and their potential impact on neurodegeneration. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 3806–3818.

- Huynh, M.B.; Rebergue, N.; Merrick, H.; Gomez-Henao, W.; Jospin, E.; Biard, D.S.F.; Papy-Garcia, D. HS3ST2 expression induces the cell autonomous aggregation of tau. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10850.

- Hudak, A.; Kusz, E.; Domonkos, I.; Josvay, K.; Kodamullil, A.T.; Szilak, L.; Hofmann-Apitius, M.; Letoha, T. Contribution of syndecans to cellular uptake and fibrillation of alpha-synuclein and tau. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16543.

- Donahue, J.E.; Berzin, T.M.; Rafii, M.S.; Glass, D.J.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Fallon, J.R.; Stopa, E.G. Agrin in Alzheimer’s disease: Altered solubility and abnormal distribution within microvasculature and brain parenchyma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 6468–6472.

- Kolset, S.O.; Pejler, G. Serglycin: A structural and functional chameleon with wide impact on immune cells. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 4927–4933.

- Lorente-Gea, L.; Garcia, B.; Martin, C.; Ordiales, H.; Garcia-Suarez, O.; Pina-Batista, K.M.; Merayo-Lloves, J.; Quiros, L.M.; Fernandez-Vega, I. Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans Undergo Differential Expression Alterations in Alzheimer Disease Brains. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 79, 474–483.

- Shimizu, H.; Ghazizadeh, M.; Sato, S.; Oguro, T.; Kawanami, O. Interaction between β-amyloid protein and heparan sulfate proteoglycans from the cerebral capillary basement membrane in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 16, 277–282.

- Wang, Z.; Arnold, K.; Dhurandahare, V.M.; Xu, Y.; Pagadala, V.; Labra, E.; Jeske, W.; Fareed, J.; Gearing, M.; Liu, J. Analysis of 3-O-Sulfated Heparan Sulfate Using Isotopically L.Labeled Oligosaccharide Calibrants. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 2950–2957.

- Roberts, R.O.; Kang, Y.N.; Hu, C.; Moser, C.D.; Wang, S.; Moore, M.J.; Graham, R.P.; Lai, J.-P.; Petersen, R.C.; Roberts, L.R. Decreased Expression of Sulfatase 2 in the Brains of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: Implications for Regulation of Neuronal Cell Signaling. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2017, 1, 115–124.

- Pérez-López, N.; Martín, C.; García, B.; Solís-Hernández, M.P.; Rodríguez, D.; Alcalde, I.; Merayo, J.; Fernández-Vega, I.; Quirós, L.M. Alterations in the Expression of the Genes Responsible for the Synthesis of Heparan Sulfate in Brains With Alzheimer Disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2021, 80, 446–456.