| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andre Skirtach | + 4280 word(s) | 4280 | 2020-11-26 04:25:17 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | Meta information modification | 4280 | 2020-12-17 04:49:02 | | |

Video Upload Options

Originally regarded as auxiliary additives, nanoparticles have become important constituents of polyelectrolyte multilayers. They represent the key components to enhance mechanical properties, enable activation by laser light or ultrasound, construct anisotropic and multicompartment structures, and facilitate the development of novel sensors and movable particles.

1. Introduction

Versatile LbL (layer-by-layer) polyelectrolyte multilayer coatings have steadily drawn the increasing attention of researchers. This is driven by various factors including the versatility of the approach and an extensive range of applications, which is steadily continuing to increase. Originally, LbL was developed as planar layers [1]. In such an assembly [2], the structure of polyelectrolytes, the influence of water, pH, and salts on the LbL assembly have been investigated Various interactions and assembly methods [3][4] in the LbL assembly have been explored, including the electrostatic interaction, hydrogen bonding [5], while micrometre thick films have been also developed [6]. The extensive range of application of planar LbL coatings has included antifog [7]and ultraviolet (UV)-protective coatings [7], cell adhesion and tissue engineering [8]. A fundamental understanding of the interaction of polyelectrolytes has opened opportunities for versatile assembly of polymers incorporating diverse building blocks. Nanoparticles (NPs) have been explored as components of the LbL assembly in earlier publications [9][10][11] but their full potential has been recognised somewhat later, after enabling remote opening, increasing the efficiency of the effect of ultrasound on affecting the polyelectrolyte coatings, enhancing mechanical properties of capsules, extending the range of materials for sensors.

Originally developed for planar structures and substrates, the LbL approach has been transferred to spherical templates, which led to preparation of an LbL assembly freely suspended in water. This can be done by applying the LbL coatings onto colloidal particles, and subsequently dissolving the colloidal particle, which is also called a template for LbL assembly. The spherical shells, also called capsules, enable the polyelectrolytes to be freely suspended in an aqueous solution: the substrate holding the planar polyelectrolyte multilayers is thus not present. In this case, the zeta-potential of capsules can be easily measured, and polyelectrolytes are bound to each other directly, without a substrate. As a result, various stimuli can now be applied to control the LbL assembly [12], as it was shown, for example, studying the influence of pH and salt on the interaction of polyelectrolytes [13][14].

2. Functionalization of Polyelectrolyte Multilayers—Organic versus Inorganic Building Blocks

2.1. Incorporation of Dyes in Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Coatings—Bringing Multifunctionality through Organic Moieties

Various materials [15][16][17][18][19][20][21] can be incorporated into self-assembled LbL coatings. Although charged molecules have been traditionally employed in the LbL assembly, non-charged molecules or dyes can be ordered in LbL films by means of chemical bonding or by carriers. Pyrene molecules were shown to be incorporated in polyelectrolyte layers in a liposome-mediated process. In this regard, pyrene molecules were encapsulated into poly(acrylic acid)-stabilized cetyltrimethylammonium bromide micelles followed by LbL assembly of the micelles in a poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (PDADMAC) framework [22], where optical signal is detected by detecting optical resonances of light propagating around a sphere, also referred to as whispery gallery modes. Moreover, the inclusion of dye into nanocomposite LbL-assembled film was found to be a simple method to provide spectroscopic analysis of stability (both structural and chemical) and adsorption properties of the film [23]. Additionally, fluorescent dyes bound to non-fluorescent particles via LbL films were shown to generate a strong whispering gallery modes signal for bioanalysis [24]. Incorporated in LbL layers electroactive dyes have also received substantial attention. It was shown that the way to incorporate electroactive anthraquinone dye to LbL films strongly influences its electrochemical properties and chemical properties [25]. Metachromic cationic dye methylene blue was investigated for organization in the LbL framework [26]. In addition, photocleavable chromophores [27], laser absorbing dye (IR-806) [28], bacteriorhodopsin [29], phthalocyanine [30], porphyrin [31][32], and naphthalocyanine [33] have been also incorporated in microcapsules for remote opening by laser light, but it was also noticed that inorganic nanoparticles appeared to be much more effective laser light absorbers

2.2. Incorporation of Nanoparticles in LbL Coatings—Hardness Enhancement and Additional Properties through Inorganic Building Blocks

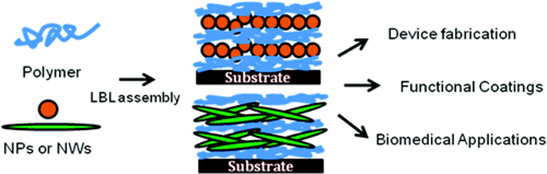

Although nanoparticles have been perhaps most frequently used for LbL functionalization, various nanostructured building blocks, nanocomposite films with nanoparticles embedded in the layered structure have been shown to be a highly effective class of material to tune various properties (among which mechanical stiffness) with a high accuracy [34], Figure 1. Various methods have been used for LbL assembly with nanoparticles, where in addition to a dipping or incubation, spin-spray LbL assembly [35], spin-coating [36], spray assisted alignments [37], and cross-linking after infiltration [38] were used. Nanocomposite LbL films containing immobilized ZnO/SiO2 nanoparticles were investigated to provide UV protection properties [39]. Alternating layers of cerium oxide nanoparticles (CONP)/alginate were fabricated on top of beta cells via LbL exhibiting robust antioxidant activity and providing excellent protection to these cells upon exposure to 10−4 M of H2O2 without affecting the metabolism of the cells [40].

Figure 1. Schematics of incorporation of inorganic nanoparticles, nanowires and nanosheets in layer-by-layer (LbL) assembly. Reproduced with permission from [34]. Copyright 2008 American Chemical Society.

3. Planar LbL Coatings and Their Functionalization by Nanoparticles

Nanoparticles have been essential components of planar layers, where they were used for enhancement of mechanical properties, remote activation, controlling the stiffness of the coatings, for quantum dots incorporation and corrosion protection.

3.1. Enhancement of Mechanical Properties and Remote Acteivation of LbL Coatings

Mechanical stability of capsules and films plays an essential role in enabling practical applications. The addition of nanoparticles would thus increase the shell stiffness. It should be added that the same concept of strengthening mechanical properties of LbL by adding nanoparticles has been also shown for planar coatings. In regard with mechanical properties of planar coatings, mechanical properties of nanometre-thin [41] LbL films [42] (each LbL layer was reported to be 1–2 nm) resemble those of the substrate on which they are assembled (often glass, metal or plastic). But thicker LbL films [43], with a high molecular dynamic of polyelectrolytes [44], are rather soft, hindering cell growth in biomedical applications. One way to increase the stiffness of the coatings is to use chemical cross-linking [45][46]. Another possibility to improve the mechanical properties and enable the adherence of cells on the coatings is to functionalize the surface with metal nanoparticles [47]. Recently, particles and nanoparticles have been used to stimulate cell adhesion on the planar and soft hydrogel coatings relevant for osteoblasts and different types of cells [48].

3.2. Passive and Active Activation of LbL Coatings

Passively active coatings are those in which they or some of their components exhibit a certain functionality. For example, alternating layers of hyaluronic acid–dopamine conjugate with silver nanoparticles demonstrated a remarkable antibacterial [49][50] effect as well as improved adhesion, proliferation, and viability of cells to the surface, which promoted the formation of an apatite layer resembling bones [51]. In another example, incorporating of inorganic particles [52] into hybrid (organic-inorganic) coatings enabled effective cell growth, which is seen of a particular importance to various areas of tissue engineering [53].

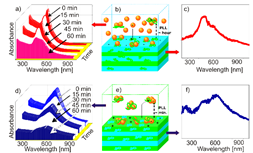

An active functionality of nanoparticles was to functionalize the micrometre thick LbL coatings with nanoparticles and use them as active absorption centres for remote laser action. Nanoparticle functionalization of such a soft LbL coating is depicted in Figure 2 (left), where step-by-step assembly is presented for non-aggregated (red) and aggregated (blue) states of nanoparticles. Choosing proper aggregation state of nanoparticles and laser wavelength corresponding to the maximum absorption of NPs, one can locally cross-link the surface of films exposed to laser, Figure 2 (right). Even more drastic action of laser-nanoparticle interaction has been implemented in cell detachment [54], differentiation [55], and cell death induction [56].

Figure 2. (Left) Kinetics of adsorption of non-aggregated (a–c) and aggregated (d–f) nanoparticles onto biocompatible poly-L-lysine (PLL)/hyaluronic acid (HA) films. (Adsorption on (PLL/HA)24 films are shown in (a–c), while adsorption on (PLL/HA)24PLL films is demonstrated in (d–f)). Ultraviolet–visible (UV/Vis) absorption spectra of the supernatant solution during adsorption in (a) and (d) were recorded at 15 min time intervals. Schematics of the interaction of nanoparticles and the films in non-aggregated and aggregated states are demonstrated in (b) and (e), and the corresponding UV/Vis absorption spectra of the films after nanoparticle adsorption are given in (c) and (f), respectively. (Right) Confocal laser scanning microscope images of a (PLL/HA)24 film functionalized with aggregated gold nanoparticles (a). The zoomed-in area shown in (b) was exposed to a near-infrared (NIR) laser leaving characteristic dark spots, (c). The dark spots (c) affected by the near-IR laser can be also seen in the transmission image, (d). The scale bars in (a–d) correspond to 15 µm. The technique described in (a–d) is used to write MPI-KG (Max-Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces (German spelling)) (e), the scale bar here corresponds to 20 µm. Reproduced with permission from [57]. Copyright 2010 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH.

However, this is not the only functionality of the nanoparticles in the coatings—they can be also used to control the masking for fabricating Janus particles.

3.3. Assembling Janus Particles and Capsules Using LbL Coatings

Janus particles have at least two different surfaces referred to one structural unit [58]. Interest in Janus capsules is associated with a combination of delivery [59] for various therapies and self-propelled micro-/nanomotor approaches [60][61][62]. Applied to the encapsulation process, Janus particles combine different properties and provide a range of functions such as delivery, recognition, release of therapeutics, enzymatic activity, physical and chemical sensing [63][64]. In particular, drug delivery is focused on: (i) encapsulation of active chemicals [65], (ii) targeted delivery [66], and (iii) stimuli-responsive release. Therefore, approaches for Janus structure creation aim for a high loading capacity [67] via hierarchical organization.

Methods for fabrication of the Janus particles can be grouped into three main approaches: direct synthesis, chemical modification of particles at biphasic interfaces, and topographically selective modification of particles [68][69][70]. Typically, the following methods are used for fabrication: sputtering [71], gel trapping [72], microcontact printing[73], and masking [74]. Another example of such an application is where nanoparticles were used to control the stiffness of the coatings, which, in turn, were used as a substrate-template for assembly of Janus particles and capsules [75]. The embedding has been regulated by the stiffness of the coatings, which is proportional to the concentration of nanoparticles incorporated into the surface of the coatings.

An interesting uncomplicated way of polyampholyte Janus-like particles formation was shown recently [76]. There, sites of molecules with opposite charge were pooled apart. The polyampholyte structure suggests that such Janus-like particles are dependent on both pH of the solution and its temperature. To create biocompatible Janus polyelectrolyte particles with a high monodispersity, the layer-by-layer technique was combined with multiphasic fabrication and patterned wettability [77]. Engineering self-propelled motors having a controllable speed can be of interest for many applications. For example, it was suggested to use bubble propulsion to move Janus polyelectrolyte particles [78]. Janus microcapsules were formed by grafting polyelectrolyte salt-responsive brushes onto preformed (poly(styrene sulfonate) PSS/(polyallylamine hydrochloride) PAH)4 microcapsule protected from one side. Depending on the presence of chlorate and polyphosphate anions brush modulation between hydrophobic and hydrophilic configurations was achieved. Upon gradually changed ion concentration, brushes could partially change their state, thereby adjusting the speed of the particle. In other words, it was possible to create particles with continuously propagating with adjustable speeds completely autonomously due to the surrounding chemical concentration gradients in the solution.

Recently, near-infrared (IR) irradiation was used to induce propulsion of Janus motors [79]. There, the particles constructed with erythrocyte membrane-cloak were used to ablate thrombus. Positively charged chitosan and negatively charged heparin were assembled using the LbL approach for building biocompatible and biodegradable capsules. The sensitivity to near infrared irradiation of capsules was achieved by using a sputtered gold layer on a part of the capsule. We note also that other polyelectrolyte systems modified with Au, e.g., hyaluronic acid (HA)/poly-L-lysine (PLL) (HA/PLL)12 , became sensitive to near-infrared irradiation. Due to asymmetric coverage of particles with gold IR irradiation crates a local thermal gradient. That led to self-propulsion of the particles, based on thermophoresis effect. Consequently, the intensity of the irradiation directly influences the motile of the particles up to on-off switching behaviour. Besides Au, other nanoparticles, e.g., Pt, and enzymes, were assembled to self-propel capsules [80][81]. In addition, bending and rotational motions of micromotors were also implemented [82] in polymer tubes with poly(allylamine hydrochloride) as positively charged and poly(acrylic acid) as negatively charged polyelectrolytes. Alkaline treatment of one longitudinal side of the tube leads to asymmetry in action (swellability), thereby providing a bent motion. When placed in a fuel solution, such supramolecular structure demonstrates bending for soft connector tubes, and stable rotation for rigid angled ones. In addition, the connection angle determines the rotation velocity. It was noted that such structures could find their application in micro- and nano-machine engineering and biomedicine, such as microscale surgery and drug delivery.

Systematic description and comparison of the influence of grafting density onto interface properties [83] showed that swelling on planar and curved substrates upon changing of grafting density behave in different ways. In other applications, moving Janus capsules was suggested for separation of organics [84], where a reversible adsorption of organic dye by multilayered polyelectrolyte structure was shown. Thus, it is claimed to adsorb about 90% of dye species at pH higher than 9.0 and to release them back at the neutral pH value. The adsorption process is presumably ruled by electrostatic interaction of positive sites of polymer structure and the anionic form of dyes. Application of the above structures in water analysis has been proposed. Contrary to the approach used in classical drug delivery [85], a method of HeLa controlled transportation of cells was also presented. The system is based on relatively known and popular bubble-propelled particles, constructed of polyelectrolytes. It is reported that cells survive both the Janus particle attachment and subsequent movement in 5% H2O2 solution for over 20 min. A magnetic field is also claimed to be guideline technique by tuning the friction of moving object. Thereby, up to 90% of moderation could be achieved. Similarly, a high suitability of anisotropic shell for cell or cellular compartments has been also highlighted [86].

Janus capsules coated with leucocyte membranes were proposed as the possible treatment of some cancer cases [87]. The photothermal effect combined with a rapid water evaporation was used to deliver and attach capsules to the cancer cell wall and subsequently induce a damage to cells. Another publication [88] also highlights the possibility of coating Janus particles with leucocyte membrane to adhere to cancer cells. The second step of phagocytose is also observed for such cells labeled by Janus particles. Janus particles constructed to exhibit thermophoresis were applied for welding of mouse tissue via infrared laser heating [89] with the photothermal heating confined on single particles. Eventually, mechanical restoration of welded mouse tissue was proved with a set of mechanical characterization techniques.

Nanoparticle functionalization of planar LbL coatings has been shown to play an important role in controlling the patches of Janus particles and capsules, but nanoparticles have been also directly applied to release adsorbed materials on the surface coatings [90].

3.4. Corrosion Protection of the Coatings

Application of polyelectrolyte layer-by-layer deposition spurred interest in the field of corrosion protection as a possible way to replace toxic Cr(VI)-compounds. One of the main advantages of polyelectrolyte structures is their light, pH, and humidity responsiveness, which would enable a self-healing process by changes of environment that existed at the beginning of the corrosion. Such a system seems to be useful both for steel alloys [91] and non-ferrous materials [92][93][94].

The protective layer can consist of pure polyelectrolytes [92] (optionally with corrosion protective additives) and could be multi-layered with sol-gel and/or corrosion inhibitor coatings [91]. The more sophisticated way is based on creation micro- and nanocapsules with PE coatings. Capsules can be templated (the template is the dissolvable core) on SiO2 particles [93][95], TiO2 nanoparticles [95], nanotubes, and pure polyelectrolyte nanocapsules [96][97]. Different corrosive protection substances, such as benzotriazole [93][94][95] and its derivatives [97], and monomers for filling scratches for further induced polymerization, could be loaded inside these capsules. They are then incorporated in a more complex matrix such as sol-gel [98], epoxy [97] coatings, or polyelectrolyte multilayers [96]. Combined, these structures demonstrate mechanical strength, corrosion protection, and self-healing processes [99], triggered by initiation of corrosion or laser irradiation.

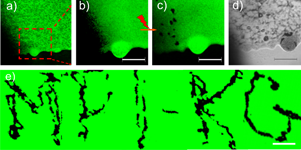

We highlight here the development of light-sensitive capsule-based active materials [100][101][102]. The principle of the approach is shown in Figure 3. Corrosion mitigating inhibitors encapsulated in the capsule with mesoporous core and light-controlled permeability of the shell have been used for developing coatings with self-healing functions, which are enabled by controllably releasing the inhibitor upon exposure to laser (infra-red) irradiation. Titania nanoparticles [100] can provide multilayers with photosensitivity. Thus, titania was used both as containers for loading benzotriazole (BTA) for corrosion inhibition and as photosensitive agents. Such capsules were then covered with polyelectrolytes, and they released inhibitor upon UV light irradiation.

Figure 3. (a) Scheme of light-responsive protective coating. Luminescent confocal images of polyelectrolyte containers with titania cores incorporated into SiOx-ZrOx films. The images are obtained (b) before and (c) after UV irradiation. The particles in the figures correspond to aggregates of nanocontainers. Three-dimensional (3D) maps of the ionic currents above the surface area correspond to a mechanical defect in sol-gel coating loaded with TiO2(benzotriazole)/(PEI/PSS)2 containers: (d) at the beginning moment on the artificial defect; (e) after 64 h of corrosion; (f) is (e) after UV-irradiation and inhibitor release. Solution: 0.1 M NaCl. Reproduced with permission from [100]. Copyright 2009 The Royal Society of Chemistry.

The conformational structure of polyelectrolytes depends on the pH of the environment. Thus, change in pH for certain configurations will result in different permeability of the structure. Thereby, the system could demonstrate both self-healing and self-regulation behaviour when pH changes due to corrosion process starts self-healing process. The reversible changes of polyelectrolyte permeability could be explained by locally changed pH of the solution, as the consequence of photocatalytic degradation of water on the titania. The end of irradiation or corrosion cause thus system relaxation, and particle returns to their initial structure. Visualization of local pH gradient is possible by model physico-chemical properties—scanning ion-selective electrode technique (SIET) [103][104][105].

The inclusion of metal nanoparticles via LbL procedure enabled the synthesis of materials for unusual applications too. Electroactive (2 nm in diameter) polyelectrolyte-capped Pt nanoparticles assembled into LbL arrays have been used in catalytic production of H2 [106]. Photocatalytic reduction [107] of noble metal particles on titania core leads to dual-wavelength responsiveness: in the UV to near-IR regions of electromagnetic spectrum. It is possible to regulate photocatalytically (auto-catalytic) waves of enzymatic reactions [108], switch biofilm fluorescence [109], build a platform for a chemical logic device [110], and perform sustainable diagnostics [111][112][113]. The trend in the field of encapsulated systems is to combine different functions in one capsule matrix. One such functionality is to control the release of biocides together with corrosion inhibitors [114], while a prospective approach can lead to building self-regulating biocide systems [115].

3.5. Development of Sensors and Biosensors Based on Layer-by-Layer Assembled Coatings

Gold nanoparticles (AuNP) embedded into the polyelectrolyte matrices on the top of optical fibre exhibited a high accuracy pH sensing functionality based on the localized surface plasmon resonance (SPR) [116]. Measurement of pH shifts [117] was also implemented by incorporating gold nanorods, by detecting the surface plasmon shift of dispersed nanorods upon pH rise [118]. In another application, starch-stabilized silver nanoparticles in 3-n-propylpyridinium silsesquioxane chloride matrices were shown to function as SPR-based electrochemical sensors [119].

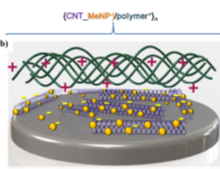

Hybrid materials assembled using carbon nanotubes and polyelectrolytes were shown to operate as effective membranes for the separation and rejection of ions [120]. Furthermore, the high electric conductivity of carbon nanotubes in a polymer framework allowed the development of multi-walled carbon nanotubes-based thin film electrodes transparent in the mid-IR (infrared) range [121].

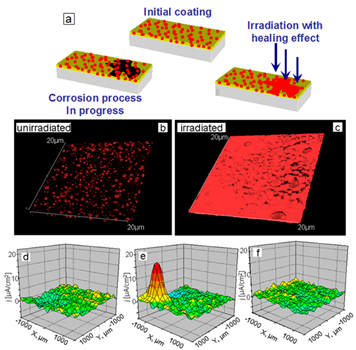

It can be mentioned that sensory functions in planar coatings [122], Figure 4, represent a complementary area to those broadly implemented by polyelectrolyte multilayer capsules [123][124][125].

|

|

|

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 4. Schematics of LbL assemblies of: (a) polymer/nanoparticle (NP)/enzyme, and (b) carbon nanotube/NP/polymer sensors. Reproduced with permission from [122]. Copyright 2015 Elsevier.

3.6. Other Nanostructured Inorganic Building Blocks in LbL Planar Coatings

Recently, a variety of materials were applied to design advanced LbL coatings. Quercetin-loaded tripolyphosphate nanoparticles were ordered in a film (by an alternative with hyaluronic acid) resulting in a multilayer film capable to improve anticoagulation performance of surfaces [126]. Polysaccharides and nanogels were employed in polyelectrolyte multilayers proving that the presence of nanogel particles is beneficial for construction of a drug depot system [127]. Linear photochromic norbornene polymers assembled in LbL films exhibited a drastic decrease of the merocyanine band under a prolonged white light irradiation that potentially could be employed as photo-controlled drug depot system [128]. Bioactive thin films were prepared via encapsulation of biomacromolecules such as an enzyme (beta-lactamase, BlaP) into aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes and their subsequent use for the fabrication of enzymatic coatings by LbL that potentially could act for effluent decontamination [129].

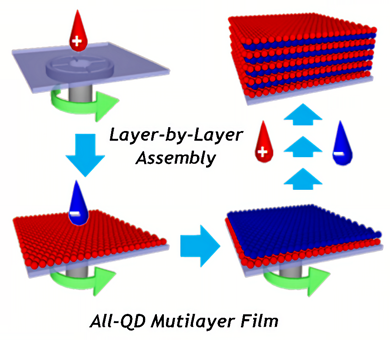

Application of quantum dots (QD) in capsules makes it possible to bring multifunctionality of encapsulation processes and sensor capabilities. Easily adjustable luminescence of QD has a high potential for applying QD-containing polyelectrolyte-based coatings and capsules for biological, particularly medical, and materials science as devices and theragnostic agents [130]. There are two trends in design of composite materials based on quantum dots and layer-by-layer technique. In the first approach, QD are incorporated into layer-by-layer films, Figure 5. For application of LbL technique, QDs are usually chemically modified with thioglycolic acid (TGA) [131], mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) [132], or mercaptoacetic acid (MAA) [133], and they have a negative zeta potential when cysteamine is applied [132].

Figure 5. Schematic for the preparation of all-quantum dot (QD) multilayer films based on spin-assisted layer-by-layer assembly by sequentially depositing oppositely charged QDs (blue QDs and red QDs represent negatively charged QDs (QD-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA)) and positively charged QDs (QD-cysteamine (CAm)), respectively). Reproduced with permission from [132]. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

The first approach has been conducted by reducing the toxicity of QDs, stabilization of dispersity, and optimization of distribution, while the QD optical properties were unaffected [134]. CdSe is the typical material for quantum dots, which are used for layer-by-layer coating functionalization. For example, MAA-treated QDs were coated by alternatively applying polyallylamine and polyvinyl sulfonic acid [133].

Materials prepared by the second approach find applications in designing flexible, organo-electronic devices [135]. Stabilization of QDs with polyelectrolytes provides the possibility of the energy transfer between bilayers of the charged polymers. The resulting film is reported to be sensitive for the detection of paraoxon [136] or deltamethrin. Incorporation of QD with graphene NPs in an alternative stacking manner in the PAH layers [137] leads to augmentation of the separation of charges and transport in GNs–CdS QDs composite film. A drawback of such methods is that CdSe nanoparticles undergo photooxidation in the polyelectrolyte matrix.

The LbL-assembled polyelectrolyte capsules can be functionalized with QD as biocompatible fluorescent agents for live-cell targeting [138][139][140]. In this case, polyelectrolyte film decreases the typical cytotoxic effect of the QD with the fluorescence properties remained. For example, compared to empty PLL/polyglutamic acid (PGA) capsules that do not influence the cell viability, CdTe- labelling of the same capsules displayed a higher cytotoxicity, but lower compared to pure CdTe QD [140]. A prospective field of engineering structures with semiconductor nanocrystals involves construction of complex ordered building blocks similar to those used in photonic crystals. Thus, demonstrated luminescence in both the IR and visible ranges from CdTe and HgTe [141] could be a starting point for development of sophisticated optoelectronics and optical telecommunications devices.

Biologically active QD-based hybrid nanocrystal/polyelectrolyte structures with an outer layer of anti-immunoglobulin G (anti-IgG) were shown to render some bio-specific properties to particles [142]. Considering the interesting info-chemistry [143][144], the optical coding and multiplexing can be achieved at different wavelengths and intensities by bringing in QDs in polyelectrolyte multilayers. To achieve that effect, it is possible to create bits of information by tuning the amount of red, green, and blue QD for achieving some characteristic colour ration. Combining these structures with some receptors makes it possible to identify various bio-processes [145], while gradient coatings [146] can stimulate combinatorial studies [147].

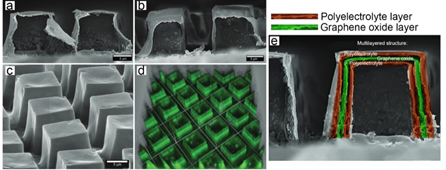

LbL were also functionalized by carbon-based fillers [148]]. Polyelectrolyte-assisted layer-by-layer fabrication of carbon-containing coatings was proposed to order carbon fillers providing superior properties of the films. The unique combination of carbon materials properties together with versatility of the LbL assembly allows fabrication of multifunctional nanocomposite materials with improved mechanical, optical, thermal, electromagnetic, electrochemical properties [149]. The unique properties of graphene enabled high-performance capacitors and effective electromagnetic shielding [150]. A wide range of coatings functionalized by carbon fillers is aimed at the development of materials with a gas barrier function [151]. The change in permeability of microcapsules tuned by graphene oxide was also applied in drug delivery to reduce the permeability of low molecular substances [152]. Furthermore, coatings can be obtained on surfaces with complex shapes to provide additional functionality, for example, coatings containing arrays of closed cavities can be obtained (so-called microchambers) to store and release functional cargo in a controlled manner. Functionalisation of microchambers by graphene oxide enabled release on demand by near-infrared (NIR) laser in the “therapeutic window” [153], Figure 6. An unusual application of graphene oxide was shown by the binary hybrid-filled LbL coatings, composed of graphene oxide and β-FeOOH nanorods, which enabled the reduction of flammability of polyurethane foams [154]. AuNP assembled in unconventional LbL architectures enabled analysis of hybridization reactions with the ssDNA monitored via methylene blue as the electrochemical indicator. Such an architecture was used as DNA electrochemical biosensors [155] along with Pd nanoparticle-based RNA biosensor [156].

Figure 6. SEM (scanning electron microscopy) images of LbL-assembled microchambers constructed from a pure polyelectrolyte film (a) and functionalised by graphene oxide (b,c) and its corresponding confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) image (d). Reproduced with permission from [153]. Copyright 2018 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH. (e) Schematics of the layered functionalization of microchambers by polyelectrolyte polymers and graphene.

In addition, carbon nanotubes and carbon-based fibres exhibit anisotropy upon ordering—a property useful in some applications, for example, in porous membranes [157]. It can be noted that many essential properties of LbL coatings, and particularly their permeability [158], depend on the concentration of polyelectrolytes, which was studied by the tangential streaming potential revealing that higher concentrations of polyelectrolytes are preferred for an effective adsorption [159]. In addition, some other nanostructured blocks, which extend functionalities of LbL coatings, include halloysites [160][161].

References

- Decher, G. Fuzzy Nanoassemblies: Toward Layered Polymeric Multicomposites. Science 1997, 277, 1232–1237.

- Lvov, Y.; Decher, G.; Möhwald, H. Assembly, structural characterization, and thermal behavior of layer-by-layer deposited ultrathin films of poly(vinyl sulfate) and poly(allylamine). Langmuir 1993, 9, 481–486.

- Nuraje, N.; Asmatulu, R.; Cohen, R.E.; Rubner, M.F. Durable Antifog Films from Layer-by-Layer Molecularly Blended Hydrophilic Polysaccharides. Langmuir 2011, 27, 782–791.

- Richardson, J.J.; Bjornmalm, M.; Caruso, F. Technology-driven layer-by-layer assembly of nanofilms. Science 2015, 348, aaa2491.

- Kozlovskaya, V.; Shamaev, A.; Sukhishvili, S.A. Tuning swelling pH and permeability of hydrogel multilayer capsules. Soft Matter 2008, 4, 1499–1507.

- Zhang, J.; Senger, B.; Vautier, D.; Picart, C.; Schaaf, P.; Voegel, J.-C.; Lavalle, P. Natural polyelectrolyte films based on layer-by layer deposition of collagen and hyaluronic acid. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3353–3361.

- Guin, T.; Cho, J.H.; Xiang, F.; Ellison, C.J.; Grunlan, J.C. Water-Based Melanin Multilayer Thin Films with Broadband UV Absorption. ACS Macro Lett. 2015, 4, 335–338.

- Gribova, V.; Auzely-Velty, R.; Picart, C. Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Assemblies on Materials Surfaces: From Cell Adhesion to Tissue Engineering. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 854–869.

- Kotov, N.A.; Dekany, I.; Fendler, J.H. Layer-by-Layer Self-Assembly of Polyelectrolyte-Semiconductor Nanoparticle Composite Films. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 13065–13069.

- Lee, D.; Rubner, M.F.; Cohen, R.E. All-Nanoparticle Thin-Film Coatings. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 2305–2312.

- Lvov, Y.; Ariga, K.; Onda, M.; Ichinose, I.; Kunitake, T. Alternate Assembly of Ordered Multilayers of SiO 2 and Other Nanoparticles and Polyions. Langmuir 1997, 13, 6195–6203.

- Delcea, M.; Möhwald, H.; Skirtach, A.G. Stimuli-responsive LbL capsules and nanoshells for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 63, 730–747.

- Déjugnat, C.; Haložan, D.; Sukhorukov, G.B. Defined Picogram Dose Inclusion and Release of Macromolecules using Polyelectrolyte Microcapsules. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2005, 26, 961–967.

- Mauser, T.; Déjugnat, C.; Sukhorukov, G.B. Balance of Hydrophobic and Electrostatic Forces in the pH Response of Weak Polyelectrolyte Capsules. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 20246–20253.

- Saveleva, M.S.; Eftekhari, K.; Abalymov, A.A.; Douglas, T.E.L.; Volodkin, D. V.; Parakhonskiy, B. V.; Skirtach, A.G. Hierarchy of Hybrid Materials—The Place of Inorganics-in-Organics in it, Their Composition and Applications. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 179.

- Kaniewska, K.; Karbarz, M.; Katz, E. Nanocomposite hydrogel films and coatings – Features and applications. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 20, 100776.

- Rial, R.; Liu, Z.; Ruso, J.M. Soft Actuated Hybrid Hydrogel with Bioinspired Complexity to Control Mechanical Flexure Behavior for Tissue Engineering. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1302.

- Park, M.-K.; Advincula, R.C. The Layer-by-Layer Assemblies of Polyelectrolytes and Nanomaterials as Films and Particle Coatings. In Functional Polymer Films; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2011; pp. 73–112.

- Ariga, K.; Hill, J.P.; Ji, Q. Organic-Inorganic Supramolecular Materials. In Supramolecular Soft Matter; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 43–55.

- Katagiri, K. Organic-inorganic nanohybrid particles for biomedical applications. In Bioceramics; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 113–135.

- Yan, X.; Zhu, P.; Li, J. Self-assembly and application of diphenylalanine-based nanostructures. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1877–1890.

- Liu, X.; Zhou, L.; Geng, W.; Sun, J. Layer-by-Layer-Assembled Multilayer Films of Polyelectrolyte-Stabilized Surfactant Micelles for the Incorporation of Noncharged Organic Dyes. Langmuir 2008, 24, 12986–12989.

- Szabó, T.; Péter, Z.; Illés, E.; Janovák, L.; Talyzin, A. Stability and dye inclusion of graphene oxide/polyelectrolyte layer-by-layer self-assembled films in saline, acidic and basic aqueous solutions. Carbon N. Y. 2017, 111, 350–357.

- Olszyna, M.; Debrassi, A.; Üzüm, C.; Dähne, L. Label-Free Bioanalysis Based on Low-Q Whispering Gallery Modes: Rapid Preparation of Microsensors by Means of Layer-by-Layer Technology. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1805998.

- Ma, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Kou, D.; Lutkenhaus, J. Layer-by-Layer Assembly and Electrochemical Study of Alizarin Red S-Based Thin Films. Polymers (Basel). 2019, 11, 165.

- Chakraborty, U.; Singha, T.; Chianelli, R.R.; Hansda, C.; Kumar Paul, P. Organic-inorganic hybrid layer-by-layer electrostatic self-assembled film of cationic dye Methylene Blue and a clay mineral: Spectroscopic and Atomic Force microscopic investigations. J. Lumin. 2017, 187, 322–332.

- Hu, X.; Qureishi, Z.; Thomas, S.W. Light-Controlled Selective Disruption, Multilevel Patterning, and Sequential Release with Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Films Incorporating Four Photocleavable Chromophores. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 2951–2960.

- Skirtach, A.G.A.G.; Antipov, A.A.; Shchukin, D.G.; Sukhorukov, G.B. Remote Activation of Capsules Containing Ag Nanoparticles and IR Dye by Laser Light. Langmuir 2004, 20, 6988–6992.

- Erokhina, S.; Benassi, L.; Bianchini, P.; Diaspro, A.; Erokhin, V.; Fontana, M.P. Light-Driven Release from Polymeric Microcapsules Functionalized with Bacteriorhodopsin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 9800–9804.

- Zeng, Y.; Wang, X.-L.; Yang, Y.-J.; Chen, J.-F.; Fu, J.; Tao, X. Assembling photosensitive capsules by phthalocyanines and polyelectrolytes for photodynamic therapy. Polymer (Guildf). 2011, 52, 1766–1771.

- Bédard, M.F.; Sadasivan, S.; Sukhorukov, G.B.; Skirtach, A. Assembling polyelectrolytes and porphyrins into hollow capsules with laser-responsive oxidative properties. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 2226–2233.

- Li, C.; Li, Z.-Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, K.; Gong, Y.-H.; Luo, G.-F.; Zhuo, R.-X.; Zhang, X.-Z. Porphyrin containing light-responsive capsules for controlled drug release. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 4623–4626.

- Marchenko, I. V.; Borodina, T.N.; Trushina, D.B.; Nabatov, B. V.; Logachev, V. V.; Plotnikov, G.S.; Baranov, A.N.; Saletskii, A.M.; Ryabova, A. V.; Bukreeva, T. V. Incorporation of Naphthalocyanine into Shells of Polyelectrolyte Capsules and Their Disruption under Laser Radiation. Colloid J. 2018, 80, 399–406.

- Srivastava, S.; Kotov, N.A. Composite Layer-by-Layer (LBL) assembly with inorganic nanoparticles and nanowires. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1831–1841.

- Gittleson, F.S.; Hwang, D.; Ryu, W.-H.; Hashmi, S.M.; Hwang, J.; Goh, T.; Taylor, A.D. Ultrathin Nanotube/Nanowire Electrodes by Spin–Spray Layer-by-Layer Assembly: A Concept for Transparent Energy Storage. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 10005–10017.

- Danglad-Flores, J.; Eftekhari, K.; Skirtach, A.G.; Riegler, H. Controlled Deposition of Nanosize and Microsize Particles by Spin-Casting. Langmuir 2019, 35, 3404–3412.

- Hu, H.; Pauly, M.; Felix, O.; Decher, G. Spray-assisted alignment of Layer-by-Layer assembled silver nanowires: a general approach for the preparation of highly anisotropic nano-composite films. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 1307–1314.

- Zhou, Y.; Cheng, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; An, Q.; Shi, F. A facile method for the construction of stable polymer–inorganic nanoparticle composite multilayers. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 11329–11334.

- Abd El-Hady, M.M.; Sharaf, S.; Farouk, A. Highly hydrophobic and UV protective properties of cotton fabric using layer by layer self-assembly technique. Cellulose 2020, 27, 1099–1110.

- Abuid, N.J.; Gattás-Asfura, K.M.; Schofield, E.A.; Stabler, C.L. Layer-by-Layer Cerium Oxide Nanoparticle Coating for Antioxidant Protection of Encapsulated Beta Cells. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1801493.

- Ghostine, R.A.; Jisr, R.M.; Lehaf, A.; Schlenoff, J.B. Roughness and Salt Annealing in a Polyelectrolyte Multilayer. Langmuir 2013, 29, 11742–11750.

- Buron, C.C.; Filiâtre, C.; Membrey, F.; Bainier, C.; Buisson, L.; Charraut, D.; Foissy, A. Surface morphology and thickness of a multilayer film composed of strong and weak polyelectrolytes: Effect of the number of adsorbed layers, concentration and type of salts. Thin Solid Films 2009, 517, 2611–2617.

- Lavalle, P.; Gergely, C.; Cuisinier, F.J.G.; Decher, G.; Schaaf, P.; Voegel, J.C.; Picart, C. Comparison of the Structure of Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Films Exhibiting a Linear and an Exponential Growth Regime: An in Situ Atomic Force Microscopy Study. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 4458–4465.

- Campbell, J.; Vikulina, A.S. Layer-By-Layer Assemblies of Biopolymers: Build-Up, Mechanical Stability and Molecular Dynamics. Polymers (Basel). 2020, 12, 1949.

- Mzyk, A.; Lackner, J.M.; Wilczek, P.; Lipińska, L.; Niemiec-Cyganek, A.; Samotus, A.; Morenc, M. Polyelectrolyte multilayer film modification for chemo-mechano-regulation of endothelial cell response. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 8811–8828.

- Schneider, A.; Francius, G.; Obeid, R.; Schwinté, P.; Hemmerlé, J.; Frisch, B.; Schaaf, P.; Voegel, J.-C.; Senger, B.; Picart, C. Polyelectrolyte Multilayers with a Tunable Young’s Modulus: Influence of Film Stiffness on Cell Adhesion. Langmuir 2006, 22, 1193–1200.

- Schmidt, S.; Madaboosi, N.; Uhlig, K.; Köhler, D.; Skirtach, A.; Duschl, C.; Möhwald, H.; Volodkin, D. V. Control of cell adhesion by mechanical reinforcement of soft polyelectrolyte films with nanoparticles. Langmuir 2012, 28, 7249–7257.

- Abalymov, A.A.; Parakhonskiy, B. V.; Skirtach, A.G. Colloids-at-surfaces: physicochemical approaches for facilitating cell adhesion on hybrid hydrogels. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 125185.

- Kovačević, D.; Pratnekar, R.; Godič Torkar, K.; Salopek, J.; Dražić, G.; Abram, A.; Bohinc, K. Influence of Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Properties on Bacterial Adhesion Capacity. Polymers (Basel). 2016, 8, 345.

- Guo, S.; Kwek, M.Y.; Toh, Z.Q.; Pranantyo, D.; Kang, E.-T.; Loh, X.J.; Zhu, X.; Jańczewski, D.; Neoh, K.G. Tailoring Polyelectrolyte Architecture To Promote Cell Growth and Inhibit Bacterial Adhesion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 7882–7891.

- Carvalho, A.L.; Vale, A.C.; Sousa, M.P.; Barbosa, A.M.; Torrado, E.; Mano, J.F.; Alves, N.M. Antibacterial bioadhesive layer-by-layer coatings for orthopedic applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 5385–5393.

- Abalymov, A.A.; Van Der Meeren, L.; Saveleva, M.; Prikhozhdenko, E.; Dewettinck, K.; Parakhonskiy, B.; Skirtach, A.G. Cells-Grab-on Particles: A Novel Approach to Control Cell Focal Adhesion on Hybrid Thermally Annealed Hydrogels. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 3933–3944.

- Abalymov, A.A.; Parakhonskiy, B.; Skirtach, A.G. Polymer- and Hybrid-Based Biomaterials for Interstitial, Connective, Vascular, Nerve, Visceral and Musculoskeletal Tissue Engineering. Polymers (Basel). 2020, 12, 620.

- Kolesnikova, T.A.; Kohler, D.; Skirtach, A.G.; Möhwald, H. Laser-Induced Cell Detachment, Patterning, and Regrowth on Gold Nanoparticle Functionalized Surfaces. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 9585–9595.

- Bai, J.; Zuo, X.; Feng, X.; Sun, Y.; Ge, Q.; Wang, X.; Gao, C. Dynamic Titania Nanotube Surface Achieves UV-Triggered Charge Reversal and Enhances Cell Differentiation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 36939–36948.

- Xing, R.; Jiao, T.; Ma, K.; Ma, G.; Möhwald, H.; Yan, X. Regulating Cell Apoptosis on Layer-by-Layer Assembled Multilayers of Photosensitizer-Coupled Polypeptides and Gold Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26506.

- Skirtach, A.G.; Volodkin, D. V.; Möhwald, H. Bio-interfaces-Interaction of PLL/HA Thick Films with Nanoparticles and Microcapsules. ChemPhysChem 2010, 11, 822–829.

- de Gennes, P.-G. Soft Matter (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. English 1992, 31, 842–845.

- Skorb, E. V.; Möhwald, H. 25th Anniversary Article: Dynamic Interfaces for Responsive Encapsulation Systems. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 5029–5043.

- Li, J.; Gao, W.; Dong, R.; Pei, A.; Sattayasamitsathit, S.; Wang, J. Nanomotor lithography. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5026.

- Guix, M.; Meyer, A.K.; Koch, B.; Schmidt, O.G. Carbonate-based Janus micromotors moving in ultra-light acidic environment generated by HeLa cells in situ. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21701.

- Dong, R.; Li, J.; Rozen, I.; Ezhilan, B.; Xu, T.; Christianson, C.; Gao, W.; Saintillan, D.; Ren, B.; Wang, J. Vapor-Driven Propulsion of Catalytic Micromotors. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13226.

- Shchukin, D.G.D.G.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Yasakau, K. a.; Lamaka, S.; Ferreira, M.G.S.M.G.S.; Möhwald, H. Layer-by-Layer Assembled Nanocontainers for Self-Healing Corrosion Protection. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 1672–1678.

- Andreeva, D. V.; Fix, D.; M¨︁ohwald, H.; Shchukin, D.G. Self-Healing Anticorrosion Coatings Based on pH-Sensitive Polyelectrolyte/Inhibitor Sandwichlike Nanostructures. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 2789–2794.

- Tong, W.; Song, X.; Gao, C. Layer-by-layer assembly of microcapsules and their biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 6103–6124.

- Vergaro, V.; Scarlino, F.; Bellomo, C.; Rinaldi, R.; Vergara, D.; Maffia, M.; Baldassarre, F.; Giannelli, G.; Zhang, X.; Lvov, Y.M.; et al. Drug-loaded polyelectrolyte microcapsules for sustained targeting of cancer cells. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 63, 847–864.

- Zhao, T.; Chen, L.; Wang, P.; Li, B.; Lin, R.; Abdulkareem Al-Khalaf, A.; Hozzein, W.N.; Zhang, F.; Li, X.; Zhao, D. Surface-kinetics mediated mesoporous multipods for enhanced bacterial adhesion and inhibition. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4387.

- Ling, X.Y.; Phang, I.Y.; Acikgoz, C.; Yilmaz, M.D.; Hempenius, M.A.; Vancso, G.J.; Huskens, J. Janus Particles with Controllable Patchiness and Their Chemical Functionalization and Supramolecular Assembly. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7677–7682.

- Pawar, A.B.; Kretzschmar, I. Fabrication, Assembly, and Application of Patchy Particles. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2010, 31, 150–168.

- Yoshida, M.; Roh, K.-H.; Mandal, S.; Bhaskar, S.; Lim, D.; Nandivada, H.; Deng, X.; Lahann, J. Structurally Controlled Bio-hybrid Materials Based on Unidirectional Association of Anisotropic Microparticles with Human Endothelial Cells. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 4920–4925.

- Chen, R.T.; Muir, B.W.; Such, G.K.; Postma, A.; McLean, K.M.; Caruso, F. Fabrication of asymmetric “Janus” particles via plasma polymerization. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 5121–5123.

- Paunov, V.N.; Cayre, O.J. Supraparticles and“Janus” Particles Fabricated by Replication of Particle Monolayers at Liquid Surfaces Using a Gel Trapping Technique. Adv. Mater. 2004, 16, 788–791.

- Li, Z.; Lee, D.; Rubner, M.F.; Cohen, R.E. Layer-by-Layer Assembled Janus Microcapsules. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 7876–7879.

- Cui, J.-Q.; Kretzschmar, I. Surface-Anisotropic Polystyrene Spheres by Electroless Deposition. Langmuir 2006, 22, 8281–8284.

- Kohler, D.; Madaboosi, N.; Delcea, M.; Schmidt, S.; De Geest, B.G.; Volodkin, D. V.; Möhwald, H.; Skirtach, A.G. Patchiness of embedded particles and film stiffness control through concentration of gold nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 1095–1100.

- Xu, W.; Rudov, A.; Oppermann, A.; Wypysek, S.; Kather, M.; Schroeder, R.; Richtering, W.; Potemkin, I.I.; Wöll, D.; Pich, A. Synthesis of Polyampholyte Janus-like Microgels by Coacervation of Reactive Precursors in Precipitation Polymerization. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1248–1255.

- Kobaku, S.P.R.; Snyder, C.S.; Karunakaran, R.G.; Kwon, G.; Wong, P.; Tuteja, A.; Mehta, G. Wettability Engendered Templated Self-Assembly (WETS) for the Fabrication of Biocompatible, Polymer–Polyelectrolyte Janus Particles. ACS Macro Lett. 2019, 8, 1491–1497.

- Ji, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, D.; Zhou, C.; Wu, Y.; He, Q. Continuously Variable Regulation of the Speed of Bubble-Propelled Janus Microcapsule Motors Based on Salt-Responsive Polyelectrolyte Brushes. Chem.—An. Asian J. 2019, 14, 2450–2455.

- Shao, J.; Abdelghani, M.; Shen, G.; Cao, S.; Williams, D.S.; van Hest, J.C.M. Erythrocyte Membrane Modified Janus Polymeric Motors for Thrombus Therapy. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 4877–4885.

- Wu, Y.; Lin, X.; Wu, Z.; Möhwald, H.; He, Q. Self-Propelled Polymer Multilayer Janus Capsules for Effective Drug Delivery and Light-Triggered Release. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 10476–10481.

- Wu, Y.; Si, T.; Lin, X.; He, Q. Near infrared-modulated propulsion of catalytic Janus polymer multilayer capsule motors. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 511–514.

- Yoshizumi, Y.; Suzuki, H. Self-Propelled Metal–Polymer Hybrid Micromachines with Bending and Rotational Motions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 21355–21361.

- Marschelke, C.; Raguzin, I.; Matura, A.; Fery, A.; Synytska, A. Controlled and tunable design of polymer interface for immobilization of enzymes: does curvature matter? Soft Matter 2017, 13, 1074–1084.

- Lin, Z.; Wu, Z.; Lin, X.; He, Q. Catalytic Polymer Multilayer Shell Motors for Separation of Organics. Chem. - A Eur. J. 2016, 22, 1587–1591.

- Hu, N.; Zhang, B.; Gai, M.; Zheng, C.; Frueh, J.; He, Q. Forecastable and Guidable Bubble-Propelled Microplate Motors for Cell Transport. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2017, 38, 1600795.

- Gilbert, J.B.; O’Brien, J.S.; Suresh, H.S.; Cohen, R.E.; Rubner, M.F. Orientation-Specific Attachment of Polymeric Microtubes on Cell Surfaces. Adv. Mater. 2013, 5948–5952.

- He, W.; Frueh, J.; Wu, Z.; He, Q. Leucocyte Membrane-Coated Janus Microcapsules for Enhanced Photothermal Cancer Treatment. Langmuir 2016, 32, 3637–3644.

- He, W.; Frueh, J.; Wu, Z.; He, Q. How Leucocyte Cell Membrane Modified Janus Microcapsules are Phagocytosed by Cancer Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 4407–4415.

- He, W.; Frueh, J.; Hu, N.; Liu, L.; Gai, M.; He, Q. Guidable Thermophoretic Janus Micromotors Containing Gold Nanocolorifiers for Infrared Laser Assisted Tissue Welding. Adv. Sci. 2016, 3, 1600206.

- Volodkin, D.; Skirtach, A.; Möhwald, H. Bioapplications of light-sensitive polymer films and capsules assembled using the layer-by-layer technique. Polym. Int. 2012, 61, 673–679.

- Andreeva, D. V.; Skorb, E. V.; Shchukin, D.G. Layer-by-Layer Polyelectrolyte/Inhibitor Nanostructures for Metal Corrosion Protection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2010, 2, 1954–1962.

- Andreeva, D. V.; Fix, D.; Möhwald, H.; Shchukin, D.G. Buffering polyelectrolyte multilayers for active corrosion protection. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 1738–1740.

- Haneder, S.; Da Como, E.; Feldmann, J.; Lupton, J.M.; Lennartz, C.; Erk, P.; Fuchs, E.; Molt, O.; Münster, I.; Schildknecht, C.; et al. Controlling the Radiative Rate of Deep-Blue Electrophosphorescent Organometallic Complexes by Singlet-Triplet Gap Engineering. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 3325–3330.

- Grigoriev, D.O.; Köhler, K.; Skorb, E.; Shchukin, D.G.; Möhwald, H. Polyelectrolyte complexes as a “smart” depot for self-healing anticorrosion coatings. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 1426–1432.

- Skorb, E. V.; Skirtach, A.G.; Sviridov, D. V.; Shchukin, D.G.; Möhwald, H. Laser-Controllable Coatings for Corrosion Protection. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 1753–1760.

- Jafari, A.H.; Hosseini, S.M.A.; Jamalizadeh, E. Investigation of Smart Nanocapsules Containing Inhibitors for Corrosion Protection of Copper. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 9004–9009.

- Kopeć, M.; Szczepanowicz, K.; Mordarski, G.; Podgórna, K.; Socha, R.P.; Nowak, P.; Warszyński, P.; Hack, T. Self-healing epoxy coatings loaded with inhibitor-containing polyelectrolyte nanocapsules. Prog. Org. Coatings 2015, 84, 97–106.

- Zhao, X.; Yuan, S.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, B.; Liu, N.; Chen, S.; Liu, S.; Sun, X.; Duan, J. Perfect Combination of LBL with Sol–Gel Film to Enhance the Anticorrosion Performance on Al Alloy under Simulated and Accelerated Corrosive Environment. Materials (Basel). 2019, 13, 111.

- Fan, F.; Zhou, C.; Wang, X.; Szpunar, J. Layer-by-Layer Assembly of a Self-Healing Anticorrosion Coating on Magnesium Alloys. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 27271–27278.

- Skorb, E. V.; Sviridov, D. V.; Möhwald, H.; Shchukin, D.G. Light responsive protective coatings. Chem. Commun. 2009, 6041–6043.

- Skorb, E. V.; Fix, D.; Andreeva, D. V.; Möhwald, H.; Shchukin, D.G. Surface-Modified Mesoporous SiO2 Containers for Corrosion Protection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 2373–2379.

- Skorb, E. V.; Shchukin, D.G.; Möhwald, H.; Sviridov, D. V. Photocatalytically-active and photocontrollable coatings based on titania-loaded hybrid sol–gel films. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 4931–4937.

- Ulasevich, S.A.; Brezesinski, G.; Möhwald, H.; Fratzl, P.; Schacher, F.H.; Poznyak, S.K.; Andreeva, D. V.; Skorb, E. V. Light-Induced Water Splitting Causes High-Amplitude Oscillation of pH-Sensitive Layer-by-Layer Assemblies on TiO2. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 13001–13004.

- Maltanava, H.M.; Poznyak, S.K.; Andreeva, D. V.; Quevedo, M.C.; Bastos, A.C.; Tedim, J.; Ferreira, M.G.S.; Skorb, E. V. Light-Induced Proton Pumping with a Semiconductor: Vision for Photoproton Lateral Separation and Robust Manipulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 24282–24289.

- Ryzhkov, N. V.; Skorb, E. V. A platform for light-controlled formation of free-stranding lipid membranes. J. R. Soc. Interface 2020, 17, 20190740.

- Fenoy, G.E.; Maza, E.; Zelaya, E.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Layer-by-layer assemblies of highly connected polyelectrolyte capped-Pt nanoparticles for electrocatalysis of hydrogen evolution reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 416, 24–32.

- Skorb, E.V.; Antonouskaya, L.I.; Belyasova, N.A.; Shchukin, D.G.; Möhwald, H.; Sviridov, D.V. Antibacterial activity of thin-film photocatalysts based on metal-modified TiO2 and TiO2:In2O3 nanocomposite. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2008, 84, 94–99.

- Lanchuk, Y.; Nikitina, A.; Brezhneva, N.; Ulasevich, S.A.; Semenov, S.N.; Skorb, E. V. Photocatalytic Regulation of an Autocatalytic Wave of Spatially Propagating Enzymatic Reactions. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 1798–1803.

- Nikitina, A.A.; Ulasevich, S.A.; Kassirov, I.S.; Bryushkova, E.A.; Koshel, E.I.; Skorb, E. V. Nanostructured Layer-by-Layer Polyelectrolyte Containers to Switch Biofilm Fluorescence. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 3793–3799.

- Ryzhkov, N. V.; Yurova, V.Y.; Ulasevich, S.A.; Skorb, E. V. Photoelectrochemical photocurrent switching effect on a pristine anodized Ti/TiO 2 system as a platform for chemical logic devices. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 12355–12359.

- Lanchuk, Y. V.; Ulasevich, S.A.; Fedotova, T.A.; Kolpashchikov, D.M.; Skorb, E. V. Towards sustainable diagnostics: replacing unstable H2O2 by photoactive TiO2 in testing systems for visible and tangible diagnostics for use by blind people. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 37735–37739.

- Stekolshchikova, A.A.; Radaev, A. V.; Orlova, O.Y.; Nikolaev, K.G.; Skorb, E. V. Thin and Flexible Ion Sensors Based on Polyelectrolyte Multilayers Assembled onto the Carbon Adhesive Tape. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 15421–15427.

- Nikolaev, K.G.; Kalmykov, E. V.; Shavronskaya, D.O.; Nikitina, A.A.; Stekolshchikova, A.A.; Kosareva, E.A.; Zenkin, A.A.; Pantiukhin, I.S.; Orlova, O.Y.; Skalny, A. V.; et al. ElectroSens Platform with a Polyelectrolyte-Based Carbon Fiber Sensor for Point-of-Care Analysis of Zn in Blood and Urine. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 18987–18994.

- Andreeva, D. V.; Sviridov, D. V.; Masic, A.; Möhwald, H.; Skorb, E. V. Nanoengineered Metal Surface Capsules: Construction of a Metal-Protection System. Small 2012, 8, 820–825.

- Gensel, J.; Borke, T.; Pérez, N.P.; Fery, A.; Andreeva, D. V.; Betthausen, E.; Müller, A.H.E.; Möhwald, H.; Skorb, E. V. Cavitation Engineered 3D Sponge Networks and Their Application in Active Surface Construction. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 985–989.

- Rivero, P.J.; Goicoechea, J.; Hernaez, M.; Socorro, A.B.; Matias, I.R.; Arregui, F.J. Optical fiber resonance-based pH sensors using gold nanoparticles into polymeric layer-by-layer coatings. Microsyst. Technol. 2016, 22, 1821–1829.

- Tokarev, I.; Tokareva, I.; Minko, S. Optical Nanosensor Platform Operating in Near-Physiological pH Range via Polymer-Brush-Mediated Plasmon Coupling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 143–146.

- Kozlovskaya, V.; Kharlampieva, E.; Khanal, B.P.; Manna, P.; Zubarev, E.R.; Tsukruk, V. V. Ultrathin Layer-by-Layer Hydrogels with Incorporated Gold Nanorods as pH-Sensitive Optical Materials. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 7474–7485.

- de Oliveira, R.D.; Calaça, G.N.; Santos, C.S.; Fujiwara, S.T.; Pessôa, C.A. Preparation, characterization and electrochemistry of Layer-by-Layer films of silver nanoparticles and silsesquioxane polymer. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 509, 638–647.

- Irigoyen, J.; Laakso, T.; Politakos, N.; Dahne, L.; Pihlajamäki, A.; Mänttäri, M.; Moya, S.E. Design and Performance Evaluation of Hybrid Nanofiltration Membranes Based on Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes and Polyelectrolyte Multilayers for Larger Ion Rejection and Separation. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2016, 217, 804–811.

- Stanojev, J.; Bajac, B.; Cvejic, Z.; Matovic, J.; Srdic, V. V. Development of MWCNT thin film electrode transparent in the mid-IR range. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 11340–11345.

- Barsan, M.M.; Brett, C.M.A. Recent advances in layer-by-layer strategies for biosensors incorporating metal nanoparticles. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 79, 286–296.

- McShane, M.; Ritter, D. Microcapsules as optical biosensors. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 8189–8193.

- Sukhorukov, G.B.; Rogach, A.L.; Garstka, M.; Springer, S.; Parak, W.J.; Muñoz-Javier, A.; Kreft, O.; Skirtach, A.G.; Susha, A.S.; Ramaye, Y.; et al. Multifunctionalized polymer microcapsules: novel tools for biological and pharmacological applications. Small 2007, 3, 944–955.

- Van der Meeren, L.; Li, J.; Parakhonskiy, B. V.; Krysko, D. V.; Skirtach, A.G. Classification of analytics, sensorics, and bioanalytics with polyelectrolyte multilayer capsules. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 5015–5029.

- Wu, X.; Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Tang, N. Layer-by-Layer Deposition of Hyaluronan and Quercetin-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles onto Titanium for Improving Blood Compatibility. Coatings 2020, 10, 256.

- Sydow, S.; de Cassan, D.; Hänsch, R.; Gengenbach, T.R.; Easton, C.D.; Thissen, H.; Menzel, H. Layer-by-layer deposition of chitosan nanoparticles as drug-release coatings for PCL nanofibers. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 233–246.

- Campos, P.P.; Dunne, A.; Delaney, C.; Moloney, C.; Moulton, S.E.; Benito-Lopez, F.; Ferreira, M.; Diamond, D.; Florea, L. Photoswitchable Layer-by-Layer Coatings Based on Photochromic Polynorbornenes Bearing Spiropyran Side Groups. Langmuir 2018, 34, 4210–4216.

- Rouster, P.; Dondelinger, M.; Galleni, M.; Nysten, B.; Jonas, A.M.; Glinel, K. Layer-by-layer assembly of enzyme-loaded halloysite nanotubes for the fabrication of highly active coatings. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2019, 178, 508–514.

- Semiconductor Nanocrystal Quantum Dots; Rogach, A.L., Ed.; Springer Vienna: Vienna, 2008; ISBN 978-3-211-75235-7.

- Abd. Rahman, S.; Ariffin, N.; Yusof, N.; Abdullah, J.; Mohammad, F.; Ahmad Zubir, Z.; Nik Abd. Aziz, N. Thiolate-Capped CdSe/ZnS Core-Shell Quantum Dots for the Sensitive Detection of Glucose. Sensors 2017, 17, 1537.

- Bae, W.K.; Kwak, J.; Lim, J.; Lee, D.; Nam, M.K.; Char, K.; Lee, C.; Lee, S. Multicolored Light-Emitting Diodes Based on All-Quantum-Dot Multilayer Films Using Layer-by-Layer Assembly Method. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 2368–2373.

- Jaffar, S.; Nam, K.T.; Khademhosseini, A.; Xing, J.; Langer, R.S.; Belcher, A.M. Layer-by-Layer Surface Modification and Patterned Electrostatic Deposition of Quantum Dots. Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 1421–1425.

- Nagaraja, A.T.; Sooresh, A.; Meissner, K.E.; McShane, M.J. Processing and Characterization of Stable, pH-Sensitive Layer-by-Layer Modified Colloidal Quantum Dots. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 6194–6202.

- Zimnitsky, D.; Jiang, C.; Xu, J.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, L.; Tsukruk, V. V. Photoluminescence of a Freely Suspended Monolayer of Quantum Dots Encapsulated into Layer-by-Layer Films. Langmuir 2007, 23, 10176–10183.

- Constantine, C.A.; Gattás-Asfura, K.M.; Mello, S. V.; Crespo, G.; Rastogi, V.; Cheng, T.-C.; DeFrank, J.J.; Leblanc, R.M. Layer-by-Layer Biosensor Assembly Incorporating Functionalized Quantum Dots. Langmuir 2003, 19, 9863–9867.

- Xiao, F.-X.; Miao, J.; Liu, B. Layer-by-Layer Self-Assembly of CdS Quantum Dots/Graphene Nanosheets Hybrid Films for Photoelectrochemical and Photocatalytic Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 1559–1569.

- Nifontova, G.; Ramos-Gomes, F.; Baryshnikova, M.; Alves, F.; Nabiev, I.; Sukhanova, A. Cancer Cell Targeting With Functionalized Quantum Dot-Encoded Polyelectrolyte Microcapsules. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 34.

- Nifontova, G.; Efimov, A.; Agapova, O.; Agapov, I.; Nabiev, I.; Sukhanova, A. Bioimaging Tools Based on Polyelectrolyte Microcapsules Encoded with Fluorescent Semiconductor Nanoparticles: Design and Characterization of the Fluorescent Properties. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 29.

- Adamczak, M.; Hoel, H.J.; Gaudernack, G.; Barbasz, J.; Szczepanowicz, K.; Warszyński, P. Polyelectrolyte multilayer capsules with quantum dots for biomedical applications. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2012, 90, 211–216.

- Rogach, A.L.; Kotov, N.A.; Koktysh, D.S.; Susha, A.S.; Caruso, F. II–VI semiconductor nanocrystals in thin films and colloidal crystals. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2002, 202, 135–144.

- Wang, D.; Rogach, A.L.; Caruso, F. Semiconductor Quantum Dot-Labeled Microsphere Bioconjugates Prepared by Stepwise Self-Assembly. Nano Lett. 2002, 2, 857–861.

- Hashimoto, M.; Feng, J.; York, R.L.; Ellerbee, A.K.; Morrison, G.; Thomas III, S.W.; Mahadevan, L.; Whitesides, G.M. Infochemistry: Encoding Information as Optical Pulses Using Droplets in a Microfluidic Device. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 12420–12429.

- Ryzhkov, N. V.; Andreeva, D. V.; Skorb, E. V. Coupling pH-Regulated Multilayers with Inorganic Surfaces for Bionic Devices and Infochemistry. Langmuir 2019, 35, 8543–8556.

- Han, M.; Gao, X.; Su, J.Z.; Nie, S. Quantum-dot-tagged microbeads for multiplexed optical coding of biomolecules. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 631–635.

- Pinchasik, B.-E.; Tauer, K.; Möhwald, H.; Skirtach, A.G. Polymer Brush Gradients by Adjusting the Functional Density Through Temperature Gradient. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 1, 1300056.

- Sailer, M.; Barrett, C.J. Fabrication of Two-Dimensional Gradient Layer-by-Layer Films for Combinatorial Biosurface Studies. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 5704–5711.

- Ariga, K.; Ahn, E.; Park, M.; Kim, B. Layer-by-Layer Assembly: Recent Progress from Layered Assemblies to Layered Nanoarchitectonics. Chem.—An. Asian J. 2019, 14, 2553–2566.

- Yu, A.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Han, D.; Knight, A.R. Preparation and electrochemical properties of gold nanoparticles containing carbon nanotubes-polyelectrolyte multilayer thin films. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 9015–9019.

- Vallés, C.; Zhang, X.; Cao, J.; Lin, F.; Young, R.J.; Lombardo, A.; Ferrari, A.C.; Burk, L.; Mülhaupt, R.; Kinloch, I.A. Graphene/Polyelectrolyte Layer-by-Layer Coatings for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 5272–5281.

- Liu, H.; Bandyopadhyay, P.; Kshetri, T.; Kim, N.H.; Ku, B.-C.; Moon, B.; Lee, J.H. Layer-by-layer assembled polyelectrolyte-decorated graphene multilayer film for hydrogen gas barrier application. Compos. Part. B Eng. 2017, 114, 339–347.

- Kurapati, R.; Raichur, A.M. Graphene oxide based multilayer capsules with unique permeability properties: facile encapsulation of multiple drugs. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 6013–6015.

- Ermakov, A.; Lim, S.H.; Gorelik, S.; Kauling, A.P.; de Oliveira, R.V.B.; Castro Neto, A.H.; Glukhovskoy, E.; Gorin, D.A.; Sukhorukov, G.B.; Kiryukhin, M. V. Polyelectrolyte-Graphene Oxide Multilayer Composites for Array of Microchambers which are Mechanically Robust and Responsive to NIR Light. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2019, 40, 1700868.

- Pan, H.; Lu, Y.; Song, L.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Y. Construction of layer-by-layer coating based on graphene oxide/β-FeOOH nanorods and its synergistic effect on improving flame retardancy of flexible polyurethane foam. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2016, 129, 116–122.

- Gao, H.; Qi, X.; Chen, Y.; Sun, W. Electrochemical deoxyribonucleic acid biosensor based on the self-assembly film with nanogold decorated on ionic liquid modified carbon paste electrode. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 704, 133–138.

- Wu, X.; Chai, Y.; Yuan, R.; Su, H.; Han, J. A novel label-free electrochemical microRNA biosensor using Pd nanoparticles as enhancer and linker. Analyst 2013, 138, 1060–1066.

- Erokhina, S.; Ricci, V.; Iannotta, S.; Erokhin, V. Modification of the porous glass filter with LbL technique for variable filtration applications. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 606, 125459.

- Saveleva, M.S.; Lengert, E. V.; Gorin, D.A.; Parakhonskiy, B. V.; Skirtach, A.G. Polymeric and Lipid Membranes—From Spheres to Flat Membranes and vice versa. Membranes (Basel). 2017, 7, 44.

- Egueh, A.-N.D.; Lakard, B.; Fievet, P.; Lakard, S.; Buron, C. Charge properties of membranes modified by multilayer polyelectrolyte adsorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 344, 221–227.

- Lvov, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Fakhrullin, R. Halloysite Clay Nanotubes for Loading and Sustained Release of Functional Compounds. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 1227–1250.

- Konnova, S.A.; Sharipova, I.R.; Demina, T.A.; Osin, Y.N.; Yarullina, D.R.; Ilinskaya, O.N.; Lvov, Y.M.; Fakhrullin, R.F. Biomimetic cell-mediated three-dimensional assembly of halloysite nanotubes. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 4208–4210.