| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sirius Huang | -- | 1403 | 2022-11-11 01:35:10 |

Video Upload Options

In celestial mechanics the specific relative angular momentum [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{h} }[/math] plays a pivotal role in the analysis of the two-body problem. One can show that it is a constant vector for a given orbit under ideal conditions. This essentially proves Kepler's second law. It's called specific angular momentum because it's not the actual angular momentum [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{L} }[/math], but the angular momentum per mass. Thus, the word "specific" in this term is short for "mass-specific" or divided-by-mass: Thus the SI unit is: m2·s−1. [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] denotes the reduced mass [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{m} = \frac{1}{m_1}+\frac{1}{m_2} }[/math].

1. Definition

The specific relative angular momentum is defined as the cross product of the relative position vector [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} }[/math] and the relative velocity vector [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{v} }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{h} = \vec{r}\times \vec{v} = \frac{\vec{L}}{m} }[/math]

The [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{h} }[/math] vector is always perpendicular to the instantaneous osculating orbital plane, which coincides with the instantaneous perturbed orbit. It would not necessarily be perpendicular to an average plane which accounted for many years of perturbations.

As usual in physics, the magnitude of the vector quantity [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{h} }[/math] is denoted by [math]\displaystyle{ h }[/math]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ h = \left \| \vec{h} \right \| }[/math]

2. Proof That the Specific Relative Angular Momentum Is Constant under Ideal Conditions

2.1. Prerequisites

The following is only valid under the simplifications also applied to Newton's law of universal gravitation.

One looks at two point masses [math]\displaystyle{ m_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ m_2 }[/math], at the distance [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] from one another and with the gravitational force [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{F} = G\frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}\frac{\vec{r}}{r} }[/math] acting between them. This force acts instantly, over any distance and is the only force present. The coordinate system is inertial.

The further simplification [math]\displaystyle{ m_1 \gg m_2 }[/math] is assumed in the following. Thus [math]\displaystyle{ m_1 }[/math] is the central body in the origin of the coordinate system and [math]\displaystyle{ m_2 }[/math] is the satellite orbiting around it. Now the reduced mass is also equal to [math]\displaystyle{ m_2 }[/math] and the equation of the two-body problem is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ddot{\vec{r}} = -\frac{\mu}{r^2}\frac{\vec{r}}{r} }[/math]

with the standard gravitational parameter [math]\displaystyle{ \mu = Gm_1 }[/math] and the distance vector [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} }[/math] (absolute value [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math]) that points from the origin (central body) to the satellite, because of its negligible mass.[1]

It is important not to confound the gravitational parameter [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math] with the reduced mass, which is sometimes also denoted by the same letter [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math].

2.2. Proof

One obtains the specific relative angular momentum by multiplying (cross product) the equation of the two-body problem with the distance vector [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} \times \ddot{\vec{r}} = - \vec{r} \times \frac{\mu}{r^2}\frac{\vec{r}}{r} }[/math]

The cross product of a vector with itself (right hand side) is 0. The left hand side simplifies to

- [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} \times \ddot{\vec{r}} = \dot{\vec{r}} \times \dot{\vec{r}} + \vec{r} \times \ddot{\vec{r}} = \frac{\mathrm{d} \left(\vec{r}\times\dot{\vec{r}}\right) }{\mathrm{d}t} = 0 }[/math]

according to the product rule of differentiation.

This means that [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r}\times\dot{\vec{r}} }[/math] is constant (i.e., a conserved quantity). And this is exactly the angular momentum per mass of the satellite:[2]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{h} = \vec{r}\times\dot{\vec{r}} \text{ is const.} }[/math]

This vector is perpendicular to the orbit plane, the orbit remains in this plane because the angular momentum is constant.

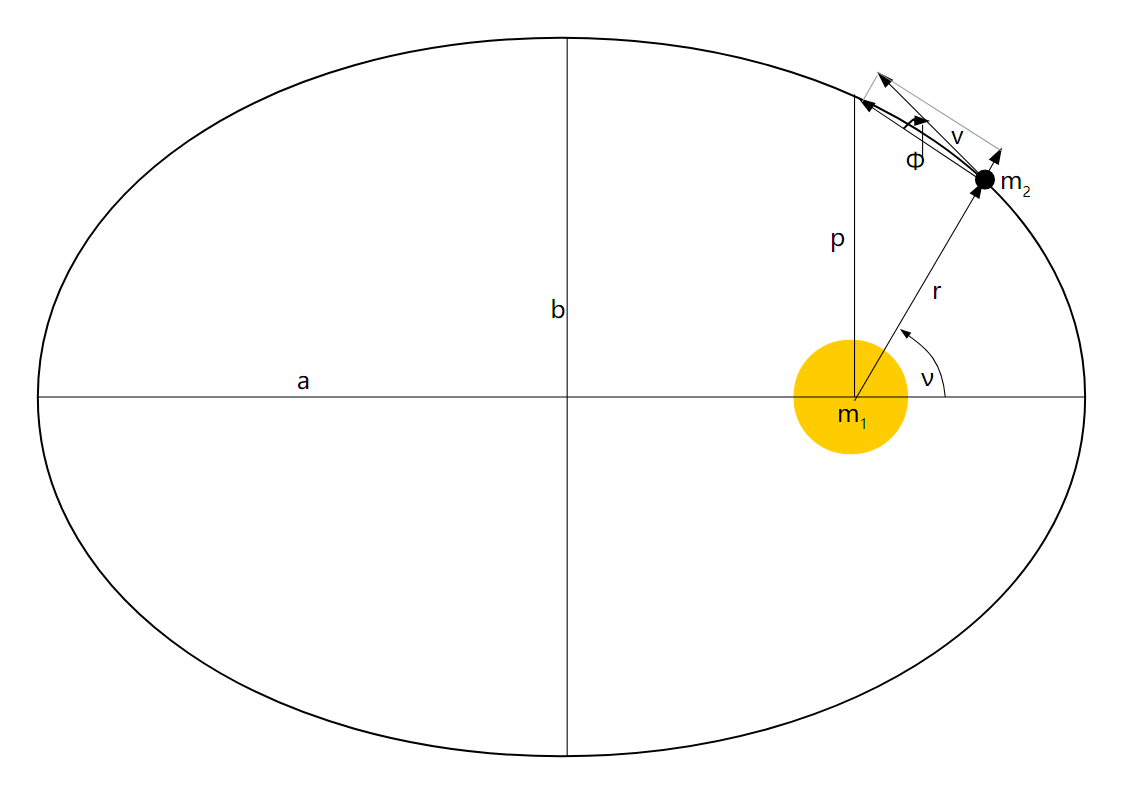

One can obtain further insight into the two-body problem with the definitions of the flight path angle [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] and the transversal and radial component of the velocity vector (see illustration on the right). The next three formulas are all equivalent possibilities to calculate the absolute value of the specific relative angular momentum vector

- [math]\displaystyle{ h = rv\cos\phi }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ h = r^2\dot{\theta} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ h = \sqrt{\mu p} }[/math]

Where [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] is called the semi-latus rectum of the curve.

3. Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion

Kepler's laws of planetary motion can be proved almost directly with the above relationships.

3.1. First Law

The proof starts again with the equation of the two-body problem. This time one multiplies it (cross product) with the specific relative angular momentum

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ddot{\vec{r}} \times \vec{h} = - \frac{\mu}{r^2}\frac{\vec{r}}{r} \times \vec{h} }[/math]

The left hand side is equal to the derivative [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}t} \left(\dot{\vec{r}}\times\vec{h}\right) }[/math] because the angular momentum is constant.

After some steps the right hand side becomes:

- [math]\displaystyle{ -\frac{\mu}{r^3}\left(\vec{r} \times \vec{h}\right) = -\frac{\mu}{r^3} \left(\left(\vec{r}\cdot\vec{v}\right)\vec{r} - r^2\vec{v}\right) = -\left(\frac{\mu}{r^2}\dot{r}\vec{r} - \frac{\mu}{r}\vec{v}\right) = \mu \frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}t}\left(\frac{\vec{r}}{r}\right) }[/math]

Setting these two expression equal and integrating over time leads to (with the constant of integration [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{C} }[/math])

- [math]\displaystyle{ \dot{\vec{r}}\times\vec{h} = \mu\frac{\vec{r}}{r} + \vec{C} }[/math]

Now this equation is multiplied (dot product) with [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} }[/math] and rearranged

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \vec{r} \cdot \left(\dot{\vec{r}}\times\vec{h}\right) &= \vec{r} \cdot \left(\mu\frac{\vec{r}}{r} + \vec{C}\right) \\ \Rightarrow{} \left(\vec{r}\times\dot{\vec{r}}\right) \cdot \vec{h} &= \mu r + rC\cos\theta \\ \Rightarrow{} h^2 &= \mu r + rC\cos\theta \end{align} }[/math]

Finally one gets the orbit equation [3]

- [math]\displaystyle{ r = \frac{\frac{h^2}{\mu}}{1 + \frac{C}{\mu}\cos\theta} }[/math]

which is the equation of a conic section in polar coordinates with semi-latus rectum [math]\displaystyle{ p = \frac{h^2}{\mu} }[/math] and eccentricity [math]\displaystyle{ e = \frac{C}{\mu} }[/math]. This proves Kepler's first law, in words:

The orbit of a planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one focus.

3.2. Second Law

The second law follows instantly from the second of the three equations to calculate the absolute value of the specific relative angular momentum.

If one connects this form of the equation [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}t = \frac{r^2}{h} \ \mathrm{d}\theta }[/math] with the relationship [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}A = \frac{r^2}{2} \ \mathrm{d}\theta }[/math] for the area of a sector with an infinitesimal small angle [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}\theta }[/math] (triangle with one very small side), the equation [4]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}t = \frac{2}{h}\ \mathrm{d}A }[/math]

comes out, that is the mathematical formulation of the words:

The line joining the planet to the Sun sweeps out equal areas in equal times.

3.3. Third Law

Kepler's third is a direct consequence of the second law. Integrating over one revolution gives the orbital period

- [math]\displaystyle{ T = \frac{2\pi ab}{h} }[/math]

for the area [math]\displaystyle{ \pi ab }[/math] of an ellipse. Replacing the semi-minor axis with [math]\displaystyle{ b=\sqrt{ap} }[/math] and the specific relative angular momentum with [math]\displaystyle{ h = \sqrt{\mu p} }[/math] one gets [4]

- [math]\displaystyle{ T = 2\pi \sqrt{\frac{a^3}{\mu}} }[/math]

There is thus a relationship between the semi-major axis and the orbital period of a satellite that can be reduced to a constant of the central body. This is the same as the famous formulation of the law:

The square of the period of a planet is proportional to the cube of its mean distance to the Sun.

References

- The derivation of the specific angular momentum works also if one does not make this assumption. Then the gravitational parameter is [math]\displaystyle{ \mu = G\left(m_1 + m_2\right) }[/math].

- Vallado, David Anthony (2001). Fundamentals of Astrodynamics and Applications. Springer. p. 24. ISBN 0-7923-6903-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=PJLlWzMBKjkC&printsec.

- Vallado, David Anthony (2001). Fundamentals of Astrodynamics and Applications. Springer. p. 28. ISBN 0-7923-6903-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=PJLlWzMBKjkC&printsec.

- Vallado, David Anthony (2001). Fundamentals of Astrodynamics and Applications. Springer. p. 30. ISBN 0-7923-6903-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=PJLlWzMBKjkC&printsec.