Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Asuncion Barbero | -- | 2382 | 2022-10-27 11:05:42 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | -4 word(s) | 2378 | 2022-10-28 02:58:36 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

González-Andrés, P.; Fernández-Peña, L.; Díez-Poza, C.; Barbero, A. The Tetrahydrofuran Motif in Marine Lipids and Terpenes. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/31591 (accessed on 07 March 2026).

González-Andrés P, Fernández-Peña L, Díez-Poza C, Barbero A. The Tetrahydrofuran Motif in Marine Lipids and Terpenes. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/31591. Accessed March 07, 2026.

González-Andrés, Paula, Laura Fernández-Peña, Carlos Díez-Poza, Asunción Barbero. "The Tetrahydrofuran Motif in Marine Lipids and Terpenes" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/31591 (accessed March 07, 2026).

González-Andrés, P., Fernández-Peña, L., Díez-Poza, C., & Barbero, A. (2022, October 27). The Tetrahydrofuran Motif in Marine Lipids and Terpenes. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/31591

González-Andrés, Paula, et al. "The Tetrahydrofuran Motif in Marine Lipids and Terpenes." Encyclopedia. Web. 27 October, 2022.

Copy Citation

Heterocycles are particularly common moieties within marine natural products. Specifically, tetrahydrofuranyl rings are present in a variety of compounds which present complex structures and interesting biological activities. Focusing on terpenoids, a high number of tetrahydrofuran-containing metabolites have been isolated. They show promising biological activities, making them potential leads for novel antibiotics, antikinetoplastid drugs, amoebicidal substances, or anticancer drugs. Thus, they have attracted the attention of the synthetics community and numerous approaches to their total syntheses have appeared.

oxygen heterocycles

tetrahydrofuran

total synthesis

biological activity

terpenes

1. Lipids

1.1. Lipid Alcohols

C19 Lipid Diols

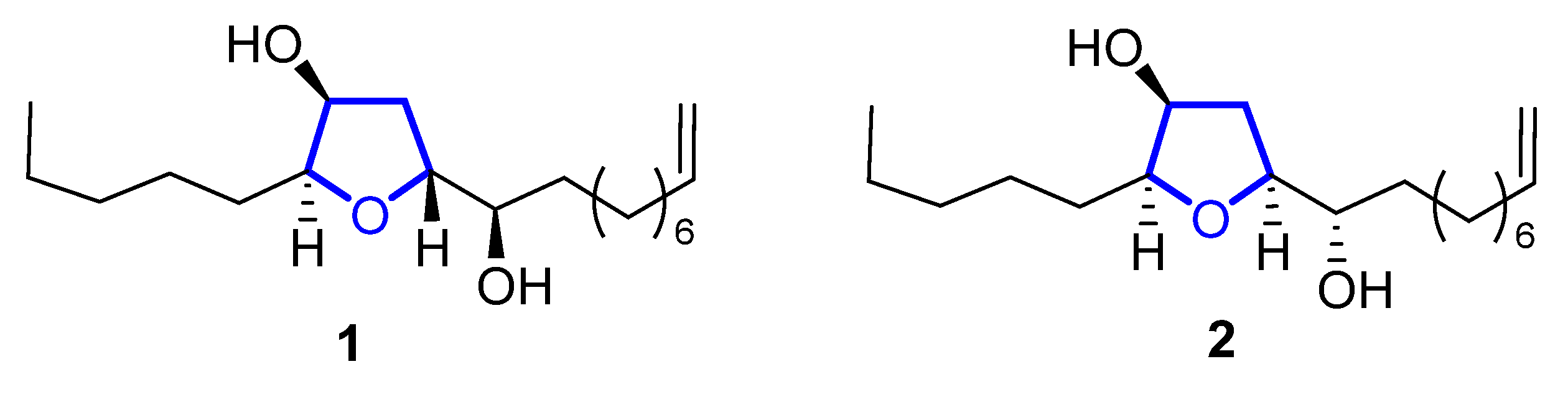

Diastereomeric trans-oxylipids 1, and cis-oxylipid 2 (Figure 1), were isolated in 1980 [1] and 1998 [2], respectively, from the brown alga Notheia anomala. Their structure and relative stereochemistry were assigned by 1D and 2D NMR spectral data and confirmed by single-crystal X-ray analysis. Their absolute configuration was determined by the Horeau method in the case of compound 1, and by the advanced Mosher method for compound 2. Both of them display in vitro antihelmintic activity, inhibiting larval development in parasitic nematodes. The trans-isomer 1 showed LD50 values against Haemonchus contortus (1.8 ppm) and Trichostrongylus colubriformis (9.9 ppm), comparable to those of the commercial nematocides levamisole and closantel. Synthetic routes for these oxylipids were recently reviewed [3].

Figure 1. Structure of trans-oxylipid 1 and cis-oxylipid 2.

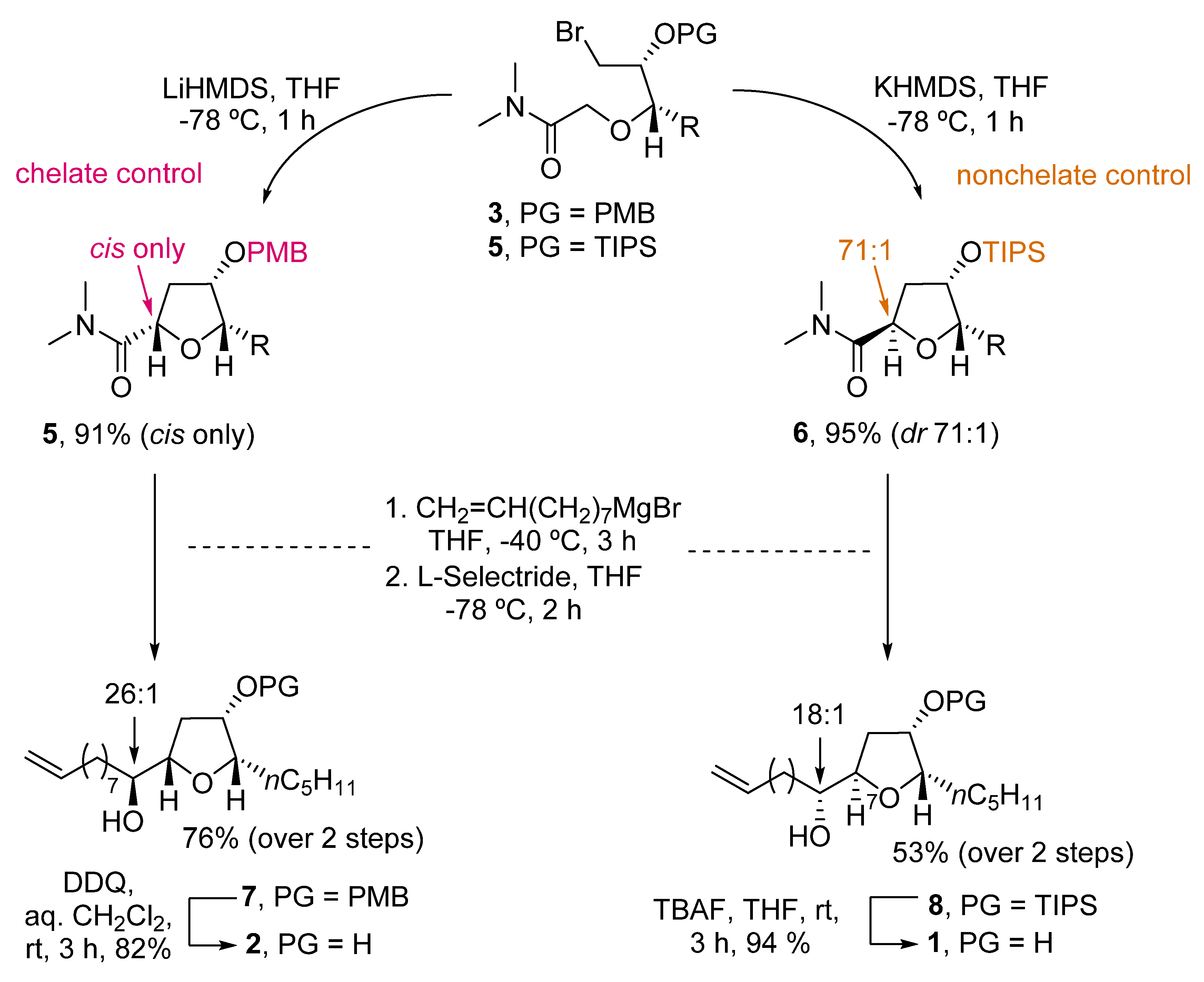

An elegant example of the stereodivergent synthesis of both isomers was developed by Kim et al. [4]. They developed an intramolecular amide enolate alkylation, where the C3-hydroxy protecting group selection permits the formation of the desired isomer (Scheme 1). Thus, starting from PMB-protected bromoamide 3, reaction with LiHMDS afforded only the cis-product 4. The preferent formation of the cis-isomer was due to the chelating ability of the PMB group. Therefore, when using a nonchelating group such as TIPS (compound 5), the reaction with KHMDS predominantly yielded the trans-THF 6. Further reaction of 4 and 6 with CH2=CH(CH2)7MgBr and reduction with L-selectride afforded 7 and 8 in good yields (76% and 53% over two steps, respectively). Deprotection of 7 with DDQ, and 8 with TBAF, respectively, gave cis-oxylipid 2 in 82% yield and the trans-isomer 1 in 94% yield.

Scheme 1. Stereodivergent synthesis of trans- and cis-oxylipids 1 and 2 by Kim.

1.2. Fatty Acids

1.2.1. Petromyroxols

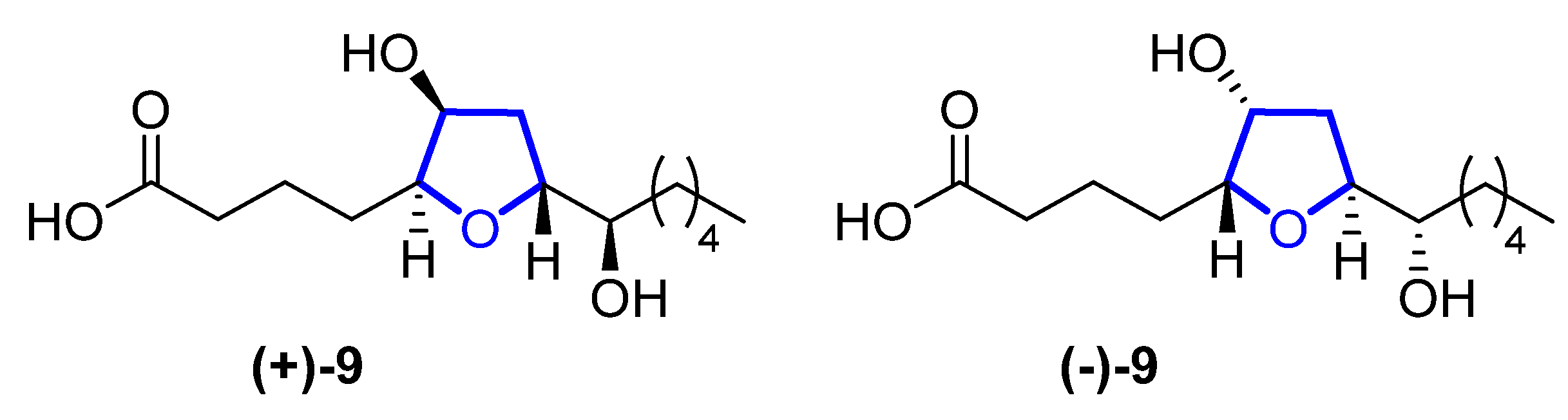

In 2015, Li reported the isolation of (+)- and (−)-petromyroxols (9) [5]. They are oxylipids isolated from water conditioned with larval sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus L. Interestingly, these molecules are the first tetrahydrofuran acetogenindiols isolated from a vertebrate animal (Figure 2). The absolute configuration of each enantiomer was determined by a combination of Mosher ester analysis and comparison with related natural and synthetic products. The (+)-9 shows a potent olfactory response of 0.01 to 1 μM in the sea lamprey, while the (−)-isomer has a softer effect. Synthetic routes towards them were recently reviewed [3].

Figure 4. Structures of (+)-and (-)-petromyroxol 9.

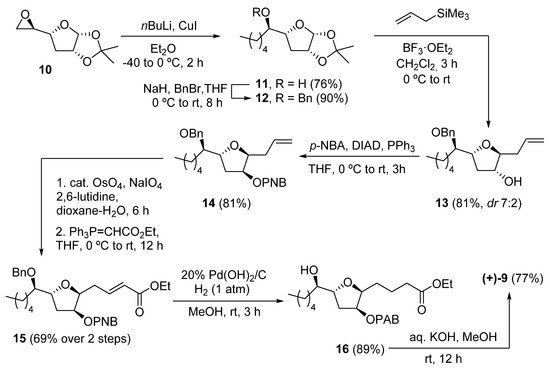

A recent example of the synthesis of (+)-9, along with all possible diastereoisomers, was presented in 2020 by Ramana and coworkers [6]. The synthetic route started from the commercial THF compound 10 (Scheme 2). The alkyl chain was installed by reaction with the appropriate cuprate. Subsequent benzyl protection of 11 afforded 12, which after reaction with allyltrimethylsilane, yielded the desired diastereomer (7:2 ratio) of the allylated THF 13. After protection with a para-nitrobenzoate (PNB) group under Mitsunobu conditions, compound 14 was subjected to oxidative olefin cleavage with OsO4/NaIO4 and subsequent Wittig olefination to obtain a-b-unsaturated ester 15. Hydrogenation with Pearlman catalyst (20% Pd(OH)2/C) afforded 16 in 89% yield, where the benzyl group, the double bond, and the nitro group were all reduced. Finally, hydrolysis of both ester groups with KOH in methanol afforded the desired (+)-petromyroxol in 77% yield.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of (+)-petromyroxol by Ramana and coworkers.

1.2.2. PMA

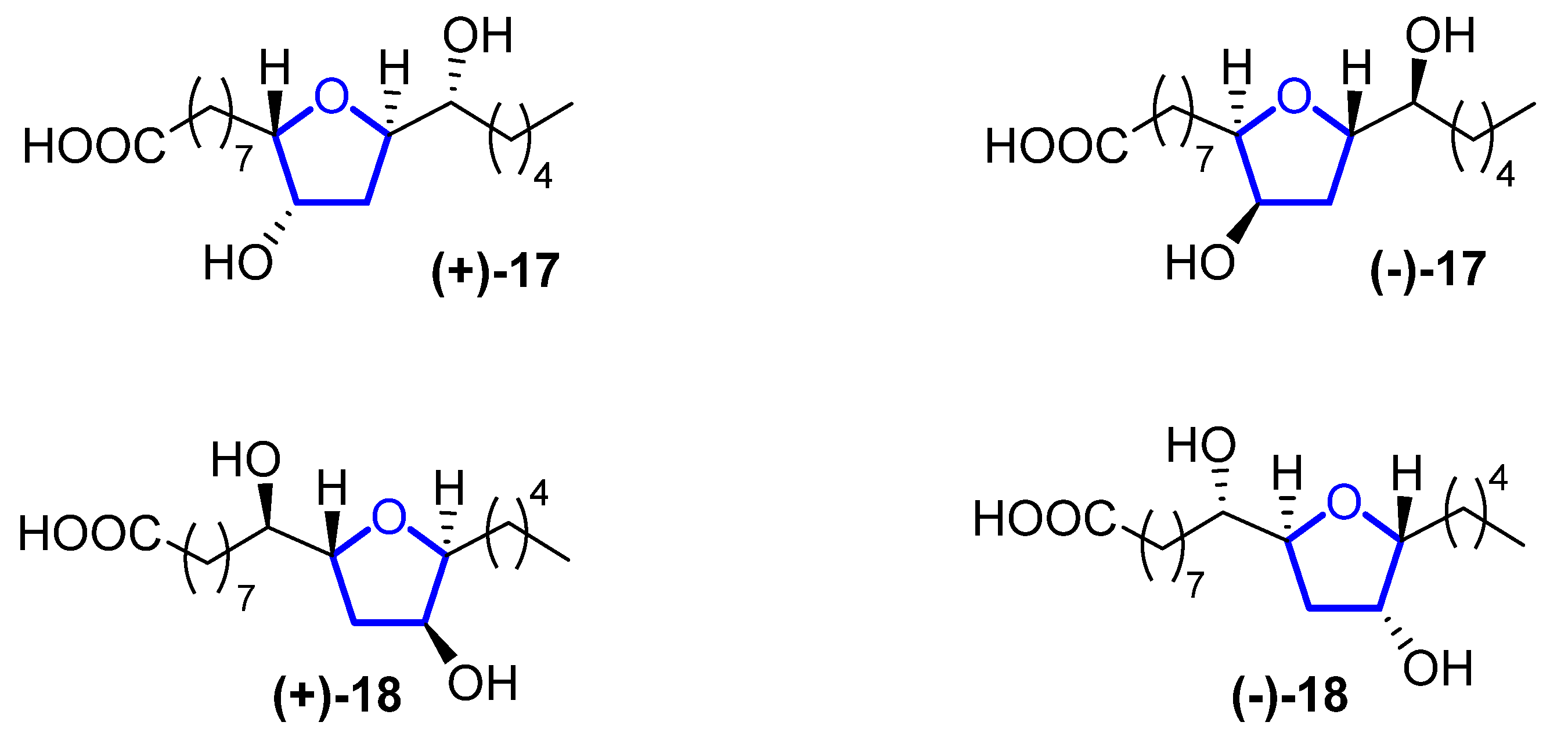

Petromyric acids A and B (PMA and PMB) are dehydroxylated tetrahydrofuranyl fatty acids that were isolated from larval washing extracts from the sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus in 2018 [7]. From the washing extract, four fatty acids related to the acetogenin family were identified: (+)-PMA ((+)-17), (−)-PMA ((−)-17), (+)-PMB ((+)-18), and (−)-PMB ((−)-18) (Figure 5). Their chemical structure was elucidated by NMR spectroscopy and confirmed by chemical synthesis and X-ray crystallography.

Figure 3. Structure of (+)-PMA ((+)-17), (−)-PMA ((−)-17), (+)-PMB ((+)-18), and (−)-PMB ((−)-18).

Sea lampreys are anadromous fishes that migrate, using their olfactory cues to orientate, from the ocean to freshwater to find a suitable spawning stream. When approaching river mouths, the decision of which stream is optimal to spawn in is taken using their olfactory system to detect a pheromone emitted from larval sea lampreys. When investigating larval washing extracts, four fatty acids were identified, but only (+)-17 has proven to be the pheromone that guides lamprey adults. However, its enantiomer, (−)-17, does not produce the same behavioral effect. Fatty acid analogues have been reported to be pheromones in insects, but this is the first identification in fish. The sea lamprey is a destructive invader in the Laurentian Great Lakes, while in Europe, its population has decreased precipitously, so (+)-17 can be used for the control and conservation of their populations.

Although they have a high potential for application, to the best of our knowledge, no total synthesis has been reported so far for these compounds.

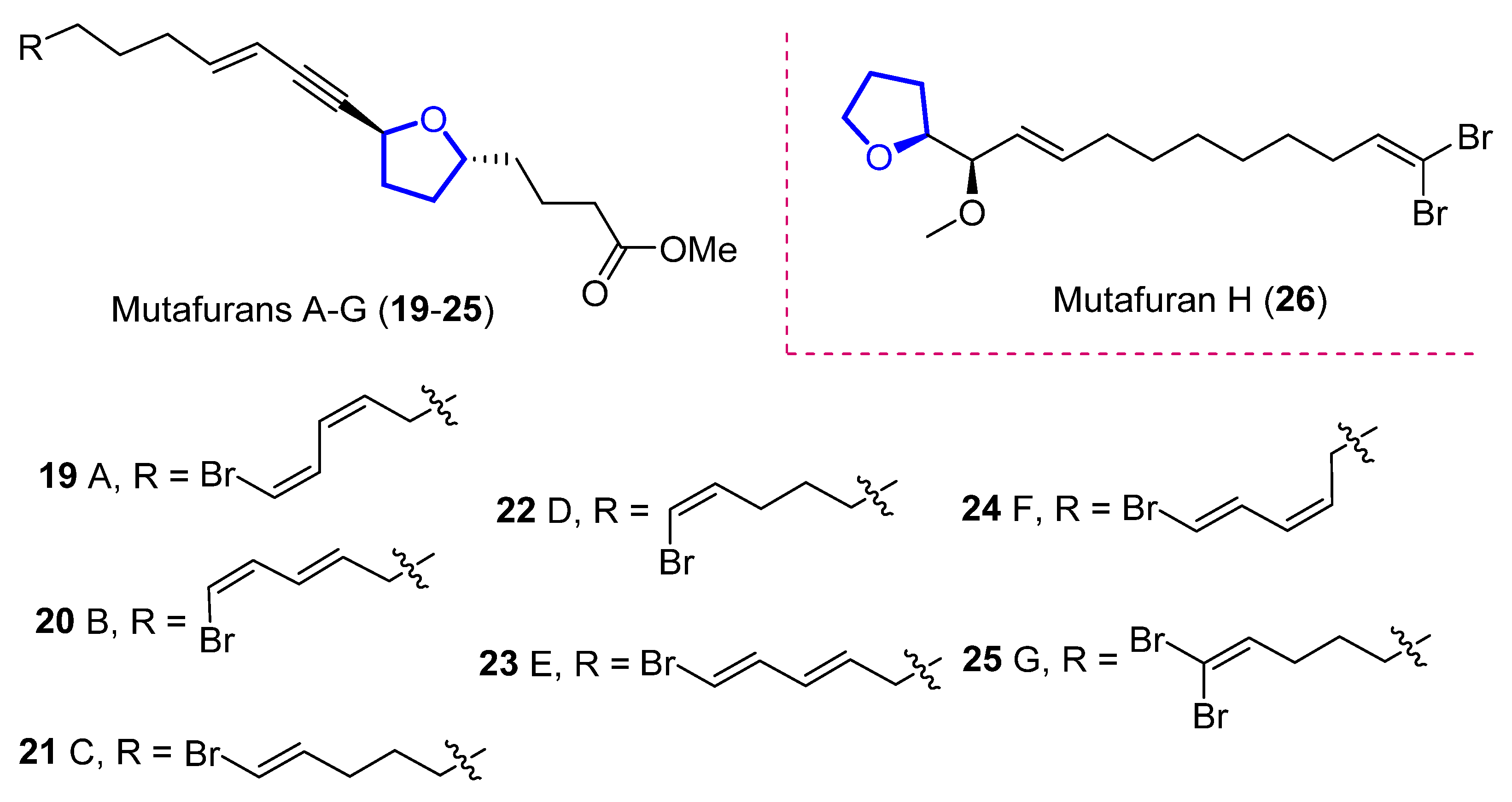

1.2.3. Mutafurans

Mutafurans A–G (19–25) are brominated ene-ynetetrahydrofurans (Figure 4) that were isolated by Molinski in 2007 from the marine sponge Xextospongia muta [8]. Later, Liu reported the isolation of mutafuran H (26), a brominated ene-tetrahydrofuran isolated from sponge Xextospongia testudinaria within other sterols and brominated compounds [9]. Their structure and absolute configuration were determined by 1D and 2D magnetic resonance, mass spectrometry, and circular dichroism.

Figure 4. Structure of mutafurans A–G and the yne-lacking mutafuran H.

Mutafurans A–D showed moderate antifungal activity against the fungus Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii, but were inactive against Candida albicans (ATCC14503 and 96–489) and Candida glabrata [8]. Furthermore, mutafuran H showed biological activity against Artemia salina larvae (LC50 = 2.6 μM) and a significant acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity (IC50 = 0.64 μM) [9]. No synthetic approach has been reported to date.

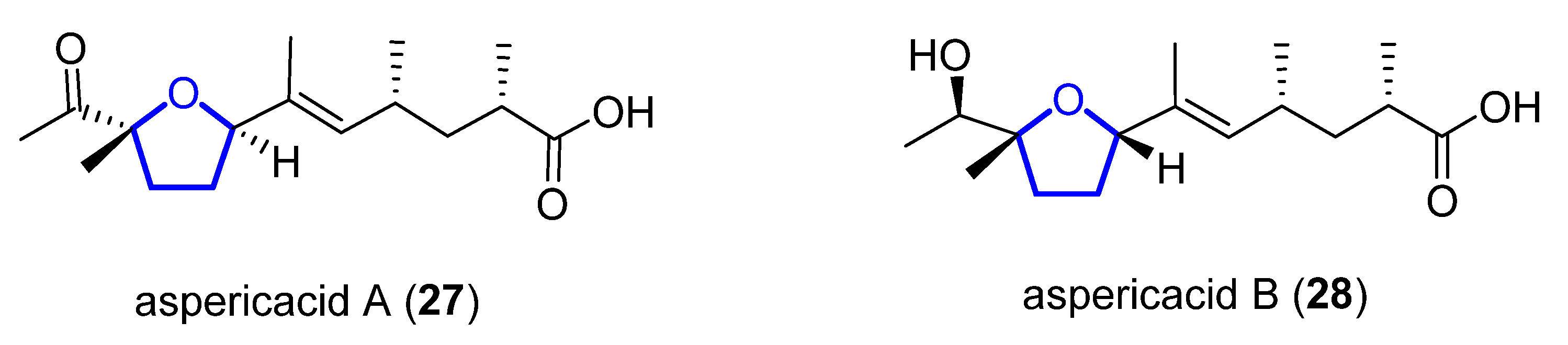

1.2.4. Aspericacids

Aspericacids A (27) and B (28) were isolated in 2020 by Ding and He from the sponge-associated Aspergillus sp. LS78 [10]. Both compounds bear a 2,5-disubstituted tetrahydrofuran ring coupled with an unsaturated fatty acid (Figure 5). Their structure was determined by HRESIMS and 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy, while their absolute configuration was established relying on electronic circular dichroism (ECD). Compound 27 presents a moderate inhibitory activity against Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans with a MIC value of 50 μg/mL, although 28 has a weaker activity, MIC = 128 μg/mL. No synthetic approach has been reported to date.

Figure 5. Structure of aspericacids A 27 and B 28.

2. Terpenes

2.1. Monoterpenes

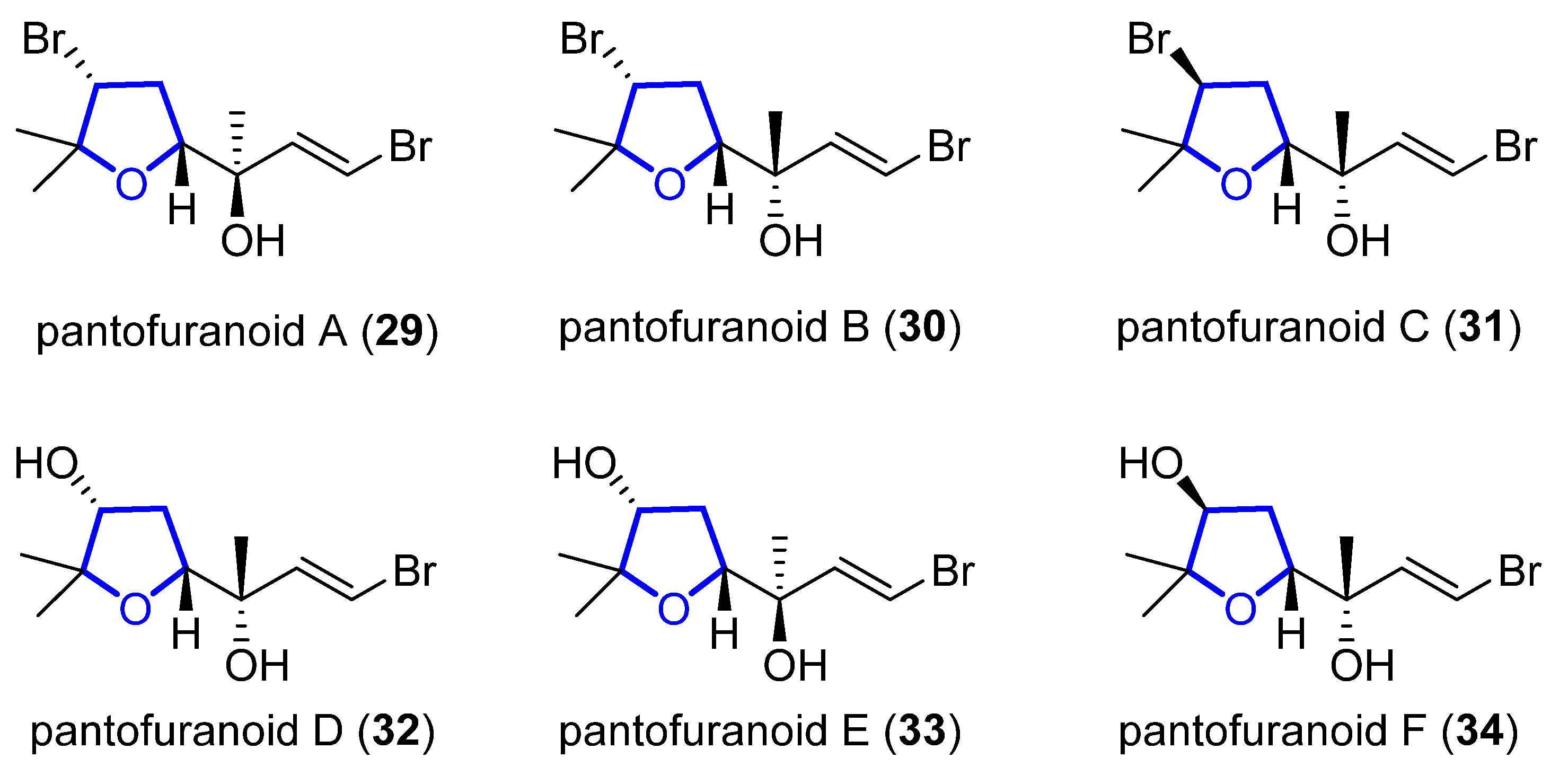

2.1.1. Pantofuranoids

Pantofuranoids A–F (29–34) are monoterpenes that were isolated in 1996 from the Antarctic red alga Pantoneura plocamioides [11]. They are the first monoterpenes found to contain a tetrahydrofuran moiety, and their common framework (Figure 6) suggests that they all come from the same terpene precursor.

Figure 6. Proposed structure of pantofuranoids.

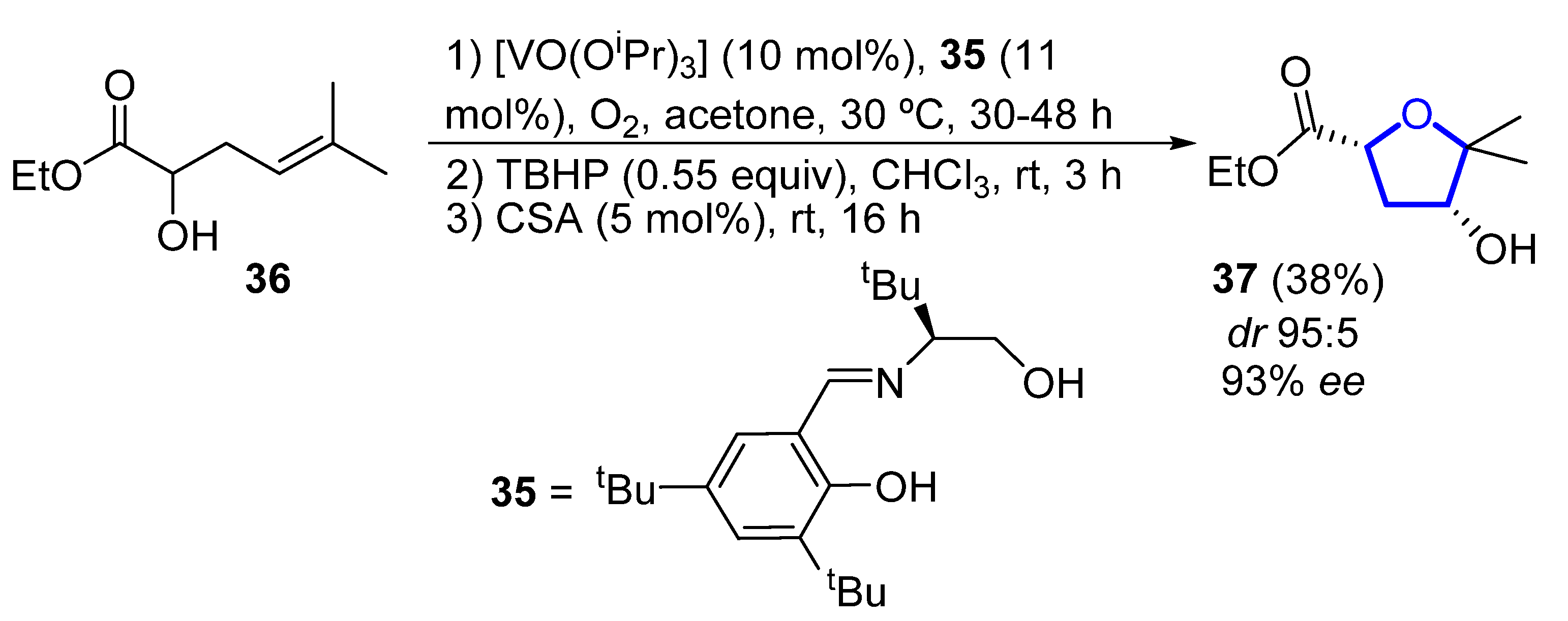

In 2006, Toste reported the enantioselective total synthesis of (−)-33, in which the key step is a vanadium-catalyzed sequential resolution/oxidative cyclization [12]. Using an in situ generated vanadium(V)–oxo complex with chiral tridentate Schiff base ligand 35 as catalyst, racemic homoallylic alcohol 36 was readily converted into 2,4-cis-substituted THF 37 (Scheme 3). The observed stereochemistry can be explained through a chair-like transition state in which coordination of the pseudo-equatorial ester group to the vanadium complex determines the selectivity of the syn-epoxidation step. Then, compound 37 was further elaborated to (−)-33 in 6 steps and 29% overall yield from 37.

Scheme 3. Vanadium-catalyzed synthesis of the tetrahydrofuranyl core of (−)-pantofuranoid E by Toste.

2.1.2. Furoplocamioids

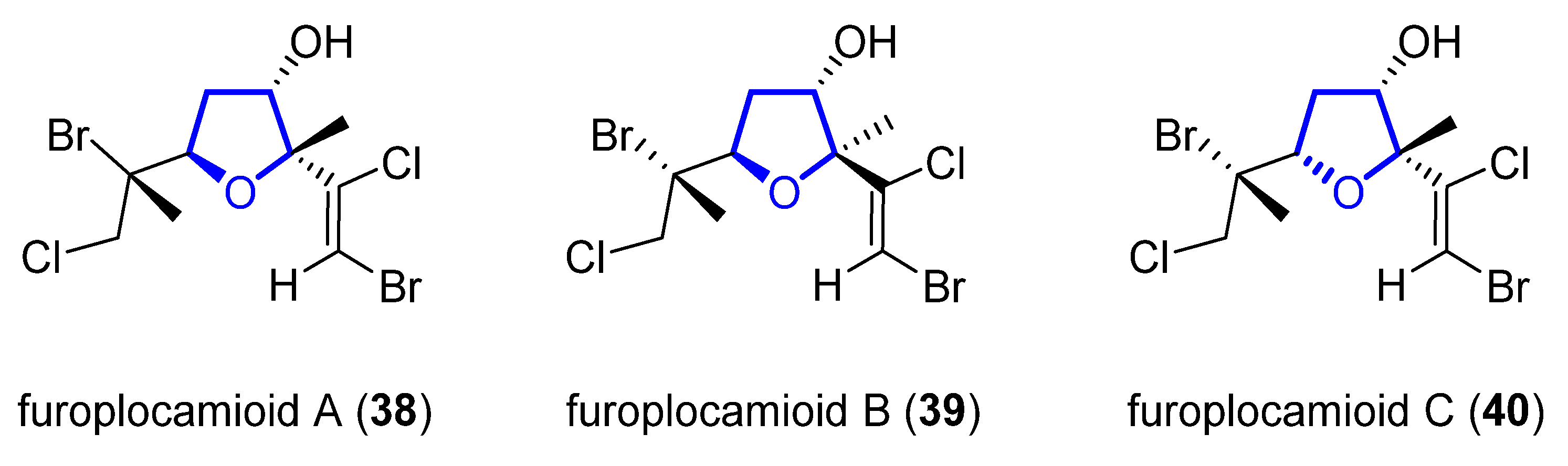

Furoplocamioids A–C 38–40 (Figure 7) are monoterpenes that were isolated in 2001 from the red marine alga Plocamium cartilagineum [13]. They bear an unusual polyhalogenated tetrahydrofuranyl ring. Their structural similarity to pantofuranoids suggests a close relationship between the species that produce them. This is an interesting fact, since Plocamium cartilagineum and Pantoneura plocamioides are classified in different orders, Gigartinales and Ceramiales. Therefore, a taxonomic revision could be required. Later, the Darias group determined the C7 relative stereochemistry by comparison with the NMR spectra of similar reported terpenes [14]. González-Coloma and coworkers found that 38 and 40 show antifeedant effects against Leptinotarsa decemlineata. It was shown that 40 was also an efficient aphid repellent (against Mizuspersicae and Ropalosiphumpadi) and selective insect cell toxicant. In addition, both compounds showed low mammalian toxicity and phytotoxic effects [15].

Figure 7. Structure of furoplocamioids A–C (38–40).

2.2. Sesquiterpenes

2.2.1. Heronapyrrols

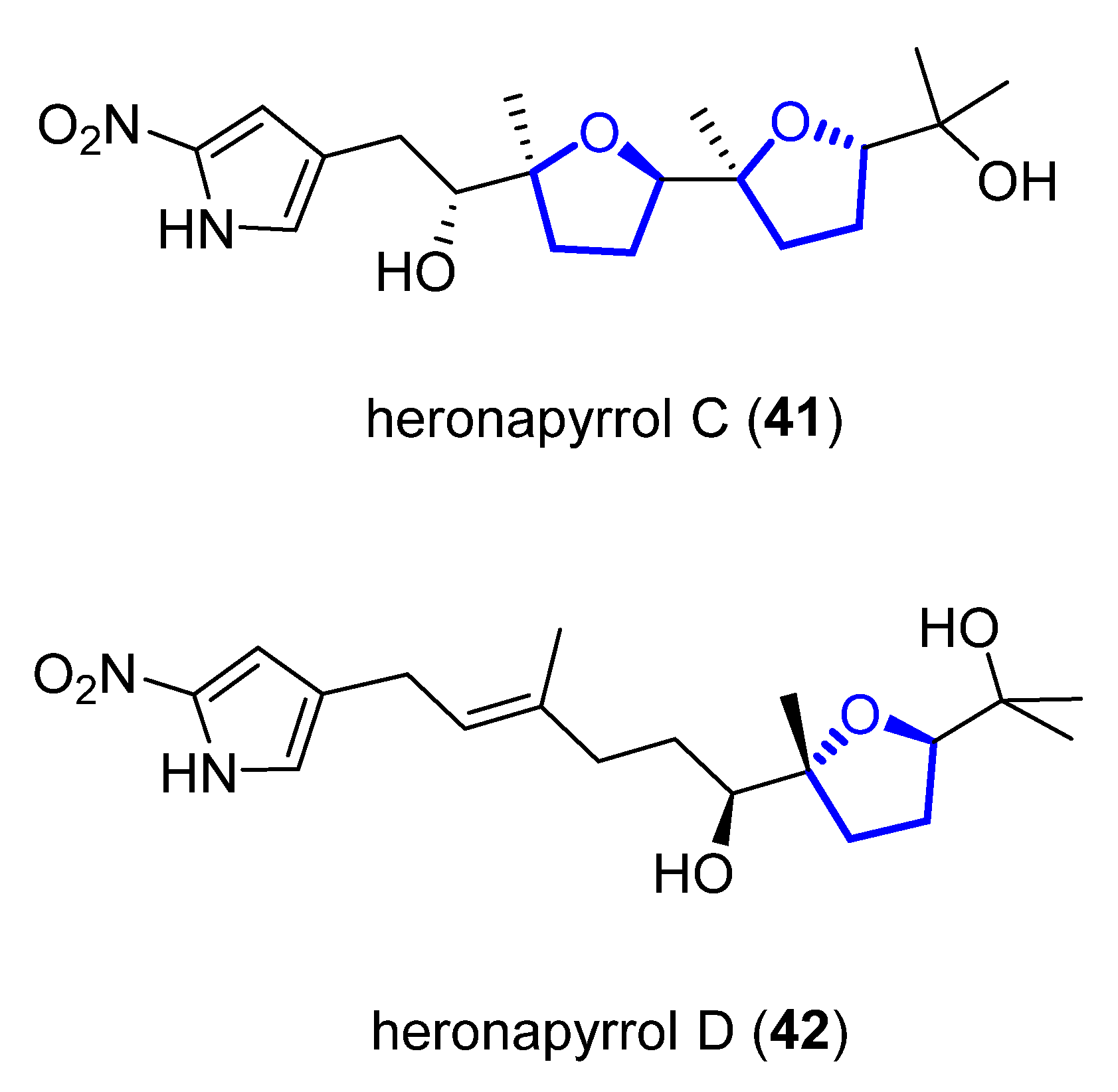

Heronapyrrols A–C are pyrroloterpenes that were isolated in 2010 from a marine Streptomyces sp. CMB-M0423 [16]. They present bioactivity against Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 9144 and Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 but no mammalian cytotoxicity. Heronapyrrol C (41), apart from the characteristic and unusual 2-nitropyrrol moiety of this family, presents a bis-tetrahydrofuran core. Later, Capon and Stark first synthesized and then isolated heronapyrrol D (42) (Figure 8) from the same marine-derived microbe [17]. Heronapyrrol D displays bioactivity against Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 (IC50 = 1.8 μM), Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 12228 (IC50 = 0.9 μM), and Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 (IC50 = 1.8 μM). However, it is inactive against the Gram-negative bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 10145 and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922.

Figure 8. Structure of (+)-heronapyrrol C (41) and (+)-heronapyrrol D (42).

To determine the relative and absolute stereochemistry of (+)-41, Stark and coworkers proposed and synthesized the most likely stereostructure of its enantiomer (−)-41, based on a biomimetic polyepoxide cyclization [18]. The same authors also reported the preparation of a bioisosteric carboxylate analog of (−)-41 [19].

The first total synthesis of (+)-41 was reported in 2014 by Brimble and coworkers, who used as key steps to introduce the five stereogenic centers a Julia–Kocienski coupling, a Shi epoxidation, and a catalytic epoxide-opening reaction [20]. The same year, the first total synthesis of (+)-42 was achieved by Capon and Stark using a similar approach [17]. In 2016, Brimble and Furkert reviewed the isolation and synthesis of this family of compounds [21].

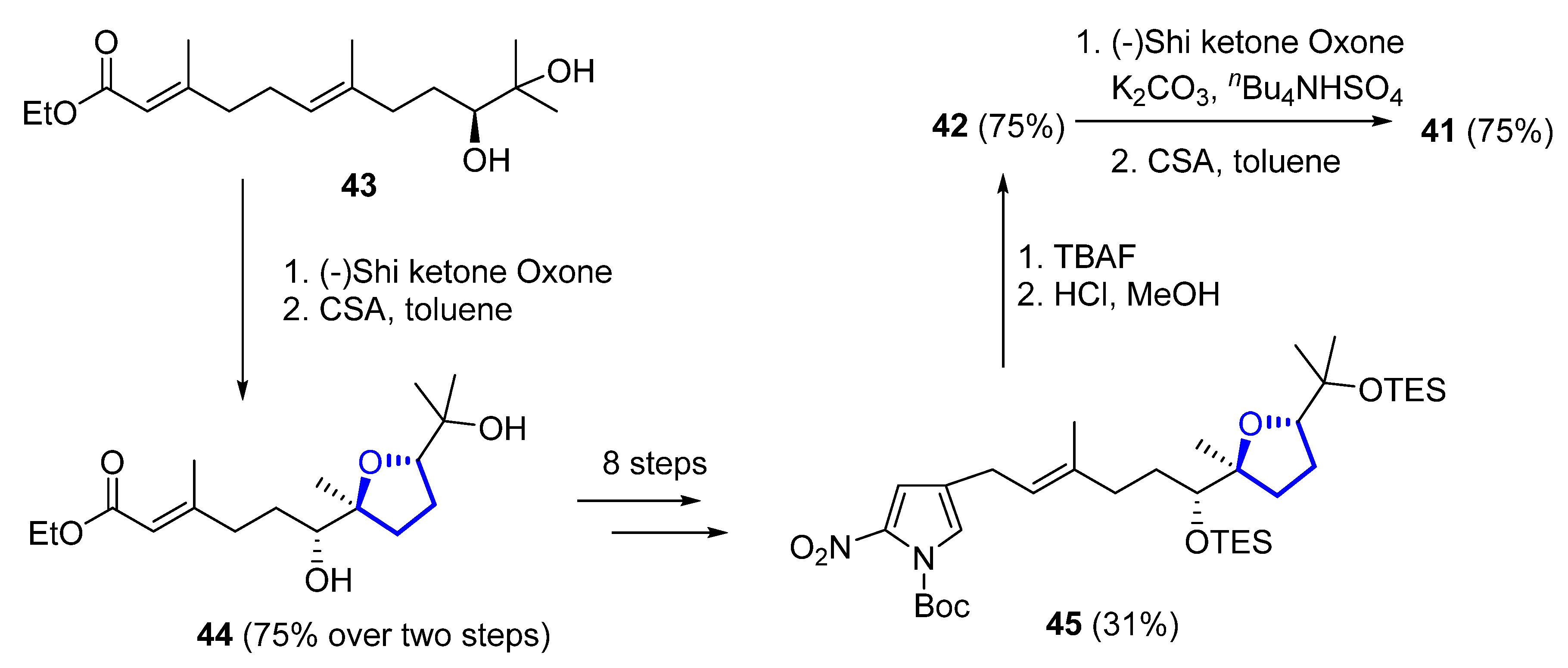

Later on, the same authors reported another total synthesis for both (+)-41 and (+)-42 [22]. Shi epoxidation of diol 43, followed by CSA-catalyzed epoxide opening and cyclization, produces diastereomerically pure 44 in 75% yield over two steps. A further eight steps, with 31% yield over them, produces intermediate 45, which deprotection gives (+)-heronapyrrol D (42). Epoxidation of 42 with a Shi ketone catalyst, followed by CSA-catalyzed epoxide opening, produced enantiomerically pure (+)-heronapyrrol C (41) in 75% yield (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Synthesis of (+)-heronapyrrol C (41) and (+)-heronapyrrol D (42).

Other synthetic approaches towards the 2-nitropyrrole system have been investigated by Brimble and Furkert, finding that Sonogashira coupling of 4-iodo-2-nitropyrrole with the appropriate alkyne was more effective than an approach relying on Stille coupling [23].

2.2.2. Kumausallene and Kumausyne

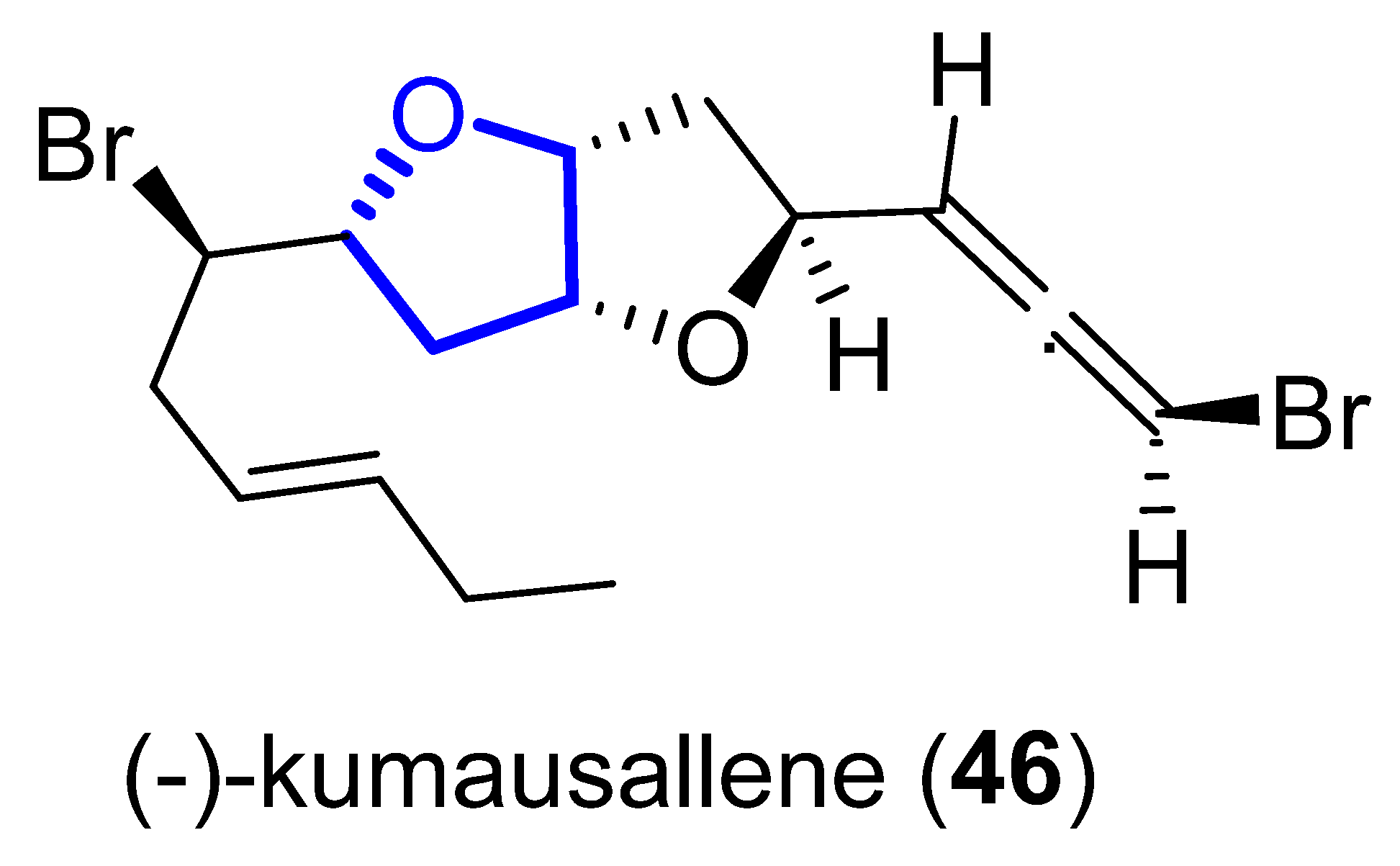

(−)-Kumausallene (46) was isolated in 1983 from the marine red alga Laurencia nipponica Yamada [24]. This compound belongs to a family of non-isoprenoid sesquiterpenes that contain a 2,6-dioxa-bicyclo [3.3.0]octane core with an exo-cyclic bromoallene (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Structure of kumausallene.

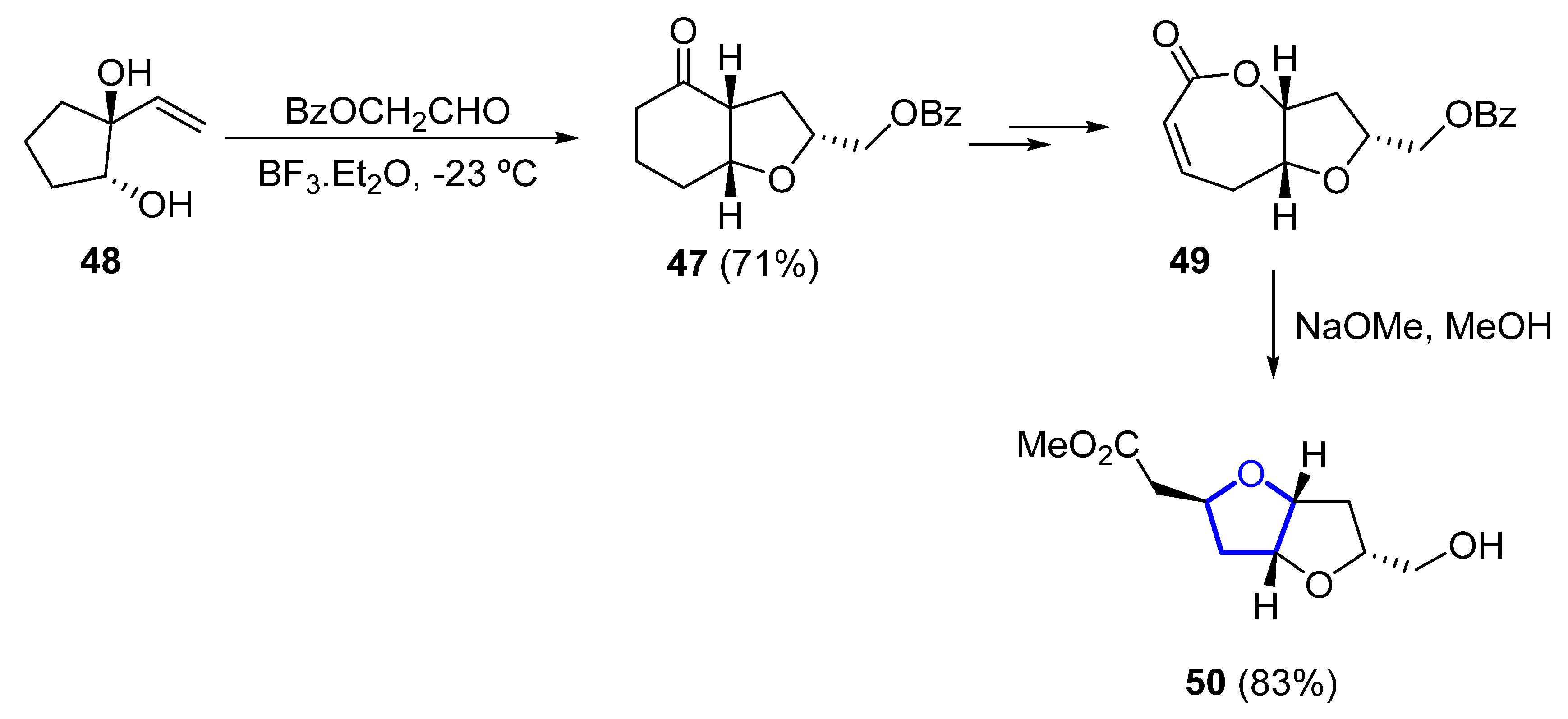

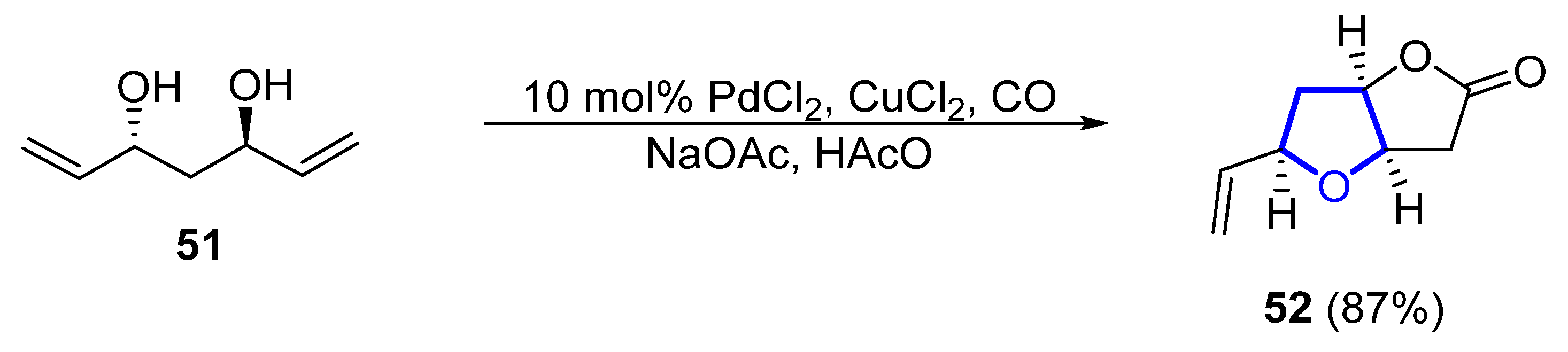

In 1993, the first total synthesis of (±)-46 was reported by Overman, who chose a hexahydrobenzofuranone 47 (obtained by a Prins cyclization–pinacol rearrangement from 48) as the key intermediate for the construction of the bis-tetrahydrofuran unit (Scheme 5). Further transformation of 47 into bicyclic lactone 49 (within three further steps) and final methanolisis and tandem cyclization of the corresponding hydroxyester provided, in good yield, the desired dioxabicyclo [3.3.0]octane 50 [25].

Scheme 5. Synthesis of the dioxabicyclo [3.3.0]octane unit of (±)-kumausallene (46) by Overman.

In 2011, a synthetic approach for (−)-46 by Tang employed a desymmetrization strategy for the formation of the 2,5-cis-substituted THF ring [26]. C2-symmetric diol 51 is desymmetrized by a palladium-catalyzed cascade reaction to form lactone 52 in 87% yield (Scheme 6). The total synthesis comprised just 12 steps from commercial acetylacetone. In 2015, Ramana et al. published a different formal total synthesis of (−)-46 based on a chiral pool approach [27].

Scheme 6. Synthesis of the tetrahydrofuranyl ring of (−)-46 through desymmetrization by Tang.

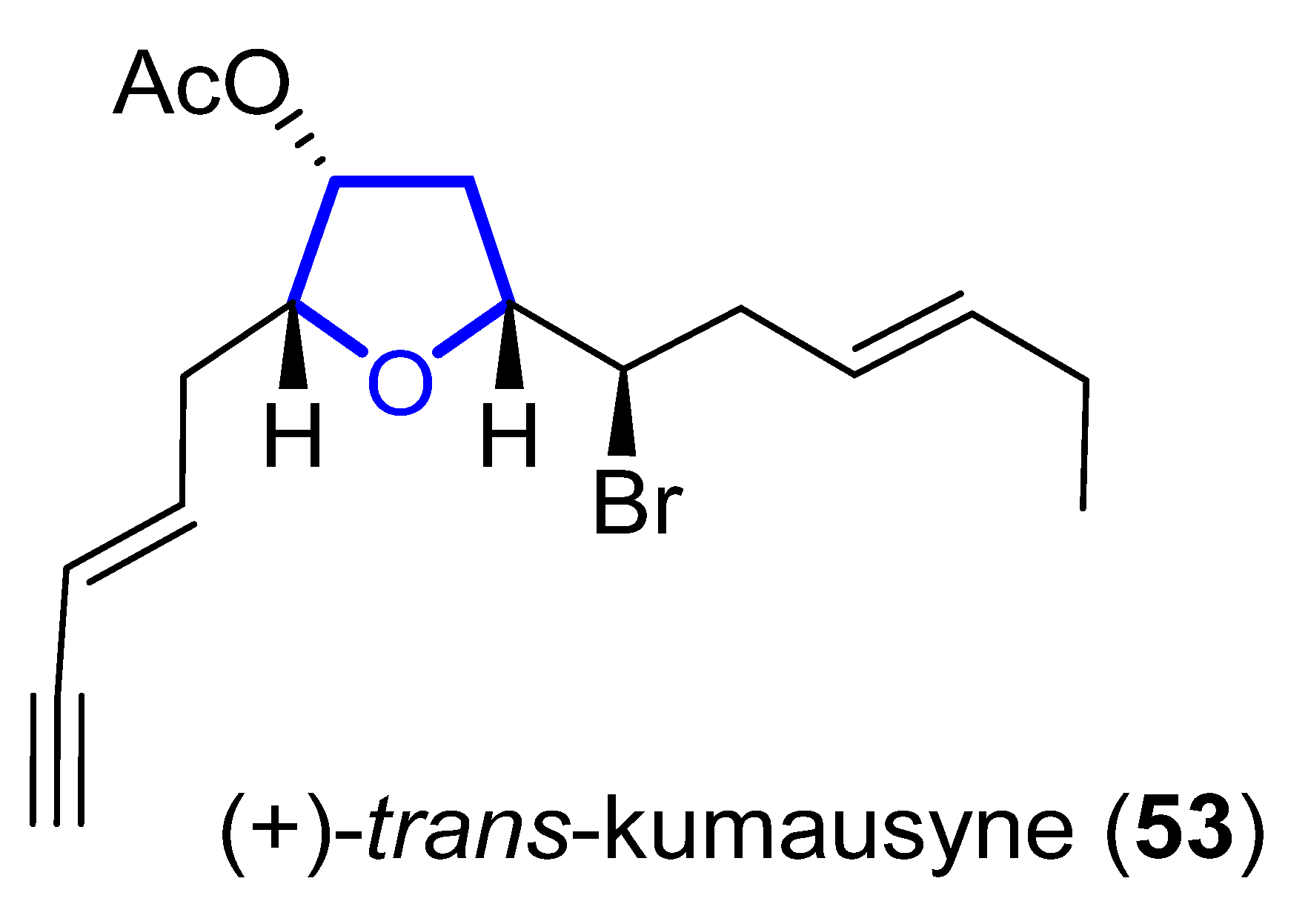

(+)-Trans-Kumausyne (53) (Figure 12) is a halogenated non-isoprenoid sesquiterpene isolated in 1983 from red alga Laurencia nipponica Yamada [28]. Its first total synthesis was achieved in 1991 by Overman and coworkers [29]. A review covering the synthetic approaches towards kumausallene and kumausyne, and other natural products containing a 2,3,5-trisubstituted tetrahydrofuran moiety, was published by Fernandes in 2020 [3].

Figure 12. Structure of (+)-trans-Kumausyne (53).

2.3. Diterpenes

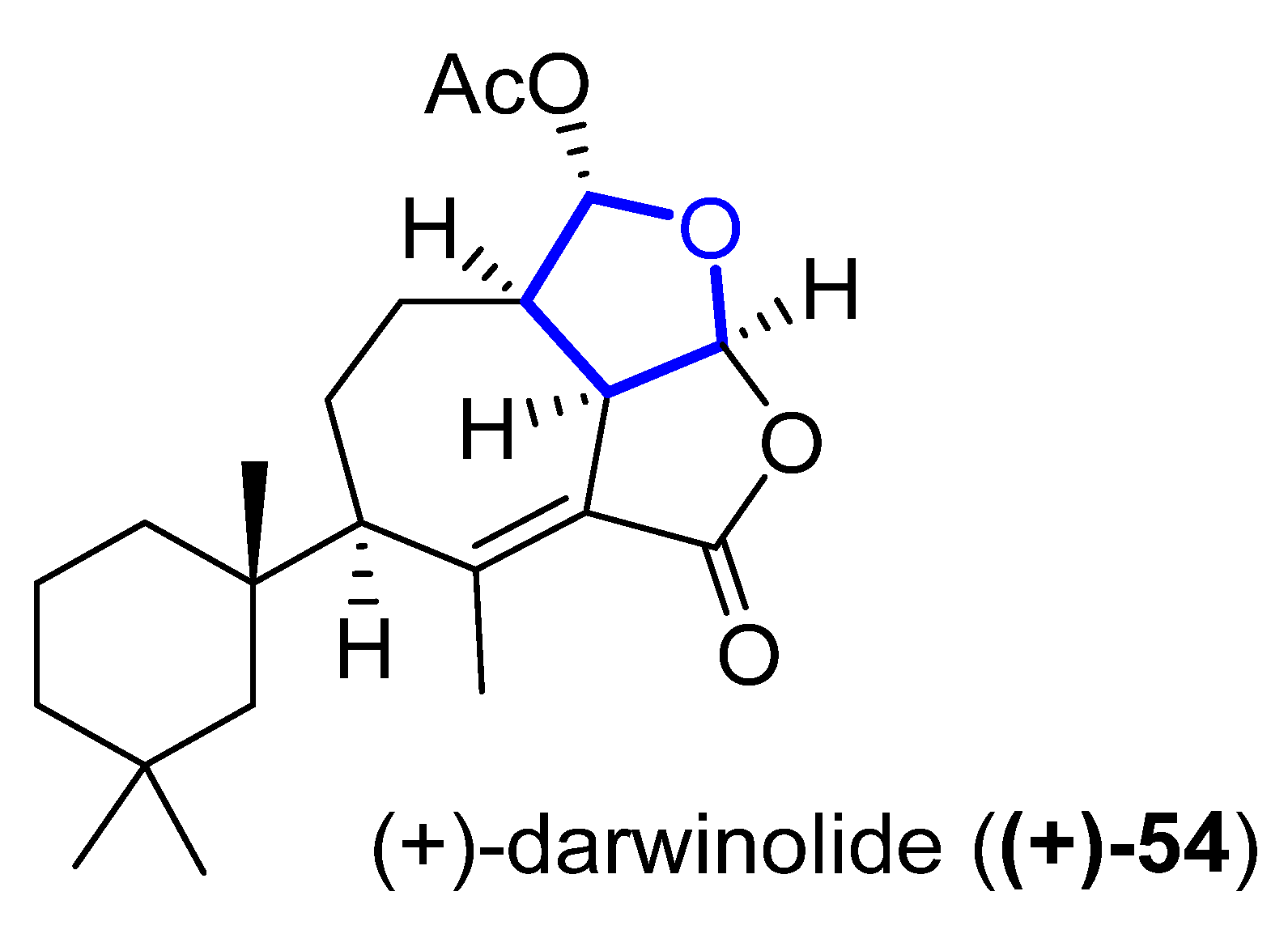

2.3.1. Darwinolide

(+)-Darwinolide (54) (Figure 13) is a diterpene isolated in 2016 by Baker from the Antarctic Dendroceratid sponge Dendrilla membranosa [30]. It presents fourfold selectivity against a biofilm phase of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (IC50 of 33.2μM), compared to the planktonic phase (with the higher MIC of 132.9 μM). This interesting property and its low mammalian cytotoxicity (IC50 of 73.4 mM) against a J774 macrophage cell line turn darwinolide into a possible scaffold for antibiofilm-specific antibiotics. Additionally, it was found to have modest activity (11.2 μM) against L. donovani-infected macrophages [31].

Figure 13. Structure of (+)-darwinolide ((+)-54).

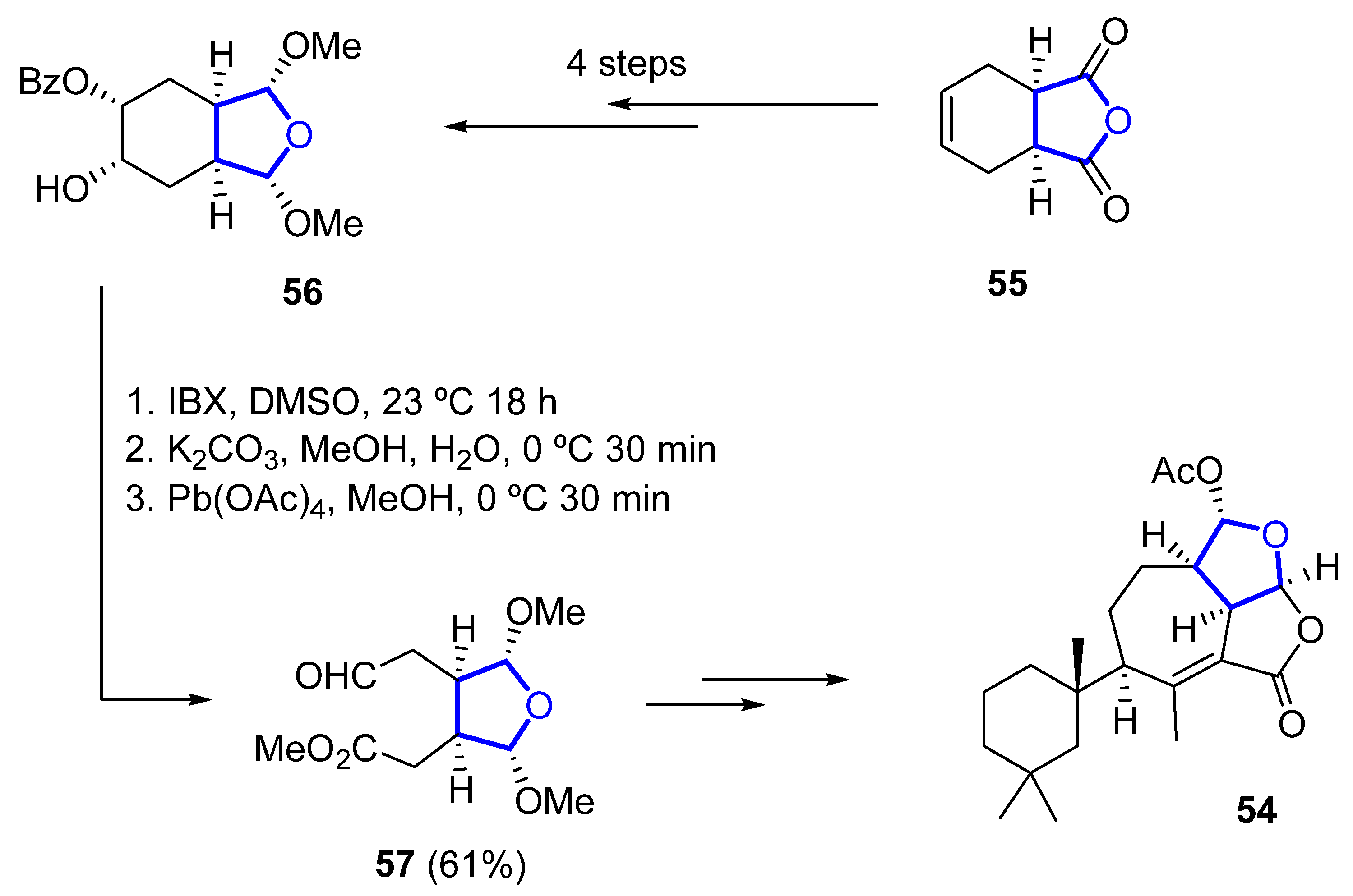

Its total synthesis was reported in 2019 by Christmann [32]. The required tetrahydrofuranyl ring is installed starting from the commercially available anhydride 55, which is converted to the 2,5-dimethoxylated tetrahydrofuran 56 in four steps. A sequence of oxidation (with o-iodoxybenzoic acid), saponification, and Criegee oxidation with Pb(OAc)4 is then used to convert 56 into 57 in 61% yield over three steps (Scheme 7). A further 14 linear steps are needed to complete the total synthesis of 54, with an overall yield of 1.4%.

Scheme 7. Synthesis of the key THF-containing intermediate in Christmann’s total synthesis of darwinolide.

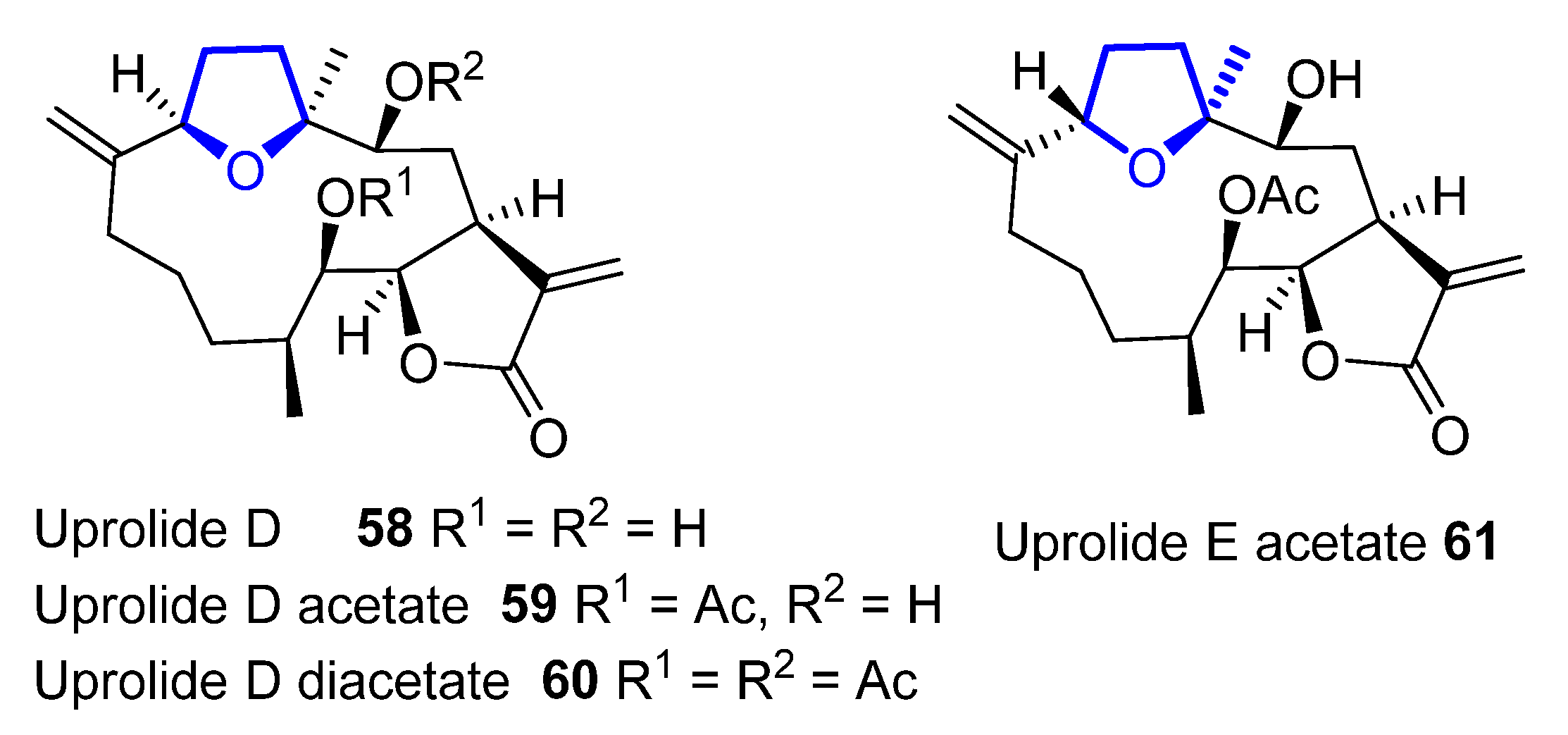

2.3.2. Uprolides

Cembranolides are a family of compounds related to cembrene, which is a 14-membered macrocyclic diterpene with multiple (E)-double bonds. Among them, uprolides are a subfamily of compounds named after the University of Puerto Rico. Uprolides A–G were isolated in 1995 by Rodríguez and coworkers from the Caribbean gorgonian Eunicea Mammosa and their structure was assigned by spectroscopic methods and chemical interconversion [33][34]. They are the first natural cembranolides from a Caribbean gorgonian that bear a double bond at C6 or C8. While uprolides A–C show an epoxy moiety, uprolides D–G seemed to contain a tetrahydrofuran moiety instead. Uprolides D (58), D acetate (59), D diacetate (60), and E acetate (61) (Figure 14) present a moderate cytotoxicity against HeLa cells ((IC50 = 2.5 to 5.1 µg/ ml). Moreover, 59 shows cytotoxicity against the following human tumor cell lines: CCRF-CEM T-cell leukemia (IC50 = 7.0 μg/mL), HCT-116 colon cancer (IC50 = 7.0 μg/mL), and MCF-7 breast adenocarcinoma (IC50 = 0.6 μg/mL).

Figure 14. Structure of tetrahydrofuran-containing members of the uprolide family.

Later structural revisions determined the presence of a tetrahydropyran ring, instead of the previously proposed tetrahydrofuran, in uprolides F diacetate and G acetate, hypotheses that were confirmed by asymmetric total synthesis of these natural products [35][36][37][38].

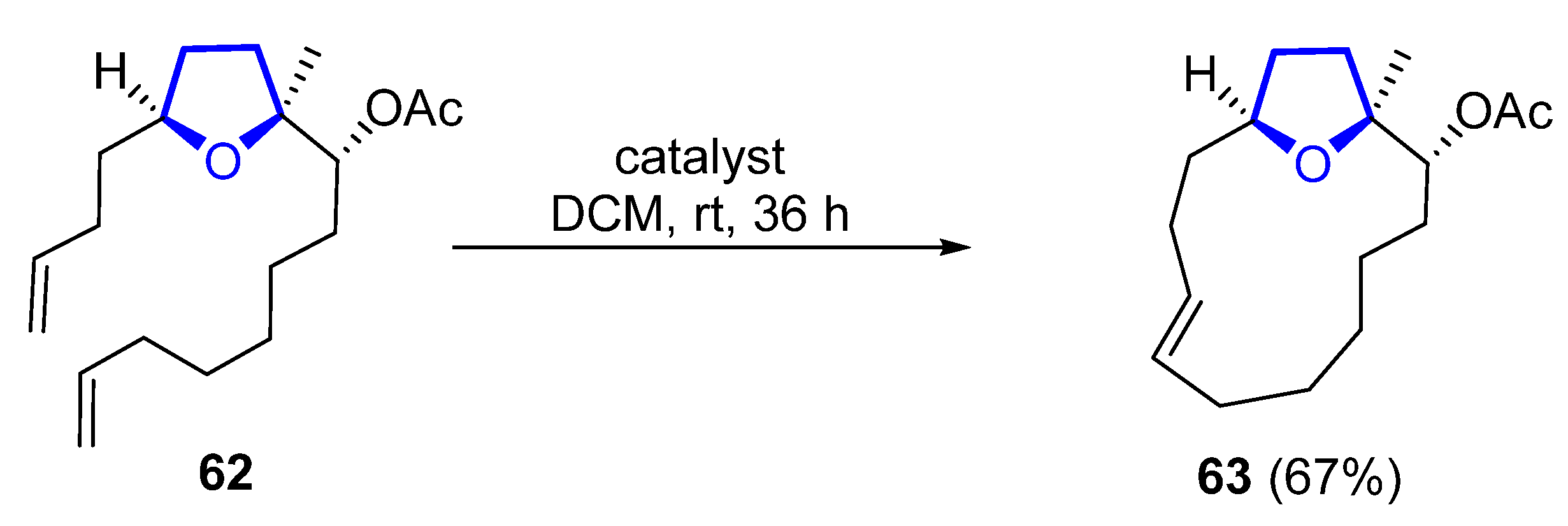

In 2007, a synthetic approach to obtain the macrocyclic core of 58 was proposed by Ramana [39]. The formation of the macrocyclic core is produced by ring-closing metathesis (RCAM) using a Grubbs’ first-generation catalyst. The RCAM of acetate 62 produces 13-membered macrocyclic 63 in 67% yield (Scheme 8). The macrocyclic core of uprolide E could not be synthesized using the same methodology.

Scheme 8. Synthesis of macrocyclic core of uprolide D by Ramana.

Marshall developed a synthetic route for C1/C14 bis-epimer of 58 in which the macrocyclization is produced by an intramolecuar Barbier reaction [40]. Some years later, other members of the uprolide family, which lack the tetrahydrofuran ring, have been isolated from the gorgonian octocoral Eunicea succinea [41].

References

- Warren, R.G.; Wells, R.J.; Blount, J.F. A novel lipid from the brown alga Notheia anomala. Aust. J. Chem. 1980, 33, 891–898.

- Capon, R.J.; Barrow, R.A.; Rochfort, S.; Jobling, M.; Skene, C.; Lacey, E.; Gill, J.H.; Friedel, T.; Wadsworth, D. Marine nematocides: Tetrahydrofurans from a southern Australian brown alga, Notheia anomala. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 2227–2242.

- Fernandes, R.A.; Pathare, R.S.; Gorve, D.A. Advances in Total Synthesis of Some 2,3,5-Trisubstituted Tetrahydrofuran Natural Products. Chem. Asian J. 2020, 15, 2815–2837.

- Jang, H.; Shin, I.; Lee, D.; Kim, H.; Kim, D. Stereoselective Substrate-Controlled Asymmetric Syntheses of both 2,5-cis- and 2,5-trans-Tetrahydrofuranoid Oxylipids: Stereodivergent Intramolecular Amide Enolate Alkylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6497–6501.

- Li, K.; Huertas, M.; Brant, C.; Chung-Davidson, Y.-W.; Bussy, U.; Hoye, T.R.; Li, W. (+)- and (−)-Petromyroxols: Antipodal Tetrahydrofurandiols from Larval Sea Lamprey (Petromyzon marinus L.) That Elicit Enantioselective Olfactory Responses. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 286–289.

- Mullapudi, V.; Ahmad, I.; Senapati, S.; Ramana, C.V. Total Synthesis of (+)-Petromyroxol, (−)-iso-Petromyroxol, and Possible Diastereomers. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 25334–25348.

- Li, K.; Brant, C.O.; Huertas, M.; Hessler, E.J.; Mezei, G.; Scott, A.M.; Hoye, T.R.; Li, W. Fatty-acid derivative acts as a sea lamprey migratory pheromone. PNAS 2018, 115, 8603.

- Morinaka, B.I.; Skepper, C.K.; Molinski, T.F. Ene-yne Tetrahydrofurans from the Sponge Xestospongia muta. Exploiting a Weak CD Effect for Assignment of Configuration. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 1975–1978.

- Zhou, X.; Lu, Y.; Lin, X.; Yang, B.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y. Brominated aliphatic hydrocarbons and sterols from the sponge Xestospongia testudinaria with their bioactivities. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2011, 164, 703–706.

- Liu, Y.; Ding, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, X.; He, S. New antifungal tetrahydrofuran derivatives from a marine sponge-associated fungus Aspergillus sp. LS78. Fitoterapia 2020, 146, 104677.

- Cueto, M.; Darias, J. Uncommon tetrahydrofuran monoterpenes from Antarctic Pantoneura plocamioides. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 5899–5906.

- Blanc, A.; Toste, F.D. Enantioselective Synthesis of Cyclic Ethers through a Vanadium-Catalyzed Resolution/Oxidative Cyclization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 2096–2099.

- Darias, J.; Rovirosa, J.; San Martin, A.; Díaz, A.-R.; Dorta, E.; Cueto, M. Furoplocamioids A− C, Novel Polyhalogenated Furanoid Monoterpenes from Plocamium c artilagineum. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1383–1387.

- Díaz-Marrero, A.R.; Cueto, M.; Dorta, E.; Rovirosa, J.; San-Martín, A.; Darias, J. New halogenated monoterpenes from the red alga Plocamium cartilagineum. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 8539–8542.

- Argandoña, V.H.; Rovirosa, J.; San-Martín, A.; Riquelme, A.; Díaz-Marrero, A.R.; Cueto, M.; Darias, J.; Santana, O.; Guadaño, A.; González-Coloma, A. Antifeedant Effects of Marine Halogenated Monoterpenes. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2002, 50, 7029–7033.

- Raju, R.; Piggott, A.M.; Barrientos Diaz, L.X.; Khalil, Z.; Capon, R.J. Heronapyrroles A−C: Farnesylated 2-Nitropyrroles from an Australian Marine-Derived Streptomyces sp. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 5158–5161.

- Schmidt, J.; Khalil, Z.; Capon, R.J.; Stark, C.B. Heronapyrrole D: A case of co-inspiration of natural product biosynthesis, total synthesis and biodiscovery. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 1228–1232.

- Schmidt, J.; Stark, C.B.W. Biomimetic Synthesis and Proposal of Relative and Absolute Stereochemistry of Heronapyrrole C. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 4042–4045.

- Schmidt, J.; Stark, C.B.W. Synthetic Endeavors toward 2-Nitro-4-Alkylpyrroles in the Context of the Total Synthesis of Heronapyrrole C and Preparation of a Carboxylate Natural Product Analogue. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 1920–1928.

- Ding, X.-B.; Furkert, D.P.; Capon, R.J.; Brimble, M.A. Total Synthesis of Heronapyrrole C. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 378–381.

- Ding, X.-B.; Brimble, M.A.; Furkert, D.P. Nitropyrrole natural products: Isolation, biosynthesis and total synthesis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 5390–5401.

- Ding, X.-B.; Furkert, D.P.; Brimble, M.A. 2-Nitropyrrole cross-coupling enables a second generation synthesis of the heronapyrrole antibiotic natural product family. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 12638–12641.

- Ding, X.-B.; Brimble, M.A.; Furkert, D.P. Reactivity of 2-Nitropyrrole Systems: Development of Improved Synthetic Approaches to Nitropyrrole Natural Products. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 12460–12470.

- Suzuki, T.; Koizumi, K.; Suzuki, M.; Kurosawa, E. Kumausalle, a new bromoallene from the marine red alga laurencia nipponica yamada. Chem. Lett. 1983, 12, 1639–1642.

- Grese, T.A.; Hutchinson, K.D.; Overman, L.E. General approach to halogenated tetrahydrofuran natural products from red algae of the genus Laurencia. Total synthesis of (.+-.)-kumausallene and (.+-.)-1-epi-kumausallene. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 2468–2477.

- Werness, J.B.; Tang, W. Stereoselective Total Synthesis of (−)-Kumausallene. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 3664–3666.

- Das, S.; Ramana, C.V. A formal total synthesis of (−)-kumausallene. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 8577–8584.

- Suzuki, T.; Koizumi, K.; Suzuki, M.; Kurosawa, E. Kumausynes and deacetylkumausynes, four new halogenated C-15 acetylenes from the red alga Laurencia nipponica Yamada. Chem. Lett. 1983, 12, 1643–1644.

- Brown, M.J.; Harrison, T.; Overman, L.E. General approach to halogenated tetrahydrofuran natural products from red algae of the genus Laurencia. Total synthesis of (.+-.)-trans-kumausyne and demonstration of an asymmetric synthesis strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 5378–5384.

- Von Salm, J.L.; Witowski, C.G.; Fleeman, R.M.; McClintock, J.B.; Amsler, C.D.; Shaw, L.N.; Baker, B.J. Darwinolide, a New Diterpene Scaffold That Inhibits Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm from the Antarctic Sponge Dendrilla membranosa. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 2596–2599.

- Shilling, A.J.; Witowski, C.G.; Maschek, J.A.; Azhari, A.; Vesely, B.A.; Kyle, D.E.; Amsler, C.D.; McClintock, J.B.; Baker, B.J. Spongian Diterpenoids Derived from the Antarctic Sponge Dendrilla antarctica Are Potent Inhibitors of the Leishmania Parasite. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 1553–1562.

- Siemon, T.; Steinhauer, S.; Christmann, M. Synthesis of (+)-Darwinolide, a Biofilm-Penetrating Anti-MRSA Agent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1120–1122.

- Rodríguez, A.D.; Piña, I.C.; Soto, J.J.; Rojas, D.R.; Barnes, C.L. Isolation and structures of the uprolides. I. Thirteen new cytotoxic cembranolides from the Caribbean gorgonian Euniceamammosa. Can. J. Chem. 1995, 73, 643–654.

- Rodríguez, A.D.; Soto, J.J.; Piña, I.C. Uprolides D-G, 2. A Rare Family of 4,7-Oxa-bridged Cembranolides from the Caribbean Gorgonian Eunicea mammosa. J. Nat. Prod. 1995, 58, 1209–1216.

- Rodríguez, A.D.; Soto, J.J.; Barnes, C.L. Synthesis of Uprolide D− G Analogues. Revision of Structure of the Marine Cembranolides Uprolide F Diacetate and Uprolide G Acetate. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 7700–7702.

- Zhu, L.; Tong, R. Structural Revision of (+)-Uprolide F Diacetate Confirmed by Asymmetric Total Synthesis. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1966–1969.

- Zhu, L.; Liu, Y.; Ma, R.; Tong, R. Total Synthesis and Structural Revision of (+)-Uprolide G Acetate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 627–632.

- Zhu, L.; Tong, R. Structural Revision of Uprolide G Acetate: Effective Interplay between NMR Data Analysis and Chemical Synthesis. Synlett 2015, 26, 1643–1648.

- Ramana, C.V.; Salian, S.R.; Gurjar, M.K. Central core of uprolides D and E: A survey of some ring closing metathesis approaches. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 1013–1016.

- Marshall, J.A.; Griot, C.A.; Chobanian, H.R.; Myers, W.H. Synthesis of a Lactone Diastereomer of the Cembranolide Uprolide D. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4328–4331.

- Torres-Mendoza, D.; González, Y.; Gómez-Reyes, J.F.; Guzmán, H.M.; López-Perez, J.L.; Gerwick, W.H.; Fernandez, P.L.; Gutiérrez, M. Uprolides N, O and P from the Panamanian Octocoral Eunicea succinea. Molecules 2016, 21, 819.

More

Information

Subjects:

Chemistry, Medicinal

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Entry Collection:

Organic Synthesis

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Oct 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No