| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wee Yin Koh | -- | 4082 | 2022-10-21 05:31:40 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 4082 | 2022-10-21 06:05:32 | | |

Video Upload Options

The incorporation of probiotics in non-dairy matrices is challenging, and probiotics tend to have a low survival rate in these matrices and subsequently perform poorly in the gastrointestinal system. Encapsulation of probiotics with a physical barrier could preserve the survivability of probiotics and subsequently improve delivery efficiency to the host.

1. Introduction

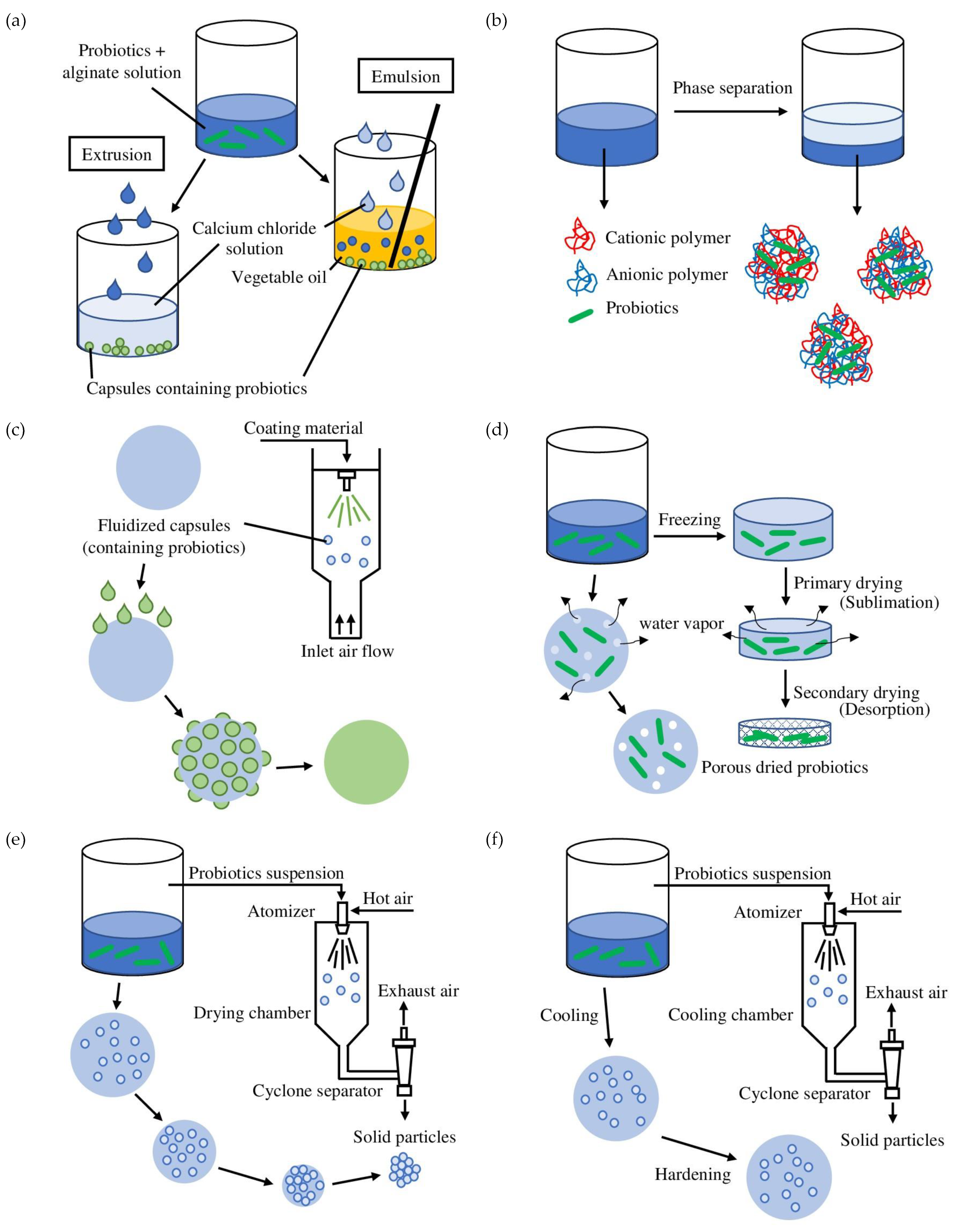

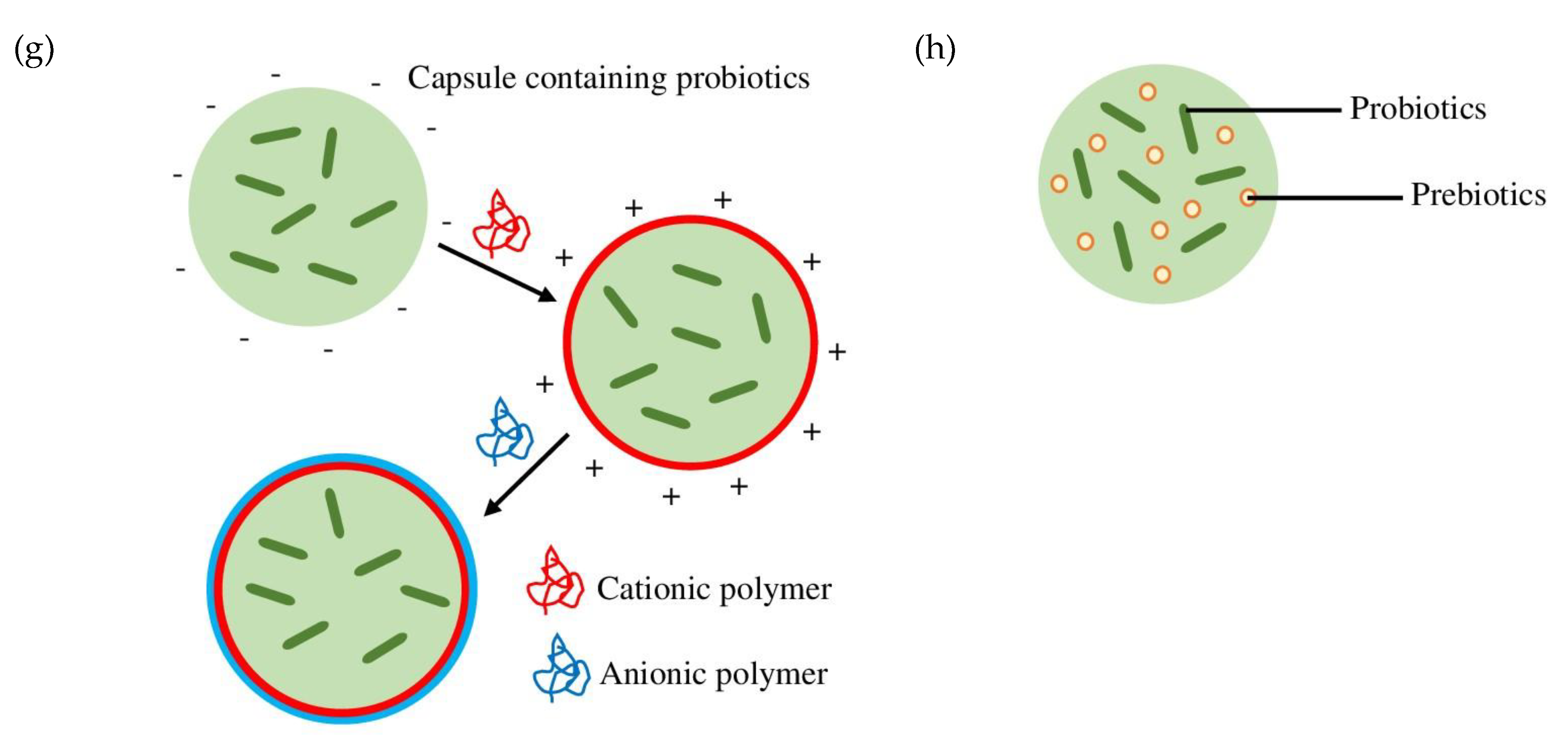

2. Encapsulation

3. Probiotic Encapsulation Techniques

|

Methods |

Properties of Encapsulation |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Extrusion (external ionic gelation) |

Produces capsules with sizes of 100 μm to 3 mm. Can encapsulate hydrophilic and hydrophobic/lipophilic compounds. |

Monodispersity. Simple and mild process.Can be conducted under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Low operation cost. High survival rate of probiotics. |

Produces relatively large beads.Slow solidification process. Not suitable for mass production. Additional drying process is required. |

|

|

Emulsion (internal ionic gelation) |

Produces capsules with sizes of 200 nm to 1 mm. Can encapsulate hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds. |

Simple process. Produces relatively small beads. Suitable for mass production. High survival rate of bacteria. |

Polydispersity. High operation cost. Conventional emulsions are thermodynamically unstable. Not suitable for low-fat food matrices. Additional drying process is required. |

|

|

Coacervation (complex coacervation) |

Produces capsules with sizes of 1 μm to 1 mm. Encapsulates hydrophobic compounds. |

Simple and mild process. Suitable for the food industry. High encapsulation efficiency. Controlled release potential. |

High operational cost. Not suitable for mass production.Animal-based protein is commonly used. Only stable at a narrow pH, ionic strength, and temperature range. |

|

|

Spray-drying |

Produces capsules with sizes of 5–150 μm. Encapsulateshydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds. |

Monodispersity. Fast, continuous process.L ow operation cost. Suitable for mass production. Produces dry beads with low bulk density, water activity, and high stability. |

Low cell viability. Produces beads with low uniformity.Biomaterials used have to be water-soluble. |

|

|

Freeze-drying |

Produces capsules with sizes of 1–1.5 mm. Encapsulates hydrophilic and hydrophobic/lipophilic compounds. |

Suitable for temperature-sensitive probiotics. Dried end product is suitable for most food applications. |

High operation cost. Not suitable for mass production. Cryoprotectants are needed. |

|

|

Spray chilling |

Produces capsules with sizes of 20–200 µm. Encapsulates hydrophobic compounds. |

Monodispersity. Fast, continuous, mild process. Low operation cost. Suitable for mass production.Promising in controlled release of probiotics. |

Low encapsulation efficiency. Rapid release of the encapsulated probiotics. Special storage conditions can be required. |

|

|

Fluidized bed coating |

Produces capsules with sizes of 5–5000 μm. Encapsulateshydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds. |

Mild process.Low operation cost. Suitable for mass production. Can provide multi-coating layers. Suitable for temperature-sensitive probiotics. |

Slow process. Probiotics have to be pre-encapsulated and dried. |

4. Biomaterials Utilized for Probiotics Encapsulation

|

Category |

Biomaterial |

Characteristics and Advantages |

Limitations |

Remarks |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Carbohydrate |

Alginates |

Anionic character, non-toxic, biocompatibility, biocompostability, cell affinity, strong bioadhesion, absorption characteristics, antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and low in cost. Stable (shrink) in the low acidic stomach gastric solution and gradually dissolve (swell and release encapsulated probiotics) under alkaline conditions in the small intestine. |

Sensitive to heat treatment, highly porous, poor stability and barrier properties. |

Technique: extrusion, emulsion.Could form a strong gel network by interacting with cationic material (e.g., chitosan). Combination: pectin, starch, chitosan. |

|

|

Chitosan |

Cationic character, non-toxic, biodegradability, bioadhesiveness, antimicrobial, antifungal, low in cost, high film-forming properties, great probiotics biocompatibility, resistance to the damaging effects of calcium chelating and anti-gelling agent, generate strong beads. |

Degrade easily in low pH conditions, water-insoluble at pH > 5.4. Pose inhibitory effect against lactic acid bacteria. |

Technique: extrusion, layer-by-layer (LbL), emulsion.Normally used as a coating rather than as a capsule. Combination: alginate, pectin. |

||

|

Starch and starch derivatives |

GRAS is abundant, low in cost, non-allergenic, and biodegradable. Could produce gels with strong but flexible structure, transparent, colorless, flavorless, and odorless gel that is semi-permeable to water, carbon dioxide, and oxygen. Resistant to pancreatic enzymes. Pose prebiotic properties. |

Exhibit high viscosity in solution. |

Technique: extrusion, emulsion. Combination: alginate. |

||

|

Cellulose and cellulose derivatives |

Abundant, low in cost, biodegradability, biocompatibility, tunable surface properties. Insoluble at pH ≤ 5 but soluble at pH ≥ 6, effective in delivering probiotics to the colon. |

Cannot form gel beads by extrusion technique. |

Technique: emulsion, spray-drying. Combination: alginate, protein. |

[56] |

|

|

Maltodextrin |

Non-toxic, bland in taste, abundant, low in cost, good solubility, low viscosity even at high solid content. Excellent thermal stability. Pose (moderate) prebiotic properties. |

Low emulsifying capacity. |

Technique: spray-drying. Combination: gum Arabic, sodium caseinate. |

||

|

Carrageenan (κ-carrageenan) |

Pose thermosensitive and thermoreversible characteristics, the probiotic release can be controlled with temperature. |

The gel beads produced are irregular in shape, brittle and weak, and their probiotic release rate is much slower than alginate beads. |

Technique: extrusion, emulsion. Dissolves at 80–90 °C. Addition of probiotics at 40–50 °C. Gelation at room temperature. Combination: milk protein, alginate, locust bean gum (LBG), carboxymethyl cellulose. |

||

|

Pectin |

Anionic character, abundant, non-toxic, water-soluble, biocompatibility, biodegradability, bioadhesiveness, antimicrobial, antiviral, good gelling, emulsifying, thickening and water binding properties, prebiotic effect. |

Low in thermal stability, poor mechanical properties. High water solubility. High concentration of sucrose contents. |

Technique: spray-drying. Combination: a variety of carbohydrate-based biomaterials. |

||

|

Gums |

Xanthan gum |

Anionic character, non-toxic, biodegradable, biocompatible, excellent gelling properties, highly soluble in both cold and hot water. Excellent heat and acid stability. Resistant to gastrointestinal digestion and enzymatic decomposition. Could also act as a source prebiotic. |

High susceptibility to microbial contamination, unstable viscosity, and uncontrollable hydration rate. Gels produced solely using xanthan gum are relatively weak. |

Technique: spray and freeze-drying. Combination: alginate, chitosan, gellan, and β-cyclodextrin. |

|

|

Gellan gum |

Anionic character, non-toxic, biocompatible, biodegradable, water-soluble, and low in cost. High resistance against heat, acidic environments, and enzymatic degradation. Swell at high pH. |

High gel-setting temperatures (80–90 °C) cause heat injuries to probiotics. |

Technique: spray-drying. Combination: gelatin, sodium caseinate, and alginate. |

||

|

Gum Arabic |

Anionic character, acid stability, highly water soluble, low in viscosity. Exhibit surface activity, foaming, and emulsifying abilities. Could prevent complete dehydration of probiotics during the drying process and storage. |

Restricted availability and high cost. Show only partial protection against oxygen. |

Technique: spray-drying. Combination: maltodextrin, gelatin, whey protein isolates. |

||

|

Animal-based proteins |

Gelatin |

Amphoteric character, could form complexes with anionic polymers. Could produce beads with strong structure and impermeable to oxygen. |

High solubility. |

Technique: extrusion, complex coacervation, spray chilling, spray-drying, lyophilization. Combination: alginate, pectin. |

|

|

Whey protein |

Amphoteric character, highly nutritious, high resistance and stability against pepsin digestion, great gelation properties, thermal stability, hydration, and emulsification properties. |

The gel beads or matrices produced are weak. |

Technique: extrusion. Combination: gum Arabic, pectin, maltodextrin. |

||

|

Milk protein (casein) |

Amphiphilic character, abundant, low in cost, possess excellent gelling and emulsifying properties, self-assembling properties, biocompatibility, biodegradability, produce gel beads with varying sizes (range from 1 to 1000 µm), higher density and better protection, high resistance to thermal denaturation (sodium caseinate). |

Immunogenicity and allergenicity. |

Technique: extrusion, emulsification, spray-drying, enzyme-induced gelation. Combination: a variety of carbohydrate-based biomaterials. |

||

|

Plant-based proteins |

Zein protein |

Amphiphilic character, biocompatible, biodegradable, water-insoluble, high resistance against gastric juice. |

Highly unstable, aggregate in aqueous solutions. |

Technique: electro-spinning, electro-spraying, spray-drying. Combination: sodium caseinate, alginate, pectin. |

[68] |

|

Soy protein |

High nutritional value, less allergenic, surface active, good emulsifying, absorbing, film forming properties, high resistance against gastric juice. |

Heat-induced gel formation. |

Technique: extrusion, spray-drying, coacervation. Combination: carrageenan, pectin. |

||

|

Lipids |

Natural waxes, vegetable oils, diglycerides, monoglycerides, fatty acids, resins |

Low in polarity, excellent water barrier properties, thermally stable, and could encapsulate hydrophilic substances. |

Weak mechanical properties, chemically unstable, might negatively affect the sensory characteristics of food products due to lipid oxidation. |

Technique: spray chilling, spray coating.Have melting points ranging from 50–85 °C. Combination: polysaccharides or proteins. |

[70] |

5. Application of Probiotics Encapsulation in Non-Dairy-Based Food and Beverage Products

|

Category |

Technology |

Probiotic/LAB Strain |

Encapsulating Agent |

Food Product |

Results |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fruit and vegetable-based |

Emulsion |

Bifidobacterium bifidum |

60 mL sodium alginate, κ-carrageenan, 5 g Tween 80 |

Grape juice |

The viability of B. bifidum was enhanced from 6.58 log CFU/mL (free) to 8.51 log CFU/mL (sodium alginate-encapsulated) and 7.09 log CFU/mL (κ-carrageenan-encapsulated) after 35 days of storage. |

[7] |

|

Extrusion |

Enterococcus faecium |

2% (w/w) sodium alginate |

Cherry juice |

Encapsulated probiotics had higher viability during storage (4 and 25 °C) and stronger tolerance against heat, acid, and digestion treatments than free probiotics. |

[13] |

|

|

Emulsion |

Lactobacillus salivarius spp. salivarius CECT 4063 |

100 mL of sodium alginate (3%), 1 mL Tween 80 |

Apple matrix |

Encapsulated L. salivarius spp. Salivarius had higher survivability (3%) than those non-encapsulated (19%) after 30 days of storage. |

[10] |

|

|

Complex coacervation |

Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis |

6% whey protein concentrate, 1% gum Arabic, 5% (w/w) proanthocyanidin-rich cinnamon extract (bioactive compound) |

Sugar cane juice |

Co-encapsulation of compounds was effective in protecting the viability of B. animalis and the stability of proanthocyanidins during storage and allowing simultaneous delivery. |

[14] |

|

|

Emulsion |

Lactobacillus acidophilus PTCC1643, Bifidobacterium bifidum PTCC 1644 |

2% (v/w) sodium alginate, 5 g/L Span 80 emulsifier |

Grape juice |

The survivability of L. acidophilus and B. Bifidum in the encapsulated samples (8.67 and 8.27 log CFU/mL) was higher than free probiotics (7.57 and 7.53 log CFU/mL) after 60 days of storage at 4 °C. |

[15] |

|

|

Emulsion followed by coating |

Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus fermentum, Lactobacillus casei, Lysinibacillus sphaericus, Saccharomyces boulardii |

Emulsion: 20 mL of sodium alginate (2%), 0.1% Tween 80 Coating: 0.4% chitosan in acidified distilled water |

Tomato and carrot juices |

Encapsulated probiotics had higher viability than free probiotics during storage of 5–6 weeks at 4 °C. Lys. sphaericus was observed to have higher viability and stability than other probiotics. |

[16] |

|

|

Co-encapsulation (extrusion) |

Lactococcus lactis ABRIINW-N19 |

1.5, 2% alginate-0.5% Persian gum (hydrogels), 1, 1.5, 2% fructooligosaccharides (FOS; prebiotic), and 1, 1.5, 2% inulin (prebiotic) |

Orange juice |

All formulations used were able to retain the viability of L. lactis during 6 weeks of storage at 4 °C. Encapsulated L. lactis were only released after 2 h and remained stable for up to 12 h in colonic conditions. |

[17] |

|

|

Vibrating nozzle method (evolved extrusion) |

Lactobacillus casei DSM 20011 |

2% sodium alginate |

Pineapple, raspberry, and orange juices |

After 28 days of storage at 4 °C, some microcapsules were observed as broken in pineapple juice, but the viability was 100% (2.3 × 107 CFU/g spheres). 91% viability (5.5 × 106 CFU/g spheres) was observed in orange juice. Raspberry juice was not a suitable medium for L. casei. |

[18] |

|

|

Co-encapsulation (spray-drying) |

Lactobacillus reuteri |

60 g maltodextrin, 0−2% gelatin |

Passion fruit juice powder |

The use of gelatin in combination with maltodextrin was more efficient in maintaining the cellular viability and retention of phenolic compounds than maltodextrin alone. |

[19] |

|

|

Spray-drying |

Lactobacillus plantarum |

0.5% (w/w) magnesium carbonate, 12% (w/w) maltodextrin |

Sohiong (Prunus nepalensis L.) juice powder |

The quality of probiotic Sohiong juice powder and viability of L. plantarum (6.12 log CFU/g) could be maintained for 36 days without refrigeration (25 °C and 50% relative humidity). |

[20] |

|

|

Fluidized bed drying |

Bacillus coagulans |

Mixture of 0.0125 g/mL hydroxyethyl cellulose and 1.17 µL/mL polyethylene glycol |

Dried apple snack |

Encapsulated Bacillus coag-ulans in dried apple snacks had high viability (>8 log CFU/portion) after 90 days of storage at 25 °C. |

[11] |

|

|

Extrusion |

Lactobacillus plantarum |

Mixtures (1:2, 1:4, 1:8, 1:12) of 4% (w/v) sodium alginate and 20% (w/v) soy protein isolate |

Mango juice |

Homogenous aqueous solutions of alginate and soy protein isolate (1:8) increased the thermal resistance of L. plantarum against pasteurization process. The viability of L. plantarum remained high after the pasteurization process (8.11 log CFU/mL; reduced 0.99 log CFU/mL). |

[21] |

|

|

Layer-by-layer (Coating) |

Lactobacillus plantarum 299v |

First layer: 1% (w/v) carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and 50% w/w (based on CMC weight) glycerol; Second layer: 5% (w/v) zein protein |

Apple slices |

The viability of CMC-zein protein-coated L. plantarum 299v was higher than CMC-coated L. plantarum 299v in apple slices under simulated gastrointestinal conditions (120 min digestion; CMC-zein protein-coated: 1.00 log CFU/g reduction, CMC-coated: 2.18 log CFU/g reduction). |

[12] |

|

|

Complex coacervation (associated with enzymatic crosslinking) |

Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-02 |

Complex co-acervation: 2.5% gelatin, 2.5% gum Arabic; Crosslinking: 2.5, 5.0 U/g transglutaminase |

Apple and orange juices |

Encapsulated L. acidophilus LA-02 incorporated in fruit juices was able to survive throughout the storage period of 63 days (4 °C). |

[22] |

|

|

Freeze-drying, spray-drying |

Enterococcus faecalis (K13) |

Gum Arabic and maltodextrin |

Carrot juice powder |

Heat injuries to the probiotics are lower in the freeze-drying technique compared to spray-drying. After being stored for 1 month, the viability of freeze-dried E. faecalis remained high (6–7 log CFU/g). |

[23] |

|

|

Spray-drying |

Lactobacillus casei Shirota, Lactobacillus casei Immunitas, and Lactobacillus acidophilus Johnsonii |

Maltodextrin and pectin at weight ratio of 10:1 |

Orange juice powder |

The combination of pectin and maltodextrins effectively protected the probiotics during the spray-drying process and storage (4 °C) |

[24] |

|

|

Freeze-drying |

Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei |

Whey protein isolate, fructooligosaccharides, and combination of whey protein isolate, fructooligosaccharides (1:1) |

Banana powder |

L. acidophilus and L. casei encapsulated with the combination of whey protein isolate and fructooligosaccharides had higher survivability after being stored for 30 days at 4 °C and more resistant to the simulated gastric fluid intestinal fluid than free probiotics. |

[25] |

|

|

Fluidized bed drying |

Lactobacillus plantarum TISTR 2075 |

3% (w/w) gelatin and 5% (w/w) of monosodium glutamate, maltodextrin, inulin, and fructooligosaccharide |

Carrot tablet |

Encapsulated L. plantarum TISTR 2075 in carrot tablet (survivability: 77.68–87.30%) had higher tolerance against heat digestion treatments than free cells (39.52%). |

[26] |

|

|

Other beverages |

Spray-drying |

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) |

Mixtures (1:1.6 (w/w)) of 7.5% (w/v) whey protein isolate and 20% (w/v) modified huauzontle’s starch (acid hydrolysis-extrusion), supplemented with ascorbic acid |

Green tea beverage |

The viability of LGG remained above the recommended 7 log CFU/mL after 5 weeks of storage at 4 °C. |

[28] |

|

Co-encapsulation (extrusion) |

Lactobacillus acidophilus TISTR 2365 |

Alginate, egg (0, 0.8, 1, and 3%, w/v), and fruiting body of bamboo mushroom (prebiotic) |

Sweet fermented rice (Khoa-Mak) sap beverage |

All formulations used were able to provide high encapsulation yields (95.72−98.86%) and high viability of L. acidophilus (>8 log CFU/g) in Khoa-Mak sap beverages for 35 days of storage at 4 °C. Encapsulation with involvement of 3% egg of bamboo mushroom increased the survival of L. acidophilus the most. |

[27] |

|

|

Co-encapsulation (extrusion) |

Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM (L-NCFM) |

Co-extrusion: 0–2% (w/v) LBG, 0–5% (w/v) mannitol (prebiotic) Coating: sodium alginate |

Mulberry tea |

L-NCFM encapsulated with LBG and mannitol (0.5% (w/v) and 3% (w/v), respectively) showed microencapsulation efficiency and viability of 96.81% and 8.92 log CFU/mL, respectively. Among other samples, L-NCFM microencapsulated with mannitol showed the highest survivability (78.89%) and viable count (6.80 log CFU/mL) after 4 weeks of storage at 4 and 25 °C. |

[29] |

|

|

Bakery products |

Double-layered microencapsulation, combination of spray chilling and spray-drying |

Saccharomyces boulardii, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum |

Spray chilling: 5% (v/w) blend of gum Arabic and β-cyclodextrin solution (9:1 (w/w), 20 g in total), 1% lecithin Spray-drying: 5% (v/w) blend of gum Arabic and β-cyclodextrin solution, 20 g hydrogenated palm oil, 2% Tween 80 emulsifier |

Cake |

The survivability of probiotics during the cake baking process was improved by double-layered microencapsulation. |

[31] |

|

Fluidized bed drying |

Lactobacillus sporogenes |

First layer: 10 g microcrystalline cellulose powder and alginate or xanthan gum Second layer: gellan or chitosan |

Bread |

Encapsulated L. sporogenes in alginate (1%) capsule tolerated the simulated gastric acid condition the best. The incorporation of chitosan (0.5%) as an outer layer improved the heat tolerance of L. sporogenes. Encapsulated L. sporogenes with an outer layer coated with 1.5% gellan showed the highest survivability 24 h after baking. |

[32] |

|

|

Emulsion |

Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356 |

1. Alginate 2%; 2. Alginate 2% + maltodextrin 1%; 3. Alginate 2% + xanthan gum 0.1%; 4. Alginate 2% + maltodextrin 1% + 0.1% xanthan gum |

Bread |

Among the encapsulation agents, probiotics encapsulated using the combination of maltodextrin, xanthan gum, and alginate (4) had the highest survivability under storage (7.7 log CFU/bread) and simulated gastrointestinal conditions. |

[33] |

|

|

Sauce |

Co-encapsulation (extrusion) |

Lactobacillus casei Lc-01, Lactobacillus acidophilus La5 |

4% (w/v) sodium alginate and 2% alginate mixture in distilled watercontaining 2% high amylose maize starch (prebiotic), 0.2% Tween 80 |

Mayonnaise |

The viability of L. casei and L. acidophilus encapsulated with high amylose maize starch (7.204 and 8.45 log CFU/mL, respectively) was higher than free probiotics (6.23 and 6.039 log CFU/mL, respectively) and those without high amylose maize starch (7.1 and 7.94 log CFU/mL, respectively) after 91 days of storage at 4°C. |

[35] |

|

Others |

Extrusion followed by freeze-drying |

Lactobacillus casei (L. casei 431) |

3% (w/v) quince seed gum, sodium alginate, quince seed gum-sodium alginate |

Powdered functional drink |

Quince seed gum-alginate microcapsules provided encapsulation efficiency of 95.20% and increased the survival rate of L. casei to 87.56%. The powdered functional drink was shelf stable for 2 months. |

[37] |

|

Spray chilling |

Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis |

Vegetable fat (Tri-HS-48) |

Savory cereal bars |

The viabilities of spray-chilled probiotics were higher than freeze-dried and free probiotics in the savory cereal bars after being stored for 90 days at 4 °C. |

[34] |

|

|

Co-encapsulation (extrusion) |

Lactobacillus reuteri |

2% (w/v) sodium alginate, 5 mL of inulin and lecithin solution (0, 0.5, and 1%) |

Chewing gum |

After storing for 21 days with encapsulation, L. reuteri remained viable. The viability of the probiotic increased with the concentration of inulin and lecithin. |

[36] |

References

- Sarao, L.K.; Arora, M. Probiotics, prebiotics, and microencapsulation: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 344–371.

- Min, M.; Bunt, C.R.; Mason, S.L.; Hussain, M.A. Non-dairy probiotic food products: An emerging group of functional foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2626–2641.

- FAO/WHO. FAO/WHO Joint Working Group Report on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food (30 April 2002 and 1 May 2002); Scientific Research Publishing: London, ON, Canada, 2002.

- Sanders, M.E.; Goh, Y.J.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Probiotics and Prebiotics. In Food Microbiology: Fundamentals and Frontiers; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 831–854.

- Murua-Pagola, B.; Castro-Becerra, A.L.; Abadia-Garcia, L.; Castano-Tostado, E.; Amaya-Llano, S.L. Protective effect of a cross-linked starch by extrusion on the survival of Bifidobacterium breve ATCC 15700 in yogurt. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15097.

- da Silva, M.N.; Tagliapietra, B.L.; dos Santos Richards, N.S.P. Encapsulation, storage viability, and consumer acceptance of probiotic butter. LWT 2021, 139, 110536.

- Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Saeed, M.; Ahmed, A.; Ateeq, H.; Nadeem, M.T.; Tufail, T. Survival and stability of free and encapsulated probiotic bacteria under simulated gastrointestinal conditions and in pasteurized grape juice. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14346.

- Thamacharoensuk, T.; Boonsom, T.; Tanasupawat, S.; Dumkliang, E. Optimization of microencapsulated Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG from whey protein and glutinous rice starch by spray drying. Key Eng. Mater. 2020, 859, 265–270.

- Aspri, M.; Papademas, P.; Tsaltas, D. Review on non-dairy probiotics and their use in non-dairy based products. Fermentation 2020, 6, 30.

- Ester, B.; Noelia, B.; Laura, C.-J.; Francesca, P.; Cristina, B.; Rosalba, L. Probiotic survival and in vitro digestion of L. salivarius spp. salivarius encapsulated by high homogenization pressures and incorporated into a fruit matrix. LWT 2019, 111, 883–888.

- Galvão, A.M.; Rodrigues, S.; Fernandes, F.A. Probiotic dried apple snacks: Development of probiotic coating and shelf-life studies. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14974.

- Wong, C.H.; Mak, I.E.K.; Li, D. Bilayer edible coating with stabilized Lactobacillus plantarum 299v improved the shelf life and safety quality of fresh-cut apple slices. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 30, 100746.

- Azarkhavarani, P.R.; Ziaee, E.; Hosseini, S.M.H. Effect of encapsulation on the stability and survivability of Enterococcus faecium in a non-dairy probiotic beverage. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 25, 233–242.

- Holkem, A.T.; Neto, E.J.S.; Nakayama, M.; Souza, C.J.; Thomazini, M.; Gallo, F.A.; Favaro-Trindade, C.S. Sugarcane juice with co-encapsulated Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BLC1 and proanthocyanidin-rich cinnamon extract. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 1179–1192.

- Mokhtari, S.; Jafari, S.M.; Khomeiri, M. Survival of encapsulated probiotics in pasteurized grape juice and evaluation of their properties during storage. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 25, 120–129.

- Naga Sivudu, S.; Ramesh, B.; Umamahesh, K.; Vijaya Sarathi Reddy, O. Probiotication of tomato and carrot juices for shelf-life enhancement using micro-encapsulation. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 13–22.

- Nami, Y.; Lornezhad, G.; Kiani, A.; Abdullah, N.; Haghshenas, B. Alginate-persian gum-prebiotics microencapsulation impacts on the survival rate of Lactococcus lactis ABRIINW-N19 in orange juice. LWT 2020, 124, 109190.

- Olivares, A.; Soto, C.; Caballero, E.; Altamirano, C. Survival of microencapsulated Lactobacillus casei (prepared by vibration technology) in fruit juice during cold storage. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 42, 42–48.

- Santos Monteiro, S.; Albertina Silva Beserra, Y.; Miguel Lisboa Oliveira, H.; Pasquali, M.A.d.B. Production of probiotic passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims f. Flavicarpa Deg.) drink using Lactobacillus reuteri and microencapsulation via spray drying. Foods 2020, 9, 335.

- Vivek, K.; Mishra, S.; Pradhan, R.C. Characterization of spray dried probiotic Sohiong fruit powder with Lactobacillus plantarum. LWT 2020, 117, 108699.

- Praepanitchai, O.-A.; Noomhorm, A.; Anal, A.K. Survival and behavior of encapsulated probiotics (Lactobacillus plantarum) in calcium-alginate-soy protein isolate-based hydrogel beads in different processing conditions (pH and temperature) and in pasteurized mango juice. Biomed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 9768152.

- da Silva, T.M.; Pinto, V.S.; Soares, V.R.F.; Marotz, D.; Cichoski, A.J.; Zepka, L.Q.; Lopes, E.J.; da Silva, C.B.; de Menezes, C.R. Viability of microencapsulated Lactobacillus acidophilus by complex coacervation associated with enzymatic crosslinking under application in different fruit juices. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110190.

- Rishabh, D.; Athira, A.; Preetha, R.; Nagamaniammai, G. Freeze dried probiotic carrot juice powder for better storage stability of probiotic. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 1–9.

- Gervasi, C.; Pellizzeri, V.; Vecchio, G.L.; Vadalà, R.; Foti, F.; Tardugno, R.; Cicero, N.; Gervasi, T. From by-product to functional food: The survival of L. casei shirota, L. casei immunitas and L. acidophilus johnsonii, during spray drying in orange juice using a maltodextrin/pectin mixture as carrier. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 1–8.

- Massounga Bora, A.F.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Du, L. Improved viability of microencapsulated probiotics in a freeze-dried banana powder during storage and under simulated gastrointestinal tract. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 1330–1339.

- Nilubol, S.; Wanchaitanawong, P. Viability of Lactobacillus plantarum TISTR 2075 in carrot tablet after fluidized bed drying. In Proceedings of the The National and International Graduate Research Conference, Khon Kaen, Thailand, 10 March 2017; pp. 155–165.

- Srisuk, N.; Nopharatana, M.; Jirasatid, S. Co-encapsulation of Dictyophora indusiata to improve Lactobacillus acidophilus survival and its effect on quality of sweet fermented rice (Khoa-Mak) sap beverage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 3598–3610.

- Hernández-Barrueta, T.; Martínez-Bustos, F.; Castaño-Tostado, E.; Lee, Y.; Miller, M.J.; Amaya-Llano, S.L. Encapsulation of probiotics in whey protein isolate and modified huauzontle’s starch: An approach to avoid fermentation and stabilize polyphenol compounds in a ready-to-drink probiotic green tea. LWT 2020, 124, 109131.

- Yee, W.L.; Yee, C.L.; Lin, N.K.; Phing, P.L. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM incorporated with mannitol and its storage stability in mulberry tea. Cienc. Agrotecnologia 2019, 43, 1–11.

- Wulandari, N.; Suharna, N.; Yulinery, T.; Nurhidayat, N. Probiotication of black grass jelly by encapsulated Lactobacillus plantarum Mar8 for a ready to drink (RTD) beverages. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2019, 15, 375–386.

- Arslan-Tontul, S.; Erbas, M.; Gorgulu, A. The use of probiotic-loaded single-and double-layered microcapsules in cake production. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 840–849.

- Mirzamani, S.; Bassiri, A.; Tavakolipour, H.; Azizi, M.; Kargozari, M. Fluidized bed microencapsulation of Lactobacillus sporogenes with some selected hydrocolloids for probiotic bread production. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 23–34.

- Thang, T.D.; Hang, H.T.T.; Luan, N.T.; KimThuy, D.T.; Lieu, D.M. Survival survey of Lactobacillus acidophilus in additional probiotic bread. TURJAF 2019, 7, 588–592.

- Bampi, G.B.; Backes, G.T.; Cansian, R.L.; de Matos, F.E.; Ansolin, I.M.A.; Poleto, B.C.; Corezzolla, L.R.; Favaro-Trindade, C.S. Spray chilling microencapsulation of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis and its use in the preparation of savory probiotic cereal bars. Food Bioproc. Technol. 2016, 9, 1422–1428.

- Bigdelian, E.; Razavi, S. Evaluation of survival rate and physicochemical properties of encapsulated bacteria in alginate and resistant starch in mayonnaise sauce. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2014, 4, 1.

- Qaziyani, S.D.; Pourfarzad, A.; Gheibi, S.; Nasiraie, L.R. Effect of encapsulation and wall material on the probiotic survival and physicochemical properties of synbiotic chewing gum: Study with univariate and multivariate analyses. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02144.

- Jouki, M.; Khazaei, N.; Rashidi-Alavijeh, S.; Ahmadi, S. Encapsulation of Lactobacillus casei in quince seed gum-alginate beads to produce a functional synbiotic drink powder by agro-industrial by-products and freeze-drying. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 120, 106895.

- Kumar, B.V.; Vijayendra, S.V.N.; Reddy, O.V.S. Trends in dairy and non-dairy probiotic products-a review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 6112–6124.

- Oberoi, K.; Tolun, A.; Sharma, K.; Sharma, S. Microencapsulation: An overview for the survival of probiotic bacteria. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2021, 2021, 280–287.

- Pech-Canul, A.d.l.C.; Ortega, D.; García-Triana, A.; González-Silva, N.; Solis-Oviedo, R.L. A brief review of edible coating materials for the microencapsulation of probiotics. Coatings 2020, 10, 197.

- Yao, M.; Xie, J.; Du, H.; McClements, D.J.; Xiao, H.; Li, L. Progress in microencapsulation of probiotics: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 857–874.

- Frakolaki, G.; Giannou, V.; Kekos, D.; Tzia, C. A review of the microencapsulation techniques for the incorporation of probiotic bacteria in functional foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1515–1536.

- Rodrigues, F.; Cedran, M.; Bicas, J.; Sato, H. Encapsulated probiotic cells: Relevant techniques, natural sources as encapsulating materials and food applications-a narrative review. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 1016.

- Khalil, K.A. A review on microencapsulation in improving probiotic stability for beverages application. Sci. Lett. 2020, 14, 49–61.

- Maciel, M.I.S.; de Souza, M.M.B. Prebiotics and Probiotics-Potential Benefits in Human Nutrition and Health. In Prebiotics and Probiotics-Potential Benefits in Nutrition and Health; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020.

- Timilsena, Y.P.; Akanbi, T.O.; Khalid, N.; Adhikari, B.; Barrow, C.J. Complex coacervation: Principles, mechanisms and applications in microencapsulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 1276–1286.

- Halim, M.; Mustafa, N.A.M.; Othman, M.; Wasoh, H.; Kapri, M.R.; Ariff, A.B. Effect of encapsulant and cryoprotectant on the viability of probiotic Pediococcus acidilactici ATCC 8042 during freeze-drying and exposure to high acidity, bile salts and heat. LWT 2017, 81, 210–216.

- Singh, P.; Medronho, B.; Miguel, M.G.; Esquena, J. On the encapsulation and viability of probiotic bacteria in edible carboxymethyl cellulose-gelatin water-in-water emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 75, 41–50.

- Haffner, F.B.; Diab, R.; Pasc, A. Encapsulation of probiotics: Insights into academic and industrial approaches. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2016, 3, 114–136.

- Liu, H.; Cui, S.W.; Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Liang, R.; Xu, F.; Zhong, F. Protective approaches and mechanisms of microencapsulation to the survival of probiotic bacteria during processing, storage and gastrointestinal digestion: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2863–2878.

- Broeckx, G.; Vandenheuvel, D.; Claes, I.J.; Lebeer, S.; Kiekens, F. Drying techniques of probiotic bacteria as an important step towards the development of novel pharmabiotics. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 505, 303–318.

- Gheorghita Puscaselu, R.; Lobiuc, A.; Dimian, M.; Covasa, M. Alginate: From food industry to biomedical applications and management of metabolic disorders. Polymers 2020, 12, 2417.

- Martău, G.A.; Mihai, M.; Vodnar, D.C. The use of chitosan, alginate, and pectin in the biomedical and food sector-biocompatibility, bioadhesiveness, and biodegradability. Polymers 2019, 11, 1837.

- Călinoiu, L.-F.; Ştefănescu, B.E.; Pop, I.D.; Muntean, L.; Vodnar, D.C. Chitosan coating applications in probiotic microencapsulation. Coatings 2019, 9, 194.

- Pavli, F.; Tassou, C.; Nychas, G.-J.E.; Chorianopoulos, N. Probiotic incorporation in edible films and coatings: Bioactive solution for functional foods. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 150.

- Mettu, S.; Hathi, Z.; Athukoralalage, S.; Priya, A.; Lam, T.N.; Ong, K.L.; Lin, C.S.K. Perspective on constructing cellulose-hydrogel-based gut-like bioreactors for growth and delivery of multiple-strain probiotic bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 4946–4959.

- Arepally, D.; Goswami, T.K. Effect of inlet air temperature and gum Arabic concentration on encapsulation of probiotics by spray drying. LWT 2019, 99, 583–593.

- Kwiecień, I.; Kwiecień, M. Application of polysaccharide-based hydrogels as probiotic delivery systems. Gels 2018, 4, 47.

- Lara-Espinoza, C.; Carvajal-Millán, E.; Balandrán-Quintana, R.; López-Franco, Y.; Rascón-Chu, A. Pectin and pectin-based composite materials: Beyond food texture. Molecules 2018, 23, 942.

- Noreen, A.; Akram, J.; Rasul, I.; Mansha, A.; Yaqoob, N.; Iqbal, R.; Zia, K.M. Pectins functionalized biomaterials; a new viable approach for biomedical applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 254–272.

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Bai, L.; Deng, J.; Zhou, Q. Biomaterial-based encapsulated probiotics for biomedical applications: Current status and future perspectives. Mater. Des. 2021, 210, 110018.

- Patel, J.; Maji, B.; Moorthy, N.H.N.; Maiti, S. Xanthan gum derivatives: Review of synthesis, properties and diverse applications. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 27103–27136.

- Razavi, S.; Janfaza, S.; Tasnim, N.; Gibson, D.L.; Hoorfar, M. Microencapsulating polymers for probiotics delivery systems: Preparation, characterization, and applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 120, 106882.

- Al-Hassan, A. Gelatin from camel skins: Extraction and characterizations. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 101, 105457.

- Li, X.; Chen, W.; Jiang, J.; Feng, Y.; Yin, Y.; Liu, Y. Functionality of dairy proteins and vegetable proteins in nutritional supplement powders: A review. Int. Food Res. J. 2019, 26, 1651–1664.

- Minj, S.; Anand, S. Whey proteins and its derivatives: Bioactivity, functionality, and current applications. Dairy 2020, 1, 233–258.

- Abd El-Salam, M.H.; El-Shibiny, S. Preparation and properties of milk proteins-based encapsulated probiotics: A review. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2015, 95, 393–412.

- Fathi, M.; Donsi, F.; McClements, D.J. Protein-based delivery systems for the nanoencapsulation of food ingredients. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 920–936.

- Dong, Q.Y.; Chen, M.Y.; Xin, Y.; Qin, X.Y.; Cheng, Z.; Shi, L.E.; Tang, Z.X. Alginate-based and protein-based materials for probiotics encapsulation: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 1339–1351.

- Nahum, V.; Domb, A.J. Recent developments in solid lipid microparticles for food ingredients delivery. Foods 2021, 10, 400.