| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Christelle Cauffiez | -- | 3640 | 2022-10-17 12:26:04 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | + 1 word(s) | 3641 | 2022-10-18 03:07:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

Fibrosis, or tissue scarring, is defined as the excessive, persistent and destructive accumulation of extracellular matrix components in response to chronic tissue injury. Renal fibrosis represents the final stage of most chronic kidney diseases and contributes to the progressive and irreversible decline in kidney function. The role of non-coding RNAs, and in particular microRNAs (miRNAs), has been described in kidney fibrosis.

1. Introduction

2. Non-Coding RNAs

2.1. microRNAs (miRNAs)

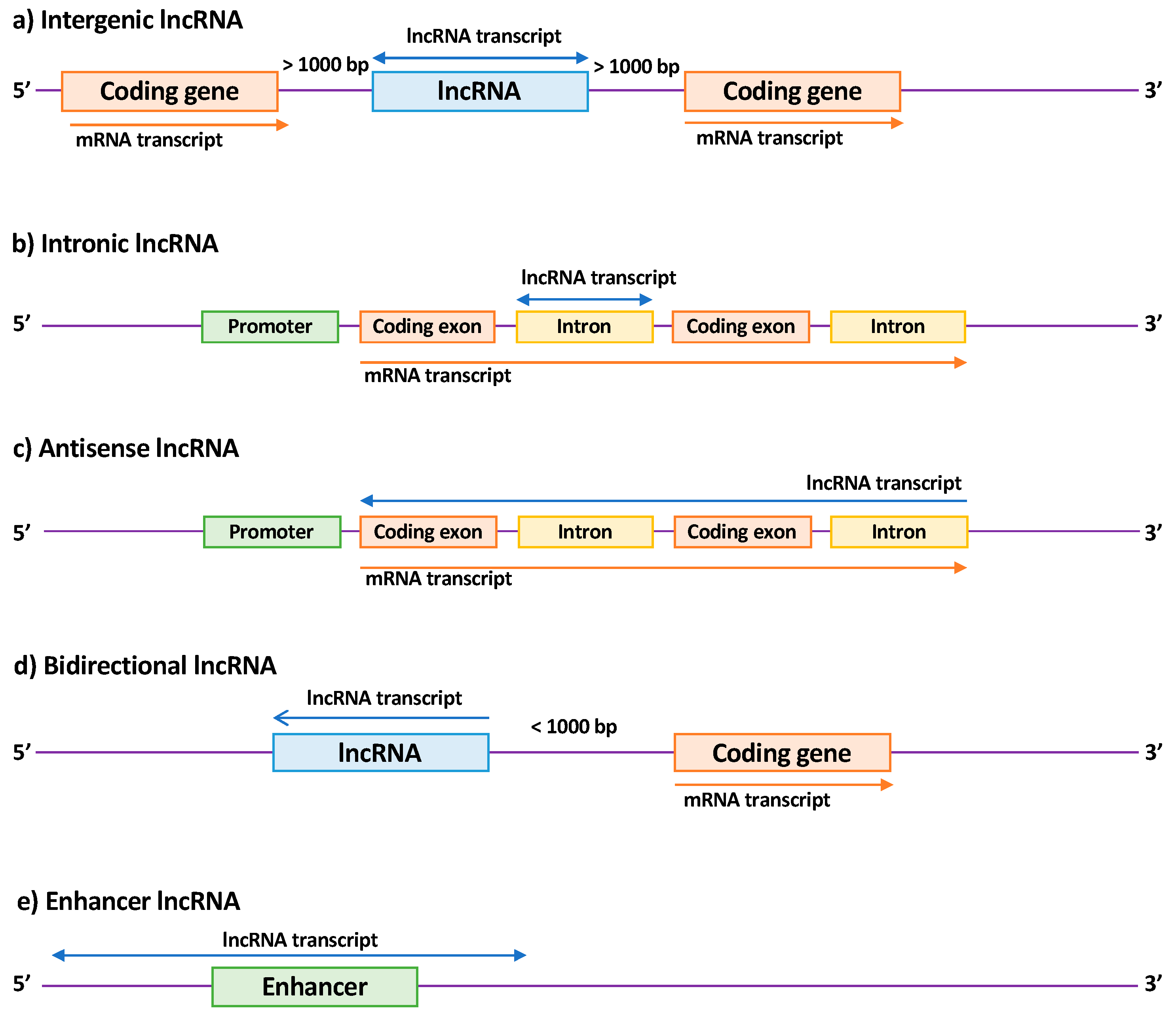

2.2. Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs)

3. miRNAs Implicated in Renal Fibrosis

|

Regulation |

miRNA |

Models |

Gene Target |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Up |

miR-21 |

Renal tissues from kidney transplanted patients Renal tissues from patients with IgA nephropathy Renal tissues from patients with Alport Syndrome UUO mouse model DN mouse model Ichemia reperfusion mouse model RPTEC cells Mesangial cells |

PTEN, SMAD7, PPARA, PDCD4, BCL2, PHD2, MKK3, RECK, TIMP3, THSP1, RAB11A |

[41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63] |

|

miR-22 |

DN rat model RPTEC cells |

PTEN |

[64] |

|

|

miR-135a |

Serum and renal tissues from patients with DN DN mouse model Mesangial cells |

TRPC1 |

[65] |

|

|

miR-150 |

renal tissue from patients with lupus nephritis RPTEC cells Mesangial cells |

SOCS1 |

[66] |

|

|

miR-155 |

UUO mouse model RPTEC cells |

PDE3A |

||

|

miR-184 |

UUO mouse models RPTEC cells |

HIF1AN |

[69] |

|

|

miR-214 |

UUO mouse model DN mouse model RPTEC cells Mesangial cells |

DKK3, CDH1, PTEN |

||

|

miR-215 |

DN mouse model Mesangial cells |

CTNNBIP1 |

[73] |

|

|

miR-216a |

DN mouse model Mesangial cells |

YBX1 |

[74] |

|

|

miR-324 |

Rat model of nephropathy (Munich Wistar Fromter rats) RPTEC cells |

PREP |

[75] |

|

|

miR-433 |

UUO mouse model RPTEC cells |

AZIN1 |

[76] |

|

|

miR-1207 |

RPTEC cells Mesangial cells |

G6PD, PMEPAI1, PDK1, SMAD7 |

[77] |

|

|

Down |

let-7 family |

DN mouse model RPTEC cells |

HMGA2, TGFBR1 |

|

|

miR-29 family |

UUO mouse model Adenine gavage in mice Chronic renal failure rat model (5/6e nephrectomy) DN mouse model RPTEC cells Endothelial cells Podcytes HEK293 treated with ochratoxin A |

COL, FN1, AGT, ADAM12, ADAM19, PIK3R2 |

||

|

miR-30 |

Renal tissues from kidney transplanted patients UUO mouse model DN mouse model RPTEC cells |

CTGF, KLF11, UCP2 |

||

|

miR-34 family |

UUO mouse model RPTEC cells |

NOTCH1/JAG1 |

[92] |

|

|

miR-152 |

RPTEC cells |

HPIP |

[93] |

|

|

miR-181 |

UUO mouse model |

EGR1 |

[94] |

|

|

miR-194 |

Ischemia reperfusion mouse model RPTEC cells |

RHEB |

[95] |

|

|

miR-200 family |

UUO mouse model Adenine gavage in mice RPTEC cells |

ZEB1/2, ETS1 |

||

|

miR-455 |

DN rat model RPTEC cells Mesangial cells |

ROCK2 |

[103] |

|

|

Down/Up (controversial) |

miR-192 |

UUO mouse model DN mouse model IgA nephropathy mouse model RPTEC cells |

ZEB1/2 |

Abbreviations: UUO (ureteral unilateral obstruction); RPTEC (renal proximal tubular epithelial cells); DN (diabetic nephropathy).

4. Long Non-Coding RNAs Implicated in Renal Fibrosis

|

Regulation |

lncRNA |

Models |

Functions/Mechanisms |

Consequences |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Up |

LOC105375913 |

Renal tissue of patients with segmental glomeruloscleoris RPTEC cells |

Binding to miR-27b and leading to Snail expression |

Pro-fibrotic |

[118] |

|

LINC00667 |

Renal tissue of patients with chronic renal failure Chronic renal failure rat model (partial nephrectomy) RPTEC cells |

Binding to Ago2, targeting miR-19b-3p |

Pro-fibrotic |

[119] |

|

|

NEAT1 |

DN rat model Mesangial cells |

Pro-fibrotic and increase of proliferation |

[120] |

||

|

Lnc-TSI (AP000695.6 or ENST00000429588.1) |

RPTEC cells UUO mouse model Ischemia-reperfusion mouse model Renal tissue of patients with IgA nephropathy |

Synergic binding to Smad3 |

Anti-fibrotic |

[121] |

|

|

HOTAIR |

UUO rat model RPTEC cells |

Acting as a ceRNA with miR-124: activation of Jagged1/Nocth1 signaling |

Pro-fibrotic |

||

|

LINC00963 |

Chronic renal failure rat model (5/6e nephrectomy) |

Inhibition of FoxO signaling pathway by targeting FoxO3a |

Pro-fibrotic |

[124] |

|

|

TCONS_00088786 |

UUO mouse model RPTEC cells |

Possibly regulation of miR-132 expression |

Pro-fibrotic |

[125] |

|

|

Errb4-IR (np-5318) |

UUO mouse model Anti GBM mouse model RPTEC cells DN mouse model Mesangial cells |

Downstream of TGFb/Smad3 pathway by binding Smad7 gene Binding to miR-29b |

Pro-fibrotic |

||

|

CHCHD4P4 |

Stone kidney mouse model RPTEC cells |

Pro-fibrotic |

[129] |

||

|

TCONS_00088786 |

UUO rat model RPTEC cells |

Pro-fibrotic |

[130] |

||

|

TCONS_01496394 |

UUO rat model RPTEC cells |

Pro-fibrotic |

[130] |

||

|

ASncmtRNA-2 |

DN mouse model Mesangial cells |

Pro-fibrotic |

[131] |

||

|

LincRNA-Gm4419 |

DN mouse model Mesangial cells |

Activation of NFkB/NLRP3 pathway by interacting with p50 |

Pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory |

||

|

H19 |

UUO mouse model RPTEC cells |

Acting as a ceRNA with miR-17 and fibronectin mRNA |

Pro-fibrotic |

[134] |

|

|

RP23.45G16.5 |

UUO mouse model RPTEC cells |

Pro-fibrotic |

[135] |

||

|

AI662270 |

UUO mouse model RPTEC cells |

No significative effect |

[135] |

||

|

Arid2-IR (np-28496) |

UUO mouse model RPTEC cells |

Smad3 binding site in Arid2-IR promoter Promoting NF-κB signaling |

Pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory effects |

[136] |

|

|

np-17856 |

UUO mouse model Glomerulonephritis mouse model |

Smad3 binding site |

Pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory |

[126] |

|

|

NR_033515 |

Serum of patients with diabetic nephropathy Mesangial cells |

Targeting miR-743b-5p |

Pro-fibrotic and promotes proliferation |

[137] |

|

|

MALAT1 |

DN mouse model Podocytes |

Binding to SRSF1 Targeting byβ-catenin |

Pro-fibrotic |

[138] |

|

|

Gm5524 |

DN mouse model Podocytes |

Autophagy increase and apoptosis decrease |

[139] |

||

|

WISP1-AS1 |

RPTEC cells |

Modulating ochratoxin-A-induced Egr-1 and E2F activities |

Cell viability increase |

[140] |

|

|

Down |

Gm15645 |

DN mouse model Podocytes |

Autophagy decrease and apoptosis increase |

[139] |

|

|

CYP4B1-PS1-001 (ENSMUST00000118753) |

DN mouse model Mesangial cells |

Enhancing ubiquitination and degradation of nucleolin |

Anti-fibrotic and anti-proliferative |

||

|

3110045C21Rik |

UUO mouse model RPTEC cells |

Anti-fibrotic |

[135] |

||

|

ENSMUST00000147869 |

DN mouse model Mesangial cells |

Associated with Cyp4a12a |

Anti-fibrotic and anti-proliferative |

[143] |

|

|

lincRNA 1700020I24Rik (ENSMUSG00000085438) |

DN mouse model Mesangial cells |

Binding to miR-34a-5p. Inhibition of Sirt1/ HIF-1α signal pathway by targeting miR-34a-5p. |

Anti-fibrotic |

[144] |

|

|

MEG3 |

RPTEC cells |

Anti-fibrotic |

[145] |

||

|

ZEB1-AS1 |

DN mouse model RPTEC cells |

Promoting Zeb1 expression by binding H3K4 Methyltransferase MLL1 |

Anti-fibrotic |

[146] |

|

|

ENST00000453774.1 |

Renal tissue of patients with renal fibrosis UUO mouse model RPTEC cells |

Anti-fibrotic |

[147] |

Note: Studies in bold are mechanistic studies. Abbreviations: UUO (ureteral unilateral obstruction); RPTEC (renal proximal tubular epithelial cells); DN (diabetic nephropathy)

5. New Therapeutic Targets and Innovative Biomarkers

5.1. New Therapeutic Targets

5.1.1. miRNAs as Therapeutic Targets

5.1.2. lncRNAs as Therapeutic Targets

6. Biomarkers

6.1. miRNAs

6.2. lncRNAs

References

- Jha, V.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Iseki, K.; Li, Z.; Naicker, S.; Plattner, B.; Saran, R.; Wang, A.Y.-M.; Yang, C.-W. Chronic kidney disease: Global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 2013, 382, 260–272.

- Klinkhammer, B.M.; Goldschmeding, R.; Floege, J.; Boor, P. Treatment of renal fibrosis—turning challenges into opportunities. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2017, 24, 117–129.

- Friedman, S.L.; Sheppard, D.; Duffield, J.S.; Violette, S. Therapy for fibrotic diseases: Nearing the starting line. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 167sr1.

- Pottier, N.; Cauffiez, C.; Perrais, M.; Barbry, P.; Mari, B. FibromiRs: Translating molecular discoveries into new anti-fibrotic drugs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 119–126.

- Gurtner, G.C.; Werner, S.; Barrandon, Y.; Longaker, M.T. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature 2008, 453, 314–321.

- Lu, P.; Takai, K.; Weaver, V.M.; Werb, Z. Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a005058.

- Levey, A.S.; Bosch, J.P.; Lewis, J.B.; Greene, T.; Rogers, N.; Roth, D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 130, 461–470.

- Berchtold, L.; Friedli, I.; Vallée, J.-P.; Moll, S.; Martin, P.-Y.; de Seigneux, S. Diagnosis and assessment of renal fibrosis: The state of the art. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2017, 147, w14442.

- Chung, A.C.-K.; Lan, H.Y. MicroRNAs in renal fibrosis. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 50.

- Van der Hauwaert, C.; Savary, G.; Hennino, M.-F.; Pottier, N.; Glowacki, F.; Cauffiez, C. Implication des microARN dans la fibrose rénale. Nephrol. Ther. 2015, 11, 474–482.

- Gomez, I.G.; Nakagawa, N.; Duffield, J.S. MicroRNAs as novel therapeutic targets to treat kidney injury and fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2016, 310, F931–F944.

- Moghaddas Sani, H.; Hejazian, M.; Hosseinian Khatibi, S.M.; Ardalan, M.; Zununi Vahed, S. Long non-coding RNAs: An essential emerging field in kidney pathogenesis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 99, 755–765.

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, F. Long noncoding RNA: A new contributor and potential therapeutic target in fibrosis. Epigenomics 2017, 9, 1233–1241.

- Cech, T.R.; Steitz, J.A. The noncoding RNA revolution—Trashing old rules to forge new ones. Cell 2014, 157, 77–94.

- Esteller, M. Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 861–874.

- Ulitsky, I.; Bartel, D.P. lincRNAs: Genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell 2013, 154, 26–46.

- Shi, X.; Sun, M.; Liu, H.; Yao, Y.; Song, Y. Long non-coding RNAs: A new frontier in the study of human diseases. Cancer Lett. 2013, 339, 159–166.

- Kozomara, A.; Birgaoanu, M.; Griffiths-Jones, S. miRBase: From microRNA sequences to function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D155–D162.

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 2009, 136, 215–233.

- Croce, C.M.; Calin, G.A. miRNAs, Cancer, and stem cell division. Cell 2005, 122, 6–7.

- Small, E.M.; Olson, E.N. Pervasive roles of microRNAs in cardiovascular biology. Nature 2011, 469, 336–342.

- Li, G.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, B.; Wu, Q.; Wang, C. Fibroproliferative effect of microRNA-21 in hypertrophic scar derived fibroblasts. Exp. Cell Res. 2016, 345, 93–99.

- Bowen, T.; Jenkins, R.H.; Fraser, D.J. MicroRNAs, transforming growth factor beta-1, and tissue fibrosis. J. Pathol. 2013, 229, 274–285.

- Corcoran, D.L.; Pandit, K.V.; Gordon, B.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Kaminski, N.; Benos, P.V. Features of mammalian microRNA promoters emerge from polymerase II chromatin immunoprecipitation data. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5279.

- Baskerville, S.; Bartel, D.P. Microarray profiling of microRNAs reveals frequent coexpression with neighboring miRNAs and host genes. RNA 2005, 11, 241–247.

- Ozsolak, F.; Poling, L.L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.S.; Roeder, R.G.; Zhang, X.; Song, J.S.; Fisher, D.E. Chromatin structure analyses identify miRNA promoters. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 3172–3183.

- Park, J.-E.; Heo, I.; Tian, Y.; Simanshu, D.K.; Chang, H.; Jee, D.; Patel, D.J.; Kim, V.N. Dicer recognizes the 5′ end of RNA for efficient and accurate processing. Nature 2011, 475, 201–205.

- Su, H.; Trombly, M.I.; Chen, J.; Wang, X. Essential and overlapping functions for mammalian Argonautes in microRNA silencing. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 304–317.

- Liu, X.; Jin, D.-Y.; McManus, M.T.; Mourelatos, Z. Precursor microRNA-programmed silencing complex assembly pathways in mammals. Mol. Cell 2012, 46, 507–517.

- Jonas, S.; Izaurralde, E. Towards a molecular understanding of microRNA-mediated gene silencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 421–433.

- Frankish, A.; Diekhans, M.; Ferreira, A.-M.; Johnson, R.; Jungreis, I.; Loveland, J.; Mudge, J.M.; Sisu, C.; Wright, J.; Armstrong, J.; et al. GENCODE reference annotation for the human and mouse genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D766–D773.

- Quinn, J.J.; Chang, H.Y. Unique features of long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 47–62.

- Bunch, H. Gene regulation of mammalian long non-coding RNA. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2018, 293, 1–15.

- Chen, L.-L. Linking long noncoding RNA localization and function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 761–772.

- Kung, J.T.Y.; Colognori, D.; Lee, J.T. Long noncoding RNAs: Past, present, and future. Genetics 2013, 193, 651–669.

- Derrien, T.; Johnson, R.; Bussotti, G.; Tanzer, A.; Djebali, S.; Tilgner, H.; Guernec, G.; Martin, D.; Merkel, A.; Knowles, D.G.; et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: Analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1775–1789.

- Devaux, Y.; Zangrando, J.; Schroen, B.; Creemers, E.E.; Pedrazzini, T.; Chang, C.-P.; Dorn, G.W.; Thum, T.; Heymans, S.; Cardiolinc Network. Long noncoding RNAs in cardiac development and ageing. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 415–425.

- Ward, M.; McEwan, C.; Mills, J.D.; Janitz, M. Conservation and tissue-specific transcription patterns of long noncoding RNAs. J. Hum. Transcript. 2015, 1, 2–9.

- Ulitsky, I. Evolution to the rescue: Using comparative genomics to understand long non-coding RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 601–614.

- Lv, W.; Fan, F.; Wang, Y.; Gonzalez-Fernandez, E.; Wang, C.; Yang, L.; Booz, G.W.; Roman, R.J. Therapeutic potential of microRNAs for the treatment of renal fibrosis and CKD. Physiol. Genomics 2018, 50, 20–34.

- Zarjou, A.; Yang, S.; Abraham, E.; Agarwal, A.; Liu, G. Identification of a microRNA signature in renal fibrosis: Role of miR-21. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2011, 301, F793–F801.

- Chau, B.N.; Xin, C.; Hartner, J.; Ren, S.; Castano, A.P.; Linn, G.; Li, J.; Tran, P.T.; Kaimal, V.; Huang, X.; et al. MicroRNA-21 promotes fibrosis of the kidney by silencing metabolic pathways. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, ra18–ra121.

- Dong, J.; Zhao, Y.-P.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, T.-P.; Chen, G. Bcl-2 upregulation induced by miR-21 Via a direct interaction is associated with apoptosis and chemoresistance in MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells. Arch. Med. Res. 2011, 42, 8–14.

- Zhou, J.; Wang, K.-C.; Wu, W.; Subramaniam, S.; Shyy, J.Y.-J.; Chiu, J.-J.; Li, J.Y.-S.; Chien, S. MicroRNA-21 targets peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor- in an autoregulatory loop to modulate flow-induced endothelial inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 10355–10360.

- Zhang, K.; Han, L.; Chen, L.; Shi, Z.; Yang, M.; Ren, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Pu, P.; Kang, C. Blockage of a miR-21/EGFR regulatory feedback loop augments anti-EGFR therapy in glioblastomas. Cancer Lett. 2014, 342, 139–149.

- Jiao, X.; Xu, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liang, M.; Teng, J.; Ding, X. miR-21 Contributes to renal protection by targeting prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in delayed ischaemic preconditioning. Nephrology 2017, 22, 366–373.

- Xu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, J.; Jia, W.; Ge, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X. MicroRNA-21 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cell proliferation through repression of mitogen-activated protein kinase-kinase 3. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 469.

- Li, Z.; Deng, X.; Kang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xia, T.; Ding, N.; Yin, Y. Elevation of miR-21, through targeting MKK3, may be involved in ischemia pretreatment protection from ischemia–reperfusion induced kidney injury. J. Nephrol. 2016, 29, 27–36.

- Zhou, L.; Yang, Z.-X.; Song, W.-J.; Li, Q.-J.; Yang, F.; Wang, D.-S.; Zhang, N.; Dou, K.-F. MicroRNA-21 regulates the migration and invasion of a stem-like population in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2013, 43, 661–669.

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Gao, C.; Chen, P.; Chen, J.; Liu, W.; Xiao, S.; Lu, H. miR-21 Plays a pivotal role in gastric cancer pathogenesis and progression. Lab. Investig. 2008, 88, 1358–1366.

- Wang, N.; Zhang, C.; He, J.; Duan, X.; Wang, Y.; Ji, X.; Zang, W.; Li, M.; Ma, Y.; Wang, T.; et al. miR-21 Down-regulation suppresses cell growth, invasion and induces cell apoptosis by targeting FASL, TIMP3, and RECK genes in esophageal carcinoma. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013, 58, 1863–1870.

- Hu, J.; Ni, S.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wu, T.; Yin, X.; Lang, Y.; Lu, H. The angiogenic effect of microRNA-21 targeting TIMP3 through the regulation of MMP2 and MMP9. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149537.

- Zhong, X.; Chung, A.C.K.; Chen, H.Y.; Dong, Y.; Meng, X.M.; Li, R.; Yang, W.; Hou, F.F.; Lan, H.Y. miR-21 Is a key therapeutic target for renal injury in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 663–674.

- Wang, J.-Y.; Gao, Y.-B.; Zhang, N.; Zou, D.-W.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Z.-Y.; Li, J.-Y.; Zhou, S.-N.; Wang, S.-C.; Wang, Y.-Y.; et al. miR-21 Overexpression enhances TGF-β1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by target smad7 and aggravates renal damage in diabetic nephropathy. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2014, 392, 163–172.

- Xu, X.; Song, N.; Zhang, X.; Jiao, X.; Hu, J.; Liang, M.; Teng, J.; Ding, X. Renal protection mediated by hypoxia inducible factor-1α depends on proangiogenesis function of miR-21 by targeting thrombospondin 1. Transplantation 2017, 101, 1811–1819.

- Liu, X.; Hong, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zou, X.; Xu, L. MiR-21 inhibits autophagy by targeting Rab11a in renal ischemia/reperfusion. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 338, 64–69.

- Lai, J.Y.; Luo, J.; O’Connor, C.; Jing, X.; Nair, V.; Ju, W.; Randolph, A.; Ben-Dov, I.Z.; Matar, R.N.; Briskin, D.; et al. MicroRNA-21 in glomerular injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 805–816.

- Glowacki, F.; Savary, G.; Gnemmi, V.; Buob, D.; Van der Hauwaert, C.; Lo-Guidice, J.-M.; Bouyé, S.; Hazzan, M.; Pottier, N.; Perrais, M.; et al. Increased circulating miR-21 levels are associated with kidney fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58014.

- Hennino, M.-F.; Buob, D.; Van der Hauwaert, C.; Gnemmi, V.; Jomaa, Z.; Pottier, N.; Savary, G.; Drumez, E.; Noël, C.; Cauffiez, C.; et al. miR-21-5p Renal expression is associated with fibrosis and renal survival in patients with IgA nephropathy. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27209.

- Guo, J.; Song, W.; Boulanger, J.; Xu, E.Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; He, Q.; Wang, S.; Yang, L.; Pryce, C.; et al. Dysregulated expression of microRNA-21 and disease related genes in human patients and mouse model of alport syndrome. Hum. Gene Ther. 2019.

- Dey, N.; Ghosh-Choudhury, N.; Kasinath, B.S.; Choudhury, G.G. TGFβ-stimulated microrna-21 utilizes PTEN to orchestrate AKT/mTORC1 signaling for mesangial cell hypertrophy and matrix expansion. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42316.

- Cheng, Y.; Zhu, P.; Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Dong, S.; Wang, X.; Chun, B.; Zhuang, J.; Zhang, C. Ischaemic preconditioning-regulated miR-21 protects heart against ischaemia/reperfusion injury via anti-apoptosis through its target PDCD4. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 87, 431–439.

- Sims, E.K.; Lakhter, A.J.; Anderson-Baucum, E.; Kono, T.; Tong, X.; Evans-Molina, C. MicroRNA 21 targets BCL2 mRNA to increase apoptosis in rat and human beta cells. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1057–1065.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wu, D.; Liu, X.; Shi, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Ding, J.; Xiao, Y.; Guo, B. MicroRNA-22 promotes renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis by targeting PTEN and suppressing autophagy in diabetic nephropathy. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 1–11.

- He, F.; Peng, F.; Xia, X.; Zhao, C.; Luo, Q.; Guan, W.; Li, Z.; Yu, X.; Huang, F. MiR-135a promotes renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy by regulating TRPC1. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1726–1736.

- Zhou, H.; Hasni, S.A.; Perez, P.; Tandon, M.; Jang, S.-I.; Zheng, C.; Kopp, J.B.; Austin, H.; Balow, J.E.; Alevizos, I.; et al. miR-150 Promotes renal fibrosis in lupus nephritis by downregulating SOCS1. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 1073–1087.

- Xi, W.; Zhao, X.; Wu, M.; Jia, W.; Li, H. Lack of microRNA-155 ameliorates renal fibrosis by targeting PDE3A/TGF-β1/Smad signaling in mice with obstructive nephropathy. Cell Biol. Int. 2018, 42, 1523–1532.

- XIE, S.; CHEN, H.; LI, F.; WANG, S.; GUO, J. Hypoxia-induced microRNA-155 promotes fibrosis in proximal tubule cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 4555–4560.

- Chen, B. The miRNA-184 drives renal fibrosis by targeting HIF1AN in vitro and in vivo. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2019, 51, 543–550.

- Bera, A.; Das, F.; Ghosh-Choudhury, N.; Mariappan, M.M.; Kasinath, B.S.; Ghosh Choudhury, G. Reciprocal regulation of miR-214 and PTEN by high glucose regulates renal glomerular mesangial and proximal tubular epithelial cell hypertrophy and matrix expansion. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2017, 313, C430–C447.

- Liu, M.; Liu, L.; Bai, M.; Zhang, L.; Ma, F.; Yang, X.; Sun, S. Hypoxia-induced activation of Twist/miR-214/E-cadherin axis promotes renal tubular epithelial cell mesenchymal transition and renal fibrosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 2324–2330.

- Zhu, X.; Li, W.; Li, H. miR-214 Ameliorates acute kidney injury via targeting DKK3 and activating of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Biol. Res. 2018, 51, 31.

- Mu, J.; Pang, Q.; Guo, Y.-H.; Chen, J.-G.; Zeng, W.; Huang, Y.-J.; Zhang, J.; Feng, B. Functional implications of MicroRNA-215 in TGF-β1-induced phenotypic transition of mesangial cells by targeting CTNNBIP1. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58622.

- Kato, M.; Wang, L.; Putta, S.; Wang, M.; Yuan, H.; Sun, G.; Lanting, L.; Todorov, I.; Rossi, J.J.; Natarajan, R. Post-transcriptional up-regulation of Tsc-22 by Ybx1, a target of miR-216a, mediates TGF-β-induced collagen expression in kidney cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 34004–34015.

- Macconi, D.; Tomasoni, S.; Romagnani, P.; Trionfini, P.; Sangalli, F.; Mazzinghi, B.; Rizzo, P.; Lazzeri, E.; Abbate, M.; Remuzzi, G.; et al. MicroRNA-324-3p promotes renal fibrosis and is a target of ACE inhibition. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 23, 1496–1505.

- Li, R.; Chung, A.C.K.; Dong, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhong, X.; Lan, H.Y. The microRNA miR-433 promotes renal fibrosis by amplifying the TGF-β/Smad3-Azin1 pathway. Kidney Int. 2013, 84, 1129–1144.

- Alvarez, M.L.; Khosroheidari, M.; Eddy, E.; Kiefer, J. Role of MicroRNA 1207-5P and its host gene, the long non-coding RNA Pvt1, as mediators of extracellular matrix accumulation in the kidney: Implications for diabetic nephropathy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77468.

- Brennan, E.P.; Nolan, K.A.; Börgeson, E.; Gough, O.S.; McEvoy, C.M.; Docherty, N.G.; Higgins, D.F.; Murphy, M.; Sadlier, D.M.; Ali-Shah, S.T.; et al. Lipoxins attenuate renal fibrosis by inducing let-7c and suppressing TGF β R1. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 627–637.

- Wang, B.; Jha, J.C.; Hagiwara, S.; McClelland, A.D.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K.; Thomas, M.C.; Cooper, M.E.; Kantharidis, P. Transforming growth factor-β1-mediated renal fibrosis is dependent on the regulation of transforming growth factor receptor 1 expression by let-7b. Kidney Int. 2014, 85, 352–361.

- Cushing, L.; Kuang, P.; Lü, J. The role of miR-29 in pulmonary fibrosis. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2015, 93, 109–118.

- Meng, X.-M.; Tang, P.M.-K.; Li, J.; Lan, H.Y. TGF-Î2/Smad signaling in renal fibrosis. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 82.

- Van Rooij, E.; Sutherland, L.B.; Thatcher, J.E.; DiMaio, J.M.; Naseem, R.H.; Marshall, W.S.; Hill, J.A.; Olson, E.N. Dysregulation of microRNAs after myocardial infarction reveals a role of miR-29 in cardiac fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13027–13032.

- Qin, W.; Chung, A.C.K.; Huang, X.R.; Meng, X.-M.; Hui, D.S.C.; Yu, C.-M.; Sung, J.J.Y.; Lan, H.Y. TGF-β/Smad3 signaling promotes renal fibrosis by inhibiting miR-29. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 22, 1462–1474.

- Ramdas, V.; McBride, M.; Denby, L.; Baker, A.H. Canonical transforming growth factor-β signaling regulates disintegrin metalloprotease expression in experimental renal fibrosis via miR-29. Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 183, 1885–1896.

- Wang, B.; Komers, R.; Carew, R.; Winbanks, C.E.; Xu, B.; Herman-Edelstein, M.; Koh, P.; Thomas, M.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K.; Gregorevic, P.; et al. Suppression of microRNA-29 expression by TGF-β1 promotes collagen expression and renal fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 23, 252–265.

- Hu, H.; Hu, S.; Xu, S.; Gao, Y.; Zeng, F.; Shui, H. miR-29b Regulates Ang II-induced EMT of rat renal tubular epithelial cells via targeting PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 453–460.

- Long, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Chang, B.H.J.; Danesh, F.R. MicroRNA-29c is a signature microrna under high glucose conditions that targets sprouty homolog 1, and its in vivo knockdown prevents progression of diabetic nephropathy. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 11837–11848.

- Hennemeier, I.; Humpf, H.-U.; Gekle, M.; Schwerdt, G. Role of microRNA-29b in the ochratoxin a-induced enhanced collagen formation in human kidney cells. Toxicology 2014, 324, 116–122.

- Ben-Dov, I.Z.; Muthukumar, T.; Morozov, P.; Mueller, F.B.; Tuschl, T.; Suthanthiran, M. MicroRNA sequence profiles of human kidney allografts with or without tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Transplantation 2012, 94, 1086–1094.

- Jiang, L.; Qiu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Wen, P.; Fang, L.; Cao, H.; Zen, K.; He, W.; Zhang, C.; Dai, C.; et al. A microRNA-30e/mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 axis mediates TGF-β1-induced tubular epithelial cell extracellular matrix production and kidney fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2013, 84, 285–296.

- Wang, J.; Duan, L.; Guo, T.; Gao, Y.; Tian, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, J. Downregulation of miR-30c promotes renal fibrosis by target CTGF in diabetic nephropathy. J. Diabetes Complications 2016, 30, 406–414.

- Morizane, R.; Fujii, S.; Monkawa, T.; Hiratsuka, K.; Yamaguchi, S.; Homma, K.; Itoh, H. miR-34c Attenuates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and kidney fibrosis with ureteral obstruction. Sci. Rep. 2015, 4, 4578.

- Ning, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Zeng, R.; Wang, G. miR-152 Regulates TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition by targeting HPIP in tubular epithelial cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 7973–7979.

- Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Heng, Y.; Miao, C. MicroRNA-181 exerts an inhibitory role during renal fibrosis by targeting early growth response factor-1 and attenuating the expression of profibrotic markers. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019.

- Shen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, C.; Yin, A. MicroRNA-194 overexpression protects against hypoxia/reperfusion-induced HK-2 cell injury through direct targeting Rheb. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 8311–8318.

- Liu, F.; Zhang, Z.-P.; Xin, G.-D.; Guo, L.-H.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Z.-X. miR-192 Prevents renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy by targeting Egr1. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 4252–4260.

- Wang, B.; Koh, P.; Winbanks, C.; Coughlan, M.T.; McClelland, A.; Watson, A.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K.; Burns, W.C.; Thomas, M.C.; Cooper, M.E.; et al. miR-200a Prevents renal fibrogenesis through repression of TGF-β2 expression. Diabetes 2011, 60, 280–287.

- Oba, S.; Kumano, S.; Suzuki, E.; Nishimatsu, H.; Takahashi, M.; Takamori, H.; Kasuya, M.; Ogawa, Y.; Sato, K.; Kimura, K.; et al. miR-200b Precursor can ameliorate renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13614.

- Howe, E.N.; Cochrane, D.R.; Richer, J.K. The miR-200 and miR-221/222 microRNA families: Opposing effects on epithelial identity. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2012, 17, 65–77.

- Bai, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, X.; Cui, H.; Hao, J.; Han, J.; Cao, N. Erythropoietin inhibits hypoxia–induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via upregulation of miR-200b in HK-2 cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 42, 269–280.

- Xiong, M.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Qiu, W.; Fang, L.; Tan, R.; Wen, P.; Yang, J. The miR-200 family regulates TGF-β1-induced renal tubular epithelial to mesenchymal transition through Smad pathway by targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2 expression. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2012, 302, F369–F379.

- Tang, O.; Chen, X.-M.; Shen, S.; Hahn, M.; Pollock, C.A. MiRNA-200b represses transforming growth factor-β1-induced EMT and fibronectin expression in kidney proximal tubular cells. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2013, 304, F1266–F1273.

- Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Ding, Y.; Zhu, M.; Lu, K.; Zhou, J.; Xie, X.; Xu, Y.; Shen, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. MiR-455-3p suppresses renal fibrosis through repression of ROCK2 expression in diabetic nephropathy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 977–983.

- Putta, S.; Lanting, L.; Sun, G.; Lawson, G.; Kato, M.; Natarajan, R. Inhibiting MicroRNA-192 ameliorates renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 23, 458–469.

- Kato, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Lanting, L.; Yuan, H.; Rossi, J.J.; Natarajan, R. MicroRNA-192 in diabetic kidney glomeruli and its function in TGF-beta-induced collagen expression via inhibition of E-box repressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 3432–3437.

- Chung, A.C.K.; Huang, X.R.; Meng, X.; Lan, H.Y. miR-192 Mediates TGF-β/Smad3-driven renal fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 1317–1325.

- Chung, A.C.K.; Dong, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhong, X.; Li, R.; Lan, H.Y. Smad7 suppresses renal fibrosis via altering expression of TGF-β/Smad3-regulated microRNAs. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 388–398.

- Krupa, A.; Jenkins, R.; Luo, D.D.; Lewis, A.; Phillips, A.; Fraser, D. Loss of MicroRNA-192 promotes fibrogenesis in diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 438–447.

- Wang, B.; Herman-Edelstein, M.; Koh, P.; Burns, W.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K.; Watson, A.; Saleem, M.; Goodall, G.J.; Twigg, S.M.; Cooper, M.E.; et al. E-cadherin expression is regulated by miR-192/215 by a mechanism that is independent of the profibrotic effects of transforming growth factor-beta. Diabetes 2010, 59, 1794–1802.

- Huang, S.; Zhang, L.; Song, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, X.; Guo, Z.; Chen, F.; Zhao, X. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 mediates cardiac fibrosis in experimental postinfarct myocardium mice model. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 2997–3006.

- Yu, F.; Lu, Z.; Cai, J.; Huang, K.; Chen, B.; Li, G.; Dong, P.; Zheng, J. MALAT1 functions as a competing endogenous RNA to mediate Rac1 expression by sequestering miR-101b in liver fibrosis. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 3885–3896.

- Zhang, K.; Han, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, L.; Hu, Z.; Yao, Q.; Cui, H.; Shu, G.; Si, M.; Li, C.; et al. The liver-enriched lnc-LFAR1 promotes liver fibrosis by activating TGFβ and Notch pathways. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 144.

- Zhang, Q.-Q.; Xu, M.-Y.; Qu, Y.; Hu, J.-J.; Li, Z.-H.; Zhang, Q.-D.; Lu, L.-G. TET3 mediates the activation of human hepatic stellate cells via modulating the expression of long non-coding RNA HIF1A-AS1. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 7744–7751.

- Lu, Q.; Guo, Z.; Xie, W.; Jin, W.; Zhu, D.; Chen, S.; Ren, T. The lncRNA H19 mediates pulmonary fibrosis by regulating the miR-196a/COL1A1 axis. Inflammation 2018, 41, 896–903.

- Savary, G.; Dewaeles, E.; Diazzi, S.; Buscot, M.; Nottet, N.; Fassy, J.; Courcot, E.; Henaoui, I.-S.; Lemaire, J.; Martis, N.; et al. The long non-coding RNA DNM3OS is a reservoir of fibromirs with major functions in lung fibroblast response to TGF-β and pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019.

- Sandy Fellah; Romain Larrue; Marin Truchi; Georges Vassaux; Bernard Mari; Christelle Cauffiez; Nicolas Pottier; Pervasive role of the long noncoding RNA DNM3OS in development and diseases. WIREs RNA 2022, e1736, e1736, 10.1002/wrna.1736.

- Grégoire Savary; Edmone Dewaeles; Serena Diazzi; Matthieu Buscot; Nicolas Nottet; Julien Fassy; Elisabeth Courcot; Imène-Sarah Henaoui; Julie Lemaire; Nihal Martis; et al.Cynthia Van Der HauwaertNicolas PonsVirginie MagnoneSylvie LeroyVéronique HofmanLaurent PlantierKevin LebrigandAgnès PaquetChristian Lino CardenasGeorges VassauxPaul HofmanAndreas GüntherBruno CrestaniBenoit WallaertRoger RezzonicoThierry BrousseauFrançois GlowackiSaverio BellusciMichael PerraisFranck BrolyPascal BarbryCharles-Hugo MarquetteChristelle CauffiezBernard MariNicolas Pottier The Long Noncoding RNA DNM3OS Is a Reservoir of FibromiRs with Major Functions in Lung Fibroblast Response to TGF-β and Pulmonary Fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2019, 200, 184-198, 10.1164/rccm.201807-1237oc.

- Han, R.; Hu, S.; Qin, W.; Shi, J.; Zeng, C.; Bao, H.; Liu, Z. Upregulated long noncoding RNA LOC105375913 induces tubulointerstitial fibrosis in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 716.

- Chen, W.; Zhou, Z.-Q.; Ren, Y.-Q.; Zhang, L.; Sun, L.-N.; Man, Y.-L.; Wang, Z.-K. Effects of long non-coding RNA LINC00667 on renal tubular epithelial cell proliferation, apoptosis and renal fibrosis via the miR-19b-3p/LINC00667/CTGF signaling pathway in chronic renal failure. Cell. Signal. 2019, 54, 102–114.

- Huang, S.; Xu, Y.; Ge, X.; Xu, B.; Peng, W.; Jiang, X.; Shen, L.; Xia, L. Long noncoding RNA NEAT1 accelerates the proliferation and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy through activating Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 11200–11207.

- Wang, P.; Luo, M.-L.; Song, E.; Zhou, Z.; Ma, T.; Wang, J.; Jia, N.; Wang, G.; Nie, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. Long noncoding RNA lnc-TSI inhibits renal fibrogenesis by negatively regulating the TGF-β/Smad3 pathway. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaat2039.

- Liang, Y.-J.; Wang, Q.-Y.; Zhou, C.-X.; Yin, Q.-Q.; He, M.; Yu, X.-T.; Cao, D.-X.; Chen, G.-Q.; He, J.-R.; Zhao, Q. MiR-124 targets Slug to regulate epithelial–mesenchymal transition and metastasis of breast cancer. Carcinogenesis 2013, 34, 713–722.

- Jiang, L.; Lin, T.; Xu, C.; Hu, S.; Pan, Y.; Jin, R. miR-124 Interacts with the Notch1 signalling pathway and has therapeutic potential against gastric cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2016, 20, 313–322.

- Chen, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Z.-Q.; Ren, Y.-Q.; Sun, L.-N.; Man, Y.-L.; Ma, Z.-W.; Wang, Z.-K. Effects of long non-coding RNA LINC00963 on renal interstitial fibrosis and oxidative stress of rats with chronic renal failure via the foxo signaling pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 46, 815–828.

- Zhou, S.-G.; Zhang, W.; Ma, H.-J.; Guo, Z.-Y.; Xu, Y. Silencing of LncRNA TCONS_00088786 reduces renal fibrosis through miR-132. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 166–173.

- Zhou, Q.; Chung, A.C.K.; Huang, X.R.; Dong, Y.; Yu, X.; Lan, H.Y. Identification of novel long noncoding RNAs associated with TGF-β/Smad3-mediated renal inflammation and fibrosis by RNA sequencing. Am. J. Pathol. 2014, 184, 409–417.

- Feng, M.; Tang, P.M.-K.; Huang, X.-R.; Sun, S.-F.; You, Y.-K.; Xiao, J.; Lv, L.-L.; Xu, A.-P.; Lan, H.-Y. TGF-β mediates renal fibrosis via the Smad3-Erbb4-IR long noncoding RNA axis. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 148–161.

- Sun, S.F.; Tang, P.M.K.; Feng, M.; Xiao, J.; Huang, X.R.; Li, P.; Ma, R.C.W.; Lan, H.Y. Novel lncRNA Erbb4-IR promotes diabetic kidney injury in db/db mice by targeting miR-29b. Diabetes 2018, 67, 731–744.

- Zhang, C.; Yuan, J.; Hu, H.; Chen, W.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Sun, S.; Guo, Z. Long non-coding RNA CHCHD4P4 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and inhibits cell proliferation in calcium oxalate-induced kidney damage. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2017, 51, e6536.

- Sun, J.; Zhang, S.; Shi, B.; Zheng, D.; Shi, J. Transcriptome identified lncRNAs associated with renal fibrosis in UUO rat model. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 658.

- Gao, Y.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, J.-X.; Li, Y.-K. Long non-coding RNA ASncmtRNA-2 is upregulated in diabetic kidneys and high glucose-treated mesangial cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 13, 581–587.

- Zhang, H.; Sun, S.-C. NF-κB in inflammation and renal diseases. Cell Biosci. 2015, 5, 63.

- Yi, H.; Peng, R.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Y.; Peng, H.; Liu, H.; Yu, L.; Li, A.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, W.; et al. LincRNA-Gm4419 knockdown ameliorates NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2583.

- Xie, H.; Xue, J.-D.; Chao, F.; Jin, Y.-F.; Fu, Q.; Xie, H.; Xue, J.-D.; Chao, F.; Jin, Y.-F.; Fu, Q. Long non-coding RNA-H19 antagonism protects against renal fibrosis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 51473–51481.

- Arvaniti, E.; Moulos, P.; Vakrakou, A.; Chatziantoniou, C.; Chadjichristos, C.; Kavvadas, P.; Charonis, A.; Politis, P.K. Whole-transcriptome analysis of UUO mouse model of renal fibrosis reveals new molecular players in kidney diseases. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26235.

- Zhou, Q.; Huang, X.R.; Yu, J.; Yu, X.; Lan, H.Y. Long noncoding RNA Arid2-IR is a novel therapeutic target for renal inflammation. Mol. Ther. 2015, 23, 1034–1043.

- Gao, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, F.; Guo, C. LncRNA-NR_033515 promotes proliferation, fibrogenesis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by targeting miR-743b-5p in diabetic nephropathy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 543–552.

- Hu, M.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Fan, M.; Lin, J.; Zhen, J.; Chen, L.; Lv, Z. LncRNA MALAT1 is dysregulated in diabetic nephropathy and involved in high glucose-induced podocyte injury via its interplay with β-catenin. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 2732–2747.

- Feng, Y.; Chen, S.; Xu, J.; Zhu, Q.; Ye, X.; Ding, D.; Yao, W.; Lu, Y.; Ye, X.; Ye, X.; et al. Dysregulation of lncRNAs GM5524 and GM15645 involved in high-glucose-induced podocyte apoptosis and autophagy in diabetic nephropathy. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 3657–3664.

- Polovic, M.; Dittmar, S.; Hennemeier, I.; Humpf, H.-U.; Seliger, B.; Fornara, P.; Theil, G.; Azinovic, P.; Nolze, A.; Köhn, M.; et al. Identification of a novel lncRNA induced by the nephrotoxin ochratoxin A and expressed in human renal tumor tissue. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 2241–2256.

- Wang, M.; Wang, S.; Yao, D.; Yan, Q.; Lu, W. A novel long non-coding RNA CYP4B1-PS1-001 regulates proliferation and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2016, 426, 136–145.

- Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Yao, D.; Chen, T.; Yan, Q.; Lu, W. Long non-coding RNA CYP4B1-PS1-001 inhibits proliferation and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy by interacting with Nucleolin. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 49, 2174–2187.

- Wang, M.; Yao, D.; Wang, S.; Yan, Q.; Lu, W. Long non-coding RNA ENSMUST00000147869 protects mesangial cells from proliferation and fibrosis induced by diabetic nephropathy. Endocrine 2016, 54, 81–92.

- Li, A.; Peng, R.; Sun, Y.; Liu, H.; Peng, H.; Zhang, Z. LincRNA 1700020I14Rik alleviates cell proliferation and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy via miR-34a-5p/Sirt1/HIF-1α signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 461.

- Xue, R.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; An, C.; Ma, Z. miR-185 Affected the EMT, cell viability and proliferation via DNMT1/MEG3 pathway in TGF-β1-induced renal fibrosis. Cell Biol. Int. 2018.

- Wang, J.; Pang, J.; Li, H.; Long, J.; Fang, F.; Chen, J.; Zhu, X.; Xiang, X.; Zhang, D. lncRNA ZEB1-AS1 was suppressed by p53 for renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 12, 741–750.

- Xiao, X.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Z.; Fang, X.; Zhang, H.; Peng, L.; Xiao, P. LncRNA ENST00000453774.1 contributes to oxidative stress defense dependent on autophagy mediation to reduce extracellular matrix and alleviate renal fibrosis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 234, 9130–9143.

- Van Rooij, E.; Kauppinen, S. Development of microRNA therapeutics is coming of age. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 851–864.

- Chiu, Y.-L.; Rana, T.M. siRNA function in RNAi: A chemical modification analysis. RNA 2003, 9, 1034–1048.

- Chen, P.Y.; Weinmann, L.; Gaidatzis, D.; Pei, Y.; Zavolan, M.; Tuschl, T.; Meister, G. Strand-specific 5′-O-methylation of siRNA duplexes controls guide strand selection and targeting specificity. RNA 2008, 14, 263–274.

- Michelfelder, S.; Trepel, M. Adeno-associated viral vectors and their redirection to cell-type specific receptors. Adv. Genet. 2009, 67, 29–60.

- Montgomery, R.L.; Yu, G.; Latimer, P.A.; Stack, C.; Robinson, K.; Dalby, C.M.; Kaminski, N.; van Rooij, E. MicroRNA mimicry blocks pulmonary fibrosis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 1347–1356.

- Chakraborty, C.; Sharma, A.R.; Sharma, G.; Doss, C.G.P.; Lee, S.-S. Therapeutic miRNA and siRNA: Moving from bench to clinic as next generation medicine. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2017, 8, 132–143.

- Lennox, K.A.; Behlke, M.A. Chemical modification and design of anti-miRNA oligonucleotides. Gene Ther. 2011, 18, 1111–1120.

- Louloupi, A.; Ørom, U.A.V. Inhibiting pri-miRNA processing with target site blockers. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1823, 63–68.

- Knauss, J.L.; Bian, S.; Sun, T. Plasmid-based target protectors allow specific blockade of miRNA silencing activity in mammalian developmental systems. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 163.

- Denby, L.; Ramdas, V.; Lu, R.; Conway, B.R.; Grant, J.S.; Dickinson, B.; Aurora, A.B.; McClure, J.D.; Kipgen, D.; Delles, C.; et al. MicroRNA-214 antagonism protects against renal fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 65–80.

- Kölling, M.; Kaucsar, T.; Schauerte, C.; Hübner, A.; Dettling, A.; Park, J.-K.; Busch, M.; Wulff, X.; Meier, M.; Scherf, K.; et al. Therapeutic miR-21 silencing ameliorates diabetic kidney disease in mice. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 165–180.

- Gomez, I.G.; MacKenna, D.A.; Johnson, B.G.; Kaimal, V.; Roach, A.M.; Ren, S.; Nakagawa, N.; Xin, C.; Newitt, R.; Pandya, S.; et al. Anti–microRNA-21 oligonucleotides prevent Alport nephropathy progression by stimulating metabolic pathways. J. Clin. Invest. 2015, 125, 141–156.

- Creemers, E.E.; van Rooij, E. Function and therapeutic potential of noncoding RNAs in cardiac fibrosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 108–118.

- Bonetti, A.; Carninci, P. From bench to bedside: The long journey of long non-coding RNAs. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 2017, 3, 119–124.

- Hagedorn, P.H.; Pontoppidan, M.; Bisgaard, T.S.; Berrera, M.; Dieckmann, A.; Ebeling, M.; Møller, M.R.; Hudlebusch, H.; Jensen, M.L.; Hansen, H.F.; et al. Identifying and avoiding off-target effects of RNase H-dependent antisense oligonucleotides in mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 5366–5380.

- Kato, M.; Wang, M.; Chen, Z.; Bhatt, K.; Oh, H.J.; Lanting, L.; Deshpande, S.; Jia, Y.; Lai, J.Y.C.; O’Connor, C.L.; et al. An endoplasmic reticulum stress-regulated lncRNA hosting a microRNA megacluster induces early features of diabetic nephropathy. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12864.

- Li, C.H.; Chen, Y. Targeting long non-coding RNAs in cancers: Progress and prospects. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 45, 1895–1910.

- Prasad, N.; Kumar, S.; Manjunath, R.; Bhadauria, D.; Kaul, A.; Sharma, R.K.; Gupta, A.; Lal, H.; Jain, M.; Agrawal, V. Real-time ultrasound-guided percutaneous renal biopsy with needle guide by nephrologists decreases post-biopsy complications. Clin. Kidney J. 2015, 8, 151–156.

- Schwab, S.; Marwitz, T.; Woitas, R.P. The role of prognostic assessment with biomarkers in chronic kidney disease: A narrative review. J. Lab. Precis. Med. 2018, 3, 12.

- Weber, J.A.; Baxter, D.H.; Zhang, S.; Huang, D.Y.; How Huang, K.; Jen Lee, M.; Galas, D.J.; Wang, K. The microRNA spectrum in 12 body fluids. Clin. Chem. 2010, 56, 1733–1741.

- Mitchell, P.S.; Parkin, R.K.; Kroh, E.M.; Fritz, B.R.; Wyman, S.K.; Pogosova-Agadjanyan, E.L.; Peterson, A.; Noteboom, J.; O’Briant, K.C.; Allen, A.; et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 10513–10518.

- Bolha, L.; Ravnik-Glavač, M.; Glavač, D. Long noncoding RNAs as biomarkers in cancer. Dis. Markers 2017, 2017, 7243968.

- Cheng, L.; Sun, X.; Scicluna, B.J.; Coleman, B.M.; Hill, A.F. Characterization and deep sequencing analysis of exosomal and non-exosomal miRNA in human urine. Kidney Int. 2014, 86, 433–444.

- Cardenas-Gonzalez, M.; Srivastava, A.; Pavkovic, M.; Bijol, V.; Rennke, H.G.; Stillman, I.E.; Zhang, X.; Parikh, S.; Rovin, B.H.; Afkarian, M.; et al. Identification, confirmation, and replication of novel urinary microRNA biomarkers in lupus nephritis and diabetic nephropathy. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63, 1515–1526.

- Ramachandran, K.; Saikumar, J.; Bijol, V.; Koyner, J.L.; Qian, J.; Betensky, R.A.; Waikar, S.S.; Vaidya, V.S. Human miRNome profiling identifies microRNAs differentially present in the urine after kidney injury. Clin. Chem. 2013, 59, 1742–1752.

- Sonoda, H.; Lee, B.R.; Park, K.-H.; Nihalani, D.; Yoon, J.-H.; Ikeda, M.; Kwon, S.-H. miRNA Profiling of urinary exosomes to assess the progression of acute kidney injury. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4692.

- Khurana, R.; Ranches, G.; Schafferer, S.; Lukasser, M.; Rudnicki, M.; Mayer, G.; Hüttenhofer, A. Identification of urinary exosomal noncoding RNAs as novel biomarkers in chronic kidney disease. RNA 2017, 23, 142–152.

- Chen, C.; Lu, C.; Qian, Y.; Li, H.; Tan, Y.; Cai, L.; Weng, H. Urinary miR-21 as a potential biomarker of hypertensive kidney injury and fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17737.

- Lv, L.-L.; Cao, Y.-H.; Ni, H.-F.; Xu, M.; Liu, D.; Liu, H.; Chen, P.-S.; Liu, B.-C. MicroRNA-29c in urinary exosome/microvesicle as a biomarker of renal fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2013, 305, F1220–F1227.

- Zununi Vahed, S.; Omidi, Y.; Ardalan, M.; Samadi, N. Dysregulation of urinary miR-21 and miR-200b associated with interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA) in renal transplant recipients. Clin. Biochem. 2017, 50, 32–39.

- Zhou, H.; Cheruvanky, A.; Hu, X.; Matsumoto, T.; Hiramatsu, N.; Cho, M.E.; Berger, A.; Leelahavanichkul, A.; Doi, K.; Chawla, L.S.; et al. Urinary exosomal transcription factors, a new class of biomarkers for renal disease. Kidney Int. 2008, 74, 613–621.

- Zununi Vahed, S.; Poursadegh Zonouzi, A.; Ghanbarian, H.; Ghojazadeh, M.; Samadi, N.; Ardalan, M. Upregulated expression of circulating microRNAs in kidney transplant recipients with interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. Iran. J. Kidney Dis. 2017, 11, 309–318.

- Muralidharan, J.; Ramezani, A.; Hubal, M.; Knoblach, S.; Shrivastav, S.; Karandish, S.; Scott, R.; Maxwell, N.; Ozturk, S.; Beddhu, S.; et al. Extracellular microRNA signature in chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2017, 312, F982–F991.

- Poel, D.; Buffart, T.E.; Oosterling-Jansen, J.; Verheul, H.M.; Voortman, J. Evaluation of several methodological challenges in circulating miRNA qPCR studies in patients with head and neck cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, e454.

- Nair, V.S.; Pritchard, C.C.; Tewari, M.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Design and analysis for studying microRNAs in human disease: A primer on -omic technologies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 180, 140–152.

- Haider, B.A.; Baras, A.S.; McCall, M.N.; Hertel, J.A.; Cornish, T.C.; Halushka, M.K. A critical evaluation of microRNA biomarkers in non-neoplastic disease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89565.

- Ma, J.; Li, N.; Guarnera, M.; Jiang, F. Quantification of plasma miRNAs by digital PCR for cancer diagnosis. Biomark. Insights 2013, 8, 127–136.

- Hindson, C.M.; Chevillet, J.R.; Briggs, H.A.; Gallichotte, E.N.; Ruf, I.K.; Hindson, B.J.; Vessella, R.L.; Tewari, M. Absolute quantification by droplet digital PCR versus analog real-time PCR. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 1003–1005.

- Mohankumar, S.; Patel, T. Extracellular vesicle long noncoding RNA as potential biomarkers of liver cancer. Brief. Funct. Genomics 2016, 15, 249–256.