| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pei Pei Pan | -- | 2956 | 2022-09-29 03:35:27 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 2956 | 2022-09-29 06:08:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

Growth hormone (GH) has been used as a co-gonadotrophin in assisted reproduction, particularly in poor ovarian responders. The application of GH has been alleged to activate primordial follicles and improve oocyte quality, embryo quality, and steroidogenesis. However, the effects of GH on the live birth rate among women is controversial. Additionally, although the basic biological mechanisms that lead to the above clinical differences have been investigated, they are not yet well understood. The actions of GH are mediated by GH receptors (GHRs) or insulin-like growth factors (IGFs). GH regulates the vital signal transduction pathways that are involved in primordial follicular activation, steroidogenesis, and oocyte maturation.

1. Introduction

2. Molecular Mechanisms of Growth Hormone in Ovarian Functions

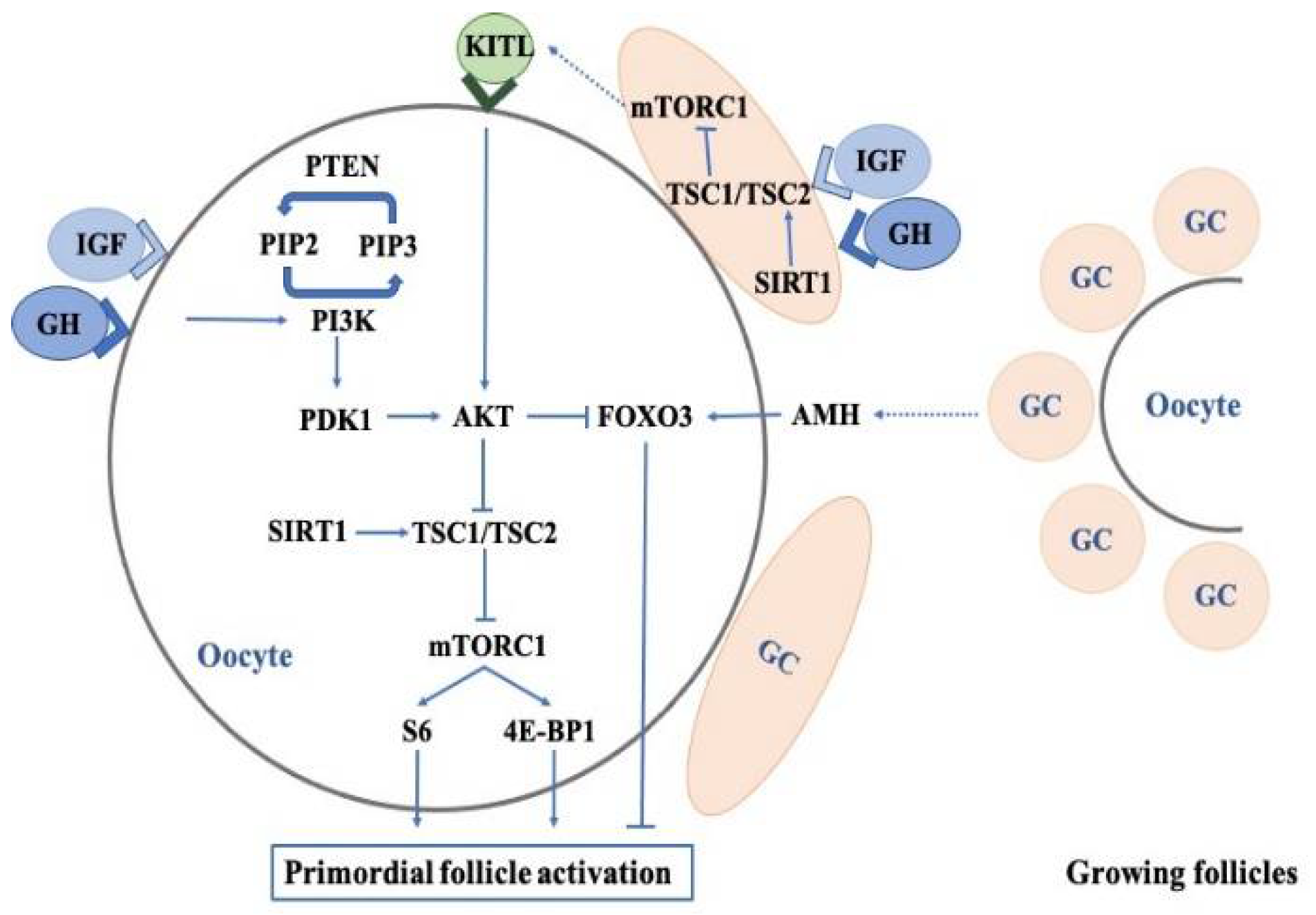

2.1. Effects of Growth Hormone on the Regulation of Primordial Follicles

2.2. Effects of Growth Hormone on Oocyte Quality

2.3. Effects of Growth Hormone on the Sensitivity of Oocytes to Gonadotropins

2.4. Effects of Growth Hormone on Granulosa Cells and Thecal Cells

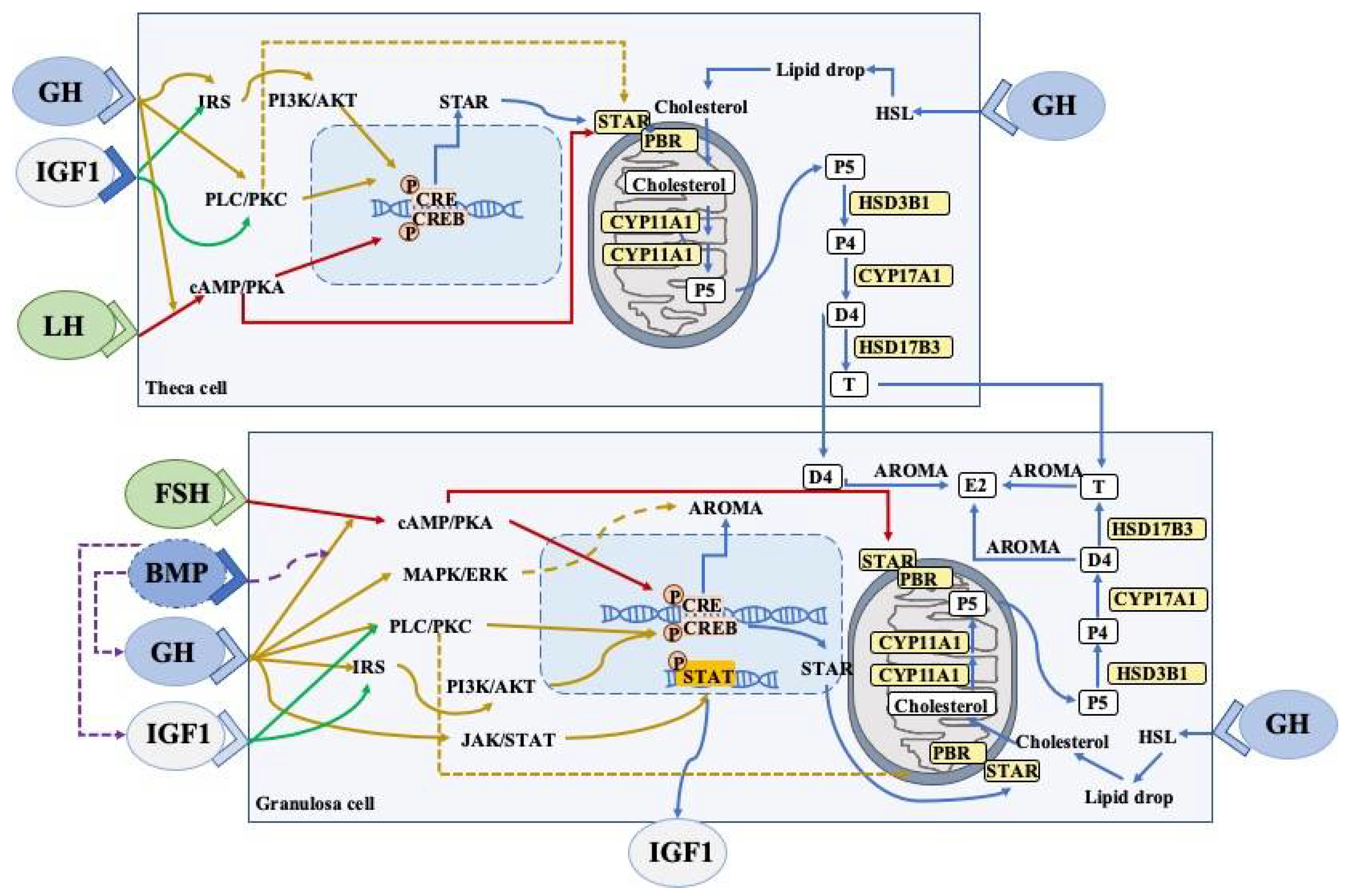

2.4.1. Steroidogenesis

2.4.2. JAK2-Dependent Signaling Pathway

2.4.3. JAK2-Independent Signaling Pathway

2.4.4. FSHR Pathway

2.4.5. GH/IGFs Signaling Pathway

2.5. Mitochondrial Functions

References

- Dosouto, C.; Calaf, J.; Polo, A.; Haahr, T.; Humaidan, P. Growth Hormone and Reproduction: Lessons Learned From Animal Models and Clinical Trials. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 404.

- Kolibianakis, E.M.; Venetis, C.A.; Diedrich, K.; Tarlatzis, B.C.; Griesinger, G. Addition of growth hormone to gonadotrophins in ovarian stimulation of poor responders treated by in-vitro fertilization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2009, 15, 613–622.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Shu, J.; Guo, J.; Chang, H.-M.; Leung, P.C.K.; Sheng, J.-Z.; Huang, H. Adjuvant treatment strategies in ovarian stimulation for poor responders undergoing IVF: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2020, 26, 247–263.

- Bachelot, A.; Monget, P.; Imbert-Bolloré, P.; Coshigano, K.; Kopchick, J.J.; Kelly, P.A.; Binart, N. Growth hormone is required for ovarian follicular growth. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 4104–4112.

- Banerjee, S.; Chaturvedi, C.M. Specific neural phase relation of serotonin and dopamine modulate the testicular activity in Japanese quail. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 2866–2879.

- Devesa, J.; Caicedo, D. The Role of Growth Hormone on Ovarian Functioning and Ovarian Angiogenesis. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 450.

- Kajimura, S.; Kawaguchi, N.; Kaneko, T.; Kawazoe, I.; Hirano, T.; Visitacion, N.; Grau, E.G.; Aida, K. Identification of the growth hormone receptor in an advanced teleost, the tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) with special reference to its distinct expression pattern in the ovary. J. Endocrinol. 2004, 181, 65–76.

- Ahumada-Solórzano, S.M.; Carranza, M.E.; Pedernera, E.; Rodríguez-Méndez, A.J.; Luna, M.; Arámburo, C. Local expression and distribution of growth hormone and growth hormone receptor in the chicken ovary: Effects of GH on steroidogenesis in cultured follicular granulosa cells. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2012, 175, 297–310.

- Zhao, J.; Taverne, M.A.M.; van der Weijden, G.C.; Bevers, M.M.; van den Hurk, R. Immunohistochemical localisation of growth hormone (GH), GH receptor (GHR), insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and type I IGF-I receptor, and gene expression of GH and GHR in rat pre-antral follicles. Zygote 2002, 10, 85–94.

- Steffl, M.; Schweiger, M.; Mayer, J.; Amselgruber, W.M. Expression and localization of growth hormone receptor in the oviduct of cyclic and pregnant pigs and mid-implantation conceptuses. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 131, 773–779.

- Marchal, R.; Caillaud, M.; Martoriati, A.; Gérard, N.; Mermillod, P.; Goudet, G. Effect of growth hormone (GH) on in vitro nuclear and cytoplasmic oocyte maturation, cumulus expansion, hyaluronan synthases, and connexins 32 and 43 expression, and GH receptor messenger RNA expression in equine and porcine species. Biol. Reprod. 2003, 69, 1013–1022.

- de Prada, J.K.N.; VandeVoort, C.A. Growth hormone and in vitro maturation of rhesus macaque oocytes and subsequent embryo development. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2008, 25, 145–158.

- Abir, R.; Garor, R.; Felz, C.; Nitke, S.; Krissi, H.; Fisch, B. Growth hormone and its receptor in human ovaries from fetuses and adults. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 90, 1333–1339.

- Xu, Y.-M.; Hao, G.-M.; Gao, B.-L. Application of Growth Hormone in in vitro Fertilization. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 502.

- Hrabia, A. Growth hormone production and role in the reproductive system of female chicken. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2015, 220, 112–118.

- Owen, E.J.; West, C.; Mason, B.A.; Jacobs, H.S. Co-treatment with growth hormone of sub-optimal responders in IVF-ET. Hum. Reprod. 1991, 6, 524–528.

- Bassiouny, Y.A.; Dakhly, D.M.R.; Bayoumi, Y.A.; Hashish, N.M. Does the addition of growth hormone to the in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection antagonist protocol improve outcomes in poor responders? A randomized, controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 105, 697–702.

- Li, X.-L.; Wang, L.; Lv, F.; Huang, X.-M.; Wang, L.-P.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, X.-M. The influence of different growth hormone addition protocols to poor ovarian responders on clinical outcomes in controlled ovary stimulation cycles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2017, 96, e6443.

- Chu, K.; Pang, W.; Sun, N.; Zhang, Q.; Li, W. Outcomes of poor responders following growth hormone co-treatment with IVF/ICSI mild stimulation protocol: A retrospective cohort study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 297, 1317–1321.

- Cai, M.-H.; Liang, X.-Y.; Wu, Y.-Q.; Huang, R.; Yang, X. Six-week pretreatment with growth hormone improves clinical outcomes of poor ovarian responders undergoing in vitro fertilization treatment: A self-controlled clinical study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2019, 45, 376–381.

- Choe, S.-A.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, J.; Chang, E.M.; Kim, J.W.; Park, H.M.; Lyu, S.W.; Lee, W.S.; Yoon, T.K.; et al. Increased proportion of mature oocytes with sustained-release growth hormone treatment in poor responders: A prospective randomized controlled study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 297, 791–796.

- Homburg, R.; Levy, T.; Ben-Rafael, Z. Adjuvant growth hormone for induction of ovulation with gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist and gonadotrophins in polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Hum. Reprod. 1995, 10, 2550–2553.

- Gong, Y.; Luo, S.; Fan, P.; Jin, S.; Zhu, H.; Deng, T.; Quan, Y.; Huang, W. Growth hormone alleviates oxidative stress and improves oocyte quality in Chinese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18769.

- Li, J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Huang, G.; Ye, H. Does growth hormone supplementation improve oocyte competence and IVF outcomes in patients with poor embryonic development? A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 310.

- Chen, Q.-L.; Shuai, J.; Chen, W.-H.; Zhang, X.-D.; Pei, L.; Huang, G.-N.; Ye, H. Impact of growth hormone supplementation on improving oocyte competence in unexplained poor embryonic development patients of various ages. Gynecol. Endocrinol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2021, 38, 1–7.

- Gallardo, T.D.; John, G.B.; Bradshaw, K.; Welt, C.; Reijo-Pera, R.; Vogt, P.H.; Touraine, P.; Bione, S.; Toniolo, D.; Nelson, L.M.; et al. Sequence variation at the human FOXO3 locus: A study of premature ovarian failure and primary amenorrhea. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 216–221.

- Orisaka, M.; Miyazaki, Y.; Shirafuji, A.; Tamamura, C.; Tsuyoshi, H.; Tsang, B.K.; Yoshida, Y. The role of pituitary gonadotropins and intraovarian regulators in follicle development: A mini-review. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2021, 20, 169–175.

- Carlsson, I.B.; Scott, J.E.; Visser, J.A.; Ritvos, O.; Themmen, A.P.N.; Hovatta, O. Anti-Müllerian hormone inhibits initiation of growth of human primordial ovarian follicles in vitro. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 2223–2227.

- Rodgers, R.J.; Abbott, J.A.; Walters, K.A.; Ledger, W.L. Translational Physiology of Anti-Müllerian Hormone: Clinical Applications in Female Fertility Preservation and Cancer Treatment. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 689532.

- Zaczek, D.; Hammond, J.; Suen, L.; Wandji, S.; Service, D.; Bartke, A.; Chandrashekar, V.; Coschigano, K.; Kopchick, J. Impact of growth hormone resistance on female reproductive function: New insights from growth hormone receptor knockout mice. Biol. Reprod. 2002, 67, 1115–1124.

- Chandrashekar, V.; Zaczek, D.; Bartke, A. The consequences of altered somatotropic system on reproduction. Biol. Reprod. 2004, 71, 17–27.

- Saccon, T.D.; Rovani, M.T.; Garcia, D.N.; Mondadori, R.G.; Cruz, L.A.X.; Barros, C.C.; Bartke, A.; Masternak, M.M.; Schneider, A. Primordial follicle reserve, DNA damage and macrophage infiltration in the ovaries of the long-living Ames dwarf mice. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 132, 110851.

- Saccon, T.D.; Moreira, F.; Cruz, L.A.; Mondadori, R.G.; Fang, Y.; Barros, C.C.; Spinel, L.; Bartke, A.; Masternak, M.M.; Schneider, A. Ovarian aging and the activation of the primordial follicle reserve in the long-lived Ames dwarf and the short-lived bGH transgenic mice. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 455, 23–32.

- Liu, X.; Andoh, K.; Yokota, H.; Kobayashi, J.; Abe, Y.; Yamada, K.; Mizunuma, H.; Ibuki, Y. Effects of growth hormone, activin, and follistatin on the development of preantral follicle from immature female mice. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 2342–2347.

- Martins, F.S.; Celestino, J.J.H.; Saraiva, M.V.A.; Chaves, R.N.; Rossetto, R.; Silva, C.M.G.; Lima-Verde, I.B.; Lopes, C.A.P.; Campello, C.C.; Figueiredo, J.R. Interaction between growth differentiation factor 9, insulin-like growth factor I and growth hormone on the in vitro development and survival of goat preantral follicles. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2010, 43, 728–736.

- Ménézo, Y.J.; el Mouatassim, S.; Chavrier, M.; Servy, E.J.; Nicolet, B. Human oocytes and preimplantation embryos express mRNA for growth hormone receptor. Zygote 2003, 11, 293–297.

- Pereira, G.R.; Lorenzo, P.L.; Carneiro, G.F.; Ball, B.A.; Bilodeau-Goeseels, S.; Kastelic, J.; Pegoraro, L.M.C.; Pimentel, C.A.; Esteller-Vico, A.; Illera, J.C.; et al. The involvement of growth hormone in equine oocyte maturation, receptor localization and steroid production by cumulus-oocyte complexes in vitro. Res. Vet. Sci. 2013, 95, 667–674.

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Yu, Q.; Liu, H.; Huang, T.; Zhao, S.; Ma, J.; Zhao, H. Growth Hormone Promotes in vitro Maturation of Human Oocytes. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 485.

- Mendoza, C.; Ruiz-Requena, E.; Ortega, E.; Cremades, N.; Martinez, F.; Bernabeu, R.; Greco, E.; Tesarik, J. Follicular fluid markers of oocyte developmental potential. Hum. Reprod. 2002, 17, 1017–1022.

- Dakhly, D.M.R.; Bassiouny, Y.A.; Bayoumi, Y.A.; Hassan, M.A.; Gouda, H.M.; Hassan, A.A. The addition of growth hormone adjuvant therapy to the long down regulation protocol in poor responders undergoing in vitro fertilization: Randomized control trial. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 228, 161–165.

- Kucuk, T.; Kozinoglu, H.; Kaba, A. Growth hormone co-treatment within a GnRH agonist long protocol in patients with poor ovarian response: A prospective, randomized, clinical trial. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2008, 25, 123–127.

- Dogan, S.; Cicek, O.S.Y.; Demir, M.; Yalcinkaya, L.; Sertel, E. The effect of growth hormone adjuvant therapy on assisted reproductive technologies outcomes in patients with diminished ovarian reserve or poor ovarian response. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 50, 101982.

- Weall, B.M.; Al-Samerria, S.; Conceicao, J.; Yovich, J.L.; Almahbobi, G. A direct action for GH in improvement of oocyte quality in poor-responder patients. Reproduction 2015, 149, 147–154.

- Regan, S.L.P.; Knight, P.G.; Yovich, J.L.; Arfuso, F.; Dharmarajan, A. Growth hormone during in vitro fertilization in older women modulates the density of receptors in granulosa cells, with improved pregnancy outcomes. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 1298–1310.

- Kaiser, G.G.; Kölle, S.; Boie, G.; Sinowatz, F.; Palma, G.A.; Alberio, R.H. In vivo effect of growth hormone on the expression of connexin-43 in bovine ovarian follicles. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2006, 73, 600–606.

- Payne, A.H.; Hales, D.B. Overview of steroidogenic enzymes in the pathway from cholesterol to active steroid hormones. Endocr. Rev. 2004, 25, 947–970.

- Miller, W.L.; Auchus, R.J. The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders. Endocr. Rev. 2011, 32, 81–151.

- Kobayashi, J.; Mizunuma, H.; Kikuchi, N.; Liu, X.; Andoh, K.; Abe, Y.; Yokota, H.; Yamada, K.; Ibuki, Y.; Hagiwara, H. Morphological assessment of the effect of growth hormone on preantral follicles from 11-day-old mice in an in vitro culture system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 268, 36–41.

- Nakamura, E.; Otsuka, F.; Inagaki, K.; Miyoshi, T.; Matsumoto, Y.; Ogura, K.; Tsukamoto, N.; Takeda, M.; Makino, H. Mutual regulation of growth hormone and bone morphogenetic protein system in steroidogenesis by rat granulosa cells. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 469–480.

- Lanzone, A.; Fortini, A.; Fulghesu, A.M.; Soranna, L.; Caruso, A.; Mancuso, S. Growth hormone enhances estradiol production follicle-stimulating hormone-induced in the early stage of the follicular maturation. Fertil. Steril. 1996, 66, 948–953.

- Ferreira, A.C.A.; Maside, C.; Sá, N.A.R.; Guerreiro, D.D.; Correia, H.H.V.; Leiva-Revilla, J.; Lobo, C.H.; Araújo, V.R.; Apgar, G.A.; Brandão, F.Z.; et al. Balance of insulin and FSH concentrations improves the in vitro development of isolated goat preantral follicles in medium containing GH. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2016, 165, 1–10.

- Ahumada-Solórzano, S.M.; Martínez-Moreno, C.G.; Carranza, M.; Ávila-Mendoza, J.; Luna-Acosta, J.L.; Harvey, S.; Luna, M.; Arámburo, C. Autocrine/paracrine proliferative effect of ovarian GH and IGF-I in chicken granulosa cell cultures. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2016, 234, 47–56.

- Kopchick, J.J.; Parkinson, C.; Stevens, E.C.; Trainer, P.J. Growth hormone receptor antagonists: Discovery, development, and use in patients with acromegaly. Endocr. Rev. 2002, 23, 623–646.

- Takahashi, Y. The Role of Growth Hormone and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I in the Liver. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1447.

- Dehkhoda, F.; Lee, C.M.M.; Medina, J.; Brooks, A.J. The Growth Hormone Receptor: Mechanism of Receptor Activation, Cell Signaling, and Physiological Aspects. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 35.

- Kang, S.K.; Tai, C.J.; Cheng, K.W.; Leung, P.C. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone activates mitogen-activated protein kinase in human ovarian and placental cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2000, 170, 143–151.

- Seger, R.; Hanoch, T.; Rosenberg, R.; Dantes, A.; Merz, W.E.; Strauss, J.F., 3rd; Amsterdam, A. The ERK signaling cascade inhibits gonadotropin-stimulated steroidogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 8847.

- Moore, R.K.; Otsuka, F.; Shimasaki, S. Role of ERK1/2 in the differential synthesis of progesterone and estradiol by granulosa cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 289, 796–800.

- Rowlinson, S.W.; Yoshizato, H.; Barclay, J.L.; Brooks, A.J.; Behncken, S.N.; Kerr, L.M.; Millard, K.; Palethorpe, K.; Nielsen, K.; Clyde-Smith, J.; et al. An agonist-induced conformational change in the growth hormone receptor determines the choice of signalling pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 740–747.

- Manna, P.R.; Huhtaniemi, I.T.; Stocco, D.M. Mechanisms of protein kinase C signaling in the modulation of 3’,5’-cyclic adenosine monophosphate-mediated steroidogenesis in mouse gonadal cells. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 3308–3317.

- Niswender, G.D. Molecular control of luteal secretion of progesterone. Reproduction 2002, 123, 333–339.

- Casarini, L.; Crépieux, P. Molecular Mechanisms of Action of FSH. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 305.

- Puri, P.; Little-Ihrig, L.; Chandran, U.; Law, N.C.; Hunzicker-Dunn, M.; Zeleznik, A.J. Protein Kinase A: A Master Kinase of Granulosa Cell Differentiation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28132.

- Liang, A.; Plewes, M.R.; Hua, G.; Hou, X.; Blum, H.R.; Przygrodzka, E.; George, J.W.; Clark, K.L.; Bousfield, G.R.; Butnev, V.Y.; et al. Bioactivity of recombinant hFSH glycosylation variants in primary cultures of porcine granulosa cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020, 514, 110911.

- Mukherjee, A.; Park-Sarge, O.K.; Mayo, K.E. Gonadotropins induce rapid phosphorylation of the 3’,5’-cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein in ovarian granulosa cells. Endocrinology 1996, 137, 3234–3245.

- Słuczanowska-Głąbowska, S.; Laszczyńska, M.; Piotrowska, K.; Głąbowski, W.; Kopchick, J.J.; Bartke, A.; Kucia, M.; Ratajczak, M.Z. Morphology of ovaries in laron dwarf mice, with low circulating plasma levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and in bovine GH-transgenic mice, with high circulating plasma levels of IGF-1. J. Ovarian Res. 2012, 5, 18.

- Isola, J.V.V.; Zanini, B.M.; Sidhom, S.; Kopchick, J.J.; Bartke, A.; Masternak, M.M.; Stout, M.B.; Schneider, A. 17α-Estradiol promotes ovarian aging in growth hormone receptor knockout mice, but not wild-type littermates. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 129, 110769.

- Jones, J.I.; Clemmons, D.R. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins: Biological actions. Endocr. Rev. 1995, 16, 3–34.

- Baumgarten, S.C.; Armouti, M.; Ko, C.; Stocco, C. IGF1R Expression in Ovarian Granulosa Cells Is Essential for Steroidogenesis, Follicle Survival, and Fertility in Female Mice. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 2309–2318.

- Zhou, J.; Kumar, T.R.; Matzuk, M.M.; Bondy, C. Insulin-like growth factor I regulates gonadotropin responsiveness in the murine ovary. Mol. Endocrinol. 1997, 11, 1924–1933.

- Lavranos, T.C.; O’Leary, P.C.; Rodgers, R.J. Effects of insulin-like growth factors and binding protein 1 on bovine granulosa cell division in anchorage-independent culture. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1996, 107, 221–228.

- Spicer, L.J.; Aad, P.Y. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) 2 stimulates steroidogenesis and mitosis of bovine granulosa cells through the IGF1 receptor: Role of follicle-stimulating hormone and IGF2 receptor. Biol. Reprod. 2007, 77, 18–27.

- Das, M.; Sauceda, C.; Webster, N.J.G. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Obesity and Reproduction. Endocrinology 2021, 162, bqaa158.

- Roth, Z. Symposium review: Reduction in oocyte developmental competence by stress is associated with alterations in mitochondrial function. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3642–3654.

- Wang, L.; Tang, J.; Wang, L.; Tan, F.; Song, H.; Zhou, J.; Li, F. Oxidative stress in oocyte aging and female reproduction. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 7966–7983.

- Ostadmohammadi, V.; Jamilian, M.; Bahmani, F.; Asemi, Z. Vitamin D and probiotic co-supplementation affects mental health, hormonal, inflammatory and oxidative stress parameters in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Ovarian Res. 2019, 12, 5.

- Samimi, M.; Pourhanifeh, M.H.; Mehdizadehkashi, A.; Eftekhar, T.; Asemi, Z. The role of inflammation, oxidative stress, angiogenesis, and apoptosis in the pathophysiology of endometriosis: Basic science and new insights based on gene expression. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 19384–19392.

- Gong, Y.; Luo, S.; Fan, P.; Zhu, H.; Li, Y.; Huang, W. Growth hormone activates PI3K/Akt signaling and inhibits ROS accumulation and apoptosis in granulosa cells of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2020, 18, 121.

- John, G.B.; Shidler, M.J.; Besmer, P.; Castrillon, D.H. Kit signaling via PI3K promotes ovarian follicle maturation but is dispensable for primordial follicle activation. Dev. Biol. 2009, 331, 292–299.

- Grosbois, J.; Demeestere, I. Dynamics of PI3K and Hippo signaling pathways during in vitro human follicle activation. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 1705–1714.

- Caicedo, D.; Díaz, O.; Devesa, P.; Devesa, J. Growth Hormone (GH) and Cardiovascular System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 290.

- Chung, J.-Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, M. The protective effect of growth hormone on Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase-mutant motor neurons. BMC Neurosci. 2015, 16, 1.

- Wang, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Wu, C.; Zhou, P. Growth hormone protects against ovarian granulosa cell apoptosis: Alleviation oxidative stress and enhancement mitochondrial function. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 21, 100504.

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, H.-H.; Ma, X.-S.; Qian, W.-P.; Shen, W.; Schatten, H.; Sun, Q.-Y. SIRT1, 2, 3 protect mouse oocytes from postovulatory aging. Aging 2016, 8, 685–696.