Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Koji Miyabayashi | -- | 2961 | 2022-09-26 10:42:29 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 2961 | 2022-09-26 11:04:08 | | | | |

| 3 | Camila Xu | + 51 word(s) | 3012 | 2022-09-28 08:40:49 | | | | |

| 4 | Koji Miyabayashi | + 6 word(s) | 3018 | 2022-09-28 09:12:02 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Miyabayashi, K.; Ijichi, H.; Fujishiro, M. The Role of the Microbiome in Pancreatic Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/27581 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Miyabayashi K, Ijichi H, Fujishiro M. The Role of the Microbiome in Pancreatic Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/27581. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Miyabayashi, Koji, Hideaki Ijichi, Mitsuhiro Fujishiro. "The Role of the Microbiome in Pancreatic Cancer" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/27581 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Miyabayashi, K., Ijichi, H., & Fujishiro, M. (2022, September 26). The Role of the Microbiome in Pancreatic Cancer. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/27581

Miyabayashi, Koji, et al. "The Role of the Microbiome in Pancreatic Cancer." Encyclopedia. Web. 26 September, 2022.

Copy Citation

The microbiome is now known to be associated with cancer development and progression in many types of cancer including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Many observational studies have revealed the association of the oral, gut, and intratumor microbiome with human PDAC. The microbiome may affect the composition of tumor microenvironment via the immune response and generate an immunosuppressive environment. The microbiome could be a biomarker for the prediction of an immunogenic tumor microenvironment and immune-targeted therapies.

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)

microbiome

tumor microenvironment

1. Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a deadly cancer worldwide, and it has a five-year survival rate of less than 9% for all the stages combined [1]. More than half of PDAC patients are diagnosed as inoperable with metastatic diseases or advanced diseases. PDAC frequently recurs even after resection, and chemotherapies are frequently ineffective. Early diagnosis methods and new therapeutic strategies are needed.

According to the development of the genetic and molecular characterization of PDAC, tailored therapies have emerged. Recent studies have suggested that up to 25% of PDACs have actionable genetic mutations [2] and three subgroups of PDAC patients are considered to be possibly targeted by tailored therapies. Patients with gene alterations of homologous recombination deficiency (HRD), such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, benefit from platinum-based therapy and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors [3][4][5][6][7][8]. Patients with mismatch repair deficiency (MMR-D), including high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) and high tumor gene mutation burden (TMB-H), can be targeted by immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapies [2][9]. Patients with wild-type KRAS (KRASWT) often have alternative oncogenic mutations, such as BRAF [3][5], and may be candidates for small-molecule therapies.

Although ICB is a promising therapy in many types of cancers as well as PDAC, biomarkers for the efficacy of treatment are still unknown in PDAC. Clinical trials showed that MMR-D patients in PDAC are resistant to ICB therapies compared to other types of cancer [2][9]. PDAC is characterized by a dense stromal component that interacts with cancer cells and serves as a tumor-supportive environment [10]. Tumor-infiltrating T cells play an important role in eliminating tumor cells, and these components are regulated by other types of cells in tumor microenvironment (TME) such as fibroblasts, macrophages, and dendritic cells [11]. Cancer cells orchestrate stromal cells to create an immunosuppressive environment that is favorable to cancer cells. Dense stroma creating an immunosuppressive TME is one of the reasons for the complexity of chemoresistance in PDAC. Intrinsic factors in PDAC cells as well as extrinsic factors in non-cancer cells are associated with the formation of immunosuppressive TME. A comprehensive analysis of PDAC using multi-omics studies, including the microbiome, would contribute to the understanding of complexed TME and the establishment of new therapeutic strategies.

The microbiome is now known to be associated with cancer development and progression in many types of cancer [12]. Several studies have revealed the association between PDAC progression and the oral, gut, and intratumor microbiomes, although the identified bacteria differ between reports [13]. These reports have commonly reported that high microbial diversity is associated with favorable outcomes. Bacteria are thought to migrate from the gut to the pancreas, and a recent report has suggested that the gut microbiota modifies the overall microbiome of tumors [14][15]. Regarding the early detection of PDAC, evidence is accumulating to suggest that the microbiome is associated with premalignant diseases of the pancreas, such as chronic pancreatitis (CP) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia (IPMN) [16][17]. Although further studies are needed to understand whether the differences in the microbiome in pancreatic precursors of PDAC are a cause or a consequence, the microbiome has a potential role in the early detection of PDAC. Regarding the treatment of PDAC, intratumor CD8 + T cell infiltration may play an important role in microbiome-associated immune modification [15]. The microbiome can be a biomarker of the efficacy of ICB therapies. Furthermore, antibiotic treatment may provide new options to modify the efficacy of chemotherapies as well as ICB therapies.

2. Mechanisms of Role of Microbiomes in PDAC

2.1. Association of Microbiomes with Molecular Subtypes of Cancer Cell

In recent years, intense genomic analyses have been performed to reveal the mutational landscape of PDAC [18][19][20][21]. The frequently reported genetic mutations are concentrated in core signaling pathways including KRAS, WNT, NOTCH, DNA damage repair, RNA processing, cell-cycle regulation, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling, switch or sucrose non-fermentable (SWI/SNF), chromatin regulation, and axonal guidance [18][19][20][21]. Recent comprehensive sequencing analysis elucidated transcriptional molecular subtypes of the cancer cells of PDAC including basal-like or squamous and classical or progenitor subtypes. Basal-like or squamous tumors are associated with poor outcomes and treatment resistance compared to classical or progenitor subtypes [21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30]. In addition to genome-based precision medicine, tailored therapies based on transcriptomic subtypes have emerged. Recent clinical trials have revealed that basal-like tumors are resistant to FOLFIRINOX-based therapies [30][31]. These results were supported by a study using patient-derived organoids (PDOs) by Tiriac et al. [32], who showed that chemotherapy signatures based on PDO could predict the treatment response in PDAC patients. Although the underlying mechanisms of this chemoresistance in basal-like tumors are still unknown, subgroups in basal-like subtypes characterized by the activation of KRAS, MYC, ∆N isoform of TP63 (∆Np63), and GLI2 [21][23][24][33][34][35][36][37][38] may be the key to solving the problem.

An association between the molecular subtypes and microbiome was recently reported, identifying a high abundance of Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, and Sphingopyxis in basal-like human PDAC, and the analysis of microbial genes suggested the potential of the microbiome in inducing pathogen-related inflammation [39].

2.2. Role of Microbiomes in TME

In recent studies, single-cell RNA sequencing has been used to reveal the heterogeneity of stromal components [40][41][42][43]. CAFs play an important role in the regulation of the TME, and it has been reported that cancer-derived IL-1 or TGF-β can differentiate surrounding fibroblasts into inflammatory and myofibroblastic CAFs, respectively [41]. IL-6 secreted by inflammatory CAFs promote tumor growth, while myofibroblastic CAFs produce surrounding stroma. Since cancer cells create a microenvironment favorable to themselves, these stromal subtypes are related to the cancer-cell subtypes described above. Maurer et al. [26] reported CAF subtypes by RNA sequencing separately harvested PDAC epithelium and adjacent stroma using laser capture microdissection. The researchers identified two subtypes that reflect ECM deposition and remodeling (ECM-rich) versus immune-related processes (immune-rich). ECM-rich stroma was strongly associated with basal-like tumors, while immune-rich stroma was more frequently associated with classical tumors [26][44]. Thus, the cancer cell subtypes and stromal subtypes were partially related, suggesting that they can be potential biomarkers for therapies targeting stroma in PDAC.

Dense stroma with desmoplastic reaction may act as a physical barrier and affect the infiltration of MDSCs and T cells in TME [45][46]. In addition, PDAC shows substantial immunological heterogeneity influencing T-cell infiltration [47][48][49][50][51][52][53], the level of T-cell infiltration is important in predicting the efficacy of ICB therapies, and patients with MSI-H tumors show abundant TILs and sensitivity to immune-targeted therapies [54][55][56][57][58][59][60]. Studies in mouse models have revealed potential targets, such as colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 [61][62], and CXC chemokine receptor 2 [63][64] in combination with ICB, which have been tested in clinical trials. These results suggest that both the quality and quantity of CD8 + T cells in tumors are important in predicting the efficacy of immunotherapy, and that new biomarkers are needed to predict the status of infiltrating CD8 + T cells in tumors.

As an association between microbiome and CAF subtypes was not clear, the microbiome was associated with the inflammatory and immunosuppressive TME in mice.

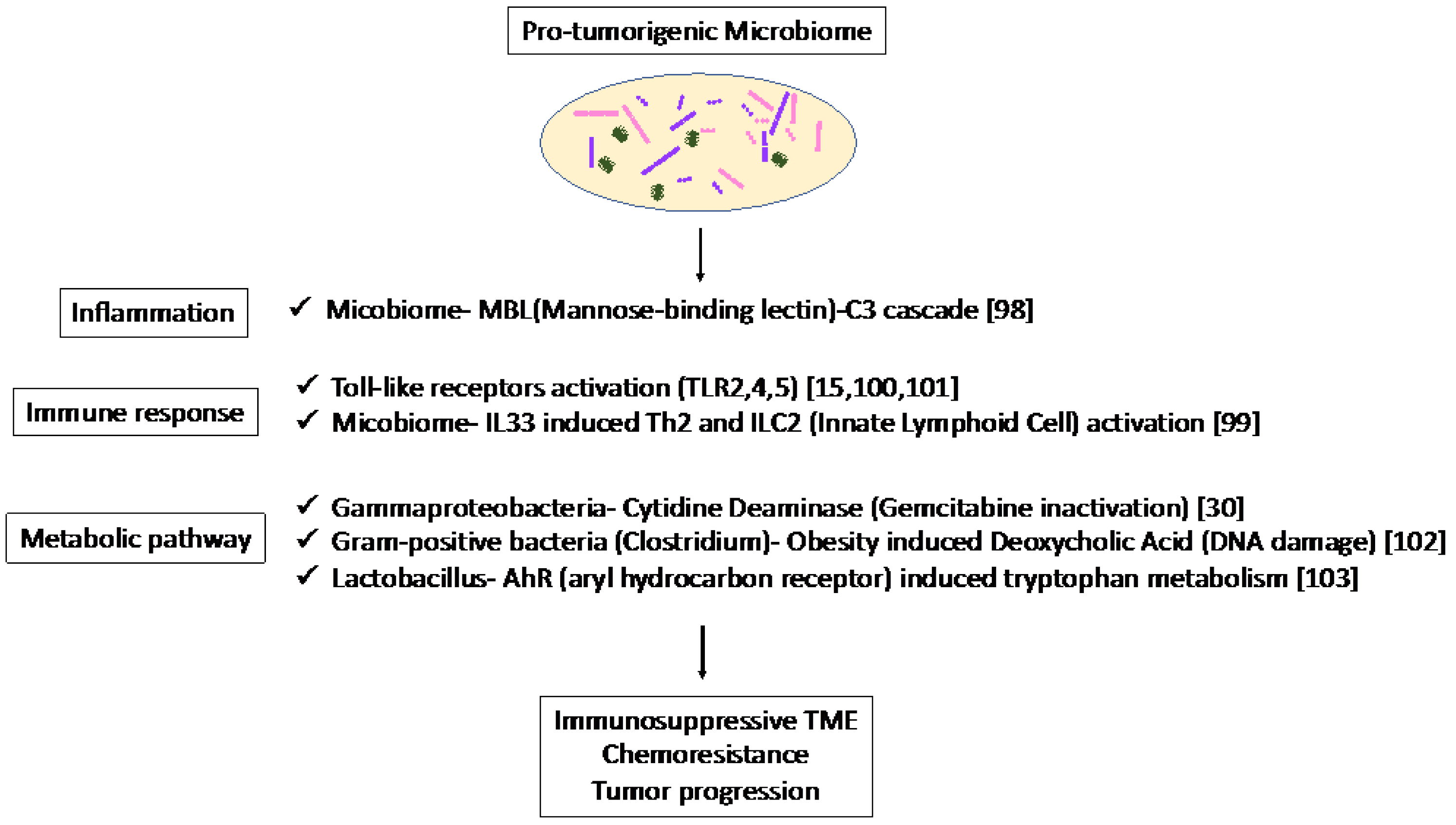

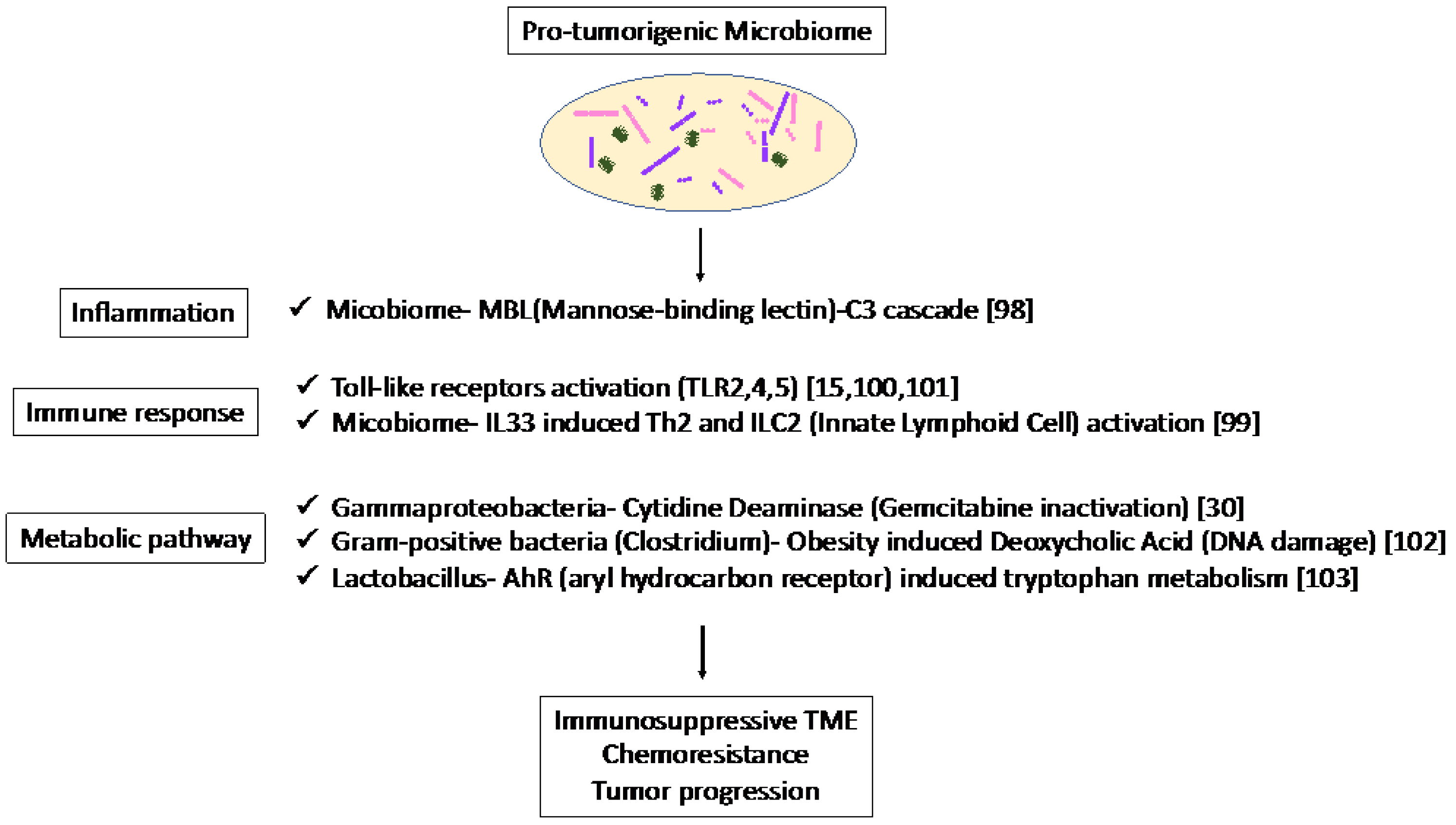

The association of the mycobiome with the complement system has been reported [65]. The mycobiome promoted tumor growth due to mannose-binding lectin(MBL)–C3 cascade in a genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM) [65]. The complement system is an important component of the inflammatory response, which is involved in tumorigenesis and the adaptive immune response, which modulates T cell activation. The mycobiome has also been reported to enhance oncogenic KrasG12D-induced IL-33 secretion from PDAC and activates TH2 and ILC2 cells, which contribute to tumor progression using GEMM [66]. Anti-IL-33 or anti-fungal treatment decreases TH2 and ILC2 infiltration and increases the survival in GEMM.

Microbiota-induced activation of toll-like receptors (TLRs), especially TLR9, activate pancreatic cancer stellate cells and attract immunosuppressive T regulatory cells and MDSCs to the tumor environment, which contribute to the suppression of innate and adaptive immunity in PDAC progression in mice [67]. Lipopolysaccharide and TLR4 ligation induce a dendritic-cell-dependent immune response in the pancreas and increase pancreatic tumorigenesis, where Myd88 inhibition induced fibroinflammation via dendritic cells andTh2-derived CD4 T cells [68]. In addition, microbiota-mediated TLR2 and TLR5 ligation alters macrophages into an immunosuppressive phenotype and suppresses the T-cell-mediated antitumor immune response in mice [15]. Furthermore, microbial metabolism and metabolites can alter the TME. Obesity alters the gut microbiota and increases the level of the microbial metabolite deoxycholic acid (DCA), which induces DNA damage in obesity-associated hepatocellular carcinoma development in mice [69]. This metabolite may also be a risk factor for obesity-induced PDAC. Hezaveh et al. [70] showed that the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), which is a sensor of products of tryptophan metabolism, modulates immunity due to tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) function in murine PDAC. TAMs AhR activity was dependent on Lactobacillus metabolization of dietary tryptophan to indoles. Inhibition of AhR in myeloid cells reduced PDAC growth due to increased infiltration of IFNγ + CD8 + T cells in murine PDAC tumor [70]. Moreover, cytidine deaminase, an enzyme expressed by many bacteria, converts active gemcitabine into an inactive metabolite in colon cancer mouse models. Gamma Proteobacteria are reported to present in PDAC tumors and induce resistance to gemcitabine via cytidine deaminase [71]. Therefore, when antibiotics are used to reduce the bacteria, resistance to gemcitabine is eliminated. Thus, microbiome-based therapy may be useful not only for the suppression of carcinogenesis but also for preventing resistance to treatment.

Thus, the microbiome plays a pro-tumorigenic role via inflammation, immune response, and metabolic pathways (Figure 1). These results suggest the potential of the microbiome as a biomarker in immunotherapy and microbiome-targeted therapies.

Figure 1. Specific microbiota and associated metabolic and biochemical pathways.

3. Role of Microbiomes in PDAC Treatment

3.1. Current Immunotherapy in PDAC

ICB therapies represent an effective treatment for patients with MMR-D/MSI-H regardless of the tumor type, but their activity depends on the tumor type. MMR-D is caused by the loss of function of MMR genes (MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, MSH6) due to hereditary germline mutations, known as Lynch syndrome, and biallelic somatic mutations of MMR genes. MMR-D and MSI-H are commonly associated with a high tumor gene mutation burden (TMB). High TMBs are thought to increase the number of neoantigens that are recognized by the host immune system, and activated tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), especially CD8 + T cells, migrate into TME and play an important role in antitumor response [47][51].

The degree of T-cell infiltration in tumors is critical for predicting the efficacy of ICB therapy in other types of cancers [54][55][56][57][58][59], and a small subset of patients with MSI-H tumors exhibit T-cell infiltration and sensitivity to immunotherapy [60]. In PDAC, only 1% of patients have MMR-D or MSI-H [72][73]. In addition, ICB therapy is less effective in PDAC compared to other cancer types in the KEYNOTE 158 study [9] and NCI-MATCH study [2]. These results suggest that ICB responses depend on cancer-type-specific biological factors, even in patients with MMR-D. Furthermore, some MMR gene mutations may be passenger mutations, and responses to ICB therapy may be influenced by founder mutations that are important for the molecular behavior of cancer [74]. In case these markers are highly associated with MMR-D-driven tumorigenesis, MSI-H and high TMB may be a biomarker of the ICB response [75]. Further prospective studies are needed to discover a biomarker to predict intratumor T-cell infiltration and the ICB response in PDAC. In addition to ICB therapies, a variety of immune-targeted approaches have been tested in clinical trials with PDAC patients including tumor vaccines [76], such as PEGylated interleukin (IL)-10 [77] and GVAX, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-transfected tumor cells [78], and CAR(T) therapy, which showed limited success [79].

3.2. Role of Microbiomes as Biomarkers for Immunotherapy and Chemotherapy in PDAC

The association between the microbiome and the response of immunotherapy was reported in other types of cancer [80][81][82]. In these studies, the fecal microbiota of responders and non-responders to ICB therapy were compared. They reconstituted the germ-free (GF) mice with stool from the responders and specific candidate bacteria and succeeded in recreating the response to immunotherapy. Matson et al. [82] identified Bifidobacteriaceae, Collinsella aerofaciens, and Enterococcus faecium, and Gopalakrishnan et al. [81] identified Fecalibacterium spp. in melanoma patients. Routy et al. [80] identified Akkermansia muciniphila in lung cancer, renal cancer, and bladder cancer. In PDAC, Pushalkar et al. [15] recently reported that the depletion of the gut microbiome enhances the effect of ICB therapy. A recent study by Riquelme and colleagues [14] showed that the composition of the pancreatic tumor microbiome influences patient survival. In particular, a diverse intratumor microbiome signature enriched with Pseudoxanthomonas, Streptomyces, Sacchropolyspora, and Bacillus clausii predicted long-term survival in multiple patient cohorts [14]. It is very interesting to note that these studies identified different bacteria-affecting responses to ICB therapy, possibly due to the differences in cancer types and the environments. In order to reach a clear consensus on the definition of good and bad bacteria in cancer immunotherapy, multicenter cohorts around the world need to be studied.

As mentioned above, using a colorectal cancer model, Geller et al. [71] found that bacteria metabolize the gemcitabine (2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine), which is a common chemotherapeutic drug for PDAC to an inactive form, 2′,2′-difluorodeoxyuridine. A long isoform of the bacterial enzyme cytidine deaminase (CDDL) was expressed primarily in gamma Proteobacteria, which was involved in gemcitabine resistance in tumors, and administration of the antibiotic abrogated the gemcitabine resistance. They reported that 76% (86/113) of PDACs were mainly positive for gamma Proteobacteria.

3.3. Key Challenges and Limitations in Experiments of Microbiomes in PDAC

To elucidate the role of the microbiome in PDAC treatment, mouse models are commonly used. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) was performed in immunocompetent mice after antibiotic treatment to analyze the role of fecal microbiota of interest in tumor formation [80][81][83]. Genetically engineered mouse models and orthotopic transplantation mouse models enable the analysis of the role of the microbiome in the formation of immunosuppressive TME including T-cell infiltration in tumors. However, the human microbiome not only differs significantly from that of the mouse but also among humans [84][85]. The gut microbiome is altered by a variety of factors including nutrition, antibiotics, probiotics, geography, and age [86], and the gut bacteria is considered to be influenced by the environment much more than ethnicity, race, and genetic background [87][88]. In addition, the rodent gut microbiota varies from laboratory to laboratory and source to source [89][90], creating problems with reproducibility in preclinical studies. To solve these problems, studies using the aforementioned mouse models are useful; the crosstalk between the microbiome and immunity has been well-studied [80][81][83] and the microbiome has been found to play an important role in cancer.

3.4. Antibiotic Treatment and Bacterial Transplantation Therapy in PDAC

The impact of microbiome ablation on PDAC development has been tested by antibiotic therapy as well as the activation of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as TLR4 [68], TLR7 [91], Dectin [92], the NLRP3 inflammasome [93] in immune cells, and TLR9 in pancreatic stellate cells promotes carcinogenesis in the pancreas [67], which was abrogated by oral antibiotics. Thomas et al. [94] reported that KrasG12D/+;PTENlox/+ mice depleted of microbes via antibiotics had a reduced percentage of poorly differentiated tumors compared to KrasG12D/+;PTENlox/+ mice with intact microbes. Sethi et al. [95] reported that eradicating the microbiome with oral antibiotics significantly reduced the tumor volume in PDAC models as well as melanoma and colorectal cancer in an adaptive immune-dependent manner. The researchers showed that decreasing the gut bacteria significantly increased interferon gamma-producing T cells and decreased in interleukin 17A- and interleukin 10-producing T cells, suggesting that modulation of the gut bacteria may be a new immunotherapy strategy. Pushalkar et al. [15] reported that the pancreases of PDAC patients contain more Proteobacteria, Euyarchaeota, and Synergistetes than normal pancreases, and ablation of the microbiota showed an enhanced effect of ICB in PDAC. The researchers reported that the removal of the microbiome suppresses the development of both pre-invasive and invasive PDAC but the transfer of bacteria from tumor-bearing hosts promotes tumors. Bacterial removal was associated with immunogenic reprogramming of the TME in PDAC, including a decrease in MDSCs and an increase in M1 macrophage, which promoted Th1 differentiation of CD4+ T cells and activation of CD8+ T cells. These data suggest that endogenous microbes promote the immunosuppressive TME of PDAC and that microbial ablation is a promising approach to inhibit the progression of PDAC. However, a contrary effect of microbial ablation has been reported in other types of cancer [96][97][98], suggesting that the antibiotic effects are context-dependent. A phase I trial examining the effects of microbiome ablation in human PDAC may answer important questions about the role of specific microbiota in anti-tumor immunity (NCT03891979xii). Patients with resectable PDAC receive antibiotics and ICB therapy for 4 weeks before surgical resection. To reveal the effect of microbiome regulation in the immunotherapy of human PDAC, analysis of tumor tissue provides clues for markers of immune cell activation. Using treatment-naïve primary tumors enables answering how the removal of the microbiome contributes to changes in stromal and immune cell activity. Further studies are needed to evaluate the effect of antibacterial treatment on the tumor microenvironment and the efficacy of combining drugs including ICB therapies.

Riquelme et al. [14] performed human fecal microbiota transplants from PDAC patients, PDAC survivors, and healthy controls to tumor-bearing mice to evaluate the role of the gut microbiome in shaping the tumor microbiome, the immune system, and PDAC progression. The researchers showed that gut or tumor microbiomes from PDAC survivors induced an antitumor response and enhanced the infiltration of CD8+ T cell in tumor-bearing mice, which was due to the decreased tumor infiltration of regulatory T cells (Tregs). These data suggested the causal role of the microbiome on the tumor microenvironment. As such, bacterial transplantation is a potential strategy for PDAC treatment. The efficacy of oral administration of a single or consortium of bacterial species as well as engineered non-pathogenic bacteria have been reported in other types of cancer [99][100][101]. Sivan et al. [99] reported that oral administration of Bifidobacterium alone improved antitumor immunity due to enhanced CD8+ T cell priming by augmented dendritic cell function in melanoma. Chowdhury et al. [101] engineered a non-pathogenic Escherichia coli strain which released an encoded nanobody antagonist of CD47 within the tumor microenvironment, stimulating the tumor-infiltrating T cells and systemic tumor-antigen-specific immune responses. In PDAC, these novel technologies are largely unexplored. Further analyses in preclinical and clinical studies are needed to test the efficacy of bacterio-therapies in PDAC.

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33.

- Azad, N.S.; Gray, R.J.; Overman, M.J.; Schoenfeld, J.D.; Mitchell, E.P.; Zwiebel, J.A.; Sharon, E.; Streicher, H.; Li, S.; McShane, L.M.; et al. Nivolumab is effective in mismatch repair-deficient noncolorectal cancers: Results from arm Z1D-A subprotocol of the NCI-MATCH (EAY131) study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 214–222.

- Aguirre, A.J.; Nowak, J.A.; Camarda, N.D.; Moffitt, R.A.; Ghazani, A.A.; Hazar-Rethinam, M.; Raghavan, S.; Kim, J.; Brais, L.K.; Ragon, D.; et al. Real-time genomic characterization of advanced pancreatic cancer to enable precision medicine. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1096–1111.

- Pishvaian, M.J.; Bender, R.J.; Halverson, D.; Rahib, L.; Hendifar, A.E.; Mikhail, S.; Chung, V.; Picozzi, V.J.; Sohal, D.; Blais, E.M.; et al. Molecular profiling of patients with pancreatic cancer: Initial results from the know your tumor initiative. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 5018–5027.

- Pishvaian, M.J.; Blais, E.M.; Brody, J.R.; Lyons, E.; DeArbeloa, P.; Hendifar, A.; Mikhail, S.; Chung, V.; Sahai, V.; Sohal, D.P.S.; et al. Overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer receiving matched therapies following molecular profiling: A retrospective analysis of the Know Your Tumor registry trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 508–518.

- Park, W.; Chen, J.; Chou, J.F.; Varghese, A.M.; Yu, K.H.; Wong, W.; Capanu, M.; Balachandran, V.; McIntyre, C.A.; El Dika, I.; et al. Genomic methods identify homologous recombination deficiency in pancreas adenocarcinoma and optimize treatment selection. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 3239–3247.

- Golan, T.; Hammel, P.; Reni, M.; Van Cutsem, E.; Macarulla, T.; Hall, M.J.; Park, J.O.; Hochhauser, D.; Arnold, D.; Oh, D.Y.; et al. Maintenance olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 317–327.

- O’Reilly, E.M.; Lee, J.W.; Zalupski, M.; Capanu, M.; Park, J.; Golan, T.; Tahover, E.; Lowery, M.A.; Chou, J.F.; Sahai, V.; et al. Randomized, multicenter, phase II trial of gemcitabine and cisplatin with or without veliparib in patients with pancreas adenocarcinoma and a germline BRCA/PALB2 mutation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1378–1388.

- Marabelle, A.; Le, D.T.; Ascierto, P.A.; Di Giacomo, A.M.; De Jesus-Acosta, A.; Delord, J.P.; Geva, R.; Gottfried, M.; Penel, N.; Hansen, A.R.; et al. Efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with noncolorectal high microsatellite instability/mismatch repair-deficient cancer: Results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1–10.

- Feig, C.; Gopinathan, A.; Neesse, A.; Chan, D.S.; Cook, N.; Tuveson, D.A. The pancreas cancer microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 4266–4276.

- Neesse, A.; Bauer, C.A.; Ohlund, D.; Lauth, M.; Buchholz, M.; Michl, P.; Tuveson, D.A.; Gress, T.M. Stromal biology and therapy in pancreatic cancer: Ready for clinical translation? Gut 2019, 68, 159–171.

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Helmink, B.A.; Spencer, C.N.; Reuben, A.; Wargo, J.A. The Influence of the gut microbiome on cancer, immunity, and cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 570–580.

- Sethi, V.; Vitiello, G.A.; Saxena, D.; Miller, G.; Dudeja, V. The Role of the microbiome in immunologic development and its implication for pancreatic cancer immunotherapy. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 2097–2115.e2.

- Riquelme, E.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Montiel, M.; Zoltan, M.; Dong, W.; Quesada, P.; Sahin, I.; Chandra, V.; San Lucas, A.; et al. Tumor microbiome diversity and composition influence pancreatic cancer outcomes. Cell 2019, 178, 795–806.e12.

- Pushalkar, S.; Hundeyin, M.; Daley, D.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Kurz, E.; Mishra, A.; Mohan, N.; Aykut, B.; Usyk, M.; Torres, L.E.; et al. The pancreatic cancer microbiome promotes oncogenesis by induction of innate and adaptive immune suppression. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 403–416.

- Ciocan, D.; Rebours, V.; Voican, C.S.; Wrzosek, L.; Puchois, V.; Cassard, A.M.; Perlemuter, G. Characterization of intestinal microbiota in alcoholic patients with and without alcoholic hepatitis or chronic alcoholic pancreatitis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4822.

- Gaiser, R.A.; Halimi, A.; Alkharaan, H.; Lu, L.; Davanian, H.; Healy, K.; Hugerth, L.W.; Ateeb, Z.; Valente, R.; Fernandez Moro, C.; et al. Enrichment of oral microbiota in early cystic precursors to invasive pancreatic cancer. Gut 2019, 68, 2186–2194.

- Jones, S.; Zhang, X.; Parsons, D.W.; Lin, J.C.; Leary, R.J.; Angenendt, P.; Mankoo, P.; Carter, H.; Kamiyama, H.; Jimeno, A.; et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science 2008, 321, 1801–1806.

- Biankin, A.V.; Waddell, N.; Kassahn, K.S.; Gingras, M.C.; Muthuswamy, L.B.; Johns, A.L.; Miller, D.K.; Wilson, P.J.; Patch, A.M.; Wu, J.; et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature 2012, 491, 399–405.

- Waddell, N.; Pajic, M.; Patch, A.M.; Chang, D.K.; Kassahn, K.S.; Bailey, P.; Johns, A.L.; Miller, D.; Nones, K.; Quek, K.; et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2015, 518, 495–501.

- Bailey, P.; Chang, D.K.; Nones, K.; Johns, A.L.; Patch, A.M.; Gingras, M.C.; Miller, D.K.; Christ, A.N.; Bruxner, T.J.; Quinn, M.C.; et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2016, 531, 47–52.

- Raphael, B.J.; Hruban, R.H.; Aguirre, A.J.; Moffitt, R.A.; Yeh, J.J.; Stewart, C.; Robertson, A.G.; Cherniack, A.D.; Gupta, M.; Getz, G.; et al. Integrated genomic characterization of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 185–203.e13.

- Collisson, E.A.; Sadanandam, A.; Olson, P.; Gibb, W.J.; Truitt, M.; Gu, S.; Cooc, J.; Weinkle, J.; Kim, G.E.; Jakkula, L.; et al. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing responses to therapy. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 500–503.

- Moffitt, R.A.; Marayati, R.; Flate, E.L.; Volmar, K.E.; Loeza, S.G.; Hoadley, K.A.; Rashid, N.U.; Williams, L.A.; Eaton, S.C.; Chung, A.H.; et al. Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor- and stroma-specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1168–1178.

- Puleo, F.; Nicolle, R.; Blum, Y.; Cros, J.; Marisa, L.; Demetter, P.; Quertinmont, E.; Svrcek, M.; Elarouci, N.; Iovanna, J.; et al. Stratification of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas based on tumor and microenvironment features. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1999–2013.e3.

- Maurer, C.; Holmstrom, S.R.; He, J.; Laise, P.; Su, T.; Ahmed, A.; Hibshoosh, H.; Chabot, J.A.; Oberstein, P.E.; Sepulveda, A.R.; et al. Experimental microdissection enables functional harmonisation of pancreatic cancer subtypes. Gut 2019, 68, 1034–1043.

- Kalimuthu, S.N.; Wilson, G.W.; Grant, R.C.; Seto, M.; O’Kane, G.; Vajpeyi, R.; Notta, F.; Gallinger, S.; Chetty, R. Morphological classification of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma that predicts molecular subtypes and correlates with clinical outcome. Gut 2020, 69, 317–328.

- Muckenhuber, A.; Berger, A.K.; Schlitter, A.M.; Steiger, K.; Konukiewitz, B.; Trumpp, A.; Eils, R.; Werner, J.; Friess, H.; Esposito, I.; et al. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma subtyping using the biomarkers hepatocyte nuclear factor-1A and cytokeratin-81 correlates with outcome and treatment response. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 351–359.

- Aung, K.L.; Fischer, S.E.; Denroche, R.E.; Jang, G.H.; Dodd, A.; Creighton, S.; Southwood, B.; Liang, S.B.; Chadwick, D.; Zhang, A.; et al. Genomics-driven precision medicine for advanced pancreatic cancer: Early results from the COMPASS trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1344–1354.

- O’Kane, G.M.; Grunwald, B.T.; Jang, G.H.; Masoomian, M.; Picardo, S.; Grant, R.C.; Denroche, R.E.; Zhang, A.; Wang, Y.; Lam, B.; et al. GATA6 Expression distinguishes classical and basal-like subtypes in advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 4901–4910.

- Martinelli, P.; Carrillo-de Santa Pau, E.; Cox, T.; Sainz, B., Jr.; Dusetti, N.; Greenhalf, W.; Rinaldi, L.; Costello, E.; Ghaneh, P.; Malats, N.; et al. GATA6 regulates EMT and tumour dissemination, and is a marker of response to adjuvant chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Gut 2017, 66, 1665–1676.

- Tiriac, H.; Belleau, P.; Engle, D.D.; Plenker, D.; Deschenes, A.; Somerville, T.D.D.; Froeling, F.E.M.; Burkhart, R.A.; Denroche, R.E.; Jang, G.H.; et al. Organoid profiling identifies common responders to chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1112–1129.

- Adams, C.R.; Htwe, H.H.; Marsh, T.; Wang, A.L.; Montoya, M.L.; Subbaraj, L.; Tward, A.D.; Bardeesy, N.; Perera, R.M. Transcriptional control of subtype switching ensures adaptation and growth of pancreatic cancer. Elife 2019, 8, e45313.

- Somerville, T.D.D.; Xu, Y.; Miyabayashi, K.; Tiriac, H.; Cleary, C.R.; Maia-Silva, D.; Milazzo, J.P.; Tuveson, D.A.; Vakoc, C.R. TP63-mediated enhancer reprogramming drives the squamous subtype of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 1741–1755.e7.

- Kapoor, A.; Yao, W.; Ying, H.; Hua, S.; Liewen, A.; Wang, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, C.J.; Sadanandam, A.; Hu, B.; et al. Yap1 activation enables bypass of oncogenic Kras addiction in pancreatic cancer. Cell 2019, 179, 1239.

- Mueller, S.; Engleitner, T.; Maresch, R.; Zukowska, M.; Lange, S.; Kaltenbacher, T.; Konukiewitz, B.; Ollinger, R.; Zwiebel, M.; Strong, A.; et al. Evolutionary routes and KRAS dosage define pancreatic cancer phenotypes. Nature 2018, 554, 62–68.

- Chan-Seng-Yue, M.; Kim, J.C.; Wilson, G.W.; Ng, K.; Figueroa, E.F.; O’Kane, G.M.; Connor, A.A.; Denroche, R.E.; Grant, R.C.; McLeod, J.; et al. Transcription phenotypes of pancreatic cancer are driven by genomic events during tumor evolution. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 231–240.

- Miyabayashi, K.; Baker, L.A.; Deschenes, A.; Traub, B.; Caligiuri, G.; Plenker, D.; Alagesan, B.; Belleau, P.; Li, S.; Kendall, J.; et al. Intraductal transplantation models of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma reveal progressive transition of molecular subtypes. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1566–1589.

- Guo, W.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, S.; Mei, Z.; Liao, H.; Dong, H.; Wu, K.; Ye, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Tumor microbiome contributes to an aggressive phenotype in the basal-like subtype of pancreatic cancer. Commun. Biol 2021, 4, 1019.

- Ohlund, D.; Handly-Santana, A.; Biffi, G.; Elyada, E.; Almeida, A.S.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; Corbo, V.; Oni, T.E.; Hearn, S.A.; Lee, E.J.; et al. Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 579–596.

- Biffi, G.; Oni, T.E.; Spielman, B.; Hao, Y.; Elyada, E.; Park, Y.; Preall, J.; Tuveson, D.A. IL1-induced JAK/STAT signaling is antagonized by TGFbeta to shape CAF heterogeneity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 282–301.

- Elyada, E.; Bolisetty, M.; Laise, P.; Flynn, W.F.; Courtois, E.T.; Burkhart, R.A.; Teinor, J.A.; Belleau, P.; Biffi, G.; Lucito, M.S.; et al. Cross-species single-cell analysis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma reveals antigen-presenting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 1102–1123.

- Ligorio, M.; Sil, S.; Malagon-Lopez, J.; Nieman, L.T.; Misale, S.; Di Pilato, M.; Ebright, R.Y.; Karabacak, M.N.; Kulkarni, A.S.; Liu, A.; et al. Stromal microenvironment shapes the intratumoral architecture of pancreatic cancer. Cell 2019, 178, 160–175.e27.

- Nicolle, R.; Blum, Y.; Marisa, L.; Loncle, C.; Gayet, O.; Moutardier, V.; Turrini, O.; Giovannini, M.; Bian, B.; Bigonnet, M.; et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma therapeutic targets revealed by tumor-stroma cross-talk analyses in patient-derived xenografts. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 2458–2470.

- Sahin, I.H.; Askan, G.; Hu, Z.I.; O’Reilly, E.M. Immunotherapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: An emerging entity? Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 2950–2961.

- Uzunparmak, B.; Sahin, I.H. Pancreatic cancer microenvironment: A current dilemma. Clin. Transl. Med. 2019, 8, 2.

- Stromnes, I.M.; Hulbert, A.; Pierce, R.H.; Greenberg, P.D.; Hingorani, S.R. T-cell localization, activation, and clonal expansion in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017, 5, 978–991.

- Balli, D.; Rech, A.J.; Stanger, B.Z.; Vonderheide, R.H. Immune cytolytic activity stratifies molecular subsets of human pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 3129–3138.

- Bailey, P.; Chang, D.K.; Forget, M.A.; Lucas, F.A.; Alvarez, H.A.; Haymaker, C.; Chattopadhyay, C.; Kim, S.H.; Ekmekcioglu, S.; Grimm, E.A.; et al. Exploiting the neoantigen landscape for immunotherapy of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35848.

- Gunderson, A.J.; Kaneda, M.M.; Tsujikawa, T.; Nguyen, A.V.; Affara, N.I.; Ruffell, B.; Gorjestani, S.; Liudahl, S.M.; Truitt, M.; Olson, P.; et al. Bruton tyrosine kinase-dependent immune cell cross-talk drives pancreas cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 270–285.

- Li, J.; Byrne, K.T.; Yan, F.; Yamazoe, T.; Chen, Z.; Baslan, T.; Richman, L.P.; Lin, J.H.; Sun, Y.H.; Rech, A.J.; et al. Tumor cell-intrinsic factors underlie heterogeneity of immune cell infiltration and response to immunotherapy. Immunity 2018, 49, 178–193.e7.

- Balachandran, V.P.; Luksza, M.; Zhao, J.N.; Makarov, V.; Moral, J.A.; Remark, R.; Herbst, B.; Askan, G.; Bhanot, U.; Senbabaoglu, Y.; et al. Identification of unique neoantigen qualities in long-term survivors of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2017, 551, 512–516.

- Feig, C.; Jones, J.O.; Kraman, M.; Wells, R.J.; Deonarine, A.; Chan, D.S.; Connell, C.M.; Roberts, E.W.; Zhao, Q.; Caballero, O.L.; et al. Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20212–20217.

- Chen, P.L.; Roh, W.; Reuben, A.; Cooper, Z.A.; Spencer, C.N.; Prieto, P.A.; Miller, J.P.; Bassett, R.L.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Wani, K.; et al. Analysis of immune signatures in longitudinal tumor samples yields insight into biomarkers of response and mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 827–837.

- Kortlever, R.M.; Sodir, N.M.; Wilson, C.H.; Burkhart, D.L.; Pellegrinet, L.; Brown Swigart, L.; Littlewood, T.D.; Evan, G.I. Myc cooperates with Ras by programming inflammation and immune suppression. Cell 2017, 171, 1301–1315.e14.

- Peng, D.; Kryczek, I.; Nagarsheth, N.; Zhao, L.; Wei, S.; Wang, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, E.; Vatan, L.; Szeliga, W.; et al. Epigenetic silencing of TH1-type chemokines shapes tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nature 2015, 527, 249–253.

- Spranger, S.; Bao, R.; Gajewski, T.F. Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2015, 523, 231–235.

- Wang, G.; Lu, X.; Dey, P.; Deng, P.; Wu, C.C.; Jiang, S.; Fang, Z.; Zhao, K.; Konaparthi, R.; Hua, S.; et al. Targeting YAP-dependent MDSC infiltration impairs tumor progression. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 80–95.

- Welte, T.; Kim, I.S.; Tian, L.; Gao, X.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Holdman, X.B.; Herschkowitz, J.I.; Pond, A.; Xie, G.; et al. Oncogenic mTOR signalling recruits myeloid-derived suppressor cells to promote tumour initiation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 632–644.

- Le, D.T.; Durham, J.N.; Smith, K.N.; Wang, H.; Bartlett, B.R.; Aulakh, L.K.; Lu, S.; Kemberling, H.; Wilt, C.; Luber, B.S.; et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 2017, 357, 409–413.

- Zhu, Y.; Knolhoff, B.L.; Meyer, M.A.; Nywening, T.M.; West, B.L.; Luo, J.; Wang-Gillam, A.; Goedegebuure, S.P.; Linehan, D.C.; DeNardo, D.G. CSF1/CSF1R blockade reprograms tumor-infiltrating macrophages and improves response to T-cell checkpoint immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer models. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 5057–5069.

- Candido, J.B.; Morton, J.P.; Bailey, P.; Campbell, A.D.; Karim, S.A.; Jamieson, T.; Lapienyte, L.; Gopinathan, A.; Clark, W.; McGhee, E.J.; et al. CSF1R(+) macrophages sustain pancreatic tumor growth through T Cell suppression and maintenance of key gene programs that define the squamous subtype. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 1448–1460.

- Nywening, T.M.; Belt, B.A.; Cullinan, D.R.; Panni, R.Z.; Han, B.J.; Sanford, D.E.; Jacobs, R.C.; Ye, J.; Patel, A.A.; Gillanders, W.E.; et al. Targeting both tumour-associated CXCR2(+) neutrophils and CCR2(+) macrophages disrupts myeloid recruitment and improves chemotherapeutic responses in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gut 2018, 67, 1112–1123.

- Steele, C.W.; Karim, S.A.; Leach, J.D.G.; Bailey, P.; Upstill-Goddard, R.; Rishi, L.; Foth, M.; Bryson, S.; McDaid, K.; Wilson, Z.; et al. CXCR2 inhibition profoundly suppresses metastases and augments immunotherapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 832–845.

- Aykut, B.; Pushalkar, S.; Chen, R.; Li, Q.; Abengozar, R.; Kim, J.I.; Shadaloey, S.A.; Wu, D.; Preiss, P.; Verma, N.; et al. The fungal mycobiome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via activation of MBL. Nature 2019, 574, 264–267.

- Alam, A.; Levanduski, E.; Denz, P.; Villavicencio, H.S.; Bhatta, M.; Alhorebi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gomez, E.C.; Morreale, B.; Senchanthisai, S.; et al. Fungal mycobiome drives IL-33 secretion and type 2 immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 153–167.e11.

- Zambirinis, C.P.; Levie, E.; Nguy, S.; Avanzi, A.; Barilla, R.; Xu, Y.; Seifert, L.; Daley, D.; Greco, S.H.; Deutsch, M.; et al. TLR9 ligation in pancreatic stellate cells promotes tumorigenesis. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 2077–2094.

- Ochi, A.; Nguyen, A.H.; Bedrosian, A.S.; Mushlin, H.M.; Zarbakhsh, S.; Barilla, R.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Fallon, N.C.; Rehman, A.; Pylayeva-Gupta, Y.; et al. MyD88 inhibition amplifies dendritic cell capacity to promote pancreatic carcinogenesis via Th2 cells. J. Exp. Med. 2012, 209, 1671–1687.

- Yoshimoto, S.; Loo, T.M.; Atarashi, K.; Kanda, H.; Sato, S.; Oyadomari, S.; Iwakura, Y.; Oshima, K.; Morita, H.; Hattori, M.; et al. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature 2013, 499, 97–101.

- Hezaveh, K.; Shinde, R.S.; Klotgen, A.; Halaby, M.J.; Lamorte, S.; Ciudad, M.T.; Quevedo, R.; Neufeld, L.; Liu, Z.Q.; Jin, R.; et al. Tryptophan-derived microbial metabolites activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in tumor-associated macrophages to suppress anti-tumor immunity. Immunity 2022, 55, 324–340.e328.

- Geller, L.T.; Barzily-Rokni, M.; Danino, T.; Jonas, O.H.; Shental, N.; Nejman, D.; Gavert, N.; Zwang, Y.; Cooper, Z.A.; Shee, K.; et al. Potential role of intratumor bacteria in mediating tumor resistance to the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine. Science 2017, 357, 1156–1160.

- Hu, Z.I.; Shia, J.; Stadler, Z.K.; Varghese, A.M.; Capanu, M.; Salo-Mullen, E.; Lowery, M.A.; Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Mandelker, D.; Yu, K.H.; et al. Evaluating mismatch repair deficiency in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Challenges and recommendations. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1326–1336.

- Latham, A.; Srinivasan, P.; Kemel, Y.; Shia, J.; Bandlamudi, C.; Mandelker, D.; Middha, S.; Hechtman, J.; Zehir, A.; Dubard-Gault, M.; et al. Microsatellite instability is associated with the presence of Lynch syndrome pan-cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 286–295.

- Sahin, I.H.; Akce, M.; Alese, O.; Shaib, W.; Lesinski, G.B.; El-Rayes, B.; Wu, C. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of MSI-H/MMR-D colorectal cancer and a perspective on resistance mechanisms. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 809–818.

- Grant, R.C.; Denroche, R.; Jang, G.H.; Nowak, K.M.; Zhang, A.; Borgida, A.; Holter, S.; Topham, J.T.; Wilson, J.; Dodd, A.; et al. Clinical and genomic characterisation of mismatch repair deficient pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Gut 2020, 70, 1894–1903.

- Balachandran, V.P.; Beatty, G.L.; Dougan, S.K. Broadening the impact of immunotherapy to pancreatic cancer: Challenges and opportunities. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 2056–2072.

- Naing, A.; Infante, J.R.; Papadopoulos, K.P.; Chan, I.H.; Shen, C.; Ratti, N.P.; Rojo, B.; Autio, K.A.; Wong, D.J.; Patel, M.R.; et al. PEGylated IL-10 (Pegilodecakin) induces systemic immune activation, CD8(+) T cell invigoration and polyclonal T cell expansion in cancer patients. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 775–791.e3.

- Le, D.T.; Lutz, E.; Uram, J.N.; Sugar, E.A.; Onners, B.; Solt, S.; Zheng, L.; Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Donehower, R.C.; Jaffee, E.M.; et al. Evaluation of ipilimumab in combination with allogeneic pancreatic tumor cells transfected with a GM-CSF gene in previously treated pancreatic cancer. J. Immunother. 2013, 36, 382–389.

- Beatty, G.L.; O’Hara, M.H.; Lacey, S.F.; Torigian, D.A.; Nazimuddin, F.; Chen, F.; Kulikovskaya, I.M.; Soulen, M.C.; McGarvey, M.; Nelson, A.M.; et al. Activity of mesothelin-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells against pancreatic carcinoma metastases in a phase 1 trial. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 29–32.

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillere, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97.

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Spencer, C.N.; Nezi, L.; Reuben, A.; Andrews, M.C.; Karpinets, T.V.; Prieto, P.A.; Vicente, D.; Hoffman, K.; Wei, S.C.; et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 97–103.

- Matson, V.; Fessler, J.; Bao, R.; Chongsuwat, T.; Zha, Y.; Alegre, M.L.; Luke, J.J.; Gajewski, T.F. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 104–108.

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ridaura, V.K.; Faith, J.J.; Rey, F.E.; Knight, R.; Gordon, J.I. The effect of diet on the human gut microbiome: A metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2009, 1, 6ra14.

- Nguyen, T.L.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Liston, A.; Raes, J. How informative is the mouse for human gut microbiota research? Dis. Models Mech. 2015, 8, 1–16.

- De Filippo, C.; Cavalieri, D.; Di Paola, M.; Ramazzotti, M.; Poullet, J.B.; Massart, S.; Collini, S.; Pieraccini, G.; Lionetti, P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14691–14696.

- Yatsunenko, T.; Rey, F.E.; Manary, M.J.; Trehan, I.; Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Contreras, M.; Magris, M.; Hidalgo, G.; Baldassano, R.N.; Anokhin, A.P.; et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 2012, 486, 222–227.

- Rothschild, D.; Weissbrod, O.; Barkan, E.; Kurilshikov, A.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Costea, P.I.; Godneva, A.; Kalka, I.N.; Bar, N.; et al. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature 2018, 555, 210–215.

- Vangay, P.; Johnson, A.J.; Ward, T.L.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Shields-Cutler, R.R.; Hillmann, B.M.; Lucas, S.K.; Beura, L.K.; Thompson, E.A.; Till, L.M.; et al. US immigration westernizes the human gut microbiome. Cell 2018, 175, 962–972.e10.

- Ericsson, A.C.; Davis, J.W.; Spollen, W.; Bivens, N.; Givan, S.; Hagan, C.E.; McIntosh, M.; Franklin, C.L. Effects of vendor and genetic background on the composition of the fecal microbiota of inbred mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116704.

- Villarino, N.F.; LeCleir, G.R.; Denny, J.E.; Dearth, S.P.; Harding, C.L.; Sloan, S.S.; Gribble, J.L.; Campagna, S.R.; Wilhelm, S.W.; Schmidt, N.W. Composition of the gut microbiota modulates the severity of malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2235–2240.

- Ochi, A.; Graffeo, C.S.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Rehman, A.; Hackman, M.; Fallon, N.; Barilla, R.M.; Henning, J.R.; Jamal, M.; Rao, R.; et al. Toll-like receptor 7 regulates pancreatic carcinogenesis in mice and humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 4118–4129.

- Daley, D.; Mani, V.R.; Mohan, N.; Akkad, N.; Ochi, A.; Heindel, D.W.; Lee, K.B.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Pandian, G.S.B.; Savadkar, S.; et al. Dectin 1 activation on macrophages by galectin 9 promotes pancreatic carcinoma and peritumoral immune tolerance. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 556–567.

- Daley, D.; Mani, V.R.; Mohan, N.; Akkad, N.; Pandian, G.; Savadkar, S.; Lee, K.B.; Torres-Hernandez, A.; Aykut, B.; Diskin, B.; et al. NLRP3 signaling drives macrophage-induced adaptive immune suppression in pancreatic carcinoma. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 1711–1724.

- Thomas, R.M.; Gharaibeh, R.Z.; Gauthier, J.; Beveridge, M.; Pope, J.L.; Guijarro, M.V.; Yu, Q.; He, Z.; Ohland, C.; Newsome, R.; et al. Intestinal microbiota enhances pancreatic carcinogenesis in preclinical models. Carcinogenesis 2018, 39, 1068–1078.

- Sethi, V.; Kurtom, S.; Tarique, M.; Lavania, S.; Malchiodi, Z.; Hellmund, L.; Zhang, L.; Sharma, U.; Giri, B.; Garg, B.; et al. Gut microbiota promotes tumor growth in mice by modulating immune response. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 33–37.e6.

- Pinato, D.J.; Howlett, S.; Ottaviani, D.; Urus, H.; Patel, A.; Mineo, T.; Brock, C.; Power, D.; Hatcher, O.; Falconer, A.; et al. Association of prior antibiotic treatment with survival and response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1774–1778.

- Elkrief, A.; El Raichani, L.; Richard, C.; Messaoudene, M.; Belkaid, W.; Malo, J.; Belanger, K.; Miller, W.; Jamal, R.; Letarte, N.; et al. Antibiotics are associated with decreased progression-free survival of advanced melanoma patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, e1568812.

- Huemer, F.; Rinnerthaler, G.; Westphal, T.; Hackl, H.; Hutarew, G.; Gampenrieder, S.P.; Weiss, L.; Greil, R. Impact of antibiotic treatment on immune-checkpoint blockade efficacy in advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 16512–16520.

- Sivan, A.; Corrales, L.; Hubert, N.; Williams, J.B.; Aquino-Michaels, K.; Earley, Z.M.; Benyamin, F.W.; Lei, Y.M.; Jabri, B.; Alegre, M.L.; et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science 2015, 350, 1084–1089.

- Vetizou, M.; Pitt, J.M.; Daillere, R.; Lepage, P.; Waldschmitt, N.; Flament, C.; Rusakiewicz, S.; Routy, B.; Roberti, M.P.; Duong, C.P.; et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science 2015, 350, 1079–1084.

- Chowdhury, S.; Castro, S.; Coker, C.; Hinchliffe, T.E.; Arpaia, N.; Danino, T. Programmable bacteria induce durable tumor regression and systemic antitumor immunity. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1057–1063.

More

Information

Subjects:

Oncology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Revisions:

4 times

(View History)

Update Date:

20 Oct 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No