| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ali Arshad | -- | 2682 | 2022-09-06 15:43:16 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | -7 word(s) | 2675 | 2022-09-07 03:12:07 | | | | |

| 3 | Amina Yu | Meta information modification | 2675 | 2022-09-08 08:27:58 | | |

Video Upload Options

Neural network computational methods have evolved over the past half-century. In 1943, McCulloch and Pitts designed the first model, recognized as the linear threshold gate. Hebbian developed the Hebbian learning rule approach for training the neural network. However, would the Hebbian rule remain productive when all the input patterns became orthogonal? The existence of orthogonality in input vectors is a crucial component for this rule to execute effectively. To meet this requirement, a much more productive learning rule, known as the Delta rule, was established. Whereas the delta rule poses issues with the learning principles outlined above, backpropagation has developed as a more complicated learning approach. Backpropagation could learn an infinite layered structure and estimate any commutative function. A feed-forward neural network is most often trained using backpropagation (FFNN).

1. Novel Pooling Methods

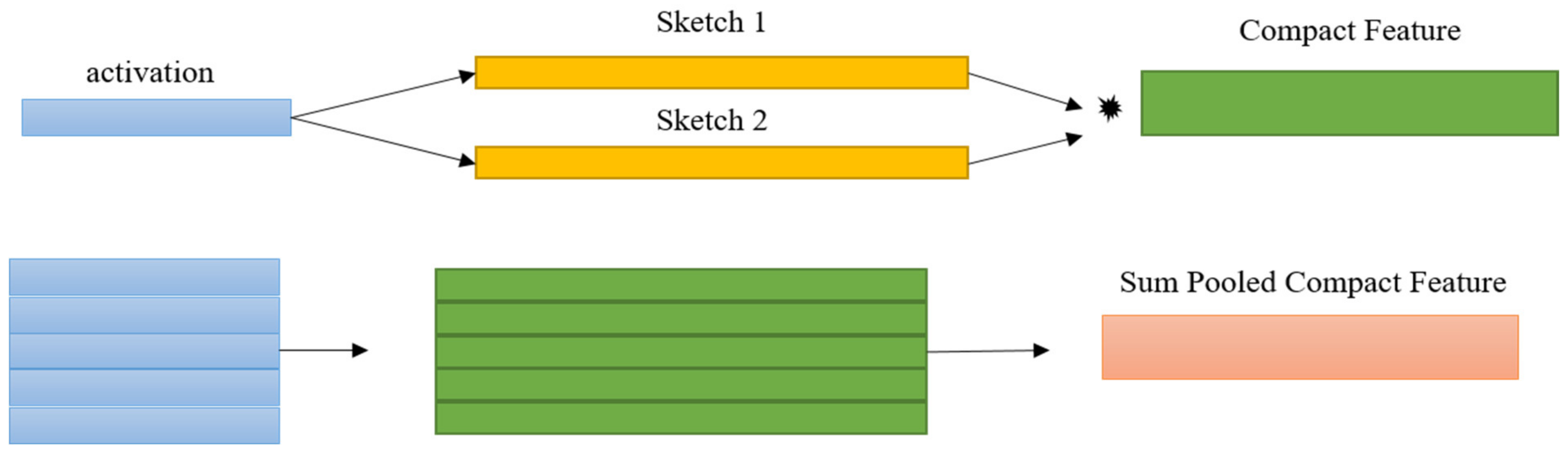

1.1 Compact Bilinear Pooling

1.2. Spectral Pooling

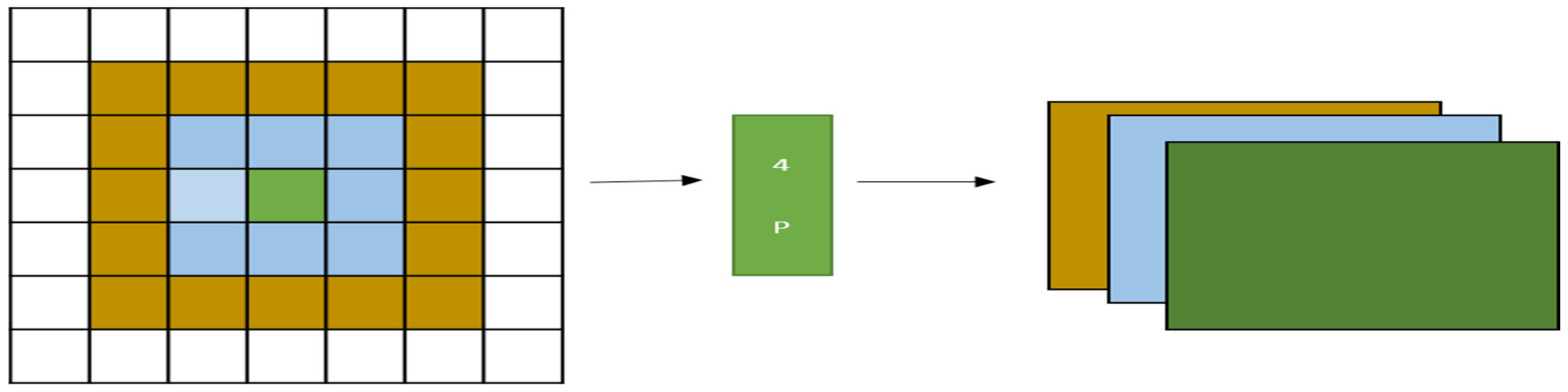

1.3. Per Pixel Pyramid Pooling

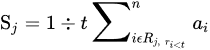

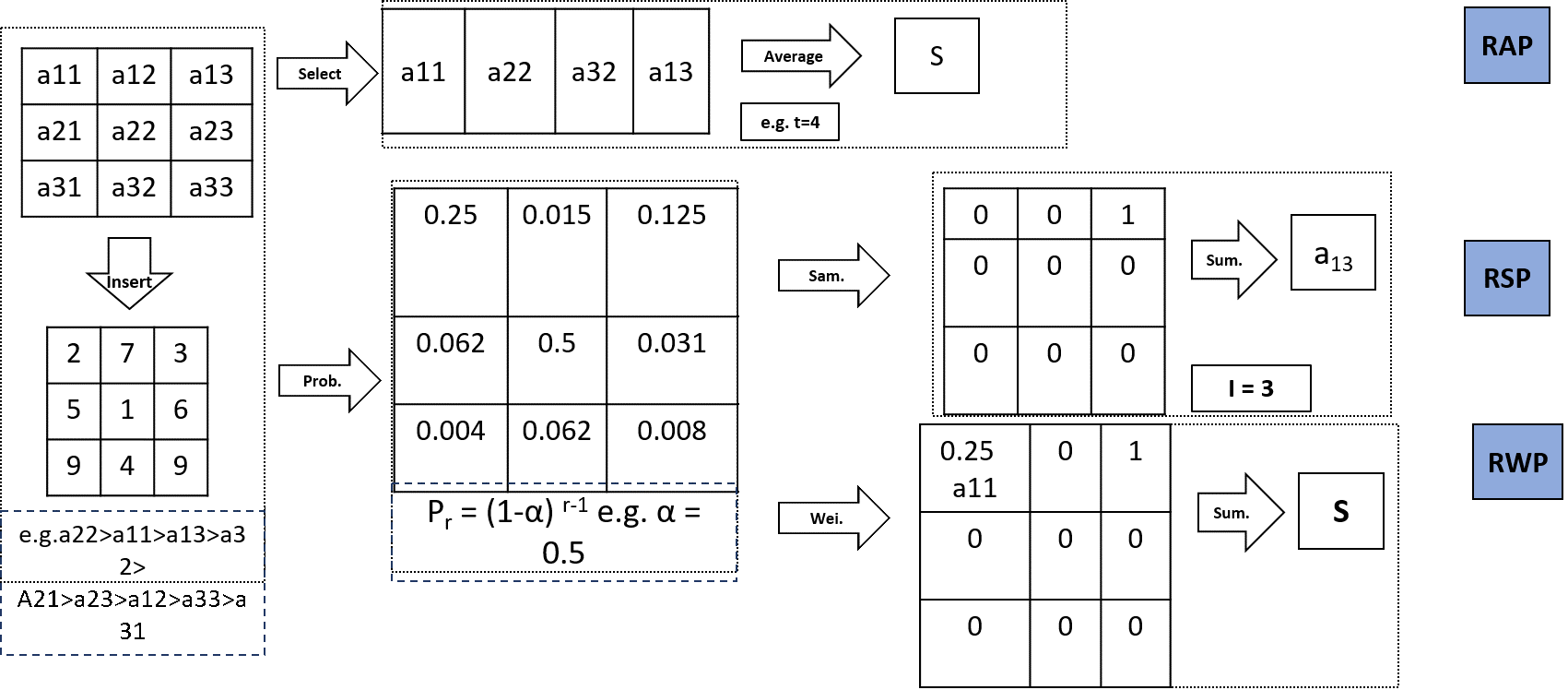

1.4. Rank-Based Average Pooling

1.5. Max-Out Fractional Pooling

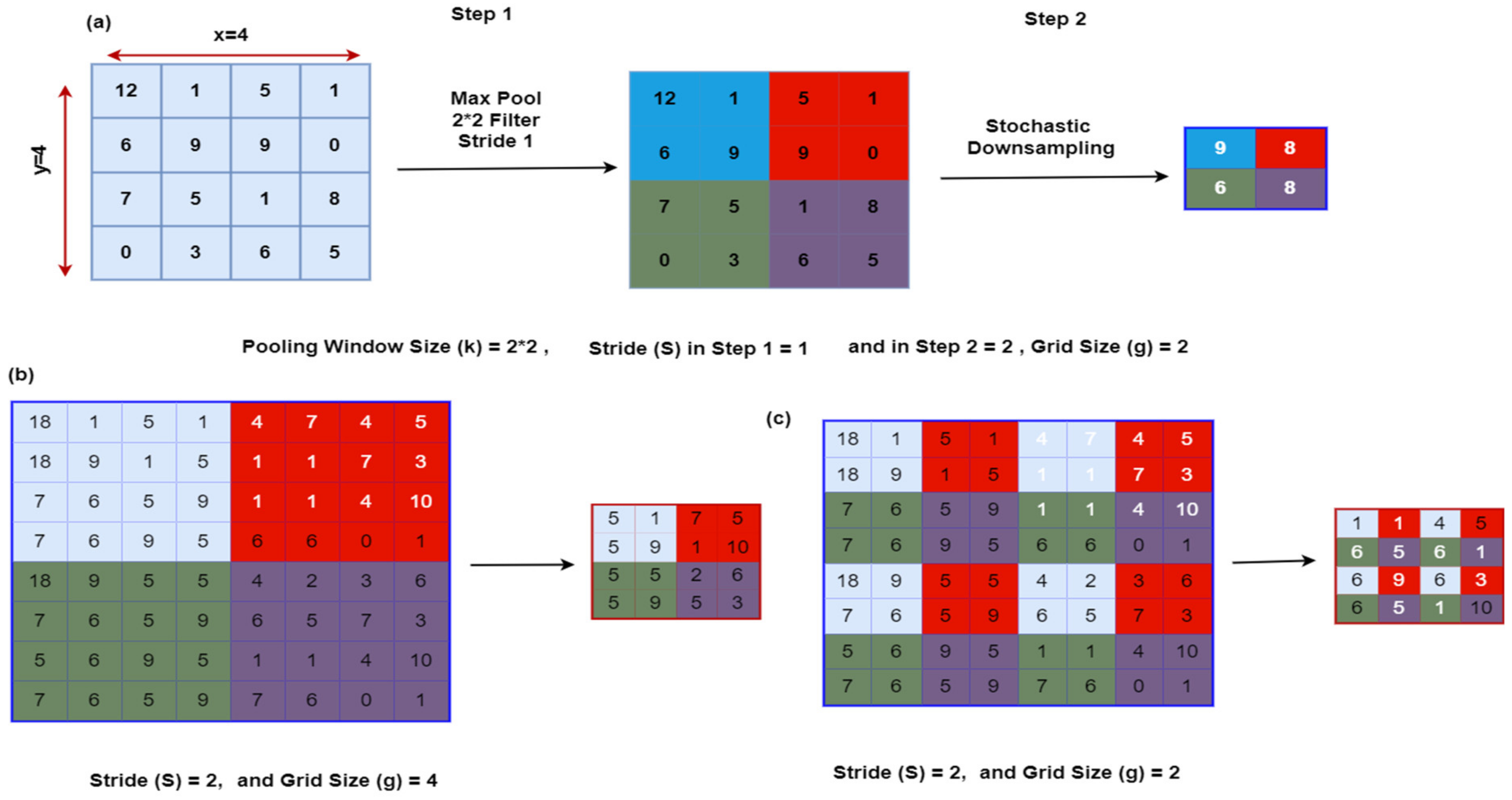

1.6. S3Pooling

1.7. Methods to Preserve Critical Information When Pooling

2. Advantages and Disadvantages of Pooling Approaches

| Type of Pooling | Advantages | Drawbacks | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Pooling |

|

|

[16][17] |

| Average Pooling |

|

|

[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][16][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29] |

| Gated Max Average |

|

|

[19] |

| Mixed Max Average |

|

|

[20] |

| Pyramid Pooling |

|

|

[21] |

| Stochastic Pooling |

|

|

[22] |

| Tree Pooling |

|

|

[19][30] |

| Fractional Max Pooling |

|

|

[31] |

| S3Pool |

|

|

[6] |

| Rank-Based Average Pooling |

|

|

[23] |

Performance Evaluation of Popular Pooling Methods

| Pooling Methods | Architecture | Activation Function | Error Rate of Different Datasets | Accuracy | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNIST | CIFAR-10 | CIFAR-100 | |||||

| Gated Method | 6 Convolutional Layers | RELU | 0.29 | 7.90 | 33.22 | 88% (Rotation Angle) | [32] |

| Mixed Pooling | 6 Convolutional Layers | RELU | 0.30 | 8.01 | 33.35 | 90% (Translation Angle) | |

| Max Pooling | 6 Convolutional Layers | RELU | 0.32 | 7.68 | 32.41 | 93.75% (Scale Multiplier) | |

| Max + Tree Pooling | 6 Convolutional Layers | RELU | 0.39 | 9.28 | 34.75 | ||

| Mixed Pooling | 6 Convolutional Layers (Without data Augmentation) | RELU | 10.41 | 12.61 | 37.20 | 91.5% | [33] |

| Stochastic Pooling | 3 Convolutional Layers | RELU | 0.47 | 15.26 | 42.58 | --------- | [31] |

| Average Pooling | 6 Convolutional Layers | RELU | 0.83 | 19.38 | 47.18 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Average Pooling (RAP) | 3 Convolutional Layers | RELU | 0.56 | 18.28 | 46.24 | --------- | [6] |

| Rank-Based Weighted Pooling (RWP) | 3 Convolutional Layers | RELU | 0.56 | 19.28 | 48.54 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Stochastic Pooling (RSP) | 3 Convolutional Layers | RELU | 0.59 | 17.85 | 45.48 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Average Pooling (RAP) | 3 Convolutional Layers | RELU (Parametric) | 0.56 | 18.58 | 45.86 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Weighted Pooling (RWP) | 3 Convolutional Layers | RELU (Parametric) | 0.53 | 18.96 | 47.09 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Stochastic pooling (RSP) | 3 Convolutional Layers | RELU (Parametric) | 0.42 | 14.26 | 44.97 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Average Pooling (RAP) | 3 Convolutional Layers | Leaky RELU | 0.58 | 17.97 | 45.64 | ||

| Rank-Based Weighted Pooling (RWP) | 3 Convolutional Layers | Leaky RELU | 0.56 | 19.86 | 48.26 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Stochastic Pooling (RSP) | 3 Convolutional Layers | Leaky RELU | 0.47 | 13.48 | 43.39 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Average Pooling (RAP) | Network in Network (NIN) | Leaky RELU | --------- | 9.48 | 32.18 | --------- | [6] |

| Rank-Based Weighted Pooling (RWP) | Network in Network (NIN) | Leaky RELU | --------- | 9.34 | 32.47 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Stochastic Pooling (RSP) | Network in Network (NIN) | Leaky RELU | --------- | 9.84 | 32.16 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Average Pooling (RAP) | Network in Network (NIN) | RELU | --------- | 9.84 | 34.85 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Weighted Pooling (RWP) | Network in Network (NIN) | RELU | --------- | 10.62 | 35.62 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Stochastic Pooling (RSP) | Network in Network (NIN) | RELU | --------- | 9.48 | 36.18 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Average Pooling (RAP) | Network in Network (NIN) | RELU (Parametric) | --------- | 8.75 | 34.86 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Weighted Pooling (RWP) | Network in Network (NIN) | RELU (Parametric) | --------- | 8.94 | 37.48 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Stochastic Pooling (RSP) | Network in Network (NIN) | RELU (Parametric) | --------- | 8.62 | 34.36 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Average Pooling (RAP) (Includes Data Augmentation) | Network in Network (NIN) | RELU | --------- | 8.67 | 30.48 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Weighted Pooling (RWP) (Includes Data Augmentation) | Network in Network (NIN) | Leaky RELU | --------- | 8.58 | 30.41 | --------- | |

| Rank-Based Stochastic Pooling (RSP) (Includes Data Augmentation) | Network in Network (NIN) | RELU (Parametric) | --------- | 7.74 | 33.67 | --------- | |

| --------- | Network in Network | RELU | 0.49 | 10.74 | 35.86 | --------- | |

| --------- | Supervised Network | RELU | --------- | 9.55 | 34.24 | --------- | |

| --------- | Max out Network | RELU | 0.47 | 11.48 | --------- | --------- | |

| Mixed Pooling | Network in Network (NIN) | RELU | 16.01 | 8.80 | 35.68 | 92.5% | [17] |

| VGG (GOFs Learned Filter) | RELU | 10.08 | 6.23 | 28.64 | |||

| Fused Random Pooling | 10 Convolutional Layers | RELU | --------- | 4.15 | 17.96 | 87.3% | [1] |

| Fractional Max Pooling | 11 Convolutional Layers | Leaky RELU | 0.50 | --------- | 26.49 | [2] | |

| Fractional Max Pooling | Convolutional Layer Network (Sparse) | Leaky RELU | 0.23 | 3.48 | 26.89 | ||

| S3pooling | Network in Network (NIN) (Addition to Dropout) | RELU | --------- | 7.70 | 30.98 | 92.3% | [8] |

| S3pooling | Network in Network (NIN) (Addition to Dropout) | RELU | --------- | 9.84 | 32.48 | ||

| S3pooling | ResNet | RELU | --------- | 7.08 | 29.38 | 84.5% | [30] |

| S3pooling (Flip + Crop) |

ResNet | RELU | --------- | 7.74 | 30.86 | ||

| S3pooling (Flip + Crop) |

CNN With Data Augmentation | RELU | --------- | 7.35 | --------- | ||

| S3pooling (Flip + Crop) |

CNN in Absence of Data Augmenting | RELU | --------- | 9.80 | 32.71 | ||

| Wavelet Pooling | Network in Network | RELU | --------- | 10.41 | 35.70 | 81.04% (CIFAR-100) | [34] |

| ALL-CNN | --------- | 9.09 | --------- | ||||

| ResNet | --------- | 13.76 | 27.30 | 96.87% (CIFAR-10) | |||

| Dense Net | --------- | 7.00 | 27.95 | ||||

| AlphaMaxDenseNet | --------- | 6.56 | 27.45 | ||||

| Temporal Pooling | Global Pooling Layer | Softmax | --------- | --------- | --------- | 91.5% | [35] |

| Spectral Pooling | Attention-Based CNN 2 Convolutional Layers | RELU | 0.605 | 8.87 | --------- | They mentioned improved accuracy but did not mentioned percentage. | [36] |

| Mixed Pooling | 3 Convolutional Layers (Without Data Augmentation) | MBA (Multi Bias Nonlinear Activation) | ------ | 6.75 | 26.14 | [37] | |

| Mixed Pooling | 3 Convolutional Layers (With Data Augmentation) | ------ | 5.37 | 24.2 | |||

| Wavelet Pooling | 3 Convolutional Layers | RELU | ------ | ------ | ------ | 99% (MNIST)74.42 (CIFAR-10)80.28 (CIFAR-100) | [38] |

References

- Yu, T.; Li, X.; Li, P. Fast and compact bilinear pooling by shifted random Maclaurin. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 3243–3251.

- Abouelaziz, I.; Chetouani, A.; El Hassouni, M.; Latecki, L.J.; Cherifi, H. No-reference mesh visual quality assessment via ensemble of convolutional neural networks and compact multi-linear pooling. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 100, 107174.

- Rippel, O.; Snoek, J.; Adams, R.P. Spectral representations for convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28.

- Revaud, J.; Leroy, V.; Weinzaepfel, P.; Chidlovskii, B. PUMP: Pyramidal and Uniqueness Matching Priors for Unsupervised Learning of Local Descriptors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–23 June 2022; pp. 3926–3936.

- Bera, S.; Shrivastava, V.K. Effect of pooling strategy on convolutional neural network for classification of hyperspectral remote sensing images. IET Image Process. 2020, 14, 480–486.

- Shi, Z.; Ye, Y.; Wu, Y. Rank-based pooling for deep convolutional neural networks. Neural Netw. 2016, 83, 21–31.

- Graham, B. Fractional max-pooling. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6071.

- Zhai, S.; Wu, H.; Kumar, A.; Cheng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Feris, R. S3pool: Pooling with stochastic spatial sampling. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July; pp. 4970–4978.

- Pan, X.; Wang, X.; Tian, B.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Guizani, M. Machine-learning-aided optical fiber communication system. IEEE Netw. 2021, 35, 136–142.

- Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Guo, R.; Yang, J.; Yue, J.; Wang, Y. A high-precision detection method of hydroponic lettuce seedlings status based on improved Faster RCNN. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 182, 106054.

- Saeedan, F.; Weber, N.; Goesele, M.; Roth, S. Detail-preserving pooling in deep networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2018, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 9108–9116.

- Gao, Z.; Wang, L.; Wu, G. Lip: Local importance-based pooling. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3355–3364.

- Saha, O.; Kusupati, A.; Simhadri, H.V.; Varma, M.; Jain, P. RNNPool: Efficient non-linear pooling for RAM constrained inference. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 20473–20484.

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Shi, Y. RP-Unet: A Unet-based network with RNNPool enables computation-efficient polyp segmentation. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Workshop on Pattern Recognition, Beijing, China, 25–28 June 2021; Volume 11913, p. 1191302.

- Wang, S.H.; Khan, M.A.; Zhang, Y.D. VISPNN: VGG-inspired stochastic pooling neural network. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 70, 3081.

- Zeiler, M.D.; Fergus, R. Visualizing and understanding convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 818–833.

- Anwar, S.M.; Majid, M.; Qayyum, A.; Awais, M.; Alnowami, M.; Khan, M.K. Medical image analysis using convolutional neural networks: A review. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 1–3.

- Ni, R.; Goldblum, M.; Sharaf, A.; Kong, K.; Goldstein, T. Data augmentation for meta-learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR), Virtual Event, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8152–8161.

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, M.; Gu, Z.; Pan, G. Overfitting remedy by sparsifying regularization on fully-connected layers of CNNs. Neurocomputing 2019, 328, 69–74.

- Chen, Y.; Ming, D.; Lv, X. Superpixel based land cover classification of VHR satellite image combining multi-scale CNN and scale parameter estimation. Earth Sci. Inform. 2019, 12, 341–363.

- Zhang, W.; Shi, P.; Li, M.; Han, D. A novel stochastic resonance model based on bistable stochastic pooling network and its application. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 145, 110800.

- Grauman, K.; Darrell, T. The pyramid match kernel: Discriminative classification with sets of image features. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV’05), Beijing, China, 17–21 October 2005; Volume 2, pp. 1458–1465.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial pyramid pooling in deep convolutional networks for visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 37, 1904–1916.

- Bekkers, E.J. B-spline cnns on lie groups. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.12057.

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2014, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587.

- Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Cao, J.; Wang, Y. Data-driven based tiny-YOLOv3 method for front vehicle detection inducing SPP-net. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 110227–110236.

- Guo, F.; Wang, Y.; Qian, Y. Computer vision-based approach for smart traffic condition assessment at the railroad grade crossing. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 51, 101456.

- Mumuni, A.; Mumuni, F. CNN architectures for geometric transformation-invariant feature representation in computer vision: A review. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 1–23.

- Cao, Z.; Xu, X.; Hu, B.; Zhou, M. Rapid detection of blind roads and crosswalks by using a lightweight semantic segmentation network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 22, 6188–6197.

- Benkaddour, M.K. CNN based features extraction for age estimation and gender classification. Informatica 2021, 45.

- Zeiler, M.D.; Fergus, R. Stochastic pooling for regularization of deep convolutional neural networks. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1301.3557.

- Lee, C.Y.; Gallagher, P.W.; Tu, Z. Generalizing pooling functions in convolutional neural networks: Mixed, gated, and tree. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Cadiz, Spain, 9–11 May 2016; pp. 464–472.

- Bello, M.; Nápoles, G.; Sánchez, R.; Bello, R.; Vanhoof, K. Deep neural network to extract high-level features and labels in multi-label classification problems. Neurocomputing 2020, 413, 259–270.

- Akhtar, N.; Ragavendran, U. Interpretation of intelligence in CNN-pooling processes: A methodological survey. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 879–898.

- Lee, D.; Lee, S.; Yu, H. Learnable dynamic temporal pooling for time series classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2021, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 8288–8296.

- Zhang, H.; Ma, J. Hartley spectral pooling for deep learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04028.

- Li, H.; Ouyang, W.; Wang, X. Multi-bias non-linear activation in deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning 2016, New York City, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016; pp. 221–229.

- Williams, T.; Li, R. Wavelet pooling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018.