Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Luis Puig | -- | 1867 | 2022-09-05 09:58:42 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1867 | 2022-09-06 09:48:39 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | + 2 word(s) | 1869 | 2022-09-06 09:49:24 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Iznardo, H.; Puig, L. The interleukin-1 Family Cytokines, Receptors and Co-Receptors. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26867 (accessed on 03 March 2026).

Iznardo H, Puig L. The interleukin-1 Family Cytokines, Receptors and Co-Receptors. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26867. Accessed March 03, 2026.

Iznardo, Helena, Luís Puig. "The interleukin-1 Family Cytokines, Receptors and Co-Receptors" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26867 (accessed March 03, 2026).

Iznardo, H., & Puig, L. (2022, September 05). The interleukin-1 Family Cytokines, Receptors and Co-Receptors. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26867

Iznardo, Helena and Luís Puig. "The interleukin-1 Family Cytokines, Receptors and Co-Receptors." Encyclopedia. Web. 05 September, 2022.

Copy Citation

The interleukin-1 (IL-1) family is involved in the correct functioning and regulation of the innate immune system, linking innate and adaptative immune responses. This complex family is composed by several cytokines, receptors, and co-receptors, all working in a balanced way to maintain homeostasis.

IL-36

IL-36R

IL-1

IL-33

pathogenesis

1. Introduction

The interleukin-1 (IL-1) family members are central players of the immune system. They are especially involved in the regulation of innate immune responses, maintaining endogenous hemostasis, and linking innate and adaptive responses. Several cytokines, receptors, and accessory proteins constitute this complex family; their activation and expression are balanced by different regulatory mechanisms, and their disturbance results in pathologic inflammatory responses. Disruption of IL-1-related pathways is involved in several inflammatory dermatoses such as psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), atopic dermatitis (AD), as well as several neutrophilic dermatoses.

2. IL-1 Family Cytokines, Receptors and Co-Receptors

The IL-1 family of cytokines is composed of 11 cytokine members, with seven agonists (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-18, IL-33, IL-36α, IL-36β, and IL-36γ) and four antagonists (IL-1 receptor antagonist (Ra), IL-36Ra, IL-37, and IL-38) [1]. According to their structural and functional characteristics, these cytokines are further classified into four subfamilies (IL-1, IL-18, IL-33, and IL-36), each one having a cognate receptor (IL-1R1, IL-18Rα, IL-33R (suppression of tumorigenicity 2 or ST2), and IL-36R, respectively). Furthermore, IL-1RAcP is an accessory protein shared by all these cytokines, with the exception of IL-18 (IL-18RAcP or IL-18Rβ chain) (Table 1) [2].

Table 1. IL-1 family cytokine members.

| Cytokines | Receptors (Other Names) | Co-Receptors (Other Names) | Function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1 | IL-1α | IL-1R1 | IL-1RAcP (IL1-R3) | Pro-inflammatory |

| IL-1β | IL-1R2 | |||

| IL-1Ra | IL-1R1 | N/A | Antagonist | |

| IL-18 | IL-18Rα (IL1-R5) | IL-18Rβ (IL-18RAcP or IL1R7) | Pro-inflammatory | |

| IL-33 | ST2 (IL-33R or IL1-R4) | IL-1RAcP | Pro-inflammatory Th2 responses | |

| IL-36 | IL-36α | IL-36R (IL-1Rrp2 or IL-R6) | IL-1RAcP (IL1-R3) | Pro-inflammatory |

| IL-36β | ||||

| IL-36γ | ||||

| IL-36Ra | IL-36R (IL-1Rrp2 or IL-R6) | N/A | Antagonist | |

| IL-37 | IL-18Rα (IL1-R5) | IL-1R8 (SIGIRR or TIR8) | Antagonist | |

| IL-38 | IL-36R (IL-1Rrp2 or IL1-R6) IL-R9 | IL1RAPL1 (TIGIRR-2) IL1RAPL2 (TIGIRR-1) | Antagonist/anti-inflammatory | |

SIGIRR: single immunoglobulin IL-1R-related molecule; TIR: toll-IL1R; IL1RAPL1 and IL1RAPL2: IL-1 receptor accessory protein like 1 and 2; TIGIRR 1 and 2: three immunoglobulin domain-containing IL-1 receptor-related 1 and 2.

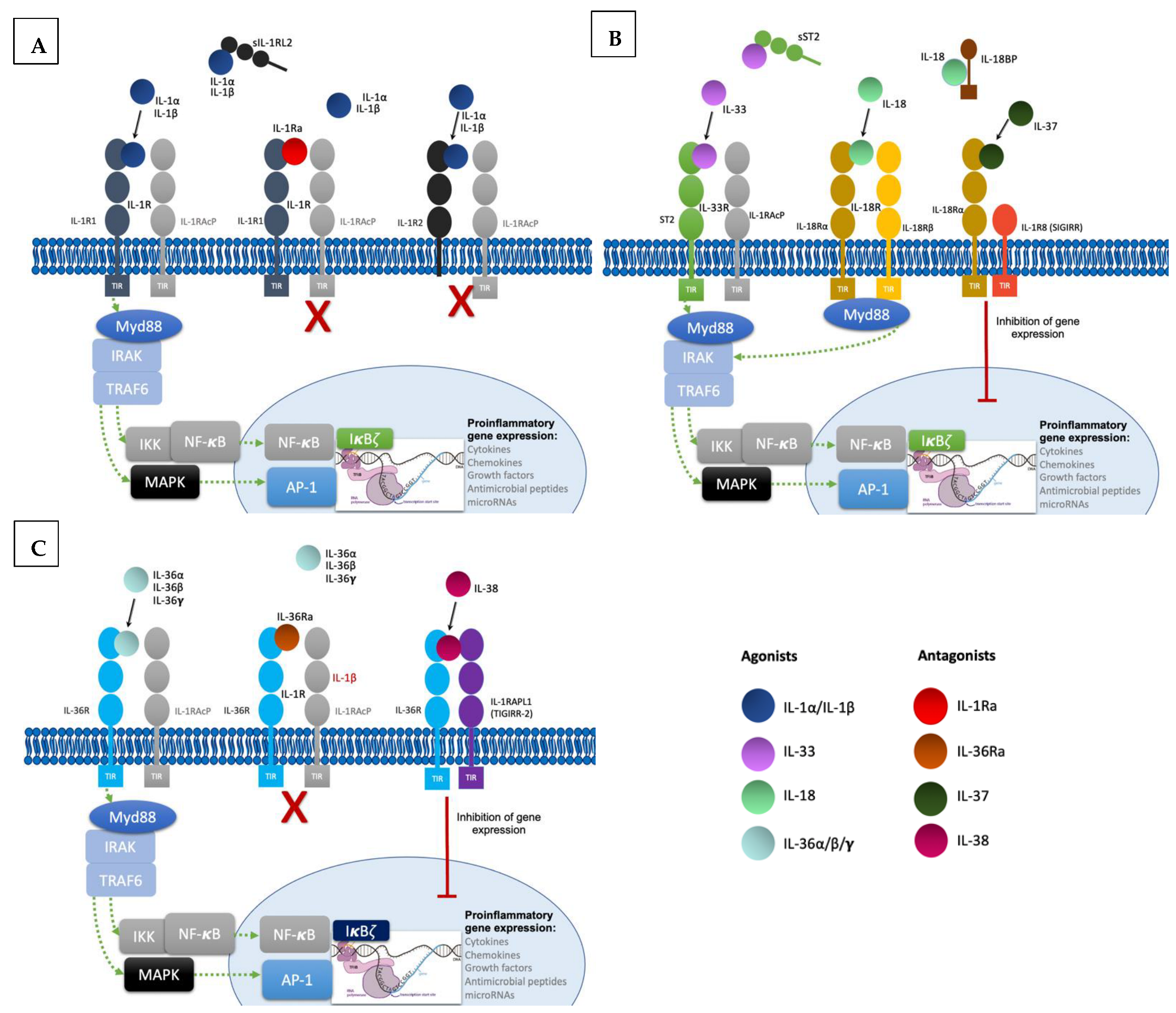

To produce their pro-inflammatory functions, IL-1 cytokines form complexes with their respective receptor and a co-receptor (Figure 1). All of them except IL-1Ra are synthesized as precursors and require N-terminal processing in order to acquire their full function [3][4]. They can be activated both extracellularly by proteolytic cleavage and intracellularly via inflammasome-mediated cleavage [5]. Binding of cleaved IL-1α/β to the extracellular domain of IL-1R1 leads to recruitment of IL-1RAcP, resulting in the initiation of a signaling cascade with the recruitment of the myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) accessory protein and Interleukin 1 receptor-associated kinases (IRAKs). This in turn results in activation of the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), ultimately resulting in pro-inflammatory gene expression [6]. Furthermore, IL-1 signaling also induces activation of defense mechanisms (antigen recognition, phagocytosis, degranulation, and nitric oxide production) and activates lymphocyte functions implicated in adaptive immunity, thus acting as a link between innate and adaptive immune responses [7]. The other IL-1 family cytokines IL-33, IL-18, and IL-36α/β/γ form similar ternary complexes with their respective receptors and co-receptors and also act through Myd88 to induce pro-inflammatory gene expression.

Figure 1. Signaling pathways and regulatory mechanisms involved in the IL-1 family. (A). Upon binding of IL-1α and IL-β to their receptor IL-1R1 altogether with co-receptor IL-1RAcP, induction of signal transduction with recruitment of myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) accessory protein and IL-1R associated kinase (IRAK) proteins, ultimately ending in the activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NF- κB) and the transcription of proinflammatory genes. Regulatory mechanisms include IL-1R2 and IL-1Ra: IL-1R2 can exist as a soluble receptor or membrane bound, acting as a decoy receptor as it is unable to recruit the co-receptor to induce signal transduction. Finally, IL-1Ra acts as a competitive inhibitor by binding to IL-1R1. (B). Likewise, IL-33 binds to the receptor ST2, inducing the recruitment of co-receptor IL-1RAcP and resulting in signal transduction into the nucleus with transcription of proinflammatory genes. In this family, the soluble form of ST2 also acts as a decoy receptor. IL-18 binds to IL-18Rα and recruits the co-receptor IL-18Rβ resulting in pro-inflammatory signaling. IL-18 binds to the soluble protein IL-18BP preventing binding to the receptor. IL-37 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine and upon binding to IL-18Rα induces recruitment of the Single Ig and TIR Domain Containing (SIGIRR or IL-1R8), ultimately producing inhibitory signaling. (C). IL-36 cytokines also induce pro-inflammatory gene transcription by binding to the receptor IL-36R and recruiting co-receptor IL-1RAcP. IL-36Ra is the competitive antagonist of IL-36 cytokines. The anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-38 forms a complex with IL-36R and three immunoglobulin domain-containing IL-1 receptor-related 2 (TIGIRR-2 or IL1RAPL1), also inducing inhibitory signaling to regulate the pro-inflammatory gene activation.

Regulatory mechanisms are necessary to maintain homeostasis; they include decoy receptors, receptor antagonists, and anti-inflammatory cytokines (Figure 1). IL-1R2 is a cytoplasmic soluble receptor without a functional TIR domain that binds to IL-1α/β precursors, preventing their processing and secretion. Under proinflammatory conditions, IL-1R2 is cleaved by an inflammasome-dependent mechanism [8][9]. Likewise, the soluble ST2 receptor (sST2) and the soluble protein IL-18 binding protein (IL-18BP) bind to IL-33 and IL-18, respectively, neutralizing their activities [10][11]. Furthermore, receptor antagonists IL-1Ra, IL-36Ra, and IL-38 compete with IL-1α/β and IL-36α/β/γ [4]. Lastly, IL-37 binding to IL-18Rα leads to recruitment of the IL-1R8 co-receptor (also called single immunoglobulin IL-1R-related molecule (SIGIRR), with activation of the inhibitory STAT3 signaling pathway [12].

2.1. IL-1 Subfamily

IL-1α and IL-β are both pro-inflammatory cytokines with some distinctive characteristics. IL-1α is constitutively expressed in hematopoietic immune cells and other cell types such as intestinal epithelial cells and cutaneous keratinocytes (KCs) [13]. Although non-processed full-length IL-1α has some functional activity, cleavage by calpain and extracellular proteases such as neutrophil elastase, granzyme B, and mast cell chymase enhances its pro-inflammatory activity [14][15]. Its major role is played locally, since IL-1α is mostly found bound to membranes. It is also expressed intracellularly in the cytosol—acting as an alarmin upon release from necrotic cell death—and in the nucleus—activating transcription of pro-inflammatory genes or tissue homeostasis and repair genes [16]. In addition, IL-1α expression can be induced by proinflammatory stimuli, leading to IL-1R1 binding and pro-inflammatory gene expression targeting type 1 or type 17 immune responses. In turn, this produces recruitment and activation of T cells, dendritic cells (DCs), neutrophils, and monocytes/macrophages that will release further pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, leading to an autoinflammatory amplification loop [17]. On the contrary, IL-1β is the primary circulating form, and its expression is inducible only in monocytes, macrophages, and DCs [17]. Full-length IL-1β precursor protein (pro-IL-1β) is stored in the cytoplasm and is cleaved by caspase-1 to its active form in response to activation of pattern recognition receptors (PPR) by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) in an inflammasome-dependent process [18]. In addition, pro-IL-1β can also be activated in the extracellular space by neutrophils and mast cells-derived proteases or by microbial proteases [19]. The antagonist IL-1Ra exerts its anti-inflammatory properties by binding to the IL-1R1 receptor and competing with IL-1α and IL-β [20].

2.2. IL-18 Subfamily

IL-18 is also a pro-inflammatory cytokine and is constitutively expressed in its inactive form in several cell types, mainly KCs, epithelial, and endothelial cells [21]. Its activation can be produced intracellularly by caspase-1-mediated cleavage or extracellularly by neutrophil or cytotoxic cell-derived proteases [21][22]. IL-18 pro-inflammatory activity is mainly mediated through IFNγ, but it can induce both Th1 and Th2 cellular responses [23]. In combination with IL-12 and IL-15, IL-18 stimulates Th1 cells and induces NK cell effector function and IFNγ expression [24][25]; in the absence of these cytokines, IL-18 induces a Th2 response with mast cell and basophil activation, ultimately ending in IL-4 and IL-13 production [26]. Moreover, when combined with IL-23, IL-18 activates Th17 cells and induces IL-17 production [27]. IL-18-BP regulates IL-18 pro-inflammatory activity by binding and sequestering the cytokine. IL-18-BP expression is induced by IFNγ, thus creating a negative feedback mechanism and decreasing inflammation [11].

2.3. IL-33 Subfamily

IL-33 is also constitutively expressed in many organs, mainly by fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells; its expression can also be induced in mast cells and DCs in the context of inflammation. Similar to IL-1α, IL-33 requires cleavage to increase its activity and has a dual role: intracellular gene expression regulating homeostasis and extracellular recruitment and activation of immune cells upon cell necrosis and inflammation (alarmin function) [28][29]. Th2 cells, mast cells, and eosinophils express the IL-33 receptor, ST2, or IL1-1RL1 [28]. IL-33 is a promoter of Th2 immunity and allergic responses, inducing production of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, polarization of macrophages and degranulation of mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils with cytokine and chemokine release [30]. Finally, IL-33 also acts on T-reg cells, DCs, and NK cells [31].

2.4. IL-36 Subfamily

The IL-36 subfamily is a key regulator of the innate immune system and includes three agonists with pro-inflammatory activity (IL-36α, IL-36β, and IL-36γ) and two antagonists (IL-36RN or IL-36Ra and IL-38) [32]. They are normally expressed in epithelial and immune cells; after binding to receptor complex IL-36R, agonists induce activation of nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) and mitogen-activated protein kinases, leading to T-cell proliferation, expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and co-stimulatory molecules by DCs and Th1 lymphocytes, as well as autocrine KCs signaling. The resulting pro-inflammatory milieu is composed of IL-1β, IL-12, IL-23, IL-6, TNF-α, CCL1, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL8, and GM-CSF, among others [32]. IL-36α and IL-36γ are mainly produced by KCs but also by dermal fibroblasts, endothelial cells, macrophages, LCs, and DCs. As opposed to other IL-1 family cytokines, IL-36 cytokines are also produced as precursors but do not contain a caspase cleavage site. Following secretion, they are activated by neutrophil-derived proteases present at neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs)—such as elastase, cathepsin G, and proteinase 3—and by cathepsin S, produced by KCs and fibroblasts [33][34][35]. In addition, KCs secrete the protease inhibitors alpha-1-antitrypsin and alpha-1-antichymotrypsin (encoded by SERPINA1 and SERPINA3 genes), which inhibit processing of IL-36 cytokines by neutrophil proteases and thus regulate the inflammatory loop [36].

2.5. IL-37 and IL-38: Antagonist Cytokines

IL-37 acts as an anti-inflammatory cytokine and is constitutively expressed mainly in KCs, but can be induced in monocytes/macrophages, T cells, and B cells. It has a dual action, depending on extracellular or intracellular signaling. Extracellularly, IL-37 binds IL-18Rα and recruits IL-1R8 to form the IL-37/IL-1R8/IL-18Rα complex, restricting IL-18R-dependent inflammation and inhibiting innate immunity [12]. In the cytosol, IL-37 cleaved by caspase-1 translocates to the nucleus to bind Smad transcription factors, ultimately decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokine production. The precursor exhibits activity, but cleaved IL-37 binds more effectively to its receptor [37].

IL-38 also acts as an anti-inflammatory cytokine and is expressed in skin and various immune cells, such as B cells. It specifically binds to IL-36R and inhibits human mononuclear cells stimulated with IL-36 in vitro [38]. IL-38 expression is inhibited by IL-17, IL-22, and IL-36γ [4]. Furthermore, IL-38 is able to suppress the production of IL-17A by γδ T-cells through IL-1RAcP antagonism [39].

References

- Boutet, M.-A.; Nerviani, A.; Pitzalis, C. IL-36, IL-37, and IL-38 Cytokines in Skin and Joint Inflammation: A Comprehensive Review of Their Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1257.

- Hernandez-Santana, Y.E.; Giannoudaki, E.; Leon, G.; Lucitt, M.B.; Walsh, P.T. Current Perspectives on the Interleukin-1 Family as Targets for Inflammatory Disease. Eur. J. Immunol. 2019, 49, 1306–1320.

- Towne, J.E.; Renshaw, B.R.; Douangpanya, J.; Lipsky, B.P.; Shen, M.; Gabel, C.A.; Sims, J.E. Interleukin-36 (IL-36) Ligands Require Processing for Full Agonist (IL-36α, IL-36β, and IL-36γ) or Antagonist (IL-36Ra) Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 42594–42602.

- Mora, J.; Weigert, A. IL-1 Family Cytokines in Cancer Immunity—A Matter of Life and Death. Biol. Chem. 2016, 397, 1125–1134.

- Uppala, R.; Tsoi, L.C.; Harms, P.W.; Wang, B.; Billi, A.C.; Maverakis, E.; Michelle Kahlenberg, J.; Ward, N.L.; Gudjonsson, J.E. “Autoinflammatory Psoriasis”-Genetics and Biology of Pustular Psoriasis. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2020, 18, 307–317.

- Matarazzo, L.; Hernandez Santana, Y.E.; Walsh, P.T.; Fallon, P.G. The IL-1 Cytokine Family as Custodians of Barrier Immunity. Cytokine 2022, 154, 155890.

- Dinarello, C.A. Overview of the IL-1 Family in Innate Inflammation and Acquired Immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 281, 8–27.

- Shimizu, K.; Nakajima, A.; Sudo, K.; Liu, Y.; Mizoroki, A.; Ikarashi, T.; Horai, R.; Kakuta, S.; Watanabe, T.; Iwakura, Y. IL-1 Receptor Type 2 Suppresses Collagen-Induced Arthritis by Inhibiting IL-1 Signal on Macrophages. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 3156–3168.

- Zheng, Y.; Humphry, M.; Maguire, J.J.; Bennett, M.R.; Clarke, M.C.H. Intracellular Interleukin-1 Receptor 2 Binding Prevents Cleavage and Activity of Interleukin-1α, Controlling Necrosis-Induced Sterile Inflammation. Immunity 2013, 38, 285–295.

- Fields, J.K.; Günther, S.; Sundberg, E.J. Structural Basis of IL-1 Family Cytokine Signaling. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1412.

- Dinarello, C.; Novick, D.; Kim, S.; Kaplanski, G. Interleukin-18 and IL-18 Binding Protein. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 289.

- Nold-Petry, C.A.; Lo, C.Y.; Rudloff, I.; Elgass, K.D.; Li, S.; Gantier, M.P.; Lotz-Havla, A.S.; Gersting, S.W.; Cho, S.X.; Lao, J.C.; et al. IL-37 Requires the Receptors IL-18Rα and IL-1R8 (SIGIRR) to Carry out Its Multifaceted Anti-Inflammatory Program upon Innate Signal Transduction. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 354–365.

- Di Paolo, N.C.; Shayakhmetov, D.M. Interleukin 1α and the Inflammatory Process. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 906–913.

- Afonina, I.S.; Tynan, G.A.; Logue, S.E.; Cullen, S.P.; Bots, M.; Lüthi, A.U.; Reeves, E.P.; McElvaney, N.G.; Medema, J.P.; Lavelle, E.C.; et al. Granzyme B-Dependent Proteolysis Acts as a Switch to Enhance the Proinflammatory Activity of IL-1α. Mol. Cell 2011, 44, 265–278.

- Kavita, U.; Mizel, S.B. Differential Sensitivity of Interleukin-1 Alpha and -Beta Precursor Proteins to Cleavage by Calpain, a Calcium-Dependent Protease. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 27758–27765.

- Bertheloot, D.; Latz, E. HMGB1, IL-1α, IL-33 and S100 Proteins: Dual-Function Alarmins. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2017, 14, 43–64.

- Mantovani, A.; Dinarello, C.A.; Molgora, M.; Garlanda, C. Interleukin-1 and Related Cytokines in the Regulation of Inflammation and Immunity. Immunity 2019, 50, 778–795.

- Zhou, L.; Todorovic, V. Interleukin-36: Structure, Signaling and Function. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 2020, 191–210.

- Guma, M.; Ronacher, L.; Liu-Bryan, R.; Takai, S.; Karin, M.; Corr, M. Caspase 1-Independent Activation of Interleukin-1beta in Neutrophil-Predominant Inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60, 3642–3650.

- Højen, J.F.; Kristensen, M.L.V.; McKee, A.S.; Wade, M.T.; Azam, T.; Lunding, L.P.; de Graaf, D.M.; Swartzwelter, B.J.; Wegmann, M.; Tolstrup, M.; et al. IL-1R3 Blockade Broadly Attenuates the Functions of Six Members of the IL-1 Family, Revealing Their Contribution to Models of Disease. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 1138–1149.

- Kaplanski, G. Interleukin-18: Biological Properties and Role in Disease Pathogenesis. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 281, 138–153.

- Yasuda, K.; Nakanishi, K.; Tsutsui, H. Interleukin-18 in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 649.

- Xu, D.; Trajkovic, V.; Hunter, D.; Leung, B.P.; Schulz, K.; Gracie, J.A.; McInnes, I.B.; Liew, F.Y. IL-18 Induces the Differentiation of Th1 or Th2 Cells Depending upon Cytokine Milieu and Genetic Background. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000, 30, 3147–3156.

- Oka, N.; Markova, T.; Tsuzuki, K.; Li, W.; El-Darawish, Y.; Pencheva-Demireva, M.; Yamanishi, K.; Yamanishi, H.; Sakagami, M.; Tanaka, Y.; et al. IL-12 Regulates the Expansion, Phenotype, and Function of Murine NK Cells Activated by IL-15 and IL-18. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020, 69, 1699–1712.

- Quatrini, L.; Vacca, P.; Tumino, N.; Besi, F.; Pace, A.L.D.; Scordamaglia, F.; Martini, S.; Munari, E.; Mingari, M.C.; Ugolini, S.; et al. Glucocorticoids and the Cytokines IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 Present in the Tumor Microenvironment Induce PD-1 Expression on Human Natural Killer Cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 349–360.

- Yoshimoto, T.; Tsutsui, H.; Tominaga, K.; Hoshino, K.; Okamura, H.; Akira, S.; Paul, W.E.; Nakanishi, K. IL-18, Although Antiallergic When Administered with IL-12, Stimulates IL-4 and Histamine Release by Basophils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 13962–13966.

- Niu, X.-L.; Huang, Y.; Gao, Y.-L.; Sun, Y.-Z.; Han, Y.; Chen, H.-D.; Gao, X.-H.; Qi, R.-Q. Interleukin-18 Exacerbates Skin Inflammation and Affects Microabscesses and Scale Formation in a Mouse Model of Imiquimod-Induced Psoriasis. Chin. Med. J. 2019, 132, 690–698.

- Cayrol, C.; Girard, J.-P. Interleukin-33 (IL-33): A Nuclear Cytokine from the IL-1 Family. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 281, 154–168.

- Hung, L.-Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Herbine, K.; Pastore, C.; Singh, B.; Ferguson, A.; Vora, N.; Douglas, B.; Zullo, K.; Behrens, E.M.; et al. Cellular Context of IL-33 Expression Dictates Impact on Anti-Helminth Immunity. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5, eabc6259.

- Cannavò, S.P.; Bertino, L.; Di Salvo, E.; Papaianni, V.; Ventura-Spagnolo, E.; Gangemi, S. Possible Roles of IL-33 in the Innate-Adaptive Immune Crosstalk of Psoriasis Pathogenesis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2019, 2019, 7158014.

- Smithgall, M.D.; Comeau, M.R.; Yoon, B.-R.P.; Kaufman, D.; Armitage, R.; Smith, D.E. IL-33 Amplifies Both Th1- and Th2-Type Responses through Its Activity on Human Basophils, Allergen-Reactive Th2 Cells, INKT and NK Cells. Int. Immunol. 2008, 20, 1019–1030.

- Han, Y.; Huard, A.; Mora, J.; da Silva, P.; Brüne, B.; Weigert, A. IL-36 Family Cytokines in Protective versus Destructive Inflammation. Cell. Signal. 2020, 75, 109773.

- Clancy, D.M.; Henry, C.M.; Sullivan, G.P.; Martin, S.J. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Can Serve as Platforms for Processing and Activation of IL-1 Family Cytokines. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 1712–1725.

- Clancy, D.M.; Sullivan, G.P.; Moran, H.B.T.; Henry, C.M.; Reeves, E.P.; McElvaney, N.G.; Lavelle, E.C.; Martin, S.J. Extracellular Neutrophil Proteases Are Efficient Regulators of IL-1, IL-33, and IL-36 Cytokine Activity but Poor Effectors of Microbial Killing. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 2937–2950.

- Henry, C.M.; Sullivan, G.P.; Clancy, D.M.; Afonina, I.S.; Kulms, D.; Martin, S.J. Neutrophil-Derived Proteases Escalate Inflammation through Activation of IL-36 Family Cytokines. Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 708–722.

- Johnston, A.; Xing, X.; Wolterink, L.; Barnes, D.H.; Yin, Z.; Reingold, L.; Kahlenberg, J.M.; Harms, P.W.; Gudjonsson, J.E. IL-1 and IL-36 Are Dominant Cytokines in Generalized Pustular Psoriasis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 109–120.

- Pan, Y.; Wen, X.; Hao, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; He, G.; Jiang, X. The Role of IL-37 in Skin and Connective Tissue Diseases. Biomed. Pharm. 2020, 122, 109705.

- Conti, P.; Pregliasco, F.E.; Bellomo, R.G.; Gallenga, C.E.; Caraffa, A.; Kritas, S.K.; Lauritano, D.; Ronconi, G. Mast Cell Cytokines IL-1, IL-33, and IL-36 Mediate Skin Inflammation in Psoriasis: A Novel Therapeutic Approach with the Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines IL-37, IL-38, and IL-1Ra. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8076.

- Han, Y.; Mora, J.; Huard, A.; da Silva, P.; Wiechmann, S.; Putyrski, M.; Schuster, C.; Elwakeel, E.; Lang, G.; Scholz, A.; et al. IL-38 Ameliorates Skin Inflammation and Limits IL-17 Production from Γδ T Cells. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 835–846.e5.

More

Information

Subjects:

Dermatology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

06 Sep 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No