| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Luigi Mandrich | -- | 4564 | 2022-08-30 12:44:56 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | -1122 word(s) | 3442 | 2022-09-05 03:13:46 | | | | |

| 3 | Beatrix Zheng | Meta information modification | 3442 | 2022-09-05 03:31:04 | | | | |

| 4 | Beatrix Zheng | Meta information modification | 3442 | 2022-09-05 03:55:32 | | | | |

| 5 | Beatrix Zheng | -13 word(s) | 3429 | 2022-09-05 09:37:00 | | |

Video Upload Options

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, reported for the first time at the end of 2019 in the city of Wuhan (China), has spread worldwide in three years; it lead to the infection of more than 500 million people and about six million dead. SARS-CoV-2 has proved to be very dangerous for human health. Therefore, several efforts have been made in studying this virus. In a short time, about one year, the mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 infection and duplication and its physiological effect on human have been pointed out. Moreover, different vaccines against it have been developed and commercialized. Since the beginning of the pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 has evolved; it has done so by accumulating mutations in the genome, generating new virus versions showing different characteristics, and which have replaced the pre-existing variants. In general, it has been observed that the new variants show an increased infectivity and cause milder symptoms. The latest isolated Omicron variants contain more than 50 mutations in the whole genome and show an infectivity 10-folds higher compared to the wild-type strain.

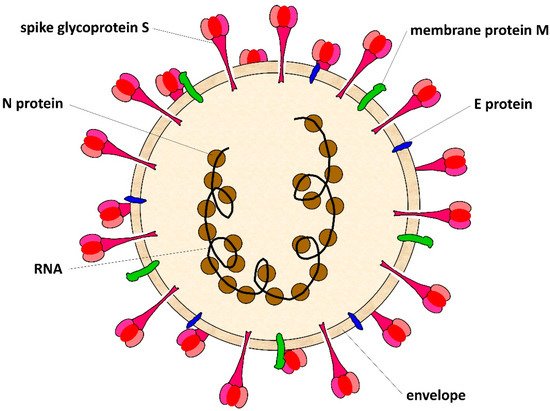

1. SARS-CoV-2 Virus

2. SARS-CoV-2 Mutation Rate

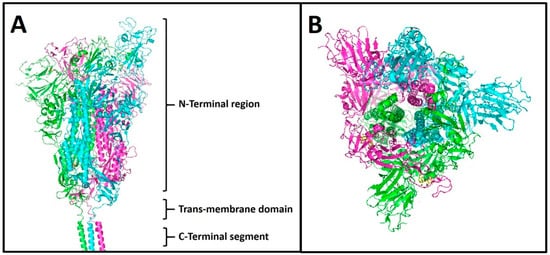

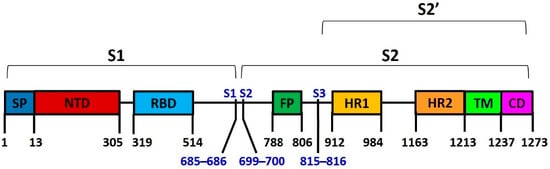

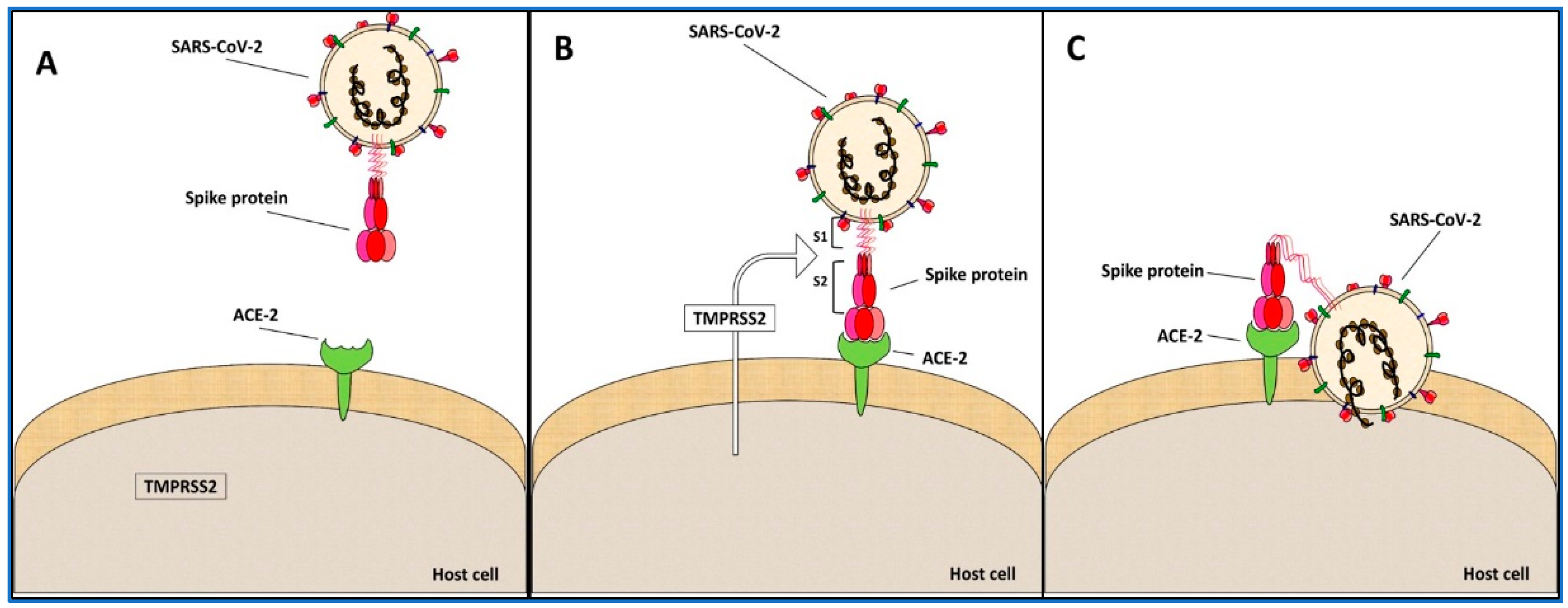

3. Spike Protein S

4. Spike Variants and Phylogenies

Casual mutations occur during the viral RNA replication, generating new SARS-CoV-2 variants. Only some of these mutations had an effect on the processes of viral infection and diffusion, as well as on the virus-induced symptoms; others are harmful for the survival of the virus and are eliminated, and some are neutral and are accumulated in the genome. In the three years of the pandemic, many SARS-CoV-2 variants have been observed and sequenced [27]. The spike protein has been used as the primary antigen for the vaccine production because it is crucial for the infection mechanism and it is a characterising SARS-CoV-2 protein. Further, the mutations observed in the gene coding this protein have been used for the classification of the viral variants [28]. The most diffused SARS-CoV-2 variants have mutations capable of changing the virus infection and diffusion processes; they have spread, replacing the wild-type or the previous virus variants [29][30].

The most recent SARS-CoV-2 variants have accumulated many mutations on the spike protein. Thus, since the vaccines have been developed on the wild-type version of spike, many cases of reinfection by COVID-19 and infections in vaccinated people have been observed[31].

Here, the researchers analysed the most diffused SARS-CoV-2 variants by sequence alignment, in relation to the timing of their spreading and the place where they were first isolated. The researchers did so in order to perform a phylogenetic analysis to understand the genetic evolution of the virus, and to define the characterizing mutations of SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1) during its evolution.

Table 1. SARS-CoV-2 variants. The most spread SARS-CoV-2 variants, the country where they were first isolated, and the isolation dates were reported.

|

Spike Variants |

Isolation Country |

Isolation Date |

|

wild type |

China |

December 2019 |

|

EPSILON |

USA |

March 2020 |

|

ZETA |

Brazil |

April 2020 |

|

BETA |

South Africa |

May 2020 |

|

20 A.EU2 |

Portugal |

June2020 |

|

20 A.EU1 |

Spain |

July 2020 |

|

ALPHA |

England |

September 2020 |

|

DELTA |

India |

October 2020 |

|

KAPPA |

India |

October 2020 |

|

A 23.1 |

Uganda |

October 2020 |

|

GAMMA |

Brazil |

November 2020 |

|

IOTA |

USA |

November 2020 |

|

ETA |

Multiple countries |

November 2020 |

|

LAMBDA |

Peru |

December 2020 |

|

THETA |

Philippines |

January 2021 |

|

B.1.1.318 |

Multiple countries |

January 2021 |

|

MU |

Columbia |

January 2021 |

|

OMICRON BA.1 |

South Africa |

November 2021 |

|

OMICRON BA.2 |

South Africa |

December 2021 |

|

OMICRON BA.2.12.1 |

North America |

December 2021 |

|

OMICRON BA.4 |

South Africa |

January 2022 |

|

OMICRON BA.5 |

South Africa |

January 2022 |

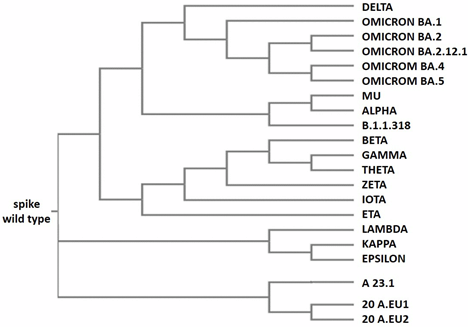

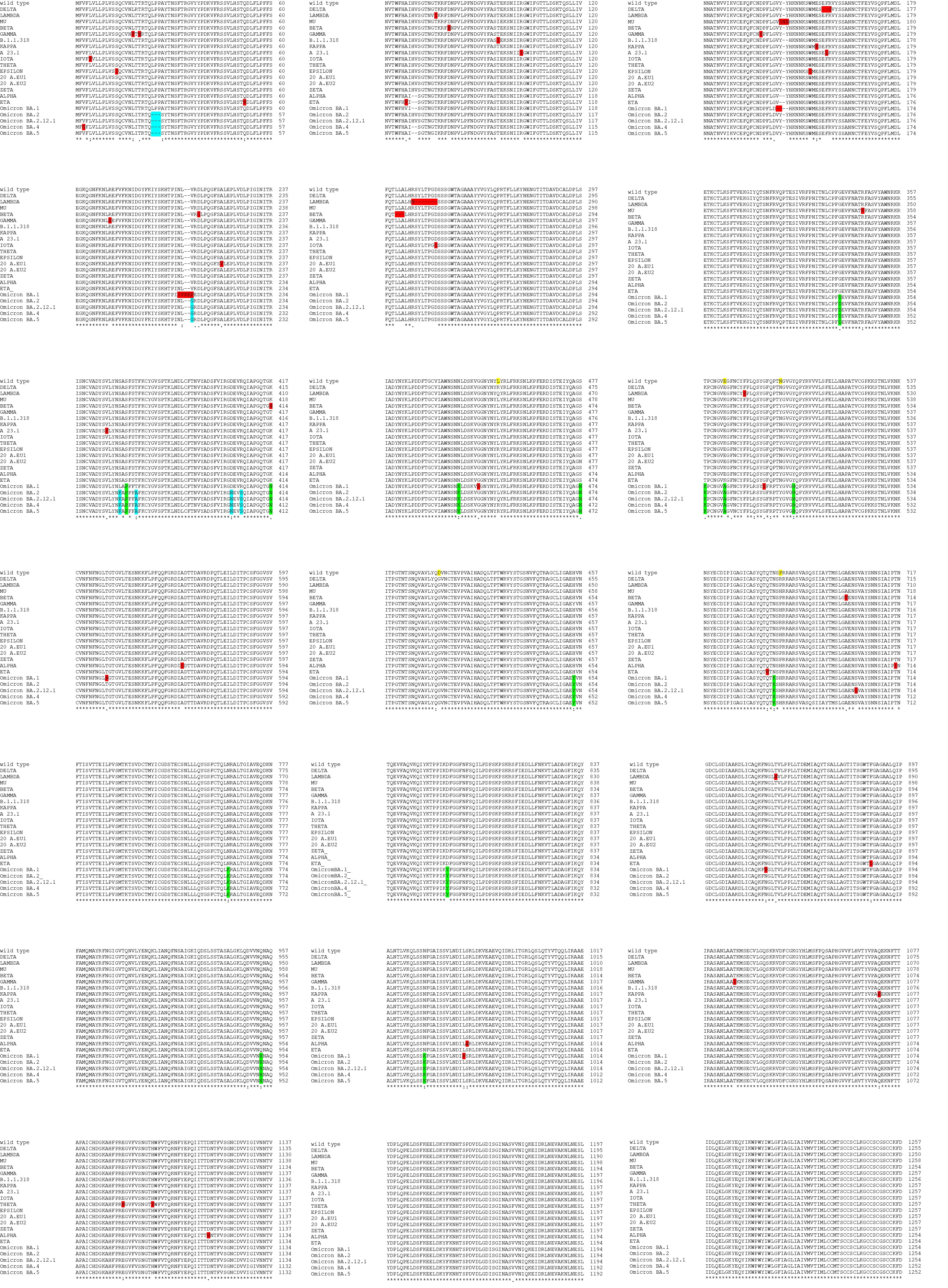

The twenty most diffused SARS-CoV-2 spike variants, identified from December 2019 to the beginning of 2022, indicated as wild type, delta, lambda, mu, beta, gamma, B.1.1.318, kappa, A 23.1, iota, theta, epsilon, 20 A.EU1, 20 A.EU2, zeta, alpha, eta, omicron BA.1, omicron BA.2, omicron BA.2.12.1, omicron BA.4, and omicron BA.5 (sequences were from proteins database at https://www.uniprot.org, accessed on December 2003) were selected for the analysis. The sequences of these variants were used to make the multiple sequence alignment reported in figure S1 (see supplemental data) (the multiple sequence alignment by the Clustal Omega program at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/, accessed on 01 October 2019). From the alignment is derived the phylogenetic tree of the variants that will be discussed below.

The researchers found 100 mutations in total, including residue substitutions, deletions, and insertions, which are about 8% of the total residues (1273 aa). Moreover, 49 of these mutations were included in NTD and 23 in the RBD domain; they were comprised in more than 70% of the S1 spike subunit mutations (Figure 3).

These data suggested that the greatest changes occur in the recognition region of the ACE-2 host cell receptor [32], while the spike protein domains involved in the conformational changes and in its activation did not vary. Further, these results supported that the virus infection rate variation observed in these variants was correlated to the change of the binding affinity of the spike protein to the ACE-2 protein [32].

Interestingly, only the residue D614 is mutated in all the examined variants, excluding the variant A 23.1, that maintain D614 (Figure S1, supplemental data); this observation indicates that one of the first mutations that occurred in the spike was at position 614, and it is known that the mutation of this residue impacts on the functionality of the protein [33].

Among the other mutations, the most diffused are at the following positions: 452 (in 7 variants); 484 (in 13 variants); 501 (in 10 variants); and 681 (in 12 variants). Further, 51 mutations are unique for the variants; among them, 20 have been identified only in the Omicron variants (Table 2).

Table 2. A list of single mutations in the spike variants. For each variant, only the exclusive and unique mutations sequenced were reported. “Del” is a deletion of residues; “Ins” is an insertion of residues.

|

Spike Variants |

Mutations |

|

ALPHA |

A570D T716I S982A D1118H |

|

BETA |

D80A D215G Del241-243 K417N A701V |

|

GAMMA |

L18F T20N D138Y R190S T1027I |

|

DELTA |

Del156-157 R158G |

|

EPSILON |

S13I W152C |

|

ETA |

Q52R A67V Q677H F888L |

|

THETA |

E1092K H1101Y |

|

IOTA |

L5F D253G |

|

KAPPA |

E154K Q1071H |

|

LAMBDA |

T76I R246N Del247-252 F490S T859N |

|

MU |

Ins147N Y147N R346K |

|

20 A.EU1 |

A222V |

|

A 23.1 |

R102I F157L V367F |

|

B.1.1.318 |

T95I |

|

OMICRON BA.1 |

Del143-144 N211I L212V Ins213-214 V215P G446S G449S T547K N856K L981F |

|

OMICRON BA.2.12.1 |

S704L |

|

OMICRON BA.4 |

V3G |

Furthermore, the researchers observed that the “unique” mutations listed in Table 2 cannot be considered variant-specific and all characterising the SARS-CoV-2 variants; this is because in most cases they are substitutions between amino acids with similar properties, not affecting the spike protein functionality. For instance, in the 20 A.EU 1 and 2 variants, the spike protein differs from the wild type by the same single residue (D614G) in both. In addition, another two mutations were found: the S477N in the variant 20 A.EU 2; and the A222V in the variant 20 A.EU 1. The mutation S477N was also identified in other spike variants, while A222V was observed only in 20 A.EU 1; this suggests that the functional difference between the two 20 A.EU variants is due to the S477N mutation and not due to the A222V, being a conservative substitution of a non-polar amino acid with a similar one [34]. Based on these observations, if the mutation S477N is characterising between these two variants and it is also present in other more recent variants, 20 A.EU 2 may be considered an old variant, where the mutation S477N appeared for the first time.

In the case of the variant named Iota, some mutations are common to other variants, such as S477N, E484K, and D614G; however, the two mutations found only in Iota, L5F, and D253G can be considered characterizing because they have an effect on the functionality of the spike. In fact, the L5F mutation is localized in the signal peptide (SP) of the spike; it has been observed that mutations of SP alter the spike functionality [35]. The second mutation D253G is the substitution of polar residues (aspartic, D) with non-polar ones (glycine, G), generating a consistent change.

Other characterising mutations observed in the spike variants affecting its functionality are: the deletion 156–158 in Delta; the deletion 241–243 in Beta; and the deletion 246–252 in Lambda (Table 2).

5. The Omicron Variants

At the end of 2021, a new SARS-CoV-2 variant named Omicron was isolated in South Africa and Botswana; it was, successively, sequenced (Organization WH. Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern. 2021. https://www.who.intnewsitem/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern, accessed on 26 November 2021).

Omicron, compared to the previously variants, is characterised by having many mutations; it has about 50 on the whole genome and 32 of them are only in the spike protein [36]. As regards its main features, Omicron shows an increased infectivity (10-folds higher with respect to the wild-type strain) and milder symptoms with respect to the original virus [36]. This variant is also able to escape the immune system of the host due to the high number of mutations on the spike protein. This led to an extremely fast spreading of the Omicron variant in South Africa, such that it completely replaced the Delta variant in only two weeks [36]. Due to its rapid spreading and high capability to mutate, from November 2021 to January 2022, four Omicron sub-variants were isolated (Table 1).

Among the mutations identified in the Omicron variants, 14 are exclusive and found in all the Omicron variants. They are: G339D, S373P, K417N, N440K, S477N, T478K, E484A, Y505H, H655Y, N679K, N764K, D796Y, Q954H, and N969K (Figure S1, supplemental data). However, six other mutations have been observed in all the Omicron variants, excluding Omicron BA.1; they are: Del24-26, V213G, T376A, S371F, D405N, and R408S (Figure S1, supplemental data).

From an evolutionary point of view, the Omicron variants are derived from a common “ancestral” version of the SARS-CoV-2 Alpha variant (Figure 5). In fact, they have some critical mutations in common; these are Del69-70, N501Y, D614G, and P681H, all of which are involved in the spike protein functionality [37][38][39]. Omicron BA.1 is quite different from the other omicron variants because it has 11 unique mutations with respect to the others (Table 2). For this reason, it is possible that it evolved separately from the other Omicron variants and was present at least 3–4 months before its isolation; otherwise, it could not have been so different from the other Omicron variants. These findings are evident in Figure 5, which represents the phylogenetic tree generated by the alignment reported in Figure S1 (supplemental data). In the upper part of Figure 5 are located the Omicron variants; together with Delta, they evolved from a common ancestor of the Alpha variant; and Omicron BA.1 appears in an evolutionary branch that separated early from the other Omicrons.

Figure 5. Phylogenetic tree of SARS-CoV-2 variants. The tree was generated by the alignment obtained using the Clustal Omega program (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/, accessed on 01 October 2019). For the alignment, the default parameters were used (dealign input sequences: no (false); number of combined iterations: 0; max guide tree iterations: −1 (off); max HMM iterations: −1 (off); use mBed-like clustering during subsequent iterations: yes (true); mBed-like clustering guide-tree: yes (true)).

In the lower part of Figure 5, the SAR-CoV-2 variants grouped as A 23.1, A 20.EU 1, A 20.EU 2, and Lambda, Kappa, and Epsilon appear in others’ early evolutionary branches evolved from the initial virus. It is important to note that the variant Epsilon was isolated and sequenced in the USA in March 2020. However, the variants A 23.1 and Lambda were isolated only in October 2020 and December 2020, respectively, in Uganda and Peru; in these two countries, for technical and economic reasons, not many samples were sequenced compared to the USA. It is interesting that the two variants Delta and Kappa were isolated in India, both in December 2020 (Table 1). It is evident that their evolution is divergent, by looking at the phylogenetic tree (Figure 5). In fact, both variants carry seven mutations with respect to the wild-type protein; however, only three of them are common, specifically: L452R, D614G, and P681R. This may suggest the presence of an unknown variant intermediate carrying these three mutations, which then diverged into the two variants Kappa and Delta.

The phylogenetic tree gives a clear idea of the variants’ evolution, even if it lacks an indication of some variants being less widespread and no detected intermediate variants; this is mainly regarding the Omicron variants that have many more mutations with respect to the others. Their evolution originated through a series of intermediate variants that are currently unknown.

SUPPLEMENTAL

Figure S1. Sequences alignment. SARS-CoV-2 wild type spike protein and its most diffused variants were aligned by using the Clustal Omega program (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). The parameters used were used by default of the program. In yellow are underlined wild type residues with high rate of mutation. In red are underlined mutations present only in a single variant. In green are underlined mutations present only in all the Omicron variants. In cyan are underlined mutations present in all the Omicron variants excluding Omicron BA.1.

References

- Krammer, F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature 2020, 586, 516–527.

- Castells, M.C.; Phillips, E.J. Maintaining Safety with SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 384, 643–649.

- Fiolet, T.; Kherabi, Y.; MacDonald, C.-J.; Ghosn, J.; Peiffer-Smadja, N. Comparing COVID-19 vaccines for their characteristics, efficacy and effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern: A narrative review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 202–221.

- Caputo, E.; Mandrich, L. SARS-coV-2 infection: A case family report. Glob. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 8, 83–88.

- Harrison, A.G.; Lin, T.; Wang, P. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 transmission and pathogenesis. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 1100–1115.

- Sternberg, A.; Naujokat, C. Structural features of coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Targets for vaccination. Life Sci. 2020, 257, 118056.

- Akram, F.; Haq, I.U.; Aqeel, A.; Ahmed, Z.; Shah, F.I.; Nawaz, A.; Zafar, J.; Sattar, R. Insights into the evolutionary and prophylactic analysis of SARS-CoV-2: A review. J. Virol. Methods 2022, 300, 114375.

- Focosi, D.; Maggi, F. Neutralising antibody escape of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Risk assessment for antibody-based Covid-19 therapeutics and vaccines. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021, 31, e2231.

- Chan, J.F.W.; Kok, K.H.; Zhu, Z.; Chu, H.; Wang-TO, K.K.; Yuan, S.; Yuen, K.-Y. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 221–236.

- Rohaim, M.A.; El Naggar, R.F.; Clayton, E.; Munir, M. Structural and functional insights into non-structural proteins of coronaviruses. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 150, 104641.

- Michel, C.J.; Mayer, C.; Poch, O.; Thompson, J.D. Characterization of accessory genes in coronavirus genomes. Virol. J. 2020, 17, 131.

- Mousavizadeh, L.; Ghasemi, S. Genotype and phenotype of COVID-19: Their roles in pathogenesis. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2021, 54, 159–163.

- Atzrodt, C.L.; Maknojia, I.; McCarthy, R.D.P.; Oldfield, T.M.; Po, J.; Ta, K.T.L.; Stepp, H.E.; Clements, T.P. A Guide to COVID-19: A global pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 3633–3650.

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Pöhlmann, S. A Multibasic Cleavage Site in the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Is Essential for Infection of Human Lung Cells. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 779–784.e775.

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE-2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8.

- Ou, X.; Liu, Y.; Lei, X.; Li, P.; Mi, D.; Ren, L.; Guo, L.; Guo, R.; Chen, T.; Hu, J.; et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1620.

- Drake, J.W. Rates of spontaneous mutation among RNA viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 4171–4175.

- Sanjuán, R.; Nebot, M.R.; Chirico, N.; Mansky, L.M.; Belshaw, R. Viral mutation rates. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 9733–9748.

- Koyama, T.; Platt, D.; Parida, L. Variant analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 495–504.

- Amicone, M.; Borges, V.; Alves, M.J.; Isidro, J.; Zè-Zè, L.; Duarte, S.; Vieira, L.; Guiomar, R.; Gomes, J.P.; Gordo, I. Mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2 and emergence of mutators during experimental evolution. Evol. Med. Public Health 2022, 10, 142–155.

- Callaway, E. The coronavirus is mutating—Does it matter? Nature 2020, 585, 174–177.

- Wang, Y.; Xu, G.; Huang, Y.-W. Modelling the load of SARS-CoV-2 virus in human expelled particles during coughing and speaking. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241539.

- Mistry, P.; Barmania, F.; Mellet, J.; Peta, K.; Strydom, A.; Viljoen, I.M.; James, W.; Gordon, S.; Pepper, M.S. SARS-CoV-2 Variants, Vaccines, and Host Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 809244.

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.S.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Abiona, O.; Graham, B.S.; McLellan, J.S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–1263.

- Huang, Y.; Yang, C.; Xu, X.-F.; Xu, W.; Liu, S.-W. Structural and functional properties of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Potential antivirus drug development for COVID-19. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 1141–1149.

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Niu, S.; Song, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, G.; Qiao, C.; Hu, Y.; Yuen, K.-Y.; et al. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell 2020, 181, 894–904.e9.

- William T. Harvey; Alessandro M. Carabelli; Ben Jackson; Ravindra K. Gupta; Emma C. Thomson; Ewan M. Harrison; Catherine Ludden; Richard Reeve; Andrew Rambaut; Sharon J. Peacock; et al.David L. Robertson SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2021, 19, 409-424, 10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0.

- Toon Braeye; Lucy Catteau; Ruben Brondeel; Joris A.F. van Loenhout; Kristiaan Proesmans; Laura Cornelissen; Herman Van Oyen; Veerle Stouten; Pierre Hubin; Matthieu Billuart; et al.Achille DjienaRomain MahieuNaima HammamiDieter Van CauterenChloé Wyndham-Thomas Vaccine effectiveness against onward transmission of SARS-CoV2-infection by variant of concern and time since vaccination, Belgian contact tracing, 2021. Vaccine 2022, 40, 3027-3037, 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.04.025.

- Bette Korber; Will M. Fischer; Sandrasegaram Gnanakaran; Hyejin Yoon; James Theiler; Werner Abfalterer; Nick Hengartner; Elena E. Giorgi; Tanmoy Bhattacharya; Brian Foley; et al.Kathryn M. HastieMatthew D. ParkerDavid G. PartridgeCariad M. EvansTimothy M. FreemanThushan I. de SilvaCharlene McDanalLautaro G. PerezHaili TangAlex Moon-WalkerSean P. WhelanCelia C. LaBrancheErica O. SaphireDavid C. MontefioriAdrienne AngyalRebecca L. BrownLaura CarrileroLuke R. GreenDanielle C. GrovesKatie J. JohnsonAlexander J. KeeleyBenjamin LindseyPaul ParsonsMohammad RazaSarah Rowland-JonesNikki SmithRachel M. TuckerDennis WangMatthew D. Wyles Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus. Cell 2020, 182, 812-827.e19, 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043.

- Nash D. Rochman; Yuri I. Wolf; Guilhem Faure; Pascal Mutz; Feng Zhang; Eugene V. Koonin; Ongoing global and regional adaptive evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2104241118, 10.1073/pnas.2104241118.

- Anirban Goutam Mukherjee; Uddesh Ramesh Wanjari; Reshma Murali; Uma Chaudhary; Kaviyarasi Renu; HarishKumar Madhyastha; Mahalaxmi Iyer; Balachandar Vellingiri; Abilash Valsala Gopalakrishnan; Omicron variant infection and the associated immunological scenario. Immunobiology 2022, 227, 152222, 10.1016/j.imbio.2022.152222.

- Carmen Gómez; Beatriz Perdiguero; Mariano Esteban; Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants and Impact in Global Vaccination Programs against SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19. Vaccines 2021, 9, 243, 10.3390/vaccines9030243.

- Manojit Bhattacharya; Srijan Chatterjee; Ashish Ranjan Sharma; Govindasamy Agoramoorthy; Chiranjib Chakraborty; D614G mutation and SARS-CoV-2: impact on S-protein structure, function, infectivity, and immunity. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2021, 105, 9035-9045, 10.1007/s00253-021-11676-2.

- Emma B. Hodcroft; Moira Zuber; Sarah Nadeau; Timothy G. Vaughan; Katharine H. D. Crawford; Christian L. Althaus; Martina L. Reichmuth; John E. Bowen; Alexandra C. Walls; Davide Corti; et al.Jesse D. BloomDavid VeeslerDavid MateoAlberto HernandoIñaki ComasFernando González CandelasTanja StadlerRichard A. NeherSeqCOVID-SPAIN consortium Emergence and spread of a SARS-CoV-2 variant through Europe in the summer of 2020. null 2020, 10, 202106, 10.1101/2020.10.25.20219063.

- Matthew McCallum; Jessica Bassi; Anna De Marco; Alex Chen; Alexandra C. Walls; Julia Di Iulio; M. Alejandra Tortorici; Mary-Jane Navarro; Chiara Silacci-Fregni; Christian Saliba; et al.Kaitlin R. SprouseMaria AgostiniDora PintoKatja CulapSiro BianchiStefano JaconiElisabetta CameroniJohn E. BowenSasha W. TillesMatteo Samuele PizzutoSonja Bernasconi GuastallaGiovanni BonaAlessandra Franzetti PellandaChristian GarzoniWesley C. Van VoorhisLaura E. RosenGyorgy SnellAmalio TelentiHerbert W. VirginLuca PiccoliDavide CortiDavid Veesler SARS-CoV-2 immune evasion by the B.1.427/B.1.429 variant of concern. Science 2021, 373, 648-654, 10.1126/science.abi7994.

- Dandan Tian; Yanhong Sun; Huihong Xu; Qing Ye; The emergence and epidemic characteristics of the highly mutated SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron variant. Journal of Medical Virology 2022, 94, 2376-2383, 10.1002/jmv.27643.

- Yixuan J. Hou; Shiho Chiba; Peter Halfmann; Camille Ehre; Makoto Kuroda; Kenneth H. Dinnon; Sarah R. Leist; Alexandra Schäfer; Noriko Nakajima; Kenta Takahashi; et al.Rhianna E. LeeTeresa M. MascenikRachel GrahamCaitlin E. EdwardsLongping V. TseKenichi OkudaAlena J. MarkmannLuther BarteltAravinda de SilvaDavid M. MargolisRichard C. BoucherScott H. RandellTadaki SuzukiLisa E. GralinskiYoshihiro KawaokaRalph S. Baric SARS-CoV-2 D614G variant exhibits efficient replication ex vivo and transmission in vivo. Science 2020, 370, 1464-1468, 10.1126/science.abe8499.

- Haolin Liu; Qianqian Zhang; Pengcheng Wei; Zhongzhou Chen; Katja Aviszus; John Yang; Walter Downing; Chengyu Jiang; Bo Liang; Lyndon Reynoso; et al.Gregory P. DowneyStephen K. FrankelJohn KapplerPhilippa MarrackGongyi Zhang The basis of a more contagious 501Y.V1 variant of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Research 2021, 31, 720-722, 10.1038/s41422-021-00496-8.

- Bo Meng; Steven A. Kemp; Guido Papa; Rawlings Datir; Isabella A.T.M. Ferreira; Sara Marelli; William T. Harvey; Spyros Lytras; Ahmed Mohamed; Giulia Gallo; et al.Nazia ThakurDami A. CollierPetra MlcochovaLidia M. DuncanAlessandro M. CarabelliJulia C. KenyonAndrew M. LeverAnna De MarcoChristian SalibaKatja CulapElisabetta CameroniNicholas J. MathesonLuca PiccoliDavide CortiLeo C. JamesDavid L. RobertsonDalan BaileyRavindra K. GuptaSamuel C. RobsonNicholas J. LomanThomas R. ConnorTanya GolubchikRocio T. Martinez NunezCatherine LuddenSally CordenIan JohnstonDavid BonsallColin P. SmithAli R. AwanGiselda BuccaM. Estee TorokKordo SaeedJacqui A. PrietoDavid K. JacksonWilliam L. HamiltonLuke B. SnellCatherine MooreEwan M. HarrisonSonia GoncalvesDerek J. FairleyMatthew W. LooseJoanne WatkinsRich LivettSamuel MosesRoberto AmatoSam NichollsMatthew BullDarren L. SmithJeff BarrettDavid M. AanensenMartin D. CurranSurendra ParmarDinesh AggarwalJames G. ShepherdMatthew D. ParkerSharon GlaysherMatthew BashtonAnthony P. UnderwoodNicole PacchiariniKatie F. LovesonKate E. TempletonCordelia F. LangfordJohn SillitoeThushan I. de SilvaDennis WangDominic KwiatkowskiAndrew RambautJustin O’GradySimon CottrellMatthew T.G. HoldenEmma C. ThomsonHusam OsmanMonique AnderssonAnoop J. ChauhanMohammed O. Hassan-IbrahimMara LawniczakAlex AldertonMeera ChandChrystala ConstantinidouMeera UnnikrishnanAlistair C. DarbyJulian A. HiscoxSteve PatersonInigo MartincorenaErik M. VolzAndrew J. PageOliver G. PybusAndrew R. BassettCristina V. ArianiMichael H. Spencer ChapmanKathy K. LiRajiv N. ShahNatasha G. JesudasonYusri TahaMartin P. McHughRebecca DewarAminu S. JahunClaire McMurraySarojini PandeyJames P. McKennaAndrew NelsonGregory R. YoungClare M. McCannScott ElliottHannah LoweBen TempertonSunando RoyAnna PriceSara ReyMatthew WylesStefan RookeSharif ShaabanMariateresa de CesareLaura LetchfordSiona SilveiraEmanuela PelosiEleri Wilson-DaviesMyra HosmilloÁine O’TooleAndrew R. HeskethRichard StarkLouis du PlessisChris RuisHelen AdamsYann BourgeoisStephen L. MichellDimitris GrammatopoulosJonathan EdgeworthJudith BreuerJohn A. ToddChristophe FraserDavid BuckMichaela JohnGemma L. KaySteve PalmerSharon J. PeacockDavid HeyburnDanni WeldonEsther RobinsonAlan McNallyPeter MuirIan B. VipondJohn BoyesVenkat SivaprakasamTranprit SallujaSamir DervisevicEmma J. MeaderNaomi R. ParkKaren OliverAaron R. JeffriesSascha OttAna Da Silva FilipeDavid A. SimpsonChris WilliamsJane A.H. MasoliBridget A. KnightChristopher R. JonesCherian KoshyAmy AshAnna CaseyAndrew BosworthLiz RatcliffeLi Xu-McCraeHannah M. PymontStephanie HutchingsLisa BerryKatie JonesFenella HalsteadThomas DavisChristopher HolmesMiren Iturriza-GomaraAnita O. LucaciPaul Anthony RandellAlison CoxPinglawathee MadonaKathryn Ann HarrisJulianne Rose BrownTabitha W. MahunguDianne Irish-TavaresTanzina HaqueJennifer HartEric WiteleMelisa Louise FentonSteven LiggettClive GrahamEmma SwindellsJennifer CollinsGary EltringhamSharon CampbellPatrick C. McClureGemma ClarkTim J. SloanCarl JonesJessica LynchBen WarneSteven LeonardJillian DurhamThomas WilliamsSam T. HaldenbyNathaniel StoreyNabil-Fareed AlikhanNadine HolmesChristopher MooreMatthew CarlileMalorie PerryNoel CraineRonan A. LyonsAngela H. BeckettSalman GoudarziChristopher FearnKate CookHannah DentHannah PaulRobert DaviesBeth BlaneSophia T. GirgisMathew A. BealeKatherine L. BellisMatthew J. DormanEleanor DruryLeanne KaneSally KaySamantha McGuiganRachel NelsonLiam PrestwoodShavanthi RajatilekaRahul BatraRachel J. WilliamsMark KristiansenAngie GreenAnita JusticeAdhyana I.K. MahanamaBuddhini SamaraweeraNazreen F. HadjirinJoshua QuickRadoslaw PoplawskiLeAnne M. KermackNicola ReynoldsGrant HallYasmin ChaudhryMalte L. PinckertIliana GeorganaRobin J. MollAlicia ThorntonRichard MyersJoanne StocktonCharlotte A. WilliamsWen C. YewAlexander J. TrotterAmy TrebesGeorge MacIntyre-CockettAlec BirchleyAlexander AdamsAmy PlimmerBree Gatica-WilcoxCaoimhe McKerrEmber HilversHannah JonesHibo AsadJason CoombesJohnathan M. EvansLaia FinaLauren GilbertLee GrahamMichelle CroninSara Kumziene-SummerhayesSarah TaylorSophie JonesDanielle C. GrovesPeijun ZhangMarta GallisStavroula F. LoukaIgor StarinskijChris JacksonMarina GourtovaiaGerry Tonkin-HillKevin LewisJaime M. Tovar-CoronaKeith JamesLaura BaxterMohammad T. AlamRichard J. OrtonJoseph HughesSreenu VattipallyManon Ragonnet-CroninFabricia F. NascimentoDavid JorgensenOlivia BoydLily GeidelbergAlex E. ZarebskiJayna RaghwaniMoritz U.G. KraemerJoel SouthgateBenjamin B. LindseyTimothy M. FreemanJon-Paul KeatleyJoshua B. SingerLeonardo De Oliveira MartinsCorin A. YeatsKhalil AbudahabBen E.W. TaylorMirko MenegazzoJohn DaneshWendy HogsdenSahar EldirdiriAnita KenyonJenifer MasonTrevor I. RobinsonAlison HolmesJames PriceJohn A. HartleyTanya CurranAlison E. MatherGiri ShankarRachel JonesRobin HoweSian MorganElizabeth WastengeSiddharth MookerjeeRachael StanleyWendy SmithTimothy PetoDavid EyreDerrick CrookGabrielle VernetChristine KitchenHuw GulliverIan MerrickMartyn GuestRobert MunnDeclan T. BradleyTim WyattCharlotte BeaverLuke FoulserSophie PalmerCarol M. ChurcherEllena BrooksKim S. SmithKaterina GalaiGeorgina M. McManusFrances BoltFrancesc CollLizzie MeadowsStephen W. AttwoodAlisha DaviesElen De LacyFatima DowningSue EdwardsGarry P. ScarlettSarah JeremiahNikki SmithDanielle LeekSushmita SridharSally ForrestClaire CormieHarmeet K. GillJoana DiasEllen E. HigginsonMailis MaesJamie YoungMichelle WantochDorota JamrozyStephanie LoMinal PatelVerity HillClaire M. BewsheaSian EllardCressida AucklandIan HarrisonChloe BishopVicki ChalkerAlex RichterAndrew BeggsAngus BestBenita PercivalJeremy MirzaOliver MegramMegan MayhewLiam CrawfordFiona AshcroftEmma Moles-GarciaNicola CumleyRichard HopesPatawee AsamaphanMarc O. NiebelRory N. GunsonAmanda BradleyAlasdair MacleanGuy MollettRachel BlacowPaul BirdThomas HelmerKarlie FallonJulian TangAntony D. HaleLouissa R. Macfarlane-SmithKatherine L. HarperHolli CardenNicholas W. MachinKathryn A. JacksonShazaad S.Y. AhmadRyan P. GeorgeLance TurtleJoanne WattsCassie BreenAngela CowellAdela Alcolea-MedinaThemoula CharalampousAmita PatelLisa J. LevettJudith HeaneyAileen RowanGraham P. TaylorDivya ShahLaura AtkinsonJack C.D. LeeAdam P. WesthorpeRiaz JannooHelen L. LoweAngeliki KaramaniLeah EnsellWendy ChattertonMonika PusokAshok DadrahAmanda SymmondsGraciela SlugaZoltan MolnarPaul BakerStephen BonnerSarah EssexEdward BartonDebra PadgettGarren ScottJane GreenawayBrendan A.I. PayneShirelle Burton-FanningSheila WaughVeena RaviprakashNicola SheriffVictoria BlakeyLesley-Anne WilliamsJonathan MooreSusanne StonehouseLouise SmithRose K. DavidsonLuke BedfordLindsay CouplandVictoria WrightJoseph G. ChappellTheocharis TsoleridisJonathan BallManjinder KhakhVicki M. FlemingMichelle M. ListerHannah C. Howson-WellsLouise BerryTim BoswellAmelia JosephIona WillinghamNichola DuckworthSarah WalshEmma WiseMatilde MoriNick CortesStephen KiddRebecca WilliamsLaura GiffordKelly BicknellSarah WyllieAllyson LloydRobert ImpeyCassandra S. MaloneBenjamin J. CoggerNick LeveneLynn MonaghanAlexander J. KeeleyDavid G. PartridgeMohammad RazaCariad EvansKate JohnsonEmma BetteridgeBen W. FarrScott GoodwinMichael A. QuailCarol ScottLesley ShirleyScott A.J. ThurstonDiana RajanIraad F. BronnerLouise AigrainNicholas M. RedshawStefanie V. LensingShane McCarthyAlex MakuninCarlos E. BalcazarMichael D. GallagherKathleen A. WilliamsonThomas D. StantonMichelle L. MichelsenJoanna Warwick-DugdaleRobin ManleyAudrey FarbosJames W. HarrisonChristine M. SamblesDavid J. StudholmeAngie LackenbyTamyo MbisaSteven PlattShahjahan MiahDavid BibbyCarmen MansoJonathan HubbGavin DabreraMary RamsayDaniel BradshawUlf SchaeferNatalie GrovesEileen GallagherDavid LeeDavid WilliamsNicholas EllabyHassan HartmanNikos ManesisVineet PatelJuan LedesmaKatherine A. TwohigElias AllaraClare PearsonJeffrey K.J. ChengHannah E. BridgewaterLucy R. FrostGrace Taylor-JoycePaul E. BrownLily TongAlice BroosDaniel MairJenna NicholsStephen N. CarmichaelKatherine L. SmollettKyriaki NomikouElihu Aranday-CortesNatasha JohnsonSeema NickbakhshEdith E. VamosMargaret HughesLucille RainbowRichard EcclesCharlotte NelsonMark WhiteheadRichard GregoryMatthew GemmellClaudia WierzbickiHermione J. WebsterChloe L. FisherAdrian W. SignellGilberto BetancorHarry D. WilsonGaia NebbiaFlavia FlavianiAlberto C. CerdaTammy V. MerrillRebekah E. WilsonMarius CoticNadua BayzidThomas ThompsonErwan AchesonSteven RushtonSarah O’BrienDavid J. BakerSteven RudderAlp AydinFei SangJohnny DebebeSarah FrancoisTetyana I. VasylyevaMarina Escalera ZamudioBernardo GutierrezAngela MarchbankJoshua MaksimovicKarla SpellmanKathryn McCluggageMari MorganRobert BeerSafiah AfifiTrudy WorkmanWilliam FullerCatherine BresnerAdrienn AngyalLuke R. GreenPaul J. ParsonsRachel M. TuckerRebecca BrownMax WhiteleyJames BonfieldChristoph PuetheAndrew WhitwhamJennifier LiddleWill RoweIgor SiveroniThanh Le-VietAmy GaskinRob JohnsonIrina AbnizovaMozam AliLaura AllenRalph AndersonSiobhan Austin-GuestSendu BalaJeffrey BarrettKristina BattledayJames BealSam BellanyTristram BellerbyKatie BellisDuncan BergerMatt BerrimanPaul BevanSimon BinleyJason BishopKirsty BlackburnNick BoughtonSam BowkerTimothy Brendler-SpaethTanya BrooklynSarah Kay BuddenborgRobert BushCatarina CaetanoAlex CaganNicola CarterJoanna CartwrightTiago Carvalho MonteiroLiz ChapmanTracey-Jane ChillingworthPe Recurrent emergence of SARS-CoV-2 spike deletion H69/V70 and its role in the Alpha variant B.1.1.7. Cell Reports 2021, 35, 109292, 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109292.

- Massimo Fabiani; Maria Puopolo; Cristina Morciano; Matteo Spuri; Stefania Spila Alegiani; Antonietta Filia; Fortunato D’Ancona; Martina Del Manso; Flavia Riccardo; Marco Tallon; et al.Valeria ProiettiChiara SaccoMarco MassariRoberto Da CasAlberto Mateo-UrdialesAndrea SidduSerena BattilomoAntonino BellaAnna Teresa PalamaraPatrizia PopoliSilvio BrusaferroGiovanni RezzaFrancesca Menniti IppolitoPatrizio Pezzotti Effectiveness of mRNA vaccines and waning of protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe covid-19 during predominant circulation of the delta variant in Italy: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2022, 376, e069052, 10.1136/bmj-2021-069052.

- Kaixi Ding; Wei Jiang; Chunping Xiong; Ming Lei; Turning point: A new global COVID‐19 wave or a signal of the beginning of the end of the global COVID‐19 pandemic?. Immunity, Inflammation and Disease 2022, 10, e606, 10.1002/iid3.606.

- Vijay Rani Rajpal; Shashi Sharma; Avinash Kumar; Shweta Chand; Lata Joshi; Atika Chandra; Sadhna Babbar; Shailendra Goel; Soom Nath Raina; Behrouz Shiran; et al. “Is Omicron mild”? Testing this narrative with the mutational landscape of its three lineages and response to existing vaccines and therapeutic antibodies. Journal of Medical Virology 2022, 94, 3521-3539, 10.1002/jmv.27749.

- Grigorios D. Amoutzias; Marios Nikolaidis; Eleni Tryfonopoulou; Katerina Chlichlia; Panayotis Markoulatos; Stephen G. Oliver; The Remarkable Evolutionary Plasticity of Coronaviruses by Mutation and Recombination: Insights for the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Future Evolutionary Paths of SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 2022, 14, 78, 10.3390/v14010078.