Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Georgiana Șerban | -- | 2988 | 2022-08-31 17:58:33 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | + 1 word(s) | 2989 | 2022-09-01 03:14:14 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Motataianu, A.; Serban, G.; Barcutean, L.; Balasa, R. Oxidative Stress in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26751 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Motataianu A, Serban G, Barcutean L, Balasa R. Oxidative Stress in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26751. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Motataianu, Anca, Georgiana Serban, Laura Barcutean, Rodica Balasa. "Oxidative Stress in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26751 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Motataianu, A., Serban, G., Barcutean, L., & Balasa, R. (2022, August 31). Oxidative Stress in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26751

Motataianu, Anca, et al. "Oxidative Stress in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis." Encyclopedia. Web. 31 August, 2022.

Copy Citation

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a grievous neurodegenerative disease whose survival is limited to only a few years. In spite of intensive research to discover the underlying mechanisms, the results are fairly inconclusive. Multiple hypotheses have been regarded, including genetic, molecular, and cellular processes. Notably, oxidative stress has been demonstrated to play a crucial role in ALS pathogenesis. In addition to already recognized and exhaustively studied genetic mutations involved in oxidative stress production, exposure to various environmental factors (e.g., electromagnetic fields, solvents, pesticides, heavy metals) has been suggested to enhance oxidative damage.

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

oxidative stress

genetic factors

environmental factors

neurodegeneration

1. Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) etiology is not yet completely understood despite extensive research. Roughly 10% of ALS cases belong to a familial, mainly autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, while the remaining 90% are sporadic forms with no apparent genetic basis [1]. Numerous external occupational and environmental factors have been associated with ALS, including exposure to different chemicals, metals, and pesticides, electromagnetic fields (EMFs), and lifestyle choices, such as smoking and excessive physical exercise [2]. Nevertheless, these factors do not directly cause ALS but act upon various internal susceptibility factors and lead to ALS development. Over 30 mutations have been found to correlate with ALS, particularly its familial form, in genes, such as superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), transactive response (TAR)-DNA binding protein (TARDBP, previously called TDP43), angiogenin (ANG), fused in sarcoma RNA binding protein (FUS), and chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72) [3][4]. ALS is a multifactorial disease caused by various defective cellular and molecular processes, including glutamatergic excitotoxicity, axonal transport, RNA and protein metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress (OS) [3][5][6].

Mitochondria are organelles of great importance in the human body due to their role in converting stored energy into adenosine triphosphate (ATP) via oxidative phosphorylation and phospholipid biogenesis, calcium buffering and regulating programmed cell death [1]. Oxidative phosphorylation is the primary source of free radicals, such as reactive oxygen (ROS), nitrogen (RNS), and sulphur (RSS) species, which are found in all cells but in limited amounts due to the counteracting antioxidant mechanisms [7].

2. OS and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in ALS

OS arises due to disequilibrium caused by excessive ROS production and insufficient compensatory antioxidant systems. The oxygen-free radicals are oxygen species produced by incomplete oxygen reduction in different enzymatic and non-enzymatic cellular processes [8][9]. Mitochondria are the OS mechanism’s primary target and the largest ROS producer [10].

Mitochondria are the primary source of ROS due to their role in ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation, whose significant adverse effect is the production of unpaired electrons [11]. The electron transport chain comprises five multiprotein complexes that mediate the interaction between these electrons and oxygen, creating ROS such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anions (O2−), and hydroxyl radicals (HO−) [9][12]. Mitochondrial complex I (reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide [NADH] coenzyme Q reductase) catalyses the electron transfer from NADH to ubiquinone (coenzyme Q). Ubiquinone also receives electrons from complex II (succinate dehydrogenase). The reduced ubiquinone donates its electrons to complex III (cytochrome bc1) and, eventually, to cytochrome c (cytC). Complex IV (cytC oxidase) participates in the interaction between molecular oxygen and the electrons removed from cytC, leading to water formation [1]. Complexes I, II, and III are the most frequently associated with premature electron leakage to oxygen and play a significant role in ROS production [13].

In addition, increased ROS levels lead to the formation of other reactive species, such as RNS, due to O2− interacting with other molecules, such as nitric oxide, to form peroxynitrite (ONOOˉ). Moreover, in addition to ROS and RNS, mitochondria produce RSS, which are also incredibly reactive. Free oxygen radicals progressively damage proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, resulting in inefficient cellular processes, inflammation, and cell death [1][3]. Mitochondrial internal components and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), in particular, are highly susceptible to OS-induced damage, eventually hindering normal mitochondrial bioenergetics, increasing ROS production and OS [14]. The protective antioxidant systems comprise both enzymatic and non-enzymatic processes. The key enzymes involved in catalytic ROS removal are superoxide dismutases (SODs), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidases (GPXs), glutathione reductase (GR), and thioredoxin (TRX). In addition, the non-enzymatic complexes primarily comprise vitamins A, C, and E, glutathione (GSH), and proteins such as albumin and ceruloplasmin [9][15].

Abnormally high free radical levels and low antioxidant systems represent a universally accepted yet incompletely understood pathological ALS characteristic. OS unquestionably plays a crucial role in motor neuron death, but the precise timing of oxidative damage remains unknown [16]. OS biomarkers have been identified in ALS patients’ brain tissue, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), blood, and urine [17]. Because the life expectancy of ALS patients is relatively short, it is impossible to monitor OS biomarkers over an extended period. Moreover, it is challenging to determine whether OS is a cause of ALS-associated neurodegeneration or a consequence of other underlying etiologic factors because of its sporadic o nset and the current lack of methods to predict ALS development [8]. Studies with a murine ALS model have found modified mitochondrial structures and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway activation, which generally occurs due to OS-induced damage and stimulates the formation of intracellular antioxidant molecules, during early ALS stages, implying OS involvement in the initial phase of ALS [18][19].

However, these studies used the murine mutant SOD1 ALS model, and SOD1 mutations only account for 20% of human familial ALS cases. Babu et al. [20] found a significant increase in lipid peroxidation and decreases in antioxidant enzymes CAT, GR, GSH, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) in the erythrocytes of 20 sporadic ALS patients. The changes progressed alongside ALS pathogenesis, consistent with OS involvement in ALS development. Furthermore, the abovementioned environmental and occupational risk factors mutually stimulate and induce pro-oxidative states, which can eventually adversely affect motor neurons [21].

Coiled-coil-helix-coiled-coil-helix domain-containing protein 10 (CHCHD10) is a mitochondrial protein located in the intermembrane space (IMS) with no recognised function [22]. However, it is believed to be involved in maintaining mitochondrial cristae morphology and proper oxidative phosphorylation. Overexpression of mutant CHCHD10 containing an allele associated with ALS leads to altered mitochondrial structure and defective electron transport chain activity, particularly in multiprotein complexes I, II, III, and IV [23][24]. Moreover, fibroblasts had mitochondrial ultrastructural damage and mitochondrial network fragmentation in an ALS patient carrying a CHCHD10 mutation [23].

3. Genetic Variants and OS

3.1. SOD1 Mutations

SOD1 is located on chromosome 21 and encodes an important intracellular antioxidant enzyme. SOD1 is found mainly in the cytosol, with approximately 5% of total cellular SOD1 found in the mitochondrial IMS. It primarily converts the O2− into H2O2, which is then converted to water and oxygen by other antioxidant enzymes, such as CAT, GPXs, and peroxiredoxin [25]. An alternative process for removing primary ROS is detoxification by cytC, the main advantage of which is the absence of secondary ROS. However, its major drawback is its interaction with H2O2 resulting from SOD1 activity (cytochrome peroxidation), leading to a highly reactive molecule, oxoferryl-cytC [25].

To adequately fulfil its function, SOD1 must reach a mature, highly stable form via complex post-translational modifications (PTMs) facilitated by a copper chaperone for SOD1 (CCS) [26]. PTMs include zinc and copper metal binding, disulphide bond formation and folding, and exposure of hydrophobic regions for further dimerisation [1]. Cytosolic SOD1 can traverse the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) through the translocase of outer membrane (TOM). Its return is prevented by CCS-mediated establishing disulphide bonds and inserting metal ions [1]. CCS distribution influences SOD1 localisation. Cytosolic CCS impedes SOD1 mitochondrial import, while mitochondrial CCS prevents SOD1 cytosolic export. Moreover, it acts as an oxygen sensor. Hyperoxia maintains cytosolic CCS, while hypoxia promotes the mitochondrial import of CCS and SOD1 [26]. Therefore, increased mitochondrial respiratory chain activity, CCS intra-mitochondrial translocation, and SOD1 maturation under hypoxia act as a compensatory antioxidant system [3]. In addition, the Mia40/Erv1 pathway participates in CCS mitochondrial import in a respiratory chain-dependent manner [26].

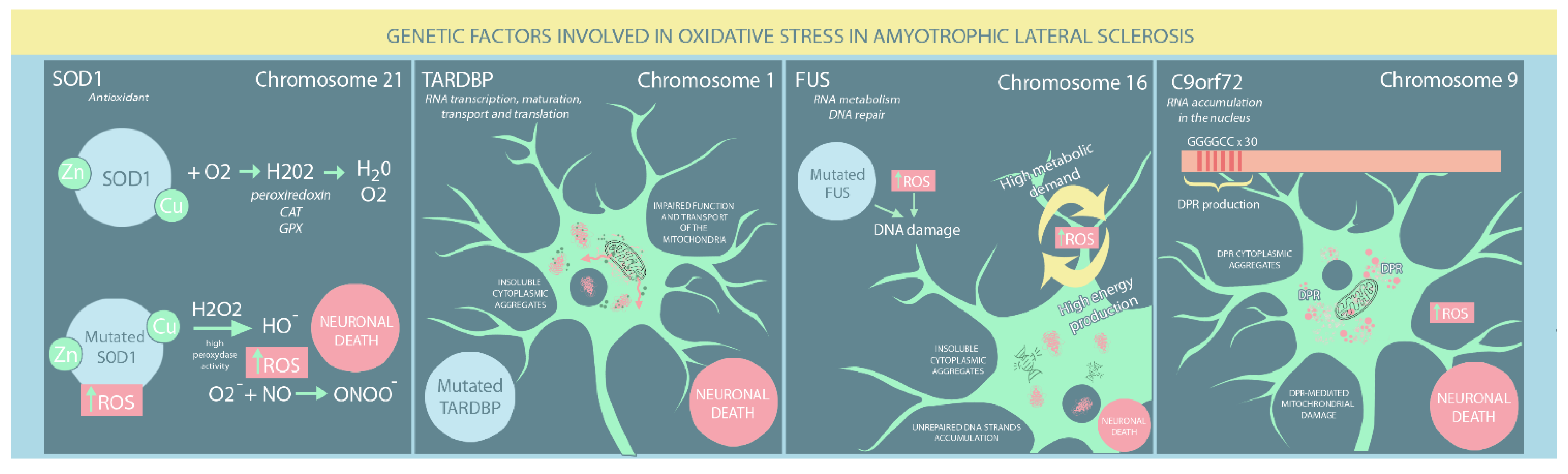

SOD1 has been implicated in ALS pathogenesis, with more than 160 mutations so far identified that typically change only a single amino acid. However, the exact mechanism leading to motor neuron death remains to be determined. While SOD1 mutations are primarily found in familial ALS cases, they likely also contribute to sporadic ALS [27]. Notably, mitochondrial accumulation of mutant SOD1 protein is characterised by increased enzymatic function, which appears to cause neurodegeneration [21][27][28][29]. However, the precise mechanisms of SOD1 toxicity are not fully understood. Nevertheless, several hypotheses have been proposed. SOD1 has a low level of intrinsic peroxidase activity, which can be amplified by high ROS levels [30]. SOD1 containing the Av5, H48Q, and G93A mutations has enhanced peroxidase activity and catalyses H2O2 conversion to HOˉ, irreversibly inactivating the dismutase structure [30]. Furthermore, O2− shows a higher propensity for nitric oxide than mutant SOD1, leading to ONOOˉ production with further tyrosine nitration of cellular proteins, resulting in neuronal death [8][31]. SOD1 maturation is a complex process and is highly susceptible to disruption. Numerous amino acid mutations affecting metal binding or disulphide bridge formation lead to misfolded proteins, each of whose structure is unstable and inclined to create insoluble SOD1 aggregates. However, mutant SOD1 cannot adequately respond to CCS-induced PTMs, eluding the maturation process essential for normal function and enhancing intracellular ROS accumulation [32]. A negative feedback cycle occurs in which OS and mitochondrial damage caused by misfolded SOD1 lead to further SOD1 misfolding and further mitochondrial damage [1]. However, mutant SOD1 aggregates interact with OMM proteins involved in mitochondrial apoptosis, such as Bcl12 and voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), activating pro-apoptotic pathways. Regardless of the mechanisms involved, motor neuron death results [3][33] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Genetic risk factors involved in oxidative stress in ALS patients. (SOD: superoxide dismutase; ROS: reactive oxygen species; DPR: dipeptide repeat proteins).

3.2. TARDBP Mutation

TARDBP, also known as TDP-43, is located on chromosome 1 and encodes a ubiquitous heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein comprising four domains: two RNA highly conserved recognition motifs essential for its role in protein biogenesis, a C-terminal glycine-enriched low complexity domain (LCD) involved in protein-protein interactions, and an N-terminal region whose function remains contentious [34][35]. It has various functions, particularly in RNA transcription, maturation, transport and translation, and plays a crucial role in intracellular stress management. TARDBP participates in the biogenesis and maintenance of stress granules, small membrane-less structures that form due to cellular exposure to stress and protect RNA and its associated ribonucleoproteins [36]. Moreover, TARDBP interacts with numerous proteins involved in diverse physiological processes, such as RNA metabolism, the immune response, and stress-induced pathways [37].

Almost 10% of ALS familial cases are associated with TARDBP mutations, which mostly affect its LCD. The key properties of mutated TARDBP include an increased tendency to aggregate, cytoplasmic mislocalisation, unstable structure, protease resistance, and altered protein-protein interactions [38][39]. Furthermore, patients with sporadic ALS frequently have elevated TARDBP levels within neuronal and cytoplasmic inclusions, a current hallmark of ALS pathogenesis [39]. Altered cellular redox balance has also been suggested as a causal factor in ALS pathogenesis. Several studies have demonstrated a reciprocal relationship between OS and TARDBP mutations: whereas TDP-43 mutations impair mitochondria, OS production greatly increases TDP-43 toxicity [40][41]. On the one hand, Cohen et al. [42] showed that OS induces cysteine disulphide cross-linking in TARDBP, decreasing protein solubility and enhancing the formation of insoluble cytoplasmic aggregates. More recently, OS was found to promote the acetylation of lysine-145, particularly in cytoplasmic TARDBP, leading to its aggregation, LCD hyperphosphorylation, and loss of normal TARDBP function [43]. On the other hand, Magrane et al. [44] have shown that mutated TARDBP (A315T) overexpression impairs mitochondrial structure and transport. Conversely, Wang [45] showed that both wildtype and mutated TARDBP (Q331K and M337V) reduced mitochondrial density in neuritis and mitochondrial dynamics. Altered mitochondrial function can enhance TARDBP aggregation through reduced GSH levels, leading to unbalanced ROS overproduction and neurodegeneration. Moreover, several studies have found that mutated TARDBP markedly decreased the antioxidant expression of Nrf2, further enhancing OS [42][43][46][47] (Figure 1).

3.3. FUS Mutation

FUS is located on chromosome 16 and encodes a member of the RNA/DNA-binding protein family that comprises two main domains: an N-terminal LCD region involved in transcriptional activation and a C-terminal region implicated in RNA and protein binding [48]. Similar to TARDBP, most mutations occur within the last 12 amino acids of the C-terminal region, particularly in familial ALS forms. However, N-terminal domain mutations are often associated with sporadic ALS [49]. Patients with FUS mutations typically develop juvenile ALS, with onset before the age of 40 years [48]. Due to its nucleic acid binding capacity, FUS is implicated in RNA metabolism and DNA repair [50].

FUS and TARDBP share similar molecular mechanisms that lead to ALS occurrence, both involving the cytosolic accumulation of protein aggregates that are a hallmark of ALS [49]. Nevertheless, FUS has been found to cause ALS by a DNA-related process. Due to their high metabolic demands, neurons are characterised by intense energy production, with a detrimental elevation in ROS, which is harmful to DNA. Wang et al. [50] showed that FUS mutants, particularly R521H and P525L, failed to mend OS-induced DNA damage properly. Consequently, significant numbers of unrepaired DNA strand breaks accumulate in the neurons, eventually leading to motor neuron death (Figure 1).

4. Environmental Factors Associated with OS in ALS

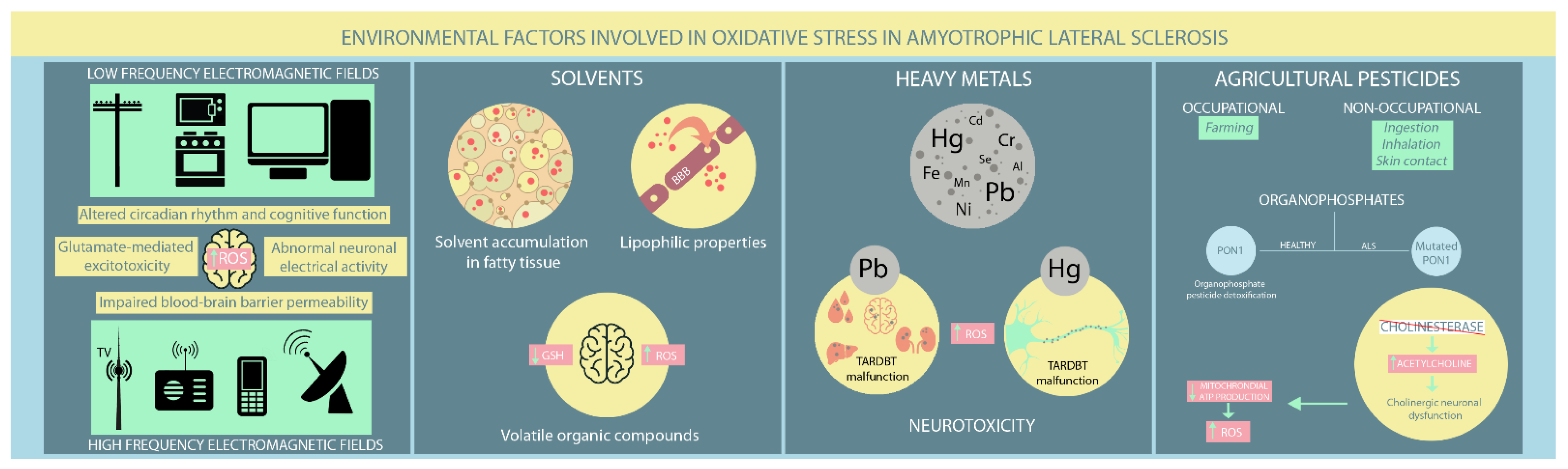

Already recognised and exhaustively studied mutations can no longer thoroughly explain ALS pathogenesis. Exposure to various environmental factors, such as EMFs, solvents, heavy metals, and agricultural pesticides, has been hypothesised to contribute to ALS pathogenesis. Nevertheless, the contribution of several occupational factors to ALS has proven difficult to assess since there are no clear signs indicative of ALS development in ostensibly healthy individuals. Therefore, exposure to various environmental factors is based solely on patient recollection, and existing studies have provided controversial evidence that has not clarified the role of environmental factors in ALS (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Environmental risk factors involved in oxidative stress in ALS patients. (ROS: reactive oxygen species; Hg: mercury; Pb: lead; Cd: cadmium; Cr: chromium; Se: selenium; Fe: iron; Mn: manganese; Ni: nickel).

4.1. EMFs

EMFs occur naturally and are ever present in people’s lives. However, environmental exposure has increased lately due to the rapid development of artificial EMF sources [51]. There are generally two EMF types: low frequency (LF-EMF) from power lines, household electrical appliances, and computers, and high frequency (HF-EMF) from radars, radios, mobile phones, and television broadcast towers [51]. Most studies have focused on the LF-EMF but provide conflicting results regarding LF-EMF-induced neurodegeneration. A Swedish meta-analysis found a potential positive association between LF-EMF exposure and ALS occurrence. However, they could not discriminate between isolated and occupational LF-EMF exposure [52]. An updated study by the same group found that LF-EMF occupational exposure carries an absolute risk for ALS [53]. A prospective study that followed patients for 17.3 years found a positive exposure-dependant association between occupational exposure to shallow frequency magnetic fields and ALS mortality [54]. An Italian study further supports these findings, confirming the predisposing effect of the proximity to overhead power lines on increasing ALS risk [55]. However, a Dutch study found no elevated risk of ALS development in people living near LF-EMF sources [56]. Therefore, these studies should be interpreted cautiously, as their correlations are based broadly on registry data, which is much more susceptible to bias [57][58]. Evidence for HF-EMFs is limited. Luna et al. [51] performed an epidemiological study that hypothesised a potential association between HF-EMF exposure from mobile communication antennas and ALS occurrence. However, further studies are needed to confirm or refute these findings.

The pathological implications of EMF exposure on the nervous system remain under investigation. Various neurological effects have been reported, such as disturbances in circadian rhythm, altered cognitive function, abnormal neuronal electrical activity, modified neurotransmitters release (e.g., glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity), elevated ROS production, and impaired blood-brain barrier permeability [51][59]. Both in vivo and in vitro studies have found that EMF-induced OS significantly influences different cellular processes, including gene dysregulation, abnormal protein aggregation, and neuroinflammation, which all have established roles in ALS [57][58][59][60]. Several studies have reported a substantial deterioration in antioxidant defence mechanisms in aged rats exposed to LF-EMF [61][62][63]. Moreover, exposure to high LF-EMF leads to neurological effects consequent not only to lipid peroxidation, but also to disturbances in several molecular processes, such as iron-related gene dysregulation in SOD1 mouse mutant models [63][64]. Other murine studies on mutant SOD1 have found no apparent EMF effect on ALS onset and survival. However, motor performances appeared worse after exposure compared to unexposed controls [61][65].

4.2. Solvents

Solvents are increasingly present in modern society due to their inclusion in different industrial and household products, such as paints, adhesives, and cleaning solutions. They can penetrate the blood-brain barrier through their lipophilic properties and cause various neurological disturbances, from cognitive impairment to motor deficits. Moreover, solvents accumulate within fatty tissues with recurrent exposure and continue to damage nerve function [66][67]. While solvents have gained increasing recognition as ALS inducers, findings on the relationship between solvent exposure and ALS pathogenesis have been contradictory. Koeman et al. [54] disproved any potential connection between ALS and aromatic and chlorinated solvents. However, a Swedish case-control study [68] found an inverse association between methylene chloride exposure, a common solvent with known carcinogenic effects in humans, and ALS risk in people younger than 65, contrasting with a previous study [69] that found no connection between them. Formaldehyde exposure, particularly among healthcare workers, has provided conflicting results. Some studies support its role in increasing ALS risk, particularly in males [68][70][71], while another study found little or no association [69]. However, a positive association between aromatic solvents and ALS was reported by Malek et al. [72]. Moreover, Andrew et al. [73] concluded that higher solvent exposure increased ALS risk in industrial employees, consistent with the findings of Malek et al. in a residential setting [74].

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs), particularly toluene and xylene, are most frequently implicated in impairing central nervous system (CNS) function. Their primary pathological mechanism is OS due to GSH depletion [66][75]. Studies have shown that GSH levels decrease as ALS progresses, supporting the hypothesis that VOC exposure might contribute to inducing latent ALS [66][76][77][78]. Organic solvents also deplete mitochondrial ATP, leading to abnormal functioning of ATP-dependent cellular processes and eventually apoptosis [66][79]. Constant VOC exposure is associated with increased neuronal excitation. Given the already recognised involvement of motor neuron hyperexcitability in ALS pathogenesis, the latter mechanism supports the potential role of VOCs in ALS progression [66][80]. Furthermore, toluene exposure has been shown to intervene in axonal transport by reducing levels of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), leading to the loss of anterior horn neurons in ALS patients [66][81][82][83].

References

- Smith, E.F.; Shaw, P.J.; De Vos, K.J. The role of mitochondria in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 710, 132933.

- Ingre, C.; Roos, P.M.; Piehl, F.; Kamel, F.; Fang, F. Risk factors for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Epidemiol. 2015, 7, 181–193.

- Greco, V.; Longone, P.; Spalloni, A.; Pieroni, L.; Urbani, A. Crosstalk Between Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Damage: Focus on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1158, 71–82.

- Van Es, M.A.; Hardiman, O.; Chio, A.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Pasterkamp, R.J.; Veldink, J.H.; van den Berg, L.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 2017, 390, 2084–2098.

- Turner, M.R.; Hardiman, O.; Benatar, M.; Brooks, B.R.; Chio, A.; de Carvalho, M.; Ince, P.G.; Lin, C.; Miller, R.G.; Mitsumoto, H.; et al. Controversies and priorities in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 310–322.

- Valko, K.; Ciesla, L. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Prog. Med. Chem. 2019, 58, 63–117.

- Sbodio, J.I.; Snyder, S.H.; Paul, B.D. Redox Mechanisms in Neurodegeneration: From Disease Outcomes to Therapeutic Opportunities. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2019, 30, 1450–1499.

- Cunha-Oliveira, T.; Montezinho, L.; Mendes, C.; Firuzi, O.; Saso, L.; Oliveira, P.J.; Silva, F.S.G. Oxidative Stress in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Pathophysiology and Opportunities for Pharmacological Intervention. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 15, 5021694.

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763.

- Carrì, M.T.; Valle, C.; Bozzo, F.; Cozzolino, M. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage: Importance in non-SOD1 ALS. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2015, 9, 41.

- Kausar, S.; Wang, F.; Cui, H. The Role of Mitochondria in Reactive Oxygen Species Generation and Its Implications for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2018, 7, 274.

- Murphy, M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009, 417, 1–13.

- Brand, M.D. The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp. Gerontol. 2010, 45, 466–472.

- Cui, H.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, H. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. J. Signal. Transduct. 2012, 2012, 646354.

- Niedzielska, E.; Smaga, I.; Gawlik, M.; Moniczewski, A.; Stankowicz, P.; Pera, J.; Filip, M. Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 4094–4125.

- Agar, J.; Durham, H. Relevance of oxidative injury in the pathogenesis of motor neuron diseases. Amyotroph. Lateral. Scler. Other Motor. Neuron. Disord. 2003, 4, 232–242.

- Singh, A.; Kukreti, R.; Saso, L.; Kukreti, S. Oxidative Stress: A Key Modulator in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2019, 24, 1583.

- Vande Velde, C.; McDonald, K.K.; Boukhedimi, Y.; McAlonis-Downes, M.; Lobsiger, C.S.; Bel Hadj, S.; Zandona, A.; Julien, J.P.; Shah, S.B.; Cleveland, D.W. Misfolded SOD1 associated with motor neuron mitochondria alters mitochondrial shape and distribution prior to clinical onset. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22031.

- Kraft, A.D.; Resch, J.M.; Johnson, D.A.; Johnson, J.A. Activation of the Nrf2-ARE pathway in muscle and spinal cord during ALS-like pathology in mice expressing mutant SOD1. Exp. Neurol. 2007, 207, 107–117.

- Babu, G.N.; Kumar, A.; Chandra, R.; Puri, S.K.; Singh, R.L.; Kalita, J.; Misra, U.K. Oxidant-antioxidant imbalance in the erythrocytes of sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients correlates with the progression of disease. Neurochem. Int. 2008, 52, 1284–1289.

- D’Amico, E.; Factor-Litvak, P.; Santella, R.M.; Mitsumoto, H. Clinical perspective on oxidative stress in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 509–527.

- Anderson, C.J.; Bredvik, K.; Burstein, S.R.; Davis, C.; Meadows, S.M.; Dash, J.; Case, L.; Milner, T.A.; Kawamata, H.; Zuberi, A.; et al. ALS/FTD mutant CHCHD10 mice reveal a tissue-specific toxic gain-of-function and mitochondrial stress response. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 138, 103–121.

- Bannwarth, S.; Ait-El-Mkadem, S.; Chaussenot, A.; Genin, E.C.; Lacas-Gervais, S.; Fragaki, K.; Berg-Alonso, L.; Kageyama, Y.; Serre, V.; Moore, D.G.; et al. A mitochondrial origin for frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis through CHCHD10 involvement. Brain 2014, 137 Pt. 8, 2329–2345.

- Genin, E.C.; Plutino, M.; Bannwarth, S.; Villa, E.; Cisneros-Barroso, E.; Roy, M.; Ortega-Vila, B.; Fragaki, K.; Lespinasse, F.; Pinero-Martos, E.; et al. CHCHD10 mutations promote loss of mitochondrial cristae junctions with impaired mitochondrial genome maintenance and inhibition of apoptosis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 58–72.

- Vehviläinen, P.; Koistinaho, J.; Gundars, G. Mechanisms of mutant SOD1 induced mitochondrial toxicity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014, 8, 126.

- Kawamata, H.; Manfredi, G. Different regulation of wild-type and mutant Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase localization in mammalian mitochondria. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, 3303–3317.

- Tafuri, F.; Ronchi, D.; Magri, F.; Comi, G.P.; Corti, S. SOD1 misplacing and mitochondrial dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis pathogenesis. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2015, 9, 336.

- Sasaki, S.; Warita, H.; Murakami, T.; Shibata, N.; Komori, T.; Abe, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Iwata, M. Ultrastructural study of aggregates in the spinal cord of transgenic mice with a G93A mutant SOD1 gene. Acta Neuropathol. 2005, 109, 247–255.

- Higgins, C.M.; Jung, C.; Ding, H.; Xu, Z. Mutant Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase that causes motoneuron degeneration is present in mitochondria in the CNS. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, RC215.

- Hitchler, M.J.; Domann, F.E. Regulation of CuZnSOD and its redox signaling potential: Implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2014, 20, 1590–1598.

- Barber, S.C.; Mead, R.J.; Shaw, P.J. Oxidative stress in ALS: A mechanism of neurodegeneration and a therapeutic target. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1762, 1051–1067.

- Carroll, M.C.; Outten, C.E.; Proescher, J.B.; Rosenfeld, L.; Watson, W.H.; Whitson, L.J.; Hart, P.J.; Jensen, L.T.; Cizewski Culotta, V. The effects of glutaredoxin and copper activation pathways on the disulfide and stability of Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 28648–28656.

- Pasinelli, P.; Belford, M.E.; Lennon, N.; Bacskai, B.J.; Hyman, B.T.; Trotti, D.; Brown, R.H., Jr. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated SOD1 mutant proteins bind and aggregate with Bcl-2 in spinal cord mitochondria. Neuron 2004, 43, 19–30.

- Feneberg, E.; Gordon, D.; Thompson, A.G.; Finelli, M.J.; Dafinca, R.; Candalija, A.; Charles, P.D.; Mäger, I.; Wood, M.J.; Fischer, R.; et al. An ALS-linked mutation in TDP-43 disrupts normal protein interactions in the motor neuron response to oxidative stress. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 144, 105050.

- Afroz, T.; Hock, E.M.; Ernst, P.; Foglieni, C.; Jambeau, M.; Gilhespy, L.A.B.; Laferriere, F.; Maniecka, Z.; Plückthun, A.; Mittl, P.; et al. Functional and dynamic polymerization of the ALS-linked protein TDP-43 antagonizes its pathologic aggregation. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 45.

- Aulas, A.; Vande Velde, C. Alterations in stress granule dynamics driven by TDP-43 and FUS: A link to pathological inclusions in ALS? Front. Cell Neurosci. 2015, 9, 423.

- Blokhuis, A.M.; Koppers, M.; Groen, E.J.N.; van den Heuvel, D.M.A.; Dini Modigliani, S.; Anink, J.J.; Fumoto, K.; van Diggelen, F.; Snelting, A.; Sodaar, P.; et al. Comparative interactomics analysis of different ALS-associated proteins identifies converging molecular pathways. Acta. Neuropathol. 2016, 132, 175–196.

- Buratti, E. Functional Significance of TDP-43 Mutations in Disease. Adv. Genet. 2015, 91, 1–53.

- Prasad, A.; Bharathi, V.; Sivalingam, V.; Girdhar, A.; Patel, B.K. Molecular Mechanisms of TDP-43 Misfolding and Pathology in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 25.

- Park, S.K.; Park, S.; Liebman, S.W. Respiration Enhances TDP-43 Toxicity, but TDP-43 Retains Some Toxicity in the Absence of Respiration. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 2050–2059.

- Gautam, M.; Jara, J.H.; Kocak, N.; Rylaarsdam, L.E.; Kim, K.D.; Bigio, E.H.; Hande Özdinler, P. Mitochondria, ER, and nuclear membrane defects reveal early mechanisms for upper motor neuron vulnerability with respect to TDP-43 pathology. Acta. Neuropathol. 2019, 137, 47–69.

- Cohen, T.J.; Hwang, A.W.; Unger, T.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M. Redox signalling directly regulates TDP-43 via cysteine oxidation and disulphide cross-linking. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 1241–1252.

- Cohen, T.J.; Hwang, A.W.; Restrepo, C.R.; Yuan, C.X.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M. An acetylation switch controls TDP-43 function and aggregation propensity. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5845.

- Magrané, J.; Cortez, C.; Gan, W.B.; Manfredi, G. Abnormal mitochondrial transport and morphology are common pathological denominators in SOD1 and TDP43 ALS mouse models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 1413–1424.

- Wang, W.; Li, L.; Lin, W.L.; Dickson, D.W.; Petrucelli, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. The ALS disease-associated mutant TDP-43 impairs mitochondrial dynamics and function in motor neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 4706–4719.

- Duan, W.; Li, X.; Shi, J.; Guo, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, C. Mutant TAR DNA-binding protein-43 induces oxidative injury in motor neuron-like cell. Neuroscience 2010, 169, 1621–1629.

- Tian, Y.P.; Che, F.Y.; Su, Q.P.; Lu, Y.C.; You, C.P.; Huang, L.M.; Wang, S.G.; Wang, L.; Yu, J.X. Effects of mutant TDP-43 on the Nrf2/ARE pathway and protein expression of MafK and JDP2 in NSC-34 cells. Genet. Mol. Res. 2017, 16, gmr16029638.

- Shang, Y.; Huang, E.J. Mechanisms of FUS mutations in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Res. 2016, 1647, 65–78.

- Lattante, S.; Rouleau, G.A.; Kabashi, E. TARDBP and FUS mutations associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Summary and update. Hum. Mutat. 2013, 34, 812–826.

- Wang, H.; Guo, W.; Mitra, J.; Hegde, P.M.; Vandoorne, T.; Eckelmann, B.J.; Mitra, S.; Tomkinson, A.E.; Van Den Bosch, L.; Hegde, M.L. Mutant FUS causes DNA ligation defects to inhibit oxidative damage repair in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3683.

- Luna, J.; Leleu, J.P.; Preux, P.M.; Corcia, P.; Couratier, P.; Marin, B.; Boumediene, F.; Fralim Consortium. Residential exposure to ultra high frequency electromagnetic fields emitted by Global System for Mobile (GSM) antennas and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis incidence: A geo-epidemiological population-based study. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108525.

- Gunnarsson, L.G.; Bodin, L. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Occupational Exposures: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2018, 15, 2371.

- Gunnarsson, L.G.; Bodin, L. Occupational Exposures and Neurodegenerative Diseases-A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2019, 16, 337.

- Koeman, T.; Slottje, P.; Schouten, L.J.; Peters, S.; Huss, A.; Veldink, J.H.; Kromhout, H.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Vermeulen, R. Occupational exposure and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a prospective cohort. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 578–585.

- Filippini, T.; Tesauro, M.; Fiore, M.; Malagoli, C.; Consonni, M.; Violi, F.; Iacuzio, L.; Arcolin, E.; Oliveri Conti, G.; Cristaldi, A.; et al. Environmental and Occupational Risk Factors of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2020, 17, 2882.

- Seelen, M.; Vermeulen, R.C.; van Dillen, L.S.; van der Kooi, A.J.; Huss, A.; de Visser, M.; van den Berg, L.H.; Veldink, J.H. Residential exposure to extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields and the risk of ALS. Neurology 2014, 83, 1767–1769.

- Riancho, J.; Sanchez de la Torre, J.R.; Paz-Fajardo, L.; Limia, C.; Santurtun, A.; Cifra, M.; Kourtidis, K.; Fdez-Arroyabe, P. The role of magnetic fields in neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2021, 65, 107–117.

- Capozzella, A.; Sacco, C.; Chighine, A.; Loreti, B.; Scala, B.; Casale, T.; Sinibaldi, F.; Tomei, G.; Giubilati, R.; Tomei, F.; et al. Work related etiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): A meta-analysis. Ann. Ig. 2014, 26, 456–472.

- Consales, C.; Merla, C.; Marino, C.; Benassi, B. Electromagnetic fields, oxidative stress, and neurodegeneration. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 2012, 683897.

- Poulletier de Gannes, F.; Ruffié, G.; Taxile, M.; Ladevèze, E.; Hurtier, A.; Haro, E.; Duleu, S.; Charlet de Sauvage, R.; Billaudel, B.; Geffard, M.; et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and extremely-low frequency (ELF) magnetic fields: A study in the SOD-1 transgenic mouse model. Amyotroph. Lateral. Scler. 2009, 10, 370–373.

- Filippini, T.; Hatch, E.E.; Vinceti, M. Residential exposure to electromagnetic fields and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A dose-response meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11939.

- Falone, S.; Mirabilio, A.; Carbone, M.C.; Zimmitti, V.; Di Loreto, S.; Mariggiò, M.A.; Mancinelli, R.; Di Ilio, C.; Amicarelli, F. Chronic exposure to 50 Hz magnetic fields causes a significant weakening of antioxidant defence systems in aged rat brain. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 2762–2770.

- Jelenković, A.; Janać, B.; Pesić, V.; Jovanović, D.M.; Vasiljević, I.; Prolić, Z. Effects of extremely low-frequency magnetic field in the brain of rats. Brain. Res. Bull. 2006, 68, 355–360.

- Oshiro, S.; Morioka, M.S.; Kikuchi, M. Dysregulation of iron metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 2011, 378278.

- Liebl, M.P.; Windschmitt, J.; Besemer, A.S.; Schäfer, A.K.; Reber, H.; Behl, C.; Clement, A.M. Low-frequency magnetic fields do not aggravate disease in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8585.

- Ratner, M.H.; Jabre, J.F.; Ewing, W.M.; Abou-Donia, M.; Oliver, L.C. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—A case report and mechanistic review of the association with toluene and other volatile organic compounds. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2018, 61, 251–260.

- Dickerson, A.S.; Hansen, J.; Thompson, S.; Gredal, O.; Weisskopf, M.G. A mixtures approach to solvent exposures and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A population-based study in Denmark. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 241–249.

- Peters, T.L.; Kamel, F.; Lundholm, C.; Feychting, M.; Weibull, C.E.; Sandler, D.P.; Wiebert, P.; Sparén, P.; Ye, W.; Fang, F. Occupational exposures and the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 87–92.

- Fang, F.; Quinlan, P.; Ye, W.; Barber, M.K.; Umbach, D.M.; Sandler, D.P.; Kamel, F. Workplace exposures and the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Environ. Health. Perspect. 2009, 117, 1387–1392.

- Roberts, A.L.; Johnson, N.J.; Cudkowicz, M.E.; Eum, K.D.; Weisskopf, M.G. Job-related formaldehyde exposure and ALS mortality in the USA. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2016, 87, 786–788.

- Weisskopf, M.G.; Morozova, N.; O’Reilly, E.J.; McCullough, M.L.; Calle, E.E.; Thun, M.J.; Ascherio, A. Prospective study of chemical exposures and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2009, 80, 558–561.

- Malek, A.M.; Barchowsky, A.; Bowser, R.; Youk, A.; Talbott, E.O. Pesticide exposure as a risk factor for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A meta-analysis of epidemiological studies: Pesticide exposure as a risk factor for ALS. Environ. Res. 2012, 117, 112–119.

- Andrew, A.S.; Caller, T.A.; Tandan, R.; Duell, E.J.; Henegan, P.L.; Field, N.C.; Bradley, W.G.; Stommel, E.W. Environmental and Occupational Exposures and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in New England. Neurodegener. Dis. 2017, 17, 110–116.

- Malek, A.M.; Barchowsky, A.; Bowser, R.; Heiman-Patterson, T.; Lacomis, D.; Rana, S.; Youk, A.; Talbott, E.O. Exposure to hazardous air pollutants and the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 197, 181–186.

- Georgieva, T.; Michailova, A.; Panev, T.; Popov, T. Possibilities to control the health risk of petrochemical workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2002, 75, S21–S26.

- Cheong, I.; Marjańska, M.; Deelchand, D.K.; Eberly, L.E.; Walk, D.; Öz, G. Ultra-High Field Proton MR Spectroscopy in Early-Stage Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 42, 1833–1844, Erratum in 2017, 42, 1845–1846.

- Foerster, B.R.; Pomper, M.G.; Callaghan, B.C.; Petrou, M.; Edden, R.A.; Mohamed, M.A.; Welsh, R.C.; Carlos, R.C.; Barker, P.B.; Feldman, E.L. An imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis revealed by use of 3-T proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. JAMA. Neurol. 2013, 70, 1009–1016.

- Weiduschat, N.; Mao, X.; Hupf, J.; Armstrong, N.; Kang, G.; Lange, D.J.; Mitsumoto, H.; Shungu, D.C. Motor cortex glutathione deficit in ALS measured in vivo with the J-editing technique. Neurosci. Lett. 2014, 570, 102–107.

- Myhre, O.; Fonnum, F. The effect of aliphatic, naphthenic, and aromatic hydrocarbons on production of reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species in rat brain synaptosome fraction: The involvement of calcium, nitric oxide synthase, mitochondria, and phospholipase A. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001, 62, 119–128.

- Mills, K.R.; Nithi, K.A. Corticomotor threshold is reduced in early sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 1997, 20, 1137–1141.

- Kikuchi, H.; Doh-ura, K.; Kawashima, T.; Kira, J.; Iwaki, T. Immunohistochemical analysis of spinal cord lesions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) antibodies. Acta Neuropathol. 1999, 97, 13–21.

- Farah, C.A.; Nguyen, M.D.; Julien, J.P.; Leclerc, N. Altered levels and distribution of microtubule-associated proteins before disease onset in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurochem. 2003, 84, 77–86.

- Gotohda, T.; Tokunaga, I.; Kitamura, O.; Kubo, S. Toluene inhalation induced neuronal damage in the spinal cord and changes of neurotrophic factors in rat. Leg. Med. 2007, 9, 123–127.

More

Information

Subjects:

Neurosciences

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.0K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

01 Sep 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No