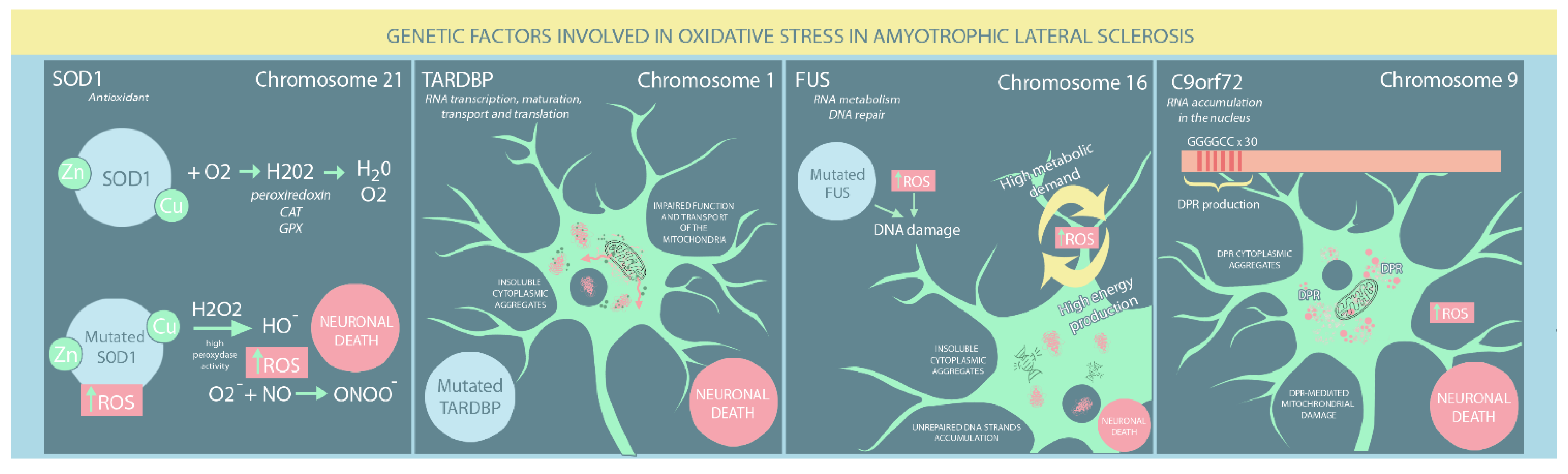

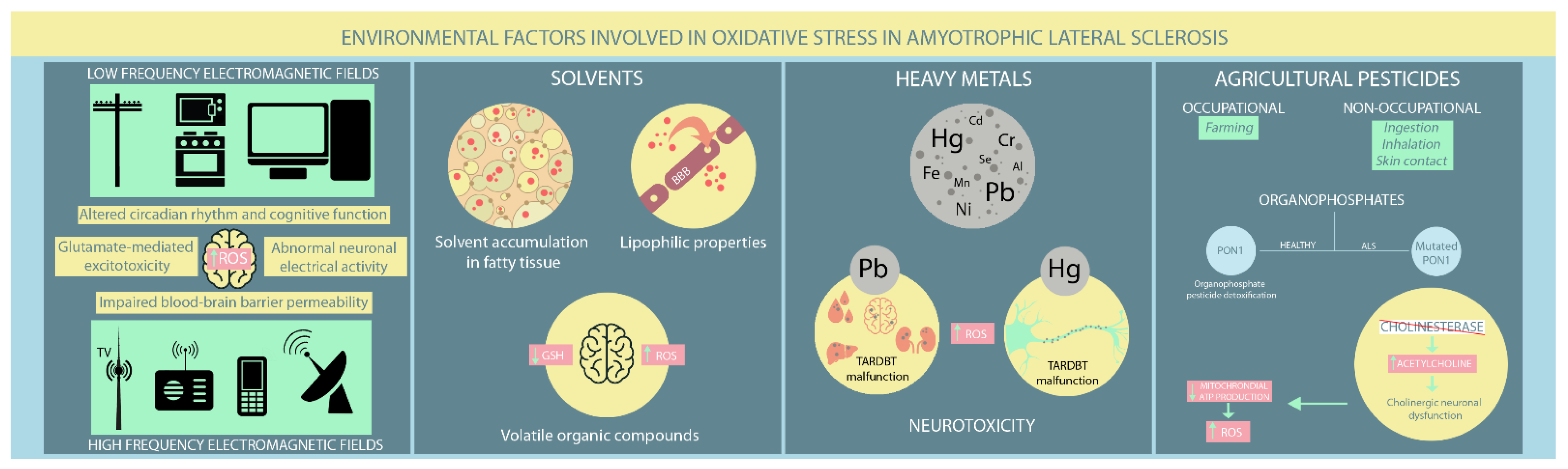

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a grievous neurodegenerative disease whose survival is limited to only a few years. In spite of intensive research to discover the underlying mechanisms, the results are fairly inconclusive. Multiple hypotheses have been regarded, including genetic, molecular, and cellular processes. Notably, oxidative stress has been demonstrated to play a crucial role in ALS pathogenesis. In addition to already recognized and exhaustively studied genetic mutations involved in oxidative stress production, exposure to various environmental factors (e.g., electromagnetic fields, solvents, pesticides, heavy metals) has been suggested to enhance oxidative damage.

- amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- oxidative stress

- genetic factors

- environmental factors

- neurodegeneration

1. Introduction

2. OS and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in ALS

3. Genetic Variants and OS

3.1. SOD1 Mutations

3.2. TARDBP Mutation

3.3. FUS Mutation

4. Environmental Factors Associated with OS in ALS

4.1. EMFs

4.2. Solvents

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms23169339

References

- Smith, E.F.; Shaw, P.J.; De Vos, K.J. The role of mitochondria in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 710, 132933.

- Ingre, C.; Roos, P.M.; Piehl, F.; Kamel, F.; Fang, F. Risk factors for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Epidemiol. 2015, 7, 181–193.

- Greco, V.; Longone, P.; Spalloni, A.; Pieroni, L.; Urbani, A. Crosstalk Between Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Damage: Focus on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1158, 71–82.

- Van Es, M.A.; Hardiman, O.; Chio, A.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Pasterkamp, R.J.; Veldink, J.H.; van den Berg, L.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 2017, 390, 2084–2098.

- Turner, M.R.; Hardiman, O.; Benatar, M.; Brooks, B.R.; Chio, A.; de Carvalho, M.; Ince, P.G.; Lin, C.; Miller, R.G.; Mitsumoto, H.; et al. Controversies and priorities in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 310–322.

- Valko, K.; Ciesla, L. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Prog. Med. Chem. 2019, 58, 63–117.

- Sbodio, J.I.; Snyder, S.H.; Paul, B.D. Redox Mechanisms in Neurodegeneration: From Disease Outcomes to Therapeutic Opportunities. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2019, 30, 1450–1499.

- Cunha-Oliveira, T.; Montezinho, L.; Mendes, C.; Firuzi, O.; Saso, L.; Oliveira, P.J.; Silva, F.S.G. Oxidative Stress in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Pathophysiology and Opportunities for Pharmacological Intervention. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 15, 5021694.

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763.

- Carrì, M.T.; Valle, C.; Bozzo, F.; Cozzolino, M. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage: Importance in non-SOD1 ALS. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2015, 9, 41.

- Kausar, S.; Wang, F.; Cui, H. The Role of Mitochondria in Reactive Oxygen Species Generation and Its Implications for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2018, 7, 274.

- Murphy, M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009, 417, 1–13.

- Brand, M.D. The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp. Gerontol. 2010, 45, 466–472.

- Cui, H.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, H. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. J. Signal. Transduct. 2012, 2012, 646354.

- Niedzielska, E.; Smaga, I.; Gawlik, M.; Moniczewski, A.; Stankowicz, P.; Pera, J.; Filip, M. Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 4094–4125.

- Agar, J.; Durham, H. Relevance of oxidative injury in the pathogenesis of motor neuron diseases. Amyotroph. Lateral. Scler. Other Motor. Neuron. Disord. 2003, 4, 232–242.

- Singh, A.; Kukreti, R.; Saso, L.; Kukreti, S. Oxidative Stress: A Key Modulator in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2019, 24, 1583.

- Vande Velde, C.; McDonald, K.K.; Boukhedimi, Y.; McAlonis-Downes, M.; Lobsiger, C.S.; Bel Hadj, S.; Zandona, A.; Julien, J.P.; Shah, S.B.; Cleveland, D.W. Misfolded SOD1 associated with motor neuron mitochondria alters mitochondrial shape and distribution prior to clinical onset. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22031.

- Kraft, A.D.; Resch, J.M.; Johnson, D.A.; Johnson, J.A. Activation of the Nrf2-ARE pathway in muscle and spinal cord during ALS-like pathology in mice expressing mutant SOD1. Exp. Neurol. 2007, 207, 107–117.

- Babu, G.N.; Kumar, A.; Chandra, R.; Puri, S.K.; Singh, R.L.; Kalita, J.; Misra, U.K. Oxidant-antioxidant imbalance in the erythrocytes of sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients correlates with the progression of disease. Neurochem. Int. 2008, 52, 1284–1289.

- D’Amico, E.; Factor-Litvak, P.; Santella, R.M.; Mitsumoto, H. Clinical perspective on oxidative stress in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 509–527.

- Anderson, C.J.; Bredvik, K.; Burstein, S.R.; Davis, C.; Meadows, S.M.; Dash, J.; Case, L.; Milner, T.A.; Kawamata, H.; Zuberi, A.; et al. ALS/FTD mutant CHCHD10 mice reveal a tissue-specific toxic gain-of-function and mitochondrial stress response. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 138, 103–121.

- Bannwarth, S.; Ait-El-Mkadem, S.; Chaussenot, A.; Genin, E.C.; Lacas-Gervais, S.; Fragaki, K.; Berg-Alonso, L.; Kageyama, Y.; Serre, V.; Moore, D.G.; et al. A mitochondrial origin for frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis through CHCHD10 involvement. Brain 2014, 137 Pt. 8, 2329–2345.

- Genin, E.C.; Plutino, M.; Bannwarth, S.; Villa, E.; Cisneros-Barroso, E.; Roy, M.; Ortega-Vila, B.; Fragaki, K.; Lespinasse, F.; Pinero-Martos, E.; et al. CHCHD10 mutations promote loss of mitochondrial cristae junctions with impaired mitochondrial genome maintenance and inhibition of apoptosis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 58–72.

- Vehviläinen, P.; Koistinaho, J.; Gundars, G. Mechanisms of mutant SOD1 induced mitochondrial toxicity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014, 8, 126.

- Kawamata, H.; Manfredi, G. Different regulation of wild-type and mutant Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase localization in mammalian mitochondria. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, 3303–3317.

- Tafuri, F.; Ronchi, D.; Magri, F.; Comi, G.P.; Corti, S. SOD1 misplacing and mitochondrial dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis pathogenesis. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2015, 9, 336.

- Sasaki, S.; Warita, H.; Murakami, T.; Shibata, N.; Komori, T.; Abe, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Iwata, M. Ultrastructural study of aggregates in the spinal cord of transgenic mice with a G93A mutant SOD1 gene. Acta Neuropathol. 2005, 109, 247–255.

- Higgins, C.M.; Jung, C.; Ding, H.; Xu, Z. Mutant Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase that causes motoneuron degeneration is present in mitochondria in the CNS. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, RC215.

- Hitchler, M.J.; Domann, F.E. Regulation of CuZnSOD and its redox signaling potential: Implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2014, 20, 1590–1598.

- Barber, S.C.; Mead, R.J.; Shaw, P.J. Oxidative stress in ALS: A mechanism of neurodegeneration and a therapeutic target. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1762, 1051–1067.

- Carroll, M.C.; Outten, C.E.; Proescher, J.B.; Rosenfeld, L.; Watson, W.H.; Whitson, L.J.; Hart, P.J.; Jensen, L.T.; Cizewski Culotta, V. The effects of glutaredoxin and copper activation pathways on the disulfide and stability of Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 28648–28656.

- Pasinelli, P.; Belford, M.E.; Lennon, N.; Bacskai, B.J.; Hyman, B.T.; Trotti, D.; Brown, R.H., Jr. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated SOD1 mutant proteins bind and aggregate with Bcl-2 in spinal cord mitochondria. Neuron 2004, 43, 19–30.

- Feneberg, E.; Gordon, D.; Thompson, A.G.; Finelli, M.J.; Dafinca, R.; Candalija, A.; Charles, P.D.; Mäger, I.; Wood, M.J.; Fischer, R.; et al. An ALS-linked mutation in TDP-43 disrupts normal protein interactions in the motor neuron response to oxidative stress. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 144, 105050.

- Afroz, T.; Hock, E.M.; Ernst, P.; Foglieni, C.; Jambeau, M.; Gilhespy, L.A.B.; Laferriere, F.; Maniecka, Z.; Plückthun, A.; Mittl, P.; et al. Functional and dynamic polymerization of the ALS-linked protein TDP-43 antagonizes its pathologic aggregation. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 45.

- Aulas, A.; Vande Velde, C. Alterations in stress granule dynamics driven by TDP-43 and FUS: A link to pathological inclusions in ALS? Front. Cell Neurosci. 2015, 9, 423.

- Blokhuis, A.M.; Koppers, M.; Groen, E.J.N.; van den Heuvel, D.M.A.; Dini Modigliani, S.; Anink, J.J.; Fumoto, K.; van Diggelen, F.; Snelting, A.; Sodaar, P.; et al. Comparative interactomics analysis of different ALS-associated proteins identifies converging molecular pathways. Acta. Neuropathol. 2016, 132, 175–196.

- Buratti, E. Functional Significance of TDP-43 Mutations in Disease. Adv. Genet. 2015, 91, 1–53.

- Prasad, A.; Bharathi, V.; Sivalingam, V.; Girdhar, A.; Patel, B.K. Molecular Mechanisms of TDP-43 Misfolding and Pathology in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 25.

- Park, S.K.; Park, S.; Liebman, S.W. Respiration Enhances TDP-43 Toxicity, but TDP-43 Retains Some Toxicity in the Absence of Respiration. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 2050–2059.

- Gautam, M.; Jara, J.H.; Kocak, N.; Rylaarsdam, L.E.; Kim, K.D.; Bigio, E.H.; Hande Özdinler, P. Mitochondria, ER, and nuclear membrane defects reveal early mechanisms for upper motor neuron vulnerability with respect to TDP-43 pathology. Acta. Neuropathol. 2019, 137, 47–69.

- Cohen, T.J.; Hwang, A.W.; Unger, T.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M. Redox signalling directly regulates TDP-43 via cysteine oxidation and disulphide cross-linking. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 1241–1252.

- Cohen, T.J.; Hwang, A.W.; Restrepo, C.R.; Yuan, C.X.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M. An acetylation switch controls TDP-43 function and aggregation propensity. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5845.

- Magrané, J.; Cortez, C.; Gan, W.B.; Manfredi, G. Abnormal mitochondrial transport and morphology are common pathological denominators in SOD1 and TDP43 ALS mouse models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 1413–1424.

- Wang, W.; Li, L.; Lin, W.L.; Dickson, D.W.; Petrucelli, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. The ALS disease-associated mutant TDP-43 impairs mitochondrial dynamics and function in motor neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 4706–4719.

- Duan, W.; Li, X.; Shi, J.; Guo, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, C. Mutant TAR DNA-binding protein-43 induces oxidative injury in motor neuron-like cell. Neuroscience 2010, 169, 1621–1629.

- Tian, Y.P.; Che, F.Y.; Su, Q.P.; Lu, Y.C.; You, C.P.; Huang, L.M.; Wang, S.G.; Wang, L.; Yu, J.X. Effects of mutant TDP-43 on the Nrf2/ARE pathway and protein expression of MafK and JDP2 in NSC-34 cells. Genet. Mol. Res. 2017, 16, gmr16029638.

- Shang, Y.; Huang, E.J. Mechanisms of FUS mutations in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Res. 2016, 1647, 65–78.

- Lattante, S.; Rouleau, G.A.; Kabashi, E. TARDBP and FUS mutations associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Summary and update. Hum. Mutat. 2013, 34, 812–826.

- Wang, H.; Guo, W.; Mitra, J.; Hegde, P.M.; Vandoorne, T.; Eckelmann, B.J.; Mitra, S.; Tomkinson, A.E.; Van Den Bosch, L.; Hegde, M.L. Mutant FUS causes DNA ligation defects to inhibit oxidative damage repair in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3683.

- Luna, J.; Leleu, J.P.; Preux, P.M.; Corcia, P.; Couratier, P.; Marin, B.; Boumediene, F.; Fralim Consortium. Residential exposure to ultra high frequency electromagnetic fields emitted by Global System for Mobile (GSM) antennas and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis incidence: A geo-epidemiological population-based study. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108525.

- Gunnarsson, L.G.; Bodin, L. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Occupational Exposures: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2018, 15, 2371.

- Gunnarsson, L.G.; Bodin, L. Occupational Exposures and Neurodegenerative Diseases-A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2019, 16, 337.

- Koeman, T.; Slottje, P.; Schouten, L.J.; Peters, S.; Huss, A.; Veldink, J.H.; Kromhout, H.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Vermeulen, R. Occupational exposure and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a prospective cohort. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 578–585.

- Filippini, T.; Tesauro, M.; Fiore, M.; Malagoli, C.; Consonni, M.; Violi, F.; Iacuzio, L.; Arcolin, E.; Oliveri Conti, G.; Cristaldi, A.; et al. Environmental and Occupational Risk Factors of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2020, 17, 2882.

- Seelen, M.; Vermeulen, R.C.; van Dillen, L.S.; van der Kooi, A.J.; Huss, A.; de Visser, M.; van den Berg, L.H.; Veldink, J.H. Residential exposure to extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields and the risk of ALS. Neurology 2014, 83, 1767–1769.

- Riancho, J.; Sanchez de la Torre, J.R.; Paz-Fajardo, L.; Limia, C.; Santurtun, A.; Cifra, M.; Kourtidis, K.; Fdez-Arroyabe, P. The role of magnetic fields in neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2021, 65, 107–117.

- Capozzella, A.; Sacco, C.; Chighine, A.; Loreti, B.; Scala, B.; Casale, T.; Sinibaldi, F.; Tomei, G.; Giubilati, R.; Tomei, F.; et al. Work related etiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): A meta-analysis. Ann. Ig. 2014, 26, 456–472.

- Consales, C.; Merla, C.; Marino, C.; Benassi, B. Electromagnetic fields, oxidative stress, and neurodegeneration. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 2012, 683897.

- Poulletier de Gannes, F.; Ruffié, G.; Taxile, M.; Ladevèze, E.; Hurtier, A.; Haro, E.; Duleu, S.; Charlet de Sauvage, R.; Billaudel, B.; Geffard, M.; et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and extremely-low frequency (ELF) magnetic fields: A study in the SOD-1 transgenic mouse model. Amyotroph. Lateral. Scler. 2009, 10, 370–373.

- Filippini, T.; Hatch, E.E.; Vinceti, M. Residential exposure to electromagnetic fields and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A dose-response meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11939.

- Falone, S.; Mirabilio, A.; Carbone, M.C.; Zimmitti, V.; Di Loreto, S.; Mariggiò, M.A.; Mancinelli, R.; Di Ilio, C.; Amicarelli, F. Chronic exposure to 50 Hz magnetic fields causes a significant weakening of antioxidant defence systems in aged rat brain. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 2762–2770.

- Jelenković, A.; Janać, B.; Pesić, V.; Jovanović, D.M.; Vasiljević, I.; Prolić, Z. Effects of extremely low-frequency magnetic field in the brain of rats. Brain. Res. Bull. 2006, 68, 355–360.

- Oshiro, S.; Morioka, M.S.; Kikuchi, M. Dysregulation of iron metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 2011, 378278.

- Liebl, M.P.; Windschmitt, J.; Besemer, A.S.; Schäfer, A.K.; Reber, H.; Behl, C.; Clement, A.M. Low-frequency magnetic fields do not aggravate disease in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8585.

- Ratner, M.H.; Jabre, J.F.; Ewing, W.M.; Abou-Donia, M.; Oliver, L.C. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—A case report and mechanistic review of the association with toluene and other volatile organic compounds. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2018, 61, 251–260.

- Dickerson, A.S.; Hansen, J.; Thompson, S.; Gredal, O.; Weisskopf, M.G. A mixtures approach to solvent exposures and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A population-based study in Denmark. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 241–249.

- Peters, T.L.; Kamel, F.; Lundholm, C.; Feychting, M.; Weibull, C.E.; Sandler, D.P.; Wiebert, P.; Sparén, P.; Ye, W.; Fang, F. Occupational exposures and the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 87–92.

- Fang, F.; Quinlan, P.; Ye, W.; Barber, M.K.; Umbach, D.M.; Sandler, D.P.; Kamel, F. Workplace exposures and the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Environ. Health. Perspect. 2009, 117, 1387–1392.

- Roberts, A.L.; Johnson, N.J.; Cudkowicz, M.E.; Eum, K.D.; Weisskopf, M.G. Job-related formaldehyde exposure and ALS mortality in the USA. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2016, 87, 786–788.

- Weisskopf, M.G.; Morozova, N.; O’Reilly, E.J.; McCullough, M.L.; Calle, E.E.; Thun, M.J.; Ascherio, A. Prospective study of chemical exposures and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2009, 80, 558–561.

- Malek, A.M.; Barchowsky, A.; Bowser, R.; Youk, A.; Talbott, E.O. Pesticide exposure as a risk factor for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A meta-analysis of epidemiological studies: Pesticide exposure as a risk factor for ALS. Environ. Res. 2012, 117, 112–119.

- Andrew, A.S.; Caller, T.A.; Tandan, R.; Duell, E.J.; Henegan, P.L.; Field, N.C.; Bradley, W.G.; Stommel, E.W. Environmental and Occupational Exposures and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in New England. Neurodegener. Dis. 2017, 17, 110–116.

- Malek, A.M.; Barchowsky, A.; Bowser, R.; Heiman-Patterson, T.; Lacomis, D.; Rana, S.; Youk, A.; Talbott, E.O. Exposure to hazardous air pollutants and the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 197, 181–186.

- Georgieva, T.; Michailova, A.; Panev, T.; Popov, T. Possibilities to control the health risk of petrochemical workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2002, 75, S21–S26.

- Cheong, I.; Marjańska, M.; Deelchand, D.K.; Eberly, L.E.; Walk, D.; Öz, G. Ultra-High Field Proton MR Spectroscopy in Early-Stage Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 42, 1833–1844, Erratum in 2017, 42, 1845–1846.

- Foerster, B.R.; Pomper, M.G.; Callaghan, B.C.; Petrou, M.; Edden, R.A.; Mohamed, M.A.; Welsh, R.C.; Carlos, R.C.; Barker, P.B.; Feldman, E.L. An imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis revealed by use of 3-T proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. JAMA. Neurol. 2013, 70, 1009–1016.

- Weiduschat, N.; Mao, X.; Hupf, J.; Armstrong, N.; Kang, G.; Lange, D.J.; Mitsumoto, H.; Shungu, D.C. Motor cortex glutathione deficit in ALS measured in vivo with the J-editing technique. Neurosci. Lett. 2014, 570, 102–107.

- Myhre, O.; Fonnum, F. The effect of aliphatic, naphthenic, and aromatic hydrocarbons on production of reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species in rat brain synaptosome fraction: The involvement of calcium, nitric oxide synthase, mitochondria, and phospholipase A. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001, 62, 119–128.

- Mills, K.R.; Nithi, K.A. Corticomotor threshold is reduced in early sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 1997, 20, 1137–1141.

- Kikuchi, H.; Doh-ura, K.; Kawashima, T.; Kira, J.; Iwaki, T. Immunohistochemical analysis of spinal cord lesions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) antibodies. Acta Neuropathol. 1999, 97, 13–21.

- Farah, C.A.; Nguyen, M.D.; Julien, J.P.; Leclerc, N. Altered levels and distribution of microtubule-associated proteins before disease onset in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurochem. 2003, 84, 77–86.

- Gotohda, T.; Tokunaga, I.; Kitamura, O.; Kubo, S. Toluene inhalation induced neuronal damage in the spinal cord and changes of neurotrophic factors in rat. Leg. Med. 2007, 9, 123–127.