| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | lingyun Wang | -- | 1440 | 2022-08-26 04:33:32 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | + 10 word(s) | 1450 | 2022-08-29 03:44:53 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1450 | 2022-08-29 04:42:10 | | | | |

| 4 | Conner Chen | + 4 word(s) | 1454 | 2022-08-29 10:36:28 | | | | |

| 5 | Conner Chen | + 3 word(s) | 1457 | 2022-09-01 13:13:55 | | |

Video Upload Options

Several tumor polyamine-suppressing strategies have been developed, as follows. (1) Ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) and S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase 1 (AMD1) are important for polyamine synthesis. The α-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO), which acts as an irreversible suicide inhibitor of ODC, has been used to prevent and treat multiple cancers, such as pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer, lung carcinoma, neuroblastoma, endometrial cancer, and osteosarcoma. (2) Highly regulated catabolic pathways are utilized to control the intracellular polyamine pool. The modulation of the polyamine catabolic enzyme produces decreasing polyamine content and induces the generation of toxic compounds. (3) Some inhibitors targeting the polyamine transport system (PTS) can hinder polyamine import and antagonize polyamine uptake. (4) Synthetic polyamines, including polyamine analogs and polyamine conjugates, possess anticancer activity against tumor cells.

1. Small Molecules Target Polyamine Metabolism

1.1. Polyamine Analogs

1.2. Polyamine Conjugates

2. Combinations Target Multiple Components

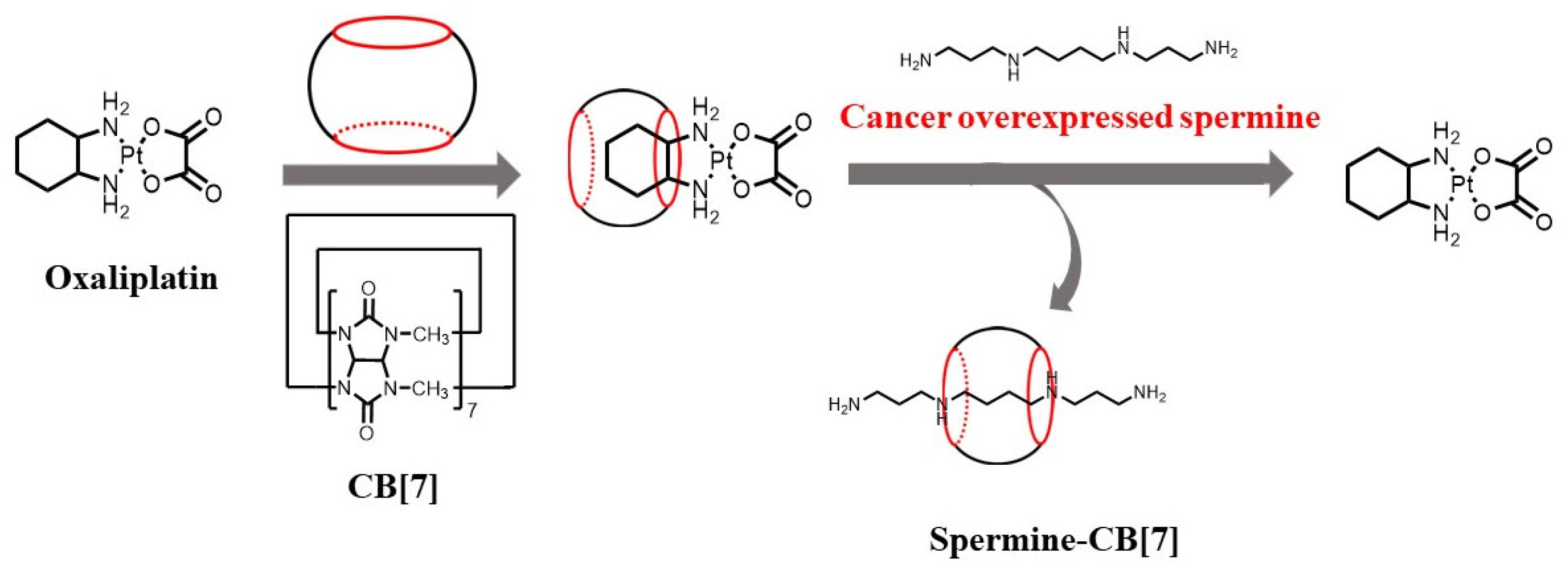

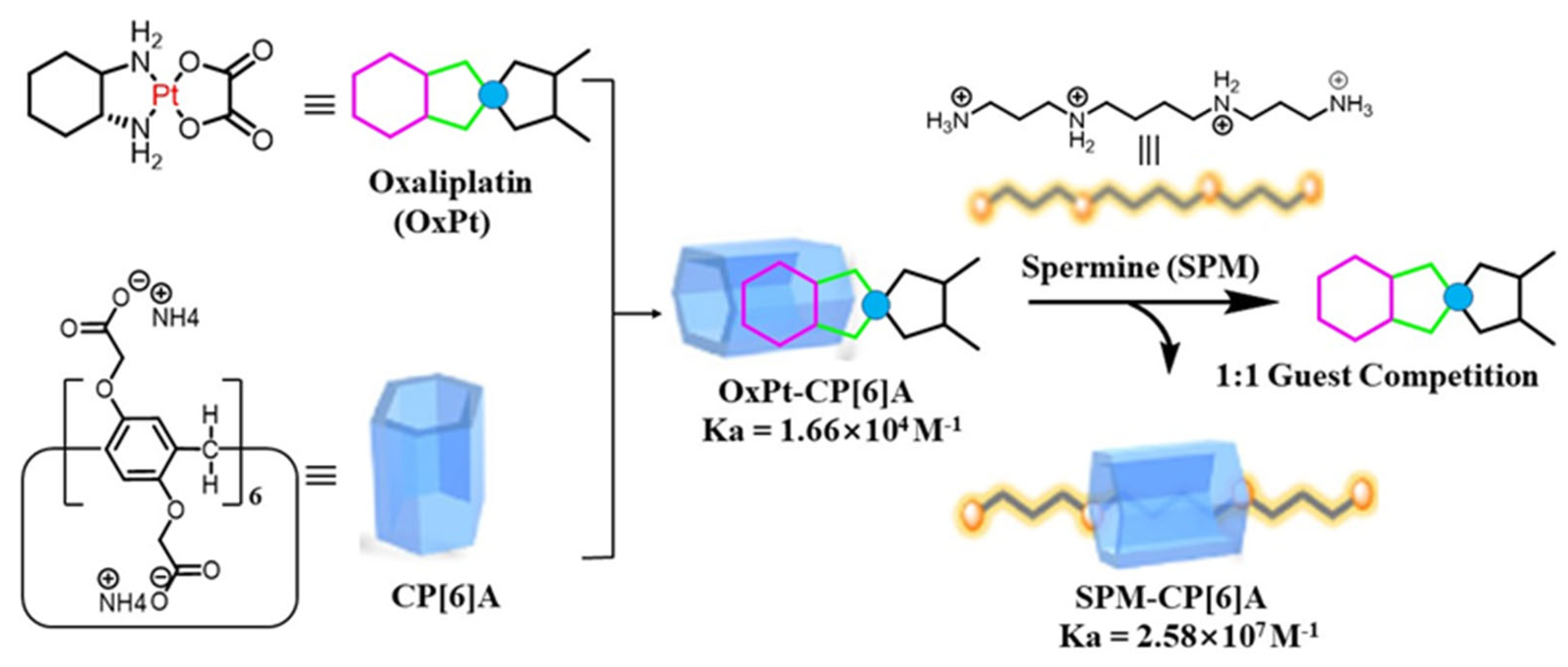

2.1. Spermine-Responsive Supramolecular Chemotherapy

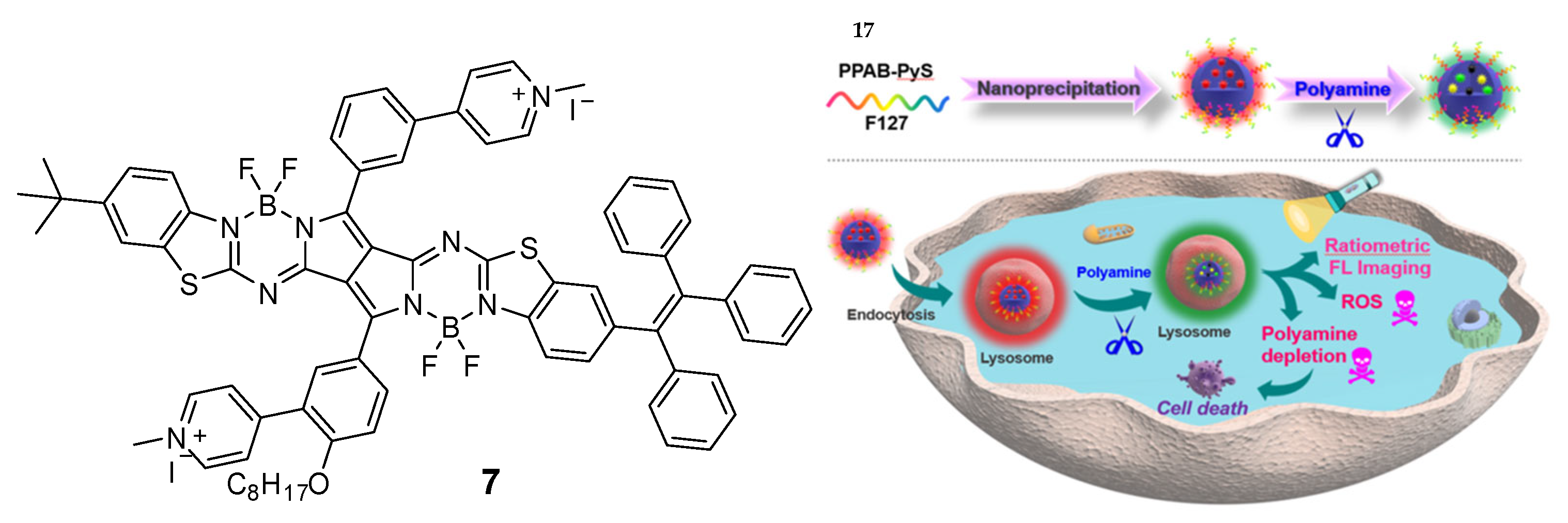

2.2. Combination of Polyamine Consumption and Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

References

- Ploskonos, M.V.; Syatkin, S.P.; Neborak, E.V.; Hilal, A.; Sungrapova, K.Y.; Sokuyev, R.I.; Blagonravov, M.L.; Korshunova, A.Y.; Terentyev, A.A. Polyamine Analogues of Propanediamine Series Inhibit Prostate Tumor Cell Growth and Activate the Polyamine Catabolic Pathway. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 1437–1441.

- Thomas, T.J.; Thomas, T. Cellular and Animal Model Studies on the Growth Inhibitory Effects of Polyamine Analogues on Breast Cancer. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 24.

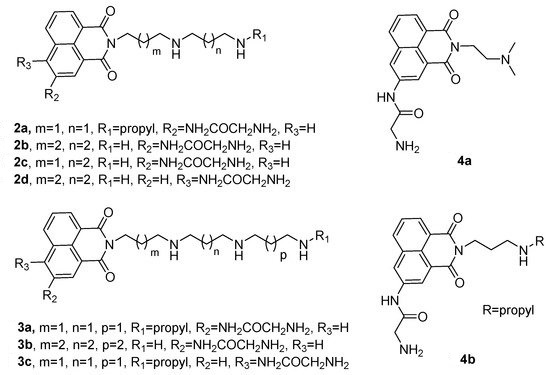

- Ma, J.; Li, L.; Yue, K.; Zhang, Z.; Su, S.; Chen, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhang, P.; Ma, R.; Li, Y.; et al. A Naphthalimide-Polyamine Conjugate Preferentially Accumulates in Hepatic Carcinoma Metastases as a Lysosome-Targeted Antimetastatic Agent. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 221, 113469.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Li, M.; Xie, S.; Wang, C. Synthesis and Evaluation of Novel Amonafide-Polyamine Conjugates as Anticancer Agents. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2017, 89, 670–680.

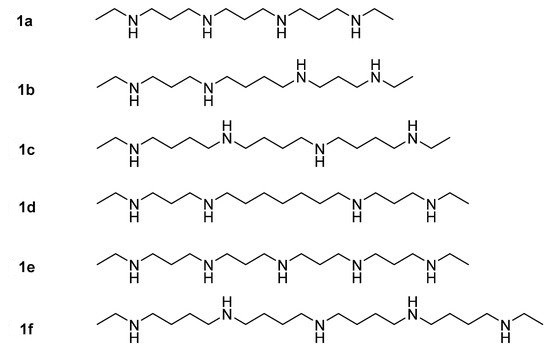

- Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Ge, C.; Chang, L.; Wang, C.; Tian, Z.; Wang, S.; Dai, F.; Zhao, L.; Xie, S. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Alkylated Polyamine Analogues as Potential Anticancer Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 1732–1743.

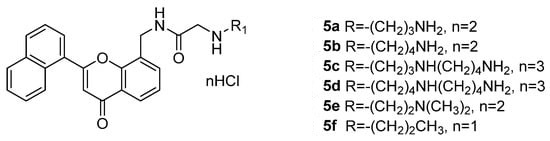

- Li, Q.; Zhai, Y.; Luo, W.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xie, S.; Hong, C.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhao, J.; et al. Synthesis and Biological Properties of Polyamine Modified Flavonoids as Hepatocellular Carcinoma Inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 121, 110–119.

- Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Chang, Y.; Ge, C.; Li, X.; Feng, Y.; Xie, S.; Wang, C.; Dai, F.; Luo, W. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Asymmetric Naphthalene Diimide Derivatives as Anticancer Agents Depending on Ros Generation. MedChemComm 2018, 9, 1377–1385.

- Li, Q.; Zhu, Z.X.; Zhang, X.; Luo, W.; Chang, L.P.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.X.; Xie, S.Q.; Chang, C.C.; Wang, C.J. The Lead Optimization of the Polyamine Conjugate of Flavonoid with a Naphthalene Motif: Synthesis and Biological Evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 146, 564–576.

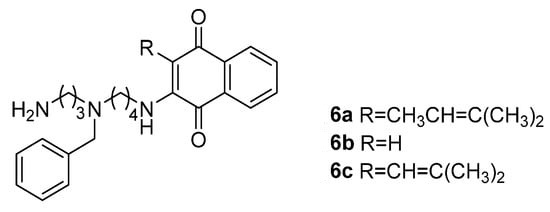

- Manickam, M.; Boggu, P.R.; Pillaiyar, T.; Nam, Y.J.; Abdullah, M.; Lee, S.J.; Kang, J.S.; Jung, S.H. Design, Synthesis and Anticancer Activity of 2-Amidomethoxy-1,4-Naphthoquinones and Its Conjugates with Biotin/Polyamine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 31, 127685.

- Romao, L.; do Canto, V.P.; Netz, P.A.; Pinto, A.C.; Follmer, C. Conjugation with Polyamines Enhances the Antitumor Activity of Naphthoquinones against Human Glioblastoma Cells. Anticancer Drugs 2018, 29, 520–529.

- Fidanzi-Dugas, C.; Liagre, B.; Chemin, G.; Perraud, A.; Carrion, C.; Couquet, C.Y.; Granet, R.; Sol, V.; Leger, D.Y. Analysis of the in Vitro and in Vivo Effects of Photodynamic Therapy on Prostate Cancer by Using New Photosensitizers, Protoporphyrin Ix-Polyamine Derivatives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 1676–1690.

- Xie, X.W.; Liu, Z.P.; Li, X. Design, Synthesis, Bioevaluation of Lfc- and Pa-Tethered Anthraquinone Analogues of Mitoxantrone. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 101, 104005.

- Rioux, B.; Pinon, A.; Gamond, A.; Martin, F.; Laurent, A.; Champavier, Y.; Barette, C.; Liagre, B.; Fagnere, C.; Sol, V.; et al. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Chalcone-Polyamine Conjugates as Novel Vectorized Agents in Colorectal and Prostate Cancer Chemotherapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 222, 113586.

- Chen, Y.; Huang, Z.; Xu, J.F.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, X. Cytotoxicity Regulated by Host-Guest Interactions: A Supramolecular Strategy to Realize Controlled Disguise and Exposure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 22780–22784.

- Chen, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Xu, J.I.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, X. Supramolecular Chemotherapy: Cooperative Enhancement of Antitumor Activity by Combining Controlled Release of Oxaliplatin and Consuming of Spermine by CucurbitUril. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 8602–8608.

- Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Wu, H.; Xu, J.F.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, X. Supramolecular Polymeric Chemotherapy Based on CucurbitUril-Peg. Copolymer. Biomater. 2018, 178, 697–705.

- Ding, Y.F.; Wei, J.; Li, S.; Pan, Y.T.; Wang, R. Host–Guest Interactions Initiated Supramolecular Chitosan Nanogels for Selective Intracellular Drug Delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 28665–28670.

- Chen, Y.; Jing, L.; Meng, Q.; Li, B.; Chen, R.; Sun, Z. Supramolecular Chemotherapy: Noncovalent Bond Synergy of Cu-curbituril against Human Colorectal Tumor Cells. Langmuir 2021, 37, 9547–9552.

- Huang, X.; Zhou, H.; Jiao, R.; Liu, H.; Qin, C.; Xu, L.; Chen, Y. Supramolecular Chemotherapy: Host−Guest Complexes of Heptaplatin-cucurbituril toward Colorectal Normal and Tumor Cells. Langmuir 2021, 37, 5475–5482.

- Hao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Z.; Xu, J.F.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, X. Supramolecular Chemotherapy: Carboxylated PillarArene for Decreasing Cytotoxicity of Oxaliplatin to Normal Cells and Improving Its Anticancer Bioactivity against Colorectal Cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 5365–5372.

- Cheng, Q.; Teng, K.; Ding, Y.; Yue, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, R. Dual Stimuli-Responsive BispillarArene-Based Nanoparticles for Precisely Selective Drug Delivery in Cancer Cells. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2340–2343.

- Sun, C.; Wang, Z.; Yang, K.; Yue, L.; Cheng, Q.; Ma, Y.; Lu, S.; Chen, G.; Wang, R. Polyamine-Responsive Morphological Transformation of a Supramolecular Peptide for Specific Drug Accumulation and Retention in Cancer Cells. Small 2021, 17, 2101139.

- Chen, J.; Ni, H.; Meng, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, C. Supramolecular Trap for Catching Polyamines in Cells as an Anti-Tumor Strategy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3546.

- Li, W.; Wang, L.; Sun, T.; Tang, H.; Bui, B.; Cao, D.; Wang, R.; Chen, W. Characterization of Nanoparticles Combining Polyamine Detection with Photodynamic Therapy. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 803.