| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EKATI DRAKOPOULOU | -- | 5229 | 2022-08-19 11:46:38 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | -60 word(s) | 5169 | 2022-08-22 05:52:45 | | |

Video Upload Options

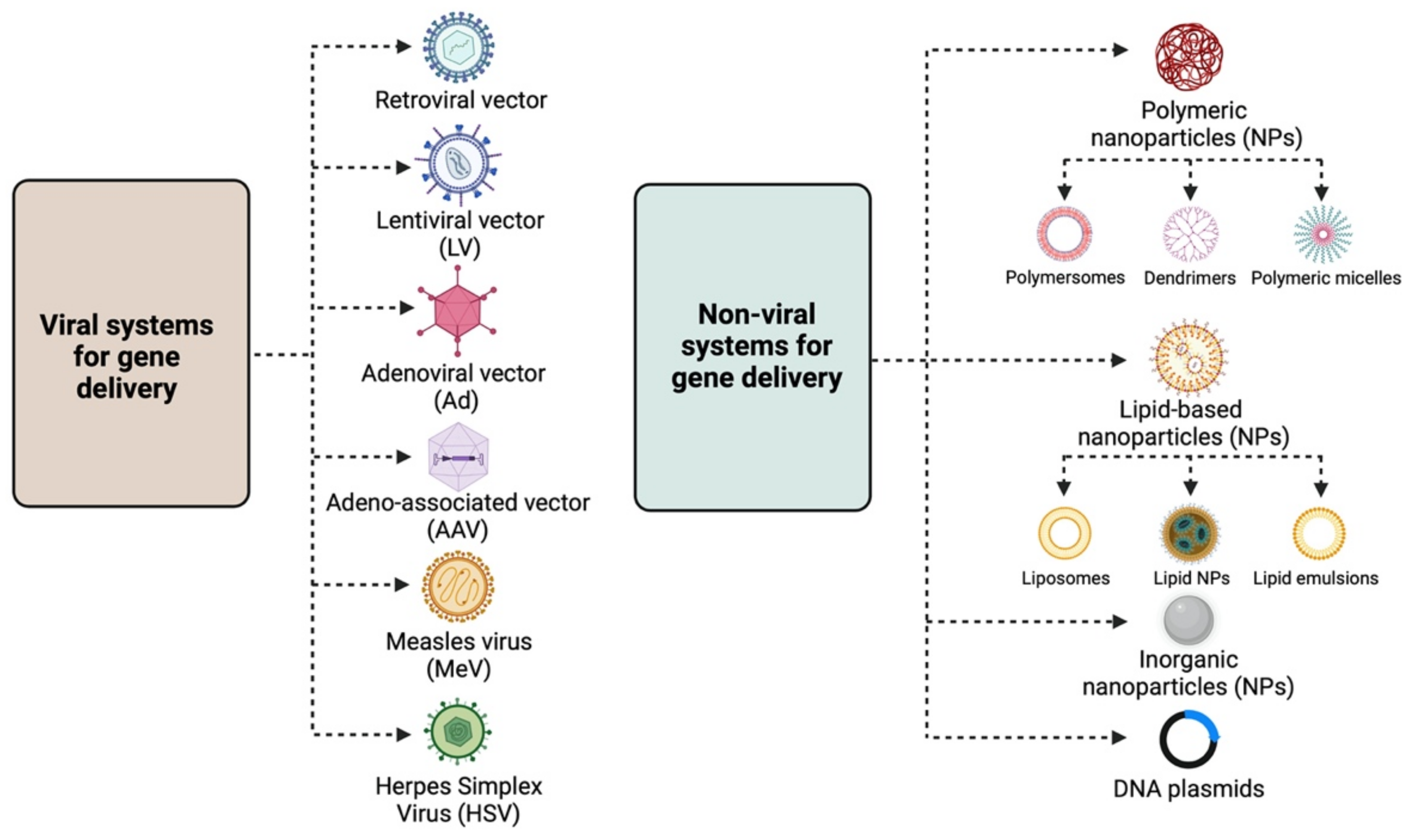

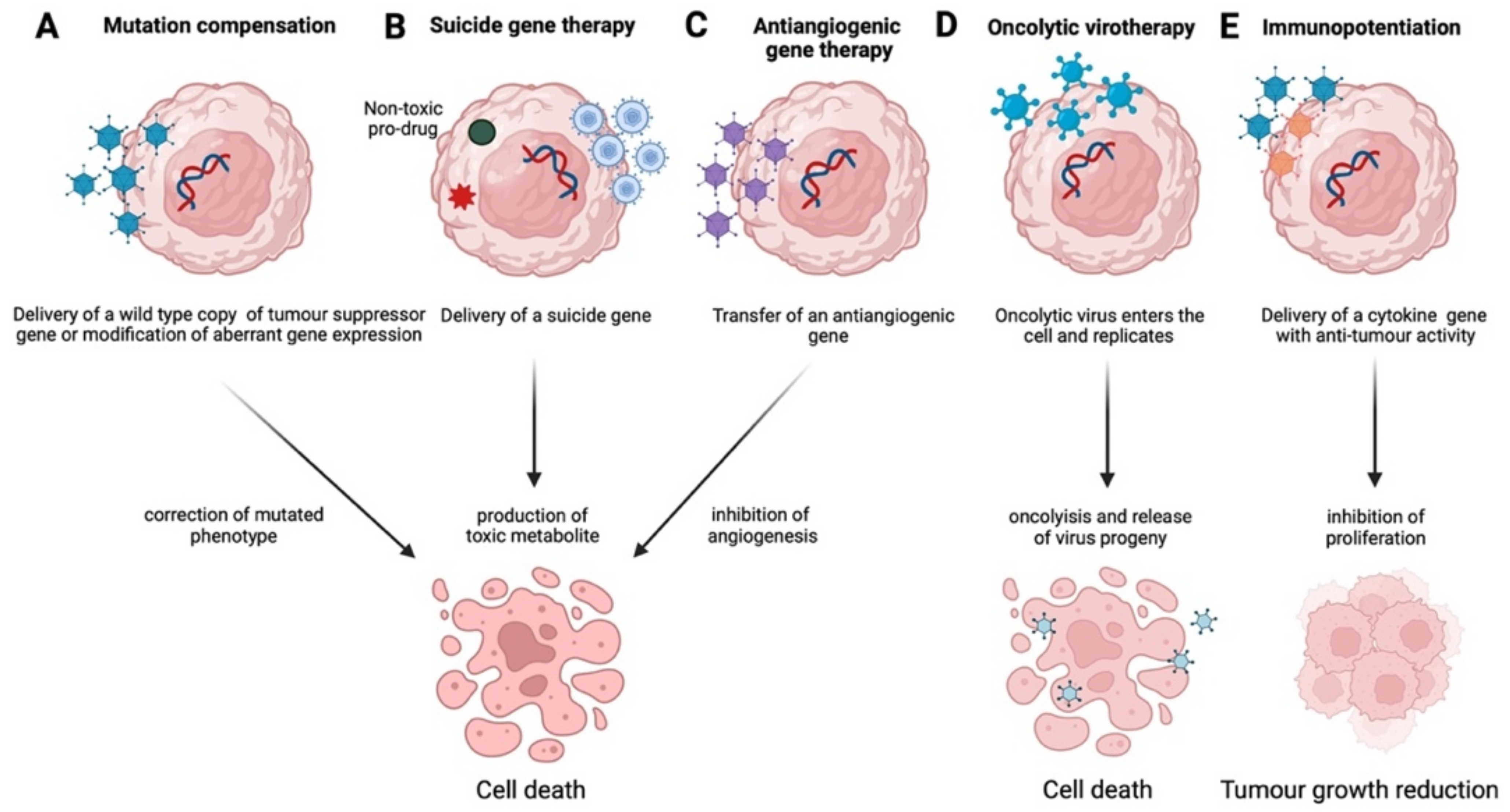

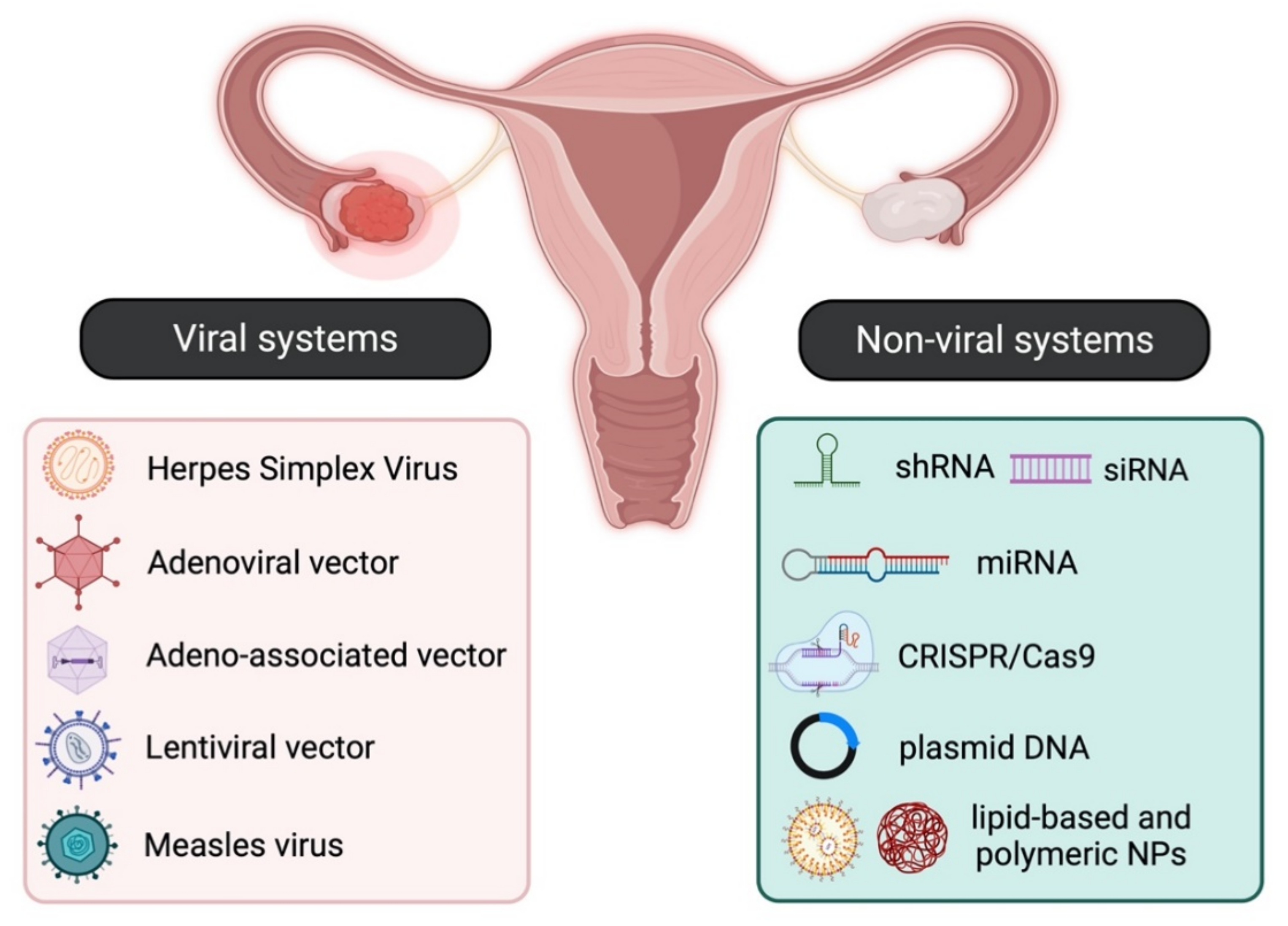

Gene therapy aims to introduce or modify genetic material into target cells, thus altering their function, usually by either restoring a lost function or initiating a new one. Although it was initially employed for the treatment of inherited genetic diseases, gene therapy was soon identified as an effective approach for the treatment of both gynaecological malignancies such as ovarian, cervical, and endometrial cancer and certain benign gynaecological abnormalities, such as leiomyomas, endometriosis, placental, and embryo implantation disorders. There are two main strategies for specific and efficient gene delivery to cancer and non-cancer cells, and these involve either viral or non-viral systems.

1. Gene Delivery Systems

The main strategies for targeted gene therapy approaches for malignant and benign gynaecological disorders employ both viral and non-viral systems (Figure 1).

1.1. Viral Systems

-

Retroviral vectors: Lentiviral vectors (LVs) are the most widely used retroviruses for therapeutic gene delivery, as they can efficiently transduce both quiescent and dividing cells and thus facilitate safe, efficient, and stable transgene expression [3][4]. They are enveloped, single-stranded RNA viruses with a packaging capacity of ~9 kb [3] and have already been employed in numerous successful clinical trials for the treatment of various diseases, such as hemoglobinopathies, metabolic and immune disorders, and various cancer types, including gynaecological malignancies [5]. Moreover, they have been instrumental in the development of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, an approach with promising therapeutic perspectives in the field of oncology;

-

Adenoviral vectors (Ads): Adenoviral vectors have been extensively used as viral vector platforms primarily due to their broad tropism and the high transduction efficiency of both quiescent and dividing cells, as well as for their capacity to persist as episomal elements within the target cells [5]. They mainly derive from human serotypes-2 (Ad2) and -5 (Ad5) adenoviruses, which are non-enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses with an icosahedral capsid able to accommodate up to 45 kb linear, double-stranded DNA [6]. However, since they are usually associated with potent immune responses [7] due to pre-existing immunity, extensive research has focused on generating less immunogenic Ad vectors, employing serotypes with low seroprevalence, such as Ad26 and Ad35 [8]. Furthermore, the generation of conditionally replicative adenoviral vectors (CRAds) by introducing tumour-specific promoters into the Ad genome can lead to higher gene expression [9]. Regarding gene therapy for malignant and benign gynaecological disorders, Ads have been extensively used as therapeutic vectors in both pre-clinical and clinical studies [5] for the delivery of vaccines, tumour suppressor genes, suicide genes, and immunomodulatory genes.

-

Adeno-associated vectors (AAVs): Adeno-associated vectors are single-stranded DNA viruses with an icosahedral capsid of ~5 kb packaging capacity that depend on adenoviruses to complete their life cycle. The current AAV1 and AAV2 serotypes used are characterised by broad tropism, stable episomal persistence, and reduced immunogenicity, and therefore, they have been widely employed in gene therapy approaches [5].

-

Measles virus (MeV): The vaccine strain of MeV is a negative-strand RNA virus with a 16 kb-long genome that presents an attractive oncolytic platform, mainly due to its ability to selectively infect malignant cells, which overexpress the CD46 receptor [10]. Due to the fact that the monotherapy oncolytic approach using MeV is usually not sufficient to treat advanced-stage malignancies, combination approaches using radiotherapy or chemotherapy, MeV harbouring with therapeutic or immunomodulatory genes, and the use of carrier cells for MeV delivery into tumour cells can lead to successful therapeutic outcomes for a number of malignancies, including gynaecological cancers [11];

-

Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV): HSV-1 and HSV-2 members are enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses with an icosahedral capsid, which demonstrate attractive vector features, such as a large accommodation capacity, easy production, and high titers [12]. Apart from their ability to mediate oncolysis upon delivery of the suicide thymidine kinase (TK) suicide gene into malignant cells, HSV vectors have also been used to deliver immunomodulatory cytokines into tumour cells and thus elicit a strong anti-tumour immune response. Extensive research has focused on the development of safer HSV vectors, carrying transcriptionally active promoter elements that overcome the latency of the viral genome, aiming to expand HSV pre-clinical and clinical applications [12].

1.2. Non-Viral Systems

The need for non-viral gene delivery systems arose primarily due to the immunogenicity and cytotoxicity concerns raised by some viral vectors, such as Adenoviruses [7]. Despite the relatively low transfection efficiency, their use in the field of gene therapy has gained a lot of ground [9][13]. The main non-viral approaches involve the delivery of the desired gene material, e.g., naked or plasmid DNA, either by physical methods, such as electroporation, ballistic DNA, injection, photoporation, magnetofection, sonoporation, and hydroporation [9][14], or chemically, by means of polymeric, lipid-based and inorganic nanoparticles (NPs) [9][15].

1.2.1. Physical Methods

-

Electroporation: The electric pulse creates pores in the cell membrane, allowing the genetic material to enter the target cell. Depending on the target tissue, the electric pulse differs both in strength (high or low) and duration (short or long pulses), with cancer cells usually requiring low field strength (<700 V/cm) with long pulses (milliseconds) [9];

-

Ballistic DNA: Bombardment of DNA-coated heavy metal particles into target cells at a certain speed. The precision in DNA delivery makes it a method of choice for ovarian cancer [16];

-

Injection: The genetic material is directly injected into tissue by means of a needle. It represents the preferred approach for solid tumours; however, it has a relatively low efficiency [16];

-

Photoporation: A laser pulse causes cells to be permeable to DNA, with transfection efficiency being dependent on the focal point and laser frequency [9];

-

Magnetofection: It is mostly used for in vitro approaches; a gene-magnetic particle complex is introduced in cell culture, and electromagnets placed below the cell culture generate magnetic fields that mediate its effective sedimentation, thus leading to higher transfection efficiency [9];

-

Sonoporation: The generated ultrasound waves cause cell membranes to be permeable to micro-bubbles containing gene products [9];

-

Hydroporation: Hydrodynamic pressure generated by the injection of a large volume of DNA in a short period of time increases cell membrane permeability and mediates gene delivery [9].

1.2.2. Chemical Vectors

-

Polymeric NPs: These are stable, biodegradable, and water-soluble NPs, which make ideal candidates for drug delivery. They exist as monomers or polymers of different structures, with the most common being nanocapsules and nanospheres. According to shape, they are further divided into polymersomes, dendrimers, and micelles. Polymersomes are artificial vesicles with amphiphilic membranes that display increased cargo capacity and effective cytosol delivery [17], whereas micelles are quite effective for aqueous drug administration due to their hydrophilic core and hydrophobic coating. Polymeric micelles have already been employed in clinical trials, specifically in a study testing the effective delivery of paclitaxel (PTX), a drug widely used for ovarian cancer treatment [18]. Dendrimers are more complex, three-dimensional nanocarriers, commonly used for the delivery of nucleic acids and drugs in cancer therapy, usually in combination with poly amidoamine (PAMAM) and polyethylenimine (PEI) polymers [19]. Despite the toxicity associated with the surface amino groups, PAMAM was the first dendrimer used for gene delivery [13];

-

Lipid-based NPs: They are usually spherical vehicles with an internal aqueous compartment and an external lipid bilayer. They are divided into liposomes or lipoplexes, lipid emulsions (or nanogels), and lipid NPs [13]. Due to their positive charge, cationic liposomes bind to the anionic phosphate group of nucleic acids, forming lipoplexes and interacting with cell membranes, and thus, efficiently deliver nucleic acids into the cell [13]. Lipid emulsions, which are composed of oil, water, and a surface-active agent, show increased stability and serum resistance, whereas solid lipid NPs can protect nucleic acids from nucleases and are primarily employed for siRNA delivery [16];

-

Inorganic NPs: These nanoparticles are composed of inorganic materials, such as iron, gold, and silica, and therefore possess unique electrical, magnetic, and optical properties [9][15]. The most widely used inorganic NPs are gold NPs, primarily due to their low toxicity, while their photothermal properties establish them as good candidates for cancer therapy [20].

2. Gene Therapy for Gynaecological Cancers

2.1. Ovarian Cancer

2.1.1. Viral Vectors

Retroviruses

Adenoviruses (Ads) and Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs)

Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV), Measles Virus (MeV), and Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV)

2.1.2. Non-Viral Systems

Plasmids

Nanoparticles (NPs)

miRNAs

2.2. Cervical Cancer

2.2.1. Viral Vectors

Lentiviruses

Adenoviruses (Ad) and Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAV)

2.2.2. Non-Viral Systems

Nanoparticles (NPs)

Plasmids

miRNAs

2.3. Endometrial Cancer

2.3.1. Viral Vectors

2.3.2. Non-Viral Systems

3. Gene Therapy for Benign Gynaecological Disorders

3.1. Uterine Leiomyomas or Fibroids

3.2. Endometriosis

3.3. Placental Disorders

3.4. Embryo Implantation Disorders

4. Conclusions

It is clear that targeted gene therapy approaches, such as mutation compensation, antiangiogenesis, immunopotentiation, suicide gene therapy, and oncolytic virotherapy, have yielded promising results, employing both viral and non-viral systems. However, most of these strategies either remain in the preclinical phase or show reduced effectiveness as monotherapies and usually require a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy to demonstrate a therapeutic outcome. Furthermore, gene therapy in combination with immunotherapy, e.g., targeting CTLA-4 and PD-1, or with the emerging therapeutic angiogenesis inhibitors, may result in increased effectiveness, especially for ovarian cancer in advanced stages, where still no effective therapies exist. Moreover, there is increasing evidence for the therapeutic potential of CAR T-cell technology also, and clinical trials are currently assessing its efficacy, primarily in ovarian cancer, by recruiting patients [47]. The continuous development of safe and effective vectors, the discovery of novel diagnostic markers, such as miRNAs discussed above, or of new players, such as long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [99] and circular RNAs (circRNAs) [100] and in combination with more clinical trials beyond Phase I/II are expected to lead to more effective and radical therapeutic outcomes.

References

- Hassan, M.H.; Othman, E.E.; Hornung, D.; Al-Hendy, A. Gene therapy of benign gynecological diseases. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 822–835.

- Brooks, R.A.; Mutch, D.G. Gene therapy in gynecological cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2006, 6, 1013–1032.

- Naldini, L.; Blomer, U.; Gallay, P.; Ory, D.; Mulligan, R.; Gage, F.H.; Verma, I.M.; Trono, D. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science 1996, 272, 263–267.

- Naldini, L.; Blomer, U.; Gage, F.H.; Trono, D.; Verma, I.M. Efficient transfer, integration, and sustained long-term expression of the transgene in adult rat brains injected with a lentiviral vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 11382–11388.

- Bulcha, J.T.; Wang, Y.; Ma, H.; Tai, P.W.L.; Gao, G. Viral vector platforms within the gene therapy landscape. Signal Transduct. Target 2021, 6, 53.

- Greber, U.F. Adenoviruses—Infection, pathogenesis and therapy. FEBS Lett. 2020, 594, 1818–1827.

- Muruve, D.A. The innate immune response to adenovirus vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2004, 15, 1157–1166.

- Chen, H.; Xiang, Z.Q.; Li, Y.; Kurupati, R.K.; Jia, B.; Bian, A.; Zhou, D.M.; Hutnick, N.; Yuan, S.; Gray, C.; et al. Adenovirus-based vaccines: Comparison of vectors from three species of adenoviridae. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 10522–10532.

- Ramamoorth, M.; Narvekar, A. Non viral vectors in gene therapy—An overview. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, GE01.

- Lin, L.T.; Richardson, C.D. The Host Cell Receptors for Measles Virus and Their Interaction with the Viral Hemagglutinin (H) Protein. Viruses 2016, 8, 250.

- Engeland, C.E.; Ungerechts, G. Measles Virus as an Oncolytic Immunotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 544.

- Lachmann, R. Herpes simplex virus-based vectors. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2004, 85, 177–190.

- Zu, H.; Gao, D. Non-viral Vectors in Gene Therapy: Recent Development, Challenges, and Prospects. AAPS J. 2021, 23, 78.

- Sung, Y.K.; Kim, S.W. Recent advances in the development of gene delivery systems. Biomater. Res. 2019, 23, 8.

- Mitchell, M.J.; Billingsley, M.M.; Haley, R.M.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A.; Langer, R. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2021, 20, 101–124.

- Al-Dosari, M.S.; Gao, X. Nonviral gene delivery: Principle, limitations, and recent progress. AAPS J. 2009, 11, 671–681.

- Zelmer, C.; Zweifel, L.P.; Kapinos, L.E.; Craciun, I.; Guven, Z.P.; Palivan, C.G.; Lim, R.Y.H. Organelle-specific targeting of polymersomes into the cell nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 2770–2778.

- Lee, S.W.; Kim, Y.M.; Cho, C.H.; Kim, Y.T.; Kim, S.M.; Hur, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, B.G.; Kim, S.C.; Ryu, H.S.; et al. An Open-Label, Randomized, Parallel, Phase II Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of a Cremophor-Free Polymeric Micelle Formulation of Paclitaxel as First-Line Treatment for Ovarian Cancer: A Korean Gynecologic Oncology Group Study (KGOG-3021). Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 50, 195–203.

- Palmerston Mendes, L.; Pan, J.; Torchilin, V.P. Dendrimers as Nanocarriers for Nucleic Acid and Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy. Molecules 2017, 22, 1401.

- Vines, J.B.; Yoon, J.H.; Ryu, N.E.; Lim, D.J.; Park, H. Gold Nanoparticles for Photothermal Cancer Therapy. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 167.

- Matulonis, U.A.; Sood, A.K.; Fallowfield, L.; Howitt, B.E.; Sehouli, J.; Karlan, B.Y. Ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16061.

- Oswald, A.J.; Gourley, C. Low-grade epithelial ovarian cancer: A number of distinct clinical entities? Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2015, 27, 412–419.

- Ayen, A.; Jimenez Martinez, Y.; Marchal, J.A.; Boulaiz, H. Recent Progress in Gene Therapy for Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1930.

- Shi, X.X.; Zhang, B.; Zang, J.L.; Wang, G.Y.; Gao, M.H. CD59 silencing via retrovirus-mediated RNA interference enhanced complement-mediated cell damage in ovary cancer. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2009, 6, 61–66.

- Rawlinson, J.W.; Vaden, K.; Hunsaker, J.; Miller, D.F.; Nephew, K.P. Adenoviral-delivered HE4-HSV-tk sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to ganciclovir. Gene Ther. Mol. Biol. 2013, 15, 120–130.

- Zhou, X.L.; Shi, Y.L.; Li, X. Inhibitory effects of the ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction-mediated herpes simplex virus-thymidine kinase/ganciclovir system on ovarian cancer in mice. Exp. Ther. Med. 2014, 8, 1159–1163.

- White, C.L.; Menghistu, T.; Twigger, K.R.; Searle, P.F.; Bhide, S.A.; Vile, R.G.; Melcher, A.A.; Pandha, H.S.; Harrington, K.J. Escherichia coli nitroreductase plus CB1954 enhances the effect of radiotherapy in vitro and in vivo. Gene Ther. 2008, 15, 424–433.

- Hartkopf, A.D.; Bossow, S.; Lampe, J.; Zimmermann, M.; Taran, F.A.; Wallwiener, D.; Fehm, T.; Bitzer, M.; Lauer, U.M. Enhanced killing of ovarian carcinoma using oncolytic measles vaccine virus armed with a yeast cytosine deaminase and uracil phosphoribosyltransferase. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 130, 362–368.

- Hanauer, J.R.; Gottschlich, L.; Riehl, D.; Rusch, T.; Koch, V.; Friedrich, K.; Hutzler, S.; Prufer, S.; Friedel, T.; Hanschmann, K.M.; et al. Enhanced lysis by bispecific oncolytic measles viruses simultaneously using HER2/neu or EpCAM as target receptors. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2016, 3, 16003.

- Goshima, F.; Esaki, S.; Luo, C.; Kamakura, M.; Kimura, H.; Nishiyama, Y. Oncolytic viral therapy with a combination of HF10, a herpes simplex virus type 1 variant and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for murine ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 134, 2865–2877.

- Thomas, E.D.; Meza-Perez, S.; Bevis, K.S.; Randall, T.D.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Langford, C.; Alvarez, R.D. IL-12 Expressing oncolytic herpes simplex virus promotes anti-tumor activity and immunologic control of metastatic ovarian cancer in mice. J. Ovarian Res. 2016, 9, 70.

- Sher, Y.P.; Chang, C.M.; Juo, C.G.; Chen, C.T.; Hsu, J.L.; Lin, C.Y.; Han, Z.; Shiah, S.G.; Hung, M.C. Targeted endostatin-cytosine deaminase fusion gene therapy plus 5-fluorocytosine suppresses ovarian tumor growth. Oncogene 2013, 32, 1082–1090.

- Hu, W.; Wang, J.; Dou, J.; He, X.; Zhao, F.; Jiang, C.; Yu, F.; Hu, K.; Chu, L.; Li, X.; et al. Augmenting therapy of ovarian cancer efficacy by secreting IL-21 human umbilical cord blood stem cells in nude mice. Cell Transplant. 2011, 20, 669–680.

- Fewell, J.G.; Matar, M.M.; Rice, J.S.; Brunhoeber, E.; Slobodkin, G.; Pence, C.; Worker, M.; Lewis, D.H.; Anwer, K. Treatment of disseminated ovarian cancer using nonviral interleukin-12 gene therapy delivered intraperitoneally. J. Gene Med. 2009, 11, 718–728.

- Bai, Y.; Gou, M.; Yi, T.; Yang, L.; Liu, L.; Lin, X.; Su, D.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, X. Efficient Inhibition of Ovarian Cancer by Gelonin Toxin Gene Delivered by Biodegradable Cationic Heparin-polyethyleneimine Nanogels. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 12, 397–406.

- Huang, Y.H.; Zugates, G.T.; Peng, W.; Holtz, D.; Dunton, C.; Green, J.J.; Hossain, N.; Chernick, M.R.; Padera, R.F., Jr.; Langer, R.; et al. Nanoparticle-delivered suicide gene therapy effectively reduces ovarian tumor burden in mice. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 6184–6191.

- Lu, J.; Getz, G.; Miska, E.A.; Alvarez-Saavedra, E.; Lamb, J.; Peck, D.; Sweet-Cordero, A.; Ebert, B.L.; Mak, R.H.; Ferrando, A.A.; et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature 2005, 435, 834–838.

- Chen, S.N.; Chang, R.; Lin, L.T.; Chern, C.U.; Tsai, H.W.; Wen, Z.H.; Li, Y.H.; Li, C.J.; Tsui, K.H. MicroRNA in Ovarian Cancer: Biology, Pathogenesis, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1510.

- Iorio, M.V.; Visone, R.; Di Leva, G.; Donati, V.; Petrocca, F.; Casalini, P.; Taccioli, C.; Volinia, S.; Liu, C.G.; Alder, H.; et al. MicroRNA signatures in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 8699–8707.

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424.

- Ayen, A.; Jimenez Martinez, Y.; Boulaiz, H. Targeted Gene Delivery Therapies for Cervical Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 1301.

- Yan, C.M.; Zhao, Y.L.; Cai, H.Y.; Miao, G.Y.; Ma, W. Blockage of PTPRJ promotes cell growth and resistance to 5-FU through activation of JAK1/STAT3 in the cervical carcinoma cell line C33A. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 1737–1744.

- Zhou, S.; Xiao, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yang, H.; Xie, C.; Zhou, F.; Zhou, Y. Knockdown of homeobox containing 1 increases the radiosensitivity of cervical cancer cells through telomere shortening. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 515–521.

- Lv, X.F.; Hong, H.Q.; Liu, L.; Cui, S.H.; Ren, C.C.; Li, H.Y.; Zhang, X.A.; Zhang, L.D.; Wei, T.X.; Liu, J.J.; et al. RNAimediated downregulation of asparaginaselike protein 1 inhibits growth and promotes apoptosis of human cervical cancer line SiHa. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 931–937.

- Qi, L.; Xing, L.N.; Wei, X.; Song, S.G. Effects of VEGF suppression by small hairpin RNA interference combined with radiotherapy on the growth of cervical cancer. Genet. Mol. Res. 2014, 13, 5094–5106.

- Jin, B.Y.; Campbell, T.E.; Draper, L.M.; Stevanovic, S.; Weissbrich, B.; Yu, Z.; Restifo, N.P.; Rosenberg, S.A.; Trimble, C.L.; Hinrichs, C.S. Engineered T cells targeting E7 mediate regression of human papillomavirus cancers in a murine model. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e99488.

- U.S National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- Li, Y.; Zhang, M.C.; Xu, X.K.; Zhao, Y.; Mahanand, C.; Zhu, T.; Deng, H.; Nevo, E.; Du, J.Z.; Chen, X.Q. Functional Diversity of p53 in Human and Wild Animals. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 152.

- Nakamura, M.; Obata, T.; Daikoku, T.; Fujiwara, H. The Association and Significance of p53 in Gynecologic Cancers: The Potential of Targeted Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5482.

- Doorbar, J. Molecular biology of human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer. Clin. Sci. 2006, 110, 525–541.

- Jia, H.; Kling, J. China offers alternative gateway for experimental drugs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 117–118.

- Su, X.; Chen, W.J.; Xiao, S.W.; Li, X.F.; Xu, G.; Pan, J.J.; Zhang, S.W. Effect and Safety of Recombinant Adenovirus-p53 Transfer Combined with Radiotherapy on Long-Term Survival of Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer. Hum. Gene Ther. 2016, 27, 1008–1014.

- Kajitani, K.; Honda, K.; Terada, H.; Yasui, T.; Sumi, T.; Koyama, M.; Ishiko, O. Human Papillomavirus E6 Knockdown Restores Adenovirus Mediated-estrogen Response Element Linked p53 Gene Transfer in HeLa Cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 8239–8245.

- Liu, Y.G.; Zheng, X.L.; Liu, F.M. The mechanism and inhibitory effect of recombinant human P53 adenovirus injection combined with paclitaxel on human cervical cancer cell HeLa. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 1037–1042.

- Liu, B.; Han, S.M.; Tang, X.Y.; Han, L.; Li, C.Z. Cervical cancer gene therapy by gene loaded PEG-PLA nanomedicine. Asian. Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 4915–4918.

- Wu, M.; Gunning, W.; Ratnam, M. Expression of folate receptor type alpha in relation to cell type, malignancy, and differentiation in ovary, uterus, and cervix. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1999, 8, 775–782.

- Yang, Y.; He, L.; Liu, Y.; Xia, S.; Fang, A.; Xie, Y.; Gan, L.; He, Z.; Tan, X.; Jiang, C.; et al. Promising Nanocarriers for PEDF Gene Targeting Delivery to Cervical Cancer Cells Mediated by the Over-expressing FRalpha. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32427.

- Hu, Z.; Ding, W.; Zhu, D.; Yu, L.; Jiang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Ji, T.; Liu, D.; et al. TALEN-mediated targeting of HPV oncogenes ameliorates HPV-related cervical malignancy. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 425–436.

- Ling, K.; Yang, L.; Yang, N.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Liang, S.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Yan, P.; Liang, Z. Gene Targeting of HPV18 E6 and E7 Synchronously by Nonviral Transfection of CRISPR/Cas9 System in Cervical Cancer. Hum. Gene Ther. 2020, 31, 297–308.

- Gao, C.; Wu, P.; Yu, L.; Liu, L.; Liu, H.; Tan, X.; Wang, L.; Huang, X.; Wang, H. The application of CRISPR/Cas9 system in cervical carcinogenesis. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021, 29, 466–474.

- Cheng, H.Y.; Zhang, T.; Qu, Y.; Shi, W.J.; Lou, G.; Liu, Y.X.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Cheng, L. Synergism between RIZ1 gene therapy and paclitaxel in SiHa cervical cancer cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2016, 23, 392–395.

- Banno, K.; Iida, M.; Yanokura, M.; Kisu, I.; Iwata, T.; Tominaga, E.; Tanaka, K.; Aoki, D. MicroRNA in cervical cancer: OncomiRs and tumor suppressor miRs in diagnosis and treatment. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 178075.

- Tornesello, M.L.; Faraonio, R.; Buonaguro, L.; Annunziata, C.; Starita, N.; Cerasuolo, A.; Pezzuto, F.; Tornesello, A.L.; Buonaguro, F.M. The Role of microRNAs, Long Non-coding RNAs, and Circular RNAs in Cervical Cancer. Front Oncol. 2020, 10, 150.

- Long, M.J.; Wu, F.X.; Li, P.; Liu, M.; Li, X.; Tang, H. MicroRNA-10a targets CHL1 and promotes cell growth, migration and invasion in human cervical cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2012, 324, 186–196.

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, W.; Gulina, K. Correlation between miR-19a inhibition and radiosensitivity in SiHa cervical cancer cells. J. BUON 2017, 22, 1505–1508.

- Kang, H.W.; Wang, F.; Wei, Q.; Zhao, Y.F.; Liu, M.; Li, X.; Tang, H. miR-20a promotes migration and invasion by regulating TNKS2 in human cervical cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 897–904.

- Yao, Q.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Zhou, H.; Qu, L.H. MicroRNA-21 promotes cell proliferation and down-regulates the expression of programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) in HeLa cervical carcinoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 388, 539–542.

- Peralta-Zaragoza, O.; Deas, J.; Meneses-Acosta, A.; De la O-Gómez, F.; Fernandez-Tilapa, G.; Gomez-Ceron, C.; Benitez-Boijseauneau, O.; Burguete-Garcia, A.; Torres-Poveda, K.; Bermudez-Morales, V.H.; et al. Relevance of miR-21 in regulation of tumor suppressor gene PTEN in human cervical cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 215.

- Brooks, R.A.; Fleming, G.F.; Lastra, R.R.; Lee, N.K.; Moroney, J.W.; Son, C.H.; Tatebe, K.; Veneris, J.L. Current recommendations and recent progress in endometrial cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 258–279.

- Boyd, J. Molecular biology in the clinicopathologic assessment of endometrial carcinoma subtypes. Gynecol. Oncol. 1996, 61, 163–165.

- Ramondetta, L.; Mills, G.B.; Burke, T.W.; Wolf, J.K. Adenovirus-mediated expression of p53 or p21 in a papillary serous endometrial carcinoma cell line (SPEC-2) results in both growth inhibition and apoptotic cell death: Potential application of gene therapy to endometrial cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 278–284.

- Ural, A.U.; Takebe, N.; Adhikari, D.; Ercikan-Abali, E.; Banerjee, D.; Barakat, R.; Bertino, J.R. Gene therapy for endometrial carcinoma with the herpes simplex thymidine kinase gene. Gynecol. Oncol. 2000, 76, 305–310.

- Grundker, C.; Huschmand Nia, A.; Emons, G. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor-targeted gene therapy of gynecologic cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2005, 4, 225–231.

- Xia, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, W. Applications of Recombinant Adenovirus-p53 Gene Therapy for Cancers in the Clinic in China. Curr. Gene Ther. 2020, 20, 127–141.

- Maxwell, G.L.; Chandramouli, G.V.; Dainty, L.; Litzi, T.J.; Berchuck, A.; Barrett, J.C.; Risinger, J.I. Microarray analysis of endometrial carcinomas and mixed mullerian tumors reveals distinct gene expression profiles associated with different histologic types of uterine cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 4056–4066.

- Maurice-Duelli, A.; Ndoye, A.; Bouali, S.; Leroux, A.; Merlin, J.L. Enhanced cell growth inhibition following PTEN nonviral gene transfer using polyethylenimine and photochemical internalization in endometrial cancer cells. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2004, 3, 459–465.

- Banno, K.; Yanokura, M.; Kisu, I.; Yamagami, W.; Susumu, N.; Aoki, D. MicroRNAs in endometrial cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 18, 186–192.

- Donkers, H.; Bekkers, R.; Galaal, K. Diagnostic value of microRNA panel in endometrial cancer: A systematic review. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 2010–2023.

- Evans, P.; Brunsell, S. Uterine fibroid tumors: Diagnosis and treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2007, 75, 1503–1508.

- Hassan, M.H.; Khatoon, N.; Curiel, D.T.; Hamada, F.M.; Arafa, H.M.; Al-Hendy, A. Toward gene therapy of uterine fibroids: Targeting modified adenovirus to human leiomyoma cells. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 514–524.

- Niu, H.; Simari, R.D.; Zimmermann, E.M.; Christman, G.M. Nonviral vector-mediated thymidine kinase gene transfer and ganciclovir treatment in leiomyoma cells. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 91, 735–740.

- Al-Hendy, A.; Lee, E.J.; Wang, H.Q.; Copland, J.A. Gene therapy of uterine leiomyomas: Adenovirus-mediated expression of dominant negative estrogen receptor inhibits tumor growth in nude mice. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 191, 1621–1631.

- Nair, S.; Curiel, D.T.; Rajaratnam, V.; Thota, C.; Al-Hendy, A. Targeting adenoviral vectors for enhanced gene therapy of uterine leiomyomas. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 2398–2406.

- Abdelaziz, M.; Sherif, L.; ElKhiary, M.; Nair, S.; Shalaby, S.; Mohamed, S.; Eziba, N.; El-Lakany, M.; Curiel, D.; Ismail, N.; et al. Targeted Adenoviral Vector Demonstrates Enhanced Efficacy for In Vivo Gene Therapy of Uterine Leiomyoma. Reprod. Sci. 2016, 23, 464–474.

- Deng, Y.; Han, Q.; Mei, S.; Li, H.; Yang, F.; Wang, J.; Ge, S.; Jing, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, T. Cyclin-dependent kinase subunit 2 overexpression promotes tumor progression and predicts poor prognosis in uterine leiomyosarcoma. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 2845–2852.

- Li, Y.; Qiang, W.; Griffin, B.B.; Gao, T.; Chakravarti, D.; Bulun, S.; Kim, J.J.; Wei, J.J. HMGA2-mediated tumorigenesis through angiogenesis in leiomyoma. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 114, 1085–1096.

- Giudice, L.C.; Kao, L.C. Endometriosis. Lancet 2004, 364, 1789–1799.

- Dabrosin, C.; Gyorffy, S.; Margetts, P.; Ross, C.; Gauldie, J. Therapeutic effect of angiostatin gene transfer in a murine model of endometriosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 161, 909–918.

- Sun, J.J.; Yin, L.R.; Mi, R.R.; Ma, H.D.; Guo, S.J.; Shi, Y.; Gu, Y.J. Human endostatin antiangiogenic gene therapy mediated by recombinant adeno-associated virus vector in nude mouse with endometriosis. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2010, 45, 45–50.

- Wang, N.; Liu, B.; Liang, L.; Wu, Y.; Xie, H.; Huang, J.; Guo, X.; Tan, J.; Zhan, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Antiangiogenesis therapy of endometriosis using PAMAM as a gene vector in a noninvasive animal model. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 546479.

- Othman, E.E.; Salama, S.; Ismail, N.; Al-Hendy, A. Toward gene therapy of endometriosis: Adenovirus-mediated delivery of dominant negative estrogen receptor genes inhibits cell proliferation, reduces cytokine production, and induces apoptosis of endometriotic cells. Fertil. Steril. 2007, 88, 462–471.

- Othman, E.E.; Zhu, Z.B.; Curiel, D.T.; Khatoon, N.; Salem, H.T.; Khalifa, E.A.; Al-Hendy, A. Toward gene therapy of endometriosis: Transductional and transcriptional targeting of adenoviral vectors to endometriosis cells. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 199, 117.e1–117.e6.

- Koippallil Gopalakrishnan, A.R.; Pandit, H.; Metkari, S.M.; Warty, N.; Madan, T. Adenoviral vector encoding soluble Flt-1 engineered human endometrial mesenchymal stem cells effectively regress endometriotic lesions in NOD/SCID mice. Gene Ther. 2016, 23, 580–591.

- Senut, M.C.; Suhr, S.T.; Gage, F.H. Gene transfer to the rodent placenta in situ. A new strategy for delivering gene products to the fetus. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 1565–1571.

- Xing, A.; Boileau, P.; Cauzac, M.; Challier, J.C.; Girard, J.; Hauguel-de Mouzon, S. Comparative in vivo approaches for selective adenovirus-mediated gene delivery to the placenta. Hum. Gene Ther. 2000, 11, 167–177.

- Heikkila, A.; Hiltunen, M.O.; Turunen, M.P.; Keski-Nisula, L.; Turunen, A.M.; Rasanen, H.; Rissanen, T.T.; Kosma, V.M.; Manninen, H.; Heinonen, S.; et al. Angiographically guided utero-placental gene transfer in rabbits with adenoviruses, plasmid/liposomes and plasmid/polyethyleneimine complexes. Gene Ther. 2001, 8, 784–788.

- Bagot, C.N.; Troy, P.J.; Taylor, H.S. Alteration of maternal Hoxa10 expression by in vivo gene transfection affects implantation. Gene Ther. 2000, 7, 1378–1384.

- Taylor, H.S.; Arici, A.; Olive, D.; Igarashi, P. HOXA10 is expressed in response to sex steroids at the time of implantation in the human endometrium. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 1379–1384.

- Luo, F.; Wen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, Z. Roles of long non-coding RNAs in cervical cancer. Life Sci. 2020, 256, 117981.

- Shi, Y.; He, R.; Yang, Y.; He, Y.; Shao, K.; Zhan, L.; Wei, B. Circular RNAs: Novel biomarkers for cervical, ovarian and endometrial cancer (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2020, 44, 1787–1798.