| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kazuhisa Maeda | -- | 2302 | 2022-08-06 07:05:12 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | + 1 word(s) | 2303 | 2022-08-08 04:35:23 | | |

Video Upload Options

Japanese pharmaceutical cosmetics, often referred to as quasi-drugs, contain skin-lightening active ingredients formulated to prevent sun-induced pigment spots and freckles. Their mechanisms of action include suppressing melanin production in melanocytes and promoting epidermal growth to eliminate melanin more rapidly. For example, arbutin and rucinol are representative skin-lightening active ingredients that inhibit melanin production, and disodium adenosine monophosphate and dexpanthenol are skin-lightening active ingredients that inhibit melanin accumulation in the epidermis. In contrast, oral administration of vitamin C and tranexamic acid in pharmaceutical products can lighten freckles and melasma, and these products are more effective than quasi-drugs. On the basis of their clinical effectiveness, skin-lightening active ingredients can be divided into four categories according to their effectiveness and adverse effects.

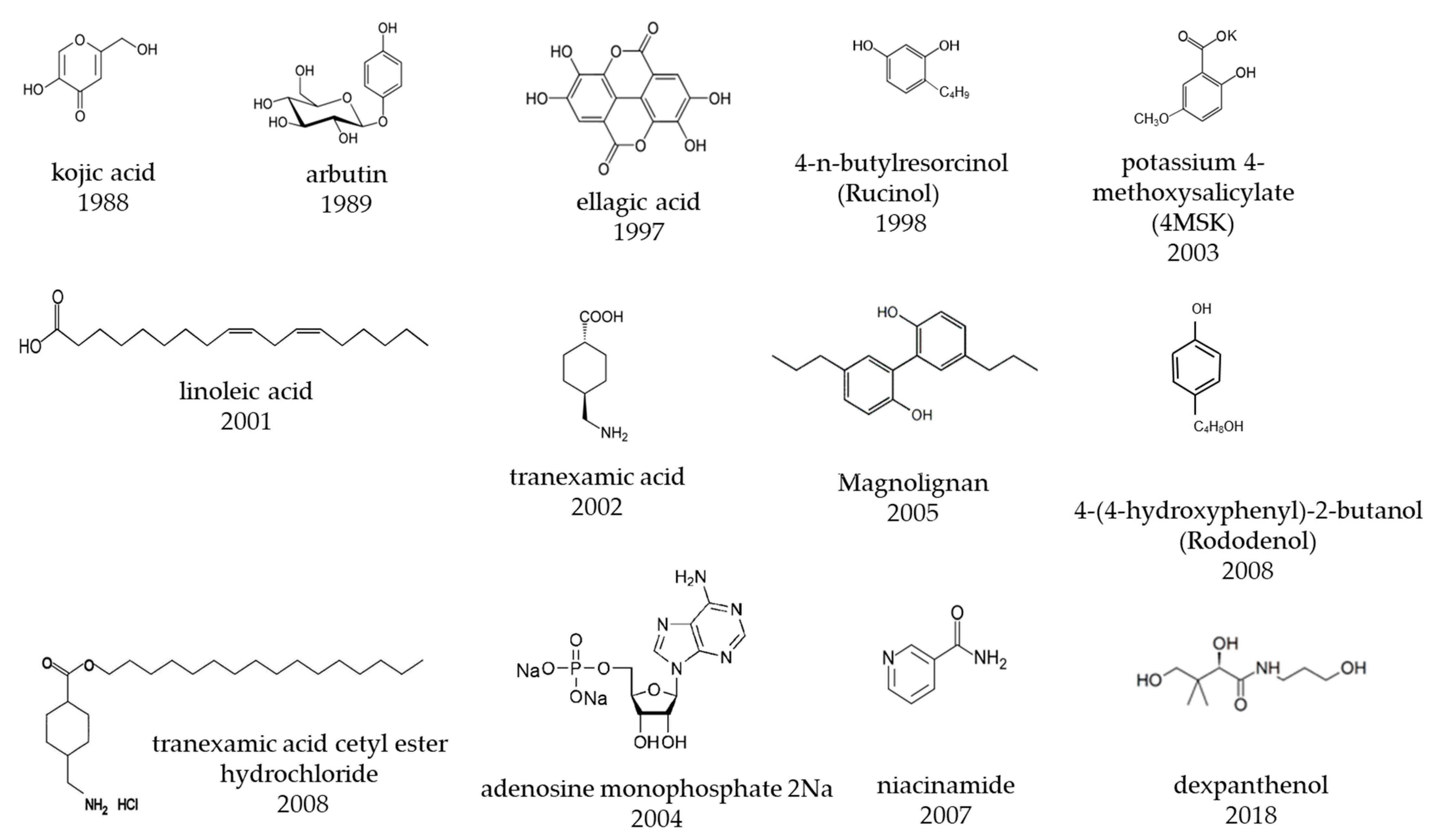

1. Development of Skin-Lightening Active Ingredients

| Approved Year | Generic Name | Development Company | Chemical Name/Substance Name | Main Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| placenta extract | ||||

| 1983 | magnesium ascorbyl phosphate (APM) | Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. | magnesium L-ascorbyl-2-phosphate | tyrosinase inhibition |

| 1988 | kojic acid | Sansho Seiyaku Co., Ltd. | kojic acid | tyrosinase inhibition |

| 1989 | arbutin | Shiseido Co., Ltd. | hydroquinone-β-D-glucopyranoside | tyrosinase inhibition |

| 1994 | ascorbyl glucoside (AA-2G) | Hayashibara Co., Ltd., Kaminomoto Co., Ltd., Shiseido Co., Ltd. | L- ascorbic acid 2-O-α-glucoside | tyrosinase inhibition |

| 1997 | ellagic acid | Lion Corporation | ellagic acid | tyrosinase inhibition |

| 1998 | Rucinol® | Kurarey Co., Ltd. POLA Chemical industries, Inc. |

4-n-butylresorcinol | tyrosinase inhibition |

| 1999 | Chamomile ET | Kao Corporation | Matricaria chamomilla L Extract | endothelin blocker |

| 2001 | linoleic acid S | Sunstar Inc. | linoleic acid | tyrosinase degradation, stimulation of epidermal turn over |

| 2002 | tranexamic acid (t-AMCHA) |

Shiseido Co., Ltd. | trans-4-aminocyclohexane carboxylic acid | inhibition of prostaglandin E2 production by anti-plasmin |

| 2003 | 4MSK | Shiseido Co., Ltd. | potassium 4-methoxysalicylate | tyrosinase inhibition |

| 2004 | Vitamin C ethyl | Nippon Hypox Laboratories, Inc. | 3-O-ethyl ascorbic acid | tyrosinase inhibition |

| 2004 | Energy signal AMP® | Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. | adenosine mono phosphate | stimulation of epidermal turnover |

| 2005 | Magnolignan® | Kanebo Cosmetics Inc. | 5,5-dipropyl-biphenyl-2,2-diol | inhibition of tyrosinase maturation, cytotoxicity to melanocytes |

| 2007 | D-Melano (niacinamide W) | P&G Maxfactor | niacinamide | suppression of melanosome transfer |

| 2008 | Rhododenol® | Kanebo Cosmetics Inc. | 4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-butanol, Rhododendrol | tyrosinase inhibition, cytotoxicity of melanocytes |

| 2008 | TXC | CHANEL | tranexamic acid cetyl ester hydrochloride | inhibition of prostaglandin E2 production |

| 2009 | ascorbyl tetraisopalmitate | Nikko Chemicals Co., Ltd. | ascorbyl tetra-2-hexyldecanoate | tyrosinase inhibition |

| 2018 | dexpanthenol W (PCE–DP) | POLA ORBIS Holdings Inc. | dexpanthenol | enhance energy production of epidermal cells |

2. Report on the Effectiveness of a Formulation Containing a Lightening Agent and a Spot Remedy for Senile Pigmented Lesions

| 10% Magnesium Ascorbyl Phosphate Formulation | 7% Arbutin Formulation | 0.5% Ellagic Acid Formulation | 1% Kojic Acid and 0.1% Oil-Soluble Licorice Extract Formulation | 2% 4-Hydroxyanisole and 0.01% Vitamin A Acid Formulation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test design | Open study | Open study | Open study | Open study | Double-blind controlled study | ||

| Number of cases | 17 | 16 | 13 | 18 | 420 | 421 | |

| Sex | – | – | Women | 5 men, 13 women | Men and women | ||

| Age | – | – | Unknown | 28–50 years old (average 39 years old) | 34–85 years old (average 62.6 years old) | ||

| Location | – | – | Unknown | Face | Forearm | Face | |

| Period | – | 3 months to 1 year | 1 to 3 months | 8 and 16 weeks | 24 weeks | Observation up to 48 weeks after 24 weeks of application | |

| Effectiveness judgment | Skin color value (color difference meter) | Visual observation | Visual observation | Close-up photograph determination and skin color value (image analysis) | Visual observation | Visual observation | |

| Effectiveness ratio | Effective (improved or much improved) or higher | 58.80% | 3 months 0%, 6 months 15.4%, 1 year 66.7% |

30.80% | 8 weeks 5.6%, 16 weeks 22.2% |

52.60% | 56.30% |

| Slightly effective (slightly improved) or more | 88.20% | 3 months 81.2%, 6 months 100%, 1 year 100% |

69.20% | 8 weeks 66.7%, 16 weeks 77.8% |

79.30% | 84.10% | |

| Adverse effects | – | None | None | Irritation in a few cases, but no serious adverse effects | Redness 56%, burning 34%, desquamation 24%, itching 16%, irritation 7%, decoloration 9%. |

– | |

| References | [7] | [8] | [9] | [10] | [6] | [6] | |

3. Effectiveness Indices of Lightening Ingredients Developed in Japan

| Effectiveness Indices | Skin-Lightening Ingredients | Test Concentration (%) | General Purpose or Japanese Cosmetics Company | Scientific Articles Providing Evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Effectiveness of same concentration of cosmetic formulations on human pigment spots has been published in scientific journals and is highly recommended. | tranexamic acid | 2 | General purpose | [12] |

| arbutin | 3 | General purpose | [13] | ||

| 3-O-ethyl ascorbic acid (vitamin C ethyl) | 1 | General purpose | [14] | ||

| magnesium L-ascorbyl-2-phosphate (APM) | 3 | General purpose | [15] | ||

| ellagic acid | 0.5 | General purpose | [9] | ||

| kojic acid | 2.5, 0.5 | General purpose | [16][17] | ||

| linoleic acid | 0.1 | General purpose | [18] | ||

| 4-n-butyl resorcinol, | 0.3 | General purpose | [19] | ||

| chamomile extract | 0.5 | Kao Corporation | [20] | ||

| adenosine monophosphate | 3 | Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. | [21] | ||

| B | Effectiveness of higher concentrations than those used in cosmetics on human pigment spots has been published in scientific journals and is recommended. | oil-soluble licorice extract containing 50% glabridin | 0.2 | General purpose | [22] |

| niacinamide | 5, 4 | General purpose | [23][24] | ||

| placenta extract | 3 | General purpose | [25] | ||

| retinol | 0.15 | General purpose | [26] | ||

| ascorbic acid 2-O-α-glucoside (AA-2G) | 20 (iontophoresis) | General purpose | [27] | ||

| azelaic acid. | 20 | General purpose | [28] | ||

| C | No effectiveness for human pigment spots has been published in scientific journals and may be considered, but evidence is insufficient | potassium 4-methoxysalicylate | 1, 3 | Shiseido Co. Ltd. | |

| dexpanthenol | POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. | ||||

| D | Not recommended, because of toxicity data published in scientific journals | Rhododenol | 2 | Kanebo Cosmetics Inc. | [29] |

| Magnolignan | 0.5 | Kanebo Cosmetics Inc. | [29] | ||

| ascorbyl tetra-2-hexyldecanoate | Nikko Chemicals Co. Ltd. | [30][31][32] | |||

References

- General chapter. Functional Cosmetics Marketing Handbook 2019–2020; Fuji Keizai Group Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; pp. 7–32. (In Japanese)

- Olsen, E.A.; Katz, H.I.; Levine, N.; Shupack, J.; Billys, M.M.; Prawer, S.; Gold, J.; Stiller, M.; Lufrano, L.; Thorne, E.G. Tretinoin emollient cream: A new therapy for photodamaged skin. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1992, 26, 215–224.

- Griffiths, C.E.; Finkel, L.J.; Ditre, C.M.; Hamilton, T.A.; Ellis, C.N.; Voorhees, J.J. Topical tretinoin (retinoic acid) improves melasma. A vehicle-controlled, clinical trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 1993, 129, 415–421.

- Griffiths, C.E.; Goldfarb, M.T.; Finkel, L.J.; Roulia, V.; Bonawitz, M.; Hamilton, T.A.; Ellis, C.N.; Voorhees, J.J. Topical tretinoin (retinoic acid) treatment of hyperpigmented lesions associated with photoaging in Chinese and Japanese patients: A vehicle-controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1994, 30, 76–84.

- Jarratt, M. Mequinol 2%/tretinoin 0.01% solution: An effective and safe alternative to hydroquinone 3% in the treatment of solar lentigines. Cutis 2004, 74, 319–322.

- Fleischer, A.B., Jr.; Schwartzel, E.H.; Colby, S.I.; Altman, D.J. The combination of 2% 4-hydroxyanisole (Mequinol) and 0.01% tretinoin is effective in improving the appearance of solar lentigines and related hyperpigmented lesions in two double-blind multicenter clinical studies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2000, 42, 459–467.

- Kameyama, K.; Sakai, C.; Kondoh, S.; Yonemoto, K.; Nishiyama, S.; Tagawa, M.; Murata, T.; Ohnuma, T.; Quigley, J.; Dorsky, A.; et al. Inhibitory effect of magnesium L-ascorbyl-2-phosphate (VC-PMG) on melanogenesis in vitro and in vivo. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1996, 34, 29–33.

- Naganuma, M. Whitening cosmetics and its effectiveness in Japan. Ski. Surg. 1999, 8, 2–7. (In Japanese)

- Yokoyama, M. Clinical evaluation of the use of whitening cream containing ellagic acid for the treatment of skin pigmentation conditions. Ski. Res. 2001, 43, 286–291. (In Japanese)

- Harada, T. Clinical evaluation of whitening cream containing kojic acid and oil-soluble licorice extract for senile pigment fleckle on the face. Ski. Res. 2000, 42, 270–275. (In Japanese)

- Koide, C.; Suzuki, T.; Mizutani, Y.; Hori, K.; Nakajima, A.; Uchiwa, H.; Sasaki, M.; Ifuku, O.; Maeda, K.; Iwabuchi, H.; et al. A questionnaire on pigmented disorders and use of whitening cosmetics in Japanese women. J. Jpn. Cosmet. Sci. Soc. 2006, 30, 306–310. (In Japanese)

- Kondo, S.; Okada, Y.; Tomita, Y. Clinical study of effect of tranexamic acid emulsion on melasma and freckles. Ski. Res. 2007, 6, 309–315. (In Japanese)

- Sugai, T. Clinical effects of arbutin in patients with chloasma. Ski. Res. 1992, 34, 522–529. (In Japanese)

- Miki, S.; Nishikawa, H. Effectiveness of vitamin C ethyl, Anti-Aging Series 2; N.T.S.: Tokyo, Japan, 2006; pp. 265–278. (In Japanese)

- Ichikawa, H.; Kawase, H.; Aso, K.; Takeuchi, K. Topical treatment f pigmented dermatoses by modified ascorbic acid. Jpn. J. Clin. Dermatol. 1969, 23, 327–331. (In Japanese)

- Mishima, Y.; Ohyama, Y.; Shibata, T.; Seto, H.; Hatae, S. Inhibitory action of kojic acid on melanogenesis and its therapeutic effect for various human hyper-pigmentation disorders. Ski. Res. 1994, 36, 134–150. (In Japanese)

- Nakayama, H.; Sakurai, M.; Kume, A.; Hanada, S.; Iwanaga, A. The effect of kojic acid application on various facial pigmentary disorders. Nishinihon J. Dermatol. 1994, 56, 1172–1181. (In Japanese)

- Clinical trial group for linoleic acid-containing gel. Clinical trial for liver spots using a linoleic acid-containing gel. Nishinihon J. Dermatol. 1998, 60, 537–542. (In Japanese)

- Harada, S.; Matsushima, T.; Toda, K.; Takemura, T.; Kawashima, M.; Sugawara, M.; Mizuno, J.; Iijima, M.; Miyakawa, S. Efficacy of rusinol (4-n-butylresorcinol) on chloasma. Nishinihon J. Dermatol. 1999, 61, 813–819. (In Japanese)

- Kawashima, M.; Imokawa, G. Mechanism of pigment enhancement in UVB-induced melanosis and lentigo senilis, and anti-spot effect of Chamomile ET. Mon. Book Derma 2005, 98, 43–61. (In Japanese)

- Kawashima, M.; Mizuno, A.; Murata, Y. Improvement of hyperpigmentation based on accelerated epidermal turnover: Clinical effects of disodium adenosine monophosphate in patients with melasma. Jpn. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2008, 62, 250–257. (In Japanese)

- Haramoto, I.; Mizoguchi, M. Clinical evaluation of oil-soluble licorice extracts cream on chloasma. Nishinihon J. Dermatol. 1995, 57, 601–608. (In Japanese)

- Hakozaki, T.; Minwalla, L.; Zhuang, J.; Chhoa, M.; Matsubara, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Greatens, A.; Hillebrand, G.G.; Bissett, D.L.; Boissy, R.E. The effect of niacinamide on reducing cutaneous pigmentation and suppression of melanosome transfer. Br. J. Dermatol. 2002, 147, 20–31.

- Navarrete-Solís, J.; Castanedo-Cázares, J.P.; Torres-Álvarez, B.; Oros-Ovalle, C.; Fuentes-Ahumada, C.; González, F.J.; Martínez-Ramírez, J.D.; Moncada, B. A double-blind, randomized clinical trial of niacinamide 4% versus hydroquinone 4% in the treatment of melasma. Derm. Res. Pract. 2011, 2011, 379173.

- Shimokawa, Y.; Kamisasanuki, S.; Tashiro, M. Treatment of facial dysmelanosis with cosmetics containing Placen A. Nishinihon J. Dermatol. 1982, 44, 1027–1029. (In Japanese)

- Tucker-Samaras, S.; Zedayko, T.; Cole, C.; Miller, D.; Wallo, W.; Leyden, J.J. A stabilized 0.1% retinol facial moisturizer improves the appearance of photodamaged skin in an eight-week, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2009, 8, 932–936.

- Taylor, M.B.; Yanaki, J.S.; Draper, D.O.; Shurtz, J.C.; Coglianese, M. Successful short-term and long-term treatment of melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation using vitamin C with a full-face iontophoresis mask and a mandelic/malic acid skin care regimen. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2013, 12, 45–50.

- Verallo-Rowell, V.M.; Verallo, V.; Graupe, K.; Lopez-Villafuerte, L.; Garcia-Lopez, M. Double-blind comparison of azelaic acid and hydroquinone in the treatment of melasma. Acta. Derm. Venereol. Suppl. 1989, 143, 58–61.

- Gu, L.; Zeng, H.; Takahashi, T.; Maeda, K. In vitro methods for predicting chemical leukoderma caused by quasi-drug cosmetics. Cosmetics 2017, 4, 31.

- Swinnen, I.; Goossens, A. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by ascorbyl tetraisopalmitate. Contact Dermat. 2011, 64, 241–242.

- Assier, H.; Wolkenstein, P.; Grille, C.; Chosidow, O. Contact dermatitis caused by ascorbyl tetraisopalmitate in a cream used for the management of atopic dermatitis. Contact Dermat. 2014, 71, 60–61.

- Scheman, A.; Fournier, E.; Kerchinsky, L. Allergic contact dermatitis to two eye creams containing tetrahexyldecyl ascorbate. Contact Dermat. 2022, 86, 556–557.

- Tagawa, M.; Murata, T.; Onuma, T.; Kameyama, K.; Sakai, C.; Kondo, S.; Yonemoto, K.; Quigley, J.; Dorsky, A.; Bucks, D.; et al. Inhibitory effects of magnesium ascorbyl phosphate on melanogenesis. SCCJ J. 1993, 27, 409–414. (In Japanese)

- Yamamoto, K.; Ebihara, T.; Nakayama, H.; Okubo, A.; Higa, Y. The result of long term use test of kojic acid mixture pharmaceutical. Nishinihon J. Dermatol. 1998, 60, 849–852. (In Japanese)