| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andreea Andronesi | -- | 1772 | 2022-08-05 10:45:30 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 1772 | 2022-08-05 10:54:19 | | | | |

| 3 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 1772 | 2022-08-05 10:55:23 | | | | |

| 4 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 1772 | 2022-08-08 08:57:49 | | |

Video Upload Options

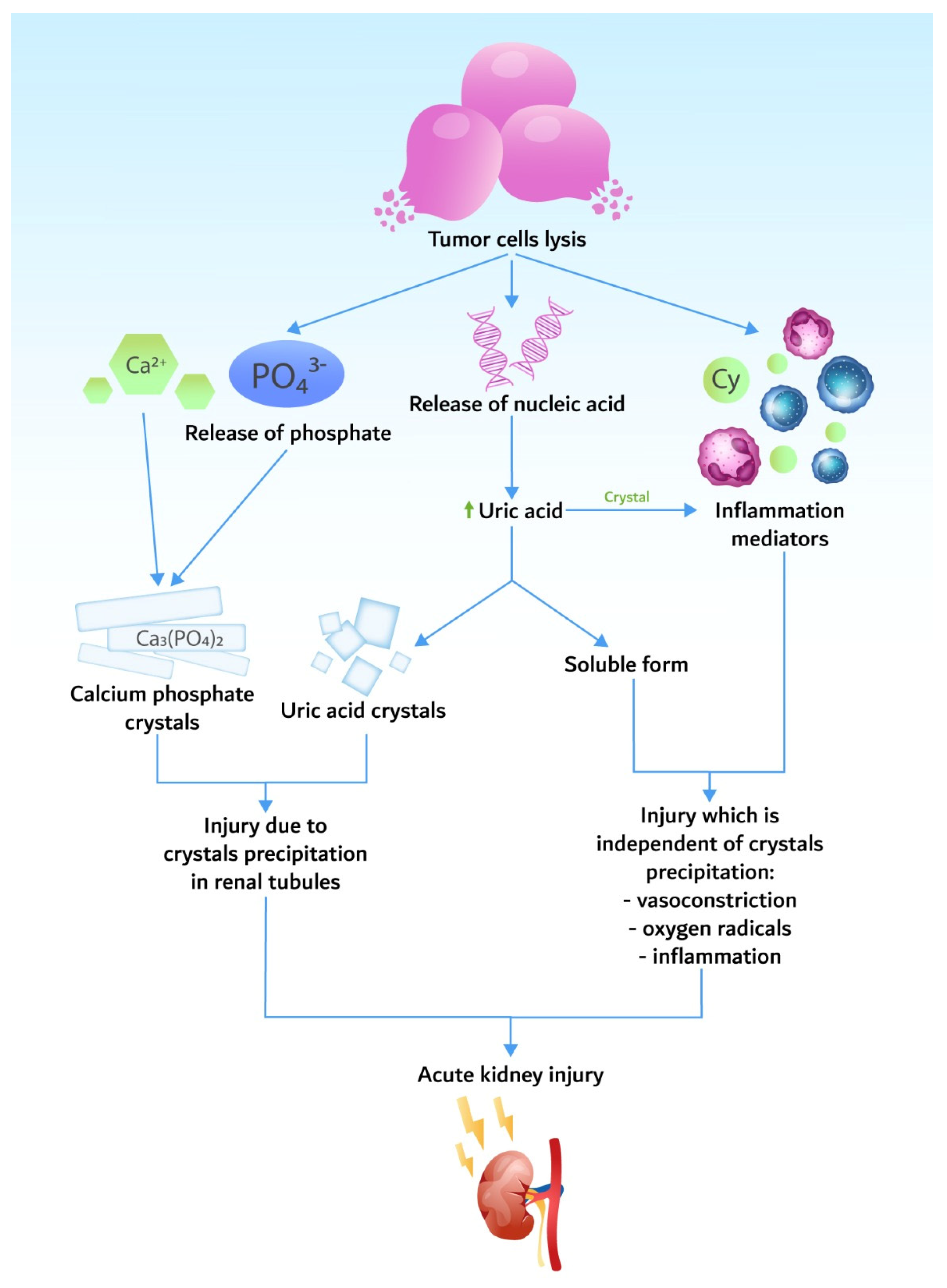

Tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) is a common cause of acute kidney injury in patients with malignancies, and it is a frequent condition for which the nephrologist is consulted in the case of the hospitalized oncological patient. Recognizing the patients at risk of developing TLS is essential, and so is the prophylactic treatment. The initiation of treatment for TLS is a medical emergency that must be addressed in a multidisciplinary team (oncologist, nephrologist, critical care physician) in order to reduce the risk of death and that of chronic renal impairment. TLS can occur spontaneously in the case of high tumor burden or may be caused by the initiation of highly efficient anti-tumor therapies, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, dexamethasone, monoclonal antibodies, CAR-T therapy, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. It is caused by lysis of tumor cells and the release of cellular components in the circulation, resulting in electrolytes and metabolic disturbances that can lead to organ dysfunction and even death.

1. Introduction

2. Definition and Classification

| Cairo–Bishop Definition of Tumor Lysis Syndrome | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory TLS = modification of at least 2 parameters within 24 h |

|

Or 25% increase | within 3 to 7 days after chemotherapy initiation |

|

Or 25% decrease | ||

| Clinical TLS = laboratory TLS + 1 organ dysfunction or death |

|

||

-

changes of the laboratory parameters must be simultaneous within 24 h because the patient may develop one abnormality, and later on another, unrelated to TLS (e.g., hypocalcemia associated with sepsis);

-

symptomatic hypocalcemia has to be a criterion for clinical TLS, even when the decrease in calcium level is less than 25% of baseline;

-

a 25% variation of a parameter is significant for the diagnosis only if it causes symptoms or if the value is not within the normal range [2].

3. Pathogenesis

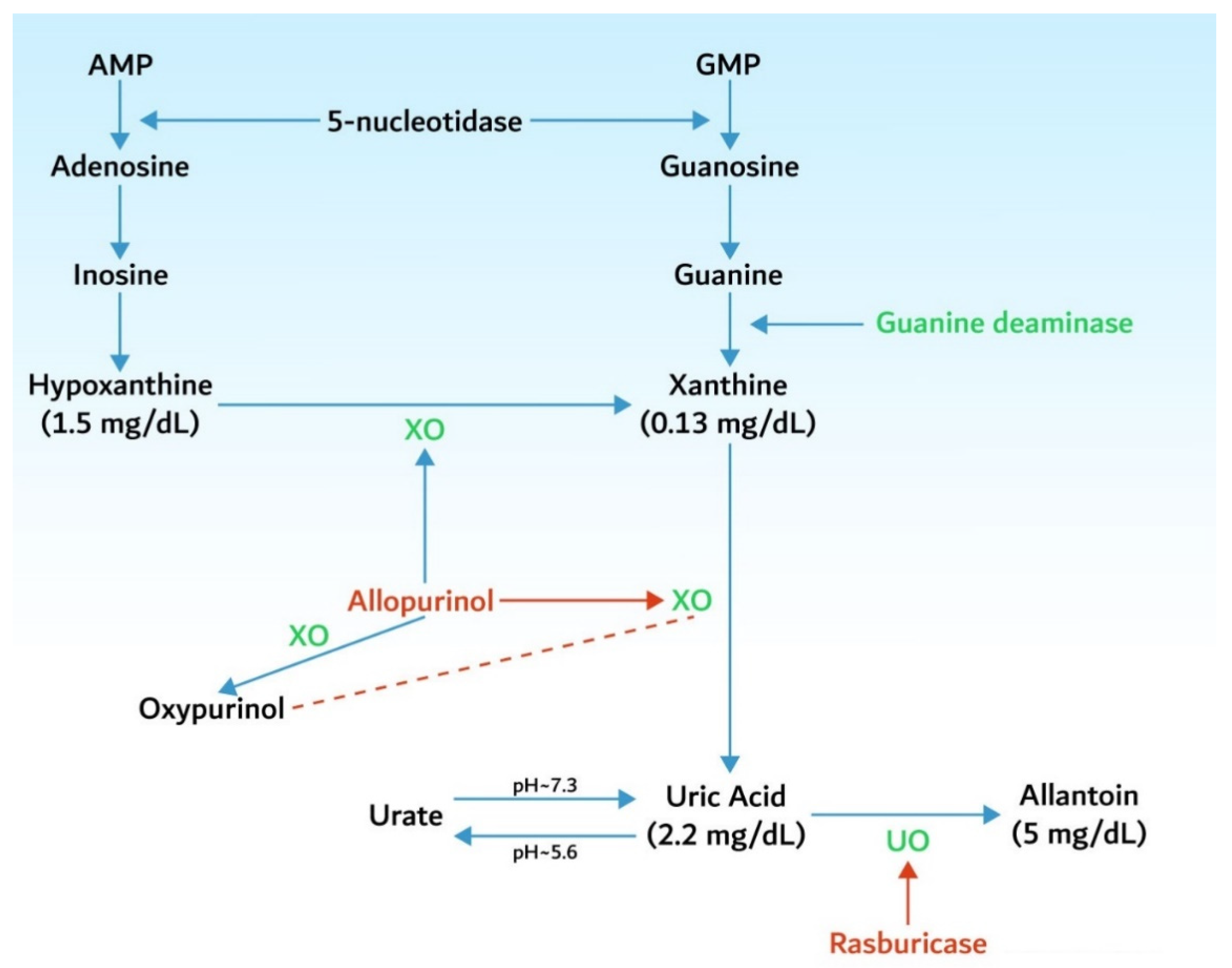

3.1. Hyperuricemia

3.2. Hyperkalemia

3.3. Hyperphosphatemia and Hypocalcemia

4. Epidemiology

| Germ cell tumors |

| Neuro- and medulla blastomas |

| Small cell carcinoma and other lung tumors |

| Breast, ovarian, and vulvar neoplasms |

| Hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Colorectal and gastric carcinoma |

| Melanoma |

| Sarcoma |

5. Identification of Patients at Risk

| Tumor Risk Factors | Patient-Related Risk Factors |

|---|---|

| Type of tumor | Male gender |

| Tumor volume (tumors > 10 cm) | Age > 65 years |

| Metastatic disease | Pretreatment serum creatinine > 1.4 mg/dL |

| Tumor growth rate (LDH > 2 times NV) | Renal obstruction |

| Level of leukocytosis (>25,000/mm3) | Pretreatment serum uric acid > 7.5 mg/dL |

| Sensitivity to chemotherapy (germ cell tumors, small cell lung cancer, etc.) | Associated conditions (hypotension, hypovolemia, nephrotoxic drugs, CKD) |

6. Tumor Lysis Syndrome Management

6.1. Prophylaxis

-

every 4 to 6 h after antitumor therapy initiation for patients at high risk;

-

every 8 to 12 h for patients at intermediate risk;

-

daily for patients at low risk.

-

to avoid the nephrotoxic drugs (NSAIDs, contrast agents);

-

to stop the treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers.

6.2. Treatment

Renal Replacement Therapy

-

daily hemodialysis;

-

continuous veno-venous hemofiltration;

-

combination of intermittent hemodialysis and continuous hemofiltration/hemodiafiltration for an efficient clearance of phosphate, which is time dependent. These techniques use dialysis membranes with large pores, which allow for rapid clearance of molecules that otherwise are not efficiently removed by conventional hemodialysis.

References

- Rastegar, M.; Kitchlu, A.; Shirali, A.C. Tumor Lysis Syndrome. In Onco-Nephrology; Finkel, K.M., Perazella, M.A., Cohen, E.P., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 275–280.e3.

- Howard, S.C.; Jones, D.P.; Pui, C.-H. The Tumor Lysis Syndrome. N. Eng. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1844–1854.

- Abu-Alfa, A.K.; Younes, A. Tumor Lysis Syndrome and Acute Kidney Injury: Evaluation, Prevention, and Management. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2010, 55, S1–S13.

- Matuszkiewicz-Rowinska, J.; Malyszko, J. Prevention and Treatment of Tumor Lysis Syndrome in the Era of Onco-Nephrology Progress. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2020, 45, 645–660.

- Montesinos, P.; Lorenzo, I.; Martin, G.; Sanz, J.; Perez-Sirvent, M.L.; Martinez, D.; Orti, G.; Algarra, L.; Martinez, J.; Moscardo, F.; et al. Tumor Lysis Syndrome in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Identification of Risk Factors and Development of a Predictive Model. Haematologica 2008, 93, 67–74.

- Wilson, F.P.; Berns, J.S. Onco-Nephrology: Tumor Lysis Syndrome. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 1730–1739.

- McDonnell, C.; Barlow, R.; Campisi, P.; Grant, R.; Malkin, D. Fatal Peri-Operative Acute Tumour Lysis Syndrome Precipitated by Dexamethasone. Anaesthesia 2008, 63, 652–655.

- Furtado, M.; Simon, R. Bortezomib-Associated Tumor Lysis Syndrome in Multiple Myeloma. Leuk. Lymphoma 2008, 49, 2380–2382.

- Lipstein, M.; O’Connor, O.; Montanari, F.; Paoluzzi, L.; Bongero, D.; Bhagat, G. Bortezomib-Induced Tumor Lysis Syndrome in a Patient with HIV-Negative Plasmablastic Lymphoma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2010, 10, E43–E46.

- Fuente, N.; Mañe, J.M.; Barcelo, R.; Muñoz, A.; Perez-Hoyos, T.; Lopez-Vivanco, G. Tumor Lysis Syndrome in a Multiple Myeloma Treated with Thalidomide. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 537.

- Lee, C.-C.; Wu, Y.-H.; Chung, S.-H.; Chen, W.-J. Acute Tumor Lysis Syndrome after Thalidomide Therapy in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Oncologist 2006, 11, 87–88.

- Francescone, S.A.; Murphy, B.; Fallon, J.T.; Hammond, K.; Pinney, S. Tumor Lysis Syndrome Occurring after the Administration of Rituximab for Posttransplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder. Transplant. Proc. 2009, 41, 1946–1948.

- Noh, G.Y.; Choe, D.H.; Kim, C.H.; Lee, J.C. Fatal Tumor Lysis Syndrome during Radiotherapy for Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 6005–6006.

- Fleming, D.R.; Henslee-Downey, P.J.; Coffey, C. Radiation Induced Acute Tumor Lysis Syndrome in the Bone Marrow Transplant Setting. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1991, 8, 235–236.

- Al-Kali, A.; Farooq, S.; Tfayli, A. Tumor Lysis Syndrome after Starting Treatment with Gleevec in a Patient with Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2009, 34, 607–610.

- Hsieh, P.-M.; Hung, K.-C.; Chen, Y.-S. Tumor Lysis Syndrome after Transarterial Chemoembolization of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Case Reports and Literature Review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 4726.

- Simmons, E.D.; Somberg, K.A. Acute Tumor Lysis Syndrome after Intrathecal Methotrexate Administration. Cancer 1991, 67, 2062–2065.

- Hande, K.R.; Garrow, G.C. Acute Tumor Lysis Syndrome in Patients with High-Grade Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Am. J. Med. 1993, 94, 133–139.

- Cairo, M.S.; Bishop, M. Tumour Lysis Syndrome: New Therapeutic Strategies and Classification. Br. J. Haematol. 2004, 127, 3–11.

- Mehta, R.L.; Kellum, J.A.; Shah, S.V.; Molitoris, B.A.; Ronco, C.; Warnock, D.G.; Levin, A. Acute Kidney Injury Network: Report of an Initiative to Improve Outcomes in Acute Kidney Injury. Crit. Care 2007, 11, R31.

- Shimada, M.; Johnson, R.J.; May, W.S.; Lingegowda, V.; Sood, P.; Nakagawa, T.; Van, Q.C.; Dass, B.; Ejaz, A.A. A Novel Role for Uric Acid in Acute Kidney Injury Associated with Tumour Lysis Syndrome. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 2960–2964.

- Cirillo, P.; Gersch, M.S.; Mu, W.; Scherer, P.M.; Kim, K.M.; Gesualdo, L.; Henderson, G.N.; Johnson, R.J.; Sautin, Y.Y. Ketohexokinase-Dependent Metabolism of Fructose Induces Proinflammatory Mediators in Proximal Tubular Cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 545–553.

- Han, H.J.; Lim, M.J.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, J.H.; Yang, I.S.; Taub, M. Uric Acid Inhibits Renal Proximal Tubule Cell Proliferation via at Least Two Signaling Pathways Involving PKC, MAPK, CPLA2, and NF-ΚB. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2007, 292, F373–F381.

- Larson, R.A.; Pui, C.-H. Tumor Lysis Syndrome: Definition, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Etiology and Risk Factors. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/tumor-lysis-syndrome-definition-pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-etiology-and-risk-factors (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Dunlay, R.W.; Camp, M.A.; Allon, M.; Fanti, P.; Malluche, H.H.; Llach, F. Calcitriol in Prolonged Hypocalcemia Due to the Tumor Lysis Syndrome. Ann. Intern. Med. 1989, 110, 162.

- Andronesi, A.G.; Tanase, A.D.; Sorohan, B.M.; Craciun, O.G.; Stefan, L.; Varady, Z.; Lipan, L.; Obrisca, B.; Truica, A.; Ismail, G. Incidence and Risk Factors for Acute Kidney Injury Following Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation for Multiple Myeloma. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 3278–3285.

- Baeksgaard, L.; Sørensen, J.B. Acute Tumor Lysis Syndrome in Solid Tumors—a Case Report and Review of the Literature. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2003, 51, 187–192.

- Cairo, M.S.; Coiffier, B.; Reiter, A.; Younes, A. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Risk and Prophylaxis of Tumour Lysis Syndrome (TLS) in Adults and Children with Malignant Diseases: An Expert TLS Panel Consensus. Br. J. Haematol. 2010, 149, 578–586.

- Coiffier, B.; Altman, A.; Pui, C.-H.; Younes, A.; Cairo, M.S. Guidelines for the Management of Pediatric and Adult Tumor Lysis Syndrome: An Evidence-Based Review. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 2767–2778.

- Annemans, L.; Moeremans, K.; Lamotte, M.; Garcia Conde, J.; van den Berg, H.; Myint, H.; Pieters, R.; Uyttebroeck, A. Incidence, Medical Resource Utilisation and Costs of Hyperuricemia and Tumour Lysis Syndrome in Patients with Acute Leukaemia and Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in Four European Countries. Leuk. Lymphoma 2003, 44, 77–83.

- Wössmann, W.; Schrappe, M.; Meyer, U.; Zimmermann, M.; Reiter, A. Incidence of Tumor Lysis Syndrome in Children with Advanced Stage Burkitt’s Lymphoma/Leukemia before and after Introduction of Prophylactic Use of Urate Oxidase. Ann. Hematol. 2003, 82, 160–165.

- Mato, A.R.; Riccio, B.E.; Qin, L.; Heitjan, D.F.; Carroll, M.; Loren, A.; Porter, D.L.; Perl, A.; Stadtmauer, E.; Tsai, D.; et al. A Predictive Model for the Detection of Tumor Lysis Syndrome during AML Induction Therapy. Leuk. Lymphoma 2006, 47, 877–883.

- Truong, T.; Beyene, J.; Hitzler, J.; Abla, O.; Maloney, A.; Weitzman, S.; Sung, L. Features of Presentation Predict Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia at Low Risc for Tumor Lysis Syndrome. Cancer 2007, 110, 1832–1839.

- Jones, G.L.; Will, A.; Jackson, G.H.; Webb, N.J.A.; Rule, S. Guidelines for the Management of Tumour Lysis Syndrome in Adults and Children with Haematological Malignancies on Behalf of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 169, 661–671.

- Browning, L.A.; Kruse, J.A. Hemolysis and Methemoglobinemia Secondary to Rasburicase Administration. Ann. Pharmacother. 2005, 39, 1932–1935.