Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Uma Shankar Singh | -- | 4597 | 2022-07-27 11:16:02 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | + 54 word(s) | 4651 | 2022-07-28 03:47:12 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Singh, U.S.; Rutkowska, M.; Bartoszczuk, P. Renewable Energy Decision Criteria on Green Consumer Values. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25575 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Singh US, Rutkowska M, Bartoszczuk P. Renewable Energy Decision Criteria on Green Consumer Values. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25575. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Singh, Uma Shankar, Małgorzata Rutkowska, Paweł Bartoszczuk. "Renewable Energy Decision Criteria on Green Consumer Values" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25575 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Singh, U.S., Rutkowska, M., & Bartoszczuk, P. (2022, July 27). Renewable Energy Decision Criteria on Green Consumer Values. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25575

Singh, Uma Shankar, et al. "Renewable Energy Decision Criteria on Green Consumer Values." Encyclopedia. Web. 27 July, 2022.

Copy Citation

Renewable energy consumption is the call by United Nation Sustainable Development Goals, and sustainable consumption is the only solution for the future. An awareness towards the environment for the sustainable development is reaching implementation at various levels through channels with government promotions. RESs are accepted on a global scale, with common consensus being the requirement for future generations. The current generation is more aware and equipped with technological advancements, which can reach the vision of sustainability.

renewable energy

decision criteria

environment policy

green consumer values

sustainable development

solar

wind

hydro

geothermal

biomass

1. Introduction

Since the existence of life, energy has been the most important requirement for the survival and continuation of life. Science says that energy can neither be created nor be destroyed, but only its forms can be changed. Early life was dependent upon natural energy sources such as solar, water, and wind for all their energy needs [1]. With the changing time and the development of human life, fossil fuels were explored. The developing human life kept exploring different sources and means of energy generation. The 21st century is witnessing many transformations across industries. Energy demand for fuel is increasing, and to keep up the production, maintain quality, and satisfy consumers, it needs to be produced on a sustainable philosophy [2]. However, philosophical changes alone are not enough; only real implementations can bring a difference.

The energy sector is also in transition from nonrenewable to renewable energy sources (RESs). One way is that we are increasing our dependency on energy requirements, and another way is looking for environmentally sustainable energy sources [3]. Now, more emphasis is on the concept related to renewable energy production and promoting green consumption. However, the concept of renewable energy consumption is not new, as the beginning of the human life was purely dependent upon RESs for fulfilling their requirements [4]. The changing time is the indicator of researchers' dependence and continuous effort to find different ways for RES utility. Somehow, there are some successful milestones created, which is a motivator for continuation in the effort for growth with renewable energy sources at the industrial level, where there is mass consumption and major contribution to the energy consumption [1].

In reality, a complete switchover from nonrenewable energy sources to renewable energy sources is challenging because of several reasons. However, the push from the government to promote the RESs is contributing significantly to the green energy adoption. The global voice and steps offering benefits to aligning with world environment policies are also making a lucrative proposition for producers and consumers [5]. RESs are accepted because of continuous generation or the possibility to convert them back to nature. Fossil fuels are non-reversible and produce a higher level of pollution. Not only this, but the fossil fuels are nonrenewable and once they are gone, it will be difficult for the world to fulfill their energy requirements [6]. There is an urgent call for alternative solutions, where RESs are good substitutes and a sustainable step towards the energy sector.

An awareness towards the environment for the sustainable development is reaching implementation at various levels through channels with government promotions [7]. RESs are accepted on a global scale, with common consensus being the requirement for future generations. The current generation is more aware and equipped with technological advancements, which can reach the vision of sustainability [8]. The development in the implementation of green energy production and consumption is in the process of implementation, which requires speed in the implementation movement. Global awareness and activities aligned with the United Nation’s (UN) sustainable development goals [9] are also a supportive move to practical implementation of the green vision for a sustainable future, which is receiving considerate support from all nations around the globe.

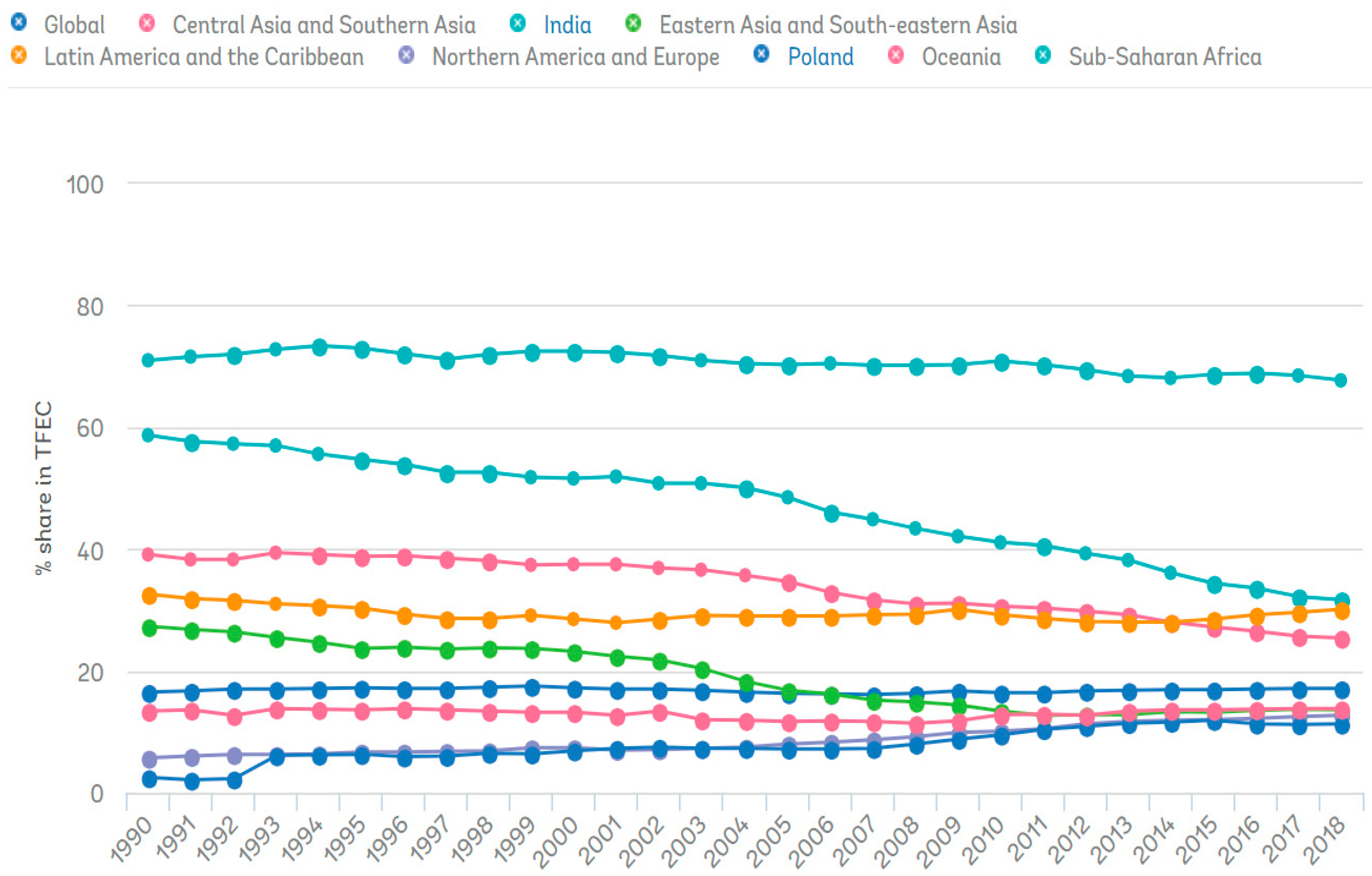

The main sources of renewable energy are solar, wind, hydro, geothermal and biomass [10]. The main reason of promotion of these energy sources is comparatively lesser harm to the environment and they are reversible [5]. Though the industrial requirements of energy are difficult to meet with the RESs, the domestic demands can be served. There are different schemes implemented on industrial levels as well as to the individual consumers for energy generation. Though the current situation shows the increase in contribution in most countries, some are on a straight line, while some countries have lost their path and have shown a decreased production of renewable energy over the years [11]. The natural phenomena and changes in environmental condition cannot be ignored, which may be an uncontrollable reason for an increase or decrease in production (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Renewable Energy Share in Total Final Energy Consumption 1990–2018 [11].

The target to increase the production capacity has become more important in 2022, because of the crisis in Ukraine creating a situation of uncertainty for the energy sector [12]. The demand is increasing with the increasing population. Most countries are implementing self-reliant energy generation, where renewable energy generation can be a support engine [5]. The sustainability of the world needs everybody’s contribution with a determined approach based on their capacity being either on the production side or the consumption side [13]. The fact is that the destruction of the environment and the greed to reach success has lad life to be in danger. The sustainable development goals are in the process of being reached, where countries are actively participating to be successful [14]. The UN sustainable development goal 7 is ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy to each and every individual all around the world [9][15]. The share of renewable energy in the total final energy trend (Figure 1) year on year is showing a clear map [11], which can be a criteria to measure the requirement for structural changes to support the renewable energy production and consumption.

Consumer acceptance or rejection of any product or service is the determinant of the future of that specific offering [16]. It is very important to understand the consumer views on the green offerings. The consumption process is a complex situation where an individual thinks of other alternatives and compares offerings in various categories. Nevertheless, consumers of the 21st century are more aware and concerned about the environment and a sustainable future for coming generations [17]. However, the consumption decision for green energy offerings is not only the subject of awareness for sustainability, rather many other factors based on their consumption values [18]. Green consumer values are the shaped behavior of an individual based on their understanding about environmentally friendly offerings [19]. In the case of RES, the green consumer values are one of the deciding factors for consumers’ preference to choose a specific renewable energy based on their perception and preferences.

The green consumer values are driven by six parameters measuring an individual view on the consumption of energy from RESs [16][19]. The six parameters are: CRITERIA 1—It is important to me that the energy I use does not harm the environment; CRITERIA 2—I consider the potential environmental impact of my actions when making energy usage decisions; CRITERIA 3—My energy consumption habits are affected by my concern for our environment; CRITERIA 4—I am concerned about wasting the resources of our planet when I use energy; CRITERIA 5—I would describe myself as environmentally responsible using energy; CRITERIA 6—I am willing to be inconvenienced in order to accept energy that is more environmentally friendly. Mostly, these are the decision criteria for an individual for the selection of any specific RES for their energy consumption [16][19]. The options of RESs are solar, wind, hydro, geothermal and biomass, considerable in the majority of cases, though there may also be some other sources that are not as big contributors as the presented six sources.

To date, many studies have been conducted on RESs for sustainable life, and researchers are continually exploring different aspects of such energy contributions [10][20]. The research is based on the core concept of sustainability and the requirements of solar, wind, hydro, geothermal and biomass as RESs. However, another component of green consumer values must be considered to justify the demand- or consumer-side opinions [21][22]. However, another study in the same area was conducted to understand the green consumer values concept with respect to RESs. Here, the research is differentiated by observing the research problem that there is a requirement to categorize the green consumer value parameters in a hierarchy of importance for selection by consumers for these specific five RESs and their alignment with environment policy based on a comparison of Poland and India as strategic countries of Europe and Asia, respectively, which is necessary to support the UN sustainable development goal.

2. Environmental Policy

Environmental policy means any measure taken by a public or private organization or by a government concerning the impact of human activities on the environment. Primarily, these are measures aimed at preventing or reducing the harmful effects of human activities on ecosystems [2]. Thus, “environmental policy may include regulations and rules on water and air pollution, chemical and oil spills, smog, drinking water quality, land conservation and management, and wildlife protection such as the protection of endangered species”. Environmental management systems, preservation, and natural resource management were formerly the responsibility of the national sector officials. Recently, climate awareness and management have been framed as a larger enterprise that necessitates the active participation of communities, people, non-governmental groups, and the business sector [23]. As a result, there is a growing trend with regard to environmental conservation and preservation in the interest of the public to be delegated widely [24].

Furthermore, as customers, private landowners, and policy debate members, people and democratic institutions have a larger influence on the ecosystem. Developments in the government’s involvement in environmental policy have occurred in reaction to social, economic, and technical changes that countries have experienced during the last several decades [7]. This movement comprises a transition from a vision of governance defined by the nation-state to one that acknowledges the contributions of many levels of authority (global, multinational), as well as the responsibilities of the private industry, nonprofit actors, and society organizations [25]. The complexities, ambiguity, and urgency of many global and local environmental challenges have prompted numerous questions about the validity of the classic model of development and the interaction between society, commerce, and ecosystem [26]. It has also generated concerns about the local governmental model’s capacity to satisfy the needs of economic management in a responsible way.

As a result, attention for sustainable development has shifted upwards to international institutions and multinational corporations, and downwards to local authorities, enterprises, and resources users [27]. PEP2030 is a justification and successful implementation of the SRD provisions within a strategic documentation system. As a result, the core purpose of PEP2030, namely the development of the environment’s potential for the benefit of residents and enterprises, was directly transferred from the SOR. Specific aims of PEP2030 have been defined in response towards the most important environmental trends highlighted in the diagnostic, in such a way that it allows for the harmonization of environmental regulation with economic and social demands [28].

2.1. Europe Adaptation of Environment Policy

EU nations have established objectives that will guide European environmental policy until 2020, as well as a roadmap for continued growth until 2050. Furthermore, funding has been identified for specific research programs, regulations, and investment to safeguard, maintain, and enhance the EU’s ecological integrity, and reshape the EU into a source of green energy, being a competitive and affordable economy as well as a safeguard to EU members from negative impacts on the environment [23]. Despite the fact that several environmental organizations are making efforts to promote green projects, they are disorganized and divided, and political parties have paid minimal attention to environmental difficulties, while the public consciousness has switched to the core economic matters of everyday living.

Up to this point, achievements have been impressive, but only partially, as a result of government decisions, industry slowdown and restructuring having all had a significant influence on reducing pollution [29]. Unsatisfactory outcomes in Poland as a minimally environmentally committed EU member country influenced Polish preferences for revised EU green initiatives. Existing EU policies, their alignment with Poland’s energy objectives, and a shift in expectation of future EU policies account for a large portion of the fluctuation in opinions. Second, Poland’s policy response had a considerable impact on the EU 2030 climate action agenda [23].

Responding to the anticipated limitations in the Polish electricity industry, decision makers did not support European climate change policy [29]. Climate change policy in Poland following the change in the 1990s may be described as centrally managed and technologically implemented [30]. Gas imports from Russia, as well as their dispersion owing to the political environment, have long overshadowed Polish energy security concerns. This may seem remarkable, given that gas contributed only 13 percent of total primary energy supply in 2009, with a third generated internally. More than 80% of gas was imported from Russia, which many analysts and politicians saw as the main danger to Polish energy security as a result of political actions [31].

2.2. Poland—A View towards Environmental Policy

It is sometimes stated that over the previous two decades, Polish environmental policy has moved in the opposite direction of the major advancements in EU nations. Whilst the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and enhancement of renewable energy were significant in the outline of Polish protection of the environment, by the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first, the government began to perceive European climate policy as a threat to the Polish economy [23]. Following the launch of the ‘Energy and Climate Package’ in 2008, the Polish authorities implemented a “pre-emptive veto” policy that stymied future progress. Polish energy is dominated by coal, the majority of which comes from domestic sources. In 2013, it accounted for 54% of the energy industry and 88% of the power sector [30].

To differentiate the power mix, the government plans to build a nuclear power plant. Meanwhile, closures of unprofitable mines meet stark sectorial resistance. The government of Poland in 2019 adopted the National Environmental Policy 2030 (PEP2030). Since then, PEP2030 has become the most important strategic document in the sphere of environment and water management in Poland [29]. This document was, in the system of strategic documents, a specification of the medium-term Strategy for Responsible Development until 2020 with an outlook until 2030. The task of PEP2030 is to ensure Poland’s ecological security and high quality of life for all inhabitants. Furthermore, PEP2030 supports the worldwide execution of Poland’s objectives and obligations, along with the EU and the UN, particularly in the framework of the EU’s energy and climate change policy objectives till 2030 and the 2030 Agenda For Sustainable Development (SDGs) included in Agenda 2030 [1].

In 2019, the Council of Ministers in Poland adopted an important strategic document: the 2030 National Environmental Policy (PEP2030). The role of PEP2030 is to ensure Poland’s ecological safety and high quality of life for all residents. State National Policy until 2030 (PEP2030) is a strategy in accordance with the act on the principles of development policy (SOR). In the strategic model, it specifies and operationalizes the “Strategy for Sustainable Development until 2020” with a perspective until 2030, which is valid for the years 2023-2027. Supporting the achievement of the 2030 goals [32], PEP2030 repeals the Strategy “Energy Security and Environment—a perspective until 2020” in the part concerning Objective 1: Sustainable management of environmental resources and Objective 3: Improvement of the environment.

2.3. Asia Adaptation of Environment Policy

Climate change has been a major challenge for countries in Asia. There is considerable talk around the rebuilding of the climate and to be resilient to disasters. Tackling climate change and enhancing the environmental sustainability is the major concern [32]. The Asian Development Bank has set its strategy until 2030. The main theme of the strategy is to keep committed and ensure the support for climate change mitigation and adoption activities by 2030, though there were challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic that were hurdles for the global development. Still, countries have the most possible initiatives for the adoption of environment policy. The Asia climate change adaptation forum met in 2021 under the theme of enabling resilience for all with scaling up the action programs and sharing their learning for the climate resilient developments [33].

The main agenda of this meeting established addressing resilience by inclusivity of all, resilience for nature by each individual, being resilient towards the economic sector, and resilience for local areas and communities. Asia is witnessing environmental change, which is impacting living organisms [24]. The growth-led countries in Asia are polluting their air and water bodies, which is a serious concern that needs to be addressed without delay. Asia is committed to the adoption of environmental policy for sustainable development. Asia is constituted of a mix of developed and developing economies, which has brought the continent to the crossroads of environmental sustainability. These countries have a large variation in their economic, political, and social developments.

The countries Japan and Singapore are more focused on efficient energy production and consumption, as well as the protection of ecosystems. However, at the same time, the countries China and India are more focused on policy making for sustainable growth. However, in all cases, the concern is energy security for each and every individual all around the world [34]. There is a requirement of close observation for the framing of environmental policy because a varied participation brings a deviated approach among stakeholders to tackle ecological challenges. However, the emergence of India and China as leading economies in Asia has made the world assume that the current century is the century of Asia, though it is evident that the environment footprint generated by the economic developments are essential to policy framing. At the same time there is a question: Is this development of Asia environmentally sustainable?

2.4. India—A View towards Environmental Policy

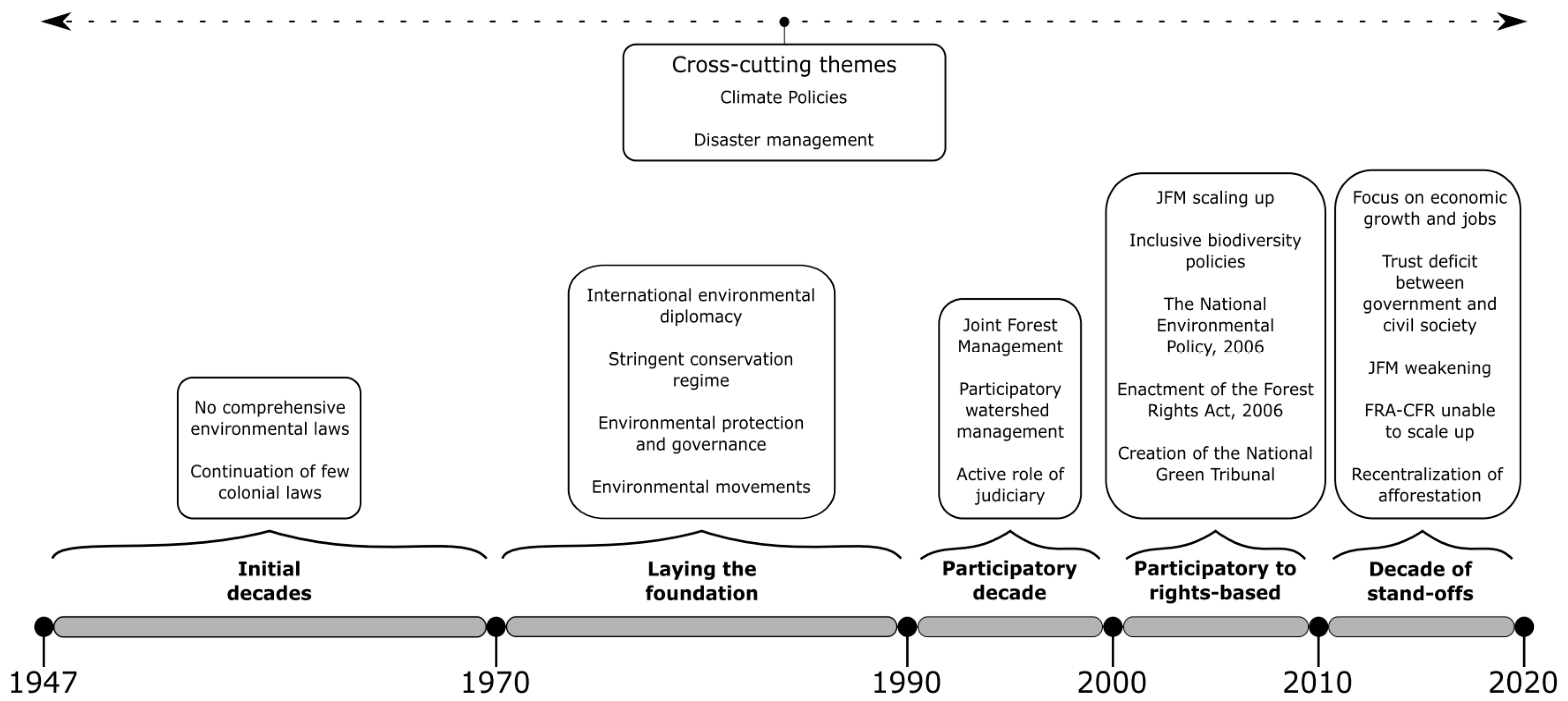

Environmental policy is the core of India for its vision to exceed on the path of a sustainable economy. India took pledges in 2021 for keeping climate change at the center of environmental policy structure under the commitments of the Paris Agreement. The pledge to have zero carbon emissions by 2070 and the production of 500 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity by 2030 is leading India in its environment policy [35]. There are several steps taken by the government of India for sustainable development following environmental policy. The evolution of environmental policy in India began with its independence in 1947 and is positively moving forward every year [33].

The first in this series is ‘Paris Agreement Ratification’, providing a framework for the immediate action all around the world on the issue of climate change. The second is the ‘Clean Development Mechanism’, aiming to optimize Indian industries on the factors of efficiency, energy, fuel transition, solid waste management, etc., to reduce the pressure on the environment. The third is the ‘State Lead Action Plans on Climate Change’ to create organizations that can be capable of promoting activities and addressing issues in climate change. The fourth is the ‘National Clean Energy Fund’, which is the initiative of the government of India of imposing carbon tax over coal and promoting clean energy. The fifth and last is the ‘National Adaptation Fund for Climate Change’ means of financial support at the state and national level to support the solution to tackle climate change.

The policy-making activities in India are controlled by government authorities. The environmental policy framing has been conducted through a multilateral approach based on historic incidents at the national and international levels. Since gaining independence, the environmental issues were also incorporated into economic development. Later, during the 1980s, the policy framework pushed to align with international standards, which transformed the structure and vision for environment policy (Figure 2) [33]. In the later years, during the 1990s, the approaches shifted to participative and collaborative tools to solve the environmental issues among global communities. The current decade is the era of global uniformity to be univocal for the activism including the judiciary and civil society implementing scientific approaches to cater to environment issues [35].

Figure 2. Evolution of India’s environmental policy [33].

3. Sustainable Development

There are a great many definitions of sustainable development (SD) in the literature. The idea of sustainable development originated in the early 1960s. It was a report presented to the session of the General Assembly on 26 May 1969 by U Thant, Secretary-General of the United Nations, entitled the problems of human environment expressed in resolution 2398, which stated that “for the first time in the history of mankind there was a worldwide crisis caused by the destruction of the natural environment, he documented this thesis with alarming statistical data and called for a planned international action to save the environment” [36].

The idea seems to have achieved wide interest-based attention that other development concepts lack, and emerges prepared to remain the ubiquitous development paradigm for the future [37][38][39]. Despite its ubiquity and acceptance, disillusionment with the phrase is common, as scholars continue to pose concerns regarding its meaning or description, as well as what it includes and suggests for developing principles and application, with no clear solutions appearing [34][38][40][41][42].

As a result, SD risks becoming a truism, similar to suitable technology—a trendy and rhetorical word to which everyone pays tribute but no one appears to be able to explain precisely [34][35]. The environmental economist Jack Pezzey identified, in the late 1980s, more than 60 definitions of SD (Pezzey 1989) [43], while Michael Jacobs in the following decade established as many as 386 definitions (Jacobs 1995), and already in the 21st century Barbara Carroll has pointed to the operation of more than 500 (Carroll 2002). Lithuanian researchers, on the other hand, found that there are about 100 definitions in the economic literature alone (Ciegis et al. 2009). However, those without undertaking a deeper analysis are presented as the most important ones.

The Club of Rome, 1972, and then the Brundtland Report, 1987, by Gro Harlem Brundtland (WCED) (UN) (1987) says “Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. Conway, 1987: 96 says “The net productivity of biomass (positive mass balance per unit area per unit time) maintained over decades to centuries”. Turner, 1988: 12 says “In principle, such an optimal (sustainable growth) policy would seek to maintain an “acceptable” rate of growth in per-capita real incomes without depleting the national capital asset stock or the natural environmental asset stock”. Rio Declaration, 1992 said “The rearrangement of technological, scientific, environmental, economic and social resources in such a way that the resulting heterogeneous system can be maintained in a state of temporal and spatial equilibrium”.

Sustainable development is defined as the type of human development that fulfills the necessities of the actual generation without impairing the possibilities for the next generations to meet their necessities [44]. According to Sen, 1999, a sustainable society is one in which the individual ability to do what they have good reason to value is continually enhanced. Another study by Johannesburg, 2002 says that sustainable development means the integration of social, economic and environmental factors into planning, implementation and decision making so as to ensure that development serves present and future generations. Stappen, 2006 defines sustainable development as a development that meets the basic needs of all human beings, which conserves, protects and restores the health and integrity of the ecosystem, without compromising the future generations’ ability to meet their own needs.

As can be understood based on the literature explained above, the concept of SD is ambiguous. All definitions indicate that SD is a process related to economic activity. Various definitions of ecological policy exist in the literature to date. For the purpose of this entry, it has been agreed that the ecological policy is a conscious and purposeful activity of the state, local self-governments and economic entities in the field of environmental management, i.e., protection of ecosystems or selected elements of the biosphere, shaping of ecosystems or selected elements of the biosphere, and management of the environment, i.e., the use of its resources and values [45]. The subject of the ecological policy is therefore the natural environment and its condition assessed from the point of view of human biological, social and economic needs. One of the principles of ecological policy is the principle of sustainable development [46]. It should be noted that the essence of the sustainable development is equal treatment of social, economic and ecological reasons, which means the necessity of integrating the environmental protection issues with the general state policy [47].

4. Green Consumer Values

The concept of green consumer values is the main focus of production companies. They know if the consumer will not accept the product and service offerings, then the viability of the business will be in question. The sustainable offerings are the requirement for the current time. Consumers are looking for products and brands advocating the sustainability in their offerings. The demands are so much higher that many brands have claimed the growth in their offerings of green values twice as high compared to traditional offerings by their competitors [48]. However, at the same time many counter problems are a hurdle for the green offerings, such as the price for the offering. The consumer awareness about the sustainable consumption to save the planet is the major enforcement to transform consumers for their consumption values. There are initiatives by government and non-government organizations everywhere to support the green consumption by awareness creation and providing factors of sustainable production. Manufacturing companies are also motivated to be participative in these activities with their commitment to the environment and a sustainable planet [49].

Collaborative activity by all stakeholders can make green consumption for a sustainable future. Research all around the world has been promoting sustainable consumption for many years. There is sufficient experimental research in economics, marketing, and psychology, measuring the consumer behavior towards green offerings [22]. The result of this research has given learning to academicians about consumer preferences on green consumption. Policy has come up as the intervention in many studies where the findings are mostly focused on consumer behavior towards sustainable purchasing [48]. Companies are advised to apply activities to use social influence following actions of using social media, shaping habits for green consumption, leveraging sustainable consumption, thinking over the decision from the heart or the brain, and the favoring experiences. Sustainable business has the sufficient momentum to go ahead, but still brands are required to create a relevance that may be justifiable to the green consumer values [19].

Behavioral science may help companies to realize their value among consumers and to understand consumer and target market demand for offerings. There are many drivers pushing green consumption shaping consumers’ green values, including behavioral factors, product- and producer-related factors, personal capabilities, context, socio-demographic variables, interpersonal environment values, and intrapersonal non-environment values [50]. The environmental protection and the concern of sustainable consumption depends upon human behavior and the consumer’s lifestyle [21]. Studies have witnessed that consumers concerned about the environment prefer to consume green products. However, consumer preferences keep swinging and switching from ecofriendly green products to traditional products and vice versa. The reason behind these swings and switching over is the lack in consistent appeal from green products to keep hold of customers with emotions. The consumer reluctance to switch over is called the green gap [51]. This gap is the reflection of customer denial on green consumption, though they are favoring the environment and are concerned about the planet sustainability.

Further, this may lead to the problem that demand for green products will drag companies to instability [45]. The green gap has been seen from different perspectives, such as social desirability bias, limited availability of green products, lack of marketing messages, higher price perception, lack of quality, and high effort in purchasing. Above everything, the most important factor in the green consumption is observed to be the consumer’s consumption values [22]. Consumers have been attracted to adopting environmentally sustainable lifestyles, which has been increasing over the last few years. Modern consumers are not ready to compromise with the future and they are very conscious with their consumption habits. This is leading to buzzwords such as green consumers and green products [21]. So, the companies are unfolding the new realms of production by understanding the green consumer values and buyer behavior for green products and services. Though the importance of consumer values is known to companies, still the challenge in the consumer behavior is implicit criteria of fluctuating evaluations. Green marketing activities can be a tool for companies to respond consumers’ green values [52].

References

- Brodny, J.; Tutak, M.; Saki, S.A. Forecasting the Structure of Energy Production from Renewable Energy Sources and Biofuels in Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 2539.

- Carballo-Penela, A.; Castromán-Diz, J.L. Environmental Policies for Sustainable Development: An Analysis of the Drivers of Proactive Environmental Strategies in the Service Sector: Environmental Policies for Sustainable Development. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015, 24, 802–818.

- Jałowiec, T.; Wojtaszek, H. Analysis of the RES Potential in Accordance with the Energy Policy of the European Union. Energies 2021, 14, 6030.

- Mamkhezri, J.; Thacher, J.A.; Chermak, J.M. Consumer Preferences for Solar Energy: A Choice Experiment Study. Energy J. 2020, 41.

- O’Shaughnessy, E.; Heeter, J.; Shah, C.; Koebrich, S. Corporate Acceleration of the Renewable Energy Transition and Implications for Electric Grids. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 146, 111160.

- Szaruga, E.; Kłos-Adamkiewicz, Z.; Gozdek, A.; Załoga, E. Linkages between Energy Delivery and Economic Growth from the Point of View of Sustainable Development and Seaports. Energies 2021, 14, 4255.

- Kulovesi, K.; Oberthür, S. Assessing the EU’s 2030 Climate and Energy Policy Framework: Incremental Change toward Radical Transformation? RECIEL 2020, 29, 151–166.

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.; Ramayah, T.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Sehnem, S.; Mani, V. Pathways towards Sustainability in Manufacturing Organizations: Empirical Evidence on the Role of Green Human Resource Management. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 212–228.

- Take Action for the Sustainable Development Goals—United Nations Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Owusu, P.A.; Asumadu-Sarkodie, S. A Review of Renewable Energy Sources, Sustainability Issues and Climate Change Mitigation. Cogent Eng. 2016, 3, 1167990.

- Trends|Tracking SDG 7. Available online: https://trackingsdg7.esmap.org/time?c=World+Central_Asia_and_Southern_Asia+Eastern_Asia_and_South-eastern_Asia+Latin_America_and_the_Caribbean+Northern_America_and_Europe+Oceania+Sub-Saharan_Africa+Western_Asia_and_Northern_Africa&p=Renewable_Energy&i=Renewable_Energy_share_in_Total_Final_Energy_Consumption_(%) (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- 2022—World Energy Transitions Outlook: 2022 1.5 °C Pathw.Pdf. Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/files/irena/agency/publication/2022/mar/irena_weto_summary_2022.pdf?la=en&hash=1da99d3c3334c84668f5caae029bd9a076c10079 (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Keidel, J.; Bican, P.M.; Riar, F.J. Influential Factors of Network Changes: Dynamic Network Ties and Sustainable Startup Embeddedness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6184.

- 2022 Initiative Foundation—Co-Creation & Acceleration to Reach the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.2022initiative.org/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- SDG Indicators. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/goal-07/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Bartoszczuk, P.; Singh, U.S.; Rutkowska, M. An Empirical Analysis of Renewable Energy Contributions Considering GREEN Consumer Values—A Case Study of Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 1027.

- Sachdeva, S.; Jordan, J.; Mazar, N. Green Consumerism: Moral Motivations to a Sustainable Future. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 6, 60–65.

- Pinto, D.C.; Nique, W.M.; Añaña, E.D.S.; Herter, M.M. Green Consumer Values: How Do Personal Values Influence Environmentally Responsible Water Consumption? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 122–131.

- Rutkowska, M.; Bartoszczuk, P.; Singh, U.S. Management of GREEN Consumer Values in Renewable Energy Sources and Eco Innovation in INDIA. Energies 2021, 14, 7061.

- Aboagye, B.; Gyamfi, S.; Ofosu, E.A.; Djordjevic, S. Status of Renewable Energy Resources for Electricity Supply in Ghana. Sci. Afr. 2021, 11, e00660.

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the World through GREEN-Tinted Glasses: Green Consumption Values and Responses to Environmentally Friendly Products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354.

- Bailey, A.A.; Mishra, A.; Tiamiyu, M.F. GREEN Consumption Values and Indian Consumers’ Response to Marketing Communications. JCM 2016, 33, 562–573.

- Millard, F. Environmental Policy in Poland. Environ. Politics 1998, 7, 145–161.

- Available online: https://www.local2030.org/library/421/Recommendations-to-integrate-the-SDGs-into-local-party-manifestos.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Skjærseth, J.B. Implementing EU Climate and Energy Policies in Poland: Policy Feedback and Reform. Environ. Politics 2018, 27, 498–518.

- Environmental Policy—An Overview|ScienceDirect Topics. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/environmental-policy (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Singh, U. Total Productive Maintenance a Tool for Efficient Production Management. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328841028_TOTAL_PRODUCTIVE_MAINTENANCE_A_TOOL_FOR_EFFICIENT_PRODUCTION_MANAGEMENT (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Singh, U.S. Cost Estimation Using Econometric Model for Restaurant Business. QME 2019, 20, 209–216.

- Ancygier, A. Poland and the European Climate Policy: An Uneasy Relationship. Kwart. Nauk. OAP UW E-Polit. 2013, 7, 76–93.

- Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/371685743/TZW-Sustainability-and-the-Waste-Hierarchy-2003 (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Singh, U.S. A Conceptual Approach Correlating Behavioral Neuroscience with Vertically Coordinated Vegetable Supply Chain. Sch. J. Arts Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2018, 6, 1021–1027.

- Szulecki, K.; Fischer, S.; Gullberg, A.T.; Sartor, O. Shaping the ‘Energy Union’: Between National Positions and Governance Innovation in EU Energy and Climate Policy. Clim. Policy 2016, 16, 548–567.

- Kryk, B.; Guzowska, M.K. Implementation of Climate/Energy Targets of the Europe 2020 Strategy by the EU Member States. Energies 2021, 14, 2711.

- Tolba, M.K. The Premises for Building a Sustainable Society—Address to the World Commission on Environment and Development; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 1984; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Ballal, A.; Tambe, S.; Joe, E.T. The Evolution of India’s Environmental Policy. Indian For. 2021, 147, 743.

- Mensah, J.; Enu-Kwesi, F. Implications of Environmental Sanitation Management for Sustainable Livelihoods in the Catchment Area of Benya Lagoon in Ghana. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2019, 16, 23–43.

- Raport U Thanta—Encyklopedia PWN—źródło wiarygodnej i rzetelnej wiedzy. Available online: https://encyklopedia.pwn.pl/haslo/Raport-U-Thanta;3966094.html (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Scopelliti, M.; Molinario, E.; Bonaiuto, F.; Bonnes, M.; Cicero, L.; De Dominicis, S.; Fornara, F.; Admiraal, J.; Beringer, A.; Dedeurwaerdere, T.; et al. What Makes You a ‘Hero’ for Nature? Socio-Psychological Profiling of Leaders Committed to Nature and Biodiversity Protection across Seven EU Countries. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 61, 970–993.

- Elliott, J.A. An Introduction to Sustainable Development, 4th ed.; Routledge Perspectives on Development; Routledge: London, UK; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-415-59072-3.

- Shepherd, E.; Milner-Gulland, E.J.; Knight, A.T.; Ling, M.A.; Darrah, S.; Soesbergen, A.; Burgess, N.D. Status and Trends in Global Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital: Assessing Progress Toward Aichi Biodiversity Target 14. Conserv. Lett. 2016, 9, 429–437.

- Montaldo, C.R.B. Sustainable Development Approaches for Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation & Community Capacity Building for Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation. 17. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/877LR%20Sustainable%20Development%20v2.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Lélé, S.M. Sustainable Development: A Critical Review. World Dev. 1991, 19, 607–621.

- Pezzey, J.C.V. Economic Analysis of Sustainable Growth and Sustainable Development; Environment Department Working Paper No. 15. Published as Sustainable Development Concepts: An Economic Analysis, World Bank Environment Paper No. 2; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1989.

- Shahzalal, M.; Hassan, A. Communicating Sustainability: Using Community Media to Influence Rural People’s Intention to Adopt Sustainable Behaviour. Sustainability 2019, 11, 812.

- United Nations. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime World Drug Report 2016; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-92-1-148286-7.

- Kasztelan, A. Green Growth, Green Economy and Sustainable Development: Terminological and Relational Discourse. Prague Econ. Pap. 2017, 26, 487–499.

- Proczek, R. Pojęcie zrównoważonego rozwoju. Available online: http://urbnews.pl/pojecie-zrownowazonego-rozwoju/ (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Zhang, X.; Dong, F. Why Do Consumers Make Green Purchase Decisions? Insights from a Systematic Review. IJERPH 2020, 17, 6607.

- Deliana, Y.; Rum, I.A. How Does Perception on Green Environment across Generations Affect Consumer Behaviour? A Neural Network Process. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 358–367.

- Testa, F.; Pretner, G.; Iovino, R.; Bianchi, G.; Tessitore, S.; Iraldo, F. Drivers to Green Consumption: A Systematic Review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 4826–4880.

- Gleim, M.J.; Lawson, S. Spanning the Gap: An Examination of the Factors Leading to the Green Gap. J. Consum. Mark. 2014, 31, 503–514.

- Cheng, Z.-H.; Chang, C.-T.; Lee, Y.-K. Linking Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Values to Consumer Skepticism and Green Consumption: The Roles of Environmental Involvement and Locus of Control. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 61–85.

More

Information

Subjects:

Business

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Entry Collection:

Environmental Sciences

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Jul 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No