Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Naomi Monsalves | -- | 1232 | 2022-07-20 17:19:25 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | Meta information modification | 1232 | 2022-07-21 03:05:56 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Monsalves, N.; Leiva, A.M.; Gómez, G.; Vidal, G. Antibiotic Resistance in Sewage Treated by Constructed Wetlands. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25355 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Monsalves N, Leiva AM, Gómez G, Vidal G. Antibiotic Resistance in Sewage Treated by Constructed Wetlands. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25355. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Monsalves, Naomi, Ana María Leiva, Gloria Gómez, Gladys Vidal. "Antibiotic Resistance in Sewage Treated by Constructed Wetlands" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25355 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Monsalves, N., Leiva, A.M., Gómez, G., & Vidal, G. (2022, July 20). Antibiotic Resistance in Sewage Treated by Constructed Wetlands. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25355

Monsalves, Naomi, et al. "Antibiotic Resistance in Sewage Treated by Constructed Wetlands." Encyclopedia. Web. 20 July, 2022.

Copy Citation

The emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and their dissemination into the environment through antibiotic-resistant genes (ARGs) have been recognized as one of the main concerns of the 21st century. Constructed wetlands (CWs) are nonconventional treatment technologies that mimic the removal processes of natural wetlands, optimizing operational and design parameters to enhance the removal of contaminants. Understanding the behavior of ARGs and ARB under different conditions will allow CWs to be optimized, avoiding an increase in ARG abundances in the final effluents.

antibiotic-resistant genes

sewage

constructed wetlands

1. Antibiotic-Resistant Genes

Antibiotic-resistant genes (ARGs) are units of nucleic acid information that encode proteins involved in different resistance mechanisms, such as antibiotic inactivation, target site modifications, and reduced antibiotic penetration. In the case of ARGs that are related to the tetracycline family resistance (tetO, tetB, and tetM), these elements encode proteins, which prevent the antibiotic from binding to the ribosome, inhibiting the antibiotic action [1][2]. This AR is a natural phenomenon used by bacteria that gives them adaptive advantages for obtaining resources in the environment compared to other competing species [3][4]. The presence of antibiotics in the environment generates a selective pressure that inhibits the growth of susceptible bacteria, favoring intrinsically resistant bacteria or those that have acquired this resistance over time [1].

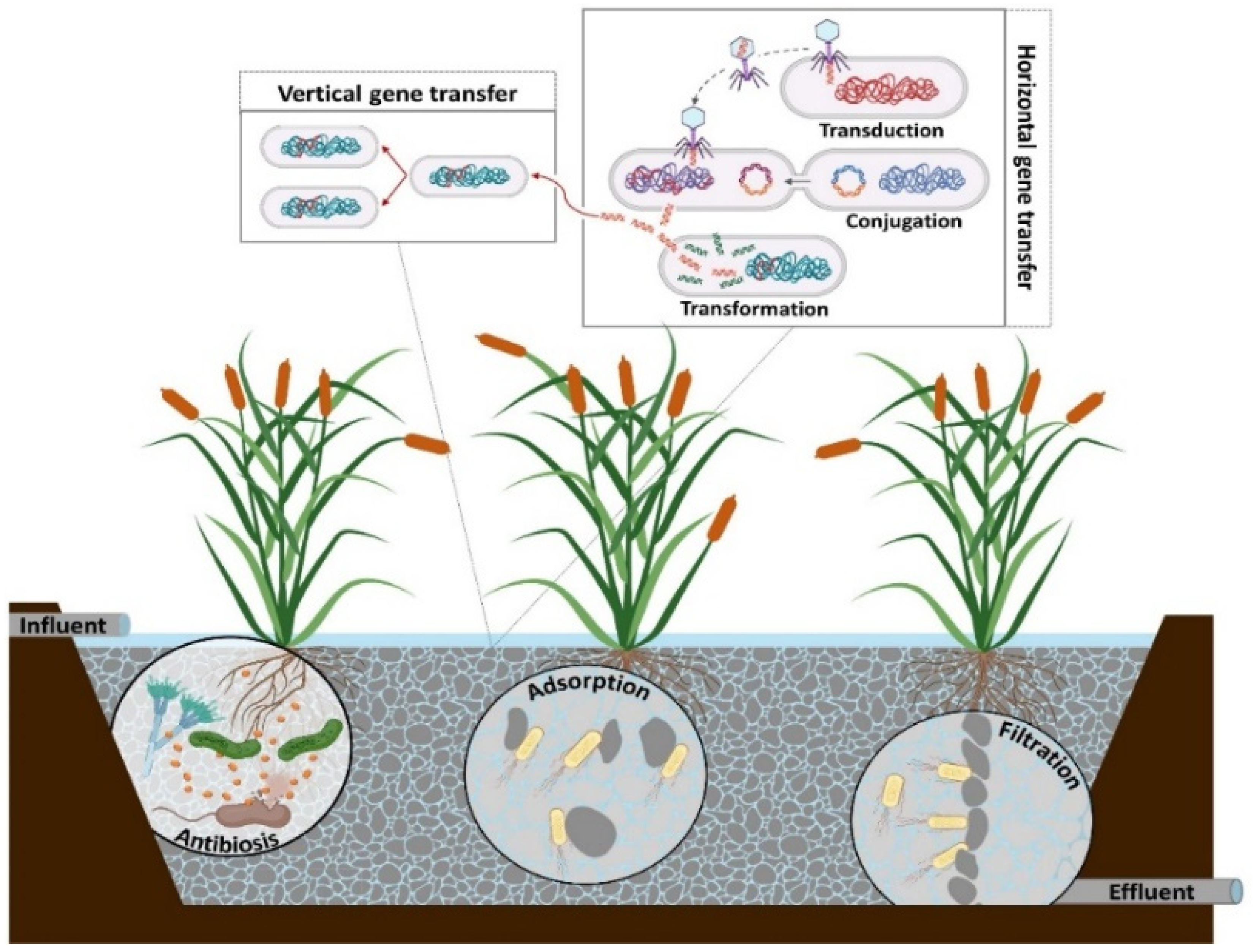

Resistance acquired by bacteria can occur through the transfer of genetic material from other bacteria (of the same or a different species) or point mutations [5]. Figure 1 shows the different processes through which bacteria acquire ARGs. In this case, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) occurs through three genetic mechanisms: 1. Transformation, wherein an extracellular naked ARG is taken up by bacteria that have developed genetic competence; 2. Conjugation, wherein the genetic transfer from antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) to recipient cell occurs through cell-to-cell contact; and 3. Transduction, the mechanism through which an ARG is introduced into a cell by a virus or bacteriophage [5][6]. Vertical gene transfer is another process of AR acquisition that consists of the transfer of genetic material from parents to offspring by ARB after acquiring an AGR through one of the mechanisms mentioned above. This process allows the resistant bacteria rate in the environment to increase [5].

Figure 1. Processes of antibiotic-resistant gene transfer and mechanisms of antibiotic-resistant gene reduction in constructed wetlands. Note: Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 1 April 2022).

As seen in Figure 1, the gene transfer mechanisms mentioned above occur simultaneously within a constructed wetlands (CW) system [7], showing that operational and design conditions are important for reducing ARGs. Therefore, understanding the behavior of ARGs and ARB under different conditions will allow CWs to be optimized, avoiding an increase in ARG abundances in the final effluents.

2. Mechanisms of Antibiotic-Resistant Gene Reduction in Constructed Wetlands

As mentioned above, the effectiveness of ARG reduction in CWs depends on the involved conditions and mechanisms. Different studies have shown a positive correlation between the absolute abundance of ARGs and the rRNA 16S gene, a microbial marker [7][8]. This information could indicate that ARGs are transported by fecal microorganisms in sewage and that the reduction of these microorganisms is related to ARG reductions in the effluents [7][8][9]. The principal mechanisms of ARG reduction in CWs are shown in Figure 1. The antibiosis mechanism is related to the production of low molecular weight antibiotics by a group of bacteria or fungi. They can inhibit the growth of ARB in CWs and therefore decrease ARG abundance [10]. Similarly, it has been reported that plant roots are capable of releasing antibiotic compounds. Shirdashtzadeh et al. [11] and Chandrasena et al. [12] found an efficient inhibition of E. coli growth due to antibiotic release by the plant Malaleuca ericifolia. Likewise, Li et al. [13] reported that extracts from macrophytes, such as Phragmites communis, Typha latifolia, Arundo donax, Polygonum hydropiper, and Polygonum orientale, achieved reductions close to 100% for coliphages T4 and f2.

Other mechanisms of ARB and ARG reduction in CWs are associated with physical processes, such as filtration and adsorption. In both mechanisms, the support medium and rooting capacity of macrophytes play a fundamental role [7][14]. Liu et al. [15] reported reductions of 50% for the tet gene, while Dires et al. [16] achieved an ARB reduction of 77.5%. Both studies suggested that the principal mechanism responsible for achieving these reductions was filtration by zeolite and gravel, respectively. In the case of adsorption, this mechanism is related to the interactions between the contaminants and the support medium or plant roots due to the sorption properties and ionic composition of the medium [17]. Du et al. [8] studied ARG reduction in CWs that used zeolite as a support medium. They determined values of 95.3% for the sul and tet genes. These results can be explained by the porous morphology and larger surface area of zeolite.

3. Antibiotic-Resistant Gene Reductions in Constructed Wetlands

Different types of ARGs can be detected in sewage [9][18][19]. Table 1 shows the absolute abundances and reductions of different ARGs in CWs treating sewage. For rural 0’and urban areas, these values in the influents fluctuated between 1.43 × 106–1.25 × 108 copies/mL and 1.05 × 104–1.58 × 108 copies/mL, respectively. In both types of sewage, the average abundances of ARGs are in the order of 107 copies/mL. However, rural areas are characterized by low populations and scattered households, such that the discharge of untreated sewage into the environment is common, especially in underdeveloped countries [20]. This situation poses a significant risk for antibiotic dissemination into the environment.

Table 1. Absolute abundances and reductions of different antibiotic-resistant genes in constructed wetlands treating sewage.

| Sewage | Flow Configuration |

Macrophyte Type |

Support Medium | HRT | ARGs | Absolute Abundance (Copies/mL) | Reduction (Ulog) | Range | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influent (×106) | Effluent (×106) | |||||||||

| Urban | HSSF, VSSF, SF, VSSF–HSSF | P. australis, T. angustifolia, T. dealbata, C. alterfolius, I. tectorum | tuff, gravel, sand, zeolite | 0.18–6 | sul1 | 8.18 | 7.10 | 0.33 | −0.49–1.01 | [18][21][22][23][24][25][26] |

| sul2 | 8.95 | 7.48 | 0.35 | 0.04–0.9 | ||||||

| sul3 | 6.92 | 6.04 | 0.13 | −0.27–0.75 | ||||||

| ermB | 4.25 | 1.56 | 0.21 | 0.08–0.82 | ||||||

| ermC | 4.43 | 1.62 | 0.42 | 0.30–0.67 | ||||||

| tetM | 0.91 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.34–0.63 | ||||||

| tetO | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.34 | 0.32–0.90 | ||||||

| tetX | 0.04 | 0.005 | 0.60 | 0.31–0.69 | ||||||

| floR | 0.00007 | 0.00004 | 0.75 | −0.02–0.88 | ||||||

| cmlA | 2.64 | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.29–0.74 | ||||||

| Rural | SF–VSSF, SF | P. australis, T. dealbata, T. orientalis, P. cordata, M. vercillatum, I. tectorum | chaff, soil | 0.25–1.5 | sul1 | 1.14 | 0.05 | 0.70 | 0.42–1.55 | [27][28] |

| sul2 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.65 | 0.41–1.34 | ||||||

| sul3 | 1.47 | 0.003 | 0.78 | 0.22–0.78 | ||||||

| tetM | 1.02 | 0.01 | 0.66 | 0.30–2.69 | ||||||

| tetO | 0.42 | 0.002 | 0.73 | 0.51–1.69 | ||||||

| ermB | 0.83 | 0.007 | 2.03 | 0.12–2.03 | ||||||

| ermC | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.14–0.27 | ||||||

Note: HSSF: horizontal subsurface flow; VSSF: vertical subsurface flow; SF: surface flow; VSSF–HSSF: hybrid vertical subsurface flow–horizontal subsurface flow; SF–VSSF: hybrid superficial flow–vertical subsurface flow; P. australis: Phragmites australis; T. angustifolia: Typha angustifolia; T. dealbata: Thalia dealbata; C. alterfolius: Cyperus alterfolius; I. tectorum: Iris tectorum; HRT: hydraulic retention time; ARGs: antibiotic-resistant genes.

The occurrence of ARGs in influent with an average abundance of 2.0 × 107 copies/mL shows the risks associated with the occurrence of HTG and ARB proliferation. These processes can trigger the dissemination of AR into the environment [7][21]. Moreover, concentrations of antibiotics, pesticides, disinfectants, and heavy metals in sewage can increase this risk [5][26].

In addition, Table 1 shows the operating and design parameters of the CWs used by the evaluated studies to reduce ARG abundances in sewage. These parameters include conventional flow configurations, such as SF, HSSF, VSSF, and also hybrid configurations. The type of macrophytes used, support medium, and hydraulic retention time (HRT) can also be visualized.

Regarding the performance of CWs at reducing ARG abundances in sewage, the ARG reductions were above 0.3 ulog except for ermB and tetM. However, these systems achieved variable reductions that can be observed in the wide ranges reported. These ranges fluctuated from negative values (−0.49 to −0.02 ulog) to values above the average of 0.3 ulog. For urban sewage, negative reductions were reported for sul1, sul2, and sul3, with values of −0.49, −0.27, and −0.02 ulog, respectively. These negative reductions indicate an increase in ARG abundance in the effluent. This behavior can be related to the presence of antibiotic and coselective agents in CWs. In the case of rural sewage, higher reductions were reported for tetM and ermB, with values of 2.69 and 2.03 ulog, respectively. Regarding the wide ranges of reductions reported (−0.49 to 2.69 ulog), this result indicates that the ARG reductions in CWs depend on operational and design parameters.

References

- De Oliveira, D.; Forde, B.; Kidd, T.; Harris, P.; Schembri, M.; Beatson, S.; Paterson, D.; Walker, M. Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00181-19.

- Peng, S.; Li, H.; Song, D.; Lin, X.; Wang, Y. Influence of zeolite and superphosphate as additives on antibiotic resistance genes and bacterial communities during factory-scale chicken manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 263, 393–401.

- Alonso, A.; Sánchez, P.; Martinez, J. Environmental selection of antibiotic resistance genes. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 3, 1–9.

- Martínez, J.; Coque, T.; Baquero, F. What is a resistance gene? Ranking risk in resistomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 13, 116–123.

- Amarasiri, M.; Sano, D.; Suzuki, S. Understanding human health risks caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARG) in water environments: Current knowledge and questions to be answered. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 50, 2016–2059.

- Jiang, Q.; Feng, M.; Ye, C.; Yu, X. Effects and relevant mechanisms of non-antibiotic factors on the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in water environments: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150568.

- García, J.; García-Galán, M.J.; Day, J.W.; Boopathy, R.; White, J.R.; Wallace, S.; Hunter, R.G. A review of emerging organic contaminants (EOCs), antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB), and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in the environment: Increasing removal with wetlands and reducing environmental impacts. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 307, 123228.

- Du, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, Q. Removal performance of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in swine wastewater by integrated vertical-flow constructed wetlands with zeolite substrate. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 721, 137765.

- Liu, X.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Lu, S.; Qin, P.; Guo, X.; Bi, B.; Wang, L.; Xi, B.; Wu, F.; et al. Occurrence and fate of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in typical urban water of Beijing, China. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 246, 163–173.

- López, D.; Leiva, A.; Arismendi, W.; Vidal, G. Influence of design and operational parameters on the pathogens reduction in constructed wetland under the climate change scenario. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 18, 101–125.

- Shirdashtzadeh, M.; Chandrasena, G.; Henry, R.; McCarthy, D. Plants that can kill; improving E. coli removal in stormwater treatment systems using Australian plants with antibacterial activity. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 107, 120–125.

- Chandrasena, G.I.; Shirdashtzadeh, M.; Li, Y.L.; Deletic, A.; Hathaway, J.M.; McCarthy, D.T. Retention and survival of E. coli in stormwater biofilters: Role of vegetation, rhizosphere microorganisms and antimicrobial filter media. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 102, 166–177.

- Li, F.; Shi, M.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, N.; Zheng, H.; Gao, C. A novel method of rural sewage disinfection via root extracts of hydrophytes. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 64, 344–349.

- Leiva, A.M.; Piña, B.; Vidal, G. Antibiotic resistance dissemination in wastewater treatment plants: A challenge for the reuse of treated wastewater in agriculture. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 20, 1043–1072.

- Liu, L.; Liu, C.; Zheng, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, G. Elimination of veterinary antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes from swine wastewater in the vertical flow constructed wetlands. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 1088–1093.

- Dires, S.; Birhanu, T.; Ambelu, A.; Sahilu, G. Antibiotic resistant bacteria removal of subsurface flow constructed wetlands from hospital wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4265–4272.

- Wu, S.; Carvalho, P.N.; Müller, J.A.; Manoj, V.R.; Dong, R. Sanitation in constructed wetlands: A review on the removal of human pathogens and fecal indicators. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 541, 8–22.

- Ávila, C.; García-Galán, M.J.; Borrego, C.M.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S.; García, J.; Barceló, D. New insights on the combined removal of antibiotics and ARGs in urban wastewater through the use of two configurations of vertical subsurface flow constructed wetlands. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142554.

- Cacace, D.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Manaia, C.M.; Cytryn, E.; Kreuzinger, N.; Rizzo, L.; Karaolia, P.; Schwartz, T.; Alexander, J.; Merlin, C.; et al. Antibiotic resistance genes in treated wastewater and in the receiving water bodies: A pan-European survey of urban settings. Water Res. 2019, 162, 320–330.

- Huang, Y.; Wu, L.; Li, P.; Li, N.; He, Y. What’s the cost-effective pattern for rural wastewater treatment? J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114226.

- Sabri, N.; Schmitt, H.; van der Zaan, B.; Gerritsen, H.; Rijnaarts, H.; Langenhoff, A. Performance of full scale constructed wetlands in removing antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147–368.

- Chen, J.; Wei, X.D.; Liu, Y.S.; Ying, G.G.; Liu, S.S.; He, L.Y.; Su, H.C.; Hu, L.X.; Chen, F.R.; Yang, Y.Q. Removal of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes from domestic sewage by constructed wetlands: Optimization of wetland substrates and hydraulic loading. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 565, 240–248.

- Chen, Z.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, B.; Li, H.; Chen, Z. Effects of root organic exudates on rhizosphere microbes and nutrient removal in the constructed wetlands. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 92, 243–250.

- Chen, J.; Deng, W.J.; Liu, Y.S.; Hu, L.X.; He, L.Y.; Zhao, J.L.; Wang, T.T.; Ying, G.G. Fate and removal of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in hybrid constructed wetlands. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 894–903.

- Abou-Kandil, A.; Shibli, A.; Azaizeh, H.; Wolff, D.; Wick, A.; Jadoun, J. Fate and removal of bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes in horizontal subsurface constructed wetlands: Effect of mixed vegetation and substrate type. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 59, 144193.

- He, Y.; Nurul, S.; Schmitt, H.; Sutton, N.B.; Murk, T.A.; Blokland, M.H.; Rijnaarts, H.H.; Langenhoff, A.A. Evaluation of attenuation of pharmaceuticals, toxic potency, and antibiotic resistance genes in constructed wetlands treating wastewater effluents. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631–632, 1572–1581.

- Fang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Nie, X.; Chen, B.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Liang, X. Ocurrence and elimination of antibiotic resistance genes in a long-term operation integrated surface flow constructed wetland. Chemosphere 2017, 173, 99–106.

- Chen, J.; Liu, Y.-S.; Su, H.-C.; Ying, G.-G.; Liu, F.; Liu, S.-S.; He, L.-Y.; Chen, Z.-F.; Yang, Y.-Q.; Chen, F.R. Removal of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in rural wastewater by an integrated constructed wetland. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 22, 1794–1803.

More

Information

Subjects:

Environmental Sciences

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.3K

Entry Collection:

Wastewater Treatment

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

21 Jul 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No